Abstract

Phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase, Pik1, is essential for viability. GFP-Pik1 localized to cytoplasmic puncta and the nucleus. The puncta colocalized with Sec7-DsRed, a marker of trans-Golgi cisternae. Kap95 (importin-β) was necessary for nuclear entry, but not Kap60 (importin-α), and exportin Msn5 was required for nuclear exit. Frq1 (frequenin orthologue) also is essential for viability and binds near the NH2 terminus of Pik1. Frq1-GFP localized to Golgi puncta, and Pik1 lacking its Frq1-binding site (or Pik1 overexpressed in frq1Δ cells) did not decorate the Golgi, but nuclear localization was unperturbed. Pik1(Δ10-192), which lacks its nuclear export sequence, displayed prominent nuclear accumulation and did not rescue inviability of pik1Δ cells. A Pik1-CCAAX chimera was excluded from the nucleus and also did not rescue inviability of pik1Δ cells. However, coexpression of Pik1(Δ10-192) and Pik1-CCAAX in pik1Δ cells restored viability. Catalytically inactive derivatives of these compartment-restricted Pik1 constructs indicated that PtdIns4P must be generated both in the nucleus and at the Golgi for normal cell function.

Introduction

Phosphatidylinositol (PtdIns) and derived molecules have crucial functions in eukaryotes, including yeast (Michell et al., 2003). PtdIns can be phosphorylated on certain hydroxyls in its head group by specific lipid kinases; phosphoinositides (PIPs) so generated can be hydrolyzed by various lipid phosphatases. PIPs, especially PtdIns4,5P2, can be cleaved by PLC, producing DAG and water-soluble inositol-1,4,5-P3 (IP3). IP3 can be acted on by other kinases and phosphatases to generate other inositol-phosphate species (IPxs). Thus, different membrane PIPs and soluble IPxs are well suited to serve as spatial and temporal regulators of diverse cellular processes.

The Saccharomyces cerevisiae genome encodes three PtdIns 4-kinase (PI4K) isoforms that generate PtdIns4P: Pik1 (Flanagan et al., 1993), Stt4 (Yoshida et al., 1994), and, Lsb6 (Han et al., 2002; Shelton et al., 2003). All are conserved from yeast to humans (for review see Heilmeyer et al., 2003). The mammalian Pik1 orthologue is PI4KIIIβ (Kapp-Barnea et al., 2003). Pik1 (120 kD) is soluble in cell extracts (Flanagan and Thorner, 1992) and Stt4 (215 kD) is localized in the plasma membrane (PM; Audhya and Emr, 2002). Each is essential for cell viability (Flanagan et al., 1993; Yoshida et al., 1994), indicating they serve nonoverlapping roles. Lsb6 (70 kD) is membrane associated, but dispensable, and is purported to function in endosome motility (Chang et al., 2005).

The first sst4 mutants were identified because they were hypersensitive to staurosporine, which is an inhibitor somewhat specific for PKC-related protein kinases (Yoshida et al., 1994). This phenotype is now understood. Pkc1 is essential for cell viability (Levin et al., 1990) and activated by the small GTPase, Rho1 (Kamada et al., 1996). Rho1 activation depends on the recruitment of its cognate guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) Rom2, which contains a PtdIns4,5P2-specific pleckstrin homology (PH) domain (Audhya and Emr, 2002). Stt4 generates the pool of PtdIns4P at the PM that is converted to PtdIns4,5P2 by the PtdIns4P 5-kinase, Mss4 (Desrivieres et al., 1998; Audhya and Emr, 2003). Thus, PtdIns4P serves as an intermediate in the generation of PtdIns4,5P2 and, in many eukaryotes (but not S. cerevisiae), PtdIns3,4,5P3, which each have been ascribed roles in actin dynamics, receptor-tyrosine kinase signaling, and endocytosis (Martin, 1998). However, compelling cumulative evidence, obtained first in yeast, shows that PtdIns4P itself has an important function in the Golgi (Hama et al., 1999; Walch-Solimena and Novick, 1999; Levine and Munro, 2002; Wang et al., 2003).

Genetic evidence implicates Pik1 in the synthesis of the Golgi pool of PtdIns4P. However, there is conflicting data concerning subcellular localization of Pik1. In cell lysates, the enzyme fractionates mainly like a soluble protein (Flanagan and Thorner, 1992; Huttner et al., 2003). Nevertheless, when examined by indirect immunofluorescence, epitope-tagged Pik1 localized to prominent cytosolic bodies, only some of which seemed congruent with a marker (Chs5) of the late Golgi (Schnieders, 1996; Walch-Solimena and Novick, 1999). In some cells, the nucleus was prominently stained (but it could not be discerned whether staining was inside or decorating the nuclear envelope). Yet another study that used an antibody of uncertain provenance and questionable utility for specific detection of Pik1, localized the protein exclusively to the nucleus upon subcellular fractionation (Garcia-Bustos et al., 1994). In contrast, a recent global analysis of yeast proteins using COOH-terminal GFP fusions concluded that Pik1 is localized uniformly in the cytosol (Huh et al., 2003). To further complicate matters, Pik1 binds and is positively regulated by the small, N-myristoylated, Ca2+-binding protein, Frq1 (frequenin/neuronal calcium sensor-1; Hendricks et al., 1999; Ames et al., 2000); however, the role of Frq1 in subcellular localization of Pik1 has not been explored.

Given the evidence that PIP-derived products have roles in the nucleus in both yeast (Odom et al., 2000) and animal cells (Irvine, 2003), the potential duality in Pik1 localization was intriguing, suggesting that, the essential functions of this enzyme may involve generation of PtdIns4P pools both at the Golgi and in the nucleus. To this end, and to better understand the mechanisms that control its subcellular localization, we first examined the intracellular distribution and dynamics of Pik1 in vivo using a fully functional GFP-Pik1 fusion, which revealed that Pik1 undergoes nucleocytoplasmic shuttling. We then used genetic approaches to discern the requirements for nuclear import and export of Pik1. Moreover, using appropriate mutants, we also analyzed the contributions that Frq1 makes to intracellular localization of Pik1. Finally, using strategies to restrict Pik1 to either the cytosolic or nuclear compartments, we investigated whether Pik1 serves essential physiological functions at the Golgi and in the nucleus and whether its PI4K activity is required in either organelle.

Results

Pik1 localizes to both the Golgi and the nucleus

Prior work (Hama et al., 1999; Walch-Solimena and Novick, 1999; Audhya et al., 2000) indicated that Pik1 function is needed for the Golgi-to-PM stage of secretion. At a restrictive temperature, pik1 ts mutants (but not isogenic PIK1 + cells) accumulate aberrant membranous structures (Fig. S1 A, available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200504104/DC1) that are similar in the EM to those accumulated by sec mutants blocked in Golgi-to-PM transport (Esmon et al., 1981; Fig. S1 B). The hypertrophied sacs that accumulate represent Golgi cisternae because they contain bona fide Golgi marker proteins, but not marker proteins of other compartments (Fig. S1 C). However, where Pik1 itself resides had not been resolved.

To examine subcellular localization in real time in live cells, GFP fusions were constructed. An NH2-terminal fusion (GFP-Pik1) was functional, as judged, first, by its stable expression that was determined by immunoblotting (unpublished data) and, second, by its ability to fully restore viability to pik1Δ cells (unpublished data). A COOH-terminal fusion (Pik1-GFP) was stable, but not functional. When expressed from the native PIK1 promoter on a low-copy (CEN) plasmid in a wild-type strain, GFP-Pik1 decorated numerous cytoplasmic puncta in the majority of cells (Fig. 1 A). To demonstrate that this compartment represents the Golgi, we exploited the properties of a chimera between a diagnostic marker for the late Golgi cisternae, Sec7 (Franzusoff et al., 1991), and Discosoma spp. red fluorescent protein (DsRed). Because DsRed tetramerizes, normally dispersed Golgi cisternae that contain Sec7-DsRed tend to clump into larger aggregates (Reinke et al., 2004). When GFP-Pik1 and Sec7-DsRed were coexpressed, GFP-Pik1 also clumped into a few large aggregates (Fig. 1 B, top left), just like Sec7-DsRed (Fig. 1 B, top right); and, both proteins colocalized in the majority of these clusters (Fig. 1 B, top left). Hence, the cytosolic puncta decorated by GFP-Pik1 are the Golgi itself.

Figure 1.

Pik1 localizes to cytoplasmic puncta enriched in a diagnostic Golgi marker. (A) Strain BY4743 carrying pTS8 was grown to mid-exponential phase at 30°C and examined by fluorescence microscopy (left) or Nomarski (DIC) optics (right). (B) Strain YTS114 expressing Sec7-DsRed (from the TRP1 locus) and GFP-Pik1 from pTS8 were grown to mid-exponential phase, immobilized in soft agar, and examined by fluorescence microscopy using band-pass filters optimized for the detection of GFP (top left) or DsRed (top right), and by Nomarski optics (bottom right). Overlay of the GFP and DsRed images is also shown (merge).

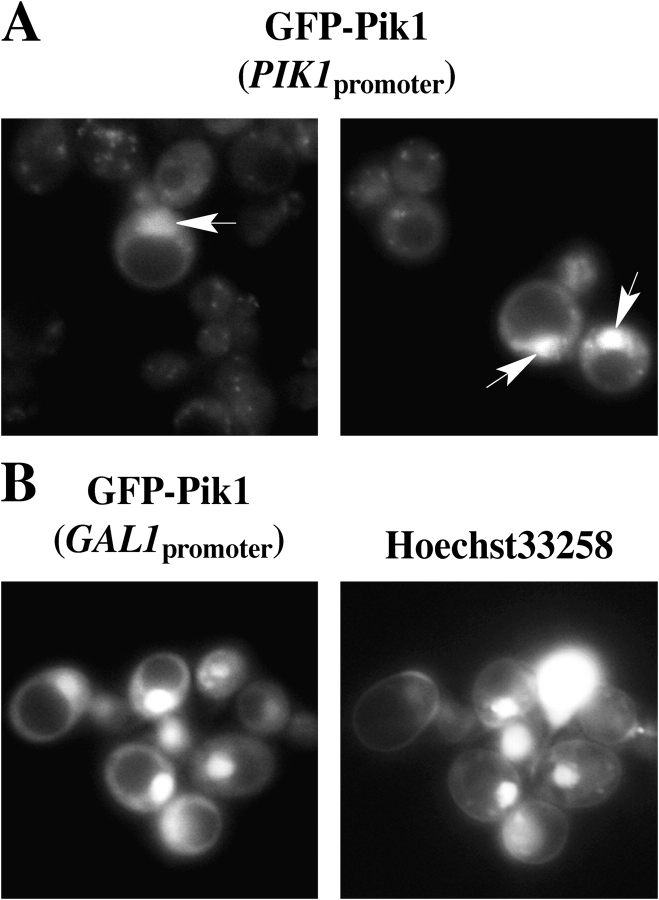

However, we noted consistently that, even when expressed at a near-endogenous level, GFP-Pik1 was found in the nucleus in 2–13% of the cells (depending on the strain examined; Fig. 2 A). No correlation between bud morphology and Pik1 distribution was seen, suggesting localization is not regulated by the cell cycle. When expression of GFP-Pik1 was elevated (Fig. 2 B), all cells displayed a very bright fluorescence that was congruent with the nucleus (stained with a vital DNA dye) and the cytosolic puncta were obscured by the general increase in cellular fluorescence.

Figure 2.

Pik1 is also a resident in the nucleus. (A) Two independent fields of the same culture that was described in Fig. 1 A. Some cells (typically those with the highest total fluorescence) exhibit a strong nuclear signal (arrows). (B) Strain BY4743 carrying pTS9 were induced with galactose for 3 h, counterstained for DNA with Hoechst 33258, and viewed under the fluorescence microscope with appropriate filters to visualize GFP (left) and the DNA dye (right).

Pik1 undergoes nucleocytoplasmic shuttling

The preceding results suggested that GFP-Pik1 is imported into the nucleus and, when overexpressed, accumulates there because its rate of entry exceeds its rate of export. Given its size, this nuclear import of GFP-Pik1 should require one (or more) of the known karyopherins (Strom and Weis, 2001). Therefore, we expressed GFP-Pik1 in strains carrying null mutations or temperature-sensitive alleles in all of the known importins. Nuclear accumulation of GFP-Pik1 was not impeded in mutants lacking any of the nonessential importins: Kap104, Sxm1, Mtr10, Kap114, Nmd5, Lph2, Pse1, Pdr6, and Yrb4 (unpublished data).

Kap60/Srp1/importin-α and Kap95/Rsl1/importin-β are each essential for viability. Typically, cargo proteins that use these karyopherins to enter the nucleus bind (via their NLS) to Kap60, which, in turn, binds to Kap95 (Enenkel et al., 1995). If Pik1 has an essential role in the nucleus, then these karyopherins may mediate its entry. In a kap60 ts mutant (Loeb et al., 1995), GFP-Pik1 still localized to the nucleus, even after a prolonged incubation at a restrictive temperature, which was no different from KAP60 + cells at the same high temperature (Fig. 3 A). In contrast, nuclear accumulation of GFP-Pik1 was largely abrogated in a kap95 ts mutant (Iovine and Wente, 1997), even at permissive temperature, whereas robust nuclear accumulation of GFP-Pik1 was seen in otherwise isogenic KAP95 + cells even at restrictive temperature (Fig. 3 B). Thus, although not unprecedented (Nikolaev et al., 2003), Pik1 is among the rare cargo whose nuclear import is mediated by Kap95 directly. Consistent with this conclusion, mutagenesis of the only close match in Pik1 to the classical NLS recognized by Kap60 (284KLPKRKPK291 to 284KLPKLLLK291) did not prevent its nuclear import or otherwise alter its intracellular distribution (unpublished data).

Figure 3.

Nuclear import of Pik1 requires importin-β, but not importin-α. (A) An importin-α (kap60 ts) mutant (YTS0012 srp1-31 ts) and its otherwise isogenic KAP60 + parent (W303-1a) carrying pTS7 were grown in SCRaf-Trp at 26°C to A600 nm ≈ 0.7, and a portion of each culture was shifted to 37°C. After 1 h, expression of GFP-Pik1 was induced by addition of galactose, and the cells were incubated for an additional 2 h at the indicated temperature before being inspected by fluorescence microscopy. (B) The identical experiment described in A was performed with an importin-β (kap95 ts) mutant (SWY1313 rsl1 ts) and its otherwise isogenic parent strain (SWY1312) carrying pTS7, except that, after galactose induction, the cells were incubated for 3 h at the indicated temperature before inspection.

For confirmation, the ability of Pik1 to associate directly with Kap95 was examined in vitro. Empty nickel agarose beads or beads coated with purified Kap95-His6 were incubated with the soluble fraction of extracts from yeast cells carrying an empty vector or expressing NH2 terminally c-Myc epitope–tagged Pik1 or a truncation, Pik1(Δ793-1066), lacking its catalytic domain. Bound proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting. No species cross-reactive with the anti-c-Myc (αMyc) mAb was detected in extracts from cells carrying vector alone (Fig. S2, top, lanes 2 and 5; bottom, lane 2). In contrast, ∼80% of the input mycPik1 bound to the Kap95-His6-coated beads, whereas <5% of the input mycPik1 bound to empty beads (Fig. S2, top panel, compare lane 1 with lane 4). Although expressed at a lower level (Fig. S2, bottom, compare lane 3 with lane 1), ∼80% of the input mycPik1(Δ793-1066) bound to the Kap95-His6 beads, whereas no detectable binding to empty beads was observed (Fig. S2, top, compare lane 3 with lane 6). Thus, Pik1 binds to Kap95 via an interaction site within its NH2-terminal regulatory domain.

Role of Frq1 in subcellular localization of Pik1

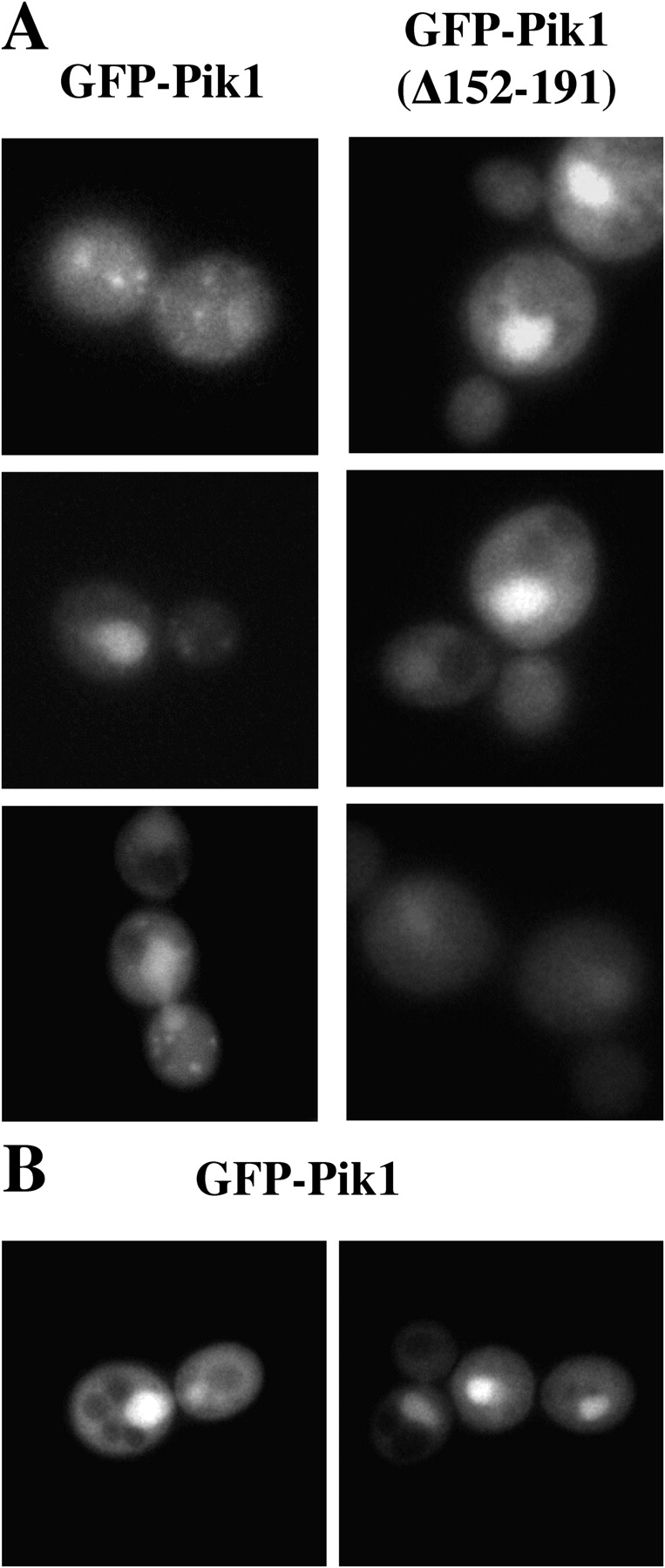

The NH2-terminal regulatory domain of Pik1 also contains a high-affinity binding site for Frq1, and Frq1 is required for optimal activity of Pik1 and for normal Pik1 function in vivo (Hendricks et al., 1999; Ames et al., 2000; Huttner et al., 2003). Based on its fractionation properties and its tight binding to Pik1, Frq1 might promote membrane interaction of Pik1, which lacks any known membrane-targeting motifs or domains. To determine whether Frq1 plays any role in subcellular localization of Pik1, we first examined a small deletion mutant, Pik1(Δ152-191), that retains considerable catalytic function (∼80% of wild-type Pik1), but lacks nearly all Frq1-binding activity (Huttner et al., 2003). Compared with GFP-Pik1, which displayed the expected distribution between the Golgi puncta and the nucleus (Fig. 4 A, left), GFP-Pik1(Δ152-191) showed a somewhat enhanced nuclear accumulation, diffuse cytoplasmic distribution, and never any detectable cytoplasmic puncta, even in cells expressing it at a low level (Fig. 4 A, right). As independent confirmation, we took advantage of the fact that inviability of frq1Δ cells can be rescued when Pik1 is highly overexpressed. Although overexpression tends to obscure visualization of the Golgi puncta, such bodies are still seen in a fraction of FRQ1 + cells where GFP-Pik1 is produced from the GAL1 promoter (not depicted), but never observed in frq1Δ cells (Fig. 4 B).

Figure 4.

Tethering of Pik1 at the Golgi requires Frq1. (A) Transformants of strain BY4743 carrying pTS9 and pTS10 to express either GFP-Pik1 (left) or GFP-Pik1(Δ152-191) (right), respectively, were induced with galactose for a brief period followed by shift to glucose to repress further expression, before viewing by fluorescence microscopy. (B) A frq1Δ null mutant (YKBH9) is shown harboring both YEp352GAL-PIK1 and pTS7, grown on galactose medium and viewed by fluorescence microscopy.

If Frq1 is required for Golgi recruitment of Pik1, then Frq1 itself should localize to the Golgi. Hence, Frq1 was tagged at its COOH terminus with GFP (because its NH2-terminal myristoyl group is important for its function) and was fully functional (unpublished data). Frq1-GFP displayed prominent cytoplasmic puncta, congruent with Sec7-DsRed (Fig. 5). As in pik1 ts mutants at restrictive temperature, secretion of invertase (Suc2) is largely blocked in frq1 ts mutants (even at permissive temperatures; Fig. S3 A, available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200504104/DC1) and aberrant Golgi-like structures are seen in frq1 ts cells at the restrictive temperature (Fig. S3 B). Thus, Frq1 plays a critical role in secretion because it is necessary for recruitment of Pik1 to the Golgi, but not for its nuclear import or export.

Figure 5.

Frq1-GFP localizes to Golgi puncta in the cytosol. Diploid strain YTS153, expressing FRQ1-GFP from its native promoter and integrated at its endogenous locus and SEC7-DsRed from the TPI1 promoter and integrated at the TRP1 locus, was grown and viewed by fluorescence microscopy, as in Fig. 1.

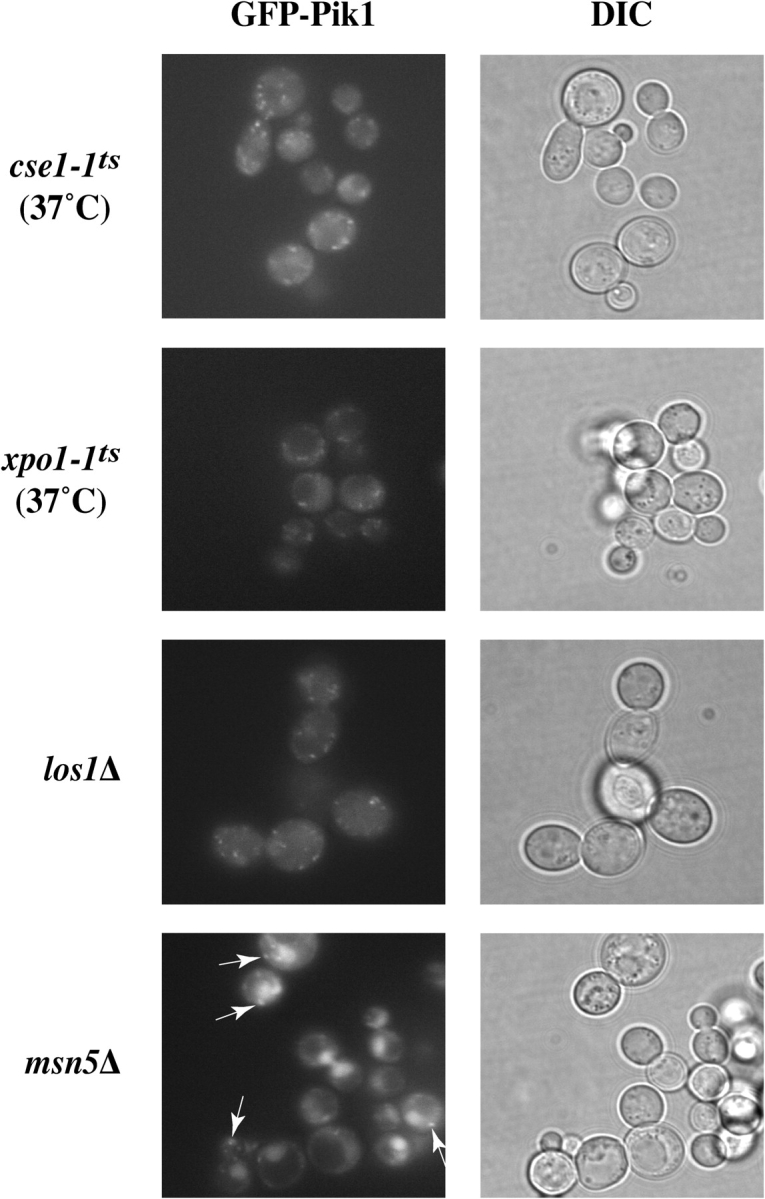

Nuclear export of Pik1 is dependent on Msn5

A hallmark of proteins that undergo continuous nucleocytoplasmic shuttling (as opposed to those bound and sequestered in the nucleus) is that they accumulate dramatically in the nucleus if the karyopherin responsible for their active export is removed. To demonstrate that Pik1 cycles between the nucleus and the cytosol and to identify the exportin responsible, we expressed GFP-Pik1 in strains that carry temperature-sensitive or null mutations in the four known exportins (Strom and Weis, 2001). No change in distribution of GFP-Pik1 was observed in cse1 ts or xpo1 ts mutants at the restrictive temperature, or in a los1Δ mutant under normal growth conditions (Fig. 6), or in the corresponding parental strains (not depicted). In contrast, a majority (≥70%) of msn5Δ cells displayed prominent nuclear accumulation of GFP-Pik1 (Fig. 6), but the isogenic MSN5 + parental strain did not (see Fig. 7). Thus, Pik1 continually shuttles between the nucleus and cytoplasm, and Msn5 mediates its nuclear export.

Figure 6.

Pik1 is exported from the nucleus in an Msn5-dependent manner. Strains carrying conditional or null mutations in the exportin genes indicated (see Table II), and their otherwise isogenic parental strains, were transformed with either pTS6 or pTS8, as necessary, and inspected by fluorescence microscopy. Pronounced nuclear accumulation occurred only in the msn5Δ mutant, but cytosolic puncta were also present (arrows).

Retention of Pik1 in the cytosol

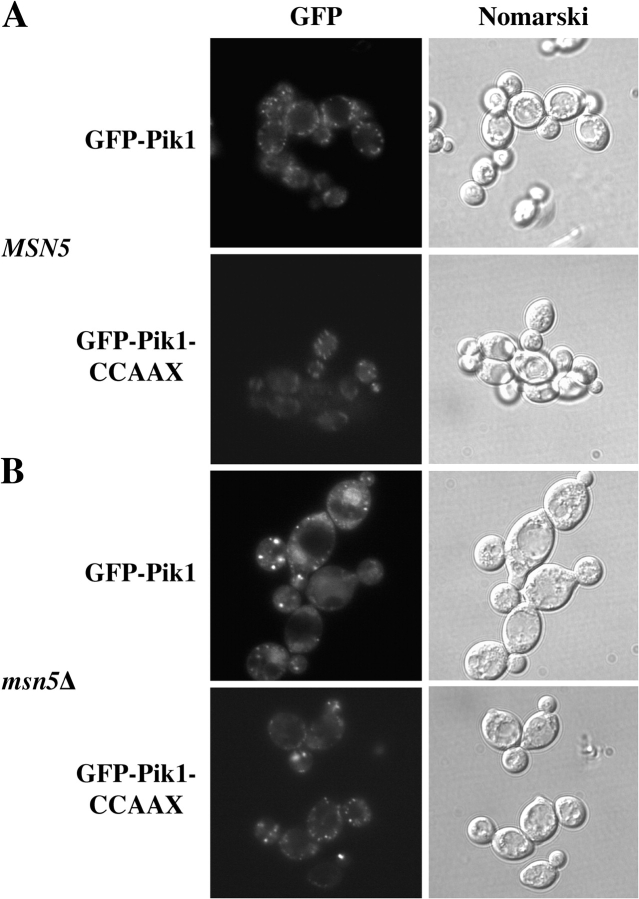

To test whether nuclear entry is essential for its function, we devised means to restrain Pik1 in the cytosol. There is no known consensus sequence for Kap60-independent, Kap95-dependent import. Hence, we exploited the COOH-terminal CCAAX motif of S. cerevisiae Ras2, which is S-prenylated, S-palmitoylated and carboxymethylated (Hancock, 2003) and serves as a constitutive membrane anchor (Pryciak and Huntress, 1998) that traffics proteins from the ER to the Golgi and then to the PM (Hancock, 2003). The five COOH-terminal residues of Pik1 (QGYIS-COOH) were replaced with the five COOH-terminal residues of Ras2 (CCIIS-COOH), designated Pik1-CCAAX. When expressed briefly from the GAL1 promoter on a CEN plasmid in normal cells, both GFP-Pik1 and GFP-Pik1-CCAAX decorated the Golgi puncta (although the latter was expressed at a somewhat lower level; Fig. 7 A), but GFP-Pik1-CCAAX was never observed in the nucleus, even upon prolonged expression from the GAL1 promoter (not depicted). When expressed in the same way in msn5Δ cells, GFP-Pik1 accumulated detectably in the nucleus, whereas GFP-Pik1-CCAAX did not (Fig. 7 B), confirming that GFP-Pik1-CCAAX does not enter the nucleus. Thus, attachment of the Ras2 CCAAX motif to the Pik1 COOH terminus did not interfere with Golgi localization, but prevented nuclear import.

Figure 7.

GFP-Pik1-CCAAX is restrained in the cytosol. A wild-type (MSN5 + /MSN5 +) diploid (BY4743) (A) and a homozygous msn5Δ/msn5Δ derivative (YTS002) (B) were transformed with pTS9 (GFP-Pik1) or pTS11 (GFP-Pik1-CCAAX), as indicated, grown to mid-exponential phase, induced with galactose for 45 min, returned to glucose medium to repress further expression, and were viewed in the fluorescence microscope (left) or under Nomarski optics (right) after 1 h.

Retention of Pik1 in the nucleus

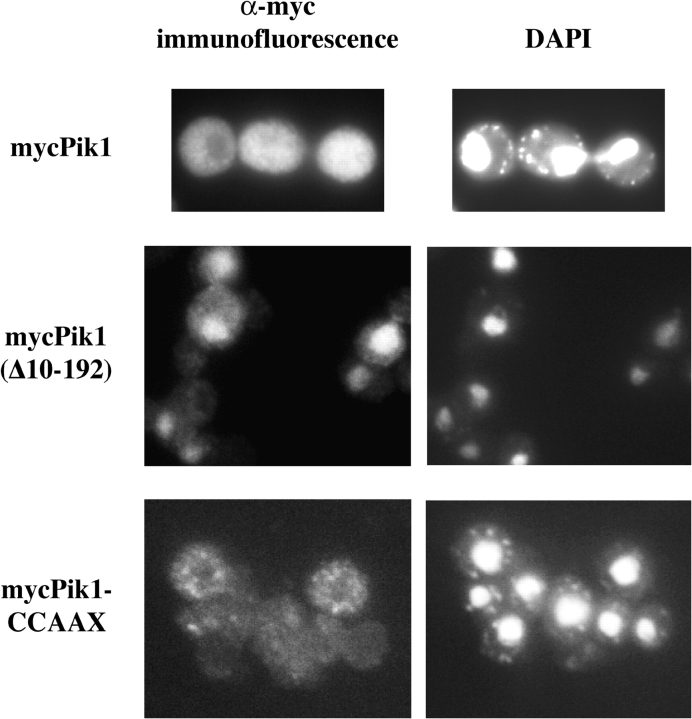

A 28-residue site (147–172) in Pik1 is necessary and sufficient for Frq1 binding (Huttner et al., 2003; Strahl et al., 2003), as judged by deletion mutants that remove these residues. To determine how such mutations affect subcellular localization, we examined Pik1 derivatives tagged with an NH2-terminal c-Myc epitope by indirect immunofluorescence. Generally, localization in fixed cells observed using the epitope-tagged constructs gave the same result as for GFP-Pik1 fusions in live cells, for example, GFP-Pik1-CCAAX (Fig. 7) and mycPik1-CCAAX (Fig. 8). A lack of the Frq1-binding site alone prevented Golgi targeting of GFP-Pik1 (Fig. 4 A) or mycPik1 (not depicted). A larger deletion, mycPik1(Δ10-192), compromised Golgi decoration, but also displayed prominent nuclear accumulation under conditions where mycPik1 did not (Fig. 8). Other deletions of a similar or greater size elsewhere, e.g., Pik1(Δ411-544), did not exhibit nuclear accumulation (unpublished data). No consensus for cargo recognition by Msn5 is known, yet Pik1(Δ10-192) must lack not only its Frq1-binding site, but also some sequence required for its Msn5-dependent export, confining it in the nucleus.

Figure 8.

Pik1(Δ10-192) accumulates in the nucleus. Diploid strain (BYB67) expressing from pRS314GAL-mycPIK1, pTS2 and pTS3, respectively, mycPik1 (top), mycPik1(Δ10-192) (middle) or mycPik1-CCAAX (bottom) were fixed and examined by indirect immunofluorescence using αMyc mAb 9E10 (left), after counterstaining with DAPI to reveal the nucleus (right).

Pik1 has essential functions inside and outside of the nucleus

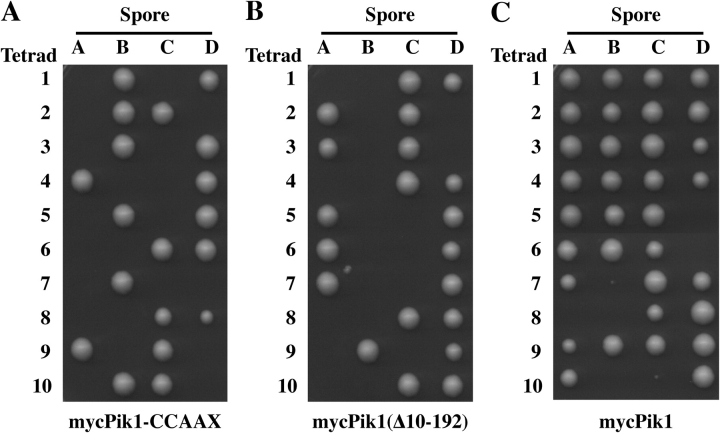

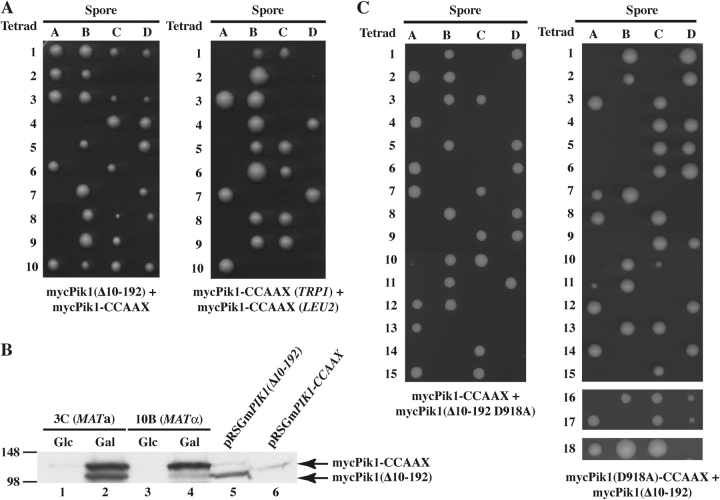

Pik1-CCAAX does not enter the nucleus, whereas Pik1(Δ10-192) accumulates in the nucleus. Hence, we examined whether Pik1 restricted to these compartments can provide its essential function, when present as the sole source of this enzyme. Each variant was expressed from the GAL1 promoter on a TRP1-marked CEN plasmid in a heterozygous pik1Δ::KanMX4/PIK1 + diploid. The resulting transformants were sporulated, and the tetrads were dissected on Gal medium at 26°C. If a Pik1 variant is functional, it permits growth of the otherwise inviable pik1Δ spores. Expression of mycPik1 rescued inviability of the pik1Δ spores because most tetrads yielded three or four viable colonies (Fig. 9 C) and many of the spore clones were both kanamycin (G418) resistant and Trp+ (not depicted). Neither mycPik1-CCAAX nor mycPik1(Δ10-192) supported growth of the pik1Δ spores because only two viable spores were produced from every tetrad (Fig. 9, A and B) and both spores were always G418-sensitive (not depicted).

Figure 9.

Neither Pik1-CCAAX nor Pik1(Δ10-192) can rescue the inviability of pik1 Δ cells. Heterozygous pik1Δ::KanMX4/PIK1 diploid strain (YTS68) was transformed with pTS3, pTS2 and pRS314GAL-mycPIK1 expressing, respectively, Myc-tagged Pik1-CCAAX (A), mycPik1(Δ10-192) (B), or mycPik1 (C). Each of the transformants was induced to undergo meiosis and sporulation, and the resulting tetrads were dissected and germinated on galactose medium. Spore clones (A–D) from 10 representative tetrads (1–10) of each strain are shown.

Failure to rescue pik1Δ spore viability could arise if Pik1-CCAAX and Pik1(Δ10-192) were expressed at a much lower level than normal Pik1; yet, immunoblotting indicated that mycPik1, mycPik1(Δ10-192), and mycPik1-CCAAX were produced at similar levels (Fig. S4, bottom; available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200504104/DC1). Another explanation could be that the modifications in Pik1-CCAAX or Pik1(Δ10-192) severely compromised catalytic activity. To examine this possibility, epitope-tagged proteins were recovered from extracts by immunoprecipitation and used as the enzyme source in in vitro PI4K assays. For cells expressing mycPik1, robust PtdIns4P production was found (Fig. S4, top, lane 1). A trace of PtdIns4P was generated when untagged Pik1 was overexpressed (Fig. S4, top, lane 2), presumably because, when a Myc-tagged protein is absent, some of the abundant untagged Pik1 binds nonspecifically to the c-Myc mAb-coated beads. This background disappeared when a Myc-tagged protein was present and Pik1 was at its endogenous level. For example, immunoprecipitation of a known catalytically inactive derivative, mycPik1(Δ302-785), produced no PtdIns4P (Fig. S4, top, lane 3). By contrast, mycPik1-CCAAX exhibited a specific activity indistinguishable from mycPik1 (Fig. S4, top, lane 5), whereas mycPik1(Δ10-192) displayed a specific activity about ∼10% of mycPik1 (Fig. S4, top, lane 4). Thus, the inability of Pik1(Δ10-192) to complement a pik1Δ mutation might be caused by its lower catalytic potency. However, several observations suggest that this is not the case. First, very low expression of normal Pik1, for example, from the GAL1 promoter under repressing conditions (i.e., on glucose medium) is sufficient to support the growth of pik1Δ cells (Schnieders, 1996). Second, expression of Pik1(Δ10-192) from the strong GAL1 promoter on a CEN plasmid is still unable to rescue the inviability of pik1Δ cells (Fig. 9).

As a further test that the inability of Pik1(Δ10-192) to complement is caused by its restricted compartmentalization and not its lower specific activity, mycPik1(Δ10-192) and mycPik1-CCAAX were coexpressed from the GAL1 promoter on differentially marked plasmids in the pik1Δ::KanMX4/PIK1 + diploid. GAL1-expressed mycPik1-CCAAX was introduced into the diploid on the two differentially marked plasmids as a control for the effect of elevated Pik1 level because of its expression from two separate plasmids. When nuclearly localized mycPik1(Δ10-192) was coexpressed with cytoplasmically localized mycPik1-CCAAX, the pik1Δ spores were able to survive, as judged by recovery of tetrads with three or four viable spores (Fig. 10 A), and Trp+ Leu+ KanR spores were recovered at a reasonable frequency (not depicted). As judged by immunoblotting, the viable Trp+ Leu+ KanR spores produced both mycPik1-CCAAX and mycPik1(Δ10-192), albeit sometimes not in equal proportions, and did so in a galactose-dependent manner (Fig. 10 B). Despite the fact that Pik1-CCAAX has a catalytic activity indistinguishable from wild-type Pik1, expression of this derivative alone from two different plasmids did not rescue inviability of the pik1Δ spores because only two viable (and both G418 sensitive) spore colonies were recovered in every tetrad (Fig. 10 A). Because only those pik1Δ spores that expressed Pik1 in both the nucleus and the cytosol survived, it suggests that discrete PtdIns4P pools must be generated for nuclear functions and for secretory transport. The data presented here demonstrate that this is normally achieved by nucleocytoplasmic shuttling of Pik1 and its Frq1-dependent tethering to the Golgi.

Figure 10.

Interallelic complementation of the inviability of pik1Δ cells by Pik1-CCAAX and Pik1(Δ10-192). (A) Heterozygous pik1Δ::KanMX4/PIK1 diploid (YTS68) cotransformed with either pTS2 and pTS4 expressing mycPik1(Δ10-192) and mycPik1-CCAAX (left) or pTS3 and pTS4 both expressing mycPik1-CCAAX (right) was sporulated and the resulting tetrads were dissected and germinated on galactose medium. Spore clones (A–D) from 10 representative tetrads (1–10) are shown. (B) Two representative G418-resistant colonies of opposite mating type were picked, propagated on galactose (Gal) or then shifted to glucose medium (Glc), and samples of the cultures were lysed and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with αMyc mAb 9E10. As markers, samples of lysates from cells expressing only mycPik1(Δ10-192) (lane 5) or mycPik1-CCAAX (lane 6) were examined. (C) Tetrad analysis, as in A, was conducted with YTS68 coexpressing either mycPik1-CCAAX and mycPik1(Δ10-192 D918A) (left) or mycPik1(D918A)-CCAAX and mycPik1(Δ10-192) (right).

To determine whether the PI4K activity of Pik1 is required for its function at the Golgi and in the nucleus, we mutated a residue (D918A) that is invariant in all PI4Ks (and PI3Ks). The crystal structure of a type IIβ PtdIns-phosphate kinase shows the equivalent position makes contact with both ATP and the substrate (Rao et al., 1998). The corresponding mycPik1(D918A), mycPik1(D918A)-CCAAX and mycPik1(Δ10-192 D918A) proteins were stably expressed (not depicted) and upon immunoprecipitation (Fig. S5 A, bottom, available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200504104/DC1) none of them displayed detectable PI4K activity, whereas mycPik1 displayed robust activity under the same conditions (Fig. S5 A, top). In addition, neither mycPik1(D918A) nor GFP-Pik1(D918A) was able to complement the inviability of pik1Δ spores (Fig. S5 B). Moreover, the mutation did not cause mislocalization because GFP-Pik1(D918A) was readily detectable both at Golgi puncta and in the nucleus (Fig. S5 C).

Finally, to determine whether Pik1 catalytic activity is needed for its essential functions in either compartment, either mycPik1-CCAAX and mycPik1(Δ10-192 D918A) or mycPik1(D918A)-CCAAX and mycPik1(Δ10-192) were coexpressed on differentially marked plasmids in the pik1Δ::KanMX4/PIK1 + diploid, which was subjected to tetrad analysis. For the former combination, only two viable (and G418-sensitive) spores were recovered from every tetrad (Fig. 10 C, left panel), indicating that the kinase activity of Pik1 is essential for its nuclear function. For the latter combination, the vast majority of the tetrads (∼90 total) also yielded only two viable (and G418-sensitive) spores; however, in each of three tetrads, one of the pik1Δ (KanR) spores was recovered and carried both plasmid markers (Leu+ and Trp+). Nonetheless, when subsequently propagated, these cells grew very slowly (especially on glucose, where wild-type Pik1 expressed from the GAL1 promoter supports a normal growth rate, even when repressed), appeared grossly enlarged, were highly vacuolated and/or accumulated apparent vesicular material in the cytosol (data not shown). Clearly, therefore, the kinase activity of Pik1 is also important for its function at the Golgi.

Discussion

This is the first comprehensive study of Pik1 localization in live cells. Our findings confirm our own prior observations (Schnieders, 1996; Hama et al., 1999) and those of others (Walch-Solimena and Novick, 1999; Sciorra et al., 2005), but significantly extend those conclusions and provide new insights about the factors that regulate subcellular localization of this PI4K. In particular, we demonstrated that Pik1 enters the nucleus and undergoes active nucleocytoplasmic shuttling. Moreover, we showed that a primary role of its tightly bound regulatory subunit, Frq1, is to assist with targeting of Pik1 to the cytoplasmic face of the Golgi. By preventing cycling of Pik1 between the nucleus and the cytosol and, conversely, by coexpressing Pik1 derivatives restricted to each of those compartments, we found that execution of the cellular functions of Pik1 requires its presence in catalytically active form both in the nucleus and at the Golgi.

Pik1 and Stt4 catalyze the same biochemical reaction, but play nonoverlapping roles, as deletion of either gene is lethal and overexpression of each gene cannot compensate for the loss of the other. This lack of redundancy is now explained by localization of each essential PI4K to distinct compartments: Stt4 to the PM (Audhya and Emr, 2002) and Pik1 at the Golgi and in the nucleus. Dual localization of Pik1 is not an artifact of overexpression because it was observed when cells expressed GFP-Pik1 from its own promoter on a low-copy-number vector. Moreover, nuclear entry of Pik1 was blocked by the loss of a specific importin (Kap95), and nuclear exit was blocked by the loss of a specific exportin (Msn5). But, we cannot exclude the possibility that other karyopherins may make minor contributions to nucleocytoplasmic transport of Pik1.

Cytosolic Pik1 localizes to the Golgi. Residence of Pik1 on this compartment is in accord with prior evidence that Pik1-generated PtdIns4P is important for efficient formation of Golgi-derived secretory vesicles destined for exocytosis at the PM (Hama et al., 1999; Walch-Solimena and Novick, 1999; Audhya et al., 2000). The Pik1-containing cytosolic puncta were identified as Golgi via colocalization with an Arf-GEF, Sec7, a well-accepted marker for this organelle in yeast (Franzusoff et al., 1991). Reportedly, Arf itself has a role in recruitment of PI4KIIIβ to the Golgi in tissue culture cells (Godi et al., 1999). Treatment of yeast cells with brefeldin A, which inhibits Sec7 GEF activity in vitro (Sata et al., 1998), causes aberrant Golgi to accumulate and blocks secretory transport (Chang et al., 2004), closely resembling the abnormal structures accumulated and the marked reduction in protein secretion seen in temperature-sensitive pik1 mutants at the restrictive temperature. However, we have no direct evidence that any yeast Arf involved in anterograde secretory transport is required for Pik1 function (unpublished data). Rather, as shown here, its regulatory subunit, Frq1, is targeted to the Golgi and is required for recruitment of Pik1 to the Golgi. Indeed, after our discovery of Frq1 as a permanently bound positive regulator of Pik1 in yeast (Hendricks et al., 1999), evidence has accumulated that its mammalian orthologue plays a similar role in localizing PI4KIIIβ at the Golgi (Bourne et al., 2001; Kapp-Barnea et al., 2003; Haynes et al., 2005).

PtdIns4P generated by Pik1 at the Golgi is not efficiently converted to PtdIns4,5P2 presumably because the PtdIns4P 5-kinase, Mss4, localizes to the PM and to the nucleus, but not to the Golgi (Desrivieres et al., 1998; Audhya and Emr, 2003). In addition, Inp53/Sjl3, a PIP 5-phosphatase that operates at the Golgi (Ha et al., 2003), may prevent inadvertent or premature conversion of PtdIns4P to PtdIns4,5P2 before secretory vesicles reach the PM. It is assumed that Pik1-generated PtdIns4P serves as a specific docking epitope on the Golgi membrane for recruitment of other proteins that are involved in vesicle formation and trafficking. Although certain yeast proteins have PH domains (Levine and Munro, 2002) and PH-like domains (Li et al., 2002) that mediate their Pik1-dependent and PtdIns4P-specific localization to the Golgi, these polypeptides are not individually required for secretion. Recently, an automated global screen for mutations synthetically lethal with a pik1 ts allele implicated Gyp2, the cognate GAP for a Golgi-specific Rab family member (Ypt31), as a potential candidate (Sciorra et al., 2005). Gyp2 contains a conserved GRAM domain (Doerks et al., 2000), which is a structural motif that resembles that of PH domains (Begley et al., 2003). Whether GRAM domains bind PIPs is, however, somewhat controversial (Begley et al., 2003). Moreover, mutations in the GRAM domain that make Gyp2 nonfunctional in vivo did not alter the subcellular distribution of GFP-Gyp2 nor is a gyp2Δ mutant inviable. Hence, the identity of the PtdIns4P-binding protein(s) required for secretion remains elusive.

In this regard, one study showed that PI4KIIIβ (but not its kinase activity) is necessary to recruit Rab11 (the mammalian Ypt31 orthologue) to the Golgi, and that this interaction is important for subsequent membrane traffic from the Golgi to the PM (de Graaf et al., 2004). However, in addition to the tagged PI4KIIIβ derivatives followed, catalytically active endogenous PI4KIIIβ was present in the same cells. In yeast, it is claimed that Lsb6 contributes to endosome motility independent of its own ability to generate PtdIns4P (Chang et al., 2005), but Stt4 at the PM could supply PIPs for endocytosis and control of actin dynamics.

In any event, it seems well established that one vital function of Pik1 is executed at the Golgi. However, as shown here, it is not sufficient for cell viability to restrain Pik1 to the cytosol or even to Golgi membranes. When expressed alone, Pik1-CCAAX, which is stable, fully catalytically active, present abundantly at the Golgi, and able to generate copious amounts of PtdIns4P at the Golgi—as judged by decoration with a PtdIns4P-specific reporter, GFP-2X-PH-domainOsh2 (Levine and Munro, 2002; unpublished data)—was unable to support the viability of pik1Δ cells. Thus, the essential functions of Pik1 are not confined to the Golgi and to the secretory process. Indeed, when Pik1-CCAAX was coexpressed with Pik1(Δ10-192) (which is only feebly active, unable to complement a pik1Δ mutation, and largely confined to the nucleus), the simultaneous presence of these two proteins was able to rescue the inviability of pik1Δ cells. When Pik1-CCAAX was coexpressed with catalytically inactive Pik1(Δ10-192), the cells were dead, confirming that PtdIns4P supplied by Pik1 in the nucleus is essential for cell function.

There is considerable evidence that PtdIns4,5P2 is present in the S. cerevisiae nucleus and is cleaved by the PLCδ1 orthologue, Plc1 (Flick and Thorner, 1993), to generate IP3 and other more highly phosphorylated IPxs derived from it, which have apparent roles in regulating mRNA export (York et al., 1999), modulating transcription (Odom et al., 2000) perhaps via chromatin-remodeling complexes (Shen et al., 2003; Steger et al., 2003), and influencing telomere length (York et al., 2005). Our results pinpoint Pik1 as the PI4K that is responsible for supplying the nuclear pool of PtdIns4P and, because Mss4 also traffics to the nucleus, at least some of this lipid is presumably converted to PtdIns4,5P2 to supply the substrate for Plc1. Like Pik1 and Mss4, Plc1 also undergoes active nucleocytoplasmic shuttling (Huynh, 1998). Thus, the cell brings the necessary machinery into the nucleus to ensure that these products are generated in situ. Given that IPxs are small enough to freely traverse the nuclear pore complex by passive diffusion, it is perhaps not surprising that generation of IPxs in the cytosol by contrived means is sufficient to support their nuclear functions (Miller et al., 2004). However, we find that when Plc1 is confined to the nucleus by point mutations that ablate its Xpo1-dependent nuclear export sequence, the rate and extent of IP3 production and generation of its more highly phosphorylated derivatives is elevated (unpublished data). Thus, most likely, soluble IPxs normally are generated locally within the nucleus via Plc1-dependent cleavage of the PtdIns4,5P2 supplied by Pik1 and Mss4 action.

However, plc1Δ mutants are viable (under nonstressful conditions; Flick and Thorner, 1993), whereas pik1Δ mutations are lethal under all conditions (Flanagan et al., 1993). Therefore, the PtdIns4P (and/or PtdIns4,5P2) derived from Pik1 action in the nucleus is not solely used as the substrate for Plc1, but must have some other essential function(s). Current evidence suggests that this essential role might be transcription. Mammalian tumor suppressor protein, ING2, is a member of a family of at least six, highly related chromatin-associated proteins and contains a plant homeodomain (PHD) motif that reportedly binds PtdIns4,5P2 and PtdIns5P (Gozani et al., 2003). Four close relatives of ING2 exist in the S. cerevisiae genome, all contain PHD motifs, and all are components of nuclear chromatin remodeling machines involved in gene regulation. Whether yeast PHD proteins bind PIPs is not known.

Also, tethering of transcription factors to integral membrane proteins on the inner face of the yeast nuclear envelope seems to have a critical role in regulating the expression of certain essential genes during the unfolded protein response and presumably during adaptation to other cellular stresses (Brickner and Walter, 2004). Perhaps Pik1-generated PIPs affect organization, stability, or function of the nuclear envelope proteins required for this transcriptional control. However, like other secretory blocks, shift of pik1 ts mutants to restrictive temperature induces robust UPR-lacZ reporter expression (unpublished data); hence, sustained Pik1-dependent PIP production is not needed, at least for the unfolded protein response. Potential involvement of Pik1-derived products in transcriptional regulation may be coupled to a perhaps related phenomenon. Certain proteins that reside in the nucleus rapidly relocalize to the cytosol when the secretory pathway is compromised (Nanduri et al., 1999). The so-called cell integrity MAPK signaling pathway initiated by Pkc1 is reportedly necessary for this response (Li et al., 2000; Nanduri and Tartakoff, 2001). When a secretion-defective mutant (sec6-4) was shifted to restrictive temperature for only 10 min, all nuclearly associated Pik1 was lost (Walch-Solimena and Novick, 1999). Hence, Pik1 may be a protein that rapidly relocalizes to the cytosol upon secretory stress. Nucleocytoplasmic shuttling of Pik1 may, therefore, be under regulation and Pik1 itself (or some component involved in its nucleocytoplasmic transport) may be a target of Pkc1 or of the MAPK (Mpk1/Slt2) it activates.

Materials and methods

Construction of plasmids

Plasmids (Table I) were constructed using standard recombinant DNA methods. Escherichia coli strains DH5α and NM522 were used to manipulate and propagate plasmids. PCR was performed using Pfu DNA polymerase (Stratagene); all constructs were verified by dideoxy chain termination sequencing. To produce kinase-dead Pik1, DNA fragments encoding a D918A mutation were generated by PCR using appropriate primers and incorporated by homologous recombination-mediated double strand break repair in vivo via cotransformation with acceptor vectors linearized with PflMI and BspEI (pTS12 and pTS16), BglII and BspEI (pTS13) or NheI and SacI (pTS15) in strain BJ2407. Plasmid DNA recovered from the resulting Leu+ or Trp+ transformants was rescued and amplified in E. coli. A YEp24-based plasmid encoding PEP4 (pBJ2802; gift of E.W. Jones, Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, PA) was used to allow sporulation of the protease-deficient diploid strain BJ2407. GEX2TK-KAP95-HIS 6 (gift of M. Rexach, Stanford University, Stanford, CA) was used to prepare GST-Kap95-His6 in E. coli.

Table I. Plasmids used in this study.

| Plasmid | Marker | Promoter | Insert | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| pRS314mycPIK1 | TRP1 | PIK1 | mycPIK1 | Hendricks et al., 1999 |

| pRS314GAL-mycPIK1 | TRP1 | PIK1 | mycPIK1 | Hendricks et al., 1999 |

| pTS12a | TRP1 | GAL1 | mycPIK1(D918A | This study |

| pTS1 | TRP1 | GAL1 | mycPIK1(Δ302-785) | This study |

| pTS2 | TRP1 | GAL1 | mycPIK1(Δ10-192) | This study |

| pTS13 | LEU2 | GAL1 | mycPIK1(Δ10-192) | This study |

| pTS14 | LEU2 | GAL1 | mycPIK1 (Δ10-192 D918A) | This study |

| pTS3 | TRP1 | GAL1 | mycPIK1-CCAAX | This study |

| pTS15 | TRP1 | GAL1 | mycPIK1(D918A)-CCAAX | This study |

| pTS4 | LEU2 | GAL1 | mycPIK1-CCAAX | This study |

| pRS314GAL-mycPIK1(Δ793-1066) | TRP1 | GAL1 | mycPIK1(Δ793-1066) | Hendricks et al., 1999 |

| pTS6 | TRP1 | PIK1 | GFP-PIK1 | This study |

| pTS7 | TRP1 | GAL1 | GFP-PIK1 | This study |

| pTS8 | LEU2 | PIK1 | GFP-PIK1 | This study |

| pTS9 | LEU2 | GAL1 | GFP-PIK1 | This study |

| pTS16 | LEU2 | GAL1 | GFP-PIK1(D918A) | This study |

| pTS10 | LEU2 | GAL1 | GFP-PIK1(Δ152-191) | This study |

| pTS11 | LEU2 | GAL1 | GFP-PIK1-CCAAX | This study |

| pFA6a-kanMX4 | kan r | TEV | KanMX4 | Longtine et al., 1998 |

| pFA6a-GFP(S65T)-kanMX6 | kan r | TEV | GFP(S65T)-KanMX6 | Longtine et al., 1998 |

| BJ2802 | URA3 | PEP4 | PEP4 | E.W. Jones |

| pGST-Kap95-His6 | AmpR | tac | GST-KAP95-His 6 | M. Rexach |

| YEp352GAL-PIK1 | URA3 | GAL1 | PIK1 | Hendricks et al., 1999 |

| YIplac204-T/C-SEC7-DsRed.T4 | TRP1 | TPI1 | SEC7-DsRed | Reinke et al., 2004 |

All pTS plasmids are based either on pRS314 (TRP1) or pRS315 (LEU2) (Sikorski & Hieter, 1989).

Yeast strains, growth conditions, and tetrad dissections

Yeast strains used in this study are listed in Table II. Standard rich (YP) and synthetic complete media (Sherman et al., 1986) were supplemented with either 2% glucose, 2% raffinose, or 2% galactose and with appropriate nutrients to maintain selection for plasmids. Yeast was cultivated at 30°C, unless otherwise stated. Standard methods for DNA-mediated transformation, sporulation, tetrad dissection, and other genetic manipulations of yeast cells were used (Guthrie and Fink, 1991). To generate a novel pik1 null allele, a KANMX4 cassette, flanked by short stretches (45 bp) of homology to sequences immediately upstream and downstream of the PIK1 coding region in the yeast genome, was amplified in a standard PCR reaction using pFA6a-KANMX4 as the template. The resulting DNA fragments were introduced by DNA-mediated transformation into strain BJ2407, and the cells were plated on YPD medium containing 200 μg/liter G418 sulfate (Mediatech Inc.). Candidate antibiotic-resistant integrants were restreaked on the same medium containing G418 and authentic transplacement of the PIK1 locus by the pik1Δ::KANMX4 allele on one homologue was verified by analytical PCR using appropriate primers. Strains YTS129 and YTS131 were generated in a similar manner, using strain BY4743 and appropriate primers to replace the PSE1 or MTR10 chromosomal loci, respectively, with a KANMX4 cassette. A one-step PCR-based technique for targeted modification of chromosomal loci (Longtine et al., 1998) was used to generate FRQ1-GFP. In brief, oligonucleotide primers with 5′-ends corresponding, respectively, to the last 40 bp of the FRQ1 ORF (forward) or to the first 40 bp downstream of the respective stop codons (reverse), and with 3′-ends to allow in-frame amplification of the GFP (S65T)-KanMX6 cassette, were used for PCR with pFA6a-GFP(S65T)-KanMX6 as the template. The resulting DNA products were purified, introduced by transformation into strain BY4743, and G418-resistant transformants were selected. Genomic DNA was prepared from candidate clones to verify its integration by homologous recombination at the FRQ1 locus and sequenced to confirm the integrity of the construct. For integration of YIplac204-T/C-SEC7-DsRed.T4, the plasmid was cut with Bsu36 I before transformation.

Table II. Strains used in this study.

| Strain | Genotype | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| BJ2168 | MAT a leu2 trp1 ura3-52 prb1-1122 prc1-40 pep4-3 gal2 | Jones, 1991 |

| CFY13 | hsc83Δ::LEU2 pep4Δ::URA3 (derived from BJ2168) | Flanagan and Thorner, 1992 |

| BJ2407 | MAT a /MATα (otherwise isogenic to BJ2168) | Jones, 1991 |

| YTS68 |

pik1Δ::KanMX4/PIK1 [pBJ2802] (otherwise isogenic to BJ2407) |

This study |

| YTS153 |

FRQ1-GFPkanMX6::FRQ1/FRQ1 SEC7-DsRed::TRP1/TRP1 (otherwise isogenic to BJ2407) |

This study |

| BY4743 |

MAT

a

/MATα his3-Δ1/his3-Δ1 leu2-Δ0/leu2-Δ0

lys2-Δ0/lys2-Δ0 ura3-Δ0/ura3-Δ0 |

Brachmann et al., 1998 |

| YTS001 | los1Δ/los1Δ (otherwise isogenic to BY4743) | Brachmann et al., 1998 |

| YTS002 | msn5Δ/msn5Δ (otherwise isogenic to BY4743) | Brachmann et al., 1998 |

| YTS005 | kap108Δ/kap108Δ (otherwise isogenic to BY4743) | Brachmann et al., 1998 |

| YTS006 | kap114Δ/kap114Δ (otherwise isogenic to BY4743) | Brachmann et al., 1998 |

| YTS007 | kap120Δ/kap120Δ (otherwise isogenic to BY4743) | Brachmann et al., 1998 |

| YTS008 | kap122Δ/kap122Δ (otherwise isogenic to BY4743) | Brachmann et al., 1998 |

| YTS009 | kap123Δ/kap123Δ (otherwise isogenic to BY4743) | Brachmann et al., 1998 |

| BY4741 | MAT a (otherwise isogenic to BY4743) | Brachmann et al., 1998 |

| YTS129 | pse1Δ::KanMX4 (otherwise isogenic to BY4741) | This study |

| YTS131 | mtr10Δ::KanMX4 (otherwise isogenic to BY4741) | This study |

| KWY12 | MAT a ade2-101 his3-11,15 trp1-Δ901 ura3-52 | Xiao et al., 1993 |

| KWY125 | cse1-1 (otherwise isogenic to KWY124) | Xiao et al., 1993 |

| BYB67 |

MAT

a/MATα ADE2/ade2-1 can1-100/can1-100

his3-11,15/his3-11,15 leu2-3,112/leu2-3,11 LYS2/lys2Δ::hisG trp1-1/trp1-1 ura3-1/ura3-1 (derived from W303) |

Shulewitz et al., 1999 |

| W303-1a | MAT a ade2-1 LYS2 (derived from W303) | Loeb et al., 1995 |

| KWY121 |

MATα ade2-1 LYS2 xpo1Δ::LEU2

[pKW457/pRS313-xpo1-1 ts] (otherwise isogenic to W303-1a) |

Stade et al., 1997 |

| YKBH9 | W303-1a [YEp352GAL-PIK1] | Hendricks et al., 1999 |

| RSY298 | sec7-1 ts (otherwise isogenic to W303-1a) | Esmon et al., 1981 |

| YTS001 | srp1-31 ts (otherwise isogenic to W303-1a) | Loeb et al., 1995 |

| YTS0010 |

MAT

a

his3-Δ200 leu2-3, 2-112 lys2-801 trp1-1

ura3-52 kap104Δ::URA3 |

Aitchison et al., 1996 |

| YTS0011 |

MATα his3-Δ200 leu2-3, 2-112 lys2-801 trp1-1

ura3-52 nmd5Δ::HIS3 |

Albertini et al., 1998 |

| SWY1312 | MAT a ade2-1 can1-100 his3-11,15 leu2-3,112 trp1-1 ura3-1 kap95Δ::HIS3 [pSW503/pRS315-KAP95] | Iovine and Wente, 1997 |

| SWY1313 | MAT a ade2-1 can1-100 his3-11,15 leu2-3,112 trp1-1 ura3-1 kap95Δ::HIS3 [pSW509/pRS315-kap95(L63A) ts] | Iovine and Wente, 1997 |

| YPH499 |

MAT

a

ade2-101

och his3-Δ200 leu2-Δ1 lys2-801am

trp1-Δ63 ura3-52 |

Sikorski and Hieter, 1989 |

| YKBH4 | frq1-1::HIS3 (otherwise isogenic to YPH499) | Hendricks et al., 1999 |

| YES32 | PIK1::TRP1 (otherwise isogenic to YPH499) | Schnieders, 1996 |

| YES102 | pik1-83::TRP1 (otherwise isogenic to YPH499) | Schnieders, 1996 |

| YTS114 |

prom

TPI1-SEC7-DsRed::TRP1 [pTS8] (otherwise isogenic to YPH499) |

This study |

| CTY1-1a | MAT a his3-Δ200 lys2-801 ura3-52 sec14-3 | Hama et al., 1999 |

Fluorescence microscopy and indirect immunofluorescence

To view GFP and/or DsRed fusion proteins, cells were grown to mid-exponential phase and examined directly under a fluorescence microscope equipped with appropriate band-pass filters for detection of each protein. To counterstain for DNA, cells were incubated in growth medium with 2 μg/ml Hoechst 33258 (Invitrogen) for 15 min before viewing. Unless otherwise noted, expression of GFP fusion proteins under control of the GAL1 promoter was induced by adding galactose (2% final concentration) to the culture and, after 45 min, glucose was added (2% final concentration) to repress further expression and the cells were grown for 1 h. To localize GFP-Pik1 in strains SWY1312 and SWY1313, cells first were grown at 26°C, shifted to 37°C for 1 h, and then galactose was added to induce GAL1 promoter-driven expression; after 3 h, the cells were viewed by fluorescence microscopy. To localize GFP-Pik1 in strains YTS0012 and W303-1a (kap60 ts and KAP60 +, respectively), cells were treated as just described, but incubated at 37°C for as long as 5 h after galactose induction.

BYB67 cells carrying plasmids for the GAL1 promoter-driven expression of either mycPik1, mycPik1(Δ10-192) or mycPik1-CCAAX were grown to A600 nm ≈ 0.5, induced by addition of galactose (2% final concentration) for 90 min, fixed, and prepared for indirect immunofluorescence. Cells were incubated with a solution (1 mg/ml) of affinity-purified αMyc mAb 9E10 that was diluted 1:150 in PBS, pH 7.3, containing 1 mg/ml BSA (PBSA) for 2 h at RT, washed three times with PBSA, and then incubated for 1 h with FITC-conjugated secondary antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) that was diluted 1:700 in PBSA. To counterstain for DNA, DAPI was added (1 μg/ml final concentration) during the last 2 min of incubation. Subsequently, cells were washed six times with PBS, mounted in Citifluor (Ted Pella Inc.), examined under either a Plan Apo 100×/1.4 oil objective on a fluorescence microscope (Eclipse TE300; Nikon) equipped with a charged-coupled device camera (Orca 100; Hamamatsu) and compatible software (Phase 3 Imaging Systems, Inc.) or a D Plan Apo UV 100×/1.3 oil objective on a BH-2 fluorescence microscope equipped with a MagnaFire SP charged-coupled device camera and software (Olympus).

Preparation of yeast cell extracts and immunoprecipitation

Yeast cell lysis, preparation of extracts, and immunoprecipitations were performed as described previously (Hendricks et al., 1999; Huttner et al., 2003).

Online supplemental material

Supplemental materials and methods section describes the following protocols: negative stain and immunogold EM; preparation of Kap95-His6 and in vitro binding studies; invertase secretion measurement; and measurement of PI4K activity. Fig. S1 shows aberrant membrane structures accumulated in pik1 ts mutants at restrictive temperature are hypertrophied cisternae enriched in Golgi marker proteins. Fig. S2 shows purified importin-β binds Pik1. Fig. S3 depicts a frq1 ts mutant is defective in secretory transport and accumulates aberrant membrane structures at restrictive temperatures. Fig. S4 shows that both Pik1-CCAAX and Pik1(Δ10-192) are catalytically active. Fig. S5 characterizes the catalytically inactive mutant, Pik1(D918A). Online supplemental material is available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200504104/DC1.

Acknowledgments

We thank J. Abbruzzese and W. McManus for assistance with performing EM, and B. Glick, K.B. Hendricks, E.W. Jones, S. Patel, M. Rexach, B.Q. Wang, K. Weis, and S. Wente for strains, plasmids, or advice.

This work was supported by a grant from the American Cancer Society and funds from the Utah Agricultural Experiment Station (to D.B. DeWald) and by the National Institutes of Health Research Grant GM21841, by a grant from the Lowe Syndrome Association, and by facilities provided by the Berkeley campus Cancer Research Laboratory (to J. Thorner).

H. Hama's present address is Dept. of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, SC 29425.

Abbreviations used in this paper: DsRed, Discosoma spp. red fluorescent protein; GEF, guanine nucleotide exchange factor; IP3, inositol-1,4,5-P3; IPxs, other inositol-phosphates; PH, pleckstrin homology; PI4K, PtdIns 4-kinase; PIP, phosphoinositide; PM, plasma membrane; PtdIns, phosphatidylinositol.

References

- Aitchison, J.D., G. Blobel, and M.P. Rout. 1996. Kap104p: a karyopherin involved in the nuclear transport of messenger RNA binding proteins. Science. 274:624–627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albertini, M., L.F. Pemberton, J.S. Rosenblum, and G. Blobel. 1998. A novel nuclear import pathway for the transcription factor TFIIS. J. Cell Biol. 143:1447–1455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ames, J.B., K.B. Hendricks, T. Strahl, I.G. Huttner, N. Hamasaki, and J. Thorner. 2000. Structure and calcium-binding properties of Frq1, a novel calcium sensor in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochemistry. 39:12149–12161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Audhya, A., and S.D. Emr. 2002. Stt4 PI 4-kinase localizes to the plasma membrane and functions in the Pkc1-mediated MAP kinase cascade. Dev. Cell. 2:593–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Audhya, A., and S.D. Emr. 2003. Regulation of PI4,5P2 synthesis by nuclear-cytoplasmic shuttling of the Mss4 lipid kinase. EMBO J. 22:4223–4236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Audhya, A., M. Foti, and S.D. Emr. 2000. Distinct roles for the yeast phosphatidylinositol 4-kinases, Stt4p and Pik1p, in secretion, cell growth, and organelle membrane dynamics. Mol. Biol. Cell. 11:2673–2689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begley, M.J., G.S. Taylor, S.-A. Kim, D.M. Veine, J.E. Dixon, and J.A. Stuckey. 2003. Crystal structure of a phosphoinositide phosphatase, MTMR 2, insights into myotubular myopathy and Charcot-Marie Tooth Syndrome. Mol. Cell. 12:1391–1402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourne, Y., J. Dannenberg, V. Pollmann, P. Marchot, and O. Pongs. 2001. Immunocytochemical localization and crystal structure of human frequenin (neuronal calcium sensor 1). J. Biol. Chem. 276:11949–11955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brachmann, C.B., A. Davies, G.J. Cost, E. Caputo, J. Li, P. Hieter, and J.D. Boeke. 1998. Designer deletion strains derived from Saccharomyces cerevisiae S288C: a useful set of strains and plasmids for PCR-mediated gene disruption and other applications. Yeast. 14:115–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brickner, J.H., and P. Walter. 2004. Gene recruitment of the activated INO1 locus to the nuclear membrane. PLoS Biol. 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Chang, F.S., G.-S. Han, G.M. Carman, and K.J. Blumer. 2005. A WASp-binding type II phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase required for actin polymerization-driven endosome motility. J. Cell Biol. 171:133–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang, H.J., S.A. Jesch, M.L. Gaspa, and S.A. Henry. 2004. Role of the unfolded protein response pathway in secretory stress and regulation of INO1 expression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 168:1899–1913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Graaf, P., W.T. Zwart, R.A.J. van Dijken, M. Deneka, T.K.F. Schulz, N. Geijsen, P.J. Coffer, B.M. Gadella, A.J. Verkleij, P. van der Sluijs, and P.M van Bergen en Henegouwen. 2004. Phosphatidylinositol 4-kinaseβ is critical for association of rab11 with the golgi complex. Mol. Biol. Cell. 15:2038–2047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desrivieres, S., F.T. Cooke, P.J. Parker, and M.N. Hall. 1998. MSS4, a phosphatidylinositol-4-phosphate 5-kinase required for organization of the actin cytoskeleton in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 273:15787–15793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doerks, T., M. Strauss, M. Brendel, and P. Bork. 2000. GRAM, a novel domain in glucosyltransferases, myotubularins, and other putative membrane-associated proteins. Trends Biochem. Sci. 25:483–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enenkel, C., G. Blobel, and M. Rexach. 1995. Identification of a yeast karyopherin heterodimer that targets import substrate to mammalian nuclear pore complexes. J. Biol. Chem. 270:16499–16502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esmon, B., P. Novick, and R. Schekman. 1981. Compartmentalized assembly of oligosaccharides on exported glycoproteins in yeast. Cell. 25:451–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flanagan, C.A., and J. Thorner. 1992. Purification and characterization of a soluble phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase from the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 267:24117–24125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flanagan, C.A., E.A. Schnieders, A.W. Emerick, R. Kunisawa, A. Admon, and J. Thorner. 1993. Phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase: gene structure and requirement for yeast cell viability. Science. 262:1444–1448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flick, J.S., and J. Thorner. 1993. Genetic and biochemical characterization of a phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 13:5861–5876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franzusoff, A., K. Redding, J. Crosby, R.S. Fuller, and R. Schekman. 1991. Localization of components involved in protein transport and processing through the yeast Golgi apparatus. J. Cell Biol. 112:27–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Bustos, J.F., F. Marini, I. Stevenson, C. Frei, and M.N. Hall. 1994. PIK1, an essential phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase associated with the yeast nucleus. EMBO J. 13:2352–2361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godi, A., P. Pertile, R. Meyers, P. Marra, G. Di Tullio, C. Iurisci, A. Luini, D. Corda, and M.A. De Matteis. 1999. ARF mediates recruitment of PtdIns-4-OH kinase-beta and stimulates synthesis of PtdIns(4,5)P-2 on the Golgi complex. Nat. Cell Biol. 1:280–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gozani, O., P. Karuman, D.R. Jones, D. Ivanov, J. Cha, A.A. Lugovskoy, C.L. Baird, H. Zhu, S.J. Field, S.L. Lessnick, et al. 2003. The PHD finger of the chromatin-associated protein ING2 functions as a nuclear phosphoinositide receptor. Cell. 114:99–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guthrie, C., and G.R. Fink. 1991. Guide to yeast genetics and molecular biology. Methods in Enzymology, vol. 194, ed. J.N. Abelson and M.I. Simon. New York: Academic Press, Inc. [PubMed]

- Ha, S.A., J. Torabinejad, D.B. DeWald, M.R. Wenk, L. Lucast, P. De Camilli, R.A. Newitt, R. Aebersold, and S.F. Nothwehr. 2003. The synaptojanin-like protein Inp53/Sjl3 functions with clathrin in a yeast TGN-to-endosome pathway distinct from the GGA protein-dependent pathway. Mol. Biol. Cell. 14:1319–1333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hama, H., E.A. Schnieders, J. Thorner, J.Y. Takemoto, and D.B. DeWald. 1999. Direct involvement of phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate in secretion in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 274:34294–34300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han, G.S., A. Audhya, D.J. Markley, S.D. Emr, and G.M. Carman. 2002. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae LSB6 gene encodes phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase activity. J. Biol. Chem. 277:47709–47718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hancock, J.F. 2003. Ras proteins: different signals from different locations. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 4:373–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haynes, L.P., G.M. Thomas, and R.D. Burgoyne. 2005. Interaction of neuronal calcium sensor-1 and ADP-ribosylation factor 1 allows bidirectional control of phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase beta and trans-Golgi network-plasma membrane traffic. J. Biol. Chem. 280:6047–6054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heilmeyer, L.M., Jr., G. Vereb Jr., G. Vereb, A. Kakuk, and I. Szivak. 2003. Mammalian phosphatidylinositol 4-kinases. IUBMB Life. 55:59–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendricks, K.B., B.Q. Wang, E.A. Schnieders, and J. Thorner. 1999. Yeast homologue of neuronal frequenin is a regulator of phosphatidylinositol-4-OH kinase. Nat. Cell Biol. 1:234–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huh, W.K., J.V. Falvo, L.C. Gerke, A.S. Carroll, R.W. Howson, J.S. Weissman, and E.K. O'Shea. 2003. Global analysis of protein localization in budding yeast. Nature. 425:686–691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huttner, I.G., T. Strahl, M. Osawa, D.S. King, J.B. Ames, and J. Thorner. 2003. Molecular interactions of yeast frequenin (Frq1) with the phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase isoform, Pik1. J. Biol. Chem. 278:4862–4874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huynh, C.V. 1998. Molecular genetic analysis of a phosphoinositide-specific phospholipase C (PLC1 gene product) in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Ph.D. thesis. University of California, Berkeley, Berkeley, CA. 173 pp.

- Iovine, M.K., and S.R. Wente. 1997. A nuclear export signal in Kap95p is required for both recycling the import factor and interaction with the nucleoporin GLFG repeat regions of Nup116p and Nup100p. J. Cell Biol. 137:797–811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irvine, R.F. 2003. Nuclear lipid signaling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 4:349–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones, E.W. 1991. Tackling the protease problem in yeast. Methods Enzymol. 194:428–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamada, Y., H. Qadota, C.P. Python, Y. Anraku, Y. Ohya, and D.E. Levin. 1996. Activation of yeast protein kinase C by Rho1 GTPase. J. Biol. Chem. 271:9193–9196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapp-Barnea, Y., S. Melnikov, I. Shefler, A. Jeromin, and R. Sagi-Eisenberg. 2003. Neuronal calcium sensor-1 and phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase beta regulate IgE receptor-triggered exocytosis in cultured mast cells. J. Immunol. 171:5320–5327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin, D.E., F.O. Fields, R. Kunisawa, J.M. Bishop, and J. Thorner. 1990. A candidate protein kinase C gene, PKC1, is required for the S. cerevisiae cell cycle. Cell. 62:213–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine, T.P., and S. Munro. 2002. Targeting of Golgi-specific pleckstrin homology domains involves both PtdIns 4-kinase-dependent and -independent components. Curr. Biol. 12:695–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, X., M.P. Rivas, M. Fang, J. Marchena, B. Mehrotra, A. Chaudhary, L. Feng, G.D. Prestwich, and V.A. Bankaitis. 2002. Analysis of oxysterol binding protein homologue Kes1p function in regulation of Sec14p-dependent protein transport from the yeast Golgi complex. J. Cell Biol. 157:63–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y., R.D. Moir, I.K. Sethy-Coraci, J.R. Warner, and I.M. Willis. 2000. Repression of ribosome and tRNA synthesis in secretion-defective cells is signaled by a novel branch of the cell integrity pathway. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:3843–3851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeb, J.D., G. Schlenstedt, D. Pellman, D. Kornitzer, P.A. Silver, and G.R. Fink. 1995. The yeast nuclear import receptor is required for mitosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 92:7647–7651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longtine, M.S., A. McKenzie III, D.J. Demarini, N.G. Shah, A. Wach, A. Brachat, A. Philippsen, and J.R. Pringle. 1998. Additional modules for versatile and economical PCR-based gene deletion and modification in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 14:953–961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin, T.F. 1998. Phosphoinositide lipids as signaling molecules: common themes for signal transduction, cytoskeletal regulation, and membrane trafficking. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 14:231–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michell, R.H., N.M. Perera, and S.K. Dove. 2003. New insights into the roles of phosphoinositides and inositol polyphosphates in yeast. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 31:11–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller, A.L., M. Suntharalingam, S.L. Johnson, A. Audhya, S.D. Emr, and S.R. Wente. 2004. Cytoplasmic inositol hexakisphosphate production is sufficient for mediating the Gle1-mRNA export pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 279:51022–51032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nanduri, J., and A.M. Tartakoff. 2001. The arrest of secretion response in yeast: signaling from the secretory path to the nucleus via Wsc proteins and Pkc1p. Mol. Cell. 8:281–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nanduri, J., S. Mitra, C. Andrei, Y. Liu, Y. Yu, M. Hitomi, and A.M. Tartakoff. 1999. An unexpected link between the secretory path and the organization of the nucleus. J. Biol. Chem. 274:33785–33789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikolaev, I., M.F. Cochet, and B. Felenbok. 2003. Nuclear import of zinc binuclear cluster proteins proceeds through multiple, overlapping transport pathways. Eukaryot. Cell. 2:209–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odom, A.R., A. Stahlberg, S.R. Wente, and J.D. York. 2000. A role for nuclear inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate kinase in transcriptional control. Science. 287:2026–2029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pryciak, P.M., and F.A. Huntress. 1998. Membrane recruitment of the kinase cascade scaffold protein Ste5 by the Gβ-γ complex underlies activation of the yeast pheromone response pathway. Genes Dev. 12:2684–2697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao, V.D., S. Misra, I.V. Boronenkov, R.A. Anderson, and J.H. Hurley. 1998. Structure of type IIβ phosphatidylinositol phosphate kinase: a protein kinase fold flattened for interfacial phosphorylation. Cell. 94:829–839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinke, C.A., P. Kozik, and B.S. Glick. 2004. Golgi inheritance in small buds of Saccharomyces cerevisiae is linked to endoplasmic reticulum inheritance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 101:18018–18023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sata, M., J.G. Donaldson, J. Moss, and M. Vaughan. 1998. Brefeldin A-inhibited guanine nucleotide-exchange activity of Sec7 domain from yeast Sec7 with yeast and mammalian ADP ribosylation factors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 95:4204–4208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnieders, E.A. 1996. Biochemical and genetic analysis of a phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase (PIK1 gene product) in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Ph.D. thesis. University of California, Berkeley, Berkeley, CA. 185 pp.

- Sciorra, V.A., A. Audhya, A.B. Parsons, N. Segev, and C. Boone. 2005. Synthetic genetic array analysis of the PtdIns 4-kinase Pik1p identifies components in a Golgi-specific Ypt31/rab-GTPase signaling pathway. Mol. Biol. Cell. 16:776–793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelton, S.N., B. Barylko, D.D. Binns, B.F. Horazdovsky, J.P. Albanesi, and J.M. Goodman. 2003. Saccharomyces cerevisiae contains a Type II phosphoinositide 4-kinase. Biochem. J. 371:533–540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen, X., H. Xiao, R. Ranallo, W.H. Wu, and C. Wu. 2003. Modulation of ATP-dependent chromatin-remodeling complexes by inositol polyphosphates. Science. 299:112–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman, F., G.R. Fink, and J.A. Hicks. 1986. Appendix A. In Laboratory Course Manual for Methods in Yeast Genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. Cold Spring Harbor, NY. 163–167.

- Shulewitz, M.J., C.J. Inouye, and J. Thorner. 1999. Hsl7 localizes to a septin ring and serves as an adapter in a regulatory pathway that relieves tyrosine phosphorylation of Cdc28 protein kinase in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:7123–7137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sikorski, R.S., and P. Hieter. 1989. A system of shuttle vectors and yeast host strains designed for efficient manipulation of DNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 122:19–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stade, K., C.S. Ford, C. Guthrie, and K. Weis. 1997. Exportin 1 (Crm1p) is an essential nuclear export factor. Cell. 90:1041–1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steger, D.J., E.S. Haswell, A.L. Miller, S.R. Wente, and E.K. O'Shea. 2003. Regulation of chromatin remodeling by inositol polyphosphates. Science. 299:114–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strahl, T., B. Grafelmann, J. Dannenberg, J. Thorner, and O. Pongs. 2003. Conservation of regulatory function in calcium-binding proteins: Human frequenin (neuronal calcium sensor-1) associates productively with yeast phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase isoform, Pik1. J. Biol. Chem. 278:49589–49599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strom, A.C., and K. Weis. 2001. Importin-beta-like nuclear transport receptors. Genome Biol 10.1186/gb-2001-2-6-reviews3008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Walch-Solimena, C., and P. Novick. 1999. The yeast phosphatidylinositol-4-OH kinase Pik1 regulates secretion at the Golgi. Nat. Cell Biol. 1:523–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.J., J. Wang, H.Q. Sun, M. Martinez, Y.X. Sun, E. Macia, T. Kirchhausen, J.P. Albanesi, M.G. Roth, and H.L. Yin. 2003. Phosphatidylinositol 4 phosphate regulates targeting of clathrin adaptor AP-1 complexes to the Golgi. Cell. 114:299–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Z., J.T. McGrew, A.J. Schroeder, and M. Fitzgerald-Hayes. 1993. CSE1 and CSE2, two new genes required for accurate mitotic chromosome segregation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 13:4691–4702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- York, J.D., A.R. Odom, R. Murphy, E.B. Ives, and S.R. Wente. 1999. A phospholipase C-dependent inositol polyphosphate kinase pathway required for efficient messenger RNA export. Science. 285:96–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- York, S.J., B.N. Armbruster, P. Greenwell, T.D. Petes, and J.D. York. 2005. Inositol diphosphate signaling regulates telomere length. J. Biol. Chem. 280:4264–4269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida, S., Y. Ohya, M. Goebl, A. Nakano, and Y. Anraku. 1994. A novel gene, STT4, encodes a phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase in the PKC1 protein kinase pathway of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 269:1166–1172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]