Abstract

Background

The N-acetylation of L-glutamate is regarded as a universal metabolic strategy to commit glutamate towards arginine biosynthesis. Until recently, this reaction was thought to be catalyzed by either of two enzymes: (i) the classical N-acetylglutamate synthase (NAGS, gene argA) first characterized in Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa several decades ago and also present in vertebrates, or (ii) the bifunctional version of ornithine acetyltransferase (OAT, gene argJ) present in Bacteria, Archaea and many Eukaryotes. This paper focuses on a new and surprising aspect of glutamate acetylation. We recently showed that in Moritella abyssi and M. profunda, two marine gamma proteobacteria, the gene for the last enzyme in arginine biosynthesis (argH) is fused to a short sequence that corresponds to the C-terminal, N-acetyltransferase-encoding domain of NAGS and is able to complement an argA mutant of E. coli. Very recently, other authors identified in Mycobacterium tuberculosis an independent gene corresponding to this short C-terminal domain and coding for a new type of NAGS. We have investigated the two prokaryotic Domains for patterns of gene-enzyme relationships in the first committed step of arginine biosynthesis.

Results

The argH-A fusion, designated argH(A), and discovered in Moritella was found to be present in (and confined to) marine gamma proteobacteria of the Alteromonas- and Vibrio-like group. Most of them have a classical NAGS with the exception of Idiomarina loihiensis and Pseudoalteromonas haloplanktis which nevertheless can grow in the absence of arginine and therefore appear to rely on the arg(A) sequence for arginine biosynthesis. Screening prokaryotic genomes for virtual argH-X 'fusions' where X stands for a homologue of arg(A), we retrieved a large number of Bacteria and several Archaea, all of them devoid of a classical NAGS. In the case of Thermus thermophilus and Deinococcus radiodurans, the arg(A)-like sequence clusters with argH in an operon-like fashion. In this group of sequences, we find the short novel NAGS of the type identified in M. tuberculosis. Among these organisms, at least Thermus, Mycobacterium and Streptomyces species appear to rely on this short NAGS version for arginine biosynthesis.

Conclusion

The gene-enzyme relationship for the first committed step of arginine biosynthesis should now be considered in a new perspective. In addition to bifunctional OAT, nature appears to implement at least three alternatives for the acetylation of glutamate. It is possible to propose evolutionary relationships between them starting from the same ancestral N-acetyltransferase domain. In M. tuberculosis and many other bacteria, this domain evolved as an independent enzyme, whereas it fused either with a carbamate kinase fold to give the classical NAGS (as in E. coli) or with argH as in marine gamma proteobacteria. Moreover, there is an urgent need to clarify the current nomenclature since the same gene name argA has been used to designate structurally different entities. Clarifying the confusion would help to prevent erroneous genomic annotation.

Background

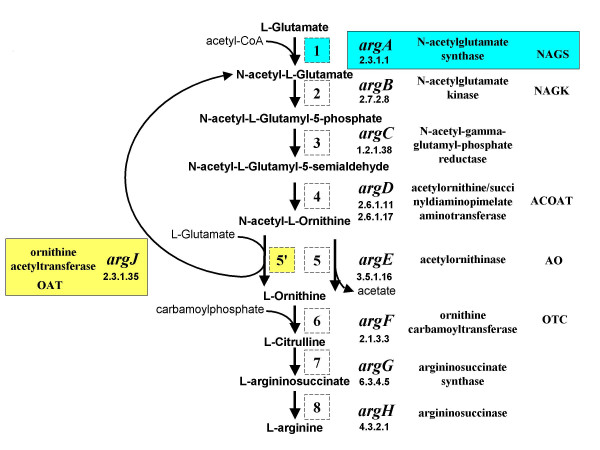

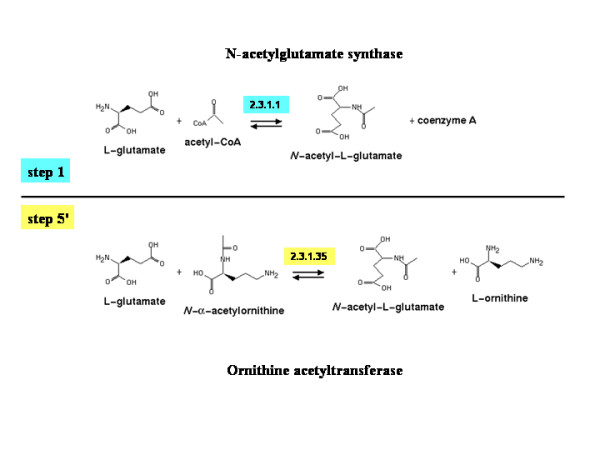

Until recently the de novo arginine biosynthetic pathway (Figs. 1A and 1B) was thought to conform to a simple type of one gene-one enzyme relationship even if it had been known for a long time that the fifth step, the conversion of N-α-acetyl-L-ornithine into L-ornithine, could be catalyzed by different enzymes. An ornithine acetyltransferase (OAT, ArgJ; EC 2.3.1.35) recycles the transfer of the acetyl group from acetylornithine to glutamate in most organisms (Bacteria, Archaea and Eukaryotes), whereas an acetylornithinase (AO; ArgE; EC 3.5.1.16) splits the acetyl group from acetylornithine in enteric and vibrio-like bacteria as well as in Xylella fastidiosa, Xanthomonas campestris, Myxococcus xanthus and, possibly, the crenarchaeon Sulfolobus solfataricus (see [1] and [2] for reviews).

Figure 1.

The de novo arginine biosynthetic pathway. Outline of the pathway; for each step (labeled by a number in a square) the following features are indicated: gene name, EC number, enzyme name and its abbreviation.

Three findings concerning the status of acetylated intermediates in arginine synthesis and the enzymes involved in their genesis have rendered this picture more intricate. (i) In X. campestris and Bacteroides fragilis, an acetylornithine carbamoyltransferase was found to replace the canonical ornithine carbamoyltransferase (OTC; ArgF; EC 2.1.3.3) [3,4]; (ii) In Bacillus stearothermophilus, and Thermotoga neapolitana, OAT is bifunctional: in addition to recycling the acetyl group it also synthesizes N-acetylglutamate directly from acetylCoA and glutamate, the reaction catalyzed by N-acetylglutamate synthase (NAGS; ArgA; EC 2.3.1.1) [5]. Since the genomes of their closely related organisms, B. subtilis and T. maritima respectively, appear to lack a NAGS, the question arises whether some organisms use a bifunctional OAT instead of a NAGS to synthesize acetylglutamate [[5] and references therein, [6]]. (iii) Two novel species of marine gamma proteobacteria belonging to the genus Moritella, display an unusual gene structure for argininosuccinase (ArgH; EC 4.3.2.1), the last enzyme of the pathway: argH gene is extended by a ± 170 codon-long stretch which can complement E. coli mutants deficient in NAGS [7,8]. This new gene was called argH(A). The (A) sequence is homologous to the C-terminal domain of Escherichia coli NAGS: this domain contains an acetylCoA N-acyltransferase fold (see [1]) whereas the N-terminal domain of E. coli NAGS presents striking similarities with the carbamate kinase-like domain of N-acetylglutamate kinase (NAGK, EC 2.7.2.8., ArgB) [9], the next enzyme in the pathway. The recent explosion of genomic data has enabled us to find other organisms endowed with the argH(A) fusion as well as many instances where a sequence homologous to arg(A) is not fused to argH. Moreover, as this work was in progress, a new functional ArgA protein (gene Rv2747) has been characterized in Mycobacterium tuberculosis [10]. Interestingly, the cognate gene is found to be homologous to Moritella arg(A). These findings have important implications regarding the formation of acetylated intermediates in arginine biosynthesis and the evolution of the cognate enzymes.

Results and Discussion

Occurrence of the argH(A) gene

While studying arginine biosynthetic genes in two vibrio-like strains (later characterized as novel psychropiezophilic Moritella species M. abyssi and M. profunda [8]) we found most arg genes clustered into a divergent operon-like structure composed of two wings: a leftward one comprising the sole argE gene and a rightward one argCBFGH(A) where argH is extended by a ± 170-long codon stretch, in translational continuity. This extension was shown to complement an E. coli auxotroph deficient in NAGS [7], demonstrating that it encodes an ArgA-like activity (EC 2.3.1.1).

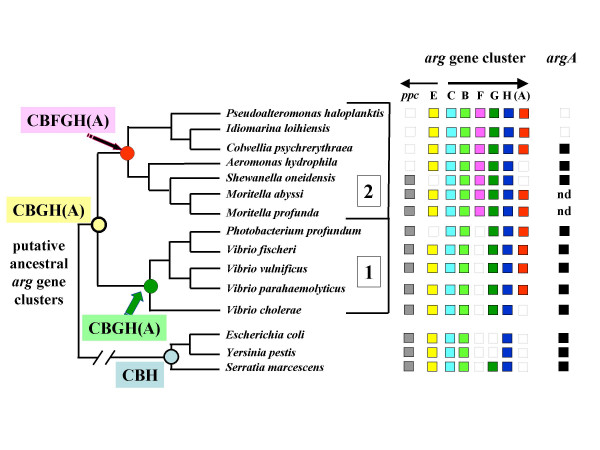

We searched for the presence of the argH(A) fusion gene homologues in completely sequenced microbial genomes. Blast analyses identified nine bacteria that are phylogenetically related to Moritella. This is shown in Fig. 3, which combines a simplified and partial version of an extensive 16S rRNA tree for Alteromonas and Vibrio-like bacteria [11] with genomic information about the structure of the arg gene cluster. Most of these organisms display the divergent pattern characteristic of vibrio-like and enteric bacteria, which contrasts with the more scattered pattern encountered in other branches of the gamma proteobacteria [2,7]. There are differences: the shorter version clusters argE with argCBH, as in E. coli and Yersinia pestis, whereas the right wing is longer in several other bacteria. Thus, argCBGH was probably present already in the common ancestor to clades 1 and 2, and argCBFGH in the ancestor to clade 2. Note that argE is not clustered with other arg genes in Shewanella oneidensis and Photobacterium profundum.

Figure 3.

Phylogenetic relationships of species harbouring ArgH(A) fusions. A simplified version of the 16S rRNA phylogenetic tree of Alteromonas- and Vibrio-like bacteria reconstructed by Ivanova et al.[11] has been drawn and enriched with the following information. On the right-hand side, available genomic information concerning arg genes; ppc refers to the gene for phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase, adjacent to argE in many of these organisms; nd: not determined. On the left-hand side, the putative content of the ancestral arg gene clusters are indicated for each deep node of this tree.

In conclusion:

(i) argH(A) appears to be restricted to this particular group of marine Bacteria. It is noticeable that V. cholerae, which is not a marine organism, does not have argH(A) whereas the three marine Vibrio species do: V. fischeri, V. vulnificus and V. parahaemolyticus. This pattern suggests that the presence of argH(A) is the result of orthologous transfer in diverging lines of descent sharing a common habitat (the sea), perhaps accompanied by some lateral transfer among them as discussed below. Fig 3 suggests that the H(A) fusion occurred in an ancestor common to clades 1 and 2, but this can not be ascertained without an extensive search among the numerous members of this group, in particular among different Idiomarina and Pseudoalteromonas species, as well as in the genera branching early on this tree.

(ii) No correlation appears to exist between the presence of argH(A) and either psychrophily or piezophily. Indeed argH(A) was found among mesophiles (V. fischeri, V. vulnificus, V. parahaemolyticus), psychrophiles (Colwiella psychrerythraea, Pseudoalteromonas haloplanktis), psychro-piezophiles (P. profundum, M. abyssi, M. profunda) and meso-piezophiles (Idiomarina loihiensis). As the cardinal temperatures and hydrostatic pressures of these closely related organisms actually overlap, lateral transfer among them seems feasible even if the reality of the phenomenon is beyond experimental proof.

(iii) Sequences homologous to the full E. coli argA gene were found in several of the organisms harboring the H(A) fusion but not in I. loihiensis and P. haloplanktis (for M. abyssi and M. profunda, their genomes have not yet been sequenced). In I. loihiensis and P. haloplanktis, the (A) sequence therefore does not appear to be functionally redundant, which in turn suggests that these organisms, which can grow in absence of arginine [12,13], depend exclusively on domain (A) for the first step of arginine biosynthesis.

Origin of argH(A)

The data suggest that argH(A) results from a fusion that occurred between argH and a gene coding for an acetyltransferase able to acetylate L-glutamate in the N- position. The fusion could have been selected for in an organism devoid of a canonical NAGS, such as I. loihiensis and P. haloplanktis, perhaps as the result of gene loss, or it may reflect a more primordial event. Interestingly, in I. loihiensis, the genes of the argCBFGH(A) cluster are tightly coupled, either overlapping by 3 nt (argC and B, argF and G), separated by 3 nt (argB and F) or by 4 (argG and H). This arrangement suggests that, at the time the fusion originated, the capacity to derepress the recruited acetyltransferase from the rightward promoter of the operon may have been essential and actually explains why this fusion took place. In keeping with this hypothesis, the genome of I. loihiensis and P. haloplanktis do contain a sequence homologous to the E. coli argR regulatory gene.

Occurrence of arg(A)-like sequences with putative function in other organisms

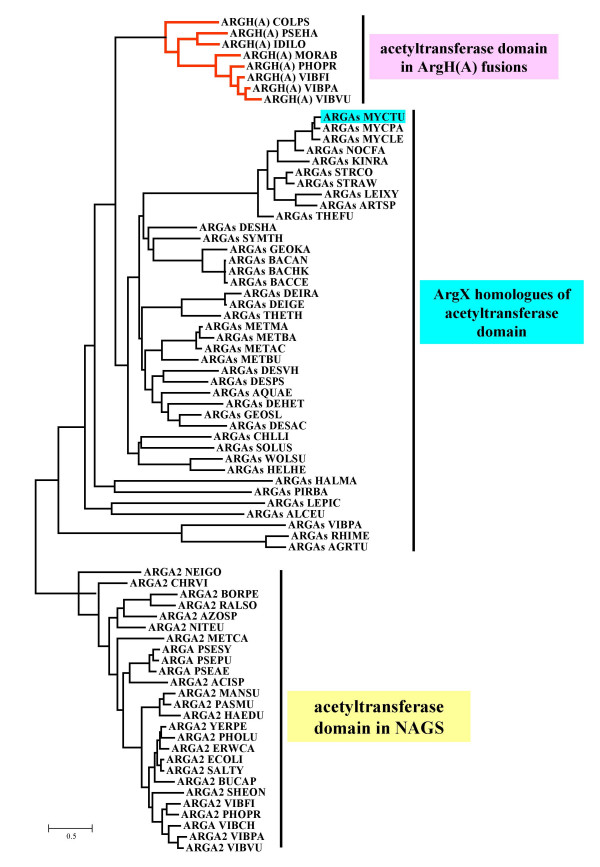

If there were an N-acetyltransferase gene susceptible to recruitment in a bacterium related to Idiomarina, it would probably be present in many genomes. In order to test this hypothesis we employed a two-step strategy. First, we screened prokaryotes for the presence of acetyltransferase genes similar to the arg(A) sequence of M. abyssi (see Methods). Fourty-four completely sequenced genomes have homologous genes that were annotated as coding for either a hypothetical protein or a putative acetyltransferase. These argX genes were aligned with the arg(A) sequences and with the homologous acetyltransferase domain of NAGS. A phylogenetic tree was computed from this alignment using a maximum likelihood approach and rooted with the acetyltransferase domain of classical NAGS enzymes. Fig. 4 shows that the arg(A) sequences form a monophyletic group which share a common ancestor with a large group containing the short NAGS version recently found in M. tuberculosis [10]. This tree also shows the complex relationships between the different paralogous argA-like sequences. For instance, V. parahaemolyticus contains three related sequences: the fused arg(A), an argX that is a remote paralogue to this arg(A), and the classical argA (NAGS). It is not clear what are the respective roles of these different paralogues in cell metabolism.

Figure 4.

Phylogenetic tree of the arg(A) homologues. The sequences have been collected, multiply aligned and used to reconstruct an evolutionary tree as described in Methods. The tree has been rooted using the acetyltransferase domain of NAGS sequences as an outgroup (subtree indicated with yellow color). The two other subtrees corresponding to the Arg(A) and ArgX sequences are indicated with pink and blue colors, respectively. Species names are according to SwissProt conventions (the detailed list is shown in Table 1).

Furthermore, we fused these arg(A)-like sequences in silico with argH sequences from the same organism in order to build so-called argHX sequences. Since argH is in the the last step of the pathway, and the (A) determinant in the first one, we focused the search on organisms presumed to possess the whole pathway and, took into account any structural and/or functional significance of the association of the two determinants. All 26 species found using this approach form a homogeneous group presenting the following features: (i) they do not possess a multidomain homologue of a NAGS protein, (ii) they contain an ornithine acetyltransferase (ArgJ) and (iii) they lack an acetylornithinase gene (ArgE). Thus, these 26 species should use an alternative to NAGS in order to acetylate glutamate and are presumed to recycle the transfer of the acetyl group from acetylornithine to glutamate. In contrast, the species retrieved in the first step of the screening, before implementing the virtual fusion approach, form a wider and less homogeneous group (Fig. 4), where NAGS and/or ArgE can be found. This suggests that the virtual fusion approach identifies a functionally significant group.

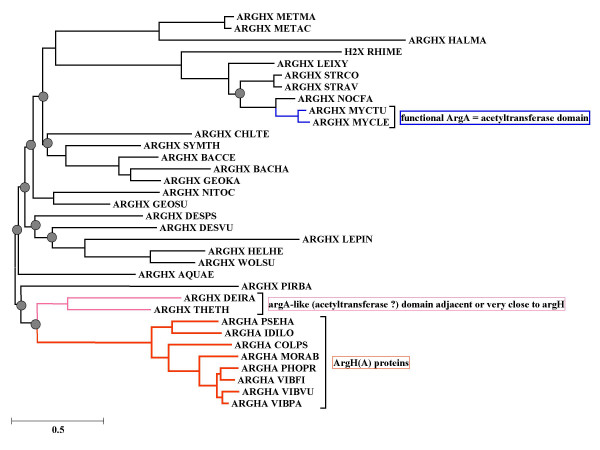

The different, virtual argHX sequences were further aligned with their homologues argH(A) and an evolutionary tree was reconstructed using a maximum likelihood approach (Fig 5). Note that the large size of argH (more than 420 residues) and its relatively high degree of conservation increase the overall similarities between the argH(A) fusions. This could contribute to the topological differences between the trees in Figs. 4 and 5. The phylogenetic analysis of the fusion approach displays intriguing aspects:

Figure 5.

Phylogenetic tree of the ArgH(A) and ArgHX fusions. The sequences have been collected, multiply aligned and used to reconstruct an evolutionary tree as described in Methods. The grey circles indicate the bootstrap values for the deep nodes which are less than 60%. Species names are according to SwissProt conventions (the detailed list is shown in Table 1).

i. The argH(A) fusions form a monophyletic group branching close to homologous sequences present in the genomes of both Thermus and Deinococcus, two phylogenetically related organisms. The two groups join at a node position where the bootstrap value is less than 60 %, but it is remarkable that the Thermus and Deinococcus sequences (annotated as homologues of argH and a putative acetyltransferase gene), are actually adjacent, suggesting that together they play the role of a functional analogue of argH(A). T. thermophilus argH (which overlaps argG by 10 nt at the proximal end) and the putative acetyltransferase gene are separated by only 2 nt, strongly suggesting that the Thermus arg(A)-like sequence is part of an argGH(A) operon in the arginine regulon of this organism [14]. In D. radiodurans the situation is similar but more complex: no less than three putative acetyltransferase genes are adjacent to argG (the first one separated by only 2 nt) while argH is very closely linked to another three putative acetyltransferase genes; of these three it is the last one (Q9RWI5_DEIRA Hypothetical protein DR0683) that is retrieved by our homology search.

ii. The other part of the tree contains various prokaryotic species including mesophilic Archaea. Clustering with these Archaea, we note a clade of Actinobacteria including M. tuberculosis. This is highly significant since the M. tuberculosis sequence was shown tocode for an enzyme whose functional characterization was reported while this paper was being prepared for publication: it displays acetylglutamate synthetase activity [10] and is required for the growth of its host as shown by previous high-density mutagenesis [15].

An essential question is whether any other of these 26 prokaryotes harboring an arg(A)-like sequence actually depend on it for acetylation of glutamate in vivo. We know (see above) that the complete sequence of their genome lacks a classical NAGS. The presumption would be even stronger if these species possessed a monofunctional OAT, and were thus unable to acetylate glutamate with acetyl-CoA [5,16,17]. Currently, T. thermophilus and Streptomyces coelicolor fulfill this second criterium [ibid, [18]]. The (A)-like sequence of T. thermophilus moreover appears co-regulated with the argGH cluster. It is not known whether M. tuberculosis OAT is monofunctional, but the fact that the arg(A)-like sequence of this organism was shown to be essential by transposon-mediated inactivation [15] actually suggests that it is. Since it is not yet possible to predict in silico whether a particular OAT is bifunctional [19], biochemical evidence is needed to decide which of the other microorganisms actually depend on their arg(A)-like sequence for arginine biosynthesis.

Comparative analysis of putative glutamate N-acetyltransferases

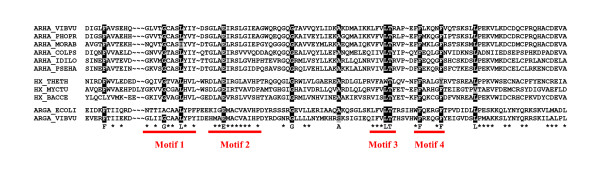

The polypeptides encoded by the fused arg(A) sequences, their X homologues and the C-terminal domain of ArgA (NAGS) belong to the vast superfamily of GNC5-N-acetyltransferases (GNAT), all using acetylCoA as common acetyl donor. Multiple alignment of these three categories of homologous sequences (Fig. 6) indicates good conservation of the four motifs which were previously identified by comparing numerous members of this superfamily [[20,21] and references therein]. Most GNAT acetyltransferases, including NAGS, proceed by a sequential mechanism, i.e. form a ternary complex of enzyme, acetylCoA and specific substrate, and not by a ping-pong mechanism involving the formation of an acetylthioenzyme intermediate between acetylCoA and an active cysteine [21,22]. In keeping with these observations, there is no strictly conserved cysteine among the sequences reported in Fig.6. More accurate prediction of catalytic residues is difficult without a NAGS 3D-structure, in particular as regards the glutamate binding site. The fact that Moritella arg(A) complements an NAGS-inactivated mutant of E. coli [7] and that pure M. tuberculosis ArgA acetylates glutamate in vitro [10] confirms that such a site is present in these proteins even though their sequence corresponds only to the C-terminal domain of classical NAGS. It is possible that the short version of NAGS has to be associated with another protein in order to bind glutamate efficiently, which makes attempts at site prediction premature without further empirical testing.

Figure 6.

Conserved motifs in putative glutamate N-acetyltransferases. The homologues to the (A) domain of ArgH(A) of M. abyssi and belonging to six ArgH(A), three ArgHX and two ArgA proteins have been multiply aligned and edited in BioEdit software [32]. A consensus sequence has been computed. Very strongly conserved residues(letters) and moderately conserved ones (stars) are indicated. The four motifs containing the residues identified by comparative analysis of N-acetyltransferases which use acetylCoA as donor of the acetyl group [20] and references therein] are underlined by thick lines and numbered. Species names are according to SwissProt conventions.

Conclusion

The discovery of a novel type of biosynthetic arg locus, coding for a classical argininosuccinase ArgH fused with a putative N-acetyltransferase able to complement an argA deficiency was extended by genomic analysis to a group of phylogenetically and ecologically related marine gamma proteobacteria. The case of I. loihiensis [12] and P. haloplanktis [23] is particularly significant from the functional point of view since the cognate genomes do not appear to contain a genuine argA sequence and the organisms are nevertheless arginine-independent, indicating that they depend on Arg(A) for arginine biosynthesis. Note there is widespread occurrence of sequences homologous to arg(A) in organisms lacking a classical NAGS (Fig. 5), including instances (Thermus and Deinococcus) where the sequence is adjacent-to, and coexpressed with argH. Moreover T. thermophilus and S. coelicolor which do not possess an OAT able to acetylate glutamate with acetylCoA, most probably depend on their arg(A) homologue for arginine biosynthesis.

The gene-enzyme relationship for the first committed step of arginine biosynthesis must now be considered in a new perspective. Several alternatives can be recognized:

i. The classical NAGS originally found in E. coli and Pseudomonas has two domains: an N-terminal one, with a carbamate kinase fold, displays extensive similarity with acetylglutamate kinase (NAGK), while the C-terminal one contains an N-acetyltransferase fold. This classical NAGS may occur in organisms with an acetylornithinase (ArgE) or an ornithine acetyltransferase (ArgJ), two situations epitomized by E. coli and P. aeruginosa. In P. aeruginosa, where ArgJ only recycles the acetylgroup from acetylornithine, NAGS fulfils an anaplerotic, but essential function, priming arginine biosynthesis with the acetyl group from acetyl-CoA [1,2].

ii. In B. stearothermophilus and T. neapolitana the ArgJ (OAT) protein is bifunctional: not only does it recycle the acetyl group, but it also catalyzes the first step (EC 2.3.1.1). Early data concerning expression of B. subtilis genes in E. coli [24], reinterpreted after sequencing of the cognate DNA show that this bacterium also has a bifunctional OAT. In principle, such organisms do not need a NAGS, an assumption corroborated by the actual lack of a NAGS gene in the genomes of their close relatives, B. subtilis and T. maritima. It is worth noting that bifunctional OAT does not show recognizable similarity with NAGS despite the fact that they catalyze the same reaction [5,19].

iii. In eukaryotes, reaction EC 2.3.1.1 is carried out by different kinds of multidomain proteins that are not homologous. In fungi, NAGS activity actually requires association of NAGS with NAGK [25,26] but contrary to what occurs in prokaryotes, there is no significant similarity between NAGS and NAGK (the carbamate kinase fold). On the other hand, mammalian NAGS is similar to the bimodular E. coli NAGS: it possesses a carbamate kinase fold and is able to complement an argA mutant of E. coli [27].

iv. The discovery of the in vivo active Moritella arg(A) sequence fused to the argH gene, and the detection of several homologous argH(A) sequences among marine Proteobacteria including species devoid of NAGS (I. loihiensis, P. haloplanktis) indicates that reaction EC 2.3.1.1 can be catalyzed by a short version of NAGS corresponding to the C-terminal domain of the bimodular NAGS. Furthermore, a number of previously uncharacterized acetyltransferases from different prokaryotes are homologous to this shorter version and the recent biochemical characterization of one of them in M. tuberculosis strongly suggests that many organisms rely on this monodomain form of NAGS to synthesize acetylglutamate.

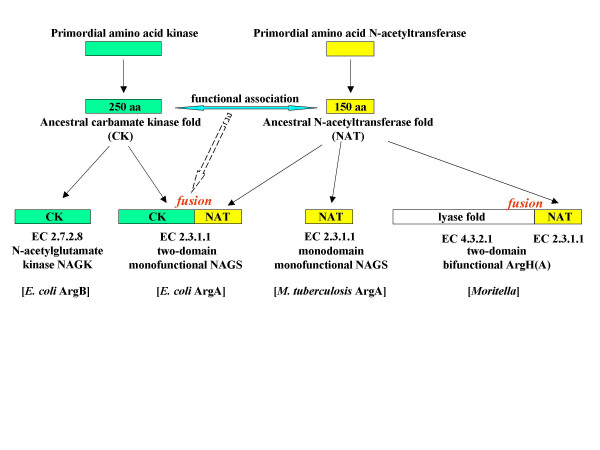

Perhaps this monodomain Arg(A)-like sequence is a primordial enzyme originally recruited from an ancient pool of N-acetyltransferases (see Fig. 7 for a possible evolutionary scheme). The classical, two-domain NAGS may have arisen under selection for an efficient glutamate-binding site as the result of a fusion between this protein and an N-terminal domain which is also found in NAGK. It must be noted that the monodomain M. tuberculosis NAGS has a considerably higher Km for glutamate than the E. coli two-domain one [10]. Association with NAGK, perhaps by providing an efficient glutamate-binding site, may alleviate this kinetic shortcoming. This association may have preceded the advent of the classical NAGS by fusion of the two domains into a single protein (see Fig. 7). In organisms with an argH(A) fusion, physical association between ArgH and Arg(A) might enhance Arg(A) activity or stability and perhaps render the enzyme sensitive to arginine as a feedback inhibitor, since arginine is a product of the reaction catalyzed by ArgH. At any rate, a capital effect of the fusion is probably to have brought arg(A) under regulated expression by arginine. The presence of a classical NAGS (gene argA) along with the argH(A) sequence in some organisms (vibrio-like, enterics) having an AO (ArgE) but no OAT (ArgJ) could be explained by the fact that such organisms are unable to recycle the acetyl group and therefore require a larger flow of acetylglutamate. This hypothesis can be tested by comparing such organisms with Idiomarina and Pseudoalteromonas (where argA-encoded NAGS is absent) for growth and glutamate acetylation kinetics.

Figure 7.

Evolution of glutamate acetylation from a primordial N- acetyltransferase. The recruitment of a primordial N-acetyltransferase for L-glutamate acetylation in the first step of arginine biosynthesis has been made according to at least three different evolutionary ways. The events of gene duplication and gene fusion that allowed evolution toward either the two-domain N-acetylglutamate synthase (EC 2.3.1.1) or the bifunctional argH(A) fusion are schematized. This scheme does not specify whether the argH(A) fusion arose in an organism originally devoid of NAGS or in an organism having lost NAGS. The yellow domains in contemporary proteins (bottom line) are bearing the ArgA activity (EC 2.3.1.1). The contemporary proteins that have been experimentally studied are indicated between brackets.

Due to a lack of biochemical evidence for OAT, we do not know which of the two isoforms, mono or bifunctional, is the more widespread and possibly the primordial one. One possibility is that an arginine pathway using a bifunctional OAT and devoid of NAGS is the most ancestral version of the biosynthesis and that the various forms of NAGS we have been discussing appeared under selection after a mutation transformed a bifunctional OAT into a monofunctional enzyme. The acetylornithinase found in enteric and vibrio- like bacteria may have emerged after loss of such an OAT (7).

The alternatives emphasized in the present survey do not appear to exhaust the variety of solutions implemented in nature for the N-acetylation of glutamate. Archaea such as M. jannaschii have a monofunctional OAT [5] but no homologues of either mono- or two-domain ArgA could be revealed by our investigations. It is therefore possible that in such organisms the reaction EC 2.3.1.1 is carried out by yet another protein. In this respect, organisms such as Xanthomonas appear rather puzzling. In the entirely sequenced genomes of the three available species, a gene encoding a short protein similar to an acetyltransferase has been annotated argA. However, although this gene is clearly inside the arg cluster (between argC and argB) it does not appear as homologous to any of the known mono- or two-domain ArgA proteins and it is absent from the closely related Xylella species. It might therefore represent a new acetylglutamate synthetase or been incorrectly annotated.

In conclusion, our concept of the gene-enzyme relationships in arginine biosynthesis is undergoing a drastic revision among prokaryotes. Far from being universal, the patterns of acetylation of the intermediates may differ in phyla and even within the same phylum. The basic acetylation strategy that segregates arginine and proline precursors in different pathways is not brought into question, but the identity and the origin of the enzymes responsible for glutamate acetylation appears to betray extensive "natural tinkering" [28]. Further phylogenetic analysis and the structural characterization of the cognate proteins will hopefully shed some light on the evolution of this crucial metabolic step.

Methods

Identifying all sequences homologous to the Arg(A) domain

In a first step, the M. abyssi sequence [7] was used as a query to collect the ArgH(A) homologous sequences from the last version (September 2005) of Uniprot (SwissProt and TREMBL) using the Blast facilities of the ExPaSy server [29] and the following criteria : ranking among the best E-values and aligning along the full length (around 620 aa) of the query. Note that several of the found homologues have been incorrectly annotated as "bifunctional protein ArgH" (V. parahaemolyticus), "argininosuccinate lyase" (I. loihiensis, V. vulnificus YJ016), "amino-acid acetyltransferase" (V. fischeri), N-acetylglutamate synthase (V. vulnificus CMCP6). These ArgH(A) sequences were immediately followed in the Blast outfile by the whole set of ArgH proteins (around 450 residues long). Preliminary sequence data was obtained from [30] in the case of Aeromonas hydrophila.

In a second step, the sequence of the domain (A) of the ArgH(A) protein of M. abyssi (KAVGTFAVTEKHNQVTGCASIYVYDTGLAELRSLGIEPGYQGGGQGKAVVEYMLRKAEQMAIQKVFVLTRVPEFFMKLGFRSTSKSMLPEKVLKDCDMCPRQHACDEVALEFKLNVVGQTINLKAEKLAS) was further used do detect (A) homologues. We first identified a list of short (150–180 residues) proteins generally annotated as putative acetyltransferases and, in a second, more distant wave, the acetyltransferase domain of the canonical ArgA (NAGS) such as that of E. coli.

Reconstructing phylogenetic trees

All the (A) homologous sequences were multiply aligned using ClustalX [31]. The arg(A)-like sequences were virtually fused in silico with argH sequences from the same organism in order to build so-called argHX sequences. The ArgH(A) and ArgHX sequences were further mutiply aligned. Both automatic alignments were manually improved using the BioEdit software [32], saved in PHYLIP format and further used to reconstruct phylogenetic trees applying a two-step maximum likelihood approach as follows. After computing a BIONJ [33] distance tree using the Dayhoff model of evolution [34], program Phyml [35] was employed to refine this initial distance tree and to optimize its topology using a discrete-gamma model to accommodate rate variation among sites. The shape parameter alpha of the gamma distribution was estimated as described in [36] and found to be 3.74, the proportion of invariant sites being 0.065. The confidence limits for each node were further estimated using the non-parametric bootstrap approach of the Phyml program with 100 computed data sets.

Authors' contributions

YX and NG were at the origin of this work that extends their initial discovery. NG and BL designed the approach to hunt for relevant homologous sequences and YX and BL made the phylogenetic studies. NG and BL wrote the manuscript that has been read and approved by the three authors.

Figure 2.

Reactions involving L-glutamate. This figure has been drawn using the tools available at Metacyc [37].

Table 1.

Full names of in alphabetical order species used in phylogenetic studies

| Abbreviation | Complete species name a |

| AGRTU | Agrobacterium tumefaciens |

| AQUAE | Aquifex aeolicus |

| ARTSP | Arthrobacter species |

| BACCE | Bacillus cereus |

| BACHA | Bacillus halodurans |

| BACTH | Bacillus thuringiensis |

| CHLLI | Chlorobium limicola |

| CHLTE | Chlorobium tepidum |

| DEHET | Dehalococcoides ethenogenes |

| DEIGE | Deinococcus geothermalis |

| DEIRA | Deinococcus radiodurans |

| DESHA | Desulfitobacterium hafniense |

| DESPS | Desulfotalea psychrophila |

| DESVH | Desulfovibrio vulgaris |

| DESAC | Desulfuromonas acetoxidans |

| GEOKA | Geobacillus kaustophilus |

| GEOME | Geobacter metallireducens |

| GEOSL | Geobacter sulfurreducens |

| HALMA | Haloarcula marismortui |

| HELHE | Helicobacter hepaticus |

| KINRA | Kineococcus radiotolerans |

| LEIXY | Leifsonia xyli |

| LEPIN | Leptospira interrogans |

| METBU | Methanococcoides burtonii |

| METAC | Methanosarcina acetivorans |

| METBA | Methanosarcina barkeri |

| METMA | Methanosarcina mazei |

| MYCLE | Mycobacterium leprae |

| MYCPA | Mycobacterium paratuberculosis |

| MYCTU | Mycobacterium tuberculosis |

| NOCFA | Nocardia farcinica |

| ALCEU | Alcaligenes eutrophus |

| RHIME | Sinorhizobium meliloti |

| PIRBA | Pirellula baltica |

| SOLUS | Solibacter usitatus |

| STRAV | Streptomyces avermitilis |

| STRCO | Streptomyces coelicolor |

| SYMTH | Symbiobacterium thermophilum |

| THEFU | Thermobifida fusca |

| THETH | Thermus thermophilus |

| VIBPA | Vibrio parahaemolyticus |

| WOLSU | Wolinella succinogenes |

a Names of species used in the alignment of ArgHX sequences are listed as found in the phylogenetic tree shown on Figs. 3 and 4.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We are very much indebted to Claudine Médigue and Antoine Danchin for kindly sending us before publication crucial information obtained from their annotation of the genome of Pseudoalteromonas haloplanktis that has been sequenced by Genoscope [23]. We also thank our colleague Troy Philipps, at the University of Southern California, for critically reading the manuscript.

Aeromonas hydrophila preliminary sequence data was obtained from The Institute for Genomic Research [30].

BL wishes to thank the CNRS for support through the UMR 8621.

Contributor Information

Ying Xu, Email: xuyingbelgium@yahoo.com.

Nicolas Glansdorff, Email: nglansdo@vub.ac.be.

Bernard Labedan, Email: bernard.labedan@igmors.u-psud.fr.

References

- Caldovic L, Tuchman M. N-acetylglutamate and its changing role through evolution. Biochem J. 2003;372:279–290. doi: 10.1042/BJ20030002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlier D, Glansdorff N. Biosynthesis of arginine and polyamines. In: Curtiss R III (Editor in Chief), editor. EcoSal – Escherichia coli and Salmonella: Cellular and Molecular Biology Online. ASM Press, Washington, D. C.; Module 3.6.1.10; 2004. http://www.ecosal.org [Google Scholar]

- Shi D, Gallegos R, DePonte J, 3rd, Morizono H, Yu X, Allewell NM, Malamy M, Tuchman M. Crystal structure of a transcarbamylase-like protein from the anaerobic bacterium Bacteroides fragilis at 2.0 A resolution. J Mol Biol. 2002;320:899–908. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(02)00539-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi D, Morizono H, Xiaolin Y, Roth L, Caldovic L, Allewell NM, Malamy MH, Tuchman M. Crystal structure of N-acetylornithine transcarbamylase from Xanthomonas campestris: a novel enzyme in a new arginine biosynthetic pathway found in several eubacteria. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:14366–14369. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C500005200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marc F, Weigel P, Legrain C, Almeras Y, Santrot M, Glansdorff N, Sakanyan V. Characterization and kinetic mechanism of mono- and bifunctional ornithine acetyltransferases from thermophilic microorganisms. Eur J Biochem. 2000;267:5217–5226. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01593.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Murga ML, Gil-Ortiz F, Llacer J, Rubio V. Arginine biosynthesis in Thermotoga maritima: characterization of the arginine-sensitive N-acetyl-L-glutamate kinase. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:6142–6149. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.18.6142-6149.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y, Liang Z, Legrain C, Ruger HJ, Glansdorff N. Evolution of arginine biosynthesis in the bacterial domain: novel gene-enzyme relationship from psychophilic Moritella strains (Vibrionaceae) and the evolutionary significance of N-α- acetylornithinase. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:1609–1615. doi: 10.1128/JB.182.6.1609-1615.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y, Nogi Y, Kato C, Ruger HJ, De Kegel D, Glansdorff N. Moritella profunda sp. nov. and Moritella abyssi sp. nov., new psychropiezophilic species from deep Atlantic sediments. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2003;53:533–8. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.02228-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramon-Maiques S, Marina A, Gil-Ortiz F, Fita I, Rubio V. Structure of acetylglutamate kinase, a key enzyme for arginine biosynthesis and a prototype for the amino acid kinase enzyme family, during catalysis. Structure. 2002;10:329–342. doi: 10.1016/S0969-2126(02)00721-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Errey JC, Blanchard JS. Functional characterization of a novel ArgA from Mycobacterium tuberculosis . J Bacteriol. 2005;187:3039–3044. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.9.3039-3044.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanova EP, Flavier S, Christen R. Phylogenetic relationships among marine Alteromonas -like proteobacteria'; emended description of the family Alteromonadaceae and proposal of Pseudoalteromonadaceae fam. nov., Colwelliaceae fam. nov., Shewanellaceae fam. nov., Moritellaceae fam. nov., Ferrimonadaceae fam. nov., Idiomarinaceae fam. nov. and Psychromonadaceae fam. nov. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2004;54:1773–1788. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.02997-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou S, Saw JH, Lee KS, Freitas TA, Belisle C, Kawarabayasi Y, Donachie SP, Pikina A, Galperin MY, Koonin EV, Makarova KS, Omelchenko MV, Sorokin A, Wolf YI, Li QX, Keum YS, Campbell S, Denery J, Aizawa S, Shibata S, Malahoff A, Alam M. Genome sequence of the deep-sea gamma-proteobacterium Idiomarina loihiensis reveals amino acid fermentation as a source of carbon and energy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:18036–41. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407638102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tosco A, Birolo L, Madonna S, Lolli G, Sannia G, Marino G. GroEL from the psychrophilic bacterium Pseudoalteromonas haloplanktis TAC 125: molecular characterization and gene cloning. Extremophiles. 2003;7:17–28. doi: 10.1007/s00792-002-0291-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez R, Roovers M, Glansdorff N. Organization and expression of a Thermus thermophilus arginine cluster: presence of unidentified open reading frames and absence of a Shine-Dalgarno sequence. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:5911–5. doi: 10.1128/JB.182.20.5911-5915.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sassetti CM, Boyd DH, Rubin EJ. Genes required for mycobacterial growth defined by high density mutagenesis. Mol Microbiol. 2003;48:77–84. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03425.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakanyan V, Petrosyan P, Lecocq M, Boyen A, Legrain C, Demarez M, Hallet JN, Glansdorff N. Genes and enzymes of the acetyl cycle of arginine biosynthesis in Corynebacterium glutamicum: enzyme evolution in the early steps of the arginine pathway. Microbiology UK. 1996;142:99–108. doi: 10.1099/13500872-142-1-99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baetens M, Legrain C, Boyen A, Glansdorff N. Genes and enzymes of the acetyl cycle of arginine biosynthesis in the extreme thermophilic bacterium Thermus thermophilus. Microbiology UK. 1998;144:479–492. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-2-479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hindle Z, Callis R, Dowden S, Rudd BA, Baumberg S. Cloning and expression in Escherichia coli of a Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) argCJB cluster. Microbiology UK. 1994;140:311–320. doi: 10.1099/13500872-140-2-311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weigel P, Marc F, Simon S, Sakanyan V. Ornithine N-acetyltransferase and arginine biosynthesis in thermophilic bacteria. Recent Res Devel Microbiol. 2002;6:95–106. [Google Scholar]

- Neuwald AF, Landsman D. GCN5-related histone N -acetyltransferases belong to a diverse superfamily that includes the yeast SPT10 protein. Trends Biochem Sci. 1997;22:154–155. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(97)01034-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vetting MW, de Carvalho LPS, Yu M, Hegde SS, Magnet S, Roderick SL, Blanchard JS. Structure and functions of the GNAT superfamily of acetyltransferases. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2005;433:212–226. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2004.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachmann C, Krahenbuhl S, Colombo JP. Purification and properties of acetyl-CoA: L-glutamate N-acetyltransferase from human liver. Biochem J. 1982;205:123–127. doi: 10.1042/bj2050123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Médigue C, Krin E, Pascal G, Barbe V, Bernsel A, Bertin PN, Cheung F, Cruveiller S, D'Amico S, Duilio A, Fang G, Feller G, Ho C, Mangenot S, Marino G, Nilsson J, Parrilli E, Rocha EPC, Rouy Z, Sekowska A, Tutino ML, Vallenet D, von Heijne G, Danchin A. Coping with cold: The genome of the versatile marine Antarctica bacterium Pseudoalteromonas haloplanktis TAC125. Genome Res. 2005;15:1325–1335. doi: 10.1101/gr.4126905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mountain A, Mc Chesney J, Smith MCM, Baumberg S. Gene sequence encoding early enzymes of arginine synthesis within a cluster in Bacillus subtilis, as revealed by cloning in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1986;165:1026–1028. doi: 10.1128/jb.165.3.1026-1028.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JH, Weiss RL. Genetic analysis of interactions between arg-14 and arg-6 products in Neurospora crassa. Mol Cells. 1995;5:461–466. [Google Scholar]

- Pauwels K, Abadjieva A, Hilven P, Stankiewicz A, Crabeel M. The N-acetylglutamate synthase/N-acetylglutamate kinase metabolon of Saccharomyces cerevisiae allows co-ordinated feedback regulation of the first two steps in arginine biosynthesis. Eur J Biochem. 2003;270:1014–24. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2003.03477.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morizono H, Caldovic L, Shi D, Tuchman M. Mammalian N- acetylglutamate synthase. Mol Gen Metab. 2004;81:S4–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2003.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob F. Evolution and tinkering. Science. 1977;196:1161–1166. doi: 10.1126/science.860134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ExPaSy server, Blast facilities http://www.expasy.org/tools/blast/

- The Institute for Genomic Research http://www.tigr.org

- Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Plewniak F, Jeanmougin F, Higgins DG. The ClustalX windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Research. 1997;25:4876–4882. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.24.4876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BioEdit http://www.mbio.ncsu.edu/BioEdit/bioedit.html

- Guindon S, Gascuel O. Efficient biased estimation of evolutionary distances when substitution rates vary across sites. Mol Biol Evol. 2002;19:534–43. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a004109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dayhoff MO, Schwartz RM, Orcutt BC. A model of evolutionary change in proteins. In: Dayhoff MO (ed.), editor. Atlas of Protein Sequence Structur. Vol. 5. National Biomedical Research Foundation, Washington DC; 1978. pp. 3345–352. [Google Scholar]

- Guindon S, Gascuel O. A simple, fast, and accurate algorithm to estimate large phylogenies by maximum likelihood. Syst Biol. 2003;52:696–704. doi: 10.1080/10635150390235520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z. Maximum likelihood phylogenetic estimation from DNA sequences with variable rates over sites: approximate methods. J Mol Evol. 1994;39:306–14. doi: 10.1007/BF00160154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karp PD, Paley S, Romero P. The Pathway Tools Software. Bioinformatics. 2002;18:S225–32. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/18.suppl_1.s225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]