Abstract

Ribozyme constructs derived from group II intron RmInt1 of Sinorhizobium meliloti self-splice in vitro when incubated under permissive conditions, but exon ligation is unusually inefficient when the 5′ exon is truncated close to the IBS2 intron-binding site. One plausible explanation for this observation is the presence of an alternative intron–exon pairing between an intron segment that overlaps with the EBS2 exon-binding site and a 5′ exon site located just distal of IBS2 relative to the splice junction. Strikingly, the existence of this pairing is supported by comparative sequence analysis of introns related to RmInt1.

Keywords: group II intron, ribozyme, self-splicing, intron–exon pairings

INTRODUCTION

RmInt1 is a bacterial group II intron identified in Sinorhizobium meliloti, the nitrogen-fixing symbiont of alfalfa (Medicago sativa). Unlike intron Ll.LtrA of Lactococcus lactis, which currently serves as paradigm for group II intron mobility (for review, see Lambowitz and Zimmerly 2004), the RmInt1 intron-encoded protein lacks C-terminal DNA endonuclease and DNA-binding domains (Martínez-Abarca et al. 2000; Zimmerly et al. 2001; Dai and Zimmerly 2002a; San Filippo and Lambowitz 2002; Toro 2003). RmInt1 is nevertheless an efficient mobile element that has two retrohoming pathways for mobility, with predominant use of the nascent lagging strand at DNA replication forks for priming (Martínez-Abarca et al. 2004).

Many bacterial group II introns self-splice in vitro in the absence of the intron-encoded protein when incubated under permissive conditions (Ferat and Michel 1993; Ferat et al. 1994; Matsuura et al. 1997; Granlund et al. 2001; Adamidi et al. 2003; Ferat et al. 2003; Kosaraju et al. 2005; Tourasse et al. 2005). We now report that while this is also the case for RmInt1, trimming of the 5′ exon so as to retain only the IBS1 and IBS2 intron-binding sites results in highly inefficient exon ligation. We propose that this unexpected observation could reflect the presence of a novel intron–exon interaction, which appears to be conserved in relatives of RmInt1.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Nucleotides −20 to −1 of the 5′ exon and +1 to +5 of the 3′ exon suffice to ensure efficient homing when present in the target site of intron RmInt1, while some activity is retained in the presence of the section spanning positions −15 to +5 (Jimenez-Zurdo et al. 2003) (the latter segment encompasses the three known intron-binding sites: IBS1, from −1 to −7; IBS2, from −9 to −13; and IBS3, at +1). Since long exons are a common source of inactivity of group II ribozyme constructs (see Nolte et al. 1998), we chose consequently to trim the 5′ exon down to its last 20 and 15 nucleotides (nt) (Δ20 and Δ15 constructs) in order to facilitate the investigation of in vitro reactions of the RmInt1 ribozyme.

The resulting RNA transcripts gave rise to reasonably abundant products when incubated under conditions previously shown to be permissive for several group II introns of bacterial and mitochondrial origin (not shown; see Legend to Fig. 1 ▶). Of the two constructs, Δ15 reacted best, both in terms of apparent first-order rate constant for conversion of precursor into products (0.36 h−1, as against 0.1 h−1 for Δ20) and fraction of active precursor molecules (0.34, to be compared with 0.12). However, the yield of Δ15 ligated exons was very poor, lower in fact than with Δ20, due to the accumulation of intron-3′ exon lariat forms (Fig. 1 ▶; free 3′ exon molecules were not observed, which rules out the possibility of the so-called SER [spliced exon reopening] reaction [Jarrell et al. 1988] being responsible for the scarcity of ligated exons, the concentration of which remained stable at extended reaction times).

FIGURE 1.

Uncoupling of reaction at the 5′ splice site and exon ligation in the Δ15 construct of intron RmInt1. Ordinates correspond to the ratio of molecules having completed exon ligation (molar fraction of ligated exons over all forms containing the 3′ exon) over those having reacted at the 5′ splice (molar ratio of lariat intermediate and lariat intron over all forms containing the intron). Δ20 (open circles) and Δ15 (filled circles) precursor transcripts begin with GGGAA followed by the last 20 and 15 nt, respectively, of the 5′ exon, the intron (nucleotides 611–1759, corresponding to part of ribozyme domain IV, were replaced by CTCGA), and 147 nt of the 3′ exon. Internally labelled precursor molecules (final concentration 40 nM) were incubated in 1M (NH4)2SO4, 40 mM Tris-Cl pH 7.5, 50 mM MgCl2 at 45°C. Reaction products were separated on denaturing polyacrylamide gels and tentatively identified by comparison with molecular weight markers. Their identity was subsequently confirmed by gel extraction followed by reverse transcription, RT-PCR, and 3′-end tagging (Ferat et al. 2003). Error bars correspond to three separate replicates.

Either an intrinsically low rate of reaction at the 3′ splice site or an unstable intermediate complex between the intron-3′ exon and its 5′ exon (Jacquier and Michel 1987) could cause poor coupling of exon ligation with 5′ cleavage. Since the Δ15 construct contains all three IBS sites, the latter explanation seemed unlikely, unless this particular construct supported formation of a competing interaction either within the 5′ exon or between it and the rest of the transcript. However, another possibility was that binding of the RmInt1 intron to its 5′ exon was not restricted to the EBS1–IBS1 and EBS2–IBS2 pairings common to most group II introns: An additional, yet unidentified interaction, might be present in the Δ20 construct and lacking in Δ15.

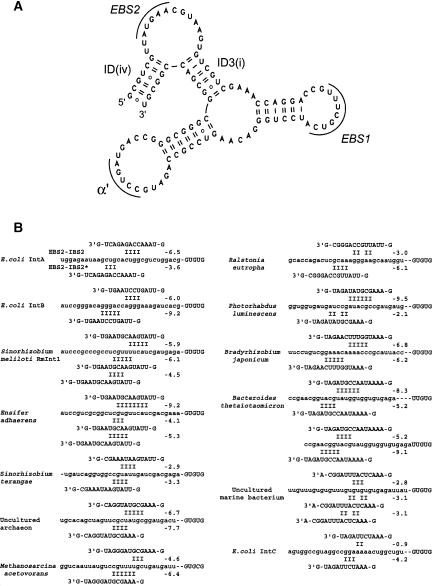

Out of the few potentially stable pairings that involve the −20 to −16 section of the 5′ exon on the one hand and segments left unpaired in the secondary structure model of the RmInt1 ribozyme on the other (Martínez-Abarca et al. 1998; Fig. 2 ▶), two happen to implicate the 14-nt EBS2-carrying segment between helices ID(iv) and ID3(i) (Fig. 2A,B ▶); compared with the conventional EBS2–IBS2 interaction, these novel pairings are generated by shifting the relative registers of the 5′ exon and internal loop by 2 and 6 nt. To our surprise, when looking at the situation in relatives of RmInt1—those belonging to subgroup IIB3 of Toro (2003), equivalent to “bacterial class D” of Zimmerly et al. (2001)—we found that the latter of those interactions (EBS2–IBS2*) was remarkably conserved in all published sequences (Fig. 2B ▶). It is especially striking that the mean estimated stability of the EBS2–IBS2* pairing (−5.3 kcal) should be very similar to that of EBS2–IBS2 (−5.9 kcal), while shifts in register relative to EBS2–IBS2 fall within a narrow range of 4–6 nt (note that the register of EBS2–IBS2 with respect to stem ID(iv) and the 5′ exon–intron boundary is itself variable, by 1 nt—exceptionally more in the Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron intron). It must also be mentioned that we were unable to come up with similar, evolutionarily conserved schemes of multiple, competing pairings of the EBS2 loop with the 5′ exon in any of the other group II intron subgroups.

FIGURE 2.

(A) A secondary structure model of the distal section of subdomain ID of the RmInt1 ribozyme. The proposed structure is slightly revised from Martínez-Abarca et al. (1998) based on comparison with other subgroup IIB3 sequences. (B) Potential for multiple pairings of the EBS2 loop with the 5′ exon in published members of the IIB3 subgroup. Exon sequences (followed by the first 5 nt of the intron) are in lowercase. For each entry, the EBS2–IBS2 pairing (defined from the near-constant relative register of the 5′ exon and EBS2 loop) is at the top and the proposed EBS2–IBS2* pairing(s) at the bottom. Alignment was on the last G of the 5′ branch of the ID(iv) helix, which is separated from the EBS2 loop by a dash (the first nucleotide of the ID3(i) helix [a G, with one exception] is also shown). Numbers are estimated free energies of base pairings at 1M NaCl and 37°C based on tables in Turner and Sugimoto (1988; pairings involving bulges were not taken into account). For the Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron intron, two possible registers of EBS2–IBS2 are shown. Published group II intron sequences that were found to be part of subgroup IIB3 (Toro 2003) with 100% bootstrap support based on phylogenetic analysis (see Ferat et al. 2003) of group II intron-encoded proteins using the PROTDIST program in PHYLIP (Phylogeny Inference Package v.3.6a2, University of Washington, Seattle) (accession numbers are followed by intron coordinates, when necessary, and reference[s]): E. coli IntA (AF512502, Dai and Zimmerly 2002b; Ferat et al. 1993); E. coli IntB (X77508, Ferat et al. 1994); Sinorhizobium meliloti RmInt1 (Y11597, Martínez-Abarca et al. 1998); Ensifer adhaerens (AY248839 and AY248840, Fernandez-Lopez et al. 2005); Sinorhizobium terangae (AY60890, Fernandez-Lopez et al. 2005); uncultured archaeon clone GZfos32G12 (AY714856, 10054–11891, Hallam et al. 2004); Methanosarcina acetivorans (NC_003552, 3708831–3706957, Galagan et al. 2002); Ralstonia eutropha (AY305378, 23468–25305, Schwartz et al. 2003); Photorhabdus luminescens (BX571862, 232816–234697, Duchaud et al. 2003); Bradyrhizobium japonicum (AF322013, 154084–155888, Gottfert et al. 2001); Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron (NC_004663, 3256655–3254752, Xu et al. 2003); uncultured marine bacterium (AY075117, Podar et al. 2002); E. coli IntC (AF512503, Ferat et al. 1993; Dai and Zimmerly 2002b).

What might be the function of an EBS2–IBS2* interaction? Except in Sinorhizobium terangae, the segments of the EBS2 loop that interact with IBS2 on the one hand and IBS2* on the other overlap, so that the two interactions must correspond to different states of the intron–exon complex. One attractive possibility suggested by the location of IBS2*, which corresponds to nucleotides believed to be bound by the DNA-unwinding activity of the Ll.LtrA protein (Zhong and Lambowitz 2003), would be that binding of IBS2* by EBS2 plays a part in the unwinding of the target of the RmInt1 intron during reverse splicing into double-stranded DNA: In the absence of a DNA-binding domain in the RmInt1 and related subgroup IIB3 intron-encoded proteins, the DNA-unwinding function would have come to be fulfilled at least in part by the ribozyme. According to this hypothesis, pairing of the first A of EBS2 with the last T of IBS2* at position −15 of the intron target site could be responsible for the latter nucleotide being critical for homing (Jimenez-Zurdo et al 2003). However, in order to explain why deleting IBS2* interferes with self-splicing, it is necessary to postulate another, additional role for the EBS2–IBS2* pairing, possibly in the conformational rearrangements that occur between transesterification at the 5′ splice site and exon ligation (Chanfreau and Jacquier 1996); displacement of IBS2 by IBS2* and a concomitant rearrangement of the EBS2 loop might facilitate the release of first-step substrates from the ribozyme catalytic center.

Of course, only an experimental approach can ultimately prove or disprove the EBS2–IBS2* interaction and indicate its function. Unfortunately, since the putative pairing overlaps with EBS2–IBS2, multiple coordinated substitutions will be required for any test. Moreover, it may be difficult to come up with an experimental setup in which disruption of individual base pairs generates measurable effects. Thus, while removal of nucleotides −20 to −16 from the RmInt1 target site results in a dramatic drop in the efficiency of homing, individual substitutions appear to be silent (Jimenez-Zurdo et al. 2003). Recall also that disruption of the EBS2–IBS2 pairing by double substitutions turned out to be essentially without effect in some exon contexts (Jacquier and Michel 1987).

Involvement of two (in fact, at most two) intron-5′ exon pairings in group II splicing and mobility has acquired the status of dogma. Any 5′ exon nucleotide that is not part of the IBS1 and IBS2 segments, yet turns out to be important for group II intron function, is currently assumed to be recognized by the intron-encoded protein (Lambowitz and Zimmerly 2004, and references therein). In this respect, our suggestion of an alternative EBS2–IBS2* pairing in RmInt1 and related introns should sound a note of warning. Irrespective of whether or not that particular pairing will prove real, the diversity of group II ribozymes is sufficient to predict that additional interactions with the 5′ exon should eventually turn up somewhere.

Article published online ahead of print. Article and publication date are at http://www.rnajournal.org/cgi/doi/10.1261/rna.2240906.

REFERENCES

- Adamidi, C., Fedorova, O., and Pyle, A.M. 2003. A group II intron inserted into a bacterial heat-shock operon shows autocatalytic activity and unusual thermostability. Biochemistry 42: 3409–3418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chanfreau, G. and Jacquier, A. 1996. An RNA conformational change between the two chemical steps of group II self-splicing. EMBO J. 15: 3466–3476. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai, L. and Zimmerly, S. 2002a. Compilation and analysis of group II intron insertions in bacterial genomes: Evidence for retroelement behavior. Nucleic Acids Res. 30: 1091–1102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ———. 2002b. The dispersal of five group II introns among natural populations of Escherichia coli. RNA 8: 1294–1307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duchaud, E., Rusniok, C., Frangeul, L., Buchrieser, C., Givaudan, A., Taourit, S., Bocs, S., Boursaux-Eude, C., Chandler, M., Charles, J.F., et al. 2003. Complete genome sequence of the entomapathogenic bacterium Photorhabdus luminescens. Nat. Biotechnol. 11: 1307–1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferat, J.L. and Michel, F. 1993. Group II self-splicing introns in bacteria. Nature 364: 358–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferat, J.L., Le Gouar, M., and Michel, F. 1994. Multiple group II self-splicing introns in mobile DNA from Escherichia coli. C. R. Acad. Sci. III 317: 141–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ———. 2003. A group II intron has invaded the genus Azotobacter and is inserted within the termination codon of the essential groEL gene. Mol. Microbiol. 49: 1407–1423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Lopez, M., Munoz-Adelantado, E., Gillis, M., Willems, A., and Toro, N. 2005. Dispersal and evolution of the Sinorhizobium meliloti group II RmInt1 intron in bacteria that interact with plants. Mol. Biol. Evol. 22: 1518–1528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galagan, J.E., Nusbaum, C., Roy, A., Endrizzi, M.G., Macdonald, P., FitzHugh, W., Calvo, S., Engels, R., Smirnov, S., Atnoor, D., et al. 2002. The Genome of M. acetivorans reveals extensive metabolic and physiological diversity. Genome Res. 12: 532–542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottfert, M., Rothlisberger, S., Kundig, C., Beck, C., Marty, R., and Hennecke, H. 2001. Potential symbiosis-specific genes uncovered by sequencing a 410-kb DNA region of the Bradyrhizobium japonicum chromosome. J. Bacteriol. 183: 1405–1412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granlund, M., Michel, F., and Norgren, M. 2001. Mutually exclusive distribution of IS1548 and GBSi1, an active group II intron identified in human isolates of group B streptococci. J. Bacteriol. 183: 2560–2569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallam, S.J., Putnam, N., Preston, C.M., Detter, J.C., Rokhsar, D., Richardson, P.M., and DeLong, E.F. 2004. Reverse methanogenesis: Testing the hypothesis with environmental genomics. Science 305: 1457–1462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacquier, A. and Michel, F. 1987. Multiple exon-binding sites in class II self-splicing introns. Cell 50: 17–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarrell, K.A., Peebles, C.L., Dietrich, R.C., Romiti, S.L., and Perlman, P.S. 1988. Group II intron self-splicing. Alternative reaction conditions yield novel products. J. Biol. Chem. 263: 3432–3439. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez-Zurdo, J.I., Garcia-Rodriguez, F.M., Barrientos-Duran, A., and Toro, N. 2003. DNA target site requirements for homing in vivo of a bacterial group II intron encoding a protein lacking the DNA endonuclease domain. J. Mol. Biol. 326: 413–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosaraju, P., Pulakat, L., and Gavini, N. 2005. Analysis of the genome of Azotobacter vinelandii revealed the presence of two genetically distinct group II introns on the chromosome. Genetica 124: 107–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambowitz, A.M. and Zimmerly, S. 2004. Mobile group II introns. Annu. Rev. Genet. 38: 1–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Abarca, F., Zekri, S., and Toro, N. 1998. Characterization and splicing in vivo of a Sinorhizobium meliloti group II intron associated with particular insertion sequences of the IS630-Tc1/IS3 retroposon superfamily. Mol. Microbiol. 28: 1295–1306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Abarca, F., Garcia-Rodriguez, F.M., and Toro, N. 2000. Homing of a bacterial group II intron with an intron-encoded protein lacking a recognizable endonuclease domain. Mol. Microbiol. 35: 1405–1412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Abarca, F., Barrientos-Duran, A., Fernandez-Lopez, M., and Toro, N. 2004. The RmInt1 group II intron has two different retrohoming pathways for mobility using predominantly the nascent lagging strand at DNA replication forks for priming. Nucleic Acids Res. 32: 2880–2888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuura, M., Saldanha, R., Ma, H., Wank, H., Yang, J., Mohr, G., Cavanagh, S., Dunny, G.M., Belfort, M., and Lambowitz, A.M. 1997. A bacterial group II intron encoding reverse transcriptase, maturase, and DNA endonuclease activities: Biochemical demonstration of maturase activity and insertion of new genetic information within the intron. Genes & Dev. 11: 2910–2924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolte, A., Chanfreau, G., and Jacquier, A. 1998. Influence of substrate structure on in vitro ribozyme activity of a group II intron. RNA 4: 694–708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podar, M., Mullineaux, L., Huang, H.R., Perlman, P.S., and Sogin, M.L. 2002. Bacterial group II introns in a deep-sea hydrothermal vent environment dagger. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68: 6392–6398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- San Filippo, J. and Lambowitz, A.M. 2002. Characterization of the C-terminal DNA-binding/DNA endonuclease region of a group II intron-encoded protein. J. Mol. Biol. 324: 933–951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, E., Henne, A., Cramm, R., Eitinger, T., Friedrich, B., and Gottschalk, G. 2003. Complete nucleotide sequence of pHG1: A Ralstonia eutropha H16 megaplasmid encoding key enzymes of H(2)-based ithoautotrophy and anaerobiosis. J. Mol. Biol. 332: 369–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toro, N. 2003. Bacteria and archaea group II introns: Additional mobile genetic elements in the environment. Environ. Microbiol. 5: 143–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tourasse, N.J., Stabell, F.B., Reiter, L., and Kolsto, A.B. 2005. Unusual group II introns in bacteria of the Bacillus cereus group. J. Bacteriol. 187: 5437–5451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner, D.H. and Sugimoto, N. 1988. RNA structure prediction. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biophys. Chem. 17:167–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J., Bjursell, M.K., Himrod, J., Deng, S., Carmichael, L.K., Chiang, H.C., Hooper, L.V., and Gordon, J.I. 2003. A genomic view of the human-Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron symbiosis. Science 299: 2074–2076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, J. and Lambowitz, A.M. 2003. Group II intron mobility using nascent strands at DNA replication forks to prime reverse transcription. EMBO J. 22: 4555–4565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerly, S., Hausner, G., and Wu, X. 2001. Phylogenetic relationships among group II intron ORFs. Nucleic Acids Res. 29: 1238–1250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]