Abstract

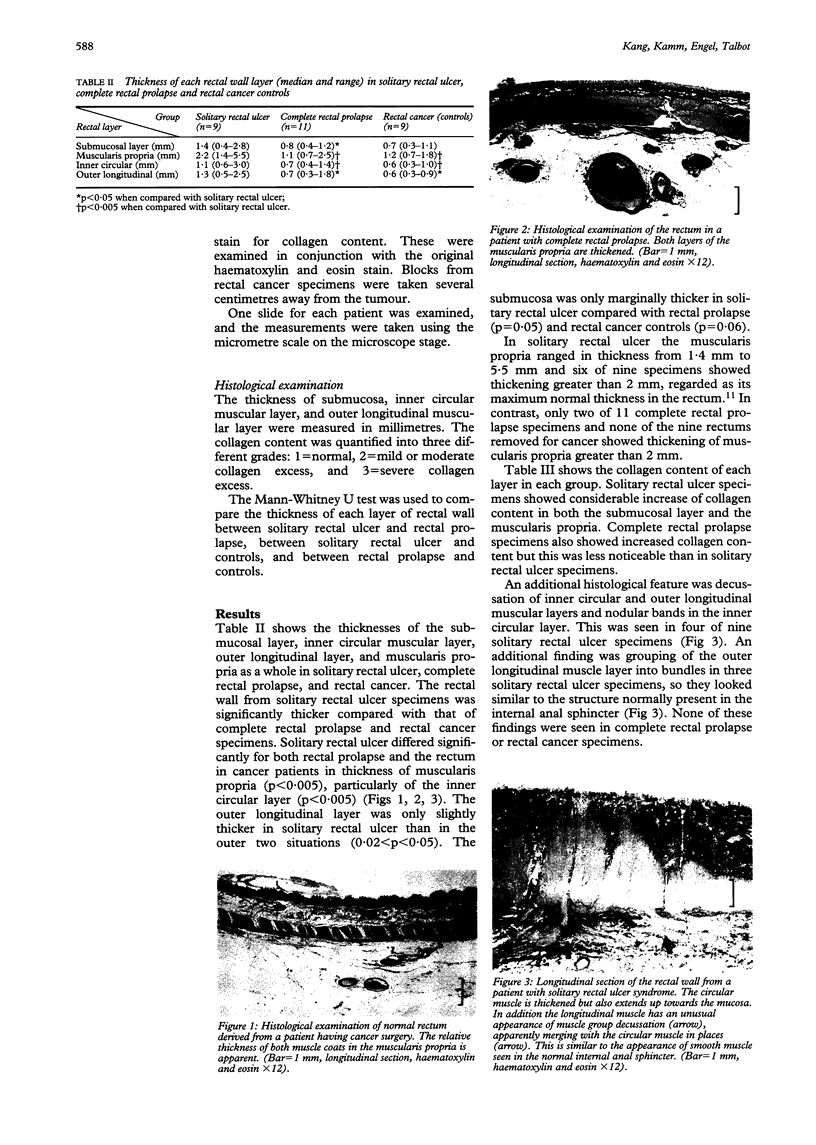

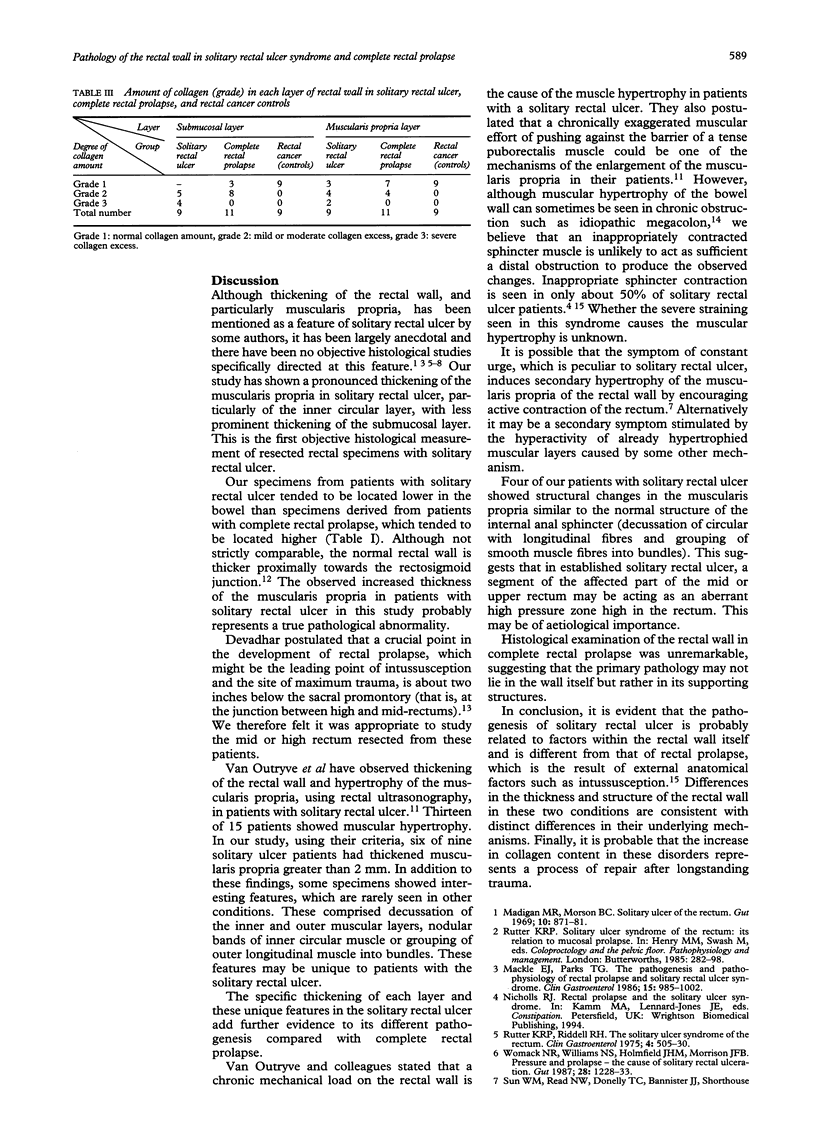

BACKGROUND--The aetiology and pathology of rectal prolapse and solitary rectal ulcer are poorly understood. AIMS--To examine the full thickness rectal wall in these two conditions. METHODS--The pathological abnormalities in the surgically resected rectal wall were studied from nine patients with solitary rectal ulcer syndrome, 11 complete rectal prolapse, and nine cancer controls. Routine haematoxylin and eosin and Van Gieson staining for collagen were performed. RESULTS--The rectal wall from solitary rectal ulcer syndrome specimens was thickened compared with complete rectal prolapse and controls. The major difference was in the muscularis propria (2.2 v 1.1 v 1.2 mm, medians, p < 0.005) and particularly the inner circular muscular layer, and to a lesser extent the submucosal and outer longitudinal muscular layers. Some solitary rectal ulcer syndrome specimens showed unique features such as decussation of the two muscular layers (four of nine), nodular induration of inner circular layer (four of nine) and grouping of outer longitudinal layer into bundles (three of nine); these were not seen in complete rectal prolapse or control specimens. CONCLUSIONS--These features, which resemble the features of high pressure sphincter tissue, may be of aetiological importance, and suggest a different pathogenesis for these two disorders. Excess collagen was seen in both disorders, was more severe in solitary rectal ulcer syndrome specimens, and probably reflects a response to repeated trauma.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Altemeier W. A., Culbertson W. R., Schowengerdt C., Hunt J. Nineteen years' experience with the one-stage perineal repair of rectal prolapse. Ann Surg. 1971 Jun;173(6):993–1006. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197106010-00018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodén B., Snellman B. Procidentia of the rectum studied with cineradiography. A contribution to the discussion of causative mechanism. Dis Colon Rectum. 1968 Sep-Oct;11(5):330–347. doi: 10.1007/BF02616986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devadhar D. S. Surgical correction of rectal procidentia. Surgery. 1967 Nov;62(5):847–852. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford M. J., Anderson J. R., Gilmour H. M., Holt S., Sircus W., Heading R. C. Clinical spectrum of "solitary ulcer" of the rectum. Gastroenterology. 1983 Jun;84(6):1533–1540. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frykman H. M., Goldberg S. M. The surgical treatment of rectal procidentia. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1969 Dec;129(6):1225–1230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackle E. J., Parks T. G. The pathogenesis and pathophysiology of rectal prolapse and solitary rectal ulcer syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol. 1986 Oct;15(4):985–1002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madigan M. R., Morson B. C. Solitary ulcer of the rectum. Gut. 1969 Nov;10(11):871–881. doi: 10.1136/gut.10.11.871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter K. R., Riddell R. H. The solitary ulcer syndrome of the rectum. Clin Gastroenterol. 1975 Sep;4(3):505–530. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Outryve M. J., Pelckmans P. A., Fierens H., Van Maercke Y. M. Transrectal ultrasound study of the pathogenesis of solitary rectal ulcer syndrome. Gut. 1993 Oct;34(10):1422–1426. doi: 10.1136/gut.34.10.1422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Womack N. R., Williams N. S., Holmfield J. H., Morrison J. F. Pressure and prolapse--the cause of solitary rectal ulceration. Gut. 1987 Oct;28(10):1228–1233. doi: 10.1136/gut.28.10.1228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]