Abstract

Epileptic seizures are more common in males than in females. One of the areas that have recently been implicated in the higher susceptibility of males to seizures is the substantia nigra reticulata (SNR). Several studies support the existence of phenotypic differences between male and female infantile SNR neurons and particularly in several aspects of the GABAergic system, including its ability to control seizures. We have recently found that at postnatal day 14-17 (PN14-17) rats, which are equivalent to infants, activation of GABAA receptors has different physiological effects in male and female SNR neurons. This is likely due to the differences in the expression of the neuronal-specific potassium-chloride cotransporter KCC2, which regulates the intracellular chloride concentration. In male PN14-17 SNR neurons, GABAA receptor activation with muscimol causes depolarization and increments in intracellular calcium concentration and the expression of calcium regulated genes, such as KCC2. Blockade of L-type voltage sensitive calcium channels (L-VSCC) by nifedipine decreases KCC2 mRNA expression. In PN14-17 females, however, muscimol hyperpolarizes the SNR neurons, does not increase intracellular calcium and decreases KCC2 mRNA expression. In PN15 females, nifedipine has no effect on KCC2 mRNA expression in the SNR. This sexually dimorphic function of GABAA receptors also creates divergent patterns of estradiol signaling. In male PN15 rats, estradiol decreases KCC2 mRNA expression in SNR neurons. Pretreatment with the GABAA receptor antagonist bicuculline or with nifedipine, prevents the appearance of estradiol-mediated downregulation of KCC2 mRNA expression. In contrast, in PN15 females, estradiol does not influence KCC2 expression. These show that, in infantile rats, drugs or conditions that modulate the activity of GABAA receptors or L-VSCCs have different effects on the differentiation of the SNR. As a result, they have the potency of causing long-term changes in the function of the SNR in the control of seizures, movement and the susceptibility to and course of epilepsy and movement disorders.

Keywords: GABA receptors, KCC2, sexual dimorphism, substantia nigra reticulata, seizures

Introduction

The substantia nigra reticulata (SNR) is involved in the control of movement and seizures (1-17). Interestingly, the incidence of certain seizure and movement disorders is different in men and women. Epilepsy or unprovoked seizures are more common in males, although in most population studies this difference is small (18, 19). A potential confounding factor is the inclusion of patients with different ages and heterogeneous epileptic syndromes. When looking at specific syndromes, we encounter a male predominance in many pediatric syndromes, such as the severe and benign myoclonic epilepsies of infancy, or the autosomal dominant epilepsy with febrile seizures plus. Males also appear to be more vulnerable to acute symptomatic seizures (20, 21). In certain experimental models of epilepsy, sex differences in the susceptibility to certain types of seizures, seizure-induced damage, or response to antiepileptics have been reported (22-27).

A male predominance has also been reported in incidence studies on Tourette syndrome (28, 29) and Parkinson’s disease (30), which have been linked to an underlying dysfunction of the substantia nigra. Such observations have triggered a line of research to understand the pathophysiologic factors responsible for the higher susceptibility of men to these disorders. In this article, I will summarize the evidence supporting that the SNR is sexually dimorphic and will present our recent data that implicate GABAA receptors as broadcasters of sexually differentiating signals, which may prepare the male and female SNR to assume different functional roles in controlling seizures and possibly movement.

Sexual dimorphism of rodent SNR

The differences between the male and female SNR probably start prenatally, with the peak of neurogenesis during embryonal life appearing earlier in female than in male rat SNR (31). Postnatally, sex differences in the expression of androgen and estrogen receptors emerge, and these may influence the responsiveness to the differentiating effects of sex hormones (32, 33). The dimorphic features of the GABAA receptor system are particularly important, since the major synaptic input to the SNR is comprised of GABAergic synapses (34-36). Moreover, SNR neurons are primarily GABAergic (37) and contain GABAA receptors (38-40). In vivo studies have demonstrated that the GABAA-responsive SNR neurons of male and female rats have distinct physiological properties and functions. SNR neurons from anesthetized adult male rats develop tolerance to chronic benzodiazepine administration, as well as rebound increase in spontaneous firing upon administration of benzodiazepine antagonist, whereas those from ovariectomized females do not (41). Using intranigral infusions of the GABAA receptor agonist in developing rats, Veliskova and Moshé have shown sex, age, and site-specific effects on the threshold to flurothyl seizures, which are altered by testosterone administration during the early postnatal life (42). But what are the mechanisms underlying these divergent functions? The explanations may be multifold, ranging from qualitative and quantitative differences in the expression of molecules that influence GABAA receptor or other neurotransmitter signaling pathways, in the connectivity with other structures, in synaptic and morphological attributes of the GABAergic SNR neurons, as well as in humoral factors. Previous studies have documented sex differences in the GABAergic system of the rat SNR. For instance, the female SNR has higher GABA levels than the male (38, 43), whereas GABA turnover appears to be higher in males (44). The subunit composition of GABAA receptors also differs, with an increased neuronal expression and relative abundance of the α1 subunit in female SNR neurons (38, 45). This may result in different pharmacological and physiological properties. Moreover, as the subsequent sections will demonstrate, GABAA receptor activation elicits distinct physiologic responses in male and female SNR neurons.

Sex-specific KCC2 expression and functional maturation of GABAA receptors in rat SNR

The initial report by Ben-Ari and colleagues (46) and many subsequent studies (47-51) have established the dual role of GABAA receptors during development. Immature neurons have high intracellular chloride ([Cl−]i) and as a result GABAA receptor activation depolarizes them, activates voltage-sensitive calcium channels (VSCCs), and increases intracellular calcium ([Ca++]i). This results in activation of many calcium-regulated intracellular processes, including gene transcription and neuronal differentiation. Mature neurons, in contrast, have low [Cl−]i and this allows GABAA receptor agonists to cause neuronal hyperpolarization without activating VSCCs. Recently, a neuronal-specific isoform of the potassium chloride cotransporters, KCC2, was shown to be important facilitator of this functional switch, by controlling [Cl−]i (52). Low expression of KCC2, as occurs in immature neurons, is not sufficient in lowering ([Cl−]i) and as a result the increased [Cl−]i facilitates depolarizing responses to GABAA receptor activation. During development, KCC2 expression gradually increases in most brain structures, lowers [Cl−]i and permits the appearance of hyperpolarizing responses to GABAA receptor activation (52, 53).

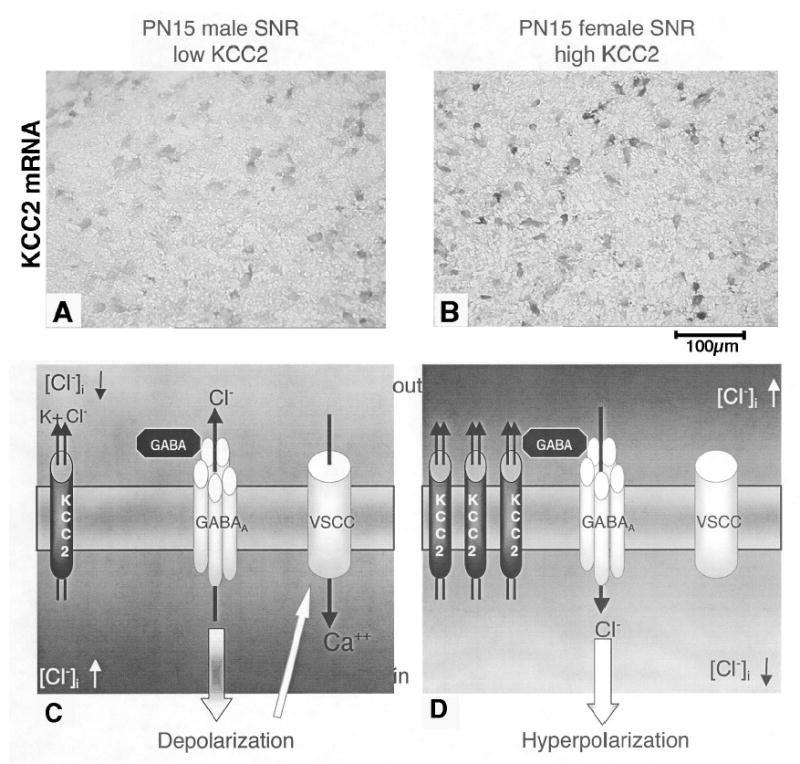

To test whether similar functional differences in GABAA receptor physiology occur between sexes, KCC2 expression in rat SNR was correlated with GABAA receptor function. Using a KCC2 specific digoxigenin labeled in situ hybridization technique, sex, age and region specific differences in KCC2 mRNA expression were found in SNR neurons of PN15, PN30, and adult males and PN15 and PN30 female rats (54). Males always had lower KCC2 mRNA expression in their SNR compared with age-matched females. KCC2 mRNA expression increased between PN15 and PN30 in both sexes but plateaued thereafter in males. Anteroposterior differences were also present after PN30, with the anterior SNR neurons expressing more KCC2 mRNA compared with the posterior. Interestingly, comparison of KCC2 mRNA expression with the ability of intranigral muscimol infusions to elicit pro- or anticonvulsant effects in the flurothyl seizure model, as characterized by Veliskova and Moshé (42), revealed a very good correlation. The groups that responded to intranigral muscimol with proconvulsant effects had low KCC2 mRNA in their SNR, whereas the groups in which muscimol infusions had anticonvulsant effects expressed high KCC2 mRNA levels (54). These suggested that perhaps KCC2 regulates the sex, age and region-specific role of the SNR in seizure control by altering the electrophysiological properties of the SNR neurons. Indeed, in gramicidin-perforated patch clamp and fura-2AM imaging experiments, bath application of muscimol in acute SNR slices from male PN14-17 rats caused depolarizations and increments in [Ca++]i. In contrast, in females, muscimol-induced currents were hyperpolarizing and not associated with changes in [Ca++]i (54) (Figure 1). Since GABAA receptor activation in adult male SNR neurons results in hyperpolarizing currents, these findings suggest that the functional maturation of the GABAA receptors during development is delayed in males.

Figure 1. Sex differences in KCC2 and GABAA receptor function in PN15 rat SNR.

Panels A and B: KCC2-specific digoxigenin labeled in situ hybridization of PN15 SNR sections. Male SNR neurons (panel A) express lower KCC2 mRNA than female (panel B) SNR neurons. Panel C: In PN15 male SNR, the low KCC2 expression neurons results in high intracellular chloride concentration. Upon GABA-mediated activation of GABAA receptors, chloride efflux ensues, followed by depolarization, activation of voltage-sensitive calcium channels (VSCCs) and increase in intracellular calcium. Panel D: In PN15 female SNR neurons, the high KCC2 expression is sufficient to lower intracellular chloride. As a result, activation of GABAA receptors leads to influx of chloride, hyperpolarization, without affecting the activity of VSCCs.

Dual effects of GABAA receptors on calcium-regulated gene expression

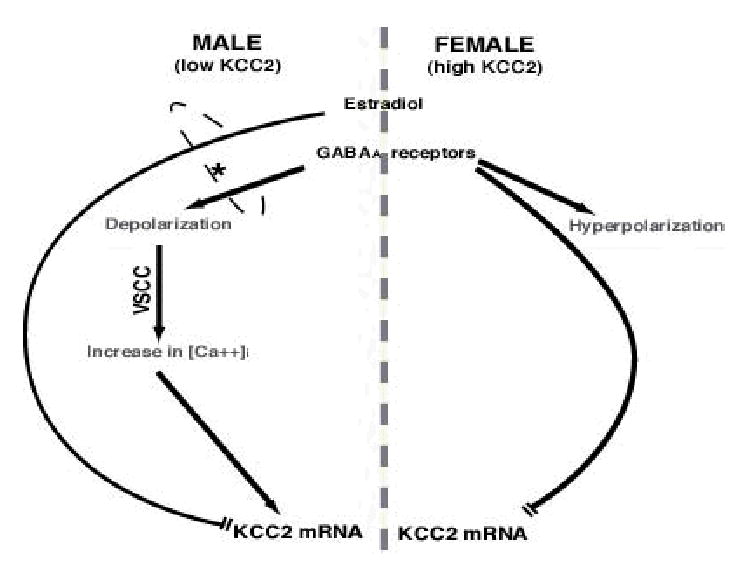

Since GABAA receptor activation regulates [Ca++]i in male but not in female infantile SNR, we hypothesized that this would result in sex-specific regulation of gene expression. Indeed, using KCC2 as a target gene, we have shown that modulators of GABAA receptor or L-type VSCCs (L-VSCCs) have distinct regulatory effects on its expression in PN15 male and female SNR neurons in vivo (54). In males, muscimol increased whereas the L-VSCC blocker nifedipine decreased KCC2 mRNA expression in the SNR. These findings are in agreement with Ganguly et al (55) who showed that GABA can accelerate the developmental switch of GABAA receptors. In PN15 female SNR neurons, however, muscimol decreased KCC2 mRNA but nifedipine had no effect (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Sexually dimorphic regulatory pathways affecting KCC2 mRNA expression in PN15 male and female rat SNR neurons.

In male PN15 rats, GABAA receptor or L-type VSCC (L-VSCC) activation increases KCC2 mRNA expression, whereas estradiol downregulates KCC2 mRNA expression. The asterisk indicates that estradiol-mediated downregulation of KCC2 mRNA occurs only when GABA-mediated activation of L-VSCCs is present. In female PN15 rats however, GABAA receptor activation downregulates KCC2 mRNA, whereas estradiol has no effect.

GABAA receptors broadcast sexual differentiating signals in infantile rat SNR, in response to estradiol

To understand the regulatory mechanisms controlling KCC2 expression in rat SNR, we studied the effects of sex hormones (56). Interestingly, administration of 17β-estradiol downregulated KCC2 mRNA expression in the SNR of PN15 male rats within 4 hours but had no effect in females. These effects were already present within 4 hours, and persisted after repeated doses (PN13-15). The observation that regulation of KCC2 by GABAA receptor induced increments in [Ca++]i and estradiol both occurred in males but not in females generated the hypothesis that perhaps there is an interaction or interdependence of these two signaling pathways. Indeed, pretreatment of male PN15 rats with blockers of GABAA receptors, ie bicuculline, or with nifedipine, prevented the appearance of estradiol-mediated downregulation of KCC2 mRNA (56). Estradiol therefore requires the presence of L-VSCCs activated by GABAA receptors in order to regulate KCC2 expression (Figure 2).

Sex differences in GABAA receptor function in other brain regions

Divergent effects of GABAA receptor activation have also been reported in the neonatal hypothalamus. Systemic injections of muscimol in neonatal rats (PN0) increase the expression of the phosphorylated form of the cAMP responsive element binding protein (phospho-CREB) in the ventromedial hypothalamus, the medial preoptic area and the CA1 area of the hippocampus but not in the arcuate nucleus (57). The muscimol-induced increase in phospho-CREB in these areas was inhibited by pretreatment with the L-type voltage sensitive calcium channel blocker nimodipine (58). These observations could suggest that a similar sexual dimorphism in the function of native GABAA receptors and expression of cation chloride cotransporters may exist in some of these structures. To date, studies in neonatal pups of male or unspecified sex have provided ample evidence that GABAA receptor activation elicits depolarizing responses in the neonatal life in both these structures and hyperpolarizing effects later on during development (59, 60). Persistence however of depolarizing effects of GABA in certain populations of adult hypothalamic cells have been reported, which correlate with absence or low expression of KCC2 in these cells (61) (62). Correlation of GABAA receptor function and electrophysiology with chloride cotransporter expression in specific subpopulations of cells of the same model system would be needed to derive definite conclusions as to the existence of sex differences in structures other than the SNR.

Conclusions

These data provide the first evidence that the expression of a cation-chloride cotransporter, KCC2, changes not only as a function of age but also of sex. Although direct modulation of KCC2 expression in the SNR may be necessary to firmly establish a cause and effect relationship between sex differences in KCC2 expression and GABAA receptor function, this is strongly supported by the existing literature (52, 53). The ensuing differences in GABAA receptor physiology appear to influence the sex, age and region specific role of the SNR in seizure control. It would be interesting to speculate whether KCC2 or other related molecules that regulate chloride homeostasis may be implicated in pediatric epilepsy syndromes, especially those that exhibit male preponderance. To this end, it would also be worth examining whether similar sex differences in cation chloride cotransporters and GABAA receptor function exist in other cortical and subcortical structures involved in seizure generation and propagation.

Male SNR neurons retain the “immature type” phenotype of GABAA receptors for longer developmental periods compared to females. As a result, activation of GABAA receptors in male SNR neurons may have long term trophic, proliferating, and differentiating effects, promoting thus the sexual differentiation of the SNR and its role in seizure or movement control (63, 64). Furthermore, the use of drugs acting on GABAA receptors or L-VSCCs, as many antiepileptic agents do, or conditions that modulate these receptor systems, such as seizures, may have different long term differentiating effects on the male and female SNR, during vulnerable developmental periods. The dependence of estradiol-mediated regulation of KCC2 expression upon the presence of GABA-mediated activation of L-VSCCs is especially relevant since sex hormones, and estrogens in particular, have been implicated in the differentiation and masculinization of the brain (33). First, our findings suggest that one of the factors defining the critical period during which certain structures, such as the SNR, and certain calcium-regulated genes, such as KCC2, are sensitive to the differentiating and trophic effects of estrogens may indeed be the presence of GABA-mediated depolarization and calcium rises. Second, during developmental periods characterized by sexually dimorphic functions of GABAA receptors, such as the PN14-17 rat SNR, GABAA receptors broadcast different signals in male and female neurons responding to estradiol, further promoting the sexual differentiation of the structure.

Finally, the dual regulation of KCC2 mRNA by GABAA receptor agonists, under conditions that they may trigger depolarizing or hyperpolarizing responses, may indeed act as a feedback mechanism to prevent excess excitation or inhibition when prolonged or excessive stimulation of GABAA receptors occurs. Further documentation at the protein level or electrophysiology is however needed.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by NIH/NINDS grants NS45243 and NS20253. Permission to upload this material was granted by Blackwell Publishing.

References

- 1.Iadarola MJ, Gale K. Substantia nigra: site of anticonvulsant activity mediated by gamma- aminobutyric acid. Science. 1982;218(4578):1237–40. doi: 10.1126/science.7146907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garant DS, Gale K. Lesions of substantia nigra protect against experimentally induced seizures. Brain Res. 1983;273(1):156–61. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(83)91105-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garcia-Cairasco N, Sabbatini RM. Role of the substantia nigra in audiogenic seizures: a neuroethological analysis in the rat. Braz J Med Biol Res. 1983;16(2):171–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Le Gal La Salle G, Kaijima M, Feldblum S. Abortive amygdaloid kindled seizures following microinjection of gamma- vinyl-GABA in the vicinity of substantia nigra in rats. Neurosci Lett. 1983;36(1):69–74. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(83)90488-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McNamara JO, Rigsbee LC, Galloway MT. Evidence that Substantia Nigra is crucial to neural network of kindled seizures. Eur J Pharmacol. 1983;86(3–4):485–6. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(83)90202-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Sarro G, Meldrum BS, Reavill C. Anticonvulsant action of 2-amino-7-phosphonoheptanoic acid in the substantia nigra. Eur J Pharmacol. 1984;106(1):175–9. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(84)90692-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bonhaus DW, Walters JR, McNamara JO. Activation of substantia nigra neurons: role in the propagation of seizures in kindled rats. J Neurosci. 1986;6(10):3024–30. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.06-10-03024.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Okada R, Moshe SL, Wong BY, Sperber EF, Zhao DY. Age-related substantia nigra-mediated seizure facilitation. Exp Neurol. 1986;93(1):180–7. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(86)90157-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Turski L, Cavalheiro EA, Schwarz M, Turski WA, De Moraes Mello LE, Bortolotto ZA, Klockgether T, Sontag KH. Susceptibility to seizures produced by pilocarpine in rats after microinjection of isoniazid or gamma-vinyl-GABA into the substantia nigra. Brain Res. 1986;370(2):294–309. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(86)90484-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Loscher W, Czuczwar SJ, Jackel R, Schwarz M. Effect of microinjections of gamma-vinyl GABA or isoniazid into substantia nigra on the development of amygdala kindling in rats. Exp Neurol. 1987;95(3):622–38. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(87)90304-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sperber EF, Wong BY, Wurpel JN, Moshe SL. Nigral infusions of muscimol or bicuculline facilitate seizures in developing rats. Brain Res. 1987;465(1–2):243–50. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(87)90245-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Depaulis A, Snead OC, 3rd, Marescaux C, Vergnes M. Suppressive effects of intranigral injection of muscimol in three models of generalized non-convulsive epilepsy induced by chemical agents. Brain Res. 1989;498(1):64–72. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(89)90399-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moshe SL, Albala BJ. Nigral muscimol infusions facilitate the development of seizures in immature rats. Brain Res. 1984;315(2):305–8. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(84)90165-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Evarts EV, Wise SP. Basal ganglia outputs and motor control. Ciba Found Symp. 1984;107:83–102. doi: 10.1002/9780470720882.ch6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Turski L, Klockgether T, Turski W, Schwarz M, Sontag KH. Substantia nigra and motor control in the rat: effect of intranigral alpha-kainate and gamma-D-glutamylaminomethylsulphonate on motility. Brain Res. 1987;424(1):37–48. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(87)91190-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arnt J, Scheel-Kruger J, Magelund G, Krogsgaard-Larsen P. Muscimol and related GABA receptor agonists: the potency of GABAergic drugs in vivo determined after intranigral injection. J Pharm Pharmacol. 1979;31(5):306–13. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1979.tb13506.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.DiChiara G, Olianas M, Del Fiacco M, Spano PF, Tagliamonte A. Intranigral kainic acid is evidence that nigral non-dopaminergic neurones control posture. Nature. 1977;268(5622):743–5. doi: 10.1038/268743a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hauser WA, Incidence and prevalence., in Epilepsy: A Comprehensive Textbook, Engel JJ and Pedley WA, Editors. 1997, Lippincott-Raven: Philadelphia. p. 47–57. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kotsopoulos IA, van Merode T, Kessels FG, de Krom MC, Knottnerus JA. Systematic review and meta-analysis of incidence studies of epilepsy and unprovoked seizures. Epilepsia. 2002;43(11):1402–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.2002.t01-1-26901.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hauser WA, Annegers JF, Rocca WA. Descriptive epidemiology of epilepsy: contributions of population-based studies from Rochester, Minnesota. Mayo Clin Proc. 1996;71(6):576–86. doi: 10.4065/71.6.576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Farwell JR, Blackner G, Sulzbacher S, Adelman L, Voeller M. First febrile seizures. Characteristics of the child, the seizure, and the illness. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 1994;33(5):263–7. doi: 10.1177/000992289403300502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tan M, Tan U. Sex difference in susceptibility to epileptic seizures in rats: importance of estrous cycle. Int J Neurosci. 2001;108(3–4):175–91. doi: 10.3109/00207450108986513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Galanopoulou AS, Alm EM, Veliskova J. Estradiol reduces seizure-induced hippocampal injury in ovariectomized female but not in male rats. Neurosci Lett. 2003;342(3):201–205. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(03)00282-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kalkbrenner KA, Standley CA. Estrogen modulation of NMDA-induced seizures in ovariectomized and non-ovariectomized rats. Brain Res. 2003;964(2):244–9. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)04065-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mejias-Aponte CA, Jimenez-Rivera CA, Segarra AC. Sex differences in models of temporal lobe epilepsy: role of testosterone. Brain Res. 2002;944(1–2):210–8. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)02691-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Medina AE, Manhaes AC, Schmidt SL. Sex differences in sensitivity to seizures elicited by pentylenetetrazol in mice. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2001;68(3):591–6. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(01)00466-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Matejovska I, Veliskova J, Velisek L. Bicuculline-induced rhythmic EEG episodes: gender differences and the effects of ethosuximide and baclofen treatment. Epilepsia. 1998;39(12):1243–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1998.tb01321.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nomura Y, Segawa M. Neurology of Tourette’s syndrome (TS) TS as a developmental dopamine disorder: a hypothesis. Brain Dev. 2003;25(Suppl 1):S37–42. doi: 10.1016/s0387-7604(03)90007-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Freeman RD, Fast DK, Burd L, Kerbeshian J, Robertson MM, Sandor P. An international perspective on Tourette syndrome: selected findings from 3,500 individuals in 22 countries. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2000;42(7):436–47. doi: 10.1017/s0012162200000839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bower JH, Maraganore DM, McDonnell SK, Rocca WA. Influence of strict, intermediate, and broad diagnostic criteria on the age- and sex-specific incidence of Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2000;15(5):819–25. doi: 10.1002/1531-8257(200009)15:5<819::aid-mds1009>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Galanopoulou AS, Liptakova S, Veliskova J, Moshé SL. Sex and regional differences in the time and patterns of neurogenesis of the rat substantia nigra. Epilepsia. 2001;42(Suppl 7):109. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ravizza T, Galanopoulou AS, Veliskova J, Moshe SL. Sex differences in androgen and estrogen receptor expression in rat substantia nigra during development: an immunohistochemical study. Neuroscience. 2002;115(3):685–96. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00491-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cooke B, Hegstrom CD, Villeneuve LS, Breedlove SM. Sexual differentiation of the vertebrate brain: principles and mechanisms. Front Neuroendocrinol. 1998;19(4):323–62. doi: 10.1006/frne.1998.0171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grofova I. The identification of striatal and pallidal neurons projecting to substantia nigra. An experimental study by means of retrograde axonal transport of horseradish peroxidase. Brain Res. 1975;91(2):286–91. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(75)90550-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ribak CE, Vaughn JE, Saito K, Barber R, Roberts E. Immunocytochemical localization of glutamate decarboxylase in rat substantia nigra. Brain Res. 1976;116(2):287–98. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(76)90906-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smith Y, Bolam JP. Neurons of the substantia nigra reticulata receive a dense GABA-containing input from the globus pallidus in the rat. Brain Res. 1989;493(1):160–7. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(89)91011-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gonzalez-Hernandez T, Rodriguez M. Compartmental organization and chemical profile of dopaminergic and GABAergic neurons in the substantia nigra of the rat. J Comp Neurol. 2000;421(1):107–35. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(20000522)421:1<107::aid-cne7>3.3.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ravizza T, Friedman LK, Moshe SL, Veliskova J. Sex differences in GABA(A)ergic system in rat substantia nigra pars reticulata. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2003;21(5):245–54. doi: 10.1016/s0736-5748(03)00069-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schwarzer C, Berresheim U, Pirker S, Wieselthaler A, Fuchs K, Sieghart W, Sperk G. Distribution of the major gamma-aminobutyric acid(A) receptor subunits in the basal ganglia and associated limbic brain areas of the adult rat. J Comp Neurol. 2001;433(4):526–49. doi: 10.1002/cne.1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pirker S, Schwarzer C, Wieselthaler A, Sieghart W, Sperk G. GABA(A) receptors: immunocytochemical distribution of 13 subunits in the adult rat brain. Neuroscience. 2000;101(4):815–50. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00442-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wilson MA. Gonadectomy and sex modulate spontaneous activity of substantia nigra pars reticulata neurons without modifying GABA/benzodiazepine responsiveness. Life Sci. 1993;53(3):217–25. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(93)90672-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Veliskova J, Moshe SL. Sexual dimorphism and developmental regulation of substantia nigra function. Ann Neurol. 2001;50(5):596–601. doi: 10.1002/ana.1248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Flugge G, Wuttke W, Fuchs E. Postnatal development of transmitter systems: sexual differentiation of the GABAergic system and effects of muscimol. Int J Dev Neurosci. 1986;4(4):319–26. doi: 10.1016/0736-5748(86)90049-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Manev H, Pericic D. Sex difference in the turnover of GABA in the rat substantia nigra. J Neural Transm. 1987;70(3–4):321–8. doi: 10.1007/BF01253606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Facciolo RM, Alo R, Tavolaro R, Canonaco M, Franzoni MF. Dimorphic features of the different alpha-containing GABA-A receptor subtypes in the cortico-basal ganglia system of two distantly related mammals (hedgehog and rat) Exp Brain Res. 2000;130(3):309–19. doi: 10.1007/s002219900246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ben-Ari Y, Cherubini E, Corradetti R, Gaiarsa JL. Giant synaptic potentials in immature rat CA3 hippocampal neurones. J Physiol. 1989;416:303–25. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1989.sp017762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Staley KJ, Mody I. Shunting of excitatory input to dentate gyrus granule cells by a depolarizing GABAA receptor-mediated postsynaptic conductance. J Neurophysiol. 1992;68(1):197–212. doi: 10.1152/jn.1992.68.1.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Reichling DB, Kyrozis A, Wang J, MacDermott AB. Mechanisms of GABA and glycine depolarization-induced calcium transients in rat dorsal horn neurons. J Physiol. 1994;476(3):411–21. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang J, Reichling DB, Kyrozis A, MacDermott AB. Developmental loss of GABA- and glycine-induced depolarization and Ca2+ transients in embryonic rat dorsal horn neurons in culture. Eur J Neurosci. 1994;6(8):1275–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1994.tb00317.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Owens DF, Boyce LH, Davis MB, Kriegstein AR. Excitatory GABA responses in embryonic and neonatal cortical slices demonstrated by gramicidin perforated-patch recordings and calcium imaging. J Neurosci. 1996;16(20):6414–23. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-20-06414.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yuste R, Katz LC. Control of postsynaptic Ca2+ influx in developing neocortex by excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmitters. Neuron. 1991;6(3):333–44. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90243-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rivera C, Voipio J, Payne JA, Ruusuvuori E, Lahtinen H, Lamsa K, Pirvola U, Saarma M, Kaila K. The K+/Cl− co-transporter KCC2 renders GABA hyperpolarizing during neuronal maturation. Nature. 1999;397(6716):251–5. doi: 10.1038/16697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hubner CA, Stein V, Hermans-Borgmeyer I, Meyer T, Ballanyi K, Jentsch TJ. Disruption of KCC2 reveals an essential role of K-Cl cotransport already in early synaptic inhibition. Neuron. 2001;30(2):515–24. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00297-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Galanopoulou AS, Kyrozis A, Claudio OI, Stanton PK, Moshe SL. Sex-specific KCC2 expression and GABA(A) receptor function in rat substantia nigra. Exp Neurol. 2003;183(2):628–37. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4886(03)00213-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ganguly K, Schinder AF, Wong ST, Poo M. GABA itself promotes the developmental switch of neuronal GABAergic responses from excitation to inhibition. Cell. 2001;105(4):521–32. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00341-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Galanopoulou AS, Moshe SL. Role of sex hormones in the sexually dimorphic expression of KCC2 in rat substantia nigra. Exp Neurol. 2003;184(2):1003–9. doi: 10.1016/S0014-4886(03)00387-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Auger AP, Perrot-Sinal TS, McCarthy MM. Excitatory versus inhibitory GABA as a divergence point in steroid-mediated sexual differentiation of the brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(14):8059–64. doi: 10.1073/pnas.131016298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Perrot-Sinal TS, Auger AP, McCarthy MM. Excitatory actions of GABA in developing brain are mediated by l-type Ca2+ channels and dependent on age, sex, and brain region. Neuroscience. 2003;116(4):995–1003. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00794-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gao XB, van den Pol AN. GABA, not glutamate, a primary transmitter driving action potentials in developing hypothalamic neurons. J Neurophysiol. 2001;85(1):425–34. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.85.1.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ben-Ari Y. Excitatory actions of gaba during development: the nature of the nurture. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002;3(9):728–39. doi: 10.1038/nrn920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.DeFazio RA, Heger S, Ojeda SR, Moenter SM. Activation of A-type gamma-aminobutyric acid receptors excites gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons. Mol Endocrinol. 2002;16(12):2872–91. doi: 10.1210/me.2002-0163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Leupen SM, Tobet SA, Crowley WF, Jr, Kaila K. Heterogeneous expression of the potassium-chloride cotransporter KCC2 in gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons of the adult mouse. Endocrinology. 2003;144(7):3031–6. doi: 10.1210/en.2002-220995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Spoerri PE. Neurotrophic effects of GABA in cultures of embryonic chick brain and retina. Synapse. 1988;2(1):11–22. doi: 10.1002/syn.890020104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Berninger B, Marty S, Zafra F, da Penha Berzaghi M, Thoenen H, Lindholm D. GABAergic stimulation switches from enhancing to repressing BDNF expression in rat hippocampal neurons during maturation in vitro. Development. 1995;121(8):2327–35. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.8.2327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]