Abstract

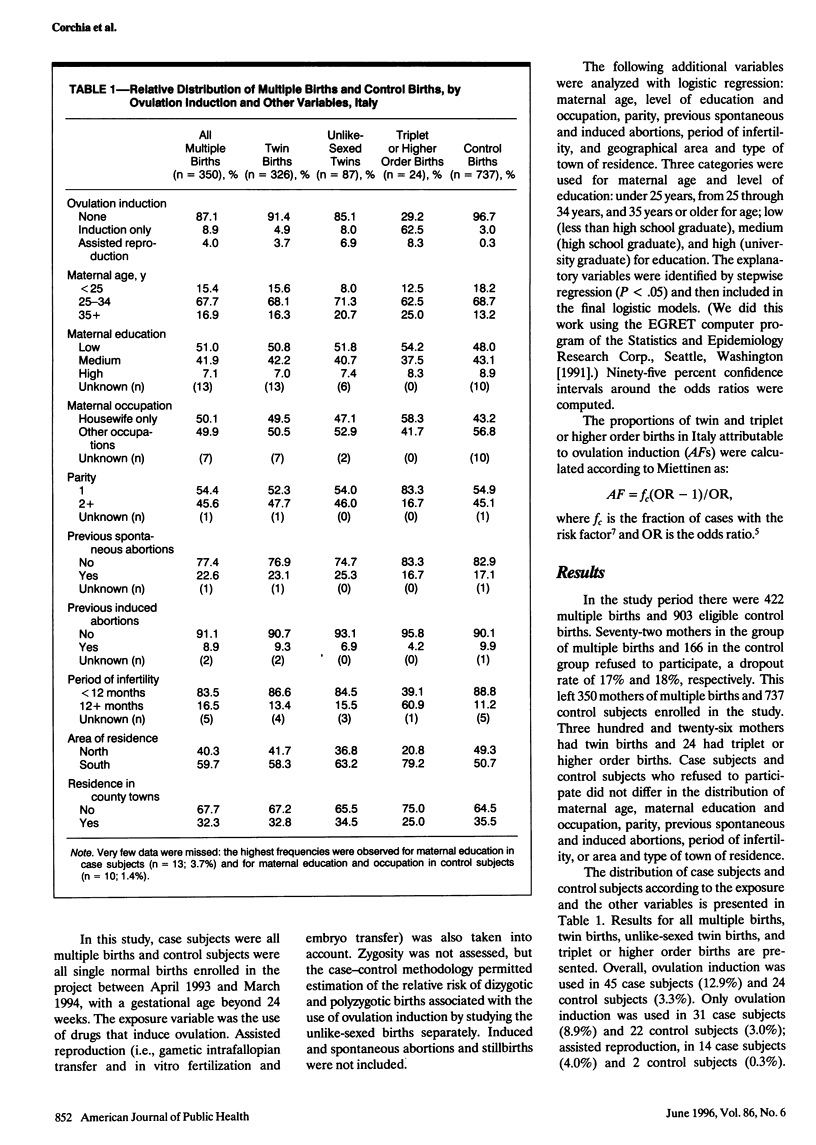

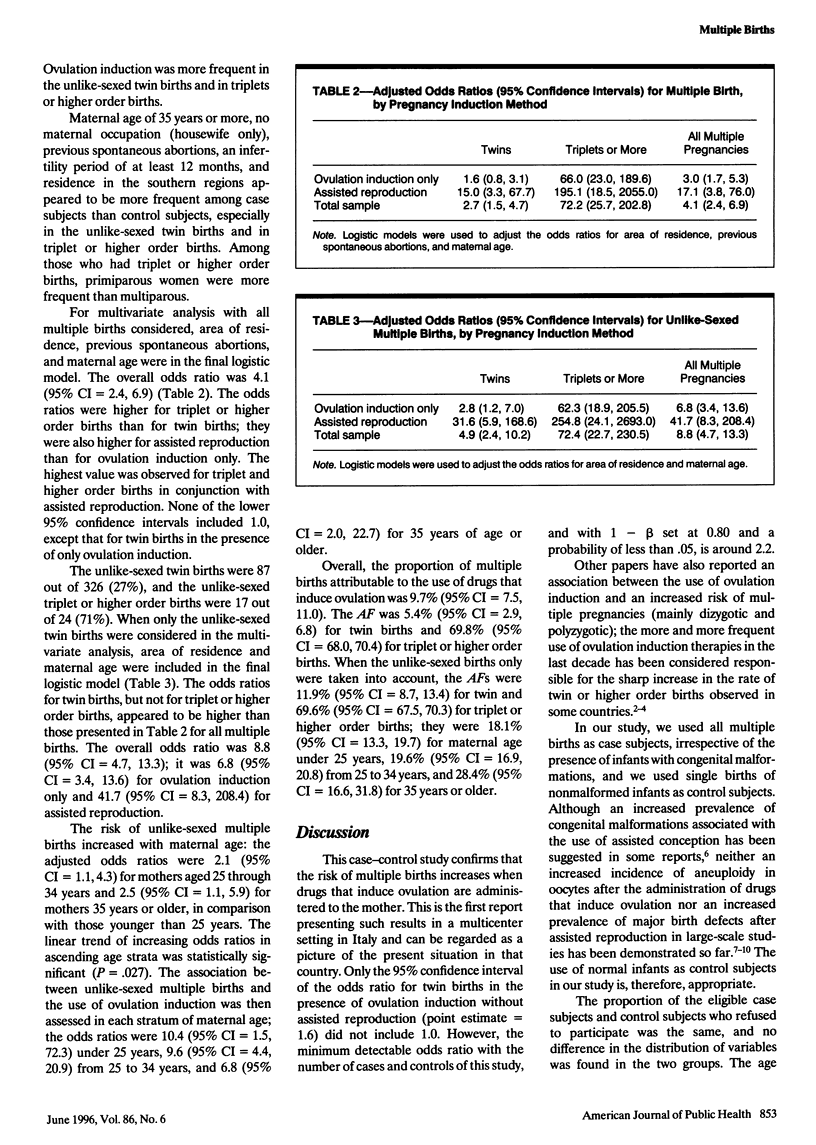

OBJECTIVES: This study evaluated the increase in risk of multiple births associated with ovulation induction and calculated the proportion of multiple births attributable to this treatment. METHODS: Cases were 350 multiple births and controls were 737 single births enrolled from April 1993 to March 1994 in the Mercurio Project, an investigation of reproductive outcomes in Italy. RESULTS: Ovulation induction was used in 45 case births (12.9%) and 24 control births (3.3%); the adjusted odds ratio was 4.1 (95% confidence interval [CI] = 2.4, 6.9). The odds ratio for triplet or higher order births was 72.2 (95% CI = 25.7, 202.8). When unlike-sexed multiple births were considered, the odds ratio increased for twin births, but not for triplet or higher births. The highest odds ratios were found when ovulation induction was used with assisted reproduction. The proportion of multiple births attributable to ovulation induction was 9.7% overall, 5.4% for twin births, and 69.8% for triplet or higher births. CONCLUSIONS: Ovulation induction increases the risk of multiple births and has been responsible for the rise in the rate of triplet or higher order births in Italy in the last decade. Its indiscriminate and improper use should be avoided.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Callahan T. L., Hall J. E., Ettner S. L., Christiansen C. L., Greene M. F., Crowley W. F., Jr The economic impact of multiple-gestation pregnancies and the contribution of assisted-reproduction techniques to their incidence. N Engl J Med. 1994 Jul 28;331(4):244–249. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199407283310407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derom C., Derom R., Vlietinck R., Maes H., Van den Berghe H. Iatrogenic multiple pregnancies in East Flanders, Belgium. Fertil Steril. 1993 Sep;60(3):493–496. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezra Y., Schenker J. G. Appraisal of in vitro fertilization. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1993 Feb;48(2):127–133. doi: 10.1016/0028-2243(93)90253-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gras L., McBain J., Trounson A., Kola I. The incidence of chromosomal aneuploidy in stimulated and unstimulated (natural) uninseminated human oocytes. Hum Reprod. 1992 Nov;7(10):1396–1401. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a137581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keith L. G., Papiernik E., Luke B. The costs of multiple pregnancy. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1991 Oct;36(2):109–114. doi: 10.1016/0020-7292(91)90764-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levene M. I., Wild J., Steer P. Higher multiple births and the modern management of infertility in Britain. The British Association of Perinatal Medicine. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1992 Jul;99(7):607–613. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1992.tb13831.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Licata D., Garzena E., Mostert M., Farinasso D., Fabris C. Congenital malformations in babies born after assisted conception. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 1993 Apr;7(2):222–223. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.1993.tb00397.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miettinen O. S. Proportion of disease caused or prevented by a given exposure, trait or intervention. Am J Epidemiol. 1974 May;99(5):325–332. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a121617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parazzini F., Tozzi L., Mezzanotte G., Bocciolone L., La Vecchia C., Fedele L., Benzi G. Trends in multiple births in Italy: 1955-1983. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1991 Jun;98(6):535–539. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1991.tb10366.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizk B., Doyle P., Tan S. L., Rainsbury P., Betts J., Brinsden P., Edwards R. Perinatal outcome and congenital malformations in in-vitro fertilization babies from the Bourn-Hallam group. Hum Reprod. 1991 Oct;6(9):1259–1264. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a137523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders D. M., Lancaster P. The wider perinatal significance of the Australian in vitro fertilization data collection program. Am J Perinatol. 1989 Apr;6(2):252–257. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-999587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoham Z., Zosmer A., Insler V. Early miscarriage and fetal malformations after induction of ovulation (by clomiphene citrate and/or human menotropins), in vitro fertilization, and gamete intrafallopian transfer. Fertil Steril. 1991 Jan;55(1):1–11. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)54048-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Vonderweid U., Spagnolo A., Corchia C., Chiandotto V., Chiappe S., Chiappe F., Colarizi P., De Luca T., Didato M., Fertz M. C. Italian multicentre study on very low-birth-weight babies. Neonatal mortality and two-year outcome. Acta Paediatr. 1994 Apr;83(4):391–396. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1994.tb18126.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Duivenboden Y. A., Merkus J. M., Verloove-Vanhorick S. P. Infertility treatment: implications for perinatology. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1991 Dec 13;42(3):201–204. doi: 10.1016/0028-2243(91)90220-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]