Abstract

Recent studies suggest a role for autocrine insulin signaling in beta cells, but the mechanism and function of insulin-stimulated Ca2+ signals is uncharacterized. We examined Ca2+-dependent insulin signaling in human beta cells. Two hundred nanomolar insulin elevated [Ca2+]c to 284 ± 27 nM above baseline in ≈30% of Fura-4F-loaded cells. Insulin evoked multiple Ca2+ signal waveforms, 60% of which included oscillations. Although the amplitude of Ca2+ signals was dose-dependent between 0.002 and 2,000 nM, the percentage of cells responding was highest at 0.2 nM insulin, suggesting the interaction of stimulatory and inhibitory pathways. Ca2+-free solutions did not affect the initiation of insulin-stimulated Ca2+ signals, but abolished the second phase of plateaus/oscillations. Likewise, inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3) receptor antagonists xestospongin C and caffeine selectively blocked the second phase, but not the initiation of insulin signaling. Thapsigargin and 2,5-di-tert-butylhydroquinone (BHQ) blocked insulin signaling, implicating sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA)-containing Ca2+ stores. Insulin-stimulated Ca2+ signals were insensitive to ryanodine. Injection of the CD38-derived Ca2+ mobilizing metabolite, nicotinic acid-adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NAADP), at nanomolar concentrations, evoked oscillatory Ca2+ signals that could be initiated in the presence of ryanodine, xestospongin C, and Ca2+-free solutions. Desensitizing concentrations of NAADP abolished insulin-stimulated Ca2+ signals. Insulin-stimulated Ca2+ signals led to a Ca2+-dependent increase in cellular insulin contents, but not secretion. These data reveal the complexity of insulin signal transduction and function in human beta cells and demonstrate functional NAADP-sensitive Ca2+ stores in a human primary cultured cell type.

Keywords: calcium signals, ryanodine, autocrine, CD38, diabetes mellitus

Discovery of insulin receptors on pancreatic beta cells and the characterization of beta cell-specific insulin receptor null mice with a diabetes-like phenotype suggest a physiological role for autocrine insulin signaling (1). Although results from in vivo and whole islet experiments suggested a negligible or inhibitory effect of insulin on insulin release, recent experiments with dispersed rodent beta cells suggested a stimulatory effect on calcium signaling, insulin expression, and exocytosis (2–7). Unlike glucose signaling, insulin-evoked Ca2+ signals in mouse beta cells required intracellular Ca2+ stores sensitive to the sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA) inhibitor thapsigargin (4). Insulin action was not blocked by a phospholipase C inhibitor, suggesting indirectly that inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3)-sensitive Ca2+ stores were not involved (5). The mechanisms of autocrine insulin feedback are unknown in human beta cells.

Ca2+ signals control multiple functions in secretory cells, and at least three distinct biochemical classes of Ca2+ stores coexist (8, 9). Aside from the phospholipase C/IP3 pathway that is commonly activated by G-protein-coupled receptors, Ca2+ can be mobilized through ryanodine receptors, activated by Ca2+ or cyclic ADP-ribose (cADPr). A third class of Ca2+ store, mobilized by nicotinic acid adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NAADP), functions in oocytes, Jurkat T lymphocytes, and mouse pancreatic acini (8, 10, 11). The production of NAADP and cADPr are catalyzed by CD38 and related ADP-ribosyl cyclases (12, 13). CD38 is found in many cell types, including human beta cells. Glucose-stimulated Ca2+ mobilization and insulin release (in vivo and in vitro) were enhanced by CD38 overexpression and reduced by CD38 knockout (14, 15). Beta cells with poor glucose-stimulated insulin production/release (ob/ob, GK, RINm5F) have less CD38 (16, 17). CD38 autoantibodies, found in ≈14% of diabetic patients, evoked Ca2+ signals and insulin release from human islet cells (18).

In this study, we tested the hypothesis that NAADP-sensitive Ca2+ stores regulate beta cell function, in the context of autocrine insulin signaling. We report that insulin generates complex Ca2+ signals by mobilizing novel intracellular Ca2+ stores in primary cultures of dispersed human islet cells. NAADP-sensitive Ca2+ stores initiate insulin signaling, whereas subsequent oscillatory behavior is sensitive to the removal of extracellular Ca2+ and to putative IP3 receptor inhibitors. These prolonged insulin-stimulated Ca2+ signals regulate cellular insulin levels, but do not measurably stimulate overall secretion.

Materials and Methods

Drugs and Solutions.

Reagents were from Sigma unless otherwise stated. Stocks (<1,000-fold) of BHQ (2,5-di-tert-butylhydroquinone), CPA (cyclopiazonic acid), xestospongin C, BAPTA-AM (1,2-bis-(o-aminophenoxy)ethane-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid acetoxymethyl ester; Calbiochem), and ryanodine were dissolved in DMSO. Thapsigargin stock was dissolved in EtOH. Recombinant insulin, caffeine, IP3, NADP, and NAADP were dissolved directly into solutions. Ca2+ imaging was performed in Ringer's solution containing (in mM): 5.5 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 20 Hepes, 141 NaCl, and 3 glucose. High glucose solutions, KCl and Ca2+-free solutions were made by equimolar substitution of NaCl.

Tissue Culture.

Human islets were provided by the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation Islet Isolation Core (Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis). Islets were gently dispersed after three 1-min washes with Ca2+/Mg2+-free Eagle's minimal essential media (MEM; Mediatech, Herndon, VA), followed by 30-s exposure to trypsin/EDTA (GIBCO) solution diluted 1:5 in MEM. Cells were plated on coverslips in RPMI 1640 [containing 5.5 mM glucose and 100 units/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin (pH 7.4) with NaOH] and supplemented with 10% FCS. Cultures were maintained at 37°C, 5% CO2 and saturated humidity. Cells were studied 2–4 days after dispersion. Experiments were replicated on cells from two to five donors.

Ca2+ Imaging.

Islet cells were incubated with 1 μM Fura-4F-AM (Molecular Probes) in RPMI 1640 for 30 min and rinsed in Ringer's solution for 30 min. Coverslips, in a narrow 32°C chamber, were continuously perifused with preheated solutions to maximize control over the contents of the bath. Recordings were made from 6–25 cells by using a monochromator, a charge-coupled device (CCD) camera (TILL Photonics, Planegg, Germany) and an IX70 microscope (×20 or ×40 objectives; Olympus, Tokyo). Ratios (340/380) were calibrated by exposing cells to 10 μM ionomycin for >30 min (RMAX), then 20 μM EGTA (RMIN). Ca2+ responses were defined as having 1-min bins with a mean [Ca2+]c that was more than two standard deviations over the mean [Ca2+]c of the 5-min pretreatment period. Ca2+ responses listed in the text were quantified as maximal amplitude above baseline. Unless indicated otherwise, the number of replicates reported in the figure legends and text represents the total number of islet cells in imaging experiments.

Microinjection.

Fura-4F-AM-loaded islet cells were injected by using an Eppendorf 5126. Microinjection pressure was 100 hPa (60 hPa compensation, duration 0.5 s). Either Eppendorf Femtotips II or pipettes pulled in house were filled with filtered “intracellular solution” consisting of (in mM): 144 KCl, 2 MgCl2, 2 Na2ATP, 5 EGTA, and 20 Hepes (pH 7.3 with KOH). No differences in the responses were seen when water was used as a vehicle. Unsuccessful injections (≈15%) showed immediate cell swelling and decrease in fluorescence and were discarded.

Hormone Release and RIA.

Dispersed cells were cultured for 3 days on NUNCLON culture plates (Nalge). Cells were washed for 30 min, then incubated as above for 90 min in Kreb's Ringer's buffer containing (in mM): 115 NaCl, 24 NaHCO2, 5 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, and 5 g/liter RIA grade albumin, after which the supernatant was removed and frozen for subsequent RIA. BAPTA-AM was included in the 30-min wash for some experiments. Cellular hormone content was measured after lysing cells by freeze/thaw cycles and sonication in distilled H2O containing 10 micro-trypsin inhibitory units (μTIU)/ml aprotinin (Sigma). Human insulin and c-peptide radioimmunoassays were conducted by the Washington University School of Medicine RIA facility.

Statistical Analysis.

The effects of treatments on the frequency of responses to insulin were evaluated by χ2 test. Statistical analyses on parametric data were performed by using Student's unpaired t test or one-way ANOVA [followed by Fisher's probable least-squares difference (PLSD) post hoc test]. Differences were considered significant when P < 0.05. Results are presented as mean ± SEM.

Results and Discussion

Human Beta Cells Generate Complex Insulin-Evoked Ca2+ Signals.

We imaged a large number of cells (n = 335) to establish the occurrence, and characterize the extended time course, of insulin-stimulated Ca2+ signals in human pancreatic islet cells. On treatment with 200 nM insulin for 15 min, 31% of cells responded with significant Ca2+ signals (mean amplitude 284 ± 24 nM above baseline). The fraction of human islet cells responding to 200 nM insulin is comparable to previous findings in mouse islet cultures; there, 43% of tolbutamide-sensitive cells responded to a 30-s pulse of 100 nM insulin (4, 5).

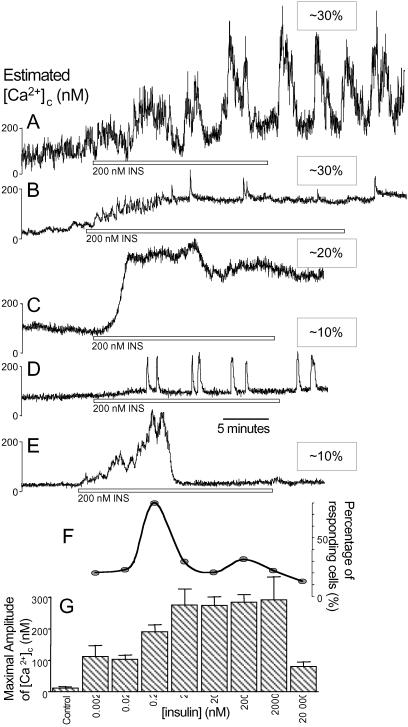

Multiple Ca2+ signal waveforms were observed (Fig. 1 A–E). The first type was characterized by two or more large bursts superimposed on a prolonged plateau. The second type of Ca2+ signal consisted of higher-frequency oscillations on a sustained plateau. A third type consisted of a large monophasic response without oscillations. Less common was a fourth type of response that included short spikes with a negligible plateau phase, and a fifth type exhibiting a single transient burst that returned to the preexposure baseline. Thus, salient features of insulin-stimulated Ca2+ signals are oscillatory behavior (70%) and a plateau that persists during wash out (≈80%). The significance and mechanism of these oscillations is not clear. Surprisingly, removal of insulin evoked a large transient Ca2+ signal in ≈15% of nonresponding cells (not shown). Perhaps cells responded to low insulin levels during the process of wash out.

Fig 1.

Insulin-stimulated Ca2+ signals in human islet cells. (A–E) Representative traces from 101 of 335 cells responding to 200 nM insulin (INS, open bars) are shown. The relative frequency of each wave form, of the 30% of insulin-responsive cells, is indicated. (F) The percentage of cells responding at each insulin concentration (0.002–20,000 nM). (G) The maximal amplitude of Ca2+ signals for various insulin levels (n = 23, 18, 335, 29, 20, 85, 35, and 25; increasing [insulin]) compared with control solution changes (n = 10).

Next, we examined the dose-response relationship of autocrine insulin signaling. The maximal amplitude of the Ca2+ signals above baseline increased from picomolar concentrations of insulin to maximal levels at 2–2,000 nM insulin, but were reduced at 20,000 nM (Fig. 1G). Interestingly, the percentage of islet cells responding did not follow a similar pattern. This dose-response profile had a minor peak at 200 nM insulin and a major peak at 0.2 nM insulin, where 80% of cells responded (Fig. 1F). Ca2+ signals in 0.2 nM insulin were generally smaller and monophasic. This complex concentration-response profile can be explained by an interaction between positive and negative regulators of beta cell [Ca2+]c with distinct concentration dependencies. Indeed, insulin (1–600 nM) reduced beta cell electrical activity dose-dependently by activating KATP channels in a mouse beta cells and islets bathed in high glucose (19). Alternatively, the smaller Ca2+ signals seen at 20,000 nM could be caused by the buildup of a second messenger that has strong desensitizing properties.

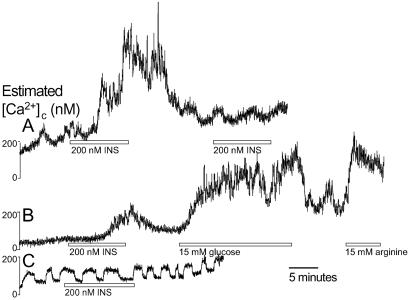

Other features of insulin-induced Ca2+ signals are presented in Fig. 2. First, successive exposures to insulin did not evoke repeated Ca2+ signals (Fig. 2A), suggesting the involvement of a depletable or desensitizable component. Second, we wanted to be reasonably certain that beta cells respond to insulin (60–80% of islet cells contain insulin). Indeed, insulin-stimulated Ca2+ signals occurred predominantly in larger cells, which have been shown to correspond to beta cells in many studies. In addition, where insulin-stimulated Ca2+ signals were relatively modest, 15 mM glucose and 15 mM arginine evoked subsequent Ca2+ signals (Fig. 2B), demonstrating that insulin stimulates beta cells. However, when insulin-stimulated Ca2+ signals were large and prolonged, additional increases in [Ca2+]c were not evoked by 15 mM glucose (n = 25, not shown). Insulin did not increase [Ca2+]c in small cells exhibiting oscillations in 3 mM glucose indicative of alpha cells or delta cells (n = 7; ref 20; Fig. 2C). In previous studies, mouse islet cells were treated with tolbutamide to identify putative beta cells (ref. 4, but see ref. 21). We avoided this approach because such stimulation alters beta cell Ca2+ homeostasis and bath insulin levels.

Fig 2.

Islet cells with the physiological characteristics of beta cells, but not alpha or delta cells, respond to single insulin treatments. (A) Repeated insulin treatments did not reliably evoke multiple Ca2+ signals (n = 21). (B) Insulin-stimulated Ca2+ signals could be localized to beta cells sensitive to sequential application of 15 mM glucose and 15 mM arginine (n = 41). (C) Cells displaying obvious alpha cell or delta cell behavior did not respond to insulin (n = 7).

Novel Intracellular Ca2+ Stores Mediate Insulin Signaling.

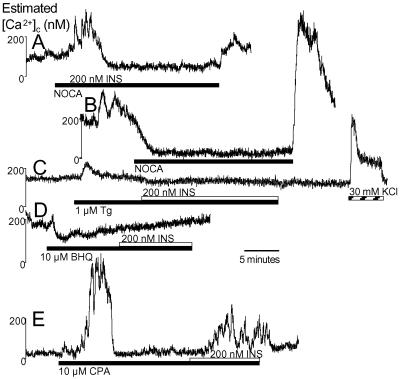

To determine the mechanism of insulin-stimulated Ca2+ signals, we used inhibitors of various different Ca2+ signaling pathways. Response rates and amplitudes in the presence of both insulin and inhibitors were compared with the responses of cells treated with insulin alone (parallel controls) because sequentially repeatable responses were not reliably observed with long insulin treatments. As was the case in cells stimulated with 200 nM insulin under control conditions, 30% of the cells initiated responses in nominally Ca2+-free solution, suggesting that these Ca2+ signals originated from intracellular Ca2+ stores (Fig. 3A; 189 ± 22 nM). However, the absence of plateaus/bursts indicated that the second phase of the insulin-stimulated Ca2+ signals required influx of extracellular Ca2+. Cells with elevated Ca2+ in normal extracellular [Ca2+] (≈200 nM; 20%) showed an immediate reduction in [Ca2+]c on exposure to low Ca2+ Ringers (Fig. 3B), indicating that extracellular Ca2+ influx is constitutively active in a some cells and that changes in extracellular Ca2+ were rapid.

Fig 3.

Insulin-stimulated Ca2+ signals are initiated by intracellular Ca2+ stores. (A) Exposure to Ringer's solution without Ca2+ salts (NOCA) did not inhibit the first phase, but did block the second phase (n = 64). (B) NOCA Ringer's solution reduces [Ca2+]c in some cells with high baseline values. (C and D) Insulin-stimulated Ca2+ signals were abolished in 1 μM thapsigargin (n = 82) (C) or 10 μM BHQ (n = 64) (D). (E) CPA evoked robust Ca2+ signals. Only 15% of all cells responded to insulin in the presence of CPA, representing approximately half the usual number of responsive cells (n = 71).

Next, we directly confirmed the involvement of intracellular Ca2+ stores in insulin signaling by blocking SERCA pumps, which refill many agonist-sensitive Ca2+ stores, with three structurally different inhibitors: thapsigargin, BHQ, and CPA (22). Insulin-stimulated Ca2+ signals were virtually abolished in 1 μM thapsigargin (Fig. 3C; 3% of cells displayed diminutive responses), whereas 30 mM KCl-induced Ca2+ signals were unaffected. No cells responded to insulin in the presence of 10 μM BHQ (Fig. 3D). Surprisingly, exposure to 10 μM CPA alone produced larger elevations in [Ca2+]c when compared with thapsigargin and BHQ, suggesting the possibility of distinct molecular actions (J.D.J., unpublished results). In the presence of CPA, insulin generated normal-sized Ca2+ signals (286 ± 57 nM) in 15% of cells (Fig. 3E), suggesting that a subpopulation of cells requires CPA-sensitive Ca2+ stores for insulin signaling. Thus, insulin releases Ca2+ stores refilled by thapsigargin/BHQ-sensitive SERCA.

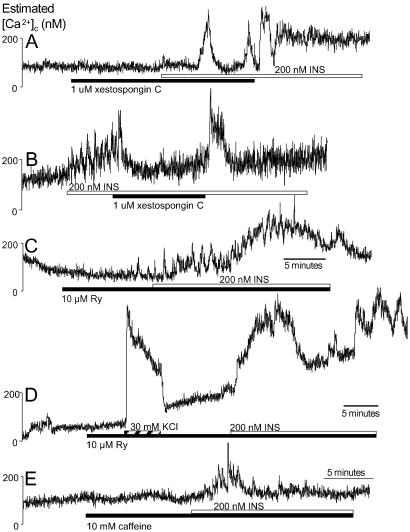

Having established that intracellular Ca2+ stores mediate insulin signaling in human beta cells, we examined which intracellular Ca2+ mobilization pathway(s) are involved. It is established that beta cells contain IP3-sensitive Ca2+ stores, which mediate the signaling of some agonists and play a role in the generation of Ca2+ oscillations (23). In the presence of 1 μM xestospongin C, a putative IP3 receptor inhibitor (ref. 24, see below), the initiation of insulin signaling was still observed (Fig. 4A; 248 ± 27 nM; 40% responded), but the plateau was reversibly inhibited (Fig. 4B).

Fig 4.

Insulin signaling is not initiated by IP3- or ryanodine-sensitive Ca2+ stores. (A) Xestospongin C did not block the first phase of insulin-stimulated Ca2+ signals (n = 20). The second phase was absent or consisted only of baseline spiking. (B) Xestospongin C, applied after the initiation of insulin-stimulated Ca2+ signals, inhibited oscillations (n = 4 insulin-responding cells). (C and D) Neither phase of the Ca2+ signals evoked by insulin is sensitive to 10 μM ryanodine (Ry; n = 52), regardless of preexposure to 30 mM KCl (n = 14). (E) Caffeine did not inhibit the initiation of insulin-stimulated Ca2+ signals (n = 44).

Human beta cells also possess Ca2+ stores mobilized via RyR2 activation (25). Indeed, 1–10 nM ryanodine, which locks RyR in an open subconductance state, evoked Ca2+ signals in beta cells with a maximal amplitude of 117 ± 24 nM, confirming the presence of functional ryanodine-sensitive Ca2+ stores in our preparations (n = 21; not shown). Notwithstanding, 10 μM ryanodine did not block either phase of insulin-stimulated Ca2+ signals (Fig. 4C; 233 ± 30 nM; 35% responded). Ryanodine binds to RyR in their open conformation, making ryanodine action use-dependent in some cells (26). A protocol with a 30 mM KCl pretreatment to activate RyR-mediated Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release still failed to inhibit insulin signaling (Fig. 4D; 285 ± 56 nM; 43% responded). Caffeine, which can empty RyR-containing Ca2+ stores or inhibit IP3R-dependent Ca2+ release depending on the cell type (26), did not affect the initiation of insulin-evoked Ca2+ signals (167 ± 13 nM; 27% responded, Fig. 4E), but inhibited the plateau phase. Caffeine evoked only modest Ca2+ release in 14% of cells. Together, these data strongly suggest that IP3R- and RyR-linked pathways, including those downstream of cyclic ADP-ribose accumulation, do not initiate insulin signaling in human beta cells.

NAADP-Sensitive Ca2+ Stores Mediate Insulin Signaling.

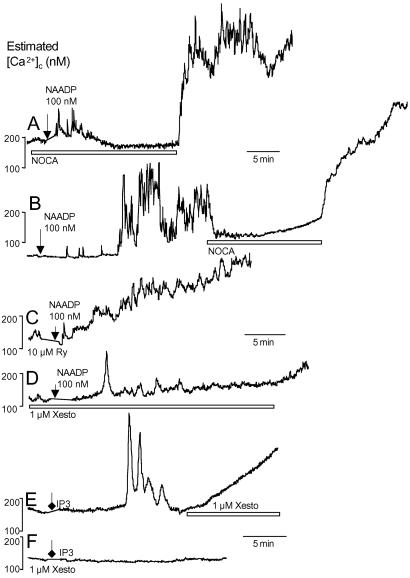

In mammalian cells, NAADP is the most potent intracellular Ca2+-releasing metabolite known (10) and is involved in Jurkat T lymphocyte activation (11) and cholecystokinin (CCK) signaling in pancreatic acinar cells (8). Complex Ca2+ signals were evoked in large cells injected with NAADP (but not β-NADP or buffer), with a concentration-response profile peaking at 100 nM (Fig. 5), similar to what has been previously reported in T cells (11). Injection of NAADP was sufficient to reproduce several characteristics of insulin-evoked Ca2+ signals. As in T lymphocytes (11), bursts occurred at intervals of several minutes. Our findings contrast with the observations of others (27), where permeabilized ob/ob mouse beta cells did not respond to 10 nM–10 μM NAADP. If NAADP-sensitive Ca2+ stores are immediately below the plasma membrane, as they are in some cell types, they may have been destroyed with permeabilization. Using injection, our data strongly suggest that human beta cells possess NAADP-sensitive Ca2+ stores, with properties similar to other cell types.

Fig 5.

Functional NAADP-sensitive Ca2+ stores exist in human beta cells. (A) Large islet cells injected with various concentrations of NAADP exhibited oscillatory [Ca2+]c elevations. (B) Maximal amplitude above baseline of Ca2+ signals evoked in individual cells injected with 10 different pipet concentrations of NAADP (n = 6, 3, 8, 16, 12, 5, 4, 2, 4, and 3; increasing [NAADP]). (C) β-NADP (10 μM) did not evoke Ca2+ signals (n = 8).

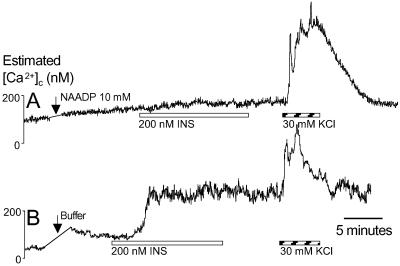

We further tested the involvement of NAADP-sensitive Ca2+ stores in insulin signaling by desensitizing the NAADP receptor with micromolar concentrations of NAADP (8, 10, 11). Injection of 10 mM NAADP blocked all insulin-stimulated Ca2+ signals (Fig. 6A). Cells injected with buffer alone responded to insulin (Fig. 6B; 181 ± 39 nM; 24% responded). Subsequent depolarization-evoked Ca2+ influx was not affected by the injection procedure, indicating that general Ca2+ homeostasis remained intact. Taken together, these data demonstrate that, in human beta cells, NAADP-sensitive Ca2+ stores are required to initiate insulin signaling. These findings complement other work supporting a role for CD38 in beta cell physiology (14, 15, 18). However, previous studies have focused on cADPr as the mediator of CD38 signaling. Although a rise in cADPr is coincidental with glucose stimulation, evidence suggests that cADPr is not sufficient for insulin release and that glucose-stimulated insulin release is not blocked by a cADPr inhibitor (28). Our data suggest that the cADPr/RyR pathway is not involved in autocrine insulin signaling in beta cells.

Fig 6.

NAADP-sensitive Ca2+ stores mediate insulin signaling. (A) Injection of 10 mM NAADP to desensitize the NAADP-receptor blocked all insulin-stimulated Ca2+ signals (n = 28). (B) Insulin evoked normal Ca2+ signals after injection with buffer (n = 24).

CD38 is found on the plasma membrane and in multiple organelles, including the nucleus (29–31). CD38 is known to favor the production of NAADP over cADPr at acidic pHs or in the presence of cAMP and may require endocytosis, suggesting its subcellular location may be important (32, 33). The exact cellular location of NAADP-sensitive Ca2+ stores is also unknown, but they are pharmacologically distinct from Ca2+ stores sensitive to IP3 or cADPr/ryanodine in other cell types. NAADP initiated Ca2+ signals in human beta cells preincubated for ≈2 min in Ca2+-free solutions, but did not elicit secondary oscillations or plateaus (Fig. 7A). The second phase of NAADP-induced Ca2+ signals was blocked by removing Ca2+ (Fig. 7B). NAADP-stimulated Ca2+ signals were insensitive to RyR blockade. Likewise, Ca2+ release could be initiated by NAADP, but not IP3, in the presence of xestospongin C (Fig. 7 D–F). These results indicate that NAADP acts on Ca2+ stores relatively distinct from those modulated by ryanodine and xestospongin in this cell type with a pharmacological profile similar to that of insulin. Interestingly, NAADP-stimulated Ca2+ release can be inhibited by voltage-gated Ca2+ channel antagonists (34), which are potent suppressors of Ca2+ signaling in human beta cells (35).

Fig 7.

Properties of NAADP-induced Ca2+ signaling. (A) Ca2+ signals could be initiated by 100 nM NAADP in nominally Ca2+-free conditions (NOCA, n = 4). (B) Removal of Ca2+ abrogated a second phase of Ca2+ signaling in cells previously stimulated by NAADP (n = 2). (C) Neither the initiation nor the maintenance of NAADP-evoked Ca2+ signals was sensitive to 10 μM ryanodine (Ry; n = 5). (D) Xestospongin C (Xesto) did not block the initiation if NAADP-stimulated Ca2+ release (n = 3). (E) Microinjection of 100 μM IP3 evoked oscillatory Ca2+ signals (n = 9). Often, 1 μM xestospongin C induced a slow elevation in Ca2+ in cells previously stimulated with IP3 (n = 3). (F) IP3 (100 μM) did not evoke Ca2+ signals in the presence of xestospongin C (n = 5).

We present evidence for the sequential activation of multiple Ca2+ stores in beta cells, as in mouse pancreatic acinar cells where NAADP initiates Ca2+ release upstream of IP3 receptors (8). Future work is required to determine the mechanism by which the insulin receptor substrate-1 (IRS-1)/phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) pathway releases intracellular Ca2+. It is possible that the first and second phase of insulin signaling, or the distinct Ca2+ waveforms, may have different physiological functions. In Ascidian oocytes, both cADPr- and NAADP-sensitive Ca2+ stores modulate membrane currents, but only cADPr regulates exocytosis (36). The subcellular location, amplitude, duration, and oscillation frequency of specific Ca2+ signals can lead to the differential regulation of cellular processes (37–39). Multiple Ca2+ stores, found in several organelles, add further complexity required to control the vast array of Ca2+-dependent cellular functions in endocrine cells (9).

Functional Consequences of Insulin Signaling.

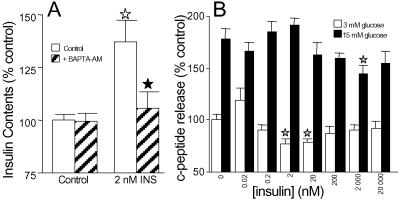

Because a common feature of insulin-stimulated Ca2+ signals was their prolonged duration, we investigated the long-term actions of insulin on dispersed human islet cells by using cellular insulin content as an indicator of insulin production and secreted c-peptide as a marker of insulin exocytosis. We observed a marked increase in cellular insulin accumulation in cells treated with insulin for 90 min that was abolished by preincubating cells in BAPTA-AM, a membrane permeant Ca2+ buffer (Fig. 8A). The elevation in cellular c-peptide/insulin contents by insulin (0.2–200 nM) is time-dependent and reflects newly synthesized insulin (J.D.J., unpublished observations). These results complement previous studies describing a robust effect of insulin on insulin gene expression and protein synthesis (6, 40). Consistent with the role of insulin in insulin production and presence of known antiapoptotic components in the insulin signaling pathway (41, 42), islets of diabetic beta cell-specific insulin receptor knockout mice were 20–40% smaller and contained 35% less insulin (1). Interestingly, insulin activation of the pancreatic transcription factor PDX-1 is independent of KATP channel-mediated membrane excitability (43), suggesting a possible role for intracellular Ca2+ stores. Although both the production and secretion of hormones are dependent on calcium at several levels (9, 35, 44), insulin biosynthesis and secretion are not always coupled (45). In dispersed human islet cells, exogenous insulin did not stimulate c-peptide secretion in either resting or high glucose (Fig. 8B) in 90-min static incubations (or at 5 min, 30 min, or 6 h; J.D.J., unpublished observations). At some concentrations, secretion was significantly inhibited. Notably, high-resolution amperometry studies showed that the application of 100 nM insulin resulted in only modest exocytosis (≈10 insulin granules) in a minority of beta cells (4, 5). That insulin does not stimulate robust, prolonged hormone release agrees with the requirement for voltage-gated Ca2+ channel-mediated Ca2+ influx for exocytosis in human beta cells (35).

Fig 8.

Physiological outcomes of insulin signaling. (A) Insulin increased cellular insulin contents in dispersed islet cells during 90-min static incubations, through mechanisms sensitive to preincubation with 10 μM BAPTA-AM for 30 min (n = 6). Open stars indicate significant stimulation compared with control. Filled stars indicate significant inhibition by BAPTA. (B) Insulin does not stimulate c-peptide release from dispersed islet cells in static incubation (n = 18). Stars indicate significant difference from appropriate control.

In conclusion, we have characterized in beta cells a third class of intracellular Ca2+ store, sensitive to NAADP, which mediates autocrine insulin feedback. These Ca2+ stores comprise an early step in the generation of complex Ca2+ signals that are sustained through the influx of extracellular Ca2+ and xestospongin/caffeine-sensitive processes. These results provide a basis for the comparison of beta cell insulin signaling with insulin signaling in other tissues and with the signal transduction of other growth factors.

Acknowledgments

We thank B. Olack at the Washington University School of Medicine (St. Louis) Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation Islet Isolation Core for the generous gift of islets (T. Mohanakumar, director). We thank K. Hruska (Washington University School of Medicine) for the loan of the microinjection equipment and S. Doran (University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB, Canada) for advice on microinjection technique. We thank W. Pearson (Washington University School of Medicine) for discussions and programming in igor. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant DK37380 (to S.M.). J.D.J. was supported by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (Canada) and the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation.

Abbreviations

SERCA, sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic Ca2+-ATPase

IP3, inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate

cADPr, cyclic ADP-ribose

NAADP, nicotinic acid-adenine dinucleotide phosphate

BHQ, 2,5-di-tert-butylhydroquinone

CPA, cyclopiazonic acid

BAPTA-AM, 1,2-bis-(o-aminophenoxy)ethane-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid acetoxymethyl ester

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

References

- 1.Kulkari R. N., Bruning, J. C., Winnay, J. N., Postic, C., Magnuson, M. A. & Kahn, C. R. (1999) Cell 96, 329-339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Elahi D., Nagulesparan, M., Hershcopf, R. J., Muller, D. C., Tobin, J. D., Blix, P. M., Rubenstein, A. H., Unger, R. H. & Andres, R. (1982) N. Engl. J. Med. 306, 1196-1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stagner J., Samols, E., Polonsky, K. & Pugh, W. (1986) J. Clin. Invest. 78, 1193-1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aspinwall C. A., Lakey, J. R. T. & Kennedy, R. T. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 6360-6365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aspinwall C. A., Qian, W.-J., Roper, M. G., Kulkari, R. N., Kahn, C. R. & Kennedy, R. T. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 22331-22338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leibiger B., Wahlander, K., Berggren, P.-O. & Leibiger, I. B. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 30153-30156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xu G. G., Gao, Z.-y., Borge, P. D., Jegier, P. A., Young, R. A. & Wolf, B. A. (2000) Biochemistry 39, 14912-14919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cancela J. M., Churchill, G. C. & Galione, A. (1999) Nature 398, 74-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnson J. D. & Chang, J. P. (2000) Biochem. Cell. Biol. 78, 217-240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee H. C. (2001) Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 41, 317-345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berg I., Potter, B. V. L., Mayr, G. W. & Guse, A. H. (2000) J. Cell Biol. 150, 581-588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aarhus R., Graeff, R. M., Dickey, D. M., Walseth, T. F. & Lee, H. C. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270, 30327-30333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chini E. N., Chini, C. C. S., Kato, I., Takasawa, S. & Okamoto, H. (2002) Biochem. J. 362, 125-130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kato I., Takasawa, S., Akabane, A., Tanaka, O., Abe, H., Takamura, T., Suzuki, Y., Nata, K., Yonekura, H., Yoshimoto, T., et al. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270, 30045-30050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kato I., Yamamoto, Y., Fujimura, M., Noguchi, N., Takasawa, S. & Okamoto, H. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 1869-1872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Takasawa S., Akiyama, T., Nata, K., Kuroki, M., Tohgo, A., Noguchi, N., Kobayashi, S., Kato, I., Katada, I. & Okamoto, H. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 2497-2500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matsuoka T., Kajimoto, Y., Watada, H., Umayahara, Y., Kubota, M., Kawamori, R., Yamasaki, Y. & Kamada, T. (1995) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 214, 239-246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Antonelli A., Baj, G., Marchetti, P., Fallahi, P., Surico, N., Pupilli, C., Malavasi, F. & Ferrannini, E. (2001) Diabetes 50, 985-991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khan F. A., Goforth, P. B., Zhang, M. & Satin, L. S. (2001) Diabetes 50, 2192-2198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nadal A., Quesada, I. & Soria, B. (1999) J. Physiol. (London) 517, 85-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Göpel S. O., Kanno, T., Barg, S., Weng, X. G., Gromada, J. & Rorsman, P. (2000) J. Physiol. (London) 528, 509-520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pozzan T., Rizzuto, R., Volpe, P. & Meldolesi, J. (1994) Physiol. Rev. 74, 595-636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ammala C., Larsson, O., Berggren, P. O., Bokvist, K., Juntti-Berggren, L., Kindmark, H. & Rorsman, P. (1991) Nature 353, 849-852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gafni J., Munsch, J. A., Lam, T. H., Catlin, M. C., Costa, L. G., Molinski, T. F. & Pessah, I. N. (1997) Neuron 19, 723-733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Islam M. S., Leibiger, I., Leibiger, B., Rossi, D., Sorrentino, V., Ekstrom, T. J., Westerblad, H., Andrade, F. H. & Berggren, P. O. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 6145-6150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ehrlich B. E., Kaftan, E., Bezprozvannaya, S. & Bezprozvanny, I. (1994) Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 15, 145-149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tengholm A., Hellman, B. & Gylfe, E. (2000) Cell Calcium 27, 43-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Webb D. L., Islam, M. S., Efanov, A. M., Brown, G., Kohler, M., Larsson, O. & Berggren, P. O. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 19074-19079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meszaros L. G., Wrenn, R. W. & Varadi, G. (1997) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 234, 252-256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liang M., Chini, E. N., Cheng, J. & Dousa, T. P. (1999) Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 371, 317-325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Adebanjo O. A., Anandatheerthavarada, H. K., Koval, A. P., Moonga, B. S., Biswas, G., Sun, L., Sodam, B. R., Bevis, P. J., Huang, C. L., Epstein, S., et al. (1999) Nat. Cell Biol. 1, 409-414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wilson H. L. & Galione, A. (1998) Biochem. J. 331, 837-843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Funaro A., Reinis, M., Trubiani, O., Santi, S., Di Primio, R. & Malavasi, F. (1998) J. Immunol. 160, 2238-2247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Genazzani A. A., Mezna, M., Dickey, D. M., Michelangeli, F., Walseth, T. F. & Galione, A. (1997) Br. J. Pharmacol. 121, 1489-1495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Misler S., Barnett, D. W., Gillis, K. D. & Pressel, D. M. (1992) Diabetes 41, 1221-1228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Albrieux M., Lee, H. C. & Villaz, M. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 14566-14574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dolmetsch R. E., Lewis, R. S., Goodnow, C. C. & Healy, J. I. (1997) Nature 386, 855-858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dolmetsch R. E., Xu, K. & Lewis, R. S. (1998) Nature 392, 933-936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Berridge M. J. (1997) J. Physiol. (London) 499, 291-306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xu G., Marshall, C. A., Lin, T.-A., Kwon, G., Munivenkatappa, R. B., Hill, J. R., Lawrence, J. C., Jr. & McDaniel, M. L. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 4485-4491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Paraskevas S., Aikin, R., Maysinger, D., Lakey, J. R. T., Cavanagh, T. J., Agapitos, D., Wang, R. & Rosenberg, L. (2001) Ann. Surg. 233, 124-133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yano S., Tokumitsu, H. & Soderling, T. R. (1998) Nature 396, 584-587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wu H., MacFarlane, W. M., Tadayyon, M., Arch, J. R., James, R. F. & Docherty, K. (1999) Biochem. J. 344, 813-818. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Guest P. C., Bailyes, E. M. & Hutton, J. C. (1997) Biochem. J. 323, 445-450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pipeleers D. G., Marical, M. & Malaisse, W. J. (1973) Endocrinology 93, 1001-1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]