Abstract

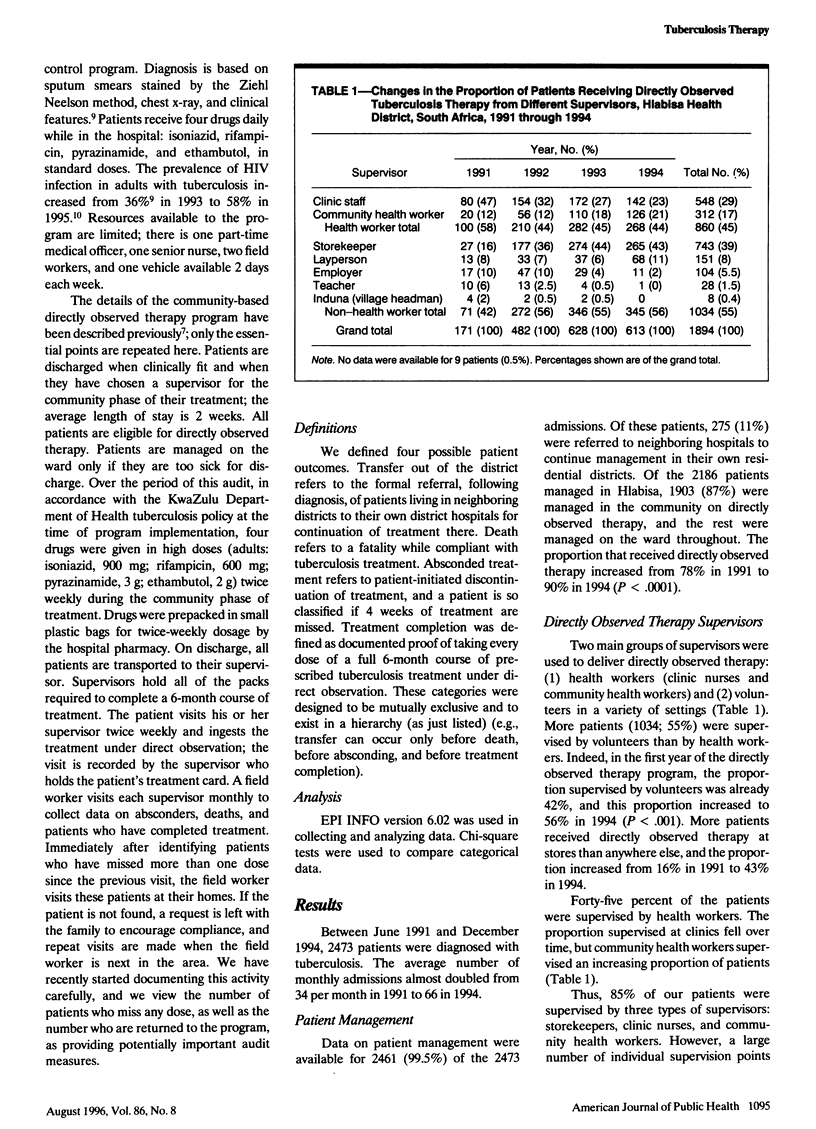

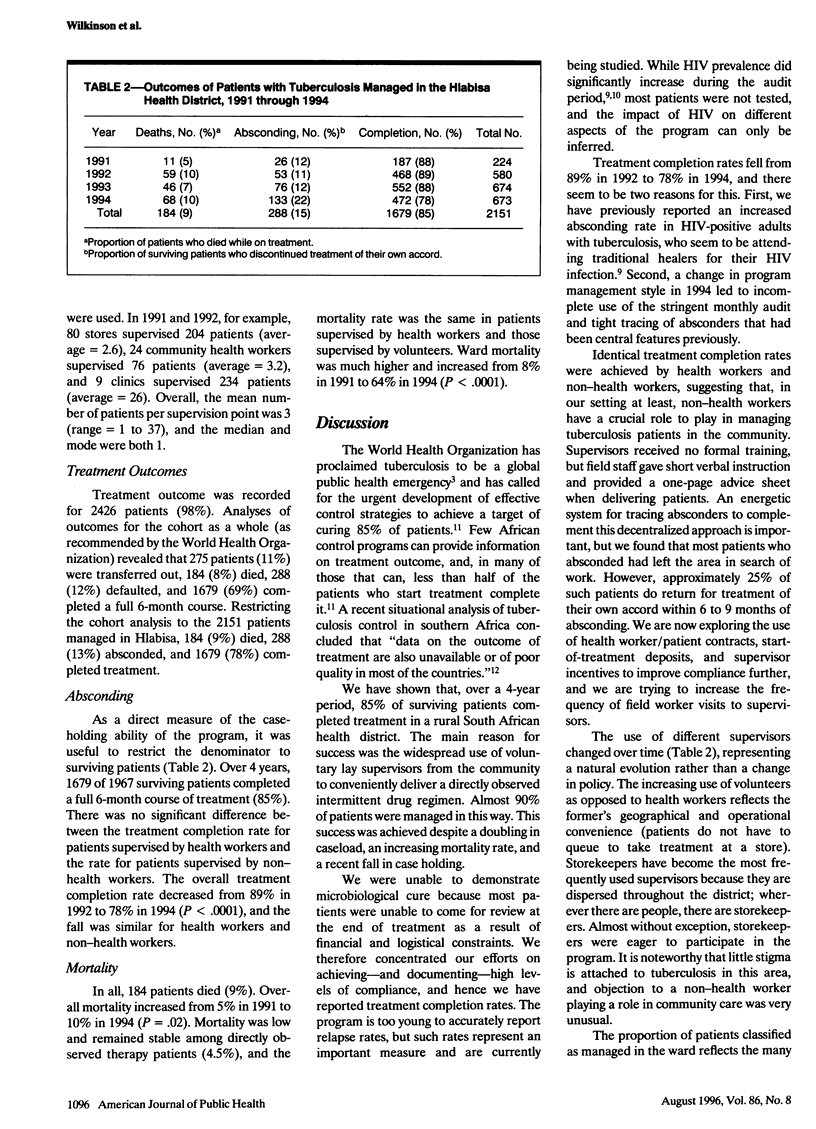

OBJECTIVES. This paper describes an audit of a community-based tuberculosis treatment program involving directly observed therapy in South Africa. METHODS. A program audit of 2473 consecutive tuberculosis patients in Hlabisa Health District, KwaZulu/Natal, South Africa, was conducted between 1991 and 1994. RESULTS. Monthly admissions increased from 34 per month in 1991 to 66 in 1994. Of 2186 patients managed in Hlabisa, 1903 (87%) received directly observed therapy. Of those receiving directly observed therapy, 1034 (55%) were supervised by volunteers; 743 (72%) of these were supervised by storekeepers. Among those patients managed locally, 1679 (85%) of 1967 surviving patients completed treatment. Completion rates for patients supervised by health workers and non-health workers were the same. Completion fell from a high of 90% in 1992 to 78% in 1994. Mortality increased from 5% in 1991 to 10% in 1994. CONCLUSIONS. Community-based directly observed therapy that uses an intermittent drug regime and volunteers as supervisors can achieve high treatment completion rates for tuberculosis, even in resource-poor settings.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Bayer R., Wilkinson D. Directly observed therapy for tuberculosis: history of an idea. Lancet. 1995 Jun 17;345(8964):1545–1548. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)91090-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies G. R., Wilkinson D., Colvin M. HIV and tuberculosis. S Afr Med J. 1996 Jan;86(1):91–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Cock K. M., Wilkinson D. Tuberculosis control in resource-poor countries: alternative approaches in the era of HIV. Lancet. 1995 Sep 9;346(8976):675–677. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)92284-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frieden T. R., Fujiwara P. I., Washko R. M., Hamburg M. A. Tuberculosis in New York City--turning the tide. N Engl J Med. 1995 Jul 27;333(4):229–233. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199507273330406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iseman M. D., Cohn D. L., Sbarbaro J. A. Directly observed treatment of tuberculosis. We can't afford not to try it. N Engl J Med. 1993 Feb 25;328(8):576–578. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199302253280811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochi A. The global tuberculosis situation and the new control strategy of the World Health Organization. Tubercle. 1991 Mar;72(1):1–6. doi: 10.1016/0041-3879(91)90017-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narain J. P., Raviglione M. C., Kochi A. HIV-associated tuberculosis in developing countries: epidemiology and strategies for prevention. Tuber Lung Dis. 1992 Dec;73(6):311–321. doi: 10.1016/0962-8479(92)90033-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudre P., ten Dam G., Kochi A. Tuberculosis: a global overview of the situation today. Bull World Health Organ. 1992;70(2):149–159. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson D. High-compliance tuberculosis treatment programme in a rural community. Lancet. 1994 Mar 12;343(8898):647–648. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)92640-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson D., Moore D. A. HIV-related tuberculosis in South Africa--clinical features and outcome. S Afr Med J. 1996 Jan;86(1):64–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]