Abstract

Spin labels have been extensively used to study the dynamics of oligonucleotides. Spin labels that are more rigidly attached to a base in an oligonucleotide experience much larger changes in their range of motion than those that are loosely tethered. Thus, their electron paramagnetic resonance spectra show larger changes in response to differences in the mobility of the oligonucleotides to which they are attached. An example of this is 5-(2,2,5,5-tetramethyl-3-ethynylpyrrolidine-1-oxyl)-uridine (1). How ever, the synthesis of this modified DNA base is quite involved and, here, we report the synthesis of a new spin-labeled DNA base, 5-(2,2,6,6-tetramethyl-4-ethynylpiperidyl-3-ene-1-oxyl)-uridine (2). This spin label is readily prepared in half the number of steps required for 1, and yet behaves in a spectroscopically analogous manner to 1 in oligonucleotides. Finally, it is shown here that both spin labels 1 and 2 can be used to detect the formation of both double-stranded and triplex DNA.

INTRODUCTION

Spin labels have been used for many years to probe the conformational mobility and other structural properties of oligonucleotides (1–3). Their utility lies in the electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) signal that can be observed and its sensitivity to motion. The EPR spectra of unconstrained spin-labeled oligonucleotides are mainly isotropic. As the spin-labeled oligonucleotide becomes more constrained the corresponding EPR spectrum becomes anisotropic. Thus, by monitoring the EPR spectrum of a spin-labeled oligonucleotide it is possible to observe the formation of a variety of DNA structures such as loops and double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) (4–7). Note that the degree of constraint can be analyzed in quantitative terms by computer simulation of the spectra and extraction of the correlation time for the spin probe (7,8).

The structure of the spin-labeled oligonucleotide significantly affects the extent to which the EPR spectrum changes upon binding. Spin-labeled oligonucleotides that are attached to DNA or RNA bases by a flexible tether (e.g. single bonds) show relatively small differences between single- and double-stranded DNA states (4,5). Similarly, spin labels attached to the backbone of DNA, such as by covalent attachment to a phosphorothioate, also show small but measurable differences between unbound and bound states (9). Spin labels that are more rigidly attached to the oligonucleotide, show large changes in their EPR spectra between the unbound and bound forms, as demonstrated, for example, by Spaltstein et al. (10,11). These latter workers synthesized a spin-labeled thymidine analog phosphoramidite (1) (Fig. 1), and prepared several oligonucleotides containing this spin label. In turn, these oligonucleotides were used to examine the EPR spectra of a variety of DNA structures. These workers obtained a range of correlation times spanning ∼1–20 ns, effectively spreading out the time scale so that it was easier to discern different environments or different DNA structures.

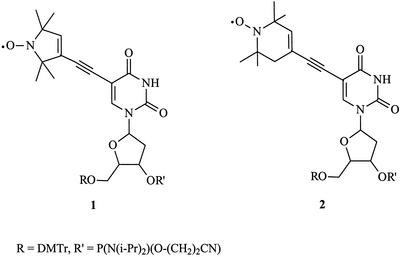

Figure 1.

Structures of the spin-labeled phosphoramidites 1 (5spT15) and 2 (6spT15).

The spin label 1 has been shown to be very useful for detecting and distinguishing between various DNA structures. However, the synthesis of 1 requires 12 steps and similar, but more synthetically accessible, probes would facilitate their use. Therefore, we designed and synthesized a new spin label, 2, and its phosphoramidite, which can be prepared in six steps from readily available starting materials (12). In addition, we have measured the EPR spectra of single-, double-, and triple-stranded oligonucleotides containing either 1 or 2, and show that they are quite similar based on their EPR spectra, thermal denaturation temperatures and circular dichroism (CD) spectra. Finally, we have found that oligonucleotides containing either spin label can be used to detect triplex DNA (txDNA) and may aid in determining txDNA rigidity and stability.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

General

Solvents and reagents were obtained from Aldrich (Milwaukee, WI) and were used without purification unless otherwise noted. NMR spectra were obtained on a Varian Gemini 300 broadband spectrometer. Methylene chloride was dried by distillation from phosphorus pentoxide. Tri ethylamine (TEA), pyridine and THF were dried by distillation from lithium aluminium hydride. Dimethylformamide (DMF) was purified by distillation from barium oxide. Samples for NMR were either dissolved in CDCl3 or CD3CN and treated with 1.5 equivalents of phenylhydrazine or dissolved in 1:1 D2O:acetone-d6 and treated with 1.5 equivalents of sodium dithionite to convert the nitroxide to the hydroxylamine prior to data acquisition (13). Thus, the reported proton and carbon spectra refer to the hydroxylamine derived from the corresponding nitroxides (1–7). Unmodified phosphoramidite DNA bases and CPG resins were obtained from Glen Research (Sterling, VA). Mass spectra (MS) were recorded on an Agilent 5973N (low resolution) or a Finnigan MAT 90 (high resolution).

Phosphoramidite synthesis

5-(2,2,6,6-Tetramethyl-4-ethynylpiperidyl-3-ene-1-oxyl)-uridine (7). Spin probe nitroxide 6 (0.41 g, 2.35 mmol) (12) was added to a solution of 5-iodo-2′-deoxyuridine (5-IdU) (1 g, 2.8 mmol) in DMF (17 ml). The mixture was placed in the dry-ice/methanol bath and exposed to three freeze–thaw cycles, applying a vacuum between freezing and thawing of the reaction mixture, to deoxygenate. Copper iodide (0.67 g, 3.5 mmol) and tetrakis(triphenyl-phosphine)palladium(0) (0.42 g, 0.36 mmol) were then added followed by a final freeze–thaw cycle. Finally, TEA (0.5 ml, 3.6 mmol) was added to a mixture and the reaction was stirred for 12 h at 25°C (11). The solvents were removed in vacuo, the residue was suspended in 20% methanol–CH2Cl2, and filtered through a plug of silica gel. Chromatography (silica gel, 10% methanol–CH2Cl2) afforded the thymidine analog 7 (0.34 g, 70%) as a yellow gum. IR (CHCl3) cm–1: 3700, 3650, 3400 (b), 2400, 1740, 1700, 1610, 1510, 1250, 1035. 1H NMR (CDCl3, phenylhydrazine) δ (ppm): 1.19 (6H, s), 1.28 (6H, s), 2.16 (2H, m), 2.35 (2H, s), 3.748 (1H, m), 3.803 (1H, m), 3.99 (1H, m), 4.34 (1H, m), 6.212 (1H, t), 6. 256 (1H, s), 8.67 (1H, s). UV (CHCl3) λmax (log ε): 240 (3.86). HRMS calculated for C20H26N3O6: 404.4437. Found: 404.4440.

5-(2,2,6,6-Tetramethyl-4-ethynylpiperidyl-3-ene-1-oxyl)-5′-(4,4′-dimethoxyltriphenyl)-uridine (8). The thymidine analog 7 (1.3 g, 3.2 mmol) was added to 4,4′-dimethoxytriphenylmethyl chloride previously dissolved in pyridine (10 ml). The reaction was stirred for 2 h under N2 at 25°C, quenched by the addition of methanol (5 ml), concentrated in vacuo, and purified by column chromatography (silica gel, 5% methanol–CH2Cl2) to give the monoprotected nucleoside 8 (1.95 g, 80%) as a yellow solid. IR (CCl4) cm–1: 3695, 3620, 3395 (b), 3020, 3010, 2990, 2402, 1715, 1705, 1610, 1510, 1455, 1249, 1035. 1H NMR (CDCl3, phenylhydrazine) δ (ppm): 1.60 (6H, d), 1.69 (6H, d), 2.66 (2H, s), 2.76 (1H, m), 3.01 (1H, m); 3.719 (1H, d), 3.816 (1H, d), 3.95 (1H, s), 4. 065 (3H, s), 4.075 (3H, s), 4.47 (1H, m), 5.081 (1H, d), 5.781 (1H, s), 6.511 (1H, s), 9.271 (1H, s). UV (CHCl3) λmax (log ε): 257 (s, 4.03), 276 (3.91), 308 (4.00). HRMS calculated for C41H44N3O8: 706.8023. Found: 706.8100.

5-(2,2,6,6-Tetramethyl-4-ethynylpiperidyl-3-ene-1-oxyl)-5′-(4,4′-dimethoxyltriphenyl)-uridine phosphoramidite (2). To a solution of 8 (0.29 g, 0.41 mmol) in 2.5 ml of dry CH2Cl2 were added TEA (143 µl, 1.026 mmol) and 2-cyanoethyl-diisopropylchloro-phosphoramidite (107 µl, 0.45 mmol). The reaction was stirred for 1 h at 25°C and formation of the product was monitored by TLC. A second portion of 2-cyanoethyl-diisopropylchloro-phosphoramidite was then added (39 µl, 0.17 mmol) and stirred for another hour. The reaction mixture was concentrated in vacuo, THF:benzene (1:4, 2 ml) added and stirred for 10 min. The precipitate was removed by filtration, the filtrate was concentrated in vacuo, and the residue co-evaporated twice with benzene (3 ml). Chromatography on silica gel (petroleum-ether:EtOAc:TEA, 50:50:1) afforded phosphoramidite 2 (0.32 g, 86%) as yellow powder. M.p. 158–160°C. IR (CHCl3) cm–1: 3695, 3610, 3020, 3005, 2985, 2450, 1740, 1580, 1506, 1240, 1190, 1175, 1030, 920. 1H NMR (CD3CN, phenylhydrazine) δ (ppm): 1.15/1.17 (6H, s, (CH3)2), 1.33/1.35 (6H, s, (CH3)2), 1.250/1.251 (12H, s, CH(CH3)2), 2.26 (2H, m, CH2), 2.26 (1H, m, H-2′), 2.56 (1H, m, H-2”), 2.63/2.73 (1H, t, J = 6 Hz, CH2CN), 3.56 (1H, m, H-5′), 3.57 (1H, m, H-5”), 3.67/3.71 (1H, m, CH(CH3)2), 3.74 (1H, m, POCH), 3.84 (6H, s, OCH3), 3.92 (1H, m, POCH), 4.23 (1H, m, H-4′), 4.84 (1H, m, H-3′), 5.72 (1H, bs, CH = C), 6.28 (1H, m, H-1′), 6.85 (4H, d, J = 8, ArH-3,3′,5,5′), 7.26 (4H, d, J = 8, ArH-2,2′,6,6′), 7.26–7.39 (4H, m, ArH-2”,3”,5”,6”), 7.42 (1H, dd, J = 2, 8.5 Hz, ArH-4”), 8.4 (1H, bs, NH), 8.78/8.81 (1H, s, H-6). UV (CHCl3) λmax (log ε): 240 (3.86), 275 (3.53), 302 (3.51). HRMS calculated for C50H62N5O9P: 907.0239. Found: 907.0135.

Oligodeoxyribonucleotide synthesis

Large-scale (10–20 µmol) synthesis was conducted on a modified ABI 430A protein synthesizer. The oligonucleotides T15, A15, 5spT15 (T75spTT7) and 6spT15 (T76spTT7) were synthesized using the solid-phase phosphoramidite protocol. In all cases where the spin-labeled thymidine was a part of the oligonucleotide, it was the eighth base. The oligonucleotides were cleaved from the resin by treatment with concentrated NH4OH (28–30%, 12 ml) at room temperature for 1 h and filtered through a 0.2 µm filter disk. The cleavage of protecting groups for the A15 oligonucleotide was accomplished by heating the filtrate at 55°C for 20 h and then dried down on a SpeedVac. Final purification of oligomers was achieved by FPLC using a Bio-Rad TSK DEAE-5-PW column. T15 was purified under isocratic conditions (53% B; buffer A, 10 mM NaOH, pH 11.8; buffer B, 10 mM NaOH, 1 mM NaCl, pH 11.8; flow rate, 7 ml/min, detecting at λ = 260 nm wavelength). A15 was purified with a gradient (20–26% B over 45 min), as were 5spT15 and 6spT15 (40–55% B, 90 min). The oligomers were desalted with reverse-phase Waters Sep-Pak (C-18) cartridges, conditioned with methanol and water and eluted with 60% aqueous methanol.

DNA sample preparation

dsDNAs A15:T15, A:5spT15, A15:6spT15 and txDNAs T15-A15: T15, 5spT15-A15:T15, 6spT15-A15:T15 [Watson–Crick base pair indicated by a colon (:) and Hoogsteen base-paired strand by a hyphen (-)] were used in the studies presented here. All DNA samples were made up in phosphate buffer (10 mM NaH2PO4, pH 7.4) and sodium chloride (100 mM). Duplex formation was achieved by mixing equivalent amounts of *T15 (*T15 = T15, 5spT15 or 6spT) and A15 [based on optical density (OD)] and, in selected cases, MgCl2, heating to 90°C for 30 min and then slowly cooling to room temperature. txDNAs are prepared by first forming Watson–Crick duplex A15:T15 in the same manner as described above, then adding the third strand, *T15 (*T15 is either 5spT15 or 6spT15) to the duplex and then stored at 4°C for 24 h.

UV melting profiles

UV-monitored melting temperature experiments were conducted at 260 nm using a Cary 300 spectrometer on the duplexes A15:T15, A:5spT15, A15:6spT15, and triplexes T15-A15:T15, 5spT15-A15:T15, 6spT15-A15:T15, under the following conditions: 10 mM NaPO4, 100 mM NaCl pH 7.4, and 10 or 50 mM MgCl2 (∼0.5 OD). Spectra were recorded over a range of 5–90°C at a rate of 0.25°C/min. Tm values were determined from the maxima of the first derivative of the thermal denaturation curve. Enthalpies and entropies were calculated from van’t Hoff plots. All calculations were performed using the vendor supplied software (Win UV Thermal, Ver. 2.00). Error estimates of 10% for the thermodynamic parameters were based on: (i) the range of values obtained from three individual samples for each duplex studied and (ii) reproducibility of the values obtained by computer fit of the data as there is some dependence of the computed values on the range of data selected.

Circular dichroism measurements

The CD spectra were recorded on an AVIV Model 62A CD spectrometer. Solutions were ∼20–30 µM in duplex and triplex. Unless otherwise stated, solutions were prepared in 10 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, and 100 mM NaCl. Magnesium ion concentrations of either 10 or 50 mM were achieved by the addition of aliquots of 1.75 M MgCl2 to the solution of the duplex or triplex. The final sample volume was 400 µl. Spectra were recorded as function of temperature every 5°C from 30 to 75°C for dsDNAs and from 5 to 75°C for txDNAs.

EPR measurements

Continuous wave (CW) EPR spectra were obtained on a Brucker EMX X-band or Varian E-12 spectrometer. Samples were dissolved in phosphate buffer and loaded either in glass capillaries (10 µl) or in a flat cell at oligonucleotide concentrations of ∼2 mM in single-stranded (ssDNA), dsDNA or txDNA. Spectra were acquired at either 0 or 25°C under the conditions noted in the figure captions.

EPR simulation

Computer simulation of EPR spectra were performed using non-linear-least-squares fitting routine with modified Levenberg–Marquardt algorithm in a slow-motion regime (8). Average rotational diffusion rate, rotational anisotropy and Gaussian inhomogeneous line broadening are varied to get the best fit. Goodness-of-fit was determined from the chi-squared value, which represents the sum of weighted residuals, and the correlation factor between the experimental data and the calculated spectrum. Visual judgement of the fit was also taken into account. The program requires values for the g-values (gx, gy and gz) and hyperfine coupling constants (ax, ay and az for nitrogen). Initial values were taken from Hustedt et al. (14). Measurements on frozen samples of T15 and A15:*T15 at 95 GHz were made to confirm these quantities. As no significant difference was observed, the values used by Hustedt were used.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Synthesis of phosphoramidites 1 and 2

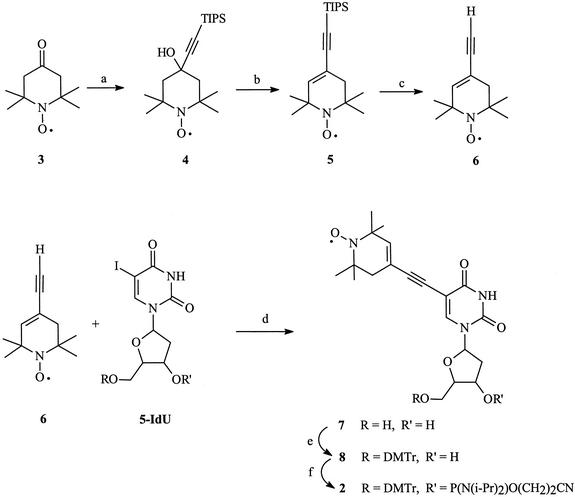

The synthesis of phosphoramidite 1 (Fig. 1) has been previously reported and the published procedures were followed (11). The full synthesis of phosphoramidite 2 has not been previously reported and is shown in Figure 2 (12). The synthesis of this compound began with the commercially available nitroxide 3. This compound was condensed with the lithium salt of triisopropylsilylacetylene in THF to give the acetylenic alcohol 4. The alcohol was then eliminated to the enyne 5, and the triisoproylsilyl group then removed by treatment with tetrabutylammonium fluoride in wet THF to give 6. Next, 6 was coupled to 5-iodouridine to give the nucleoside 7. Attachment of the 5′ and 3′ groups necessary for automated DNA synthesis was accomplished under standard conditions and yielded the phosphoramidite 2.

Figure 2.

Synthetic scheme followed for the preparation of the new spin label phosphoramidite 2. Reaction conditions: (a) TIPS-C≡C-Li, THF, –78°C, (b) SOCl2, pyridine, 0°C, (c) TBAF, THF, (d) Pd[P(C6H5)3)]4, CuI, TEA, DMF, (e) trityl-chloride, TEA, CH2Cl2, (f) Cl-P(OCH2CH2CN)(N(i-Pr)2), TEA, CH2Cl2.

Oligodeoxynucleotide synthesis and purification

Oligonucleotides were prepared using the phosphoramidite methodology on CPG and the standard reaction cycle. The coupling efficiencies were 98–99% for both unmodified and modified oligonucleotides based on the ODs of the isolated oligonucleotides. However, FPLC of the 5spT15- or 6spT15-modified oligonucleotides showed the presence of three oligonucleotides. The major product was the oligonucleotide with an intermediate retention time (42.5 min for 5spT15; 42.0 min for 6spT15). These products correspond to the 15mer oligonucleotide containing the spin label and both gave an ESR signal. The oligonucleotides isolated with the longer retention times (43.7 min for 5spT15; 44.7 min for 6spT15) did not give EPR signals directly, but did following the addition of hydrogen peroxide. FPLC of these EPR samples showed that the EPR silent species eluting at 43.7 min for 5spT15 or 44.7 min for 6spT15 were converted to the EPR active species eluting at 42.5 min for 5spT15 or 42.0 min for 6spT15. Thus, the EPR silent oligonucleotides with a longer retention time are the hydroxylamine derivatives of 5spT15 or 6spT15.

The oligonucleotides with shorter retention times (40.4 min for 5spT15; 40.8 min for 6spT15) were EPR silent and did not give rise to an EPR signal upon the addition of hydrogen peroxide. Mass spectral analysis of the latter oligonucleotides revealed that they had a molecular weight of ∼30 less than expected for the spin-label-bearing 15mer. This suggests that this oligonucleotide had lost NO which may occur during the iodine oxidation step. It is known that nitroxides are sensitive to oxidation by halogens and are converted to nitrones, which can subsequently decompose with the loss of NO (15). This point was further investigated by stopping the oligonucleotide synthesis after the addition of the spin label, T7*T, after the 12th base, T7*TT4, and after the 15th base, T7*TT7 (*T = 5spT or 6spT, *T always located at the eighth position), cleaving from the resin, and examining by FPLC and EPR. FPLC of T7*T showed mainly one oligonucleotide and it was EPR active. As the number of synthesis cycles continued to 12 and then 15, increasing amounts of the oligonucleotide which had lost the NO group appeared, consistent with the hypothesis that the iodine oxidation step is responsible for decomposing the nitroxide. Thus, oxidants, other than iodine, may improve the purity of spin-labeled oligonucleotides prepared by automated DNA synthesis.

Thermal denaturation studies

Thermal denaturation curves of dsDNA and txDNA without and with spin-label modification were measured. These studies were conducted for several reasons. First, thermal denaturation data for unmodified and spin-labeled oligonucleotides have been previously measured on CGCGAATTCGCG and CGCGAAT5spTCGCG duplexes (11). Nearly identical Tm values were determined, indicating that the spin-label modification did not significantly alter the stability of duplex. Here, we wanted to determine if this was also the case for the dsDNAs A15:5spT15 and the A15:6spT15 and the triplexes 5spT15-A15:T15 and the 6spT15-A15:T15. In addition, it was necessary to measure the temperature at which the spin-labeled duplexes and triplexes melted so that the temperature at which the EPR studies should be conducted could be determined.

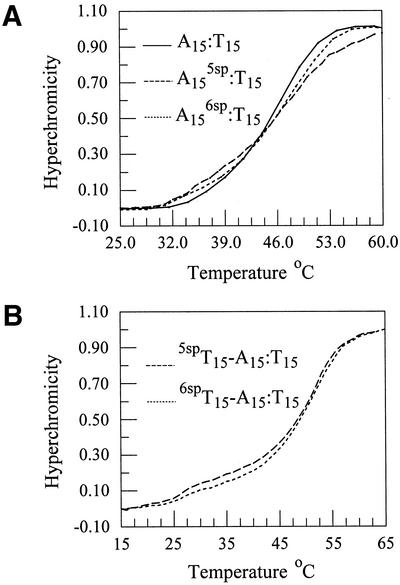

The dsDNA thermal denaturation curves were obtained on samples made up in 10 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) and 100 mM sodium chloride to which magnesium chloride was added. Representative curves are shown in Figure 3A. Thermal denaturation and thermodynamic data for all magnesium chloride concentrations are shown in Table 1. There are no significant differences in the Tm values measured for the unmodified and modified dsDNAs though the shape of the profiles suggests some differences in the degree of cooperativity as the dsDNAs melt. Likewise, the thermodynamic parameters for the unmodified and modified oligonucleotides are all nearly identical. Though not statistically significant, the general trend suggests that the modified oligonucleotides are slightly more stable. The values reported here for Tm, ΔG°, ΔH° and ΔS° are comparable to those obtained computationally from the program MELTING (16).

Figure 3.

Thermal denaturation curves for (A) dsDNAs A15:T15 (solid line), A15:5spT15 (dashed line) and A15:6spT15 (dotted line) and (B) the txDNAs 5spT15-A15:T15 (dashed line) and 6spT15-A15:T15 (dotted line). All samples were dissolved in 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer pH 7.4, 100 mM NaCl and 50 mM MgCl2.

Table 1. UV melting temperatures for the unmodified and modified 5spT and 6spT duplexesa.

| Duplex | Tm (°C) | ΔG° (kcal/mol)b | ΔH° (kcal/mol) | ΔS° (cal/mol·K) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A15T15 | 24 | –8.7 | –100 | –312 |

| 35 | –13.5 | –116 | –345 | |

| 45 | –18.8 | –126 | –365 | |

| A15:5spT15c | 25 | –8.7 | –102 | –319 |

| 36 | –14.8 | –118 | –349 | |

| 46 | –19.1 | –134 | –393 | |

| A15:6spT15d | 24 | –8.6 | –100 | –312 |

| 36 | –14.8 | –117 | –353 | |

| 45 | –18.9 | –127 | –369 |

aDNA melting temperatures were measured in solutions of ∼0.5 OD oligonucleotide in sodium phosphate buffer (10 mM, pH 7.4) and sodium chloride (100 mM). Tm values were determined from the maxima of the first derivative of the thermal denaturation curve.

bFree energies calculated at 293 K. Errors in the thermodynamic data are estimated to be ∼10% (see Materials and Methods).

cSamples also contained 10 mM MgCl2.

dSamples also contained 50 mM MgCl2.

Thermal denaturation curves of the txDNAs (*T15-A15:T15; *T is the third, triplex strand, A15:T15 is the Watson–Crick base-paired dsDNA) were also measured. Two Tm values, identified by determining the maxima of the first derivative of the thermal denaturation curve, are observed for txDNAs. The first value corresponds to the triplex melting to give a single-stranded oligonucleotide, *T15 (*T15 = T15, 5spT15 or 6spT15) and a dsDNA (A15:T15) and the second Tm for the melting of the duplex. The Tm for the triplex melting is not always observed, in part due to the small difference in absorbance between the triplex and the duplex in the presence of an unassociated triplex strand (17). However, at relatively high concentrations of magnesium chloride, conditions known to stabilize txDNA (18), two transitions can be observed for all three triplexes as shown in Figure 3B. In Table 2 are reported the Tm values for the unmodified and modified txDNAs. As was observed for the dsDNAs, they do not significantly differ from one another under a given set of conditions. Thermodynamic parameters could not be extracted from the data as there was not a sufficient break between the triplex and duplex portions of the melting curves.

Table 2. UV melting temperatures for the unmodified and modified 5spT and 6spT triplexesa.

| txDNA | Tm (°C) 10 mM Mg2+ | Tm (°C) 50 mM Mg2+ |

|---|---|---|

| T15-A15:T15 | 20 | 26 |

| 5spT15-A15:T15 | 19 | 26 |

| 6spT15-A15:T15 | 19 | 26 |

aOnly the melting temperature (Tm) of the triplex is reported. DNA melting temperatures were measured on solutions of ∼0.5 OD oligonucleotide in sodium phosphate buffer (10 mM, pH 7.4) and sodium chloride (100 mM).

Within experimental error, there is no significant difference in the thermal denaturation temperatures determined for the all three duplexes or triplexes. This indicates that the replacement of T with either 5spT or 6spT has little, if any, effect on the overall stability of either the duplexes or triplexes of which they are a part. This is further supported by the CD and EPR studies (see below). In addition, the thermal denaturation data allow the determination of which species (triplex, duplex or single-stranded) are present at a given temperature aiding the interpretation of both the CD and EPR data.

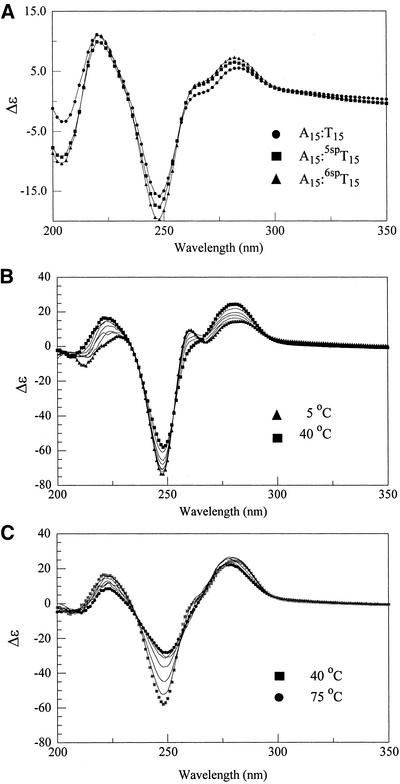

Circular dichroism

CD spectroscopy has been shown to be a useful tool to distinguish between homopolymer A:T duplexes and T-A:T triplexes. We have used CD spectra here for three main purposes. First, we used CD to show that the A15:T15 duplex and T15-A15:T15 triplex are present by comparison with previously published data. Secondly, for the spin labels to be useful for biological studies, it is important to demonstrate that they do not produce any significant conformational changes and thus give rise to CD spectra comparable with unmodified oligonucleotides. Finally, CD data can be used to detect the presence of the triplex form, the duplex form, and the temperature-dependent conversion of the former to the latter. Thus, the methodology can be used as an alternative to, or supplement to, the thermal denaturation data.

In Figure 4A are shown the CD curves for A15:T15, A15:5spT15 and A15:6spT15. Overall, the curves are quite similar to one another and show positive ellipticity at 218 and 282 nm and negative ellipticity at 248 and 210 nm (19,20). There are some noticeable differences between the unmodified and spin-labeled duplexes. In particular, the spin-labeled duplexes produce larger positive ellipticities at 218 and 282 nm and more negative ellipticities at 210 and 248 nm than do the unmodified duplexes. While the source of these differences is unknown, they may be due to differences in the light-absorption properties of the spin label, to changes in secondary structure, or a combination of both (21). Molecular dynamics calculations on the unmodified and modified dsDNAs have shown that both adopt a B-DNA-like structure. However, the unmodified duplex more closely resembles canonical B-DNA while the modified dsDNAs are beginning to resemble A-DNA (22). The differences observed in the CD spectra between the unmodified and modified DNAs support this as A-DNAs show more positive ellipticities at ∼280 nm and more negative ellipticities at ∼210 nm (21). Thus, the shape of the CD curves and the observed minima and maxima indicate that there are some secondary structural differences, though probably small, and both unmodified and modified dsDNAs adopt a B-DNA-like conformation.

Figure 4.

CD spectra of (A) A15:*T15, where *T15 is T15 (circles), 5spT15 (squares), and 6spT15 (triangles) at 25°C, (B) 6spT15-A15:T15 triplex recorded from 5°C (triangles) to 40°C (squares), and (C) 6spT15-A15:T15 triplex sample in (B) from 40°C (squares) to 75°C (circles). All samples were dissolved in 10 mM phosphate buffer pH 7.4, 100 mM NaCl and 50 mM MgCl2.

As noted, CD spectra can be used to distinguish between txDNA and dsDNA for homopolymers of T-A:T and A:T, respectively (23). Here, we have used CD for this purpose and have measured the CD spectra of samples of *T15-A15:T15 (*T15 = T15, 5spT15 and 6spT15). Figure 4B shows a series of CD spectra recorded on a sample containing 6spT15-A15:T15 over the temperature range of 5–40°C. Among the key features to note are that at 5°C, there are maxima at 230, 260 and 284 nm, minima at 210, 248 and 267 nm, and an isoelliptic point at 263 nm. These spectral features are very similar to 5spT15-A15:T15 (data not shown) and to those previously reported CD spectra of T-A:T triplexes and strongly support the presence of a txDNA in our samples.

As the sample is warmed, the maxima at 230 and 284 nm increase while the maxima at 260 nm gradually diminishes in amplitude. The maxima at 230 and 284 nm shift toward shorter wavelengths although the shift for the 230 nm peak is much larger than that for 284 nm. The minimum at 248 nm is seen to decrease in amplitude but its position remains constant. In total, these observations are completely analogous to those reported for T12-A12:T12 (19,20). Moreover, the unmodified T15-A15:T15 and 5spT15-A15:T15 triplexes give CD spectra (data not shown) that were nearly identical to those presented in Figure 4B.

Upon raising the temperature from 40 to 75°C a new set of spectral changes occur (Fig. 4C). First, several of the characteristics of the spectrum at 40°C, where the dsDNA form should be the main species present, are quite different from those observed at 5°C. The short wavelength maximum is significantly blue shifted (230 → 218 nm) and the maximum at 260 nm is no longer present. However, the maximum at 282 nm and the minimum at 248 nm are still present though both have diminished in intensity. Raising the temperature produces smaller changes in the two maxima, relative to those seen for the triplexes. In contrast, the relative change seen for the minima at 248 nm is larger on heating the duplex than that observed for the triplex.

The spectra shown in Figure 4B and C are very similar to the CD spectra for T15-A15:T15 and 5spT15-A15:T15 (data not shown). The data suggest that neither the 5spT nor the 6spT spin labels significantly affect the structure or conformation of the triplex of which they are a part. Likewise, the temperature dependence of all three sets of spectra is very similar and supports the position that the spin-label modified thymidine is nearly identical to a thymidine that it replaces.

EPR studies

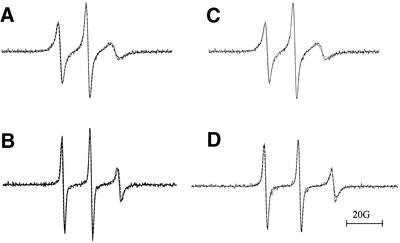

The EPR spectrum of 5spT15, at 0°C, is shown in Figure 5A. This spectrum shows slight anisotropic broadening in the high field line as has been previously observed (11) for the 12mer analog with the spin probe 1, located on the sixth base. Here, the spectra for 5spT15 were fitted using the program NLSL and the computer fit is also shown (dashed line) (8). The fitting procedure provides the average correlation time (τc), a measure of mobility for the spin label, with shorter times indicating greater mobility. These times are reported for both 0 and 25°C temperatures.

Figure 5.

EPR spectra of (A) 5spT15 at 0°C, (B) 5spT15 at 25°C, (C) 6spT15 at 0°C and (D) 6spT15 at 25°C. All spectra were recorded on samples that were dissolved in 10 mM phosphate buffer pH 7.4, 100 mM NaCl and 50 mM MgCl2. Spectrometer settings: receiver gain 6.32 × 103, sweep width 100 G, modulation amplitude 1.00 G, modulation frequency 100 kHz, microwave power 20 mW, time constant 5.12 ms. The solid line is the experimental spectrum and the dashed line is the simulated spectrum.

As spectra become more anisotropic, meaning that the motion of the probe slows, it is more appropriate to calculate the two components of correlation time, τ⊥ and τ||, since they are related to the rotational rate constants R⊥ and R||. As the motion slows, the spectrum becomes more sensitive to R|| and less sensitive to R⊥. The correlation time obtained for the ssDNA was ∼3 ns, slightly longer than the correlation time reported for the 12mer (1 ns). Warming the sample to room temperature gives the spectrum shown in Figure 5B. The spectrum is similar to that obtained at 0°C (Fig. 5A) though the upfield line has sharpened and the correlation time has decreased to ∼1 ns.

The EPR spectrum of the 6spT15 spin-labeled oligonucleotide is also shown (Fig. 5C). This spectrum is nearly indistinguishable from that of 5spT15 and the correlation time obtained by computer simulation of the spectrum confirms this (Tables 3 and 4). As was observed for the 5spT15 spin probe, warming the sample causes the high field line to sharpen. Fitting the spectrum shows that the correlation time has decreased by a factor of 3 to ∼1 ns (Tables 3 and 4), as observed for the 5spT15 spin probe.

Table 3. Correlation times for ssDNA, dsDNA and txDNA containing 6spT spin labela.

| 6spT | 6spT:A | 6spT-A:T | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| One species | One species | Two species | One species | Two species | |||||

| Fast | Slow | Fast | Slow | ||||||

| 0°C | 3.03 | 167 | 10.5 | 157 | 170 | 4.83 | 307 | ||

| τ⊥ | 4.056 | 38.57 | 62.89 | 109.5 | 53.40 | 30.78 | 38.73 | ||

| τ|| | 2.111 | 74.00 | 8.615 | 245.2 | 151.6 | 4.006 | 3570 | ||

| N%b | 100 | 100 | 47 | 53 | 100 | 5 | 95 | ||

| 25°C | 1.07 | 10.7 | 0.33 | 25.7 | 0.95 | 0.60 | 18.3 | ||

aCorrelation times are expressed in nanoseconds, and they were determined by simulation of the experimental EPR data using the program NLSL, unless otherwise noted.

bN% refers to the percentages of each species present.

Table 4. Correlation times for ssDNA, dsDNA and txDNA containing 5spT spin labela.

| 5spT | 5spT:A | 5spT-A:T | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| One species | One species | Two species | One species | Two species | |||

| Fast | Slow | Fast | Slow | ||||

| 0°C | 2.97 | 163 | 11.6 | 88.3 | 163 | 3.25 | 303 |

| τ⊥ | 4.430 | 87.55 | 4.849 | 77.54 | 24.65 | 3.534 | 32.32 |

| τ|| | 1.791 | 156.4 | 18.18 | 196.4 | 548.3 | 0.724 | 3265 |

| N%b | 100 | 100 | 45 | 55 | 100 | 7 | 93 |

| 25°C | 1.15 | 9.33 | 0.43 | 14.3 | 1.03 | 0.68 | 26.7 |

aCorrelation times are expressed in nanoseconds, and, unless otherwise noted, they were determined by simulation of the experimental EPR data using the program NLSL.

bN% refers to the percentages of each species present.

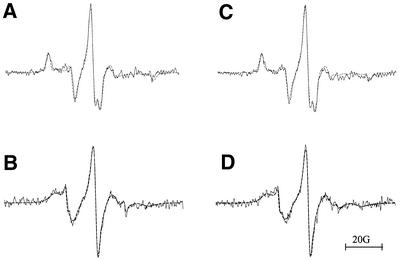

Duplexes with A15 and 5spT15 or 6spT15 were prepared (10 mM phosphate buffer pH 7.4, 100 mM NaCl) and the EPR spectra of these samples recorded at 0 and 25°C (Fig. 6). The spectra were simulated to calculate τc for both spin labels and at both temperatures. It has been shown that duplex formation significantly reduces the mobility of attached spin labels and the spectra become very anisotropic as can be seen by comparison of the EPR spectra in Figures 5 and 6. The spectra in Figure 6 were each fit assuming either (i) that only the duplex was present or (ii) that two species were present, the duplex and, for example, some dissociated *T15. The former assumption gives correlation times that are nearly identical for the duplexes containing 5spT or 6spT, 163 and 167 ns, respectively (Tables 3 and 4).

Figure 6.

EPR spectra of (A) A15:5spT15 at 0°C, (B) A15:5spT15 at 25°C, (C) A15:6spT15 0°C and (D) A15:6spT15 25°C. All spectra were recorded on samples that were dissolved in 10 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.4), 100 mM NaCl and 50 mM MgCl2. Spectrometer settings were the same as those used for the data in Figure 5. The solid line is the experimental spectrum and the dashed line is the simulated spectrum.

The two species fit results in two correlation times for each spectrum (5spT15 or 6spT15), one corresponding to a conformationally more mobile species (fast) and one that is more constrained (slow, duplex). While the two species assumption gave statistically improved fits for each spectrum, this is likely an artifact of the process. There are several reasons for this statement. First, the most likely candidate for the fast species is the single-stranded oligonucleotide bearing the spin probe. If so, then the computed correlation times for the fast species should be the same as for the ssDNAs in the absence of A15. This is not the case as the fast species have correlation times approximately three times larger (Tables 3 and 4). The results at room temperature are similar to those obtained at 0°C. Finally, the sub-spectra that correspond to the fast species do not resemble the single-stranded oligonucleotide (data not shown).

Note, that while the correlation times for the single-stranded oligonucleotides are quite similar to those reported for 5spT12, those found here for the duplexes are larger, by a factor of 10, than those reported for 5spT12A12. The discrepancy may be due to the different methods used to fit the data or to differences in the conditions used. The correlation times for 5spT12:A12 were obtained by treating the duplex as a cylinder to which the probe was attached and analyzed using hydrodynamic theory. Here we have used the MOMD method for simulation (24). Which method is more appropriate for these systems is debatable. However, the basic conclusions are not affected.

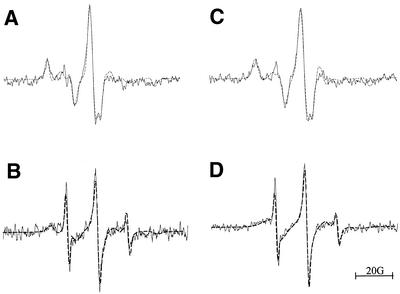

Spin labels have been used to study a variety of DNA structures including dsDNA, loops (both stem and helical regions), and base-pair mis-matches and bulges (4–7). To our knowledge, they have not been used to detect txDNA formation. Here, we show that spin labels can also be used for this purpose. The duplex between A15 and T15 was prepared (A15:T15) and to this duplex was added either 5spT15 or 6spT15. After annealing overnight at 4°C, under conditions known to produce txDNA (5spT15-A15:T15 or 6spT15-A15:T15), the EPR were recorded at 0°C and at room temperature. The resulting EPR and spectral simulations are shown in Figure 7. It is obvious that the spectra obtained at 0°C are anisotropic and the mobility of the strand has been constrained. This, in turn, implies that the third strand has become bound to its target and thus the EPR spectra shown in Figure 7 are those of txDNA. In addition, the thermal denaturation and CD data support this claim.

Figure 7.

EPR spectra of (A) 5spT15-A15:T15 at 0°C, (B) 5spT15-A15:T15 at 25°C, (C) 6spT15-A15:T15 at 0°C and (D) 6spT15-A15:T15 at 25°C. All spectra were recorded on samples that were dissolved in 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4), 100 mM NaCl and 50 mM MgCl2. Spectrometer settings were the same as those used for the data in Figure 5. The solid line is the experimental spectrum and the dashed line is the simulated spectrum.

The triplex EPR data were fit as described for the duplexes, fitting the data assuming either one or two species to be present. As in the case of the duplexes, the fits were improved for the two species fits and the calculated correlation times are shown in Tables 3 and 4. However, unlike the duplexes, the correlation times obtained for the fast species agree with those obtained for the single-stranded oligonucleotides. This suggests that, in this case, the two-species fit is a better choice. Moreover, the calculated sub-spectra for 6spT15-A15:T15 (0°C) confirm this and the calculated spectrum for the fast species is essentially the same as the spectrum that is calculated for 6spT15 at 0°C (Fig. 5C).

The triplex simulations that were based on two sites give correlation times that are twice those for the duplexes (single species fit). This increase in correlation time suggests that txDNA may be more rigid than dsDNA. Alternatively, the difference may simply be due to the increased size of the triplex relative to the duplex. It is difficult to distinguish between these two possibilities and to do so will require additional studies to determine which factor is responsible for the difference. In addition, molecular modeling and molecular dynamics calculations may further help to resolve this question.

Finally, the temperature dependence of the triplex EPR data addresses whether the spectra in Figure 7 are txDNA with the spin-labeled strand as the Hoogsteen or the Watson–Crick base-paired strand. There is some ambiguity in this regard as the spin-labeled strand, with the exception of the spin label, is identical with the T15 Watson–Crick base-paired strand. Therefore, since the 5spT15 or the 6spT15 strand could have exchanged with the T15 strand, the EPR spectra shown in Figure 7 might correspond to T15-A15:5spT15 or T15-A15:6spT15 instead of 5spT15-A15:T15 or 6spT15-A15:T15. This seems unlikely as samples were maintained at 4°C or below, except to obtain the room temperature spectrum, conditions where the duplex (A15:T15) is stable (Tm ∼ 45°C). More important are the EPR spectra. As the txDNA samples are warmed to room temperature (Fig. 7B and D), the spectra change to the spectrum of mainly 5spT15 or 6spT15. If strand exchange had occurred then warming the txDNA samples to room temperature would have lead to the same spectra as obtained for dsDNAs A15:5spT15 or A15:6spT15. Comparison of the spectra shown in Figure 6B and D with those in Figure 7B and D shows that this is clearly not the case.

CONCLUSIONS

The synthesis of a new spin label nitroxide in a six-membered ring, which is rigidly attached to a uridine, has been achieved and its preparation described. This new spin-labeled DNA base, 2, is synthetically more simple to prepare than a previously described, analogous spin label, 1, and, at the same time, provides comparable yields during automated DNA synthesis and similar EPR data. The effect of the spin label on the thermal denaturation temperature for dsDNA and txDNA is minimal and unmodified and modified DNAs have similar Tm and thermodynamic properties suggesting that the spin labels do not significantly alter the stability of dsDNAs or txDNAs that contain them. CD spectra of the unmodified and modified dsDNAs are similar, though there are some differences that suggest the spin labels may perturb the secondary structure and render it more A-DNA-like than is the unmodified dsDNA. The CD spectra also show that the modified DNAs can form txDNA. The EPR spectra show that the new spin label can be used to monitor dsDNA formation and, in addition, both spin labels can be used to detect txDNA as well. The EPR data suggest that the spin label in txDNA is slightly less mobile than dsDNA though this may be due to the increase in size of the txDNA relative to the dsDNA.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We thank the Florida State University BASS laboratory for their assistance in the preparation and purification of the oligonucleotides used in the course of this work. C.M. is a UNCF-Pfizer Biomedical Research Fellow. We thank the NIH (GM 57630) and NSF-EPSCoR (9871948) for their financial support of this work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bobst A.M., Kao,S.-C., Toppin,R.C., Ireland,J.C. and Thomas,I.E. (1984) Dipsticking the major groove of DNA with enzymatically incorporated spin-labeled deoxyuridines by electron spin resonance spectroscopy. J. Mol. Biol., 173, 63–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pauly G.T., Thomas,I.E. and Bobst,A.M. (1987) Base dynamics of nitroxide-labeled thymidine analogues incorporated into (dA–dT)n by DNA polymerase I from Escherichia coli. Biochemistry, 26, 7304–7310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Strobel O.K., Kryak,D.D., Bobst,E.V. and Bobst,A.M. (1991) Preparation and characterization of spin-labeled oligonucleotides for DNA hybridization. Bioconjugate Chem., 2, 89–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Keyes R.S. and Bobst,A.M. (1993) A comparative study of Scatchard-type and linear lattice models for the analysis of EPR competition experiments with spin-labeled nucleic acids and single-strand binding proteins. Biophys. Chem., 45, 281–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Strobel O.K., Keyes,R.S., Sinden,R.R. and Bobst,A.M. (1995) Rigidity of a B-Z region incorporated into a plasmid as monitored by electron paramagnetic resonance. Arch. Biochem. Biophys., 324, 357–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keyes R.S., Bobst,E.V., Cao,Y.Y. and Bobst,A.M. (1997) Overall and internal dynamics of DNA as monitored by five-atom-tethered spin labels. Biophys. J., 72, 282–290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liang Z., Freed,J.H., Keyes,R.S. and Bobst,A.M. (2000) An electron spin resonance study of DNA dynamics using the slowly relaxing local structure model. J. Phys. Chem. B, 104, 5372–5381. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Budil D.E., Lee,S., Saxena,S. and Freed,J.H. (1996) Nonlinear-least-squares analysis of slow-motion EPR spectra in one and two dimensions using a modified Levenberg–Marquardt algorithm. J. Magn. Res., Ser. A, 120, 155–189. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Qin P.Z., Butcher,S.E., Feigon,J. and Hubbell,W.L. (2001) Quantitative analysis of the isolated GAAA tetraloop/receptor interaction in solution: a site-directed spin labeling study. Biochemistry, 40, 6929–6936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Spaltenstein A., Robinson,B.H. and Hopkins,P.B. (1989) DNA structural data from a dynamics probe. The dynamic signatures of single-stranded, hairpin-looped and duplex forms of DNA are distinguishable. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 111, 2303–2305. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spaltenstein A., Robinson,B.H. and Hopkins,P.B. (1989) Sequence- and structure-dependent DNA base dynamics: synthesis, structure and dynamics of site and sequence specifically spin-labeled DNA. Biochemistry, 28, 9484–9495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gannett P.M., Darian,E., Powell,J.H. and Johnson,E.M. (2001) A short procedure for synthesis of 4-ethynyl-2,2,6,6-tetramethyl-3,4-dehydro-piperidine-1-oxyl nitroxide. Syn. Commun., 31, 2137–2141. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ozinskas A. and Bobst,A.M. (1980) Formation of N-hydroxy-amines of spin labeled nucleosides for 1H-NMR analysis. Helv. Chim. Acta, 63, 1407–1411. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hustedt E.J., Kirchner,J.J.S.A., Hopkins,P.B. and Robinson,B.H. (1995) Monitoring DNA dynamics using spin-labels with different independent mobilities. Biochemistry, 34, 4369–4375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rozantsev E.G. and Sholle,V.D. (1971) Synthesis and reactions of stable nitroxyl radicals. II. Reactions. Synthesis, 401–414. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Le Novere N. (2001) MELTING, computing the melting temperature of nucleic acid duplex. Bioinformatics, 17, 1226–1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chan S.S., Breslauer,K.J., Hogan,M.E., Kessler,D.J., Austin,R.H., Ojemann,J., Passner,J.M. and Wiles,N.C. (1990) Physical studies of DNA premelting equilibria in duplexes with and without homo dA·d(T) tracts: correlations with DNA bending. Biochemistry, 29, 6161–6171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Singleton S.F. and Dervan,P.B. (1993) Equilibrium association constants for oligonucleotide-directed triple helix formation at single DNA sites: linkage to cation valence and concentration. Biochemistry, 32, 13171–13179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Durand M., Peloille,S., Thuong,N.T. and Maurizot,J.C. (1992) Triple-helix formation by an oligonucleotide containing one (dA)12 and two (dT)12 sequences bridged by two hexaethylene glycol chains. Biochemistry, 31, 9197–9204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Purrello R., Molina,M., Wang,Y., Smulevich,G., Fossella,J., Fresco,J.R. and Spiro,T.G. (1993) Keto iminol tautomerism of protonated cytidine monophosphate characterized by ultraviolet resonance Raman spectroscopy: implications of C+ iminol tautomer for base mispairing. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 115, 760–767. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnson W.C. (2000) Chapter 24. In Berova,N., Nakanishi,K. and Woody,R.W. (eds), Circular Dichroism: Principles and Applications. John Wiley and Sons, New York, pp. 703–718.

- 22.Darian E. (2002) Triplex formation as monitored by EPR spectroscopy and molecular dynamics studies of spin-probe labeled DNAs. Dissertation, West Virginia University, pp. 66–112 (http://etd.wvu.edu//ETDS/E2591/Darian_Eva_dissertation.pdf).

- 23.Herrera J.E. and Chaires,J.B. (1989) A premelting conformational transition in poly(dA)–poly(dT) coupled to daunomycin binding. Biochemistry, 28, 1993–2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liang Z. and Freed,J.H. (1999) An assessment of the applicability of multifrequency ESR to study the complex dynamics of biomolecules. J. Phys. Chem. B, 103, 6384–6396. [Google Scholar]