Abstract

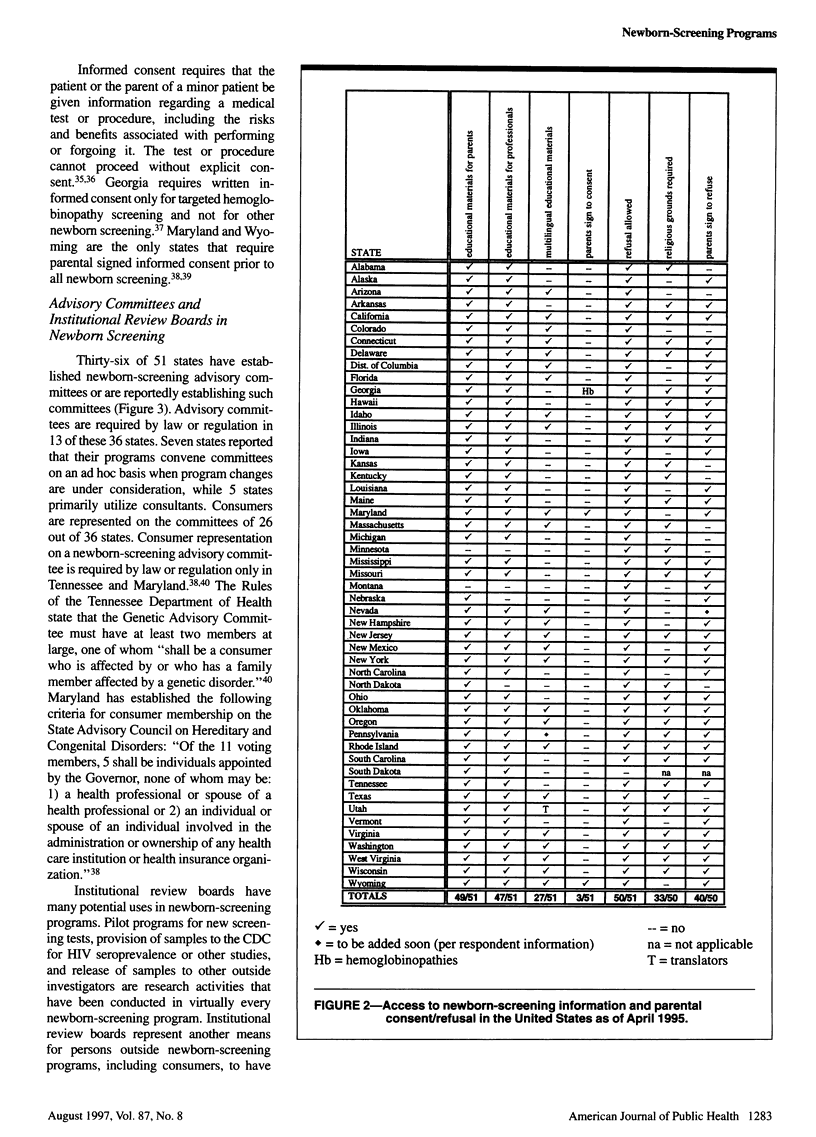

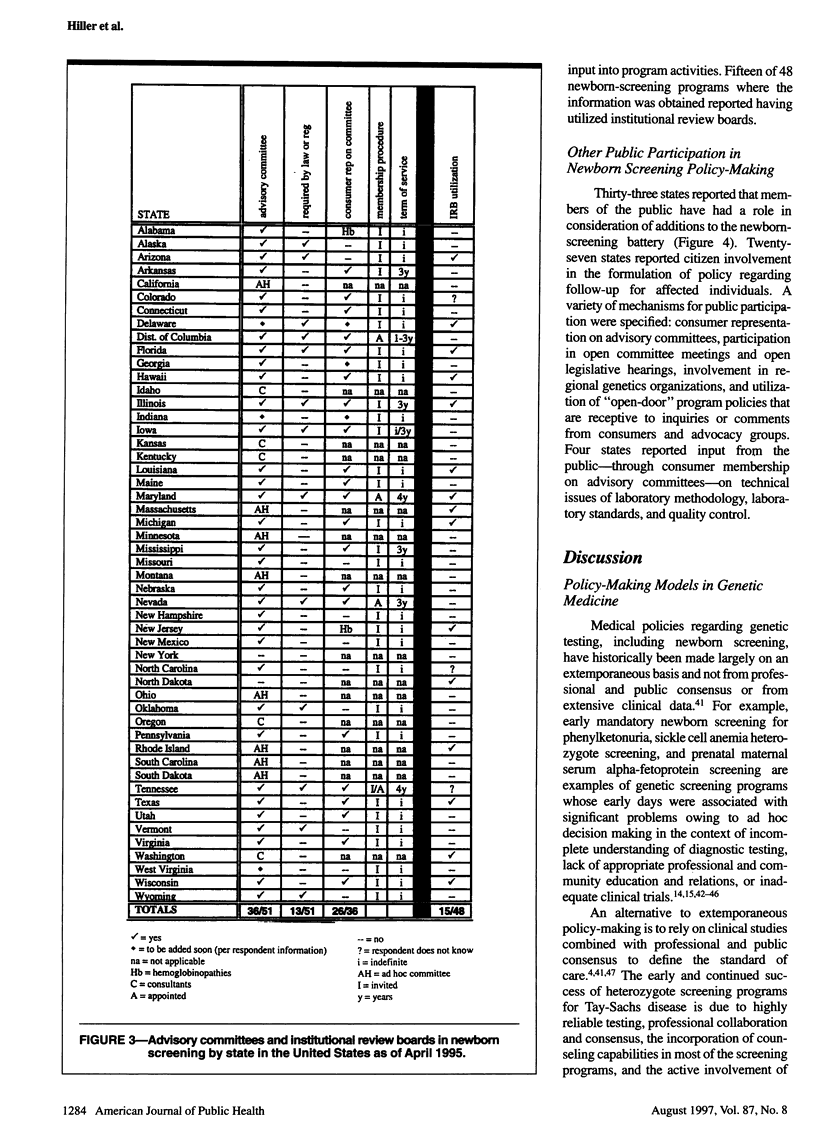

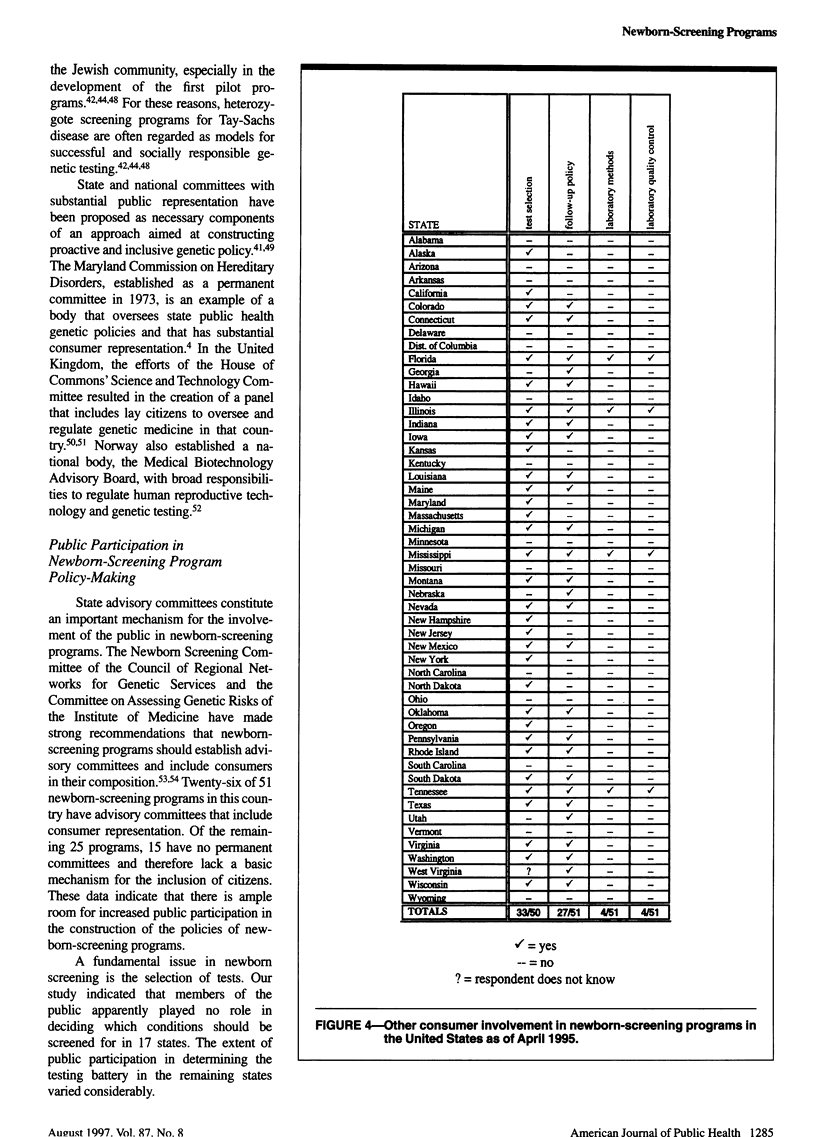

OBJECTIVES: State newborn-screening programs collectively administer the largest genetic-testing initiative in the United States. We sought to assess public involvement in formulating and implementing medical policy in this important area of genetic medicine. METHODS: We surveyed all state newborn-screening programs to ascertain the screening tests performed, the mechanisms and extent of public participation, parental access to information, and policies addressing parental consent or refusal of newborn screening. We also reviewed the laws and regulations of each state pertaining to newborn screening. RESULTS: Only 26 of the 51 state newborn-screening programs reported having advisory committees that include consumer representation. Fifteen states reported having used institutional review boards, another venue for public input. The rights and roles of parents vary markedly among newborn-screening programs in terms of the type and availability of screening information as well as consent-refusal and follow-up policies. CONCLUSIONS: There is clear potential for greater public participation in newborn-screening policy-making. Greater public participation would result in more representative policy-making and could enhance the quality of services provided by newborn-screening programs.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Annas G. J. Mandatory PKU screening: the other side of the looking glass. Am J Public Health. 1982 Dec;72(12):1401–1403. doi: 10.2105/ajph.72.12.1401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody D. S., Miller S. M., Lerman C. E., Smith D. G., Caputo G. C. Patient perception of involvement in medical care: relationship to illness attitudes and outcomes. J Gen Intern Med. 1989 Nov-Dec;4(6):506–511. doi: 10.1007/BF02599549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casper B. M. Technology policy and democracy. Science. 1976 Oct 1;194(4260):29–35. doi: 10.1126/science.959841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavkin W. Preventing AIDS, targeting women. Health PAC Bull. 1990 Spring;20(1):19–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clayton E. W. Issues in state newborn screening programs. Pediatrics. 1992 Oct;90(4):641–646. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clayton Ellen Wright. Screening and treatment of newborns. Houst Law Rev. 1992 Spring;29(1):85–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faden R. R., Holtzman N. A., Chwalow A. J. Parental rights, child welfare, and public health: the case of PKU screening. Am J Public Health. 1982 Dec;72(12):1396–1400. doi: 10.2105/ajph.72.12.1396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fost N. Ethical implications of screening asymptomatic individuals. FASEB J. 1992 Jul;6(10):2813–2817. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.6.10.1634044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield S., Kaplan S. H., Ware J. E., Jr, Yano E. M., Frank H. J. Patients' participation in medical care: effects on blood sugar control and quality of life in diabetes. J Gen Intern Med. 1988 Sep-Oct;3(5):448–457. doi: 10.1007/BF02595921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heymann S. J. Patients in research: not just subjects, but partners. Science. 1995 Aug 11;269(5225):797–798. doi: 10.1126/science.7638595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holman Halsted R., Dutton Diana B. A case for public participation in science policy formation and practice. South Calif Law Rev. 1978 Sep;51(6):1505–1534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaback M., Lim-Steele J., Dabholkar D., Brown D., Levy N., Zeiger K. Tay-Sachs disease--carrier screening, prenatal diagnosis, and the molecular era. An international perspective, 1970 to 1993. The International TSD Data Collection Network. JAMA. 1993 Nov 17;270(19):2307–2315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lappé Marc, Martin Patricia A. The place of the public in the conduct of science. South Calif Law Rev. 1978 Sep;51(6):1535–1554. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myklebost O. First for biotech. Nature. 1996 Nov 21;384(6606):208–208. doi: 10.1038/384208b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natowicz M. R., Alper J. S. Genetic screening: triumphs, problems, and controversies. J Public Health Policy. 1991 Winter;12(4):475–491. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichel W., Franch M. S., Solon J. Survey research guiding public policy making in Maryland: the case of Alzheimer's disease and related disorders. Exp Gerontol. 1986;21(4-5):439–448. doi: 10.1016/0531-5565(86)90049-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodwin M. A. Patient accountability and quality of care: lessons from medical consumerism and the patients' rights, women's health and disability rights movements. Am J Law Med. 1994;20(1-2):147–167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone Richard. Animal research bills threaten Polish science. Science. 1995 Jul 21;269(5222):291–291. doi: 10.1126/science.11644752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitten C. F. Sickle-cell programming--an imperiled promise. N Engl J Med. 1973 Feb 8;288(6):318–319. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197302082880612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilfond B. S., Nolan K. National policy development for the clinical application of genetic diagnostic technologies. Lessons from cystic fibrosis. JAMA. 1993 Dec 22;270(24):2948–2954. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]