Abstract

The endocytic pathway of eukaryotes is essential for the internalization and trafficking of macromolecules, fluid, membranes, and membrane proteins. One of the most enigmatic aspects of this process is endocytic recycling, the return of macromolecules (often receptors) and fluid from endosomes to the plasma membrane. We have previously shown that the EH-domain protein RME-1 is a critical regulator of endocytic recycling in worms and mammals. Here we identify the RAB-10 protein as a key regulator of endocytic recycling upstream of RME-1 in polarized epithelial cells of the Caenorhabditis elegans intestine. rab-10 null mutant intestinal cells accumulate abnormally abundant RAB-5-positive early endosomes, some of which are enlarged by more than 10-fold. Conversely most RME-1-positive recycling endosomes are lost in rab-10 mutants. The abnormal early endosomes in rab-10 mutants accumulate basolaterally recycling transmembrane cargo molecules and basolaterally recycling fluid, consistent with a block in basolateral transport. These results indicate a role for RAB-10 in basolateral recycling upstream of RME-1. We found that a functional GFP-RAB-10 reporter protein is localized to endosomes and Golgi in wild-type intestinal cells consistent with a direct role for RAB-10 in this transport pathway.

INTRODUCTION

Endocytosis and endocytic trafficking controls the uptake and sorting of extracellular macromolecules as well as the components of the cell membrane itself, counterbalancing secretion and allowing a complex interplay between cells and their environment that is important for a myriad of cellular activities (Brodsky et al., 2001; Maxfield and McGraw, 2004). The steps involved in the uptake and trafficking of cargo within the endosomal system have been well described, but many of the components mediating these steps at the molecular level remain to be identified (Brodsky et al., 2001; Maxfield and McGraw, 2004). Many receptors and their associated ligands cluster into clathrin-coated pits, whereas other types of cargo utilize clathrin-independent uptake mechanisms (Nichols, 2003; Gesbert et al., 2004). Plasma membrane invaginations pinch off into vesicles, uncoat, and then fuse with one another and with early endosomes. In early endosomes some ligand-receptor complexes dissociate because of the reduced pH of the endosomal lumen (Mukherjee et al., 1997). Many receptors then recycle to the plasma membrane (PM) either directly or indirectly via recycling endosomes (Mukherjee et al., 1997; Maxfield and McGraw, 2004). Many ligands do not recycle but instead are transported from early to late endosomes and eventually to lysosomes for degradation (Mukherjee et al., 1997). In polarized epithelial cells such as cultured Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells, an additional layer of complexity in the endocytic pathway contributes to formation and/or maintenance of the specialized apical and basolateral domains (Nelson and Yeaman, 2001; Mostov et al., 2003; Hoekstra et al., 2004). Both the apical and basolateral membranes deliver cargo to early endosomes. Basolaterally derived and apical cargo can reach medially located “common endosomes,” which can sort cargo from either source to the basolateral PM or to apical recycling endosomes (ARE), which can then ultimately send cargo to the apical PM (Brown et al., 2000; Wang et al., 2000; Hoekstra et al., 2004).

One group of master regulators of trafficking that has come under intense scrutiny are the Rab proteins, members of the Ras superfamily of small GTPases (Zerial and McBride, 2001). The human genome encodes >60 Rab proteins, whereas the Caenorhabditis elegans genome encodes 29 predicted members (Pereira-Leal and Seabra, 2001). Each step in membrane transport is thought to require at least one such Rab protein (Pfeffer, 1994; Zerial and McBride, 2001). Rabs act to recruit effector proteins to membranes and have been proposed to regulate transport in several ways including promoting vesicle formation and recruitment of cargo into budding transport carriers, promoting molecular motor-based movement of vesicles toward target membranes, and regulating fusion of vesicles with target membranes (Zerial and McBride, 2001). Similar to Ras, Rab GTPases cycle between an active GTP-bound state and an inactive GDP-bound state. GDP-bound Rab proteins are primarily found in the cytoplasm bound to GDP dissociation inhibitor (GDI; Seabra and Wasmeier, 2004). GDI protein delivers GDP-bound Rab proteins to donor membranes where GDI is replaced by a GDI displacement factor (GDF; Pfeffer and Aivazian, 2004). Next, a guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) stimulates replacement of GDP with GTP. Thus, activated Rab-GTP can recruit effectors and promote transport. After membrane docking and fusion, a GTPase-activating protein (GAP) can stimulate the GTPase activity of the Rab protein, leading to GTP hydrolysis and dissociation of the Rab from its effectors. Finally, GDI extracts Rab-GDP from the membrane and recycles it to the donor compartment for another round of transport (Seabra and Wasmeier, 2004).

A number of Rab proteins have been implicated in the endocytic recycling pathway including Rab4, Rab11, and Rab15 in the clathrin pathway, and Rab22 and the more distantly related Arf6 in the recycling of cargo internalized independently of clathrin (van der Sluijs et al., 1992; Ullrich et al., 1996; Sheff et al., 1999; Zuk and Elferink, 2000; Kauppi et al., 2002; Naslavsky et al., 2004; Weigert et al., 2004). In nonpolarized cells Rab4 is primarily associated with early endosomes and is thought to contribute to direct transport from early endosomes to the plasma membrane as well as early endosome to recycling endosome transport (Sheff et al., 1999). In MDCK cells Rab4 has also been reported to associate with early endosomes and a later compartment named the common endosome, where is promotes apical delivery of transcytotic cargo (Mohrmann et al., 2002). Rab11 is primarily associated with recycling endosomes and has been reported to act after Rab4 in nonpolarized cells, mediating recycling endosome to PM transport of clathrin-dependent and clathrin-independent recycling cargo (Sheff et al., 1999; Weigert et al., 2004). In polarized cells Rab11 is primarily associated with the ARE and is thought to function in the transport of cargo from the ARE to the PM (Casanova et al., 1999; Sheff et al., 1999; Brown et al., 2000). Arf6 and Rab22 are thought to specifically regulate the recycling of cargo that does not depend on clathrin for its internalization and act sequentially in such transport (Weigert et al., 2004). In polarized cells Arf6 has been proposed to mediate apical uptake of clathrin-dependent cargo and was not found to mediate recycling (Altschuler et al., 1999).

Recently, we and others have established in vivo endocytic assay systems for genetic analysis of trafficking in several C. elegans tissues such as oocytes (Grant and Hirsh, 1999), coelomocytes (Fares and Greenwald, 2001a), and the intestine (Grant et al., 2001). Through such genetic analysis in C. elegans, we have identified several new key endocytic regulators such as rme-1 (Grant et al., 2001), rme-6 (Sato et al., 2005), and rme-8 (Zhang et al., 2001) that are conserved from worm to human but lack clear homologues in yeast, the traditional genetic system for analysis of trafficking.

In our current studies we have focused on the endocytic recycling pathways of polarized epithelial cells. In particular we have focused on the C. elegans intestine, a polarized epithelial tube one cell layer thick (Leung et al., 1999). The apical microvillar surface faces the lumen and is responsible for nutrient uptake from the environment (see Supplementary Figure S1). The basolateral surface faces the pseudocoelom (body cavity) and is responsible for the exchange of molecules between the intestine and the rest of the body (see Supplementary Figure S1). Several endocytic tracers such as the lipophilic dye FM4-64 and fluid-phase markers such as rhodamine-dextran, Texas Red-BSA, or GFP secreted by muscle cells have been used in the studies of C. elegans intestinal endocytosis (Grant et al., 2001). When such tracers are taken up by the intestine lumen (apical surface), they all accumulate in the gut granules (lipofuscin-positive lysosomes; Grant et al., 2001). On the contrary, when these tracers are applied to the pseudocoelom by microinjection (or by expression in the case of GFP) and taken up from the basolateral plasma membrane of the intestine, only the FM 4–64 dye reaches the lysosomes while the fluid-phase markers are instead recycled back to the pseudocoelom (Grant et al., 2001).

rme-1 mutants display endocytic recycling defects in several tissues (Grant et al., 2001). These defects include strongly reduced uptake of yolk proteins by oocytes, because of poor recycling of yolk receptors, reduced uptake of fluid-phase markers by coelomocytes, and the accumulation of gigantic fluid-filled recycling endosomes in the intestinal cells, due to defective recycling of pseudocoelomic fluid (Grant et al., 2001). The accumulation of large fluid-filled endosomes in the worm intestine is a hallmark phenotype that can be used to identify mutants with basolateral recycling defects. Although it is sometimes difficult to image fluid phase markers in recycling endosomes in normal cells, perhaps because cargo is diluted within thin membrane tubules, the recycling of endocytosed fluid has been amply demonstrated in cultured mammalian cells (Tooze and Hollinshead, 1991; Apodaca et al., 1994b; Barroso and Sztul, 1994). At least 50% of internalized fluid recycles back into the culture medium, presumably in the same transport carriers as recycling receptors (Besterman et al., 1981; Bomsel et al., 1989; Gagescu et al., 2000). When recycling is blocked by pharmacological means in either MDCK cells (Apodaca et al., 1994a) or HepG2 cells (van Weert et al., 2000) gigantic endosomal structures similar to those described in C. elegans rme-1 mutant intestinal cells are formed.

Here we report molecular cloning and functional characterization of gum-1 (gut morphology abnormal-1), a mutant that displays a rme-1-like mutant phenotype in the worm intestine. We show that gum-1 is required for basolateral endocytic recycling in the C. elegans intestine and that gum-1 is the C. elegans rab-10 gene. We provide evidence that C. elegans RAB-10 is physically associated with early endosomes and Golgi and propose that RAB-10 functions upstream of RME-1 in the basolateral transport of fluid and other recycling cargo.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

General Methods and Strains

All C. elegans strains were derived originally from the wild-type Bristol strain N2. Worm cultures, genetic crosses, and other C. elegans husbandry were performed according to standard protocols (Brenner, 1974). A complete list of strains used in this study can be found in Supplementary Figure S2. Three assays were performed to monitor steady-state endocytosis in oocytes, coelomocytes, and the intestine of worms. Oocyte endocytosis was assayed by using a transgenic strain bIs1[vit-2::GFP] expressing a YP170-GFP fusion protein (Grant and Hirsh, 1999). Transgenic strain arIs37[myo-3::ssGFP, dpy-20(+)] expressing a secreted form of GFP expressed by muscle cells and released into the body cavity was used for coelomocyte assays (Fares and Greenwald, 2001a). Basolateral endocytosis by the intestine was also be visualized using muscle-secreted GFP as a fluid-phase marker. In some cases a cup-4 mutation was also included in the assay to reduce uptake by coelomocytes and increase availability of the marker in the body cavity (Patton et al., 2005).

RNAi was performed by the feeding method (Timmons and Fire, 1998). Feeding constructs were prepared by PCR from EST clones provided by Dr. Yuji Kohara (National Institute of Genetic, Japan) followed by subcloning into the RNAi vector L4440 (Timmons and Fire, 1998). L4-stage worms were used for RNAi assay and phenotypes were scored in the same animals as adults.

Mutant Isolation, Genetic Mapping, and Molecular Cloning

The q373 allele was originally isolated as a spontaneous mutant arising from a Bristol N2 stock. gum-1(q373) was mapped to the interval between bli-4 and unc-13 on chromosome I by standard three-factor mapping. The dx2 allele was isolated in a noncomplementation screen performed by crossing EMS-treated N2 males with gum-1(q373) unc-13(e51) hermaphrodites screening F1 progeny for the Gum-nonUnc phenotype.

To identify gum-1-containing DNA fragments, cosmids (10–20 μg/ml) containing C. elegans genomic DNA together with the dominant transgenic marker rol-6(su1006) (plasmid pRF4, 100 μg/ml) were microinjected into gum-1(q373) worms to establish transgenic strains and assayed for rescue of the intestinal phenotype. Only the cosmid clone T23H2 displayed rescuing activity. The rescuing activity was further narrowed to the T23H2.5 gene by microinjection of PCR products of individual predicted genes within T23H2. Subsequently we found that RNAi of T23H2.5 was able to phenocopy the gum-1 intestinal phenotype in wild-type animals. To identify mutations in gum-1 mutants, the complete T23H2.5 genomic region was amplified by PCR and sequenced directly using nested primers. To confirm the coding region of gum-1/rab-10, the apparently full-length cDNA clone yk586g1 was sequenced.

Plasmids and Transgenic Strains

To construct the GFP-RAB-10 transgene driven by its own promoter, 2.9 kb of RAB-10 promoter sequence was PCR amplified from C. elegans genomic DNA with primers ggatcctctcttgtctgtatctctggtc (Bam-t23h2.5promF) and ggtaccaagtcatacggtcggcgagccatt (Asp-t23h2.5promR) containing BamHI and Asp718I restriction sites and cloned into the same sites in the C. elegans GFP vector pPD117.01 (gift of Andrew Fire) to generate the plasmid 2.9GFP. The entire genomic exon/intron and 3′ UTR was then PCR amplified with primers gaattcatggctcgccgaccgtatgac (RI-t23h2.5genebodyF) and gccggcattgcgttgaacggtgtcatc (Ngo-t23h2.5genebodyR) including EcoRI and NgoMIV restriction sites and cloned into the same sites downstream of GFP in the 2.9GFP vector to generate the GFP-rab-10 plasmid. The 2.9GFP or GFP-rab-10 plasmids (8 μg) were cobombarded with plasmid MM016B, encoding the wild-type unc-119 gene (8 μg), into unc-119(ed3) mutant worms to establish transgenic lines by the microparticle bombardment method (Praitis et al., 2001). Integrated transgenic lines pwIs214 and pwIs215 for GFP-rab-10 were generated and produced similar expression patterns. The pwIs214 line was crossed into a rab-10(dx2) background and was found to rescue the intestinal vacuole phenotype. Most analysis presented here used the pwIs214 line. Five integrated lines (pwIs262–266) were isolated for the 2.9GFP promoter construct.

To construct GFP or RFP fusion transgenes for expression in the worm intestine, two Gateway destination vectors were prepared using the promoter region of the intestine-specific gene vha-6 cloned into the C. elegans pPD117.01 vector, followed by GFP or RFP coding sequences, a Gateway cassette (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and let-858 3′ UTR sequences, followed by the unc-119 gene of C. briggsae. The genomic or cDNA sequences of C. elegans rab-5, rab-7, rab-10, rab-11, rme-1, or human Rab10 genes were cloned individually into entry vector pDONR221 and then transferred into vha-6-GFP (or RFP)-vectors by Gateway recombination cloning to generate N-terminal fusions. The human TfR (transferrin receptor), human TAC (alpha-chain of the IL-2 receptor), and a fragment of C. elegans alpha-mannosidase II (F58H1.1, first 82 aa including signal sequence/TM-anchor domain as in Rolls et al., 2002) were cloned into a similar vector upstream of GFP to generate C-terminal fusions. Complete plasmid sequences are available on request. Low copy integrated transgenic lines were obtained by the microparticle bombardment method (Praitis et al., 2001).

Microscopy and Image Analysis of Worm Intestines

Live worms were mounted on 2% agarose pads with 10 mM levamisol as described previously (Sato et al., 2005). Fluorescence images were obtained using an Axiovert 200M (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging, Oberkochen, Germany) microscope equipped with a digital CCD camera (C4742–12ER, Hamamatsu Photonics, Hamamatsu, Japan), captured using Metamorph software (Universal Imaging, West Chester, PA), and then deconvolved using AutoDeblur software (AutoQuant Imaging, Watervliet, NY). Images taken in the DAPI channel were used to identify broad-spectrum intestinal autofluorescence caused by lipofuscin-positive lysosomes (Clokey and Jacobson, 1986). To obtain images of GFP fluorescence without interference from autofluorescence, we used a Zeiss LSM510 Meta confocal microscope system (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging). We determined that the GFP fluorescence peak at 510 nm lacked significant contributions from autofluorescent lysosomes. Thus confocal images shown depict only this wavelength peak and depict GFP only. Quantification of images was performed with Metamorph software (Universal Imaging). Most GFP/RFP colocalization analysis was performed on L3 larvae generated as F1 cross-progeny of GFP-RAB-10 males crossed to RFP-marker hermaphrodites.

RESULTS

gum-1 Mutants Display rme-1-like Endocytosis Defects in the Intestine

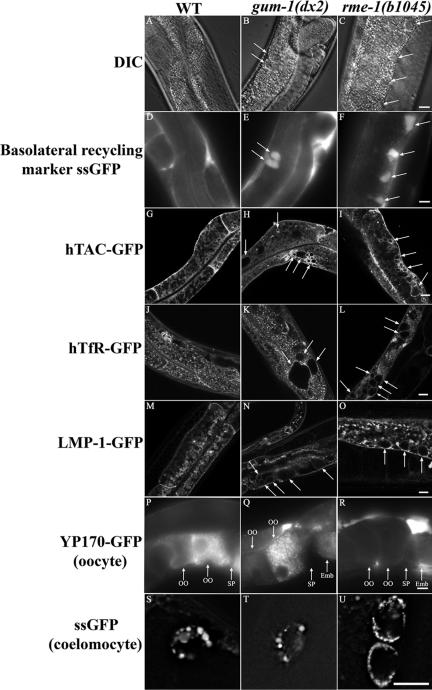

rme-1 mutants display endocytic trafficking defects in several C. elegans tissues. These defects include the accumulation of large vacuoles in the intestinal cells, strongly reduced uptake of yolk proteins by oocytes due to poor yolk receptor recycling, and reduced uptake of fluid-phase markers by coelomocytes (Grant et al., 2001). RME-1 is thought to function specifically in endocytic recycling, and the vacuoles that accumulate in rme-1 mutant intestinal cells are thought to be grossly enlarged basolateral recycling endosomes (Grant et al., 2001). To identify additional proteins that function in endocytic recycling, we screened for new mutants with rme-1-like intestinal phenotypes. One such mutant, gum-1(q373) (Gut morphology abnormal-1) was isolated. We isolated an additional allele of gum-1, dx2, in a genetic complementation screen with q373. In both of these gum-1 mutants, large, transparent vacuoles accumulate in the worm intestine similar to those observed in rme-1 mutant worms (Figure 1, A–C).

Figure 1.

gum-1 mutants display an intestinal phenotype similar to that of rme-1 mutants. (A–C) Nomarski images of the intestine in wild-type, gum-1(dx2), and rme-1(b1045) worms. (A) No large transparent vacuoles were observed in the intestines of wild-type worms. (B) Very large transparent vacuoles are found in the intestines of gum-1(dx2) and (C) rme-1(b1045) mutant worms. Arrows indicate the positions of vacuoles. Intestinal endocytosis of the basolateral recycling marker ssGFP in (D) wild-type, (E) gum-1(dx2), and (F) rme-1(b1045) mutants. In wild-type worms very little secreted GFP accumulates in intestinal endosomes because of efficient recycling back to the body cavity (D). The gum-1- and rme-1-specific vacuoles accumulate basolaterally endocytosed GFP (E and F). A cup-4(ar494) mutation was also included in the strain shown in E to impair coelomocyte function, increasing steady-state levels of secreted GFP in the bodycavity. Similar results are seen in gum-1 single mutants but the endocytosed GFP is less abundant (unpublished data). (G–O) Confocal images of the worm intestine expressing GFP-tagged endocytic transmembrane cargo markers in wild-type, gum-1(dx2), and rme-1(b1045) mutant animals. In wild-type worms, the basolateral PM and basolateral endocytic compartments are labeled by hTAC-GFP (G), hTfR-GFP (human transferrin receptor; J), and LMP-1-GFP (M). In gum-1(dx2) and rme-1(b1045) mutant worms, all three transmembrane cargo markers accumulate in the enlarged endosomes: hTAC-GFP (H and I), hTfR-GFP (K and L), and LMP-1-GFP (N and O), respectively. Arrows indicate the enlarged endosomes. (P–R) Endocytosis of YP170-GFP by the oocytes of adult hermaphrodites. In wild type, YP170-GFP is endocytosed efficiently by oocytes (P). In the rme-1(b1045) mutant, internalization of YP170-GFP by oocytes is dramatically reduced and YP170-GFP accumulates in the body cavity (R). However, in gum-1(dx2) mutant, the secretion of YP170-GFP by the intestine and the endocytosis of YP170-GFP by oocytes is normal (Q). Arrows indicate the YP170-GFP accumulation in the oocytes and embryos. OO, oocyte; SP, spermatheca; Emb, embryo. (S–U) Endocytosis of ssGFP by the coelomocytes of adult hermaphrodites. In the rme-1(b1045) mutant, coelomocyte endocytosis of GFP secreted by muscle cells is reduced and secreted GFP accumulates in the body cavity (unpublished data) and in abnormally small peripheral vesicles of the coelomocytes (U). However, in gum-1(dx2) mutants, the secretion of GFP by muscle and the endocytosis of GFP by coelomocytes is relatively normal (T). Bar, 10 μm.

To determine if the abnormal vacuoles in gum-1 mutant intestines are enlarged basolateral endosomes like those that form in rme-1 mutants, we crossed the gum-1 mutants into the background of a transgene that directs secretion of GFP from body-wall muscle cells into body cavity, from which the secreted GFP is normally endocytosed by the basolateral intestine and then recycled into the body cavity (Fares and Greenwald, 2001a; Grant et al., 2001). We found that the large abnormal vacuoles in gum-1 mutant intestinal cells accumulated GFP from the body cavity, indicating a defect in basolateral recycling similar to that previously found in rme-1 mutants (Figure 1, D–F). Also similar to rme-1 mutants, we found that uptake of the fluid-phase marker Texas-red BSA or the membrane intercalating dye FM 4–64, administered to the apical intestinal membrane by feeding, was normal, and neither marker accumulated in the abnormal vacuoles of gum-1 mutants (unpublished data). Taken together these results indicate that gum-1 mutants, like rme-1 mutants, have severe defects in basolateral endocytic recycling by the intestine.

Next we sought to determine if transmembrane cargo also accumulated in the abnormal endocytic compartments of gum-1 and rme-1 mutants. To test this, we expressed three transmembrane proteins as GFP fusions in the C. elegans intestine and compared their steady-state localization in wild-type animals and with that in gum-1 or rme-1 mutant animals. Equivalent GFP-fusions for these three proteins have previously been shown to be functional and traffic normally in mammalian cells and/or C. elegans. First we expressed the human transferrin receptor (hTfR-GFP), a marker for clathrin-dependent uptake and rme-1-dependent recycling in mammalian cells (Yamashiro et al., 1984; Burack et al., 2000; Lin et al., 2001). Next we expressed the α-chain of the human IL-2 receptor TAC (hTAC-GFP), a marker for clathrin-independent endocytosis and rme-1-dependent recycling in mammalian cells (Caplan et al., 2002; Naslavsky et al., 2004). Finally we examined C. elegans LMP-1 (LMP-1-GFP), a worm homologue of mammalian CD63/LAMP, that is found in lysosomes of coelomocyte cells (Treusch et al., 2004), but that labels other endocytic compartments in the intestine (Hermann et al., 2005).

All three of these markers primarily labeled basolateral membranes in wild-type worm intestine, with apparent localization to the PM and PM proximal small endosomal vesicles and tubules (Figure 1, G, J, and M). In addition to this pattern, LMP-1-GFP also labeled large round vesicular structures near the basolateral membranes (Figure 1M). None of these markers accumulated appreciably on apical membranes or in the autofluorescent lysosomes of the worm intestine. We found that the abnormal vacuoles of gum-1 and rme-1 mutants showed visible accumulation of all three of these transmembrane cargo markers: hTAC-GFP (Figure 1, G–I), hTfR-GFP (Figure 1, J–L), and LMP-1-GFP (Figure 1, M–O). Interestingly, hTAC-GFP labeled the enlarged endosomes more strongly than did hTfR-GFP or LMP-1-GFP. These results suggest that all three of these proteins normally transit through endosomes regulated by GUM-1 and RME-1. The strong accumulation of hTAC-GFP in the enlarged endosomes of gum-1 and rme-1 mutants suggests that hTAC, like fluid internalized from the body cavity, requires GUM-1 and RME-1 for export from these endosomes. The relatively weak labeling of the enlarged endosomes of gum-1 and rme-1 mutants by the other cargo proteins may indicate that they transit these endosomes but are less dependent on GUM-1 or RME-1 for endosome exit.

In one major respect however, gum-1 mutants do not resemble rme-1 mutants. rme-1 mutants display endocytic defects in multiple tissues of C. elegans such as oocytes and coelomocytes. As far as we could determine using standard assays, gum-1 mutants do not show endocytic trafficking defects in oocytes or coelomocytes, suggesting that GUM-1 is required for trafficking in a more restricted set of tissues than RME-1. We assayed oocyte endocytosis of the YP170-GFP yolk protein marker (Grant and Hirsh, 1999), and coelomocyte endocytosis of GFP secreted by muscle cells (Fares and Greenwald, 2001a, 2001b) and found no defects in gum-1 mutants at steady state (Figure 1, P–R and S–U). rme-1 mutants show strong defects in both of these assays (Grant et al., 2001). Similar to rme-1 mutants, basolateral secretion of YP170-GFP by the intestine and secretion of GFP by muscle cells appeared normal in gum-1 mutants, suggesting that gum-1 is not required for secretion. We also note that intestinal vacuoles of gum-1 mutants are generally larger than those of rme-1 mutants, and the changes in intracellular distribution of some transmembrane cargo proteins appears slightly different between the two mutants (Figure 1, K, L, N, and O, and unpublished data).

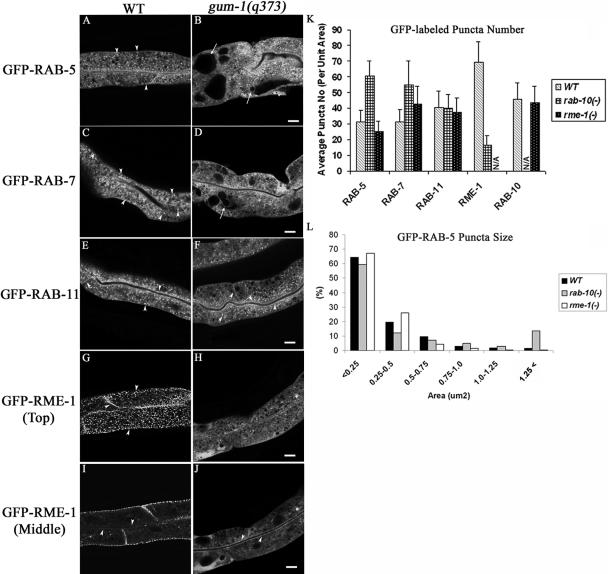

gum-1 Mutations Result in a Dramatic Increase in RAB-5-positive Early Endosome Number with a Concomitant Loss in RME-1-positive Recycling Endosomes

All of these phenotypes suggest that gum-1 mutants are defective in basolateral recycling in the worm intestine. To better understand which step in trafficking is impaired in gum-1 mutants, we crossed a set of intestinally expressed GFP-tagged transgenes, encoding endosomal marker proteins, into gum-1 mutant backgrounds and assayed the effects on endosome morphology. We also performed a parallel analysis in an rme-1 null mutant background for comparison. As we have previously reported (Hermann et al., 2005), wild-type intestinal cells contain abundant, GFP-RAB-5-positive early endosomes that appear as small punctate structures near the basolateral and apical PM and some larger structures in the medial cytoplasm (Figure 2A). With a GFP-RAB-7 marker we see similar small puncta near the PM and abundant larger ringlike structures deeper in the cytoplasm (Figure 2C). These results are consistent with the idea that the small puncta are early endosomes, which are known to label for RAB-5 and RAB-7 in other systems (Zerial and McBride, 2001), whereas the larger ring-like vesicles are late endosomes, known to be RAB-5 negative and RAB-7 positive in other systems. We also examined markers for intestinal recycling endosomes, GFP-RAB-11 (this work) and GFP-RME-1 (Grant et al., 2001; Hermann et al., 2005). In wild-type animals GFP-RAB-11 strongly labels abundant small puncta concentrated near the apical plasma membrane and less frequent puncta scattered in the cytoplasm (Figure 2E), suggesting that RAB-11 marks apical recycling endosomes, as does its ortholog Rab11 in MDCK cells (Casanova et al., 1999). RAB-11 has also been localized to the TGN in some systems and has been implicated in the secretory pathway (Chen et al., 1998). GFP-RME-1 strongly labels tubulo-vesicular endosomes very near the basolateral PM (Figure 2G), thought to be basolateral recycling endosomes. GFP-RME-1 also more weakly labels structures very near the apical PM (Figure 2I) that could be apical recycling endosomes.

Figure 2.

gum-1 mutants accumulate endosomes marked with GFP-RAB-5 and GFP-RAB-7 and lose most endosomes marked with GFP-RME-1. Confocal images in a wild-type background are shown for GFP-RAB-5 (A), GFP-RAB-7 (C), GFP-RAB11 (E), or GFP-RME-1 (G and I). Confocal images in a gum-1(q373) background are shown for GFP-RAB-5 (B), GFP-RAB-7 (D), GFP-RAB11 (F), or GFP-RME-1 (H and J). Similar defects were found in gum-1(dx2) mutants (unpublished data). Arrowheads indicate punctate, tubular, or ringlike endosomes labeled by GFP-RAB-5, GFP-RAB-7, GFP-RAB-11, and GFP-RME-1 in the apical, cytosolic, lateral, or basolateral compartments. Arrows indicate enlarged intestinal endosomes (vacuoles) labeled by GFP-RAB-5 (B) or GFP-RAB-7 (D). Quantification of endosome number as visualized by the markers is shown in K. Error bars represent standard deviations from the mean (n = 24 each, 8 animals of each genotype sampled in three different regions of each intestine). Quantification of GFP-RAB-5-positive endosome size is graphed in L. Bar, 10 μm.

In gum-1 mutants, the GFP-RAB-5- and GFP-RAB-7-positive endosomes accumulated in abnormally high numbers (Figure 2, B, D, and K), but the number of endosomes labeled by GFP-RAB-11 was not affected (Figure 2, F and K). We performed quantitative image analysis on confocal micrographs from these GFP-tagged strains (Figure 2K) and calculated a twofold increase in RAB-5-positive endosome number in gum-1 mutants compared with wild-type animals. We believe that this is an underestimate of the increased number of labeled endosomes, because the endosomes became so abundant in the mutant background that it became difficult to resolve individual puncta. Many, but not all, of the gigantic vacuoles present in gum-1 mutant intestinal cells were positive for GFP-RAB-5 and GFP-RAB-7 (Figure 2, B and D, arrow; and Figure 2L, and Supplementary Figure 3) but not GFP-RAB-11 or GFP-RME-1 (unpublished data), suggesting that many of these structures are grossly enlarged early endosomes. In addition, the tubulovesicular basolateral recycling endosomes normally labeled by GFP-RME-1 were lost almost completely in gum-1 mutants (Figure 2, G–K). GFP-RME-1 appears mostly diffuse in the cytoplasm in gum-1 mutants, with rare basolateral puncta remaining (Figure 2, G and H). Similar results were found for endogenous RME-1 detected by immunofluorescence with RME-1-specific antibodies (unpublished data). However, apical GFP-RME-1 appears normal or even enhanced in gum-1 mutants (Figure 2, I and J). Autofluorescent lysosome morphology was unchanged in gum-1 mutants (unpublished data).

The diffusion of RME-1 in gum-1 mutants could indicate a defect in recruiting RME-1 to basolateral recycling endosomes, or it could indicate a loss of basolateral recycling endosomes altogether (and thus a loss of RME-1-binding sites). The second model, in which early endosome to basolateral recycling endosome transport is blocked, might better explain the observed increase in early endosomes number in gum-1 mutants, because rme-1 null mutants do not accumulate increased numbers of early endosomes (Figure 2K and unpublished images).

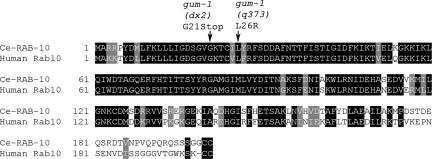

gum-1 Encodes the C. elegans RAB-10 Protein

Using standard methods we mapped gum-1 close to the right of bli-4 on chromosome I (see Materials and Methods). To determine which of the genes in this region corresponded to gum-1, we microinjected gum-1 mutants with wild-type C. elegans genomic DNA and assayed for rescue of the intestinal phenotype. We found that transgenic gum-1 mutants carrying cosmid clone T23H2 were fully rescued. We were able to narrow the rescuing activity to a 4-kb region containing only one predicted gene, T23H2.5, the C. elegans rab-10 gene, the apparent ortholog of human Rab10. We then confirmed that gum-1 is rab-10 by RNAi phenocopy of the intestinal vacuole phenotype and by identifying specific sequence changes in the rab-10 gene amplified from gum-1 mutant genomic DNA (see Materials and Methods). We identified a nonsense mutation in the dx2 allele resulting in a premature stop codon predicted to truncate the protein at amino acid 21. Thus dx2 is a predicted null allele of rab-10. We identified a missense mutation in the q373 allele resulting in a predicted amino acid change (L26R) in the conserved GTP-binding domain of RAB-10 that would be predicted to interfere with GTP binding, an essential feature of any Rab protein (Figure 3). Taken together these results showed that gum-1 is rab-10 and showed that the phenotypes we described above for gum-1(dx2) represent the null phenotype for rab-10 in C. elegans. Hereafter we refer to this gene as rab-10 to reflect its molecular nature.

Figure 3.

Amino acid alignment of Ce-RAB-10 and human Rab10. The C. elegans and human proteins share more than 90% amino acid identity outside of the hypervariable c-terminal domain. Mutations deduced from genomic sequencing of rab-10 mutants alleles dx2 and q373 are shown mapped onto the predicted protein sequence. Identical amino acids are shown in black.

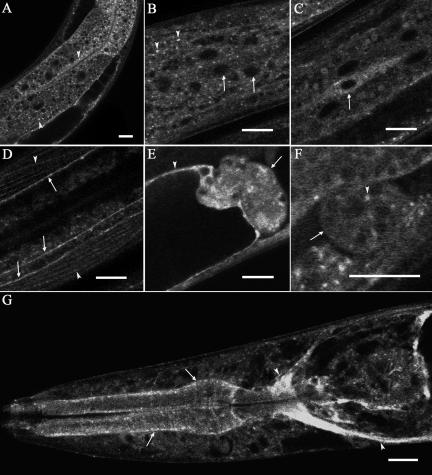

RAB-10 Is Broadly Expressed in C. elegans

To determine when and where rab-10 is normally expressed in C. elegans, we created transgenic animals expressing either GFP only, or a GFP-rab-10 fusion gene, driven by 2.9 kb of rab-10 upstream sequences (the predicted promoter region). We found that either of these constructs expressed almost ubiquitously. We observed expression in the intestine, hypodermis, seam cells, body-wall muscles and many neurons, oviduct sheath cell and spermatheca, coelomocytes, and pharyngeal and nerve ring (Figure 4, A–G). The GFP-RAB-10 fusion protein appeared punctate in most tissues. In the intestine GFP-RAB-10 localized to distinct cytoplasmic puncta resembling endosomes that ranged in size from 0.5 to 1.0 μm (Figure 4A, arrowheads). We found that the intestinal phenotype of rab-10(dx2) and rab-10(q373) was completely rescued by the GFP-RAB-10 fusion protein, indicating that the expression pattern and subcellular localization of the reporters very likely reflect those of the endogenous protein.

Figure 4.

RAB-10 is broadly expressed in C. elegans. Expression of a rescuing GFP-RAB-10 transgene driven by the rab-10 promoter is indicated in A, intestine, arrowheads indicate cytoplasmic puncta; in B, hypodermis, arrows indicate nucleus and arrowheads indicate cytoplasmic puncta; in C, seam cells (arrow); in D, nerve cord (arrow) and body-wall muscle (arrowhead); in E, spermatheca (arrow) and oviduct sheath cells (arrowhead); in F coelomocyte (arrow) and cytoplasmic puncta (arrowhead); and in G, pharynx (arrow) and nerve ring (arrowhead). Bar, 10 μm.

The rab-10-mutant Phenotype Can Be Rescued by GFP-Ce-RAB-10 or GFP-Human Rab10 Fusion Proteins Expressed under the Control of an Intestine-specific Promoter

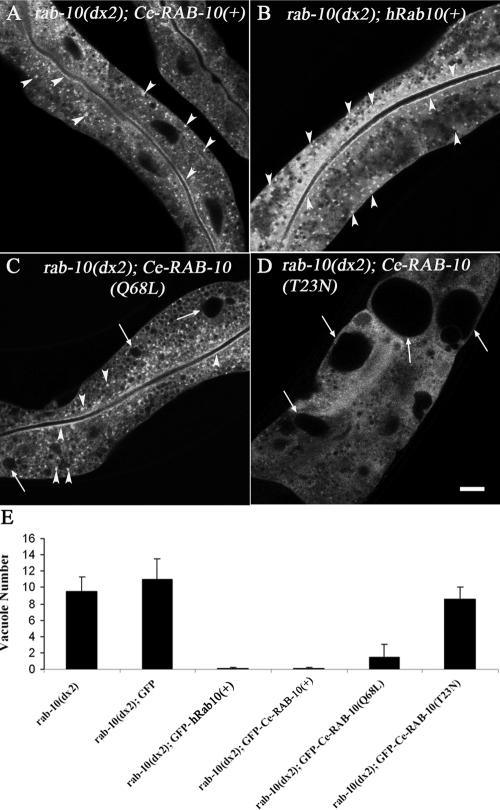

We also sought to determine if RAB-10 functions cell autonomously in the intestine and if the human Rab10 protein (hRab10) can substitute for worm RAB-10 in vivo. Toward this end we created transgenic worms expressing GFP-tagged C. elegans RAB-10 or human Rab10 driven by an intestine-specific promoter derived from the vha-6 gene (Oka et al., 2001). We then assayed the rescuing ability and subcellular localization of GFP-Ce-RAB-10 and GFP-hRab10 fusion proteins after crossing them into a rab-10(dx2) null mutant background. Rescue was assayed quantitatively by counting the number of abnormal intestinal vacuoles. GFP alone expressed in the intestine of rab-10(dx2) mutant worms was used a baseline control. We found that the rab-10 mutant intestinal phenotype was fully rescued by intestine-specific expression of GFP-Ce-RAB-10 or GFP-hRab10, indicating that RAB-10 functions autonomously in the intestine and that human Rab10 is a true ortholog of C. elegans RAB-10 (Figure 5, A, B, and E).

Figure 5.

GFP-tagged Ce-RAB-10 or GFP-tagged human Rab10 can rescue the intestinal phenotype of rab-10 null mutants. (A–D) Confocal images of intestines in the rab-10(dx2) strain expressing GFP-tagged Ce-RAB-10 or human Rab10. (A) rab-10(dx2) is rescued by expression of GFP-Ce-RAB-10 driven by the intestine-specific vha-6 promoter. (B) rab-10(dx2) is rescued by expression of GFP-human Rab10 driven by the vha-6 promoter. (C) rab-10(dx2) is partially rescued by expression of GFP-Ce-RAB-10(Q68L) driven by the vha-6 promoter. (D) rab-10(dx2) is not rescued by expression of GFP-Ce-RAB-10(T23N) or GFP alone (unpublished data) driven by the vha-6 promoter. Arrowheads indicate punctate endosomes and apical plasma membrane. Arrows indicate vacuoles with reduced sizes (C) or enlarged sizes (D). (E) Quantification of vacuoles in rescue experiments. Rescue efficiency was determined by counting vacuoles in transgenic young adult animals (n = 10 each). Bar, 10 μm.

In addition, we tested the importance of the predicted GTP binding and GTP hydrolysis activities of Ce-RAB-10 for in vivo function. Taking advantage of the well-studied biochemistry of ras/rab family GTPases, we engineered specific mutations into RAB-10 in the context of the vha-6 promoter-driven GFP-RAB-10 construct. We engineered point mutations into the construct that would be predicted to lock RAB-10 into the GDP-bound conformation (T23N) or the GTP-bound conformation (Q68L) and assayed the ability of the two mutant forms of RAB-10 to rescue rab-10(dx2) null mutant. We also compared the subcellular localization of the two mutant forms of RAB-10 with that of the wild-type form. The endosomes labeled by Ce-GFP-RAB-10 or hRab10 proteins appeared as strong puncta throughout the cytoplasm and more weakly as a line just below the apical membrane (Figure 5, A and B, arrowheads). Interestingly we found that the predicted GTP-locked (predicted GTPase defective) form of GFP-RAB-10 (Q68L) also displayed strong punctate labeling, indicating an association with membranes as expected and displayed partial rescuing activity (Figure 5, C and E). In addition, the GDP-bound form of GFP-RAB-10 (T23N) lacked rescuing activity completely and appeared diffuse in the cytoplasm (Figure 5, D and E). These results indicate that GTP-binding, and a normal GDP/GTP cycle, are important for RAB-10 function and its localization to membranes in vivo. In a wild-type background neither of these predicted dominant forms of GFP-RAB-10 had sufficient interfering activity to produce obvious vacuoles similar to those found in rab-10 loss of function mutants (unpublished data).

RAB-10 Is Associated with Endosomes and Golgi in the Intestine

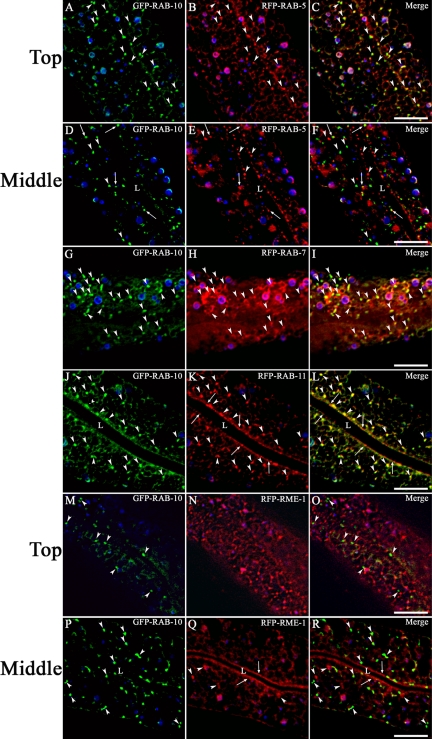

To determine where RAB-10 is normally localized and to help test the hypothesis that RAB-10 functions directly in endocytic transport, we performed a series of colocalization studies using rescuing GFP-tagged-RAB-10 and a set of RFP-tagged endosomal markers very similar to the GFP markers described above. GFP-RAB-10 did not colocalize with RFP-RME-1 on basolateral recycling endosomes (Figure 6, M–R). However we did find that a specific subset of intestinal GFP-RAB-10-labeled puncta colocalize very well with a subset of the early endosomes marked with RFP-RAB-5 (Figure 6, A–C). Most of the puncta positive for GFP-RAB-10 and RFP-RAB-5 are located very close to the basal PM and are best observed in the “Top” focal plane. Very few RAB-10 and RAB-5 double-positive structures were found in the “Middle” focal planes that offer better views of the medial and apical membranes (Figure 6, D–F). We also observed colocalization of GFP-RAB-10 with the early/late endosomal marker RFP-RAB-7, but the RAB-7 labeling of these structures was weaker (Figure 6, G–I).

Figure 6.

RAB-10 colocalizes with endosome markers in the intestine. (A–F) Colocalization of GFP-RAB-10 with early endosomal marker RFP-RAB-5. Images of the TOP focal plane (A–C) show basolateral membranes, whereas images of the MIDDLE focal plane (D–F) show the intestine in cross-section. Puncta labeled by both GFP-RAB-10 and RFP-RAB-5 are indicated by arrowheads (A–C) or arrows (D–F). Puncta labeled by GFP-RAB-10 or RFP-RAB-5 only but not both markers are indicated by arrowheads in D–F. (G–I) Colocalization of GFP-RAB-10 with early/late endosomal marker RFP-RAB-7. Arrowheads indicate puncta labeled by both GFP-RAB-10 and RFP-RAB-7. (J–L) Colocalization of GFP-RAB-10 with marker RFP-RAB-11. Arrowheads indicate medial puncta labeled by both GFP-RAB-10 and RFP-RAB-11. Arrows indicate apical puncta labeled by RFP-RAB-11. (M–R) Lack of colocalization of GFP-RAB-10 and RFP-RME-1. Arrowheads indicate puncta labeled only by GFP-RAB-10 or RFP-RME-1 and arrows indicate apical intestine labeled by RFP-RME-1. “L” indicates the position of the intestinal lumen. Bar, 10 μm. In each image autofluorescent lysosomes can be seen in all three channels with the strongest signal in blue, whereas GFP appears only in the green channel and RFP only in the red channel. Signals observed in the green or red channels that do not overlap with signals in the blue channel are considered bone fide GFP or RFP signals, respectively. Bar, 10 μm.

Unlike RFP-RAB-5, which primarily colocalized with GFP-RAB-10 near the basal and lateral PM, RFP-RAB-11 extensively colocalized with GFP-RAB-10 in puncta of the medial cytoplasm (Figure 6, J–L, arrowheads). These results indicate that the medially localized RAB-10-positive structures are likely to be Golgi and/or apical recycling endosomes. We also observed localization of both GFP-RAB-10 and RFP-RAB-11 very near the apical PM (Figure 6, J–L, arrows).

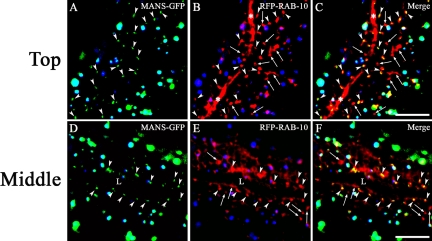

Given previously published reports that mammalian Rab10 is Golgi localized (Chen et al., 1993) and given our own observations showing extensive colocalization of GFP-RAB-10 with RFP-RAB-11, we next tested RAB-10 for Golgi localization using a specific C. elegans Golgi marker alpha-mannosidase II-GFP (MANS-GFP; Rolls et al., 2002; Figure 7, A–F). Unlike vertebrate cells that contain one large juxtanuclear Golgi stack, most invertebrate cells such as those in C. elegans instead contain many small Golgi stacks per cell, with the individual “mini-stacks” dispersed throughout the cytoplasm (Figure 7, A and D). Although the size and shape of the Golgi “mini-stacks” marked by MANS-GFP were different from the puncta labeled by RFP-RAB-10 (Figure 7, B and E), most medially located RFP-RAB-10-labeled structures overlapped with or were found directly adjacent to MANS-GFP labeled Golgi (Figure 7, C and F). These results indicate that many of the medially located RAB-10-labeled structures are likely to be Golgi associated structures, probably TGN.

Figure 7.

RFP-RAB-10 partially colocalizes with a Golgi marker (MANS-GFP) in the intestine. Images of the TOP focal plane (A–C) show basolateral membranes and cortex, whereas images of the MIDDLE focal plane (D–F) show the intestine in cross-section. Arrowheads indicate overlapping signals generated by MANS-GFP and RFP-RAB-10. Arrows indicate puncta positive for RFP-RAB-10 only. The asterisk (*) indicates the lateral plasma membrane and “L” indicates the position of apical lumen of the intestine. Bar, 10 μm.

Taken together these results are consistent with RAB-10 residing on a subset of basolateral early endosomes, where it could participate directly in basolateral cargo recycling. These results also indicate a significant residence of RAB-10 on TGN and/or apical recycling endosomes, where it could perform additional functions in secretion and/or apical recycling.

DISCUSSION

RAB-10 Is Required for Endocytic Recycling in the Worm Intestine

Here we present the first in vivo studies of rab-10 function in any organism and demonstrate a requirement for rab-10 in endocytic recycling. In C. elegans we found that expression of human Rab10 completely rescues the intestinal phenotype caused by loss of endogenous RAB-10 and that the distribution of human Rab10 within worm cells is quite similar to that of C. elegans RAB-10, establishing that the two proteins are functionally interchangeable and are true orthologues. Thus our studies of worm RAB-10 are very likely to be highly applicable to understanding Rab10 function in mammalian systems. The intestinal phenotype caused by loss of rab-10 is very similar to that caused by loss of rme-1, a known endocytic recycling factor (Grant et al., 2001; Lin et al., 2001). However, unlike rme-1 mutants that also display obvious endocytic defects in oocytes and coelomocytes, we did not detect endocytic defects in oocytes or coelomocytes in rab-10 mutant worms. Because our expression studies indicate that RAB-10 is broadly expressed, this lack of phenotype in other tissues likely indicates a redundancy in function for RAB-10, perhaps with another Rab protein, in at least some nonintestinal tissues.

C. elegans intestinal cells are polarized epithelial cells with distinct apical and basolateral membrane compartments and thus display an increased complexity of membrane trafficking processes compared with nonpolarized cells. In this more complex context there may be less redundancy in the trafficking pathways such that loss of individual components such as RAB-10 lead to more severe trafficking defects than occurs in nonpolarized cells.

In rab-10 mutants, as in rme-1 mutants, fluid-phase markers taken up through basolateral endocytosis accumulate in grossly enlarged endosomes. Endocytic tracers taken up by apical endocytosis never label these enlarged endosomes (unpublished data), suggesting that they are specifically of basolateral origin. The accumulation of endocytic tracers in these enlarged endosomes indicates that the internalization step of endocytosis is not significantly impaired in rab-10 mutants, but rather the recycling of the fluid back to the body cavity is defective. We also found that basolaterally localized transmembrane cargo proteins thought to be endocytosed by both clathrin-mediated and clathrin-independent mechanisms label the enlarged endosomes, consistent with the proposal that rab-10, like rme-1, regulates endocytic recycling but not endocytosis per se and that clathrin-dependent and clathrin-independent cargo are likely to meet in the endosomal system, as has been suggested in mammalian cell systems (Naslavsky et al., 2004; Weigert et al., 2004). Because all exogenous tracers that we have identified for studying endocytosis in C. elegans are sent to lysosomes when internalized apically but not recycled back to the intestinal lumen, we have not been able to determine if rab-10 or rme-1 mutations also affect apical recycling in the worm intestine. The only currently available transmembrane marker for the apical intestinal membrane is OPT-2, but it is not known if OPT-2 cycles through the apical endosomal system (Nehrke, 2003). In preliminary studies we find OPT-2-GFP to be normally localized in the intestine of rab-10 mutant worms (S. Vashist and B. D. Grant, unpublished results).

rab-10 May Regulate Transport between Basolateral Early and Recycling Endosomes

We took two additional approaches to determine the likely step in endocytic transport controlled by rab-10. First we analyzed the number and morphology of all major endosome classes in rab-10 mutant intestinal cells in vivo, using a set of GFP-tagged endosome markers. We expected that a kinetic block in a particular transport step caused by the lack of rab-10 would cause specific changes in endosome morphology. In general we expected that the RAB-10 donor compartment, or vesicles derived from that compartment, would become more numerous and/or enlarged in cells lacking RAB-10. We also expected that the target compartment, which normally receives cargo in a RAB-10-dependent manner, might be lost altogether and/or become smaller in size in cells lacking RAB-10. In fact we found that endosomes positive for RAB-5 and RAB-7 became more numerous and occasionally formed enormous endosomes (Supplementary Figure S3 and unpublished data), consistent with a block in export from the early endosomes. Conversely, the only compartment to become lost or greatly diminished was the RME-1-positive basolateral recycling endosomes. Taken together these results imply that transport from early endosomes to recycling endosomes is defective in rab-10 null mutants. An alternative view of these findings could be that RAB-10 functions with RME-1 in basolateral recycling endosome to PM transport and that RAB-10 functions to recruit RME-1 to endosomal membranes. We favor the first model where RAB-10 functions one step earlier than RME-1, because loss of RAB-10 leads to an abnormal accumulation of early endosomes, but loss of RME-1 does not lead to an abnormal accumulation of early endosomes, and because we could identify RAB-10 on early endosomes but not basolateral recycling endosomes (see below).

Consistent with previous results indicating that RME-1 mediates a distinct later recycling step, from basolateral recycling endosomes to the plasma membrane, we found that rme-1 null mutants accumulated the same recycling cargo as rab-10 mutants, but unlike rab-10 mutants, the number and size of the RAB-5-, RAB-7-, or RAB-10-labeled early endosomes was unaffected. Likewise the grossly enlarged endosomes evident in rme-1 null mutants did not label with these early endosome markers.

RAB-10 Colocalizes with Endosome and Golgi Markers in Worm Intestinal Cells

As a second approach to determine a likely step in endocytic transport controlled by RAB-10, we compared the subcellular localization of a rescuing GFP-RAB-10 fusion protein with a series of endosomal markers fused to RFP in the intestine of live animals. We found that a subset of the GFP-RAB-10-labeled puncta colocalize very well with a subset of the puncta labeled with early endosome markers.

Medially localized GFP-RAB-10 showed extensive colocalization with medially localized RFP-RAB-11, a marker of Golgi and ARE, and MANS-GFP, a marker of Golgi ministacks, consistent with previously published evidence that Rab10 associates with Golgi in CHO cells and sea urchin embryos (Chen et al., 1993; Leaf and Blum, 1998). Finally GFP-RAB-10 weakly labeled structures very near the apical PM, similarly to RFP-RAB-11 and RFP-RME-1, further suggesting possible association of RAB-10 with the ARE. Such apical GFP-RAB-10 was often only visible when expressed in a rab-10 null mutant background, suggesting that apical RAB-10-binding sites are easily saturated.

These results suggest that C. elegans RAB-10 is associated with multiple compartments. In particular the localization of RAB-10 to the Golgi suggests a role for RAB-10 in secretion. Although we did not find evidence for basolateral (YP170-GFP) or apical (OPT-2-GFP) secretion defects in the rab-10 null mutant, we sometimes observed some retention of intestinal YP170-GFP after rab-10 RNAi (C. Chen, S. Vashist, B. D. Grant, unpublished observations). Such retention of the secretory reporter after rab-10 RNAi could indicate that rab-10 acts redundantly in secretion, such that removal of rab-10 alone has no effect, but additional depletion of one or more closely related Rab proteins by RNAi cross-over reveals a redundant requirement. Further analysis will be required to address this issue.

The lack of colocalization of basolateral RFP-RME-1 with any of the other compartment markers further supports our previous evidence that RME-1 localizes to a distinct basolateral recycling compartment. We did note however that in addition to the strong localization of GFP- or RFP-tagged RME-1 to basolateral endosomes, in live animals we could also detect weaker apical labeling with GFP- or RFP-tagged RME-1. Apical RME-1 partially overlaps with apical RAB-11, suggesting that some RME-1 is also present on the ARE (Z. Balklava and B. D. Grant, unpublished observations). This apical GFP-RME-1 is most clearly evident in live larvae, is less prominent in live adults, and is lost when animals are fixed and permeablized for immunofluorescence, which is the most likely reason we did not detect such labeling previously.

Comparisons with the Mammalian System

The worm intestine displays many of the defining characteristics of a polarized epithelium including well-defined apical and basolateral membrane domains separated by apical tight junctions that are thought to act as a molecular “fence.” The apical domain is actin-rich with prominent microvilli (Segbert et al., 2004). A well-defined subapical terminal web-rich in intermediate filaments and actin-binding proteins similar to that of mammalian intestinal epithelia is also present (Bossinger et al., 2004). In addition to the obvious role intestinal cells must play in the uptake and processing of nutrients and the subsequent distribution of those nutrients throughout the body, the worm intestine is also responsible for the synthesis and secretion of abundant lipoprotein complexes (yolk), a liverlike function (Kimble and Sharrock, 1983). Finally the worm intestine is the major site of fat storage in the form of lipid droplets and thus also serves an adiposelike function for the animal (Ashrafi et al., 2003). It is likely that all of these functions as well as additional unknown functions for these cells contributed to the evolution of the complex trafficking pathways present in this tissue.

At present it is not clear how closely the membrane trafficking pathways of the worm intestine and those of mammalian polarized epithelial cells parallel one another, although our analysis of endomembrane markers presented here indicates significant similarity, including an apical compartment in the worm intestine that is highly enriched in RAB-11, a marker for the mammalian ARE (Casanova et al., 1999). One unique aspect of endomembrane organization in polarized MDCK cells is the presence of a common endosome that receives recycling or transcytotic cargo from both PM domains, which it then resorts for delivery to basolateral or apical membranes (Brown et al., 2000; Wang et al., 2000). In polarized MDCK cells GFP-Rab10 is enriched on the common endosomes (C. Babbey and K. Dunn, personal communication). In this study we show that RAB-10 in C. elegans localizes to several compartments including a basolaterally localized compartment enriched in RAB-5, a standard marker for early endosomes. In addition we observed strong RAB-10 labeling of a medial compartment positive for RAB-11 and mannosidase, likely the worm TGN. Finally RAB-10 is often visible very close to the apical PM in close proximity to RAB-11, possibly labeling the ARE. One possibility is that the medially localized and/or apical compartments positive for RAB-10 and RAB-11 are involved in apico-basal sorting, although we cannot currently test this without identifying apically recycling cargo in the worm intestine. However in rab-10 mutants we did not observe any steady missorting of apical cargo (OPT-2-GFP) to the basolateral membrane or missorting of basolateral cargo (YP170-GFP, hTAC-GFP, hTfR-GFP, or LMP-1-GFP) to the apical membrane.

Given our finding that human Rab10 can function in the context of the worm intestine, presumably recruiting and regulating endogenous effectors that mediate endocytic recycling, we anticipate that the molecular interactions that mediate RAB-10-dependent transport pathways in worms and humans are likely to be the same, and C. elegans genetics is likely to yield more important players in endocytic transport that are conserved among metazoans.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Hanna Fares for important reagents; Roger Y. Tsien for RFP plasmids; Kenneth Dunn for critical reading of this manuscript; Paul Fonarev for expert technical assistance; and Noriko Kane-Goldsmith and the W. M. Keck Center for Collaborative Neuroscience Imaging Facility for help with confocal microscopy. C.C. was partially supported by a Anne B. and James B. Leathem Scholarship Fund. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant GM67237 and March of Dimes Grant 5-FY02-252 to B.G. and NIH Grant GM49785 to E.J.L. B.G. also received support from the Chicago Community Trust Searle Scholars Program.

This article was published online ahead of print in MBC in Press (http://www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.E05–08–0787) on January 4, 2006.

The online version of this article contains supplemental material at MBC Online (http://www.molbiolcell.org).

References

- Altschuler, Y., Liu, S., Katz, L., Tang, K., Hardy, S., Brodsky, F., Apodaca, G., and Mostov, K. (1999). ADP-ribosylation factor 6 and endocytosis at the apical surface of Madin-Darby canine kidney cells. J. Cell Biol. 147, 7–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apodaca, G., Enrich, C., and Mostov, K. E. (1994a). The calmodulin antagonist, W-13, alters transcytosis, recycling, and the morphology of the endocytic pathway in Madin-Darby canine kidney cells. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 19005–19013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apodaca, G., Katz, L. A., and Mostov, K. E. (1994b). Receptor-mediated transcytosis of IgA in MDCK cells is via apical recycling endosomes. J. Cell Biol. 125, 67–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashrafi, K., Chang, F. Y., Watts, J. L., Fraser, A. G., Kamath, R. S., Ahringer, J., and Ruvkun, G. (2003). Genome-wide RNAi analysis of Caenorhabditis elegans fat regulatory genes. Nature 421, 268–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barroso, M., and Sztul, E. S. (1994). Basolateral to apical transcytosis in polarized cells is indirect and involves BFA and trimeric G protein sensitive passage through the apical endosome. J. Cell Biol. 124, 83–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besterman, J. M., Airhart, J. A., Woodworth, R. C., and Low, R. B. (1981). Exocytosis of pinocytosed fluid in cultured cells: kinetic evidence for rapid turnover and compartmentation. J. Cell Biol. 91, 716–727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bomsel, M., Prydz, K., Parton, R. G., Gruenberg, J., and Simons, K. (1989). Endocytosis in filter-grown Madin-Darby canine kidney cells. J. Cell Biol. 109, 3243–3258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bossinger, O., Fukushige, T., Claeys, M., Borgonie, G., and McGhee, J. D. (2004). The apical disposition of the Caenorhabditis elegans intestinal terminal web is maintained by LET-413. Dev. Biol. 268, 448–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner, S. (1974). The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 77, 71–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodsky, F. M., Chen, C. Y., Knuehl, C., Towler, M. C., and Wakeham, D. E. (2001). Biological basket weaving: formation and function of clathrin-coated vesicles. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 17, 517–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, P. S., Wang, E., Aroeti, B., Chapin, S. J., Mostov, K. E., and Dunn, K. W. (2000). Definition of distinct compartments in polarized Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells for membrane-volume sorting, polarized sorting and apical recycling. Traffic 1, 124–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burack, M. A., Silverman, M. A., and Banker, G. (2000). The role of selective transport in neuronal protein sorting. Neuron 26, 465–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caplan, S., Naslavsky, N., Hartnell, L. M., Lodge, R., Polishchuk, R. S., Donaldson, J. G., and Bonifacino, J. S. (2002). A tubular EHD1-containing compartment involved in the recycling of major histocompatibility complex class I molecules to the plasma membrane. EMBO J. 21, 2557–2567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casanova, J. E., Wang, X., Kumar, R., Bhartur, S. G., Navarre, J., Woodrum, J. E., Altschuler, Y., Ray, G. S., and Goldenring, J. R. (1999). Association of Rab25 and Rab11a with the apical recycling system of polarized Madin-Darby canine kidney cells. Mol. Biol. Cell 10, 47–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W., Feng, Y., Chen, D., and Wandinger-Ness, A. (1998). Rab11 is required for trans-golgi network-to-plasma membrane transport and is a preferential target for GDP dissociation inhibitor. Mol. Biol. Cell 9, 3241–3257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y. T., Holcomb, C., and Moore, H. P. (1993). Expression and localization of two low molecular weight GTP-binding proteins, Rab8 and Rab10, by epitope tag. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90, 6508–6512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clokey, G. V., and Jacobson, L. A. (1986). The autofluorescent “lipofuscin granules”in the intestinal cells of Caenorhabditis elegans are secondary lysosomes. Mech. Ageing Dev. 35, 79–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fares, H., and Greenwald, I. (2001a). Genetic analysis of endocytosis in Caenorhabditis elegans: coelomocyte uptake defective mutants. Genetics 159, 133–145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fares, H., and Greenwald, I. (2001b). Regulation of endocytosis by CUP-5, the Caenorhabditis elegans mucolipin-1 homologue. Nat. Genet. 28, 64–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagescu, R., Demaurex, N., Parton, R. G., Hunziker, W., Huber, L. A., and Gruenberg, J. (2000). The recycling endosome of madin-darby canine kidney cells is a mildly acidic compartment rich in raft components [In Process Citation]. Mol. Biol. Cell 11, 2775–2791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gesbert, F., Sauvonnet, N., and Dautry-Varsat, A. (2004). Clathrin-independent endocytosis and signalling of interleukin 2 receptors IL-2R endocytosis and signalling. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 286, 119–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant, B., and Hirsh, D. (1999). Receptor-mediated endocytosis in the Caenorhabditis elegans oocyte. Mol. Biol. Cell 10, 4311–4326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant, B., Zhang, Y., Paupard, M.-C., Lin, S. X., Hall, D. H., and Hirsh, D. (2001). Evidence that RME-1, a conserved C. elegans EH domain protein, functions in endocytic recycling. Nat. Cell Biol. 3, 573–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermann, G. J., Schroeder, L. K., Hieb, C. A., Kershner, A. M., Rabbitts, B. M., Fonarev, P., Grant, B. D., and Priess, J. R. (2005). Genetic analysis of lysosomal trafficking in Caenorhabditis elegans. Mol. Biol. Cell 16, 3273–3288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoekstra, D., Tyteca, D., and van IJzendoorn, S. C. (2004). The subapical compartment: a traffic center in membrane polarity development. J. Cell Sci. 117, 2183–2192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kauppi, M., Simonsen, A., Bremnes, B., Vieira, A., Callaghan, J., Stenmark, H., and Olkkonen, V. M. (2002). The small GTPase Rab22 interacts with EEA1 and controls endosomal membrane trafficking. J. Cell Sci. 115, 899–911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimble, J., and Sharrock, W. J. (1983). Tissue-specific synthesis of yolk proteins in C. elegans. Dev. Biol. 96, 189–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leaf, D. S., and Blum, L. D. (1998). Analysis of rab10 localization in sea urchin embryonic cells by three-dimensional reconstruction. Exp. Cell Res. 243, 39–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung, B., Hermann, G. J., and Priess, J. R. (1999). Organogenesis of the Caenorhabditis elegans intestine. Dev. Biol. 216, 114–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin, S. X., Grant, B., Hirsh, D., and Maxfield, F. R. (2001). Rme-1 regulates the distribution and function of the endocytic recycling compartment in mammalian cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 3, 567–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxfield, F. R., and McGraw, T. E. (2004). Endocytic recycling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 5, 121–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohrmann, K., Leijendekker, R., Gerez, L., and van Der Sluijs, P. (2002). rab4 regulates transport to the apical plasma membrane in Madin-Darby canine kidney cells. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 10474–10481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mostov, K., Su, T., and ter Beest, M. (2003). Polarized epithelial membrane traffic: conservation and plasticity. Nat. Cell Biol. 5, 287–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee, S., Ghosh, R. N., and Maxfield, F. R. (1997). Endocytosis. Physiol. Rev. 77, 759–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naslavsky, N., Weigert, R., and Donaldson, J. G. (2004). Characterization of a nonclathrin endocytic pathway: membrane cargo and lipid requirements. Mol. Biol. Cell 15, 3542–3552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nehrke, K. (2003). A reduction in intestinal cell pHi due to loss of the Caenorhabditis elegans Na+/H+ exchanger NHX-2 increases life span. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 44657–44666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, W. J., and Yeaman, C. (2001). Protein trafficking in the exocytic pathway of polarized epithelial cells. Trends Cell Biol. 11, 483–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols, B. (2003). Caveosomes and endocytosis of lipid rafts. J. Cell Sci. 116, 4707–4714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oka, T., Toyomura, T., Honjo, K., Wada, Y., and Futai, M. (2001). Four subunit a isoforms of Caenorhabditis elegans vacuolar H+-ATPase. Cell-specific expression during development. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 33079–33085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton, A., Knuth, S., Schaheen, B., Dang, H., Greenwald, I., and Fares, H. (2005). Endocytosis function of a ligand-gated ion channel homolog in Caenorhabditis elegans. Curr. Biol. 15, 1045–1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira-Leal, J. B., and Seabra, M. C. (2001). Evolution of the Rab family of small GTP-binding proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 313, 889–901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeffer, S., and Aivazian, D. (2004). Targeting Rab GTPases to distinct membrane compartments. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 5, 886–896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeffer, S. R. (1994). Rab GTPases: master regulators of membrane trafficking. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 6, 522–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Praitis, V., Casey, E., Collar, D., and Austin, J. (2001). Creation of low-copy integrated transgenic lines in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 157, 1217–1226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolls, M. M., Hall, D. H., Victor, M., Stelzer, E. H., and Rapoport, T. A. (2002). Targeting of rough endoplasmic reticulum membrane proteins and ribosomes in invertebrate neurons. Mol. Biol. Cell 13, 1778–1791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato, M., Sato, K., Fonarev, P., Huang, C. J., Liou, W., and Grant, B. D. (2005). Caenorhabditis elegans RME-6 is a novel regulator of RAB-5 at the clathrin-coated pit. Nat. Cell Biol. 7, 559–569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seabra, M. C., and Wasmeier, C. (2004). Controlling the location and activation of Rab GTPases. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 16, 451–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segbert, C., Johnson, K., Theres, C., van Furden, D., and Bossinger, O. (2004). Molecular and functional analysis of apical junction formation in the gut epithelium of Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev. Biol. 266, 17–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheff, D. R., Daro, E. A., Hull, M., and Mellman, I. (1999). The receptor recycling pathway contains two distinct populations of early endosomes with different sorting functions. J. Cell Biol. 145, 123–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timmons, L., and Fire, A. (1998). Specific interference by ingested dsRNA. Nature 395, 854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tooze, J., and Hollinshead, M. (1991). Tubular early endosomal networks in AtT20 and other cells. J. Cell Biol. 115, 635–653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treusch, S., Knuth, S., Slaugenhaupt, S. A., Goldin, E., Grant, B. D., and Fares, H. (2004). Caenorhabditis elegans functional orthologue of human protein hmucolipin-1 is required for lysosome biogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101, 4483–4488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullrich, O., Reinsch, S., Urbe, S., Zerial, M., and Parton, R. G. (1996). Rab11 regulates recycling through the pericentriolar recycling endosome. J. Cell Biol. 135, 913–924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Sluijs, P., Hull, M., Webster, P., Male, P., Goud, B., and Mellman, I. (1992). The small GTP-binding protein rab4 controls an early sorting event on the endocytic pathway. Cell 70, 729–740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Weert, A. W., Geuze, H. J., Groothuis, B., and Stoorvogel, W. (2000). Primaquine interferes with membrane recycling from endosomes to the plasma membrane through a direct interaction with endosomes which does not involve neutralisation of endosomal pH nor osmotic swelling of endosomes [In Process Citation]. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 79, 394–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, E., Brown, P. S., Aroeti, B., Chapin, S. J., Mostov, K. E., and Dunn, K. W. (2000). Apical and basolateral endocytic pathways of MDCK cells meet in acidic common endosomes distinct from a nearly-neutral apical recycling endosome. Traffic 1, 480–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weigert, R., Yeung, A. C., Li, J., and Donaldson, J. G. (2004). Rab22a regulates the recycling of membrane proteins internalized independently of clathrin. Mol. Biol. Cell 15, 3758–3770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamashiro, D. J., Tycko, B., Fluss, S. R., and Maxfield, F. R. (1984). Segregation of transferrin to a mildly acidic (pH 6.5) para-Golgi compartment in the recycling pathway. Cell 37, 789–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zerial, M., and McBride, H. (2001). Rab proteins as membrane organizers. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2, 107–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y., Grant, B., and Hirsh, D. (2001). RME-8, a conserved J-domain protein, is required for endocytosis in Caenorhabditis elegans. Mol. Biol. Cell 12, 2011–2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuk, P. A., and Elferink, L. A. (2000). Rab15 differentially regulates early endocytic trafficking. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 26754–26764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.