Abstract

Aberrant or modified splicing patterns of genes are causative for many human diseases. Therefore, the identification of genetic variations that cause changes in the splicing pattern of a gene is important. Elsewhere, we described the widespread occurrence of alternative splicing at NAGNAG acceptors. Here, we report a genomewide screen for single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) that affect such tandem acceptors. From 121 SNPs identified, we extracted 64 SNPs that most likely affect alternative NAGNAG splicing. We demonstrate that the NAGNAG motif is necessary and sufficient for this type of alternative splicing. The evolutionarily young NAGNAG alleles, as determined by the comparison with the chimpanzee genome, exhibit the same biases toward intron phase 1 and single–amino acid insertion/deletions that were already observed for all human NAGNAG acceptors. Since 28% of the NAGNAG SNPs occur in known disease genes, they represent preferable candidates for a more-detailed functional analysis, especially since the splice relevance for some of the coding SNPs is overlooked. Against the background of a general lack of methods for identifying splice-relevant SNPs, the presented approach is highly effective in the prediction of polymorphisms that are causal for variations in alternative splicing.

SNPs, as the most abundant form of genetic variation, contribute significantly to phenotypic individuality and disease susceptibility. SNPs are mostly biallelic and are therefore easy to assay once they are described. Given their abundance in the human genome (∼1 SNP every 300 bp [Ke et al. 2004]) and their ease of high-throughput typing, SNPs progressively replace microsatellites as first-choice genetic markers in association and linkage studies.

Much interest focuses on SNPs that are located in coding regions, since those SNPs may alter the protein sequence. However, SNPs can also influence splicing, which usually has a greater effect on the resulting protein than does the alteration of a single codon. Recently, splicing mutations have been suspected to be the most frequent cause of hereditary diseases (Lopez-Bigas et al. 2005). Accordingly, an increasing number of SNPs have been described that cause diseases by a change or disruption of the normal splicing pattern (for review, see Cartegni et al. [2002] and Garcia-Blanco et al. [2004]). These splice-relevant SNPs affect donor and acceptor splice sites, branch points, exonic as well as intronic splicing enhancers and silencers or alter important mRNA secondary structures. For example, the G allele of the silent coding SNP rs17612648 in the PTPRC gene that is associated with multiple sclerosis destroys an exonic splicing silencer and abolishes the skipping of exon 4 (Lynch and Weiss 2001), and the SNP rs2076530 in BTLN2 that is associated with sarcoidosis leads to the activation of a cryptic donor site and a cryptic donor splice site 4 nt upstream (Valentonyte et al. 2005). Since the impact of SNPs on splicing is hard to predict in silico and is difficult to analyze experimentally, silent or intronic SNPs that may cause a phenotype or a disease by changing splicing patterns are often not investigated (Pagani and Baralle 2004). Thus, novel approaches are urgently needed to identify splice-relevant SNPs.

Recently, we reported the widespread occurrence of subtle alternative splice events that insert or delete the sequence NAG (N denotes A, C, G, or T) in mRNA (Hiller et al. 2004). This happens if both AG alleles of a NAGNAG acceptor can be chosen by the spliceosome. We termed the upstream acceptor in this tandem motif the “E acceptor” and the downstream one the “I acceptor.” The products that arise from the use of E and I acceptors are called “E and I transcripts and proteins,” respectively. The consequences of NAG insertion/deletions (indels) in mRNAs for the respective protein sequences are highly diverse and comprise eight different single–amino acid (aa) indel events, the exchange of a dipeptide and an unrelated aa, or the creation/destruction of a stop codon. Tandem acceptors are conserved between human and mouse, and the use of E or I acceptors can be controlled in a tissue-specific manner. Our results concerning the frequency and tissue specificity were confirmed by others (Tadokoro et al. 2005). Furthermore, E/I protein isoforms have functional differences (Condorelli et al. 1994; Tadokoro et al. 2005), and the SNP rs1650232 within a NAGNAG acceptor is associated with respiratory-distress syndrome (Karinch et al. 1997).

Since NAGNAG acceptors occur in ∼30% of human genes, we were interested in finding SNPs that may affect this type of alternative splicing. By scanning the SNP annotation of the human reference sequence, we identified those SNPs and provide experimental evidence of respective variations in the alternative splicing patterns. In addition, we introduce a classification for NAGNAG acceptors, with respect to their splicing plausibility, to bring forward a highly effective approach for predicting splice-relevant SNPs.

Methods

Identification of SNPs Affecting NAGNAG Acceptors

We downloaded the human genome assembly from the UCSC Genome Browser (UCSC Human Genome Browser, hg17, May 2004) as well as from RefSeq (refGene.txt.gz, January 12, 2005) and SNP annotations (snp.txt.gz, January 9, 2005). From the transcripts, we extracted a list of unique genomic positions of acceptor sites. We used the genomic position of the acceptors to select those SNPs that overlap the first 3 nt of an exon or the last 6 nt of an intron. Then, we evaluated whether one of both AG alleles or one of the two Ns in the NAGNAG pattern is polymorphic. SNPs are the only type of polymorphisms that were considered.

To check whether a tandem acceptor is EST confirmed, we used BLAST with a search string of 30 nt from the upstream exon and 30 nt from the downstream exon—taking the nonannotated acceptor into account—against the human fraction of the dbEST database (December 2004) and against the mRNA sequences downloaded from GenBank (December 2004). At most, one mismatch or one gap was allowed.

Comparison with the Chimpanzee Genome

We downloaded the chimpanzee genome working draft assembly from UCSC Genome Browser (UCSC Chimpanzee Genome Browser, panTro1, November 2003). We compared human polymorphic sites with the chimpanzee sequence, using BLAST, with 101-nt queries consisting of one of the SNP alleles, as well as 50 nt upstream and 50 nt downstream. Only hits with at least 95% identity and no other mismatch in the −5…+5 context of the SNP were considered.

Null Model for Gain of NAGNAG Acceptors

Briefly described, we determined the ancestral allele variant for 2,439 SNPs that overlap an acceptor in the 9-nt context by comparing the genomic sequence context with the chimpanzee genome. In addition, we selected a set of 8,082 acceptor sites not affected by known SNPs. Then, the 2,439 SNPs were randomly assigned to one of those acceptors, given that the ancestral allele variant is present at the respective position. This position was replaced by the nonancestral allele, and we evaluated and counted the possible impact on a NAGNAG acceptor. More details are given in appendix A.

Experimental Verification of Alternative Splicing at Polymorphic NAGNAG Acceptors

Genomic DNA and cDNA from 12 whites were kindly provided by Gerd Birkenmeier (Leipzig) and were purified from whole blood by standard methods. First-strand cDNA was derived from oligo-dT primed reverse transcription.

For determination of the respective genotypes, ∼20 ng of genomic DNA was used to PCR amplify the regions of the respective SNP through use of Ready-To-Go PCR beads (Amersham). PCR conditions were 1 cycle of denaturation at 95°C for 30 s; followed by 38 cycles of denaturing at 92°C for 30 s, annealing at 59°C for 30 s, and extension at 72°C for 60 s; and 1 cycle of final extension at 72°C for 5 min. PCR products were purified by precipitation and were sequenced with the same primers used for PCR amplification by the dye terminator method by use of BigDye v3.1 (Applied Biosystems). To identify E and I transcripts, cDNA from the genotyped individuals was amplified using the same PCR conditions with transcript-specific primers.

For amplification of genomic DNA and subsequent sequencing of the resulting amplicons that correspond to SNPs listed in table 1, we used primers 5′-CAGCTACGGTTTGCTGAGAA-3′ and 5′-ACAGAGGGGACAGGGAGATT-3′ for genotyping rs2245425, 5′-GATTTTCCTGGAGGAGAGGG-3′ and 5′-CAAGTTCAAAGCAAGCCTCC-3′ for rs1558876, 5′-AGGAGGCGTGCTATCTGGTA-3′ and 5′-GTAGGAAGCCCTGGAGGAAG-3′ for rs2290647, 5′-GCCATTGAGTTGTCATCACC-3′ and 5′-ACCCATTAGCTTGGCAACAG-3′ for rs2275992, 5′-AAGAATGGCGTCCATTTCAC-3′ and 5′-TTTCTGATCCTTGGTGAGGG-3′ for rs4590242, and 5′-CCTTCAACCTCAATGACGAAA-3′ and 5′-CACAAAGGACTTGTCAGGGA-3′ for rs1152522. RT-PCR for transcript amplification was done with primers 5′-GAAAGCGCGTACTACCTTCG-3′ and 5′-AATCCCTGGATCTGGCCTTA-3′ for TOR1AIP1, 5′-AGGCTACAACCACCCTCCTT-3′ and 5′-ACTTCCCCCTTGACGAGTTT-3′ for KIAA1001, 5′-AGAGGAGGACAAGGAGGAGC-3′ and 5′-GAACAGCGTCTGTGTCTCCA-3′ for KIAA1533, 5′-GGACATCTGTTTCTCGCCAT-3′ and 5′-ATCCTTCCATCTCACAACGG-3′ for ZFP91 (GenBank accession number NM_170768), 5′-TCTTTCTTTTGTGGTGGGGA-3′ and 5′-TGTCAGGGACCCAGATCTTC-3′ for GABRR1, and 5′-TGCAGGACCAGAATAAAGCC-3′ and 5′-TATGGTCCCTTGGACTTTGC-3′ for C14orf105. For ZFP91 and TOR1AIP1, the amplicons obtained by RT-PCR from individuals with each of the possible genotypes were cloned into PCR2.1-TOPO (Invitrogen) and were propagated in Escherichia coli TOP10 cells, respectively. Plasmids were isolated from several isolated clones, and their inserts were sequenced using plasmid primers. SNPs exhibiting nonancestral plausible NAGNAGs without EST evidence were selected by high frequencies of the minor alleles rs1638152 (DTX2), rs5248 (CMA1), and rs17105087 (SLC25A21). Genomic primers used were for DTX2 (5′-TTTCCTCCTGGCAGCTTAGA-3′ and 5′-GCTGGGAGATGAAACCAAAG-3′), CMA1 (5′-GGCTCCAAGGGTGACTGTTA-3′ and 5′-CCCCACTTTCCCGTTTAACT-3′), and SCL25A21 (5′-AACTCCATGTCGTCCCAAAG-3′ and 5′-CAAAATCGTTTGTTCTTTGCC-3′). Transcript-specific primers were used for DTX2 (5′-CAGGCATGACGAGTGTTCTG-3′ and 5′-CACAGCTAGGGACCCGAT-3′) and CMA1 (5′-CCCTGCTGCTCTTTCTCTTG-3′ and 5′-ACACACCTGTTCTTCCCCAG-3′).

Table 1.

Correlation between Acceptor Genotypes and the Appearance of E and I Transcripts[Note]

|

Observations for Genotype |

|||||||

| Homozygous NAGNAG |

Heterozygous |

Homozygous Non-NAGNAG |

|||||

| dbSNP ID | Gene Symbol | No. of Probands | cDNA Transcripts | No. of Probands | cDNA Transcripts | No. of Probands | cDNA Transcript |

| rs2245425 | TOR1AIP1a | 3 | E+I | 6 | E+I | 2 | I |

| rs2275992 | ZFP91a | 1 | E+I | 7 | E+I | 4 | E |

| rs1558876 | KIAA1001 | 0 | … | 6 | E+I | 6 | E |

| rs2290647 | KIAA1533 | 0 | … | 4 | E+I | 8 | E |

| rs4590242 | GABRR1 | 11 | E+I | 1 | E+I | 0 | … |

| rs1152522 | C14orf105 | 0 | … | 0 | … | 12 | I |

Note.— E+I indicates presence of both E and I transcripts; E indicates only E transcripts; I indicates only I transcripts.

See also figure 2.

Results

SNPs in NAGNAG Acceptors Influence Alternative Splicing

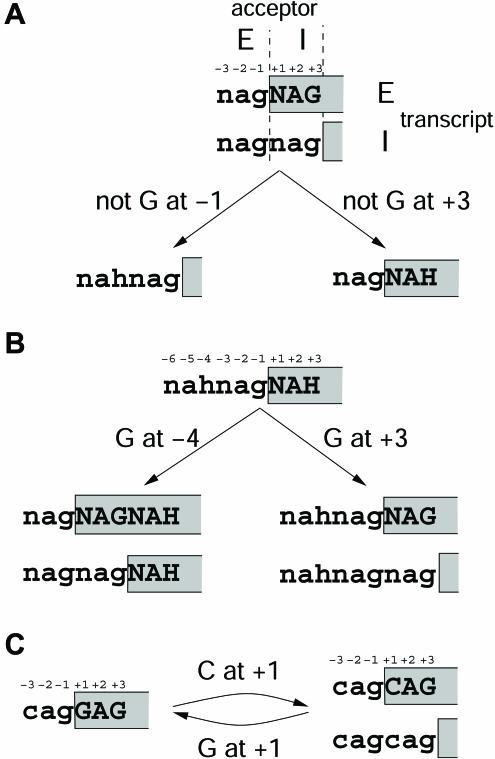

We extracted from the UCSC Human Genome Browser (hg17, May 2004) all annotated SNPs that are located within the last 6 nt of an intron or within the first 3 nt of an exon, given intron-exon boundaries from RefSeq transcripts. From these SNPs, we selected those that affect a NAGNAG acceptor. With respect to the human reference genome sequence, the alternative SNP allele can create or destroy a NAGNAG acceptor by affecting one of both AG alleles (fig. 1A and 1B). Since the nucleotide upstream of any acceptor AG is usually C or T (Stamm et al. 2000) and a change at this position is likely to alter alternative splicing at a tandem acceptor, we also considered SNPs at the N positions in an existing tandem (fig. 1C). We found a total of 137 NAGNAG-affecting SNPs (table 2). Aware of the uncertainty about the true nature of SNPs in segmental duplications (Fredman et al. 2004; Taudien et al. 2004), we excluded seven (5%) of the variations from further analysis. Our precaution was justified by genotyping SNP rs1638152 in 12 whites; we consistently found both alleles and both transcripts (DTX2 [GenBank accession numbers DQ082728 and DQ082730]), which is a strong indication for paralogous sequence variants and/or multisite variations (combinatorial P=.0003). Since dbSNP entries sometimes are the result of sequencing errors, we manually examined the trace data (if available) and excluded a further nine SNPs (7%). Thus, we considered a total of 121 bona fide SNPs affecting NAGNAG acceptors.

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of how SNPs affect splicing at NAGNAG acceptors. A, SNP alleles at position −2, −1, +2, or +3 of a NAGNAG acceptor destroy this motif by affecting the E (left) or I (right) acceptor, thus preventing alternative splicing. B, SNP alleles at intron positions −5 and −4 can create a novel E acceptor (left) and, at exon positions +2 and +3, a novel I acceptor (right), thus yielding a NAGNAG motif. Acceptors at these alleles may allow alternative splicing, as indicated by the two transcripts (E transcript above; I transcript below). C, SNP alleles at position −3 or +1 of a NAGNAG acceptor can convert a plausible NAGNAG that allows alternative splicing (left) to an implausible one that allows only the expression of one transcript (right), or vice versa. Positions refer to a standard intron-exon boundary. H denotes A, C, or T; upper- and lowercase letters indicate exonic and intronic nucleotides, respectively; exonic nucleotides are boxed.

Table 2.

SNPs That Affect NAGNAG Acceptors[Note]

| SNP | Protein Impact of | |||||||||||||

| dbSNP IDa | Chromosome | Position | Heterozygosity | Gene Symbol | Gene Nameb | RefSeq | Exon | Nucleotide Patternc | Variationd | Positione | Intron Phasef | NAGNAG Splicingg | Coding SNPh | EST/mRNAi |

| rs2297988 | 10 | 99108372 | .456 | KIAA0690 | KIAA0690 | NM_015179 | 33 | AAGCAG|AAA→GAGCAG|AAA | N | 1 | 0 | Insert Q | … | … |

| rs4149853 | 1 | 238338449 | .044 | EXO1 | Exonuclease 1 | NM_130398 | 3 | CAGCAG|AAC→TAGCAG|AAC | N | 1 | 5′ UTR | … | … | … |

| rs2071558 | 12 | 52105734 | .255 | AMHR2 | Anti-Mullerian hormone receptor, type II | NM_020547 | 6 | CAGCAG|GTA→TAGCAG|GTA | N | 1 | 0 | Insert Q | … | … |

| rs16960071 | 15 | 45846061 | .055 | SEMA6D | Sema domain, transmembrane domain (TM), and cytoplasmic domain, (semaphorin) 6D | NM_020858 | 16 | ATGAAG|GCT→AAGAAG|GCT | AG | 2 | 2 | Insert R | … | … |

| rs9621415 | 22 | 30953580 | … | SLC5A4 | Solute carrier family 5 (low affinity glucose cotransporter), member 4 | NM_014227 | 9 | CGGCAG|GTC→CAGCAG|GTC | AG | 2 | 0 | Insert Q | … | … |

| rs12042060k | 1 | 182663302 | … | FIBL-6 | Hemicentin | NM_031935 | 12 | TTGCAG|AAC→TAGCAG|AAC | AG | 2 | 1 | Insert A | … | … |

| rs2287800 | 16 | 25136015 | … | AQP8 | Aquaporin 8 | NM_001169 | 2 | CGGCAG|ATA→CAGCAG|ATA | AG | 2 | 0 | Insert Q | … | 1:0 |

| rs1650232j | 10 | 81309218 | … | SFTPA2 | Surfactant, pulmonary-associated protein A2 | NM_006926 | 3 | CTGCAG|GAG→CAGCAG|GAG | AG | 2 | 5′ UTR | … | … | 16:0 |

| rs3997775j | 10 | 81361506 | … | SFTPA1 | Surfactant, pulmonary-associated protein A1 | NM_005411 | 3 | CTGCAG|GAG→CAGCAG|GAG | AG | 2 | 5′ UTR | … | … | 2:0 |

| rs2298847 | 16 | 55258795 | .196 | MT1G | Metallothionein 1G | NM_005950 | 2 | TAGCAG|GTG→TTGCAG|GTG | AG | 2 | 1 | Insert A | … | 59:0 |

| rs1622213j | 1 | 1506424 | … | ATAD3B | ATPase family, AAA domain containing 3B | NM_031921 | 9 | CGGCAG|GTC→CAGCAG|GTC | AG | 2 | 0 | Insert Q | … | 1:0 |

| rs4590242 | 6 | 89969928 | .441 | GABRR1 | Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptor, rho 1 | NM_002042 | 2 | TGGTAG|GCC→TAGTAG|GCC | AG | 2 | 2 | Insert S | … | 2:0 |

| rs2521612 | 17 | 39686270 | … | SLC4A1 | Solute carrier family 4, anion exchanger, member 1 (erythrocyte membrane protein band 3, Diego blood group) | NM_000342 | 17 | CCGTAG|GCT→CAGTAG|GCT | AG | 2 | 2 | Insert R | … | … |

| rs2271959 | 17 | 38978266 | … | ETV4 | ETS variant gene 4 (E1A enhancer binding protein, E1AF) | NM_001986 | 3 | TCGCAG|AAA→TAGCAG|AAA | AG | 2 | 0 | Insert Q | … | 3:0 |

| rs3020724 | 10 | 104580737 | … | CYP17A1 | Cytochrome P450, family 17, subfamily A, polypeptide 1 | NM_000102 | 8 | CTGCAG|AGC→CAGCAG|AGC | AG | 2 | 1 | Insert A | … | … |

| rs6285 | 4 | 46875357 | … | GABRB1 | Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) A receptor, beta 1 | NM_000812 | 3 | CGGCAG|GGC→CAGCAG|GGC | AG | 2 | 1 | Insert A | … | … |

| rs5248 | 14 | 24045654 | .242 | CMA1 | Chymase 1, mast cell | NM_001836 | 3 | CAACAG|GTC→CAGCAG|GTC | AG | 3 | 2 | Insert S | … | … |

| rs3025420 | 9 | 133551742 | … | DBH | Dopamine beta-hydroxylase (dopamine beta-monooxygenase) | NM_000787 | 11 | CACCAG|GTT→CAGCAG|GTT | AG | 3 | 2 | Insert S | … | … |

| rs11466221 | 2 | 70653703 | .021 | TGFA | Transforming growth factor, alpha | NM_003236 | 2 | CAACAG|GTA→CAGCAG|GTA | AG | 3 | 1 | Insert A | … | … |

| rs363209 | 16 | 65412967 | … | APPBP1 | Amyloid beta precursor protein binding protein 1, 59kDa | NM_003905 | 7 | AAACAG|CAC→AAGCAG|CAC | AG | 3 | 2 | Insert S | … | … |

| rs9644946 | 9 | 124765060 | .178 | GOLGA1 | Golgi autoantigen, golgin subfamily a, 1 | NM_002077 | 8 | AAATAG|GAG→AAGTAG|GAG | AG | 3 | 0 | Insert stop | … | … |

| rs2245425 | 1 | 176590101 | .464 | TOR1AIP1 | Torsin A interacting protein 1 | NM_015602 | 3 | TAGCAG|TGA→TAACAG|TGA | AG | 3 | 1 | Insert A | … | 13:0 |

| rs200925 | 10 | 38166650 | … | ZNF248 | Zinc finger protein 248 | NM_021045 | 5 | TAACAG|GGT→TAGCAG|GGT | AG | 3 | 1 | Insert A | … | … |

| rs1438073 | 2 | 182954651 | … | PDE1A | Phosphodiesterase 1A, calmodulin-dependent | NM_001003683 | 3 | AAATAG|ACT→AAGTAG|ACT | AG | 3 | 2 | Insert R | … | … |

| rs13251099 | 8 | 12853939 | … | FLJ36980 | NA | NM_182598 | 2 | AAATAG|GTC→AAGTAG|GTC | AG | 3 | 5′ UTR | … | … | … |

| rs1076555k | 1 | 152043527 | … | SCAMP3 | Secretory carrier membrane protein 3 | NM_005698 | 3 | CAACAG|CCA→CAGCAG|CCA | AG | 3 | 0 | Insert Q | … | … |

| rs2290609 | 3 | 3119508 | … | IL5RA | Interleukin 5 receptor, alpha | NM_000564 | 5 | CAACAG|TTT→CAGCAG|TTT | AG | 3 | 1 | I versus TV | … | … |

| rs3816280 | 18 | 9578855 | … | PPP4R1 | Protein phosphatase 4, regulatory subunit 1 | NM_005134 | 5 | CAATAG|AAC→CAGTAG|AAC | AG | 3 | 1 | Insert V | … | … |

| rs8176139 | 17 | 38505426 | .011 | BRCA1 | Breast cancer 1, early onset | NM_007304 | 8 | GTTTAG|CAG→GTTGAG|CAG | N | 4 | 0 | Delete Q | … | 7:0 |

| rs6591368 | 11 | 68591544 | … | TPCN2 | Two pore segment channel 2 | NM_139075 | 8 | TCTTAG|CAG→TCTCAG|CAG | N | 4 | 0 | Delete Q | … | … |

| rs11042902 | 11 | 10612199 | … | MRVI1 | Murine retrovirus integration site 1 homolog | NM_006069 | 2 | AACCGG|CAG→AACCAG|CAG | AG | 5 | 2 | NR versus K | … | 1:1 |

| rs1152522 | 14 | 57018133 | .441 | C14orf105 | Chromosome 14 ORF 105 | NM_018168 | 4 | TCATAG|CAG→TCATGG|CAG | AG | 5 | 0 | Delete Q | … | 6:0 |

| rs2307130 | 1 | 100028610 | .475 | AGL | Amylo-1, 6-glucosidase, 4-alpha-glucanotransferase (glycogen debranching enzyme, glycogen storage disease type III) | NM_000644 | 2 | CTCTAG|AAG→CTCTGG|AAG | AG | 5 | 5′ UTR | … | … | … |

| rs9463545 | 6 | 49927803 | … | CRISP1 | Cysteine-rich secretory protein 1 | NM_001131 | 3 | TAACAG|AAG→TAACCG|AAG | AG | 5 | 0 | Delete K | … | … |

| rs11567804 | 12 | 8104059 | .109 | C3AR1 | Complement component 3a receptor 1 | NM_004054 | 2 | TTGCAG|AAG→TTGCAA|AAG | AG | 6 | 5′ UTR | … | … | … |

| rs13228988 | 7 | 69674388 | … | AUTS2 | Autism susceptibility candidate 2 | NM_015570 | 8 | CGATAG|CAG→CGATAA|CAG | AG | 6 | 2 | Delete S | … | 2:0 |

| rs479984 | 8 | 109039673 | … | MGC35555 | NA | NM_178565 | 5 | TACTAG|AAG→TACTAA|AAG | AG | 6 | 1 | Delete E | … | … |

| rs1044833 | 12 | 30754672 | … | C1QDC1 | C1q domain containing 1 | NM_001002259 | 18 | AAACAG|CAG→AAACAT|CAG | AG | 6 | 1 | Delete A | … | … |

| rs2243187 | 1 | 203402743 | .041 | IL19 | Interleukin 19 | NM_153758 | 5 | TCACAG|CAG→TCACAA|CAG | AG | 6 | 0 | Delete Q | … | … |

| rs1833783k | 19 | 54161349 | … | FTL | Ferritin, light polypeptide | NM_000146 | 3 | ATATAG|AAG→ATATAC|AAG | AG | 6 | 0 | Delete K | … | 11:0 |

| rs12974798 | 19 | 7532374 | … | NTE | Neuropathy target esterase | NM_006702 | 35 | TCGCAG|GAG→TCGCAG|AAG | N | 7 | 0 | Delete K | E→K | … |

| rs17173698 | 10 | 89458933 | .011 | PAPSS2 | 3′-Phosphoadenosine 5′-phosphosulfate synthase 2 | NM_004670 | 2 | TTATAG|GAG→TTATAG|AAG | N | 7 | 0 | Delete K | E→K | … |

| rs2261015j | 7 | 66007678 | .448 | RSAFD1 | Radical S-adenosyl methionine and flavodoxin domains 1 | NM_018264 | 12 | CTCCAG|GAG→CTCCAG|TAG | N | 7 | 1 | Delete V | G→V | … |

| rs1804783 | 19 | 13186422 | … | CACNA1A | Calcium channel, voltage-dependent, P/Q type, alpha 1A subunit | NM_023035 | 39 | TTGCAG|GAG→TTGCAG|TAG | N | 7 | 1 | Delete V | G→V | … |

| rs3842776 | 22 | 42906589 | … | PARVG | Parvin, gamma | NM_022141 | 4 | TTCCAG|GAG→TTCCAG|CAG | N | 7 | 1 | Delete A | G→A | … |

| rs879022 | 2 | 79276118 | … | REGL | Regenerating islet-derived-like, pancreatic stone protein-like, pancreatic thread protein-like (rat) | NM_006508 | 3 | GGACAG|GAG→GGACAG|AAG | N | 7 | 1 | Delete E | G→E | … |

| rs12944821 | 17 | 33030504 | … | AP1GBP1 | AP1 gamma subunit binding protein 1 | NM_007247 | 3 | TTTCAG|CAG→TTTCAG|GAG | N | 7 | 1 | Delete G | A→G | 5:0 |

| rs3751353 | 13 | 23793134 | .083 | MGC48915 | NA | NM_178540 | 4 | ATTTAG|GAG→ATTTAG|CAG | N | 7 | 1 | Delete A | G→A | … |

| rs4565430k | 8 | 97376502 | … | PTDSS1 | Phosphatidylserine synthase 1 | NM_014754 | 5 | AAATAG|GAG→AAATAG|CAG | N | 7 | 0 | Delete Q | E→Q | … |

| rs2409496 | 21 | 33825733 | … | GART | Phosphoribosylglycinamide formyltransferase, phosphoribosylglycinamide synthetase, phosphoribosylaminoimidazole synthetase | NM_175085 | 6 | AATCAG|GAG→AATCAG|CAG | N | 7 | 0 | Delete Q | E→Q | … |

| rs1638152j | 7 | 75774409 | .476 | DTX2 | Deltex homolog 2 (Drosophila) | NM_020892 | 8 | TTCTAG|GAG→TTCTAG|AAG | N | 7 | 1 | Delete E | G→E | … |

| rs3775296 | 4 | 187372916 | .268 | TLR3 | Toll-like receptor 3 | NM_003265 | 2 | CTACAG|CAG→CTACAG|AAG | N | 7 | 5′ UTR | … | … | … |

| rs1127307 | 19 | 14450378 | … | RGS19IP1 | Regulator of G-protein signaling 19 interacting protein 1 | NM_202494 | 6 | CAATAG|CGG→CAATAG|CAG | AG | 8 | 1 | Delete A | … | 8:0 |

| rs1071716 | 9 | 35675135 | … | TPM2 | Tropomyosin 2 (beta) | NM_213674 | 6 | CCCCAG|CCG→CCCCAG|CAG | AG | 8 | 2 | Delete S | … | … |

| rs11660370 | 18 | 19028411 | … | CABLES1 | Cdk5 and Abl enzyme substrate 1 | NM_138375 | 3 | TTTCAG|ATG→TTTCAG|AAG | AG | 8 | 2 | Delete R | C→S | … |

| rs2010657 | 22 | 23328476 | … | GGT1 | Gamma-glutamyltransferase 1 | NM_013421 | 2 | CCCCAG|CGG→CCCCAG|CAG | AG | 8 | 5′ UTR | … | … | … |

| rs2275992 | 11 | 58135000 | .29 | ZFP91 | Zinc finger protein 91 homolog (mouse) | NM_170768 | 5 | TTTTAG|TAG→TTTTAG|TGG | AG | 8 | 2 | Delete S | S→G | 7:0 |

| rs10914468 | 1 | 31833299 | .497 | COL16A1 | Collagen, type XVI, alpha 1 | NM_001856 | 5 | CTCCAG|AAG→CTCCAG|ACG | AG | 8 | 2 | Delete R | … | … |

| rs4434604 | 8 | 67227167 | … | TRIM55 | Tripartite motif-containing 55 | NM_033058 | 8 | TACCAG|AAG→TACCAG|AGG | AG | 8 | 1 | Delete E | … | … |

| rs751517 | 22 | 36345477 | … | GGA1 | Golgi associated, gamma adaptin ear containing, ARF binding protein 1 | NM_013365 | 10 | TTCCAG|CGG→TTCCAG|CAG | AG | 8 | 1 | Delete A | … | … |

| rs11661706 | 18 | 5409875 | … | EPB41L3 | Erythrocyte membrane protein band 4.1-like 3 | NM_012307 | 12 | CTGCAG|AGG→CTGCAG|AAG | AG | 8 | 1 | Delete E | … | … |

| rs2273431 | 14 | 51566157 | .178 | NID2 | Nidogen 2 (osteonidogen) | NM_007361 | 10 | ATGCAG|AGG→ATGCAG|AAG | AG | 8 | 1 | Delete E | … | … |

| rs3746373 | 20 | 61409288 | .113 | KIAA1510 | NA | NM_020882 | 6 | CCCCAG|CCG→CCCCAG|CAG | AG | 8 | 1 | Delete A | … | … |

| rs7862221 | 9 | 132811775 | … | TSC1 | Tuberous sclerosis 1 | NM_000368 | 14 | CTTCAG|AAG→CTTCAG|AGG | AG | 8 | 1 | Delete E | … | … |

| rs2290647 | 19 | 40198569 | .371 | KIAA1533 | KIAA1533 | NM_020895 | 11 | CTCCAG|CGG→CTCCAG|CAG | AG | 8 | 1 | Delete A | … | 35:0 |

| rs11553436 | 22 | 41232623 | … | SERHL | Serine hydrolase-like | NM_170694 | 11 | CTCCAG|CGG→CTCCAG|CAG | AG | 8 | 3′ UTR | … | … | … |

| rs12760076 | 1 | 44354572 | … | DMAP1 | DNA methyltransferase 1 associated protein 1 | NM_019100 | 8 | TTGCAG|ATG→TTGCAG|AAG | AG | 8 | 0 | Delete K | M→K | … |

| rs2243603 | 20 | 1494911 | .364 | SIRPB1 | Signal-regulatory protein beta 1 | NM_006065 | 5 | TTCCAG|AAG→TTCCAG|AAC | AG | 9 | 1 | Delete E | A→P | … |

| rs3765018 | 1 | 54880319 | .235 | FLJ46354 | NA | NM_198547 | 23 | TCCCAG|AAG→TCCCAG|AAA | AG | 9 | 3′ UTR | … | … | 1:0 |

| rs1558876 | 17 | 63876286 | .455 | KIAA1001 | NA | NM_014960 | 6 | TTTCAG|CAC→TTTCAG|CAG | AG | 9 | 2 | Delete S | T→S | 2:0 |

| rs9611697k | 22 | 40713170 | … | SEPT3 | Septin 3 | NM_145733 | 8 | GTGCAG|CAG→GTGCAG|CAC | AG | 9 | 0 | Delete Q | Q→H | … |

| rs3014960 | 13 | 44975382 | .221 | COG3 | Component of oligomeric golgi complex 3 | NM_031431 | 14 | ATACAG|CAG→ATACAG|CAA | AG | 9 | 0 | Delete Q | … | … |

| rs11597439 | 10 | 104174943 | … | CUEDC2 | CUE domain containing 2 | NM_024040 | 2 | CTTCAG|AAG→CTTCAG|AAC | AG | 9 | 5′ UTR | … | … | 2:0 |

| rs11574323 | 8 | 31101968 | .011 | WRN | Werner syndrome | NM_000553 | 23 | GGGTAG|AAT→GGGTAG|AAG | AG | 9 | 2 | QS versus H | I→S | … |

| rs2425068 | 20 | 33678137 | … | CPNE1 | Copine I | NM_152927 | 16 | CCCCAG|CAA→CCCCAG|CAG | AG | 9 | 0 | Delete Q | … | 7:0 |

| rs3738833 | 1 | 36528845 | … | LSM10 | LSM10, U7 small nuclear RNA associated | NM_032881 | 2 | CCACAG|CAA→CCACAG|CAG | AG | 9 | 5′ UTR | … | … | … |

| rs17105087 | 14 | 36250436 | .378 | SLC25A21 | Solute carrier family 25 (mitochondrial oxodicarboxylate carrier), member 21 | NM_030631 | 7 | CTGCAG|CAA→CTGCAG|CAG | AG | 9 | 0 | Delete Q | … | … |

| rs9606756 | 22 | 29331414 | .131 | TCN2 | Transcobalamin II, macrocytic anemia | NM_000355 | 2 | TCTAAG|AAA→TCTAAG|AAG | AG | 9 | 1 | Delete E | I→V | 2:0 |

| rs2292402 | 3 | 142435751 | .299 | ACPL2 | Acid phosphatase-like 2 | NM_152282 | 2 | GAGCAG|TGA→GTGCAG|TGA | AG | 2 | 5′ UTR | … | … | … |

| rs6670368k | 1 | 89138996 | … | KAT3 | Kynurenine aminotransferase III | NM_001008661 | 8 | GTGTAG|GTG→GAGTAG|GTG | AG | 2 | 0 | Insert stop | … | … |

| rs10152092 | 14 | 23103212 | … | AP1G2 | Adaptor-related protein complex 1, gamma 2 subunit | NM_003917 | 11 | GACCAG|GTA→GAGCAG|GTA | AG | 3 | 2 | Insert S | … | … |

| rs12905385 | 15 | 40808855 | .262 | CDAN1 | Congenital dyserythropoietic anemia, type I | NM_138477 | 18 | ATACAG|GAG→ATATAG|GAG | N | 4 | 1 | Delete G | … | … |

| rs2250205 | 20 | 33331338 | .389 | ITGB4BP | Integrin beta 4 binding protein | NM_181467 | 4 | TGACAG|GAG→TGATAG|GAG | N | 4 | 1 | Delete G | … | … |

| rs5703 | 1 | 71040104 | .068 | PTGER3 | Prostaglandin E receptor 3 (subtype EP3) | NM_198713 | 4 | TAATAG|GAG→TAACAG|GAG | N | 4 | 1 | RE versus K | … | … |

| rs9635649j | X | 169594 | … | GTPBP6 | GTP binding protein 6 (putative) | NM_012227 | 2 | TTTTAG|GAG→TTTCAG|GAG | N | 4 | 2 | Delete R | … | … |

| rs3087402 | 2 | 99510924 | .011 | REV1L | REV1-like (yeast) | NM_016316 | 7 | TTCTAG|GAG→TTCCAG|GAG | N | 4 | 1 | Delete G | … | … |

| rs762605 | 1 | 9032117 | … | SLC2A5 | Solute carrier family 2 (facilitated glucose/fructose transporter), member 5 | NM_003039 | 12 | CCGCAG|GAG→CCGTAG|GAG | N | 4 | 0 | Delete E | … | … |

| rs3765166 | 2 | 172519287 | .406 | SLC25A12 | Solute carrier family 25 (mitochondrial carrier, Aralar), member 12 | NM_003705 | 6 | TCACAG|GAG→TCATAG|GAG | N | 4 | 0 | Delete E | … | … |

| rs2174769 | 1 | 37675452 | .378 | SNIP1 | Smad nuclear interacting protein | NM_024700 | 3 | TTTTAG|GAG→TTTCAG|GAG | N | 4 | 0 | Delete E | … | … |

| rs9866111 | 3 | 101857430 | .469 | GPR128 | G protein-coupled receptor 128 | NM_032787 | 13 | ACATAG|GAG→ACACAG|GAG | N | 4 | 1 | Delete G | … | … |

| rs10169344 | 2 | 113048652 | .341 | POLR1B | Polymerase (RNA) I polypeptide B, 128 kDa | NM_019014 | 15 | TCCTAG|GAG→TCCCAG|GAG | N | 4 | 2 | KS versus N | … | … |

| rs4933199 | 10 | 92621451 | … | RPP30 | Ribonuclease P/MRP 30 kDa subunit | NM_006413 | 2 | TTATAG|GAG→TTACAG|GAG | N | 4 | 5′ UTR | … | … | … |

| rs3821010 | 2 | 178508162 | .375 | PDE11A | Phosphodiesterase 11A | NM_016953 | 8 | CCATAG|GAG→CCACAG|GAG | N | 4 | 1 | Delete G | … | … |

| rs1046617 | 20 | 61844130 | … | SLC2A4RG | SLC2A4 regulator | NM_020062 | 6 | CCGCAG|GAG→CCGGAG|GAG | N | 4 | 2 | Delete R | … | … |

| rs7279250 | 21 | 45539120 | … | C21orf86 | Chromosome 21 ORF 86 | NM_153454 | 2 | GACGAG|GAG→GACGTG|GAG | AG | 5 | 5′ UTR | … | … | … |

| rs12883949 | 14 | 102465744 | … | AMN | Amnionless homolog (mouse) | NM_030943 | 8 | CCGCAG|GAG→CCGCAA|GAG | AG | 6 | 1 | Delete G | … | … |

| rs2306949 | 4 | 71520483 | … | MUC7 | Mucin 7, salivary | NM_152291 | 2 | TCCCAG|GAG→TCCCAA|GAG | AG | 6 | 5′ UTR | … | … | 1:0 |

| rs10981449k | 9 | 112415891 | … | KIAA1958 | KIAA1958 | NM_133465 | 2 | CTTTAG|GAG→CTTTAA|GAG | AG | 6 | 5′ UTR | … | … | … |

| rs11591994 | 10 | 98072403 | … | DNTT | Deoxynucleotidyltransferase, terminal | NM_004088 | 5 | CATTAG|GAG→CATTAC|GAG | AG | 6 | 0 | Delete E | … | … |

| rs3966262 | 22 | 23330878 | … | GGT1 | Gamma-glutamyltransferase 1 | NM_013421 | 5 | CTTCAG|GAG→CTTCAA|GAG | AG | 6 | 5′ UTR | … | … | … |

| rs6111953k | 20 | 18355804 | … | C20orf12 | Chromosome 20 ORF 12 | NM_018152 | 9 | GTTAAG|GAG→GTTAAA|GAG | AG | 6 | 0 | Delete E | … | … |

| rs11752742 | 6 | 64049085 | … | GLULD1 | Glutamate-ammonia ligase (glutamine synthase) domain containing 1 | NM_016571 | 4 | CTTTAG|GAG→CTTTAA|GAG | AG | 6 | 0 | Delete E | … | … |

| rs193227 | 15 | 32421602 | … | NOLA3 | Nucleolar protein family A, member 3 (H/ACA small nucleolar RNPs) | NM_018648 | 2 | GAGCAG|AAA→GAGCAA|AAA | AG | 6 | 0 | Insert Q | … | … |

| rs1509545 | 15 | 79206987 | … | C15orf26 | Chromosome 15 ORF 26 | NM_173528 | 2 | ATTAAG|GTG→ATTAAG|GAG | AG | 8 | 5′ UTR | … | … | … |

| rs1140420 | 15 | 61804764 | … | HERC1 | HECT (homologous to the E6-AP (UBE3A) carboxyl terminus) domain and RCC1 (CHC1)-like domain (RLD) 1 | NM_003922 | 18 | CTTTAG|GAG→CTTTAG|GGG | AG | 8 | 1 | Delete G | … | … |

| rs2272238 | 12 | 32751569 | .017 | DNM1L | Dynamin 1-like | NM_012062 | 3 | TTCCAG|GGG→TTCCAG|GAG | AG | 8 | 1 | Delete G | … | … |

| rs11781386 | 8 | 141484978 | … | T1 | NA | NM_031466 | 6 | TTGCAG|GTG→TTGCAG|GAG | AG | 8 | 1 | Delete G | … | … |

| rs1130329 | 7 | 4885795 | .478 | LOC389458 | NA | NM_203393 | 3 | CCCCAG|GAG→CCCCAG|GCG | AG | 8 | 0 | Delete E | E→A | … |

| rs13405053 | 2 | 54274242 | … | ACYP2 | Acylphosphatase 2, muscle type | NM_138448 | 2 | ATACAG|GTG→ATACAG|GAG | AG | 8 | 1 | Delete G | … | … |

| rs9272863 | 6 | 32718708 | … | HLA-DQA1 | Major histocompatibility complex, class II, DQ alpha 1 | NM_002122 | 5 | TTGCAG|GTG→TTGCAG|GAG | AG | 8 | 3′ UTR | … | … | … |

| rs4049844 | 22 | 23340850 | … | GGT1 | Gamma-glutamyltransferase 1 | NM_005265 | 6 | CCCCAG|GGG→CCCCAG|GAG | AG | 8 | 1 | Delete G | … | … |

| rs4024419 | 7 | 151373558 | … | MLL3 | Myeloid/lymphoid or mixed-lineage leukemia 3 | NM_170606 | 15 | TCCTAG|GGG→TCCTAG|GAG | AG | 8 | 0 | Delete E | G→E | … |

| rs2236215 | 1 | 15637721 | .463 | KIAA0962 | NA | NM_015291 | 12 | TTTTAG|GAG→TTTTAG|GCG | AG | 8 | 2 | Delete R | … | … |

| rs5744948 | 12 | 131829664 | .012 | POLE | Polymerase (DNA directed), epsilon | NM_006231 | 37 | ACCCAG|GAG→ACCCAG|GCG | AG | 8 | 0 | Delete E | E→A | … |

| rs4994616 | 1 | 148360461 | … | TUFT1 | Tuftelin 1 | NM_020127 | 9 | ACCCAG|GAG→ACCCAG|GCG | AG | 8 | 0 | Delete E | E→A | … |

| rs1136881j | 6_hla_hap1 | 61968 | … | HLA-DRB3 | Major histocompatibility complex, class II, DR beta 3 | NM_022555 | 4 | TCTCAG|GAG→TCTCAG|GTG | AG | 8 | 1 | RA versus T | R→S | … |

| rs3209388 | 9 | 19366385 | … | RPS6 | Ribosomal protein S6 | NM_001010 | 6 | GTTTAG|GAG→GTTTAG|GGG | AG | 8 | 0 | Delete E | E→G | … |

| rs12816732 | 12 | 128219086 | … | KIAA1944 | NA | NM_133448 | 5 | TTCCAG|GAG→TTCCAG|GAA | AG | 9 | 0 | Delete E | … | … |

| rs17036879 | 3 | 12535560 | .055 | TSEN2 | tRNA splicing endonuclease 2 homolog (SEN2, S. cerevisiae) | NM_025265 | 8 | CTTTAG|GAG→CTTTAG|GAA | AG | 9 | 0 | Delete E | … | … |

| rs1132591 | 19 | 59514796 | … | LILRA5 | Leukocyte immunoglobulin-like receptor, subfamily A (with TM domain), member 5 | NM_181879 | 5 | TCCTAG|GAT→TCCTAG|GAG | AG | 9 | 1 | Delete G | F→V | … |

| rs7182782 | 15 | 61729175 | … | HERC1 | HECT (homologous to the E6-AP (UBE3A) carboxyl terminus) domain and RCC1 (CHC1)-like domain (RLD) 1 | NM_003922 | 54 | TTTTAG|GAG→TTTTAG|GAA | AG | 9 | 1 | Delete G | G→R | … |

| rs3734334 | 6 | 36898850 | .012 | CPNE5 | Copine V | NM_020939 | 2 | TTTCAG|GAA→TTTCAG|GAG | AG | 9 | 2 | Delete R | N→S | … |

| rs3816208 | 8 | 97683801 | .115 | SDC2 | Syndecan 2 (heparan sulfate proteoglycan 1, cell surface-associated, fibroglycan) | NM_002998 | 3 | TTCCAG|GAG→TTCCAG|GAA | AG | 9 | 1 | Delete G | A→T | … |

| rs4150167 | 16 | 82771185 | .026 | TAF1C | TATA box binding protein (TBP)-associated factor, RNA polymerase I, C, 110 kDa | NM_139353 | 14 | CAGGAG|AAG→CAGGAG|AAA | AG | 9 | 1 | Delete G / Delete GE | G→R | … |

| rs6836935 | 4 | 187918076 | … | FAT | FAT tumor suppressor homolog 1 (Drosophila) | NM_005245 | 11 | TTCCAG|GAA→TTCCAG|GAG | AG | 9 | 1 | Delete G | N→D | … |

| rs2843414 | 1 | 199126353 | … | PPP1R12B | Protein phosphatase 1, regulatory (inhibitor) subunit 12B | NM_002481 | 4 | CTGTAG|GAG→CTGTAG|GAA | AG | 9 | 1 | Delete G | V→I | … |

| rs9474034 | 6 | 51605478 | … | PKHD1 | Polycystic kidney and hepatic disease 1 (autosomal recessive) | NM_138694 | 65 | CCACAG|GAG→CCACAG|GAA | AG | 9 | 1 | Delete G | V→I | … |

| rs1040310 | 6 | 32115304 | … | CYP21A2 | Cytochrome P450, family 21, subfamily A, polypeptide 2 | NM_000500 | 5 | TGGCAG|GAC→TGGCAG|GAG | AG | 9 | 0 | Delete E | D→E | … |

| rs2854741 | 22 | 40861902 | .246 | CYP2D7P1 | Cytochrome P450, family 2, subfamily D, polypeptide 7 pseudogene 1 | NM_001002910 | 7 | ACACAG|GAC→ACACAG|GAG | AG | 9 | 2 | Delete R | T→R | … |

| rs2156634 | 11 | 120281211 | .191 | GRIK4 | Glutamate receptor, ionotropic, kainate 4 | NM_014619 | 11 | CTGCAG|GAG→CTGCAG|GAA | AG | 9 | 0 | Delete E | … | … |

| rs2228112 | 5 | 127497758 | .449 | SLC12A2 | Solute carrier family 12 (sodium/potassium/chloride transporters), member 2 | NM_001046 | 6 | TTCTAG|GAA→TTCTAG|GAG | AG | 9 | 0 | Delete E | … | … |

| rs1152888 | 12 | 64891495 | .327 | IRAK3 | Interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase 3 | NM_007199 | 5 | CCTAAG|GAA→CCTAAG|GAG | AG | 9 | 1 | Delete G | I→V | … |

| rs4822258 | 22 | 41780029 | .242 | TTLL1 | Tubulin tyrosine ligase-like family, member 1 | NM_001008572 | 9 | CACCAG|GAG→CACCAG|GAA | AG | 9 | 0 | Delete E | … | … |

| rs1654551 | 19 | 56104480 | … | KLK4 | Kallikrein 4 (prostase, enamel matrix, prostate) | NM_004917 | 2 | CCTCAG|GAT→CCTCAG|GAG | AG | 9 | 1 | Delete G | S→A | … |

| rs7344530k | 20 | 20119988 | … | C20orf26 | Chromosome 20 ORF 26 | NM_015585 | 15 | TTTCAG|GAT→TTTCAG|GAG | AG | 9 | 0 | Delete E | D→E | … |

| rs3179757 | 19 | 18190846 | … | PDE4C | Phosphodiesterase 4C, cAMP-specific (phosphodiesterase E1 dunce homolog, Drosophila) | NM_000923 | 9 | TCTTAG|GAG→TCTTAG|GAA | AG | 9 | 0 | Delete E | … | … |

| rs3815354 | 17 | 9763745 | … | GAS7 | Growth arrest-specific 7 | NM_201433 | 12 | TTCCAG|GAG→TTCCAG|GAC | AG | 9 | 1 | Delete G | D→H | … |

Note.— Data are from UCSC Human Genome Browser SNP source download January 9, 2005).

Plausible NAGNAG acceptors are shown in bold italics; implausible NAGNAG acceptors are shown in italics.

NA = no approved gene name.

9-nt acceptor context (−6…+3); reference genome sequence is on the left, and alternative SNP allele is on the right.

AG = one of both AG affected; N = one N in the NAGNAG pattern is affected.

Position of the SNP in the 9-nt acceptor context (from 1 = intron position −6 to 9 = exon position +3).

Intron phase of the intron or 5′/3′ UTR.

Impact of alternative splicing on the protein sequence.

aa change of missense SNPs.

Number of ESTs/mRNAs confirming the NAGNAG splice event alternative to the given RefSeq.

UCSC Human Genome Browser paralog warning; therefore, excluded from further analysis and table 6.

dbSNP entry is based on a sequencing error; therefore, excluded from further analysis and table 6.

Searching dbEST (December 2004), we obtained confirmation for alternative splicing at 16% (19 of 121) of these tandem acceptors. However, this percentage must be considered a lower bound. In addition to the general limitations of an EST-based evaluation of alternative splicing (insufficient EST coverage, especially for tandem acceptors that are spliced in a tissue-specific manner), the allele frequencies of the NAGNAG alleles and populational biases in EST sampling introduce further constrictions. Noteworthy, 18 (95%) of the 19 confirmed tandem acceptors match the consensus HAGHAG (H denotes A, C, or T). Thus, 26% of the 68 polymorphic HAGHAGs are EST confirmed, whereas only 1.9% of the 53 acceptors carrying G at one or both variable positions of the NAGNAG motif are EST supported. This is in line with our previous genomewide analysis, in which 31% of the HAGHAGs and only 1.7% of the remaining NAGNAGs were found to be experimentally confirmed (see table 1 of Hiller et al. [2004]). On the basis of these differences in the degree of confirmation by mRNA and EST data, we propose to subdivide all tandem acceptors into “plausible” (HAGHAG) and “implausible” (GAGHAG, HAGGAG, or GAGGAG) acceptors. Further support for this classification comes from the genomewide observation that all plausible NAGNAGs have the same bias toward intron phase 1, as described elsewhere (Hiller et al. 2004) for experimentally confirmed NAGNAGs, whereas the introns with implausible tandem acceptors are not biased toward phase 1 (table 3).

Table 3.

Phase Distribution of Human Introns and NAGNAG Acceptors[Note]

Accordingly, 68 (56%) of the 121 SNPs affect a plausible NAGNAG. However, four of those convert a plausible into another plausible NAGNAG, which has presumably no drastic consequence for NAGNAG splicing, even though we cannot exclude the possibility of changes in the ratio of E to I transcripts or of changes in tissue specificity. Thus, we consider the remaining 64 (53%) SNPs as relevant for NAGNAG splicing (table 4).

Table 4.

SNPs Affecting Plausible NAGNAG Acceptors[Note]

| dbSNP ID | Gene Symbol | RefSeq ID | Exon | Nucleotide Patterna | mRNA/ESTb | Intron Phasec | Protein Impactd | Chimpanzeee | Human versus Chimpanzeef |

| rs2307130 | AGL | NM_000644 | 2 | CTCTAG|AAG→CTCTGG|AAG | … | 5′ UTR | TAGAAG | Loss | |

| rs12944821 | AP1GBP1 | NM_007247 | 3 | TTTCAG|CAG→TTTCAG|GAG | 12:5 | 1 | Delete G | CAGCAG | Loss |

| rs363209 | APPBP1 | NM_003905 | 7 | AAACAG|CAC→AAGCAG|CAC | 2 | Insert S | AAACAG | Gain | |

| rs2287800 | AQP8 | NM_001169 | 2 | CGGCAG|ATA→CAGCAG|ATA | 1:14 | 0 | Insert Q | CGGCAG | Gain |

| rs13228988 | AUTS2 | NM_015570 | 8 | CGATAG|CAG→CGATAA|CAG | 4:2 | 2 | Delete S | TAGCAG | Loss |

| rs8176139 | BRCA1h | NM_007304 | 8 | GTTTAG|CAG→GTTGAG|CAG | 26:7 | 0 | Delete Q | TAGCAG | Loss |

| rs1152522 | C14orf105 | NM_018168 | 4 | TCATAG|CAG→TCATGG|CAG | 3:6 | 0 | Delete Q | TAGCAG | Loss |

| rs1044833 | C1QDC1h | NM_001002259 | 18 | AAACAG|CAG→AAACAT|CAG | 1 | Delete A | CAGCAG | Loss | |

| rs11567804 | C3AR1 | NM_004054 | 2 | TTGCAG|AAG→TTGCAA|AAG | … | 5′ UTR | CAGAAG | Loss | |

| rs11660370 | CABLES1 | NM_138375 | 3 | TTTCAG|ATG→TTTCAG|AAG | 2 | Delete R | CAGATG | Gain | |

| rs1804783 | CACNA1A | NM_023035 | 39 | TTGCAG|GAG→TTGCAG|TAG |

1 | Delete V | CAGGAG | Gain | |

| rs5248 | CMA1 | NM_001836 | 3 | CAACAG|GTC→CAGCAG|GTC | 15:21g | 2 | Insert S | CAACAG | Gain |

| rs3014960 | COG3 | NM_031431 | 14 | ATACAG|CAG→ATACAG|CAA | 0 | Delete Q | CAGCAA | Gain | |

| rs10914468 | COL16A1 | NM_001856 | 5 | CTCCAG|AAG→CTCCAG|ACG | 2 | Delete R | CAGACG | Gain | |

| rs2425068 | CPNE1 | NM_152927 | 16 | CCCCAG|CAA→CCCCAG|CAG | 79:7 | 0 | Delete Q | CAGCAA | Gain |

| rs9463545 | CRISP1 | NM_001131 | 3 | TAACAG|AAG→TAACCG|AAG | 0 | Delete K | CAGAAG | Loss | |

| rs11597439 | CUEDC2 | NM_024040 | 2 | CTTCAG|AAG→CTTCAG|AAC | 49:2 | … | 5′ UTR | CAGAAG | Loss |

| rs3020724 | CYP17A1 | NM_000102 | 8 | CTGCAG|AGC→CAGCAG|AGC | 1 | Insert A | CTGCAG | Gain | |

| rs3025420 | DBH | NM_000787 | 11 | CACCAG|GTT→CAGCAG|GTT | 2 | Insert S | CACCAG | Gain | |

| rs12760076 | DMAP1 | NM_019100 | 8 | TTGCAG|ATG→TTGCAG|AAG | 0 | Delete K | CAGATG | Gain | |

| rs11661706 | EPB41L3 | NM_012307 | 12 | CTGCAG|AGG→CTGCAG|AAG | 1 | Delete E | CAGAGG | Gain | |

| rs2271959 | ETV4 | NM_001986 | 3 | TCGCAG|AAA→TAGCAG|AAA | 3:17 | 0 | Insert Q | TCGCAG | Gain |

| rs13251099 | FLJ36980 | NM_182598 | 2 | AAATAG|GTC→AAGTAG|GTC | … | 5′ UTR | AAATAG | Gain | |

| rs3765018 | FLJ46354 | NM_198547 | 23 | TCCCAG|AAG→TCCCAG|AAA | 11:1 | … | 3′ UTR | CAGAAA | Gain |

| rs6285 | GABRB1 | NM_000812 | 3 | CGGCAG|GGC→CAGCAG|GGC | 1 | Insert A | NA | NA | |

| rs4590242 | GABRR1 | NM_002042 | 2 | TGGTAG|GCC→TAGTAG|GCC | 2:2 | 2 | Insert S | TAGTAG | Loss |

| rs2409496 | GART | NM_175085 | 6 | AATCAG|GAG→AATCAG|CAG | 0 | Delete Q | CAGGAG | Gain | |

| rs751517 | GGA1 | NM_013365 | 10 | TTCCAG|CGG→TTCCAG|CAG | 1 | Delete A | NA | NA | |

| rs2010657 | GGT1h | NM_013421 | 2 | CCCCAG|CGG→CCCCAG|CAG | … | 5′ UTR | CAGCGG | Gain | |

| rs9644946 | GOLGA1 | NM_002077 | 8 | AAATAG|GAG→AAGTAG|GAG | 0 | Insert stop | AAATAG | Gain | |

| rs2243187 | IL19 | NM_153758 | 5 | TCACAG|CAG→TCACAA|CAG | 0 | Delete Q | CAGCAG | Loss | |

| rs2290609 | IL5RA | NM_000564 | 5 | CAACAG|TTT→CAGCAG|TTT | 1 | I versus TV | CAACAG | Gain | |

| rs2297988 | KIAA0690 | NM_015179 | 33 | AAGCAG|AAA→GAGCAG|AAA | 0 | Insert Q | GAGCAG | Gain | |

| rs1558876 | KIAA1001 | NM_014960 | 6 | TTTCAG|CAC→TTTCAG|CAG | 10:2 | 2 | Delete S | CAGCAG | Loss |

| rs3746373 | KIAA1510 | NM_020882 | 6 | CCCCAG|CCG→CCCCAG|CAG | 1 | Delete A | CAGCCG | Gain | |

| rs2290647 | KIAA1533 | NM_020895 | 11 | CTCCAG|CGG→CTCCAG|CAG | 34:35 | 1 | Delete A | CAGCGG | Gain |

| rs3738833 | LSM10 | NM_032881 | 2 | CCACAG|CAA→CCACAG|CAG | … | 5′ UTR | CAGCAA | Gain | |

| rs479984 | MGC35555 | NM_178565 | 5 | TACTAG|AAG→TACTAA|AAG | 1 | Delete E | TAGAAG | Loss | |

| rs3751353 | MGC48915 | NM_178540 | 4 | ATTTAG|GAG→ATTTAG|CAG | 1 | Delete A | TAGGAG | Gain | |

| rs11042902 | MRVI1 | NM_006069 | 2 | AACCGG|CAG→AACCAG|CAG | 2:2 | 2 | NR versus K | CAGCAG | Loss |

| rs2298847 | MT1G | NM_005950 | 2 | TAGCAG|GTG→TTGCAG|GTG | 59:14 | 1 | Insert A | TTGCAG | Gain |

| rs2273431 | NID2 | NM_007361 | 10 | ATGCAG|AGG→ATGCAG|AAG | 1 | Delete E | CAGAGG | Gain | |

| rs12974798 | NTE | NM_006702 | 35 | TCGCAG|GAG→TCGCAG|AAG | 0 | Delete K | CAGGAG | Gain | |

| rs17173698 | PAPSS2 | NM_004670 | 2 | TTATAG|GAG→TTATAG|AAG | 0 | Delete K | TAGGAG | Gain | |

| rs3842776 | PARVG | NM_022141 | 4 | TTCCAG|GAG→TTCCAG|CAG | 1 | Delete A | CAGGAG | Gain | |

| rs1438073 | PDE1A | NM_001003683 | 3 | AAATAG|ACT→AAGTAG|ACT | 2 | Insert R | AAATAG | Gain | |

| rs3816280 | PPP4R1 | NM_005134 | 5 | CAATAG|AAC→CAGTAG|AAC | 1 | Insert V | CAATAG | Gain | |

| rs879022 | REGL | NM_006508 | 3 | GGACAG|GAG→GGACAG|AAG | 1 | Delete E | CAGGAG | Gain | |

| rs1127307 | RGS19IP1 | NM_202494 | 6 | CAATAG|CGG→CAATAG|CAG | 87:8 | 1 | Delete A | NA | NA |

| rs16960071 | SEMA6D | NM_020858 | 16 | ATGAAG|GCT→AAGAAG|GCT | 2 | Insert R | ATGAAG | Gain | |

| rs11553436 | SERHL | NM_170694 | 11 | CTCCAG|CGG→CTCCAG|CAG | … | 3′ UTR | CAGCGG | Gain | |

| rs2243603 | SIRPB1 | NM_006065 | 5 | TTCCAG|AAG→TTCCAG|AAC | 1 | Delete E | CAGAAC | Gain | |

| rs17105087 | SLC25A21 | NM_030631 | 7 | CTGCAG|CAA→CTGCAG|CAG | 0 | Delete Q | CAGCAA | Gain | |

| rs2521612 | SLC4A1 | NM_000342 | 17 | CCGTAG|GCT→CAGTAG|GCT | 2 | Insert R | CCGTAG | Gain | |

| rs9621415 | SLC5A4 | NM_014227 | 9 | CGGCAG|GTC→CAGCAG|GTC | 0 | Insert Q | CGGCAG | Gain | |

| rs9606756 | TCN2 | NM_000355 | 2 | TCTAAG|AAA→TCTAAG|AAG | 62:2 | 1 | Delete E | AAGAAA | Gain |

| rs11466221 | TGFAh | NM_003236 | 2 | CAACAG|GTA→CAGCAG|GTA | 1 | Insert A | CAACAG | Gain | |

| rs2245425 | TOR1AIP1h | NM_015602 | 3 | TAGCAG|TGA→TAACAG|TGA | 13:41 | 1 | Insert A | TAGCAG | Loss |

| rs1071716 | TPM2 | NM_213674 | 6 | CCCCAG|CCG→CCCCAG|CAG | 2 | Delete S | CAGTCG | Gain | |

| rs4434604 | TRIM55 | NM_033058 | 8 | TACCAG|AAG→TACCAG|AGG | 1 | Delete E | CAGAAG | Loss | |

| rs7862221 | TSC1 | NM_000368 | 14 | CTTCAG|AAG→CTTCAG|AGG | 1 | Delete E | CAGAAG | Loss | |

| rs11574323 | WRN | NM_000553 | 23 | GGGTAG|AAT→GGGTAG|AAG | 2 | QS versus H | TAGAAT | Gain | |

| rs2275992 | ZFP91h | NM_170768 | 5 | TTTTAG|TAG→TTTTAG|TGG | 31:7 | 2 | Delete S | TAGTAG | Loss |

| rs200925 | ZNF248 | NM_021045 | 5 | TAACAG|GGT→TAGCAG|GGT | 1 | Insert A | TAACAG | Gain |

Note.— NA = sequence context not available in panTro1.

9-nt acceptor context; reference genome sequence is on the left, and SNP allele is on the right. Polymorphic position is shown in bold italics.

Number of mRNA and ESTs that match the E:I transcripts (shown only if both transcripts are EST confirmed).

Phase of the intron or 5′/3′ UTR.

Impact of alternative NAGNAG splicing on the protein sequence.

Chimpanzee sequence orthologous to human NAGNAG.

Gain = plausible NAGNAG in one of the human alleles and no or implausible NAGNAG in chimpanzee; loss = no or implausible NAGNAG in one of the human alleles and plausible NAGNAG in chimpanzee.

Experimentally confirmed within the present study.

Experimentally confirmed elsewhere (Tadokoro et al. 2005).

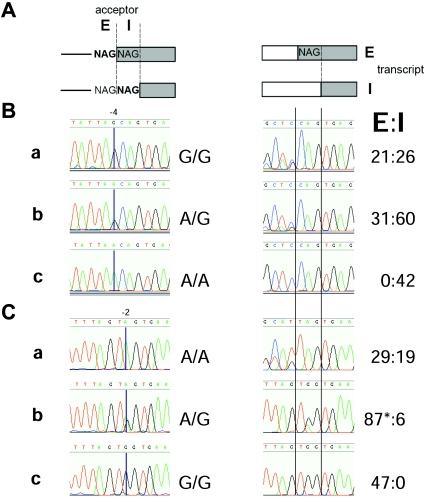

Cases of SNPs that comprise NAGNAG-acceptor and non-NAGNAG–acceptor alleles represent knockout experiments made by nature. We took this opportunity to investigate the assumed correlation between NAGNAG-acceptor genotypes and the appearance of E and I transcripts. Such a study seemed reasonable, since, so far, it has been performed in artificial splicing systems only (Tadokoro et al. 2005). We selected six SNPs with a heterozygosity of >0.2 that affect EST-confirmed HAGHAG acceptors for genotyping and detection of transcript forms. In two cases, we did not find either genotypes with at least one NAGNAG allele or genotypes that are homozygous for the non-NAGNAG allele. In the remaining four cases, we consistently observed E and I transcripts in cells with at least one HAGHAG allele, whereas cells that do not have a HAGHAG acceptor allele produced only one transcript (table 1). This strict correlation between NAGNAG alleles and alternative splicing is illustrated for ZFP91 and TOR1AIP1 in figure 2. These results confirm that NAGNAG motifs are necessary for this type of alternative splicing.

Figure 2.

SNPs that affect plausible NAGNAG acceptors as knockout experiments made by nature. A, Schematic representation of the nomenclature of NAGNAG acceptors (left) and transcripts (right). B, SNP rs2245425 affecting the E acceptor of TOR1AIP1 exon 3 leads to the exclusive expression of the I transcript from the A allele (NAGNAG position −4; for numbering scheme, refer to fig. 1). C, SNP rs2275992 affecting the I acceptor of ZFP91 exon 5 leads to the exclusive expression of the E transcript from the G allele (position −2). Homozygous NAGNAG allele (a), heterozygous (b), and homozygous non-NAGNAG allele (c) are shown as genomic with genotypes (left); cDNA with E:I transcript ratio determined by counting subcloned and sequenced RT-PCR fragments (right). The asterisk (*) denotes E transcripts that can be assigned to the SNP alleles in the I acceptor (A=15; G=72).

Next, we asked whether NAGNAG motifs created by the nonancestral SNP alleles are also sufficient for alternative splicing. With regard to the human reference sequence, in 36 (56%) of 64 cases, a novel NAGNAG is created; in 18 (28%), a known NAGNAG is destroyed by affecting an AG; and in 10 (16%), the N positions are changed. Since the appearance of a SNP allele in the current human genome build is rather random and does not reflect either the relative allele frequency in a defined population or its evolutionary history, the best reference for the question of gain versus loss of NAGNAG acceptors is the UCSC Chimpanzee Genome Browser (panTro1, November 2003). When the sequence context of the 64 plausible NAGNAG-affecting SNPs is compared, for 61 (95%), the orthologous chimpanzee nucleotide is identical to one of both human alleles, which we therefore consider the ancestral one (Watanabe et al. 2004). In 43 cases, the plausible NAGNAG is gained (nonancestral), and, in 18 cases, it is lost (ancestral). Consistent with our assumption that novel plausible NAGNAGs are very likely functional, we found EST evidence of alternative splicing in 16% (7 of 43) (table 4). To provide further experimental support that respective SNP alleles enable alternative NAGNAG splicing, we selected two nonancestral plausible NAGNAGs without EST evidence. As expected, in leukocytes of individuals heterozygous or homozygous for the respective tandem allele of rs5248, we observed the expression of E and I transcripts (GenBank accession numbers DQ082727 and DQ082729) in the ratios 4:14 and 11:7, respectively (table 4). In the case of rs17105087, we were unable to identify the nonancestral allele in our white population sample. By analyzing the human-chimpanzee genomic sequence context of the eight confirmed nonancestral NAGNAG alleles, we found three cases in which both genomes are identical in a long range (rs2287800 [−140/+123 identical nucleotides], rs3765018 [−130/+95 nt], and rs2290647 [−105/+70 nt]). Since most splice enhancers function only within a distance of <100 nt from the affected splice site (Schaal and Maniatis 1999), these findings suggest that NAGNAG motifs are sufficient for alternative splicing in the context of a previously non-NAGNAG acceptor.

Evolutionary Aspects of SNPs in NAGNAG Acceptors

At first glance, surprisingly, the large majority (43 [70%] of 61) of the plausible NAGNAGs are created (35 novel tandem AG alleles and 8 conversions of implausible into plausible), whereas only 18 are destroyed (16 AG destructions and 2 conversions of plausible into implausible). Therefore, we questioned whether there is a trend toward gain-of-NAGNAG acceptors in the human lineage. To test this, we used a null model that maps SNPs to randomly chosen acceptors (see appendix A) and found nearly the same relation for gain and loss of plausible NAGNAG acceptors. Thus, the high number of nonancestral plausible NAGNAGs is presumably a consequence of the fact that NAGNAG motifs represent only 5% of all human acceptors (Hiller et al. 2004). In consequence, in recent primate genomes, a constant bias seems to exist toward the accumulation of NAGNAG acceptors, which leads to an increased complexity of the transcriptome and proteome, antagonized by purifying selection. The question of whether the currently observed NAGNAG fraction among human acceptors represents the saturation level has to be addressed by further comparative genomewide analyses.

Furthermore, we observed striking differences in the numbers of SNPs that affect the AG of the E or I acceptor in ancestral plausible and implausible NAGNAGs, respectively. For the 16 ancestral plausible HAGHAGs, the E acceptor is affected in 11 cases and the I acceptor in 5. In contrast, for 22 implausible HAGGAGs (one ancestral GAGGAG and two GAGHAGs were omitted), we found 5 and 17 cases, respectively (Fisher’s exact test P=.00766). Interestingly, we observed the same trend by comparing all 138 human NAGNAGs that are not conserved in the chimpanzee genome (one GAGGAG and seven GAGHAGs were omitted). The I acceptors of 79 HAGHAGs are affected in 56% (44), whereas the GAG of 59 HAGGAGs is affected in 83% (49) (Fisher’s exact test P=.0009). Implausible GAGGAG and GAGHAG motifs were not considered, since the number of cases is too small.

Since tandem acceptors are nonrandomly distributed in the human genome, with a bias toward intron phase 1 and toward single-aa indels in phase 1 and 2, we questioned whether the nonancestral plausible NAGNAGs are also biased. Indeed, these NAGNAGs show the same bias toward intron phase 1, and they also have a strong tendency to result in single-aa indels (table 5). Thus, the process of establishing SNPs that are relevant for alternative NAGNAG splicing in the human population seems to be a nonrandom process that is subject to the same evolutionary forces as the maintenance of the tandem acceptors themselves.

Table 5.

Intron Phase Distribution and Single aa Events of Nonancestral Plausible NAGNAG Acceptors[Note]

|

No. (%) of Introns by Phase |

||||

| Acceptor | 0 | 1 | 2 | No. (%) ofSingle-aa Events,Phases 1 and 2 |

| Nonancestral NAGNAG allelesa | 12 (31.6) | 16 (42.1) | 10 (26.3) | 24 (92.3) |

| Nonpolymorphic confirmed NAGNAGsb | 349 (39.8) | 379 (43.2) | 150 (17.0) | 487 (92.1) |

Note.— Only NAGNAGs that are located upstream of a coding exon are considered.

Plausible polymorphic NAGNAGs for which the chimpanzee acceptor has no NAGNAG.

EST/mRNA-confirmed NAGNAGs (Hiller et al. 2004).

Discussion

Since splicing variations are coming more and more into the research focus of human molecular genetics (Lopez-Bigas et al. 2005), novel approaches are needed to identify splice-relevant SNPs. By data mining the SNP annotation of the UCSC Human Genome Browser, we identified 121 variations that may affect alternative splicing by creation, destruction, or changing of NAGNAG acceptors. To improve the specificity of our prediction, we classified NAGNAG acceptors into “plausible” (HAGHAG) and “implausible” (GAGHAG, HAGGAG, or GAGGAG) ones. This subdivision of the tandem acceptors, primarily based on the degree of confirmation by mRNA and EST data, is further supported by (1) the fact that GAG acceptors are very rare (Stamm et al. 2000), (2) our genomewide observation that only plausible and not implausible NAGNAGs have the same bias toward intron phase 1 as experimentally confirmed NAGNAGs (Hiller et al. 2004), and (3) the observed differences in the numbers of SNPs that affect the AG of the E or I acceptor in ancestral plausible and implausible NAGNAGs, respectively. The last indicates that the selection pressure to maintain the E acceptor for HAGGAGs is higher than the pressure to preserve the coding sequence, since destruction of the HAG acceptor will leave a GAG that is unlikely to act as an acceptor site. In contrast, for plausible HAGHAGs, destruction of either AG is much less deleterious, since the other will still function as an acceptor. Thus, the identified 64 SNPs in plausible NAGNAGs are highly predictive of variations in alternative splicing. Nevertheless, it represents an experimental and bioinformatic challenge for future research to elucidate what makes the rare cases of confirmed implausible NAGNAG acceptors.

Although it seems obvious that the disruption of a plausible NAGNAG acceptor abolishes the formation of alternative transcripts, SNPs in these motifs provide us with unique knockout experiments by nature to confirm this hypothesis experimentally. Analyzing the expression of E and I transcripts in cells with at least one HAGHAG allele or without HAGHAG alleles, we have shown that the NAGNAG motif is necessary for this type of alternative splicing. In a subsequent analysis, we asked whether NAGNAG motifs created by the nonancestral SNP alleles allow alternative splicing. Usually, the introduction of an AG anywhere in the pre-mRNA does not create a functional acceptor site, since a polypyrimidine tract upstream and possibly enhancer sequences are required for recognition by the spliceosome. However, we suppose that the creation of a second AG 3 bases up or downstream of an existing acceptor is very likely to result in a functional tandem acceptor, since the splice-relevant sequence context is already present.

Referring to the chimpanzee genome as the reference for ancestral SNP alleles, we found EST and RT-PCR evidence that novel plausible NAGNAGs are most likely functional. This implies that a change of a normal acceptor to a plausible NAGNAG acceptor by a single mutation is sufficient to enable alternative splicing. Although the mechanism of NAGNAG splicing is not understood in detail, our findings argue against a general involvement of signals other than the NAGNAG itself. Thus, we conclude that SNPs in plausible NAGNAGs have an influence on NAGNAG splicing, regardless of whether the NAGNAG is ancestral. However, additional signals might be necessary for regulation of alternative splicing at tandem receptors.

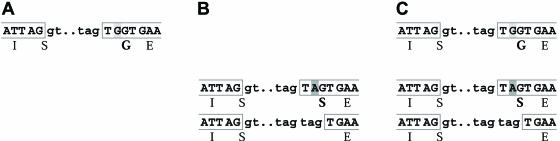

Most interestingly, 23% (15 of 64) of SNPs in plausible NAGNAGs are translationally nonsilent and, thus, introduce a novel dimension of variability on the protein level by changing the I acceptor and the aa sequence of the E protein. Whereas homozygotes express either one or two isoforms, heterozygosity results in three different proteins (fig. 3). As listed in the Human Gene Mutation Database, the aa change can be dramatic—for example, as from Glu to the oppositely charged Lys in PAPSS2 (rs17173698), which leads to a decrease in immunoreactive protein (Xu et al. 2002). However, the third isoform of the protein generated by alternative NAGNAG splicing had not been taken into consideration. Moreover, it is conceivable that some of the SNPs in NAGNAG acceptors that allow the formation of three protein isoforms in heterozygotes may confer a heterozygous advantage.

Figure 3.

SNP affecting the I acceptor and the aa sequence of the E protein (rs2275992 in ZFP91). Homozygosity of the G allele without a NAGNAG results in the expression of one protein (A), homozygosity of the A allele with the NAGNAG results in two (B), and heterozygosity results in three isoforms (C). All three transcripts are confirmed by at least four ESTs/mRNAs. The two allele variants are highlighted in light and dark gray. Amino acids are shown below the second codon position. Upper- and lowercase letters indicate exonic and intronic nucleotides, respectively. Exons are boxed.

Alternative splicing at tandem acceptors can result in the gain/loss of a premature stop codon in the mRNA. Among SNPs affecting plausible NAGNAGs, the G allele of SNP rs9644946 changes the acceptor context of GOLGA1 exon 8 from AAATAG to AAGTAG. Since intron 7 resides in phase 0, an inframe TAG insertion would be the consequence if the novel E acceptor is used. Interestingly, the gene codes for an autoantigen associated with Sjogren syndrome (MIM 270150). Since the E acceptor is preferred in alternative NAGNAG splicing (Hiller et al. 2004), the novel AAG acceptor is likely to be functional. The resulting E transcript is a candidate for nonsense-mediated mRNA decay (Maquat 2004). Thus, the AAGTAG allele would result in a lower protein expression. Alternatively, it is possible that the mRNA containing the premature stop codon escapes degradation, and the truncated protein may exhibit autoantigenic properties. It remains to be elucidated in populations with a sufficiently high allele frequency (e.g., 0.099 in the PERLEGEN panel that contains 24 samples of Chinese descent), regardless of whether alternative splicing at the AAGTAG acceptor contributes to the disease.

A second example of potential disease relevance is the SNP rs363209, the G allele of which creates a novel plausible AAGCAG acceptor of intron 6 in APPBP1 (GenBank accession number NM_003905). The APP-BP1 protein binds to the carboxyl-terminal region of the amyloid precursor protein (APP) and interacts with the ubiquitin-activating enzyme E1C (UBE1C [homolog to yeast Uba3]) in the process of neddylation (Walden et al. 2003). APP plays a central role in Alzheimer disease and Down syndrome. Dysfunction of the APP-BP1 interaction with APP has been suggested to be one cause of Alzheimer disease (Chen 2004). The protein-protein interactions of the APP-BP1 E and I isoforms may be different and modulate the respective processes. It should be mentioned that the UBE1C gene (GenBank accession number NM_003968) itself contains a tandem acceptor (CAGAAG in front of exon 11). This may further increase the flexibility of the neddylation process by all four combinations of the E/I protein isoforms from two genes each.

The disease relevance of a NAGNAG SNP is demonstrated for the ABCA4 gene (Maugeri et al. 1999). Maugeri et al. (1999) describe a NAGNAG mutation (2588G→C, changing the acceptor site TAGGAG→TAGCAG) that has a much higher frequency in patients with Stargardt disease 1 (STGD1 [MIM 248200]) and that is assumed to be a mild mutation that causes STGD1 in combination with a severe ABCA4 mutation. By experimental analysis of the splice patterns of two patients with STGD1 who carry the mutation and one control individual, they found that only the alleles with the TAGCAG produce two splice forms. Our study exactly predicts this mutation outcome.

In general, most of the SNPs that are described in the present study—in particular, these in plausible NAGNAGs—affect the E:I transcript ratio, depending on the cell’s genotype. SNP alleles with a destroyed E acceptor cause the exclusive expression of the I transcript. Alleles that destroy an I acceptor result in an exclusive expression of the longer E transcript. SNPs that comprise a plausible and an implausible NAGNAG allele will seriously hamper or disable splicing at the GAG acceptor. It has already been shown that a change in the ratio of alternative splice forms can cause diseases. For example, the change in the ratio of the alternative MAPT transcripts containing three or four microtubule-binding repeats may be causal for frontotemporal dementia (MIM 600274) (Spillantini et al. 1998). Another example is the WT1 gene, in which alternative donor usage results in two protein isoforms that differ in 3 aa (+KTS/−KTS isoforms) and function (Englert et al. 1995). The altered ratio of +KTS/−KTS leads to Frasier syndrome (MIM 136680) (Barbaux et al. 1997). This situation is similar to that of NAGNAG acceptors, since E/I protein isoforms are observed that have functional differences (Condorelli et al. 1994; Tadokoro et al. 2005).

Altogether, 28% (18 of 64) of the plausible NAGNAG SNPs occur in known disease genes (table 6). Thus, they are preferable candidates for more-detailed functional analysis and association studies to link alternative splicing with diseases. Currently, there are no general methods that allow the prediction of splice-relevant SNPs. Focusing on SNPs that affect NAGNAG acceptors, we present a highly effective approach for the identification of SNPs that result in variations in alternative splicing patterns.

Table 6.

Human Disease Genes with SNPs Affecting Plausible NAGNAG Acceptors

| dbSNP ID | Gene Symbol | RefSeq ID | Disease | MIM Number(s) | PubMed ID(s) |

| rs3020724 | CYP17A1 | NM_000102 | Adrenal hyperplasia, congenital | #202110, *609300 | 4303304 |

| rs12042060 | FIBL-6 | NM_031935 | Age-related macular degeneration | #603075, *608548 | 14570714 |

| rs2243187 | IL19 | NM_153758 | Asthma | *605687 | 15557163 |

| rs8176139 | BRCA1 | NM_007304 | Breast cancer | *113705, #114480 | 9167459 |

| rs11567804 | C3AR1 | NM_004054 | Bronchial asthma | *605246 | 15278436 |

| rs3025420 | DBH | NM_000787 | Congenital dopamine-beta-hydroxylase deficiency | #223360, *609312 | 14991826 |

| rs2409496 | GART | NM_175085 | Down syndrome | *138440 | 9328467 |

| rs1804783 | CACNA1A | NM_023035 | Episodic ataxia-2, familial hemiplegic migraine, spinocerebellar ataxia-6, idiopathic generalized epilepsy | #183086, #141500, #108500, *601011 | 8988170, 8898206, 9302278 |

| rs2010657 | GGT1 | NM_013421 | Glutathionuria | +231950 | 238530, 7623451 |

| rs2307130 | AGL | NM_000644 | Glycogen storage disease type III | +232400 | 9032647, 10925384 |

| rs1833783 | FTL | NM_000146 | Hyperferritinemia-cataract syndrome | #600886, *134790 | 7493028, 12199804 |

| rs11661706 | EPB41L3 | NM_012307 | Meningioma, lung cancer | *605331 | 10888600, 9892180 |

| rs2275992 | ZFP91 | NM_170768 | Acute myeloid leukemia | #601626 | 12738986, |

| rs1071716 | TPM2 | NM_213674 | Nemaline myopathy-4, distal arthrogryposis 1 | #609285, #108120, *190990 | 11738357, 12592607 |

| rs2521612 | SLC4A1 | NM_000342 | Renal tubular acidosis, ovalocytosis, spherocytosis | #179800, 166900, +109270 | 9600966, 1737855, 9973643 |

| rs9644946 | GOLGA1 | NM_002077 | Sjogren syndrome | 270150, *602502 | 9324025 |

| rs17173698 | PAPSS2 | NM_004670 | Spondyloepimetaphyseal dysplasia | *603005 | 9714015 |

| rs9606756 | TCN2 | NM_000355 | Transcobalamin II deficiency | +275350 | 14632784 |

| rs7862221 | TSC1 | NM_000368 | Tuberous sclerosis | #191100, *605284 | 12773162, 14551205 |

| rs11574323 | WRN | NM_000553 | Werner syndrome | #277700, *604611 | 9012406, 8968742 |

Acknowledgments

The skillful technical assistance of Ivonne Görlich is gratefully acknowledged. This work was supported by German Ministry of Education and Research grants 01GS0426 (to S.S.) and 01GR0105 and 0312704E (to M.P.) as well as Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft grant SFB604-02 (to M.P.).

Appendix A: Randomization Null Model for NAGNAG SNPs

To assess whether there is a preference for creating plausible NAGNAGs, we used a simulation that assigns a new acceptor to the 2.896 SNPs that overlap an acceptor in the 9-nt context and evaluates a possible NAGNAG-relevant outcome. For the 2,896 SNPs, we blasted the 101-nt genomic context (50 nt upstream and 50 nt downstream of the SNP) against the chimpanzee genome to determine the ancestral allele variant. We kept alignments with at least 95% identity and no mismatches in a ±5-nt context around the SNP position. This yielded a total of 2,439 SNPs. Then, we blasted the 103-nt contexts (50 nt up- and downstream of the acceptor NAG) of 10,000 human acceptor sites (excluding the acceptors that are overlapped by a known SNP) against the chimpanzee genome and kept 8,082 for which we found an alignment (95% identity and no mismatch ±10 nt around the NAG). Then, we assigned a new acceptor (randomly chosen from the 8,082) to a given SNP. We chose an acceptor with the ancestral allele variant at the respective position (e.g., if a SNP changes a C→G at position 4 of the 9-nt context, the new acceptor must also have a C at position 4). Since a methylated C in a CG context frequently mutates to a T, we assigned a new acceptor with the same sequence context at this position if the SNP represents a C→T mutation in a CG context (or a G→A mutation in a GC context on the opposite strand). This assures that context-dependent mutations are simulated in the same context. If a new acceptor is assigned to a SNP, we evaluated the possible impact on a NAGNAG acceptor. For each of the 2,439 SNPs, we successively assigned 10 randomly chosen acceptors (avoiding duplicate assignments).

The whole procedure was repeated 10 times, with different starts of the random-number generator. We calculated the following statistics from the 10 runs: (1) minimum and maximum percentage of creation versus destruction of a plausible NAGNAG, (2) minimum and maximum percentage of changes from a plausible to an implausible NAGNAG versus changes from an implausible to a plausible NAGNAG, and (3) minimum and maximum percentage of “gain of plausible NAGNAG” versus “loss of plausible NAGNAG.” “Gain of plausible NAGNAG” is the sum of created, plausible NAGNAGs and changes from implausible to plausible. “Loss of plausible NAGNAG” is the sum of destroyed, plausible NAGNAGs and changes from plausible to implausible. These values were compared with the observed values by Fisher’s exact test. For (1), we obtained P values between .52 and .75, for (2), P values between .72 and 1, and, for (3), P values between .66 and .88. Thus, the observed bias toward “gain of plausible NAGNAG” is comparable to the expectation.

Web Resources

Accession numbers and URLs for data presented herein are as follows:

- dbEST, ftp://ftp.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/blast/db/FASTA/est_human.gz (for the human portion of dbEST)

- GenBank, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Genbank/ (for the human mRNA download, ZFP91 [accession number NM_170768], DTX2 [accession numbers DQ082728 and DQ082730], CMA1 [accession numbers DQ082727 and DQ082729]), APPBP1 [accession number NM_003905], and UBE1C [accession number NM_003968])

- Human Gene Mutation Database, http://www.uwcm.ac.uk/uwcm/mg/hgmd0.html

- Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM), http://www.ncbi.nlm.gov/Omim/ (for Sjogren syndrome, STGD1, frontotemporal dementia, and Frasier syndrome)

- UCSC Chimpanzee Genome Browser, http://hgdownload.cse.ucsc.edu/goldenPath/PANTro1/bigZips/ (for source download panTro1 [November 2003])

- UCSC Human Genome Browser, http://hgdownload.cse.ucsc.edu/goldenPath/hg17/bigZips/ (for source download hg17)

References

- Barbaux S, Niaudet P, Gubler MC, Grunfeld JP, Jaubert F, Kuttenn F, Fekete CN, Souleyreau-Therville N, Thibaud E, Fellous M, McElreavey K (1997) Donor splice-site mutations in WT1 are responsible for Frasier syndrome. Nat Genet 17:467–470 10.1038/ng1297-467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cartegni L, Chew SL, Krainer AR (2002) Listening to silence and understanding nonsense: exonic mutations that affect splicing. Nat Rev Genet 3:285–298 10.1038/nrg775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen YZ (2004) APP induces neuronal apoptosis through APP-BP1-mediated downregulation of β-catenin. Apoptosis 9:415–422 10.1023/B:APPT.0000031447.05354.9f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Condorelli G, Bueno R, Smith RJ (1994) Two alternatively spliced forms of the human insulin-like growth factor I receptor have distinct biological activities and internalization kinetics. J Biol Chem 269:8510–8516 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Englert C, Vidal M, Maheswaran S, Ge Y, Ezzell RM, Isselbacher KJ, Haber DA (1995) Truncated WT1 mutants alter the subnuclear localization of the wild-type protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 92:11960–11964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredman D, White SJ, Potter S, Eichler EE, Den Dunnen JT, Brookes AJ (2004) Complex SNP-related sequence variation in segmental genome duplications. Nat Genet 36:861–866 10.1038/ng1401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Blanco MA, Baraniak AP, Lasda EL (2004) Alternative splicing in disease and therapy. Nat Biotechnol 22:535–546 10.1038/nbt964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiller M, Huse K, Szafranski K, Jahn N, Hampe J, Schreiber S, Backofen R, Platzer M (2004) Widespread occurrence of alternative splicing at NAGNAG acceptors contributes to proteome plasticity. Nat Genet 36:1255–1257 10.1038/ng1469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karinch AM, deMello DE, Floros J (1997) Effect of genotype on the levels of surfactant protein A mRNA and on the SP-A2 splice variants in adult humans. Biochem J 321:39–47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ke X, Hunt S, Tapper W, Lawrence R, Stavrides G, Ghori J, Whittaker P, Collins A, Morris AP, Bentley D, Cardon LR, Deloukas P (2004) The impact of SNP density on fine-scale patterns of linkage disequilibrium. Hum Mol Genet 13:577–588 10.1093/hmg/ddh060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long M, Deutsch M (1999) Association of intron phases with conservation at splice site sequences and evolution of spliceosomal introns. Mol Biol Evol 16:1528–1534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Bigas N, Audit B, Ouzounis C, Parra G, Guigo R (2005) Are splicing mutations the most frequent cause of hereditary disease? FEBS Lett 579:1900–1903 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.02.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch KW, Weiss A (2001) A CD45 polymorphism associated with multiple sclerosis disrupts an exonic splicing silencer. J Biol Chem 276:24341–24347 10.1074/jbc.M102175200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maquat LE (2004) Nonsense-mediated mRNA decay: splicing, translation and mRNP dynamics. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 5:89–99 10.1038/nrm1310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maugeri A, van Driel MA, van de Pol DJR, Klevering BJ, van Haren FJJ, Tijmes N, Bergen AAB, Rohrschneider K, Blankenagel A, Pinckers AJLG, Dahl N, Brunner HG, Deutman AF, Hoyng CB, Cremers FPM (1999) The 2588G→C mutation in the ABCR gene is a mild frequent founder mutation in the Western European population and allows the classification of ABCR mutations in patients with Stargardt disease. Am J Hum Genet 64:1024–1035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagani F, Baralle FE (2004) Genomic variants in exons and introns: identifying the splicing spoilers. Nat Rev Genet 5:389–396 10.1038/nrg1327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaal TD, Maniatis T (1999) Multiple distinct splicing enhancers in the protein-coding sequences of a constitutively spliced pre-mRNA. Mol Cell Biol 19:261–273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spillantini MG, Murrell JR, Goedert M, Farlow MR, Klug A, Ghetti B (1998) Mutation in the tau gene in familial multiple system tauopathy with presenile dementia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95:7737–7741 10.1073/pnas.95.13.7737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamm S, Zhu J, Nakai K, Stoilov P, Stoss O, Zhang MQ (2000) An alternative-exon database and its statistical analysis. DNA Cell Biol 19:739–756 10.1089/104454900750058107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tadokoro K, Yamazaki-Inoue M, Tachibana M, Fujishiro M, Nagao K, Toyoda M, Ozaki M, Ono M, Miki N, Miyashita T, Yamada M (2005) Frequent occurrence of protein isoforms with or without a single amino acid residue by subtle alternative splicing: the case of Gln in DRPLA affects subcellular localization of the products. J Hum Genet 50:382–394 10.1007/s10038-005-0261-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taudien S, Galgoczy P, Huse K, Reichwald K, Schilhabel M, Szafranski K, Shimizu A, Asakawa S, Frankish A, Loncarevic IF, Shimizu N, Siddiqui R, Platzer M (2004) Polymorphic segmental duplications at 8p23.1 challenge the determination of individual defensin gene repertoires and the assembly of a contiguous human reference sequence. BMC Genomics 5:92 10.1186/1471-2164-5-92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentonyte R, Hampe J, Huse K, Rosenstiel P, Albrecht M, Stenzel A, Nagy M, Gaede KI, Franke A, Haesler R, Koch A, Lengauer T, Seegert D, Reiling N, Ehlers S, Schwinger E, Platzer M, Krawczak M, Muller-Quernheim J, Schurmann M, Schreiber S (2005) Sarcoidosis is associated with a truncating splice site mutation in BTNL2. Nat Genet 37:357–364 10.1038/ng1519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walden H, Podgorski MS, Schulman BA (2003) Insights into the ubiquitin transfer cascade from the structure of the activating enzyme for NEDD8. Nature 422:330–334 10.1038/nature01456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe H, Fujiyama A, Hattori M, Taylor TD, Toyoda A, Kuroki Y, Noguchi H, et al (2004) DNA sequence and comparative analysis of chimpanzee chromosome 22. Nature 429:382–388 10.1038/nature02564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu ZH, Freimuth RR, Eckloff B, Wieben E, Weinshilboum RM (2002) Human 3′-phosphoadenosine 5′-phosphosulfate synthetase 2 (PAPSS2) pharmacogenetics: gene resequencing, genetic polymorphisms and functional characterization of variant allozymes. Pharmacogenetics 12:11–21 10.1097/00008571-200201000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]