Abstract

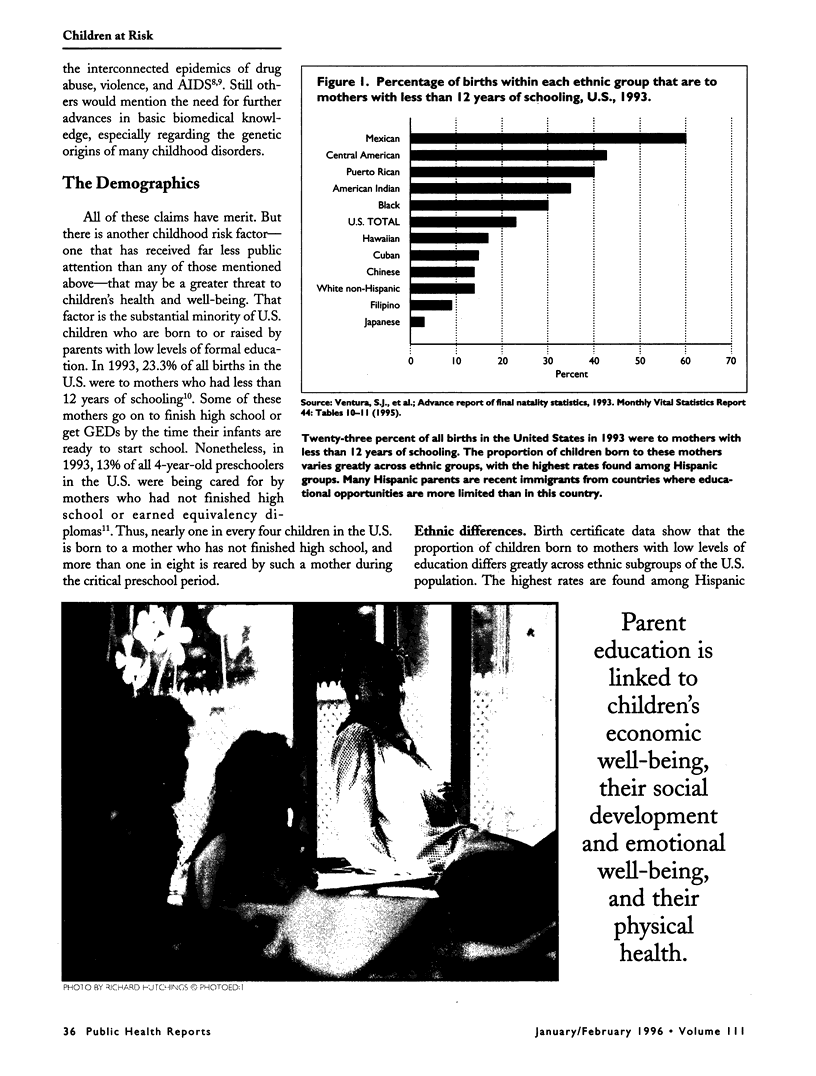

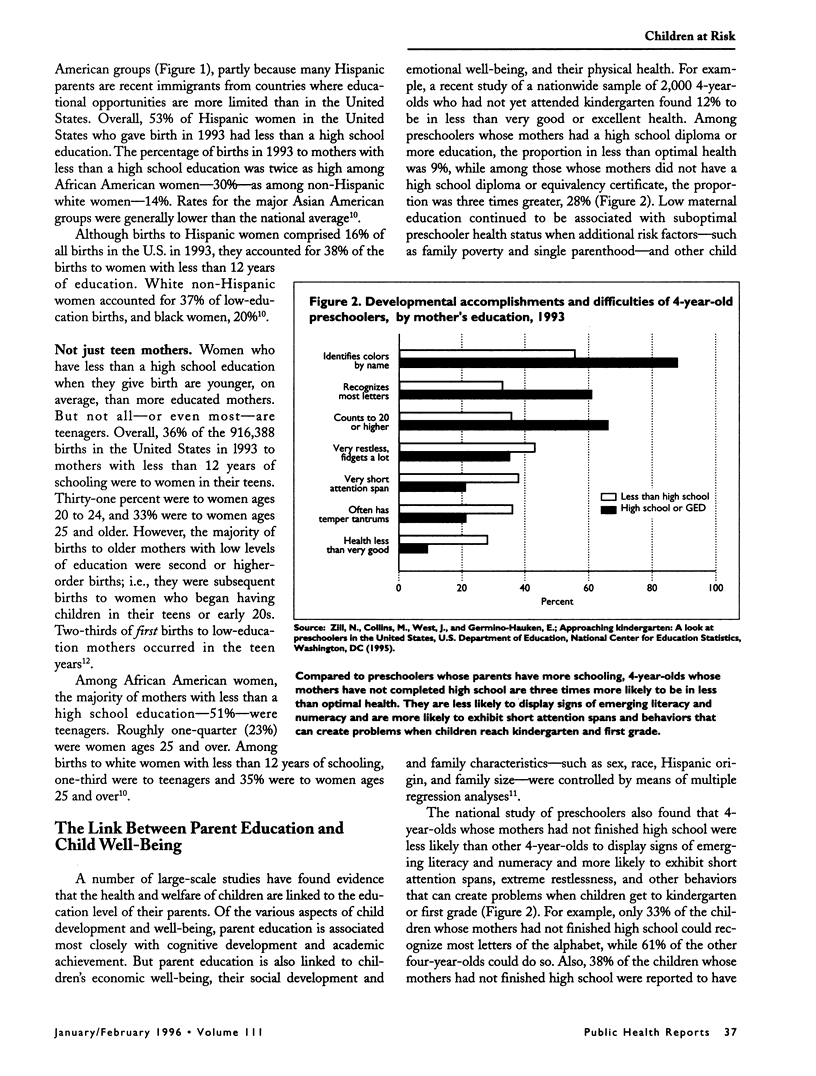

Nearly one in every four children in the United States is born to a mother who has not finished high school, and more than one in eight is reared by such a mother during the critical preschool period. Large-scale studies show that the health and welfare of children are linked to the education level of their parents, with parent education often being a stronger predictor of child well-being than family income, single parenthood, or family size. Higher parent education levels make it more likely that children will receive adequate medical care and that their daily environments will be protected and responsive to their needs. Average parent education levels have risen over the last 30 years, but progress has slowed because of high rates of immigration from countries with lower education standards and the tendency of more advantaged women to have children later than less advantaged women. The education system and community organizations must provide young people who are not doing well in school with positive alternatives to low- education, high-risk parenthood. Health care providers should be proactive, teaching parents with few resources how best to promote their children's growth and development. The changing global economy makes it more important than ever that current and future generations of children are reared by parents who have adequate skills and training to be competent members of society and effective and responsible parents.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Aber J. L., Brooks-Gunn J., Maynard R. A. Effects of welfare reform on teenage parents and their children. Future Child. 1995 Summer-Fall;5(2):53–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aber J. L., Brooks-Gunn J., Maynard R. A. Effects of welfare reform on teenage parents and their children. Future Child. 1995 Summer-Fall;5(2):53–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair J. F., Hein K. K. Public policy implications of HIV/AIDS in adolescents. Future Child. 1994 Winter;4(3):73–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham P. J., Hahn B. A. The changing American family: implications for children's health insurance coverage and the use of ambulatory care services. Future Child. 1994 Winter;4(3):24–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earls F. J. Violence and today's youth. Future Child. 1994 Winter;4(3):4–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forrest J. D., Singh S. The sexual and reproductive behavior of American women, 1982-1988. Fam Plann Perspect. 1990 Sep-Oct;22(5):206–214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forrest J. D., Singh S. The sexual and reproductive behavior of American women, 1982-1988. Fam Plann Perspect. 1990 Sep-Oct;22(5):206–214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman R. E. Tracking 1990 objectives for injury prevention with 1985 NHIS findings. Public Health Rep. 1986 Nov-Dec;101(6):581–586. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landrigan P. J., Carlson J. E. Environmental policy and children's health. Future Child. 1995 Summer-Fall;5(2):34–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson M. D., Jr Socioeconomic status and childhood mortality in North Carolina. Am J Public Health. 1992 Aug;82(8):1131–1133. doi: 10.2105/ajph.82.8.1131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]