To the Editor:

We read with interest “Identification of a Major Recombination Hotspot in Patients with Short Stature and SHOX Deficiency” (Schneider et al. 2005). We have characterized 30 unrelated subjects—from kindreds with Leri-Weill dyschondrosteosis (LWD [MIM 127300]) ascertained from U.S. and Canadian clinics focused on genetics, pediatric endocrinology, and orthopedic hand surgery—on the basis of short stature and/or Madelung wrist deformity (Ross et al. 2001). Patients with karyotypic abnormalities were excluded. SHOX [MIM 312865] deletions were identified by FISH with cosmids LLNOYCO3′M′34F5 and/or LLNOYCO3′M′15D10 (Rao et al. 1997), as described elsewhere (Wei et al. 2001), by genotyping the SHOX-CA microsatellite marker (Belin et al. 1998), located at nucleotides 540504–540660 of the human X chromosome (May 2004; hg17) assembly (UCSC Genome Browser), or by a commercial diagnostic test for homozygosity of multiple intragenic SNPs (SHOX-DNA-Dx [Esoterix Endocrinology]). Deletions were characterized as follows.

We genotyped probands and available parents for pseudoautosomal markers DXYS233 and DXYS234, respectively, located at nucleotides 868388–868748 and 1711448–1711779 of the X chromosome (hg17), by capillary electrophoresis by use of fluorescent-labeled primers selected from the GDB Human Genome Database. Markers that showed two alleles of distinct size were scored as “not deleted.” Markers that showed only one size allele were scored as “deleted” (hemizygous) if inspection of the pedigree revealed noninheritance of a parental allele or as “uninformative” if homozygosity could not be excluded. Table 1 shows representative genotyping data for proband SW575 and her parents. It is apparent that this proband inherited null alleles of SHOX-CA and DXYS233 from her father, which implies a deletion encompassing both these markers (deletion of SHOX was confirmed by FISH; data not shown). DXYS234 was uninformative in this kindred.

Table 1.

Genotyping Data for SW575 Trio

|

Allele Size(bp) |

|||

| Subject | SHOX-CA | DXYS233 | DXYS234 |

| SW575 | 138 | 282 | 246 |

| Father | 140 | 274 | 246 |

| Mother | 138,152 | 274,282 | 246 |

We also generated human-hamster somatic-cell hybrid clones that retained the deleted X chromosome but not the other human sex chromosome, for 11 probands or their first-degree relatives, and we mapped the deletions by STS content mapping (table 2), using PCR assays designed from publicly available pseudoautosomal sequence. All PCRs gave the expected product from a positive control (X-only hybrid GM06318) and from probands’ genomic DNA and no product from hamster DNA. Finally, we mapped the deletion breakpoint proximal to DXYS234 in one proband, by FISH, with BAC RPCI3-431I1, near the pseudoautosomal boundary (Ross et al. 2000).

Table 2.

STS Content-Mapping Data for Hybrids[Note]

|

STS Position on the X Chromosome Sequencea |

|||||||||||||

| Proband | 401599to 401819 | 413340to 413779 | 516318to 516686 | 521289to 521370 | 549537to 549738 | 565237to 565698(SHOX exon 3) | 597765to 598234 | 868388to 868748(DXYS233) | 1000510to 1001758 | 1093641to 1093815 | 1182168to 1182351 | 1415973to 1416498 | 1499109to 1499293 |

| 316 | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | |

| 325 | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | |

| 368 | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | ||||

| 378 | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + |

| 447 | − | − | − | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||

| 467 | + | − | − | − | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||

| 507 | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | |

| 575 | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + |

| 598 | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | |

| 617 | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + |

| 619 | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + |

Note.— Deleted intervals are shaded in gray.

From the human (May 2004; hg17) assembly (UCSC Genome Browser).

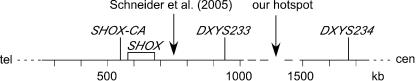

Our results (table 3) differed markedly from those reported by Schneider et al. (2005). DXYS233 was deleted in 17 (65%) of 26 of our informative cases, as compared with 6 (18%) of 33 cases reported by Schneider et al. (2005). By contrast, a similarly small proportion of deletions encompassed DXYS234 in our sample (3/27; 11%) and that of Schneider et al. (2005) (4/31; 13%), inferred from their figure 1 (DXYS234 maps just proximal to ANT3). Our genotyping and STS content-mapping results were concordant in cases in which both data were available. The proximal breakpoint in 8 (72%) of our 11 hybrids mapped to the same ∼150-kb gap between contigs NT_086931 and NT_086933. Thus, we found a recombination hotspot several hundred kilobases proximal to the hotspot reported by Schneider et al. (2005) (fig. 1).

Table 3.

Deletions of Markers DXYS233 and DXYS234 by Ethnicity

|

DXYS233 |

DXYS234 |

|||||

| Race/Ethnicity | No.Deleted | No.Not Deleted | No.Uninformative | No.Deleted | No.Not Deleted | No.Uninformative |

| White, not Hispanic (n=23) | 11 | 8 | 4 | 3 | 17 | 3 |

| White, Hispanic (n=7) | 6 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

7 |

0 |

| Total (n=30) | 17 | 9 | 4 | 3 | 24 | 3 |

Figure 1.

Diagram showing relative locations of SHOX gene (box), microsatellite markers, contigs (horizontal lines), and deletion breakpoint hotspots. Scale is numbered according to human (May 2004; hg17) assembly (UCSC Genome Browser).

The reason for this discrepancy is unclear. One difference is the populations studied. Our population included seven Hispanic subjects, six (86%) of whom had deletions at DXYS233, whereas the population studied by Schneider et al. (2005) was European, predominantly German. However, 10/19 (53%) of our non-Hispanic subjects also had deletions at DXYS233. Phenotypic differences are unlikely to explain the discrepancy, since all of our subjects and 27 of the 33 subjects studied by Schneider et al. (2005) had LWD, for which the size of the deletion does not correlate with the severity of the phenotype (Schiller et al. 2000). There are also significant methodological differences between our studies: Schneider et al. (2005) mapped deletions principally by cosmid FISH, with fine mapping by SNP analysis of only seven families, whereas we used primarily microsatellite marker–segregation analysis and somatic cell hybrid STS content mapping. Our result is not likely to be due to false paternity, since we did not observe any nonparental genotypes. It is possible that either or both studies were confounded by segmental duplications within the pseudoautosomal region, which is known to be enriched in repeats (Ried et al. 1998). In fact, a recent genomewide survey of normal copy-number variation reported a polymorphic duplication at or near SHOX (Sharp et al. 2005). Further mapping of SHOX deletion breakpoints associated with LWD or idiopathic short stature (MIM 604271) in different populations and completion of the pseudoautosomal sequence may shed light on the nature and mechanism of recombination hotspots in this genomic region.

Acknowledgments

We thank Bo Luo and Geetha Kalahasti for generating somatic cell hybrids and STS content mapping. Supported by National Institutes of Health grants NS35554 and NS42777.

Web Resources

The URLs for data presented herein are as follows:

- GDB Human Genome Database, http://www.gdb.org/ (for microsatellite markers DXYS233 and DXYS234)

- Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM), http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Omim/ (for LWD, SHOX, and idiopathic short stature)

- UCSC Genome Browser, http://genome.ucsc.edu (for STS markers at the Human [Homo sapiens] Genome Browser Gateway)

References

- Belin V, Cusin V, Viot G, Girlich D, Toutain A, Moncla A, Vekemans M, Le Merrer M, Munnich A, Cormier-Daire V (1998) SHOX mutations in dyschondrosteosis (Leri-Weill syndrome). Nat Genet 19:67–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao E, Weiss B, Fukami M, Rump A, Niesler B, Mertz A, Muroya K, Binder G, Kirsch S, Winkelmann M, Nordsiek G, Heinrich U, Breuning MH, Ranke MB, Rosenthal A, Ogata T, Rappold GA (1997) Pseudoautosomal deletions encompassing a novel homeobox gene cause growth failure in idiopathic short stature and Turner syndrome. Nat Genet 16:54–63 10.1038/ng0597-54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ried K, Rao E, Schiebel K, Rappold GA (1998) Gene duplications as a recurrent theme in the evolution of the human pseudoautosomal region 1: isolation of the gene ASMTL. Hum Mol Genet 7:1771–1778 10.1093/hmg/7.11.1771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross JL, Roeltgen D, Kushner H, Wei F, Zinn AR (2000) The Turner syndrome–associated neurocognitive phenotype maps to distal Xp. Am J Hum Genet 67:672–681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross JL, Scott C Jr, Marttila P, Kowal K, Nass A, Papenhausen P, Abboudi J, Osterman L, Kushner H, Carter P, Ezaki M, Elder F, Wei F, Chen H, Zinn AR (2001) Phenotypes associated with SHOX deficiency. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 86:5674–5680 10.1210/jc.86.12.5674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiller S, Spranger S, Schechinger B, Fukami M, Merker S, Drop SL, Troger J, Knoblauch H, Kunze J, Seidel J, Rappold GA (2000) Phenotypic variation and genetic heterogeneity in Leri-Weill syndrome. Eur J Hum Genet 8:54–62 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider KU, Sabherwal N, Jantz K, Röth R, Muncke N, Blum WF, Cutler GB Jr, Rappold G (2005) Identification of a major recombination hotspot in patients with short stature and SHOX deficiency. Am J Hum Genet 77:89–96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp AJ, Locke DP, McGrath SD, Cheng Z, Bailey JA, Vallente RU, Pertz LM, Clark RA, Schwartz S, Segraves R, Oseroff VV, Albertson DG, Pinkel D, Eichler EE (2005) Segmental duplications and copy-number variation in the human genome. Am J Hum Genet 77:78–88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei F, Cheng S, Badie N, Elder F, Scott C Jr, Nicholson L, Ross JL, Zinn AR (2001) A man who inherited his SRY gene and Leri-Weill dyschondrosteosis from his mother and neurofibromatosis type 1 from his father. Am J Med Genet 102:353–358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]