Abstract

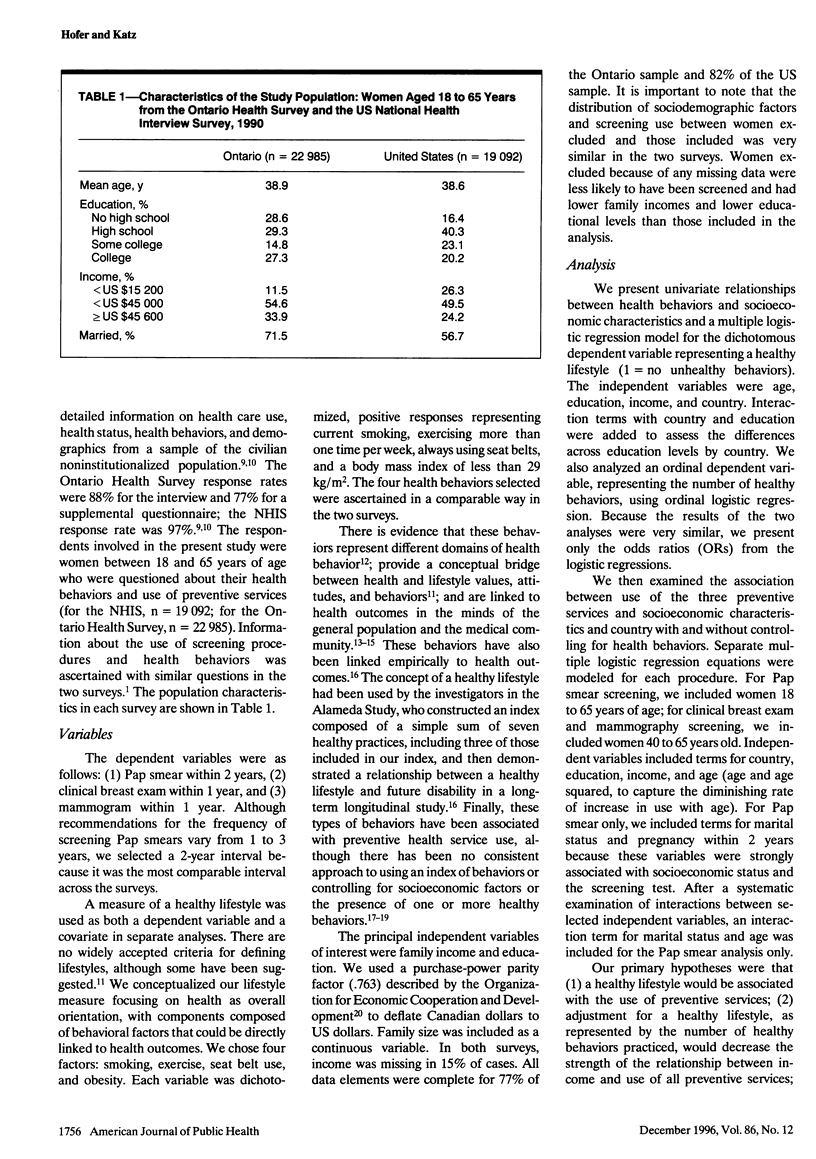

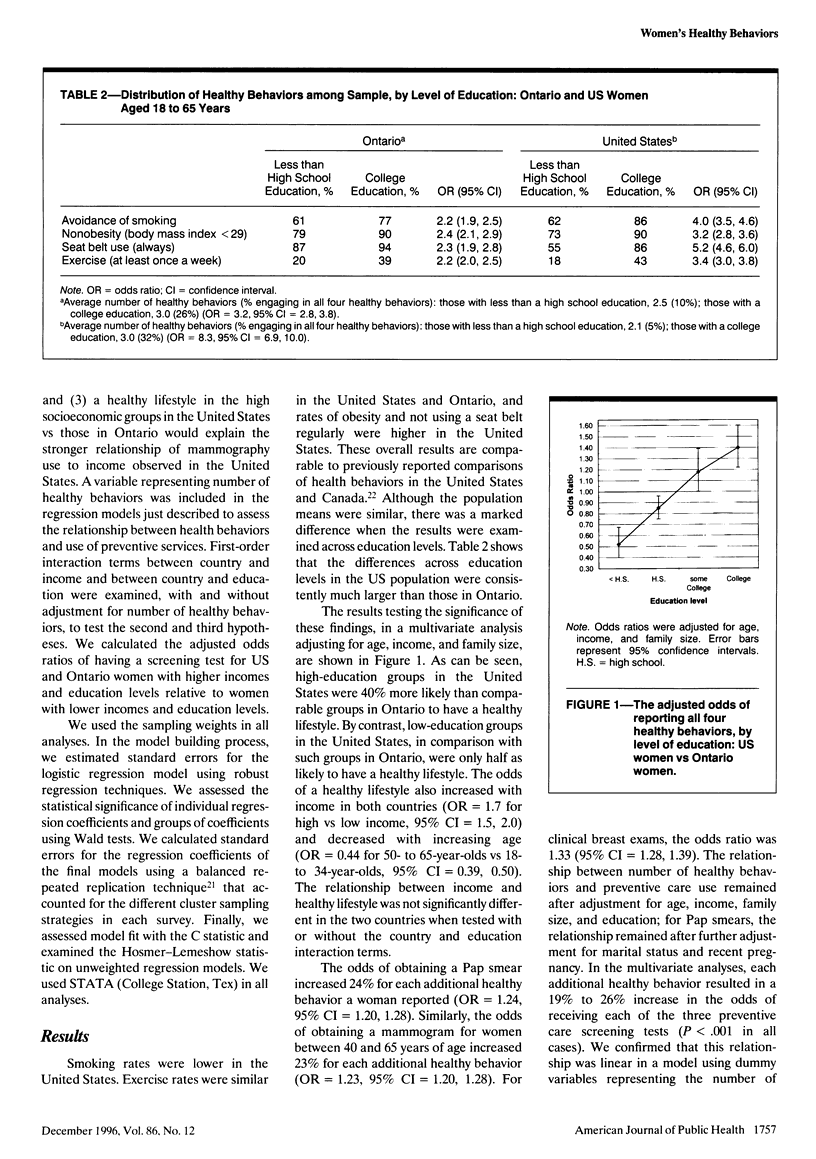

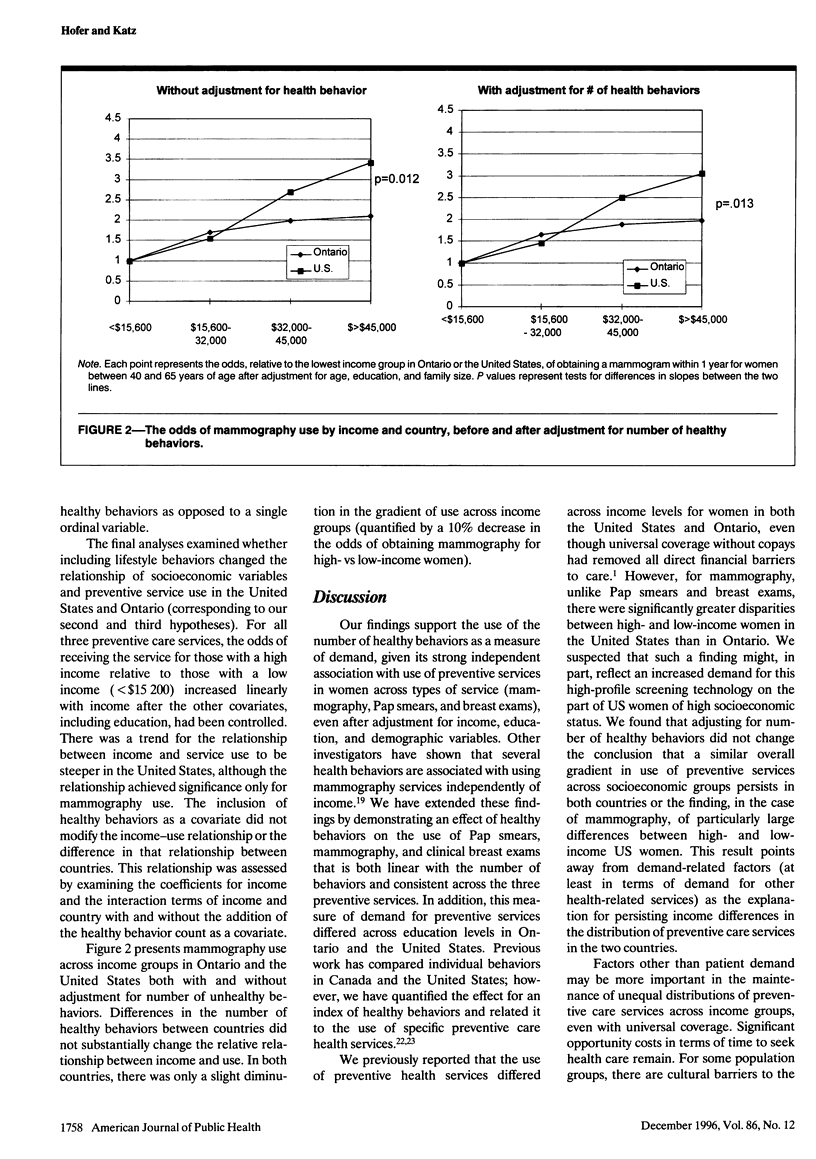

OBJECTIVES: This study examined how several healthy behaviors among women in Ontario and the United States explained (1) the use of preventive health services, (2) differences in use between socioeconomic groups, and (3) differences in use between the two health systems. METHODS: 1990 data on women from the Ontario Health Survey (n = 22,985) and the US National Health Interview Survey (n = 19,092) were analyzed. A woman who avoided smoking and obesity, used seatbelts, and regularly engaged in aerobic exercise was defined as having a healthy lifestyle. Women were considered screened if they reported a mammogram or a breast exam within the previous year or a Pap smear within 2 years. RESULTS: A healthy lifestyle was more common in the United States than Canada among more highly educated groups (odds ratio [OR] = 1.40; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.22, 1.60 for college educated) but less common in the United States for those with less than a high school education (OR = 0.52; 95% CI = 0.40, 0.67). Each additional unhealthy behavior decreased the odds of having undergone a mammogram in the previous year by 20%. However, adjusting for the number of unhealthy behaviors did not substantially change the relationship between socioeconomic status and use of preventive services. CONCLUSIONS: The number of healthy behaviors is an important measure of demand for preventive health services. This measure varies across country and socioeconomic group.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Abel T. Measuring health lifestyles in a comparative analysis: theoretical issues and empirical findings. Soc Sci Med. 1991;32(8):899–908. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90245-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aday L. A., Andersen R. M. The national profile of access to medical care: where do we stand? Am J Public Health. 1984 Dec;74(12):1331–1339. doi: 10.2105/ajph.74.12.1331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslow L., Breslow N. Health practices and disability: some evidence from Alameda County. Prev Med. 1993 Jan;22(1):86–95. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1993.1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coburn D., Pope C. R. Socioeconomic status and preventive health behavior. J Health Soc Behav. 1974 Jun;15(2):67–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cockerham W. C., Kunz G., Lueschen G. Social stratification and health lifestyles in two systems of health care delivery: a comparison of the United States and West Germany. J Health Soc Behav. 1988 Jun;29(2):113–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein F. H. The relationship of lifestyle to international trends in CHD. Int J Epidemiol. 1989;18(3 Suppl 1):S203–S209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz S. J., Hofer T. P. Socioeconomic disparities in preventive care persist despite universal coverage. Breast and cervical cancer screening in Ontario and the United States. JAMA. 1994 Aug 17;272(7):530–534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberatos P., Link B. G., Kelsey J. L. The measurement of social class in epidemiology. Epidemiol Rev. 1988;10:87–121. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a036030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmot M. G., Smith G. D., Stansfeld S., Patel C., North F., Head J., White I., Brunner E., Feeney A. Health inequalities among British civil servants: the Whitehall II study. Lancet. 1991 Jun 8;337(8754):1387–1393. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)93068-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millar W. J., Stephens T. Social status and health risks in Canadian adults: 1985 and 1991. Health Rep. 1993;5(2):143–156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millar W. A trend to a healthier lifestyle. Health Rep. 1991;3(4):363–370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman S. A., Talbott E. O., Kuller L. H., Krampe B. R., Stolley P. D. Demographic, psychosocial, and medical correlates of Pap testing: a literature review. Am J Prev Med. 1991 Jul-Aug;7(4):219–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakowski W., Rimer B. K., Bryant S. A. Integrating behavior and intention regarding mammography by respondents in the 1990 National Health Interview Survey of Health Promotion and Disease Prevention. Public Health Rep. 1993 Sep-Oct;108(5):605–624. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Retchin S. M., Wells J. A., Valleron A. J., Albrecht G. L. Health behavior changes in the United States, the United Kingdom, and France. J Gen Intern Med. 1992 Nov-Dec;7(6):615–622. doi: 10.1007/BF02599200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rimer B. K., Trock B., Engstrom P. F., Lerman C., King E. Why do some women get regular mammograms? Am J Prev Med. 1991 Mar-Apr;7(2):69–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenborn C. A., Stephens T. Health promotion in the United States and Canada: smoking, exercise, and other health-related behaviors. Am J Public Health. 1988 Aug;78(8):983–984. doi: 10.2105/ajph.78.8.983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobal J., Revicki D., DeForge B. R. Patterns of interrelations among health-promotion behaviors. Am J Prev Med. 1992 Nov-Dec;8(6):351–359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steptoe A., Wardle J. Cognitive predictors of health behaviour in contrasting regions of Europe. Br J Clin Psychol. 1992 Nov;31(Pt 4):485–502. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1992.tb01021.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein N. D. Testing four competing theories of health-protective behavior. Health Psychol. 1993 Jul;12(4):324–333. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.12.4.324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]