Abstract

Cytoplasmic male sterility (CMS) and nucleus-controlled fertility restoration are widespread plant reproductive features that provide useful tools to exploit heterosis in crops. However, the molecular mechanism underlying this kind of cytoplasmic–nuclear interaction remains unclear. Here, we show in rice (Oryza sativa) with Boro II cytoplasm that an abnormal mitochondrial open reading frame, orf79, is cotranscribed with a duplicated atp6 (B-atp6) gene and encodes a cytotoxic peptide. Expression of orf79 in CMS lines and transgenic rice plants caused gametophytic male sterility. Immunoblot analysis showed that the ORF79 protein accumulates specifically in microspores. Two fertility restorer genes, Rf1a and Rf1b, were identified at the classical locus Rf-1 as members of a multigene cluster that encode pentatricopeptide repeat proteins. RF1A and RF1B are both targeted to mitochondria and can restore male fertility by blocking ORF79 production via endonucleolytic cleavage (RF1A) or degradation (RF1B) of dicistronic B-atp6/orf79 mRNA. In the presence of both restorers, RF1A was epistatic over RF1B in the mRNA processing. We have also shown that RF1A plays an additional role in promoting the editing of atp6 mRNAs, independent of its cleavage function.

INTRODUCTION

Mitochondrial genomes encode only a fraction of the genetic information required for their biogenesis and function. Consequently, a large number of genetic and biochemical features present in plant mitochondria arose in the context of coevolution and coordinated gene functions between the mitochondrial and nuclear genomes (Mackenzie and McIntosh, 1999). Cytoplasmic male sterility (CMS) is a widespread phenomenon observed in >150 flowering plant species (Laser and Lersten, 1972). CMS is a maternally inherited trait and is often associated with unusual open reading frames (ORFs) found in mitochondrial genomes, and in many instances, male fertility can be restored specifically by nuclear-encoded, fertility restorer (Rf) genes (Schnable and Wise, 1998). Therefore, CMS/Rf systems are ideal models for studying the genetic interaction and cooperative function of mitochondrial and nuclear genomes in plants.

CMS/Rf systems have long been exploited for hybrid breeding to enhance the productivity of certain crops. In rice (Oryza sativa), several CMS/Rf systems defined by the different CMS cytoplasm with distinct genetic features have been identified. These include CMS-BT (Boro II), CMS-WA (wild abortive), and CMS-HL (Honglian) (Shinjyo, 1969; Lin and Yuan, 1980; Rao, 1988). These systems have been widely used for hybrid rice breeding in China and other Asian countries as hybrid rice crops that often produce higher yields than inbred varieties (Li and Yuan, 2000; Virmani, 2003).

To date, a number of genetic loci for CMS and fertility restoration have been mapped in various plant species. Recently, Rf genes have been cloned from maize (Zea mays), petunia (Petunia hybrida), radish (Raphanus sativus), and rice (Cui et al., 1996; Bentolila et al., 2002; Brown et al., 2003; Desloire et al., 2003; Koizuka et al., 2003; Komori et al., 2004), but very few CMS candidate genes have been functionally tested, and the molecular mechanisms of the CMS/Rf systems generally remain unclear (Schnable and Wise, 1998; Wise and Pring, 2002; Hanson and Bentolila, 2004). Of the cloned Rf genes, maize Rf2 encodes an aldehyde dehydrogenase (Liu et al., 2001), and the others are members of a recently defined large gene family encoding pentatricopeptide repeat (PPR)–containing proteins (Small and Peeters, 2000). Many PPR genes are considered to encode RNA binding proteins and potentially play important roles in organelle biogenesis. So far, only a few PPR genes of various organisms have been studied in detail, and little is known about their molecular functions (Lurin et al., 2004; Schmitz-Linneweber et al., 2005).

The BT-cytoplasm of rice has been primarily identified in an indica variety (O. sativa subsp indica), Chinsurash Boro II (Shinjyo, 1969), and then transferred into a number of japonica and a few indica varieties by recurrent backcrossing. It is known that male fertility restoration in the CMS-BT/Rf system is controlled by the locus Rf-1 on chromosome 10 (Shinjyo, 1975; Yu et al., 1995; Akagi et al., 1996). The CMS-BT/Rf system is gametophytic in nature (Shinjyo, 1975) (i.e., the male-sterility phenotype appears in male gametophytes). The fertility restoration occurs only in those carrying the Rf-1 allele. The restoring allele Rf-1, also called the dominant one in some documents, is present in some indica lines, but typical japonica lines (O. sativa subsp japonica) carry only the nonrestoring allele rf-1 (Shinjyo, 1975; Zhu, 2000).

The mitochondrial genome of the BT-cytoplasm contains two duplicated copies of the atp6 gene encoding a subunit of the ATPase complex (Kadowaki et al., 1990; Iwabuchi et al., 1993). These copies, N-atp6 and B-atp6, are transcribed constitutively to produce mRNAs of different lengths due to the B-atp6 mRNA having an additional downstream sequence containing a predicted ORF called orf79 (Akagi et al., 1994, 1995). The roles that B-atp6 and orf79 play in CMS remain unclear, although it was proposed that RNA editing of B-atp6 or abnormal transcripts corresponding to the B-atp6/orf79 region may be involved (Iwabuchi et al., 1993; Akagi et al., 1994). Recently, a gene has been identified as the Rf-1 restorer (Komori et al., 2004). However, the complete nature of the chromosomal region carrying Rf-1 and the molecular mechanism underlying its fertility restoration function have not been clarified.

In this study, we demonstrate that orf79, when expressed in Escherichia coli, is toxic and that its expression in CMS lines and transgenic rice plants causes gametophytic male sterility. We cloned the genes in the Rf-1 locus and demonstrated it to be a cluster of duplicated genes of the PPR gene family. Two members of this gene cluster can restore male fertility by silencing orf79 mRNA via different mechanisms. Furthermore, we show that one of the Rf genes plays another role in RNA editing of atp6. Thus, our results demonstrate the mechanistic link between the molecular functions of the CMS and Rf genes. More generally, it also provides new insights into the molecular interaction between the mitochondrial and nuclear genomes and the function of PPR proteins.

RESULTS

The Chimeric Gene orf79 Encodes a Cytotoxic Peptide and Confers Gametophytic CMS

Since our results showed that the editing level of atp6 is not likely correlated with the male fertility status (see below), we examined the possible role of orf79 in CMS. The 5′ region of orf79 is similar to the rice mitochondrial cox1 gene encoding cytochrome oxidase subunit I, while the 3′ region is of unknown origin (Akagi et al., 1994). This gene was predicted to encode a transmembrane protein with a molecular mass of 8.9 kD (Figure 1A). To test the function of orf79, a DNA fragment of the coding sequence (fragment I, Figure 1A) was cloned in frame into the expression unit of a bacterial expression vector. It was observed that expression of this protein was lethal to the host E. coli cells, with cell lysis leading to a rapid decrease in cell density (Figures 1B and 1C). When a 15-bp segment was deleted from the 3′ end of orf79 (fragment II), cell lethality was not observed (Figures 1B and 1C) even though the protein was expressed at a high level (Figure 1D). These observations indicate that orf79 encodes a cytotoxic peptide and its C terminus is necessary for the cytotoxicity.

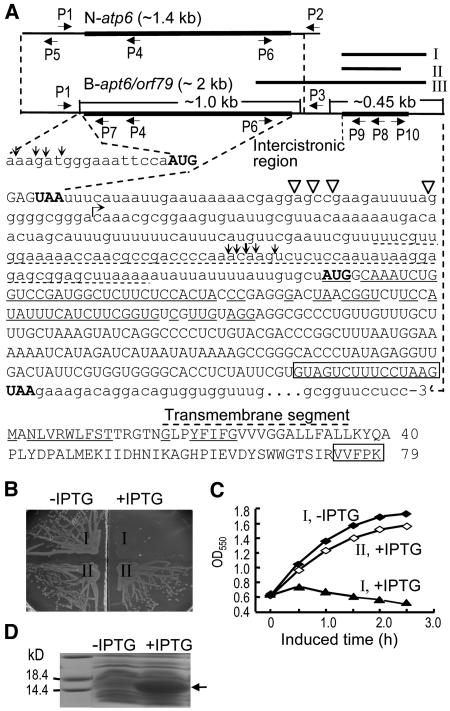

Figure 1.

Characterization of the CMS-Associated Gene in Rice with BT-Cytoplasm.

(A) The structures of N-atp6 and B-atp6/orf79 transcripts, the sequence downstream of B-atp6, and the ORF79 peptide sequence. The primers P1, P2, and P3 were used for RT-PCR to examine the editing of N-atp6 and B-atp6 mRNAs. To determine the 5′ and 3′ ends of the primary (N-atp6) and processed RNA fragments containing B-atp6 or orf79 by a CR-RT-PCR method (Kuhn and Binder, 2002) (see Figure 7B), the primers P4 and P8 were used for the reverse transcription of the circularly ligated RNAs, and the reverse-directed primer pairs P5/P6, P7/P6, and P9/P10 for the PCR. The 5′ and 3′ termini of the processed B-atp6 and orf79 RNA fragments (∼1 and 0.45 kb) are indicated by vertical arrows and open triangles, respectively. The primary 5′ and 3′ termini of N-atp6 and B-atp6/orf79 mRNAs and their different downstream sequences (starting from the bent arrow) have been described (Iwabuchi et al., 1993). The nucleotides identical to cox1 and the encoding amino acids are underlined. The dotted underline indicates a segment identical to the 5′ UTR of a predicted mitochondrial gene orf91 (Itadani et al., 1994). Rectangles indicate the deleted nucleotides in fragment II and the amino acids.

(B) and (C) Effect of orf79 expression with fragments I and II (Figure 1A), indicated by I and II, respectively, on the growth of E. coli cells on an agar plate (B) and in liquid cultures (C) with or without isopropylthio-β-d-galactoside (IPTG). In the liquid cultures (C), IPTG was added when the cell growth reached OD550 = 0.6.

(D) The expressed recombinant ORF79 protein (arrowed) with fragment II.

To test whether the expression of orf79 causes male sterility in rice, a plasmid based on the binary vector was prepared, which carries a fusion gene of the mitochondrion transit signal from an Rf gene (Rflb; see below) and the orf79 coding sequence controlled by the 35S promoter of Cauliflower mosaic virus (CaMV35S) (Figure 2A). This plasmid was transferred into a fertile rice line with normal cytoplasm. Eighteen transgenic T0 generation plants were obtained. These plants, containing single or multiple T-DNA insertions (data not shown), exhibited a semi-male-sterility phenotype wherein ∼50% or more of the pollen grains were aborted (Figures 2C and 2D). The spikelet fertility (seed setting rate) of the T0 plants ranged from 80 to 90%, indicating that female fertility was unaffected in the transgenic lines. Analysis of the T1 progeny of a T0 plant with a single T-DNA insertion showed that the transgene was present in 36 and absent in 32 plants, fitting a 1:1 segregation ratio (rather than 3:1). Furthermore, the semi-male-sterility phenotype in this population cosegregated with the presence of the transgene (Figure 2E). We determined the T-DNA insertion site in this transgenic line by thermal asymmetric interlaced PCR (Liu and Whittier, 1995) amplification and sequencing of the flanking sequences and found no gene to be tagged (data not shown). This eliminated the possibility of T-DNA insertion in a nuclear gametophytic gene.

Figure 2.

Functional Test of orf79 in Male Sterility.

(A) The binary construct for expression of recombinant orf79 in rice. P35S, the CaMV35S promoter; Rf1b-5′, the 5′ segment of Rf1b encoding mitochondrion transit signal.

(B) to (D) Pollen grains of a normal fertile rice line (B) and orf79 transgenic T0 rice plants with single (C) or two (D) T-DNA insertions. The darkly stained pollens were fertile and the lightly stained were sterile. Bars = 50 μm.

(E) Cosegregation of the orf79 transgene and the semi-male-sterility (s) in a T1 family with single T-DNA insertion as assayed by RNA gel blot analysis of young panicle RNA using orf79 as a probe. f, full male fertility.

It is expected that if the orf79 transgene was not correlated to pollen sterility, or it caused partial male sterility with a sporophytic effect based on the diploid genotype of the gene, it would segregate at a 3:1 rather than a 1:1 ratio in the progeny. These results indicate that the orf79 transgene was transmitted normally through the female germ line but poorly or not at all through pollen.

The Rf-1 Locus Comprises Two Rf Genes for the CMS-BT System

To clone Rf-1, we mapped the locus to a 37-kb region (Figure 3A) using molecular markers (see Supplemental Table 1 online) and an F2 population. A contig covering the Rf-1 locus region (Figure 3B) was constructed with clones from a genomic library of transformation-competent artificial chromosomes (TACs) (Liu et al., 1999) of the elite restorer line Minghui63 (MH63) (Liu et al., 2002), which contains functional Rf loci for the CMS-BT and CMS-WA systems. A TAC clone (M-L19) covering the 37-kb region was sequenced. In this sequence, an ORF called ORF#1 was predicted to encode a mitochondrion-targeting protein, and this prediction was confirmed using fusion to green fluorescent protein (GFP) (Figure 4A). A 7.4-kb fragment containing ORF#1 from M-L19 (Figure 3C) was transferred into a CMS-BT line to test for fertility restoration, and 21 transgenic T0 plants were obtained. Expression of the introduced candidate gene was confirmed by RT-PCR with marker 01-45 (see Supplemental Figure 5 online). Approximately 50% of pollen grains within individual flowers of the T0 plants showed restored viability (Figure 5B). The seed-setting rates in the T0 plants ranged up to ∼70% (Figure 5C), demonstrating varying degrees of fertility restoration. These results show that ORF#1 is an Rf gene for the CMS-BT system.

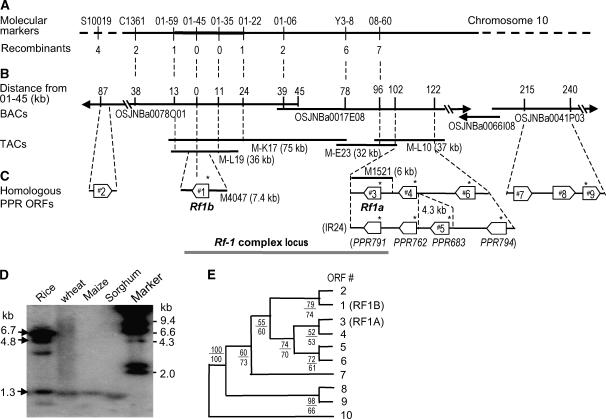

Figure 3.

Mapping and Cloning of the Rf Genes and Characterization of the PPR Subfamily.

(A) Molecular mapping of an Rf gene (Rf1b) for the Rf-1 locus using an F2 population generated from a cross between a CMS line 731A and a restorer line C9083, in which Rf1b is functional. The numbers of recombinants between the markers and Rf1b are shown.

(B) Physical maps based on BACs (Rice Chromosome 10 Sequencing Consortium, 2003) and TACs from a restorer line MH63 that contains two functional Rf genes (Rf1a and Rf1b). Rf1b was located to a 37-kb region by the molecular mapping. The pCAMBIA1300-based subclones M4047 and M1521 were able to restore the male fertility of a CMS-BT line by transformation.

(C) The PPR gene cluster consisting of Rf1a and Rf1b and their homologs. The ORFs RRR791, PPR762, and PPR794 of a restorer line IR24 (Komori et al., 2004) are allelic to ORFs #3, #4, and #6 of MH63, respectively. In the ORF#1 and #3-#6 regions, the locations of the PPR ORFs in the genome of a japonica cultivar Nipponbare are the same as MH63. ORFs with predicted or experimentally confirmed mitochondrion transit signals are marked by an asterisk.

(D) DNA gel blot analysis of HindIII-digested genomic DNA of rice (MH63) and other plant species using Rf1b as a probe. The fragments of 6.7, 4.8, and 1.3 kb correspond to fragments containing whole or parts of the ORFs #1, #6, and #3/#4 (overlapped), respectively, according to the sequence of M-L19 and M-L10.

(E) Phylogenetic analysis of the PPR protein subfamily. ORF#10 is a gene located on chromosome 8. Numbers below the branches indicate the bootstrap proportions (%) for maximum parsimony (above) and maximum likelihood (below) analyses.

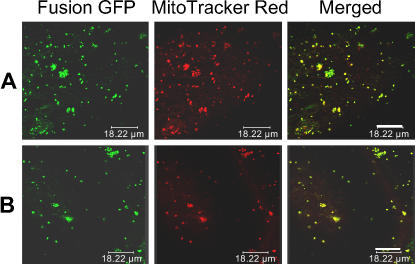

Figure 4.

Products of the Rf Genes Are Directed to Mitochondria.

Green fluorescence spots in bombarded onion epidermal cells show the expression of GFP fused with the N-terminal sequences of ORF#1 (A) or ORF#3 (B) containing putative mitochondrion transit signals. The images observed by confocal scanning microscopy show parts of single cells. The GFP fusion proteins are targeted to the mitochondria, according to the colocalization of GFP images with those stained with mitochondrion-specific dye (MitoTracker Red) in the same cells. Bars = 18 μm.

Figure 5.

Functional Complementation Test of the Rf Gene Candidates.

(A) Completely sterile pollen of a CMS-BT line KFA.

(B) Fertility-restored pollen in dark staining (∼50%) of an ORF#1 transgenic T0 plant of KFA. Bars in (A) and (B) = 50 μm.

(C) and (D) Panicles of the transgenic T0 plants with ORF#1 (Rf1b) and ORF#3 (Rf1a) transgenes, respectively, showing restored spikelet fertility.

In a parallel study to isolate another rice Rf gene for the CMS-WA system, we identified and sequenced a TAC clone, M-L10, which is located close to M-L19 (Figures 3B and 3C). Three adjacent ORFs with homology to ORF#1 were predicted in this clone (Figure 3C). These ORFs also encode proteins with predicted mitochondrion transit signals. The presence of the mitochondrion transit signal in ORF#3 was further confirmed by the GFP assay (Figure 4B). Functional complementation tests of DNA fragments from M-L10 of MH63 showed that a clone (M1521) containing ORF#3 could restore male fertility to a CMS-BT line (Figure 5D) and process the B-atp6/orf79 transcript in transgenic plants (see below), while other clones containing ORF#4 or ORF#6 could not (data not shown). Sequence analysis identified that, except for a single nucleotide variation, ORF#3 is identical to the recently reported gene PPR791/PPR8-1/Rf-1A for Rf-1 (Kazama and Toriyama, 2003; Akagi et al., 2004; Komori et al., 2004).

The fertility restorer of CMS-BT has long been described as the single locus Rf-1 (Shinjyo, 1975; Akagi et al., 1996). From our data it is evident that Rf-1 is actually a complex locus comprising at least two Rf genes within an ∼105-kb region, and either of these genes is sufficient to restore fertility to BT rice. To distinguish the two genes, we have renamed them as Rf1a for ORF#3 and Rf1b for ORF#1 (Figure 3C).

Sequence Analysis of the Rf Genes

Rf1a and Rf1b are intronless genes that encode PPR proteins of 791 amino acids (87.6 kD) and 506 amino acids (55.4 kD) (Figure 6A; see Supplemental Figures 1 to 3 online), respectively, and share 70% identity between their protein sequences. RF1A and RF1B contain mitochondrion transit signals at the N termini and contiguous arrays of 18 and 11 PPR repeats, respectively. No other known motifs were found in these proteins.

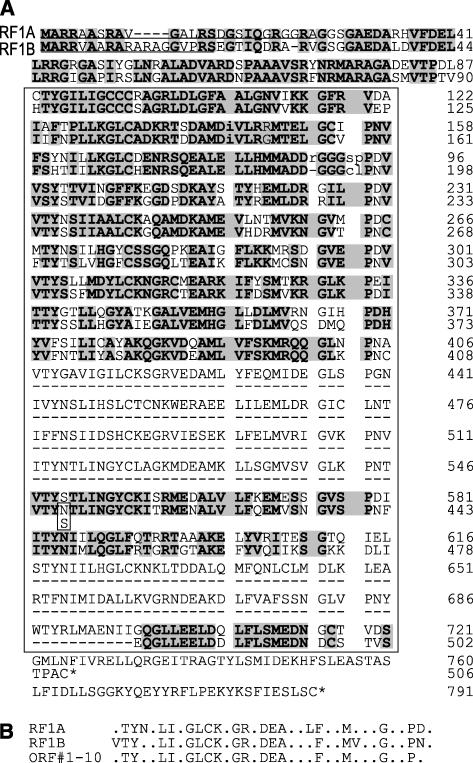

Figure 6.

The Rice Restorer Proteins and PPR Consensus Sequences of the Rice PPR Subfamily.

(A) Alignment of RF1A and RF1B sequences from MH63. The PPR repeats are inside the rectangle, of which the second and third are PPR-like L motif. The functional alteration of Asn412-to-Ser between proteins encoded by Rf1b and rf1b is shown. The underlined sequences correspond to mitochondrion transit signals predicted with probabilities of 0.95 and 0.97, respectively.

(B) PPR consensus sequences for RF1A, RF1B, and all the members of the rice PPR subfamily.

To identify functional variations between the restoring Rf1b and nonrestoring rf1b alleles, we sequenced the gene of six restorer lines and six nonrestorer (CMS or maintainer) lines. A total of nine amino acid substitutions were detected; among these, a common alteration of Asn412-to-Ser, caused by an A1235-to-G variation, was found between the Rf1b and rf1b allele groups (Table 1). This mutation could account for the loss of the restoration function. Four rf1a alleles from japonica lines were identical to each other and encode a truncated putative protein of 266 amino acids due to a frame-shift mutation, which is consistent with previous reports (Kazama and Toriyama, 2003; Komori et al., 2004). In addition, we found another rf1a allele in an indica line encoding a full-length protein with 55 substituted amino acids (see Supplemental Figure 2 online).

Table 1.

Nucleotide and Amino Acid Variations among the Rf1b and rf1b Alleles in Restorer and Nonrestorer Lines

| Nucleotide Positiona

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rice Line | Genotype | 12 | 17 | 24 | 26 | 97 | 102 | 153 | 231 | 393 | 421 | 450 | 466 | 704 | 847 | 979 | 1125 | 1203 | 1235 | 1379 |

| C9083(j)b | Rf1b | c/Rc | c/A | c/R | c/A | g/A | c/G | c/A | t/R | g/L | a/T | c/R | g/G | t/I | c/Q | g/D | c/V | g/Q | a/N | c/A |

| MH63(i)b | Rf1b | c/R | c/A | c/R | c/A | g/A | c/G | c/A | c/R | g/L | a/T | c/R | g/G | c/T | c/Q | t/Y | t/V | c/Q | a/N | g/G |

| C418(j) | Rf1b | c/R | c/A | a/R | g/G | g/A | c/G | c/A | c/R | g/L | a/T | c/R | g/G | t/I | c/Q | g/D | c/V | g/Q | a/N | c/A |

| Xiangqing(j) | Rf1b | c/R | a/D | c/R | c/A | g/A | a/G | c/A | c/R | g/L | a/T | c/R | g/G | t/I | c/Q | g/D | c/V | g/Q | a/N | c/A |

| Teqing(i) | Rf1b | t/R | c/A | c/R | c/A | g/A | a/G | t/A | c/R | g/L | a/T | c/R | g/G | c/T | c/Q | g/D | c/V | g/Q | a/N | c/A |

| C98(j) | Rf1b | c/R | c/A | c/R | c/A | g/A | c/G | c/A | c/R | g/L | a/T | c/R | g/G | t/I | c/Q | g/D | c/V | g/Q | a/N | c/A |

| 731A(j) | rf1b | c/R | c/A | c/R | c/A | g/A | a/G | c/A | c/R | g/L | a/T | t/R | a/S | t/I | c/Q | g/D | c/V | g/Q | g/S | c/A |

| KFA(j) | rf1b | c/R | c/A | c/R | c/A | g/A | a/G | t/A | c/R | t/L | g/A | t/R | a/S | c/T | c/Q | g/D | c/V | g/Q | g/S | c/A |

| ZD88A(j) | rf1b | c/R | c/A | c/R | c/A | g/A | a/G | t/A | c/R | g/L | a/T | t/R | a/S | t/I | c/Q | g/D | c/V | g/Q | g/S | c/A |

| WYJ8A(j) | rf1b | c/R | c/A | c/R | c/A | t/F | a/G | c/A | c/R | g/L | a/T | c/R | g/G | t/I | a/K | g/D | c/V | g/Q | g/S | c/A |

| Nipponbare(j) | rf1b | c/R | c/A | c/R | c/A | g/A | c/G | c/A | c/R | g/L | a/T | t/R | a/S | t/I | c/Q | g/D | c/V | g/Q | g/S | c/A |

| Fuyu1A(i) | rf1b | c/R | c/A | c/R | c/A | g/A | c/G | c/A | c/R | t/L | a/T | c/R | g/G | c/T | c/Q | t/Y | t/V | g/Q | g/S | c/A |

Nucleotide positions in the coding regions are shown.

(j) and (i) indicate the nuclear backgrounds of japonica and indica, respectively. The restorer lines with japonica nuclear background (j) are restorer near-isogenic lines bred by recurrent backcrosses with indica restorer lines as the donor parents.

Nucleotide/amino acid.

A PPR Subfamily Involving the Rf Genes

Genomic DNA gel blot analysis using Rf1b as a probe detected several fragments of different signal intensities in rice and one weak hybridizing signal in wheat (Triticum aestivum), maize, and sorghum (Sorghum bicolor) (Figure 3D). No hybridization signal was detected in several dicotyledon plants (Arabidopsis thaliana, radish, and Brassica; data not shown). The sequence homology between the rice restorer proteins and those from petunia and radish (Bentolila et al., 2002; Brown et al., 2003; Desloire et al., 2003; Koizuka et al., 2003) are low (<30%). Through database searching, seven or eight homologs of Rf1a and Rf1b were found in the genomes of different rice varieties. These homologs share 61 to 93% amino acid identity and a PPR consensus sequence (Figure 6B), thus forming a rice-specific PPR gene subfamily. Apart from ORF#10 on chromosome 8, all homologs are clustered within an ∼330-kb region on chromosome 10 (Figure 3C). The genome of restorer line IR24 contains an additional homolog PPR683 (Komori et al., 2004) located adjacent to Rf1a, suggesting a recent duplication event. With one exception (ORF#2), these putative PPR proteins contain two long PPR motifs (Figure 6A; see Supplemental Figure 4 online), which have also been identified in proposed PPR proteins of land plants (Lurin et al., 2004). Phylogenetic analysis showed that the homology relationship between these members is consistent with their chromosomal locations, with those grouped into the same or closely related clades more tightly linked (Figure 3E).

RF1A and RF1B Mediate Destruction of B-atp6/orf79 mRNA with Different Mechanisms

RT-PCR analysis showed that the Rf genes were expressed in all organs tested, including young panicles, leaves, and roots (see Supplemental Figure 5 online). However, RNA gel blot hybridizations detected no signal, even on rice poly(A)+ mRNA samples (see Supplemental Figure 5 online), indicating a low level of constitutive expression.

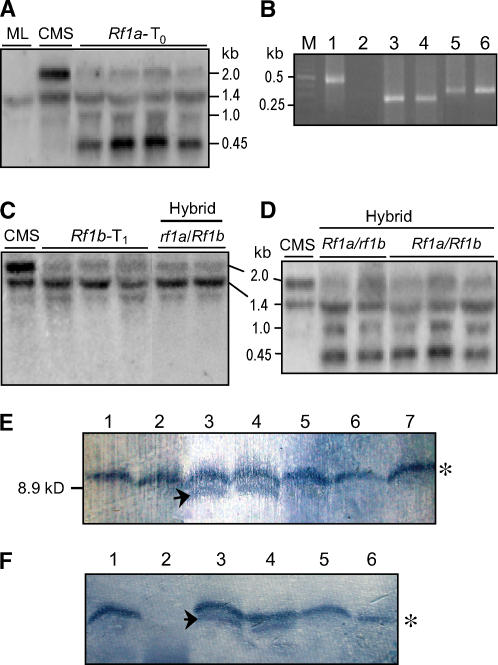

To gain insights into the molecular mechanism of the CMS restoration interaction, we analyzed the mRNA levels of B-atp6/orf79 in the presence of Rf1a and/or Rf1b. In Rf1a transgenic plants, the steady state level of B-atp6/orf79 mRNA was greatly reduced, while two new transcripts of ∼1 and 0.45 kb were detected (Figure 7A) when fragment III (see Figure 1A) was used as a probe. This altered expression profile is similar but not identical to the previous observations in cytoplasmic hybrid plants (Iwabuchi et al., 1993; Akagi et al., 1994). Two possible mechanisms by which RF1A affects the transcript profile are posttranscriptional processing or alterative de novo transcription. To address this issue, we characterized the 5′ and 3′ termini of the altered transcripts using a circularized RNA (CR)-RT-PCR method (Kuhn and Binder, 2002). With this method, the 5′ termini of cleavage-processed RNA molecules can be ligated to their 3′ ends for inverse RT-PCR, whereas 5′ termini of primary transcripts carrying triphosphates must be treated with tobacco acid pyrophosphatase (TAP) to remove the 5′ pyrophosphate to allow ligation to occur (Kuhn et al., 2005).

Figure 7.

Processing of B-atp6/orf79 mRNA and Suppression of the ORF79 Production by the Rf Genes.

(A) Transcript profile of B-atp6/orf79 in transgenic plants with Rf1a assayed by RNA gel blot analysis. The relatively low signal intensity of the 1.4- and 1.0-kb bands was due to the relatively smaller portion of the DNA fragment III probe (see Figure 1A) hybridizing to atp6. The 1.4-kb band (N-atp6) also served as a loading control. ML, maintainer line.

(B) CR-RT-PCR analysis of the 5′ and 3′ termini of the primary N-atp6 transcript from a maintainer line (lanes 1 and 2), the processed B-atp6 (lanes 3 and 4), and orf79 (lanes 5 and 6) mRNA fragments from an Rf1a transgenic plant using the primer pairs P5/P6, P7/P6, and P9/P10, respectively (see Figure 1A). The RNA samples were treated with (lanes 1, 3, and 5) and without (lanes 2, 4, and 6) TAP before the RNA ligation reaction. M, molecular weight marker.

(C) Transcript profile of B-atp6/orf79 in transgenic and fertility-restored hybrid plants with Rf1b.

(D) Transcript profile of B-atp6/orf79 in fertility-restored hybrid plants with Rf1a alone or both of Rf1a and Rf1b.

(E) Immunoblot analysis probed with an antibody to ORF79. Proteins were prepared from anthers containing microspores of a CMS-BT line (lanes 3 and 4), fertility-restored transgenic plants with Rf1a (lane 1) or Rf1b (lane 2), fertility-restored hybrid plants carrying Rf1a and Rf1b (lanes 5 and 6), and a maintainer line (lane 7). The specific band (lanes 3 and 4) for ORF79 is indicated with an arrow, and the top one marked with an asterisk is a cross-reacting unknown protein.

(F) Immunoblot analysis of ORF79 using proteins prepared from microspores of fertility-restored transgenic plants with Rf1a (lane 1), mitochondria of seedling leaves of the CMS-BT line (lane 2), microspores of the CMS-BT line (lanes 3 and 4), and anther wall tissue not including the microspores (lanes 5 and 6). The cross-reacting unknown protein, as well as ORF79, was not detected in the mitochondria of the seedling leaves of the CMS-BT line (lane 2).

The results showed that, without the TAP treatment, CR-RT-PCR products could only be obtained from the newly generated transcripts containing a B-atp6 or orf79 region in an Rf1a transgenic plant (Figure 7B). Sequence analysis found that the ∼1-kb RNA molecules contained different 5′ termini located 11 to 16 bases upstream of the start codon of B-atp6 and different 3′ ends at the region just downstream of the stop codon, while the 0.45-kb orf79-containing RNAs had different 5′ termini in the intercistronic region (Figure 1A). Moreover, the feature of the multiple 5′ termini at adjacent sites of these RNAs is obviously distinct from that of primary mitochondrial mRNAs generated from different transcription initiation sites by multiple promoters, which are characterized by their scattered distribution along a certain chromosomal region (Nakazono et al., 1996; Lupold et al., 1999; Q. Zhang and Y.-G. Liu, unpublished data). Taken together, it is evident that RF1A functioned to mediate endonucleolytic cleavage of B-atp6/orf79 mRNA at three major regions, each with multiple cleaving sites. Analysis of the termini of N-atp6 transcripts from CMS-BT and Rf1a-restored plants found no cleavage processing of the molecules.

In Rf1b transgenic plants and fertility-restored hybrid plants carrying Rf1b but lacking Rf1a allele, the abundance of the B-atp6/orf79 transcript was greatly decreased, but no processed intermediate product was detected (Figure 7C). The N-atp6 transcript level was not affected by Rf1b (Figure 7C), although both atp6 copies shared identical promoter/regulatory sequences. Therefore, the reduction of the transcript could be attributed to posttranscriptional degradation mediated specifically by RF1B. The processing patterns of the mRNA by the two Rf genes in other tissues, such as leaves and Rf gene transgenic calli, were consistent with those of young panicles as described earlier (data not shown).

RF1A Is Epistatic to RF1B in mRNA Processing

Since Rf1a and Rf1b alleles, when existing alone, function independently to process the same mRNA with different mechanisms, it would be of interest to know how the mRNA is processed in the presence of both restoring alleles of the genes. It was observed that in hybrid plants carrying Rf1a and Rf1b, the pattern and abundance of the processed B-atp6/orf79 mRNA were the same as that of Rf1a alone (Figure 7D). This indicates that B-atp6/orf79 was normally transcribed and the mRNA was preferentially cleaved by the action of RF1A, exhibiting an epistatic effect over RF1B. This observation also supports the conclusion that RF1B functions to mediate the degradation of B-atp6/orf79 mRNA rather than to suppress its transcription. The mRNA fragments cleaved by RF1A were resistant to this specific degradation.

ORF79 Accumulates Specifically in the Microspores and Its Production Is Suppressed by the Rf Genes

An immunoblot was performed to examine ORF79 in the CMS-BT line and the inhibitory effect of the Rf genes on its production. The results showed that the ORF79 protein was detected in anthers, including microspores of a CMS-BT line; however, this protein was undetectable or the level greatly reduced in fertility-restored transgenic and hybrid plants with Rf1a and/or Rf1b (Figure 7E). We further performed the immunoblot analysis using proteins prepared from isolated microspores, anther wall tissue in which microspores were removed, and mitochondria purified from young seedling leaves. We found that ORF79 was detected in microspores of the CMS-BT line but not in the anther wall tissue and seedling leaves (Figure 7F). These data indicate that expression and silencing of orf79 at the protein level are correlated with CMS and restoration, respectively. Moreover, specific accumulation of the product in microspores is consistent with the genetic feature of this CMS/Rf system.

Rf1a Plays a Role to Promote atp6 mRNA Editing

We found that the restoring alleles of Rf1a and Rf1b exist widely in indica cultivars and wild rice species, regardless of the presence or absence of orf79 (X. Li and Y.-G. Liu, unpublished data). This raised a question of whether the Rf genes have other important biological functions in addition to their role as fertility restorers. To address this issue, we investigated their possible role in editing of atp6 mRNAs.

Sequence analysis of atp6 cDNA from young panicles showed that C-to-U editing occurred at 17 sites of the atp6 transcripts (see Supplemental Table 2 online). The editing sites were the same for N-atp6 and B-atp6 transcripts, indicating that the different 3′ downstream sequences did not affect the specificity of the editing sites. The editing rates of the sites in B-atp6 and N-atp6 mRNAs were relatively low and similar among plants lacking Rf1a, namely, CMS-BT lines, maintainer lines, and the Rf1b transgenic plants, irrespective of the male fertility status (Table 2; see Supplemental Table 2 online). When Rf1a was introduced by either transformation or crossing, the editing levels of both N-atp6 and the trace of uncleaved B-atp6 RNA molecules were increased significantly by 8 to 19% on average for the sites, with much higher increases seen for site 13 (Table 2). These results demonstrate that RF1A functions to promote the editing of atp6 mRNA, while Rf1b has no such effect. This activity is independent of its cleavage of B-atp6/orf79. No RNA editing was detected in the orf79 region.

Table 2.

Editing Rates (%) of Site 13 and the Average of the 17 Sites in N-atp6 and B-atp6 mRNAs in Plants with or without Rf1a or Rf1b

| N-atp6

|

B-atp6a

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Site | MLb | CMSb | Hybc | Rf1a-T1b | Rf1b-T2b | CMS | Hybc | Rf1a-T1b | Rf1b-T2b |

| 13 | 48.5 | 44.4 | 82.3 | 90.3 | 43.3 | 43.6 | 65.2 | 69.7 | 45.2 |

| Average | 83.4 | 80.2 | 97.8 | 91.2 | 81.1 | 71.5 | 89.1 | 90.5 | 76.0 |

| Duncan's testd | C | C | A | B | C | B' | A' | A' | B' |

B-atp6 cDNAs of hybrid, Rf1a-T1, and Rf1b-T2 were generated from the trace of uncleaved or undegraded B-atp6/orf79 RNA molecules.

The maintainer lines (KFB) and CMS-BT (KFA) and the fertility-restored transgenic plants (Rf1a-T1 and Rf1b-T2) have the same nuclear background.

The hybrid (Hyb) plant carried Rf1a.

The statistical analysis was performed for the 17 sites in N-atp6 or B-atp6 of the lines (see Supplemental Table 2 for details) at the 5% level. The averages marked with the same letter are not significantly different.

DISCUSSION

Abnormal Mitochondrial ORFs and CMS

CMS has been found to be associated with abnormal mitochondrial ORFs in a number of plant species (Schnable and Wise, 1998). In this study, we demonstrated that the chimeric rice gene orf79 encodes a transmenbrane protein that is cytotoxic to E. coli and that its recombinant transgene leads to gametophytic male sterility, mimicking the genetic effect of the BT-cytoplasm. This feature is distinct from that of the common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) CMS gene orf239, which results in sporophytic male sterility in transgenic tobacco plants (He et al., 1996). It was previously shown that the maize CMS-T gene urf13 also encodes a cytotoxic peptide (Dewey et al., 1988). In addition, the expression of CMS-associated genes orf552 from sunflower (Helianthus annuus) and orf138 from radish were also lethal to E. coli (Nakai et al., 1995; Duroc et al., 2005; Y.-G. Liu, unpublished data). Therefore, we suggest that many abnormal mitochondrial CMS genes, if not all, may encode cytotoxic proteins that can disrupt the development of male sporophytic and/or gametophytic cells.

The C-terminal sequence of ORF79 is similar to the predicted protein of a CMS candidate locus orf107 in sorghum (Tang et al., 1996), thus providing an unusual case of sequence similarity between CMS-associated loci in different species. Moreover, we have shown that the C-terminal region of ORF79 is essential for its cytotoxic effect in E. coli. These findings strongly suggest that the C-terminal region of the peptide is important for its detrimental effect on male development. Despite the constitutive RNA expression of orf79, its product accumulates specifically in the microspores. This provides a tight correlation between the expression of orf79 and the phenotype of gametophytic male sterility. We propose that there could be a regulatory mechanism, likely at the posttranslational level, for the specific suppression of ORF79 accumulation in the sporophytic tissues, thus restricting its detrimental effect to microspores. Further study into the mechanism behind this cell type–specific protein accumulation/degradation will provide insight into the molecular basis of gametophytic CMS in plants.

Two Distinct RNA Silencing Pathways Are Integrated in the CMS-BT/Rf System

CMS/Rf systems with two major Rf loci have been identified genetically in several plants (Schnable and Wise, 1998), including the CMS-WA (Zhang et al., 1997, 2002) and CMS-HL (Liu et al., 2004) systems in rice. This study revealed that the classical Rf-1 locus consists of two closely linked Rf genes, Rf1a and Rf1b, as members of the PPR cluster. Different restorer lines for this system may carry distinct genotypes of the two genes, with both or either being functional for restoration. Therefore, the use of different restorer lines for fine mapping has resulted in the precise location of Rf-1 to PPR791/Rf-1A (Rf1a) in previous reports (Akagi et al., 2004; Komori et al., 2004) and Rf1b in this study.

To date, only one other rice PPR gene (OsPPR1) has been the subject of functional analysis (Gothandam et al., 2005). Here, we have shown that RF1A is the key factor for the cleavage processing of B-atp6/orf79 mRNA. Despite the fact that two of the three major cleaving positions are located in a region of the B-atp6 sequence that is identical with N-atp6, this RF1A-dependent cleavage does not occur in N-atp6 mRNA. This indicates that a specific interaction between RF1A or an RF1A-containing complex and the special intercistronic/orf79 sequence is required for the cleavage activity. It is known that special sequences, other than Shine-Dalgarno–like sites, in 5′ untranslated regions (UTRs) of yeast mitochondrial mRNAs are essential for initiation of translation (Dunstan et al., 1997). Little is known about the translation machinery for plant mitochondrial mRNAs, particularly polycistronic mRNA (Giege and Brennicke, 2001). However, it is noteworthy that a 67-base segment in the intercistronic region covering one of the RF1A-dependent cleaving positions is identical to the 5′ UTR sequence of a predicted rice mitochondrial gene orf91 (Itadani et al., 1994) (Figure 1A). This sequence may play an important role in the translation initiation; thus, the destruction of this sequence by RF1A would lead to the orf79-containing mRNA fragments being untranslatable. Indeed, the production of ORF79 is blocked by the cleavage processing, as well as the degradation, of B-atp6/orf79 mRNA. Since the cleaved B-atp6 mRNA loses the entire 5′ UTR sequence, it should also be defective for translation. These facts indicate that this duplicated gene is not essential for the biological function of ATP6. However, this gene copy plays a role in the expression of orf79 through cotranscription and in the processing of the dicistronic mRNA; therefore, it is also an essential component of the CMS-BT/Rf system.

In the absence of RF1A, RF1B can function in the processing of target mRNA. However, when both are present, RF1A seems to interact preferentially with the mRNA, thus exhibiting an epistatic effect over RF1B. The inability of RF1B to destabilize the cleaved RNA fragments suggests that this cleavage also destroys a recognition sequence in the intercistronic region necessary for RF1B-dependent RNA degradation. This form of mitochondial mRNA decay pathway seems to differ from those involving processing signals of homopolymeric tails or secondary structures at the 3′ UTRs (Bellaoui et al., 1997; Dombrowski et al., 1997; Gagliardi and Leaver, 1999; Kuhn et al., 2001).

Although some Rf loci are known to affect the transcript profile of CMS-associated loci in several plant species, the action mode of these Rf loci and how the altered expressions lead to fertility restoration have not been elucidated (Hanson and Bentolila, 2004). In this regard, two major possibilities exist: the Rf genes function to suppress the expression of CMS genes that are detrimental to male development, or they compensate or normalize the impaired expression of mitochondrial genes essential for male fertility. This study demonstrated that Rf1a and Rf1b function independently to restore male fertility by silencing the CMS gene via different RNA processing pathways. Thus, there are at least two posttranscriptional controlling mechanisms for the CMS-BT/Rf system. Similar mechanisms may exist for other CMS/Rf systems with two major Rf loci, such as the rice CMS-HL and maize CMS-S (Wen et al., 2003) systems.

Functions of PPR Proteins in Organelle Biogenesis

The precise mechanism underlying how PPR proteins interact with target mRNAs remains unclear (Lurin et al., 2004). Since RF1A and RF1B lack obvious domains likely to have catalytic activity, the PPR protein–mediated RNA processing may require the activities of other cofactor(s), as proposed for the general action mode of PPR proteins (Lurin et al., 2004). The mechanism by which the Asn412-to-Ser substitution in RF1B results in a loss of the mRNA processing function is unclear. However, computer analysis detected variations in the secondary structure between the restoring and nonrestoring proteins (data not shown), which may affect the activity of the RNA–protein interaction.

Since the atp6 transcripts are edited at basal levels by unknown factors in male sterile and fertile rice plants without Rf1a, the role RF1A plays in enhancement of the atp6 editing, which is independent of the cleavage processing, appears to be redundant for the biological function of ATP6 and is not necessary for the fertility restoration. It has been reported recently that a PPR protein, CRR4, is required for editing of the chloroplast ndhD mRNA in Arabidopsis (Kotera et al., 2005). These facts suggest that some PPR proteins are involved in the editing of specific mRNAs, either as essential factors such as CRR4, or as helper factors like RF1A. Therefore, this role of RF1A is likely to be its normal function, while the activity for fertility restoration might be a new function of the gene. Similar mechanisms likely exist in other CMS/Rf systems, since in many instances the sequences of atp or other mitochondrial genes are also linked to and are cotranscribed with CMS-associated loci (Schnable and Wise, 1998).

The PPR Subfamily and the Evolutionary Relationships among CMS/Rf Systems in Rice

In rice, >600 PPR genes are predicted (Lurin et al., 2004). Many PPR genes in rice are clustered in chromosomal regions (D. Zou and Y.-G. Liu, unpublished data). It is known that PPR-containing Rf genes in petunia, radish, and rice are also clustered with their homologs (Bentolila et al., 2002; Desloire et al., 2003; Komori et al., 2004). In this study, we further characterized the unique PPR cluster involving the Rf genes in rice. Interestingly, we found that the phylogenetic relationship of members in this PPR cluster is consistent with their chromosomal locations. This and other features, such as varied numbers of members in different varieties and the existence of null alleles, provide a striking example of the rapid and dynamic evolution of multigene clusters through gene amplification, functional divergence, and birth-and-death process (Nei et al., 1997). By contrast, the homologs of these rice PPR genes in wheat, maize, and sorghum retain a single copy.

We have mapped an Rf gene for the CMS-WA system on a region corresponding to this PPR cluster (Zhang et al., 2002). In addition, by comparing the molecular maps of Rf5 and Rf6(t) for the CMS-HL system (Liu et al., 2004) with our current one, we estimated that these Rf loci may also be located in this PPR cluster region. The data suggest that a number of the members of this PPR cluster have been recruited as fertility restorers with diverged molecular functions for the same or different CMS systems. These genetic similarities demonstrate the common origin and coevolution of these systems in rice.

METHODS

Expression of orf79 in Escherichia coli and Rice

The mitochondrial DNA fragments I and II containing orf79 (Figure 1A) were amplified from the CMS-BT line KFA using the following oligonucleotide primer pairs: 5′-ATTTTUCTCGAGUCTATGGCAAATCTGGTC-3′ and 5′-GTATGTCTAGACCACCACTGTCC-3′, and 5′-ATTTTUCTCGAGUCTATGGCAAATCTGGTC-3′ and 5′-TGTCTTCTAGACTTAACGAATAGAGGAGCCCCA-3′. XhoI and XbaI sites in the primer sequences are underlined, and the corresponding enzymes were used to clone these fragments in frame into the bacterial expression vector pThioHis (Invitrogen). Expression of orf79 in E. coli TOP10F' cells was induced by adding 1 mM IPTG.

The 5′ sequences of Rf1b (Rf1b-5′, 305 bp), encoding the putative mitochondrion transit signal peptide, and the orf79 fragment were amplified using the following oligonucleotide primer pairs: 5′-CAGGCCGGTCCATGGTCACGCC-3′ and 5′-GCCCGCATCTGCAGTCAGCAG-3′, and 5′-ATTTTATCTGCAGTTATGGCAAATCTGGTC-3′ and 5′-GTATCACGTGGGATCCACCACTGTCC-3′. NcoI, PstI. and PmlI sites in the primer sequences are underlined. The fragments were each cloned with a TA-cloning vector (pMD18-T, Takara) and then linked in frame using the PstI site. A plant expression construct was prepared by replacing the NcoI-PmlI fragment (GUSPlus) in the binary vector pCAMBIA1305.1 with the fusion gene Rf1b-5′:orf79 (Figure 2A). After checking the fusion gene by sequencing, the construct was transferred into a japonica variety with normal cytoplasm by Agrobacterium tumefaciens–mediated transformation (Hiei et al., 1994).

Cloning of Rf Genes

An F2 population of 1250 plants was generated from a cross between a CMS line 731A and a restorer line C9083. The F2 plants producing full-fertile pollen grains (602 plants) and semifertile (∼50%) pollen grains (648 plants) represented plants homozygous and heterozygous for Rf-1, respectively. A total of 603 F2 plants were used for mapping. The restorer locus was mapped using three restriction fragment length polymorphism markers, Y3-8 (Zhang et al., 2002), C1361, and S10019 (MAFF DNA Bank of Japan), and five newly developed markers (see Supplemental Table 1 online). A TAC genomic library of MH63 was screened using the markers O01-35 and 08-59 as probes. For the functional complementation test, the TAC clones M-L19 and M-L10 were partially digested with Sau3AI, and DNA fragments of 5 to 8 kb were recovered and subcloned into the BamHI site of the binary vector pCAMBIA1300. Constructs containing the restorer candidates were selected and transferred into the CMS line KFA by Agrobacterium-mediated transformation (Hiei et al., 1994). Male fertility was assayed by potassium iodide (1% I2-KI) staining of pollen and the ability for seed setting after self-pollination. To select hybrid plants that carried either Rf1a or Rf1b allele generated from recombination events, a cross between the CMS line KFA and a restorer line C98 (Rf1aRf1a/Rf1bRf1b) was prepared, and the >3000 F2 plants were genotyped with the polymorphic markers 08-60 and 01-45 (Figure 3; see Supplemental Table 1 online). The sequences of the genes of the selected plants were further confirmed by sequencing. The single nucleotide polymorphic marker 01-45 located within Rf1b was designed from the A1235-to-G functional mutation, and the detection of this marker was done as follows. A primary PCR (32 cycles) using oligonucleotide primers 45F (5′-CTTCATGGGTATGCTATCG-3′) and 45R (5′-CAGTCGAAGCTTCAACGG-3′) was performed and then the product (0.5 μL) was subjected to two secondary PCRs (10 cycles) using primer pairs 45A (5′-CCTAATTGTGTTACGTATAA-3′, Rf1b-specific) and 45R, and 45G (5′-CCTAATTGTGTTACGTATAG-3′, rf1b-specific) and 45R, respectively.

Subcellular Localization

The 5′ sequences of Rf1a (222 bp) and Rf1b (231 bp) encoding the putative mitochondial targeting signals were amplified from the cloned genes using the oligonucleotide primers 5′-AGGGTCGACATGGCACGCCGCGTCG-3′ and 5′-GTGCCATGGGGTTGAAGCGGGAC-3′. After digestion with SalI and NcoI (underlined in primer sequences), the fragments were fused to and cloned in frame with the GFP coding sequence (Cormack et al., 1996) in a pUC18-based vector and placed under the control of the CaMV35S promoter. The constructs were transiently transformed into onion epidermal cells (Scott et al., 1999) on agar plates by a helium-driven accelerator (PDS/1000; Bio-Rad). Bombardment parameters were as follows: 1100 p.s.i. bombardment pressure, 1.0-μm gold particles, a distance of 9 cm from macrocarrier to the samples, and a decompression vacuum of 88,000 Pa. After culture for 1 d, the bombarded epidermal cells were treated with 500 nm of the mitochondrion-selective dye MitoTracker Red CM-H2XRos (Molecular Probes). GFP expression in general and colocalization of GFP fusion proteins to mitochondria were viewed using a confocal scanning microscope system (TCS SP2; Leica) with 488-nm laser light for fluorescence excitation of GFP and 578-nm laser light for excitation of MitoTracker Red.

RT-PCR and RNA Gel Blot Analysis

Total RNA was extracted from rice (Oryza sativa) tissue using TRIZOL reagent (Invitrogen), and poly(A)+ RNA was purified using the PolyATract kit (Promega). DNA fragment III (Figure 1A) was PCR amplified from a CMS-BT line using the following primers: 5′-GGCCGGTCATAGTTCAGT-3′and 5′-GTATGTCTAGACCACCACTGTCC-3′. The PCR product was labeled with P32-dCTP using a random-primed kit for RNA gel blot analysis. The 5′ and 3′ mRNA termini of N-atp6 and RF1A-processed atp6 and orf79 mRNA were determined by the CR-RT-PCR method (Kuhn and Binder, 2002). The oligonucleotide primers P4 (5′-TATTGAAACGGATACGCT-3′) and P8 (5′-CTCCTACAACGACACCGT-3′) were used for the initial reverse transcription of the circularly ligated B-atp6- and orf79-containing RNAs, and primer pairs P7 (5′-CTGTTCAACGAGTTCACGT-3′) and P6 (5′-ACCGGTCTGGAATTAGGTG-3′), and P9 (5′-TGGAAGACCGTTAGTCCCT-3′) and P10 (5′-CCTCTGTACGACCCGGCTT-3′) were used in inverse PCR, respectively. The 5′ and 3′ termini of the primary atp6 mRNAs were determined by the same CR-RT-PCR method with primer P4 for reverse transcription and primers P5 (5′-GACTGATCTCAACTGGCCT-3′) and P6 (5′-ACCGGTCTGGAATTAGGTG-3′) for inverse PCR, except that the RNA samples were treated with TAP (Epicentre Technologies) before RNA ligation (Kuhn et al., 2005). To investigate the editing frequencies of atp6, cDNA sequences were obtained from N-atp6 and B-atp6 transcripts from young panicles by RT-PCR using primer pairs P1 (5′-TCTCCCTTTCTAGGAGCAGAG-3′) and P2 (5′-TATGTCGCTTAGACTTGACC-3′), and P1 (5′-TCTCCCTTTCTAGGAGCAGAG-3′) and P3 (5′-TAACGCAATACACTTCCGCG-3′), respectively. The amplified cDNAs were cloned, and 40 to 60 clones for each sample were sequenced. Statistical analysis of the editing rates of the samples was performed by analysis of variance and Duncan's multiple range test using the SAS program.

Immunoblot Analysis

A peptide antigen corresponding to residues 1 to 30 of ORF79 was synthesized and used to immunize rabbits. Total proteins were extracted from various rice tissues, including anthers, isolated microspores, anther wall tissue in which the microspores were removed, and purified mitochondria from young seedling leaves. The anther wall tissue and microspores were isolated as described earlier (Honys and Twell, 2003; Sze et al., 2004), and their purities were checked by light microscopy. The proteins were separated by 20 to 25% SDS-PAGE containing 36% urea and blotted on Immobilon-PSQ transfer membrane (PVDF type; Millipore). The membrane blots were incubated in blocking buffer (1% BSA, 0.05% Tween 20, 20 mM Tris-HCl, and 500 mM NaCl, pH 7.5) for 1 h, washed twice (5 min each) with TBST (0.05% Tween 20, 20 mM Tris-HCl, and 500 mM NaCl, pH 7.5), and incubated with the primary antibody serum (1:100 dilution) for 1 h at room temperature. After two rinses (5 min each) with TBST, the blots were incubated in the secondary antibody solution (affinity-purified antibody phosphatase-labeled goat anti-rabbit IgG [H+L], 1:1000 dilution; Kirkegaard and Perry Laboratories) for 45 min at room temperature, washed twice (5 min each) with TBST, and immediately incubated in the substrate buffer (0.33 mg/mL nitroblue tetrazolium [Sigma-Aldrich], 0.165 mg/mL BCIP [Bio-Basic], 0.1 M Tris, 0.1 M NaCl, and 5 mM MgCl2, pH 9.5) for 2 min, and then the signal was detected.

Sequence Analysis

The ORF79 sequence was analyzed by the software TMHMM server v.2.0 (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/TMHMM). Gene sequences were analyzed by BLAST (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/). ORF annotation and PPR motif prediction were performed with the RiceGAAS system (http://rgp.dna.affrc.go.jp). The mitochondrion transit peptide was predicted by MITOPROT (http://mips.gsf.de/cgi-bin/proj/medgen/mitofilter/). Protein sequences were aligned using the ClustalX program (Thompson et al., 1997). We manually inspected and modified the alignment output. Phylogenetic analysis was performed with maximum parsimony and maximum likelihood methods (Ln likelihood = −3474.83) implemented in PHYLIP 3.57 (Felsenstein, 1997) and PUZZLE (γ-corrected JTT model) (Strimmer and von Haeseler, 1996). Bootstrap analysis was performed with 1000 replicates.

Accession Numbers

Sequence data from this article can be found in the GenBank/EMBL data libraries under accession numbers DQ311052 to DQ311054.

Supplemental Data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Figure 1. Genomic Sequence Comprising Rf1a and the Deduced Amino Acids.

Supplemental Figure 2. Nucleotide Sequence of an indica rf1a Allele and the Deduced Amino Acids.

Supplemental Figure 3. Genomic Sequence Comprising Rf1b and the Deduced Amino Acids.

Supplemental Figure 4. Multialignment of the Deduced Amino Acid Sequences of the PPR Subfamily Members in Rice.

Supplemental Figure 5. Expression of the Rf Alleles in Rice.

Supplemental Table 1. Molecular Markers Developed in This Study for the Mapping.

Supplemental Table 2. Editing Rates (%) of 17 Sites in N-atp6 and B-atp6 RNA Coding Sequences in Plants with or without Rf1a or Rf1b.

Supplemental Table 3. ANOVA of the Editing Rates of the Lines and Sites for N-atp6 mRNA.

Supplemental Table 4. ANOVA of the Editing Rates of the Lines and Sites for B-atp6 mRNA.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank H. Ma, H.M. Lam, R. Wu, R. Sung, N. Fedoroff, Y.B. Xue, M.M. Hong, O. Berking, B. Carroll, and L. Notley for helpful comments or editorial modifications to the manuscript, G. Liang, M. Gu, and Q. Qian for providing rice material, W. Sakamoto for the P35S-D1PS-GFP-Nos3′ construct, X. Liu for use of the confocal scanning microscope, and W. Chen for the analysis of variance. This work was supported by grants from the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (G1999011603), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (39980027 and 30430340), and the National Key Project of Science and Technology of China (2002AA2Z1002).

The author responsible for distribution of materials integral to the findings presented in this article in accordance with the policy described in the Instructions for Authors (www.plantcell.org) is: Yao-Guang Liu (ygliu@scau.edu.cn).

Online version contains Web-only data.

Article, publication date, and citation information can be found at www.plantcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1105/tpc.105.038240.

References

- Akagi, H., Nakamura, A., Sawada, R., and Oka, M. (1995). Genetic diagnosis of cytoplasmic male sterile cybrid plants of rice. Theor. Appl. Genet. 90 948–951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akagi, H., Nakamura, A., Yokozeki-Misono, Y., Inagaki, A., Takahashi, H., Mori, K., and Fujimura, T. (2004). Positional cloning of the rice Rf-1 gene, a restorer of BT-type cytoplasmic male sterility that encodes a mitochondria-targeting PPR protein. Theor. Appl. Genet. 108 1449–1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akagi, H., Sakamoto, M., Shinjyo, C., Shimada, H., and Fujimura, T. (1994). A unique sequence located downstream from the rice mitochondrial apt6 may cause male sterility. Curr. Genet. 25 52–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akagi, H., Yokozeki, Y., Inagaki, A., Nakamura, A., and Fujimura, T. (1996). A codominant DNA marker closely linked to the rice nuclear restorer gene, Rf-1, identified with inter-SSR fingerprinting. Genome 39 1205–1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellaoui, M., Pelletier, G., and Budar, F. (1997). The steady-state level of mRNA from the Ogura cytoplasmic male sterility locus in Brassica cybrids is determined post-transcriptionally by its 3′ region. EMBO J. 16 5057–5068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentolila, S., Alfonso, A., and Hanson, M. (2002). A pentatricopeptide repeat-containing gene restores fertility to male-sterile plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99 10887–10892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, G.G., Formanova, N., Jin, H., Wargachuk, R., Dendy, C., Patil, P., Laforest, M., Zhang, J.F., Cheung, W.Y., and Landry, B.S. (2003). The radish Rfo restorer gene of Ogura cytoplasmic male sterility encodes a protein with multiple pentatricopeptide repeats. Plant J. 35 262–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cormack, B.P., Valdivia, R.H., and Falkow, S.F. (1996). FACS-optimized mutants of the green fluorescent protein (GFP). Gene 173 33–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui, X., Wise, R.P., and Schnable, P.S. (1996). The rf2 nuclear restorer gene of male-sterile T-cytoplasm maize. Science 272 1334–1336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desloire, S., et al. (2003). Identification of the fertility restoration locus, Rfo, in radish, as a member of the pentatricopeptide-repeat protein family. EMBO Rep. 4 588–594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewey, R.E., Siedow, J.N., Timothy, D.H., and Levings III, C.S. (1988). A 13-kilodalton maize mitochondrial protein in E. coli confers sensitivity to Bipolaris maydis toxin. Science 239 293–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dombrowski, S., Brennicke, A., and Binder, S. (1997). 3′-Inverted repeats in plant mitochondrial mRNAs are processing signals rather than transcription terminators. EMBO J. 16 5069–5076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunstan, H.M., Green-Willms, N.S., and Fox, T.D. (1997). In vivo analysis of Saccharomyces cerevisiae COX2 mRNA 5′-untranslated leader functions in mitochondrial translation initiation and translational activation. Genetics 147 87–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duroc, Y., Gaillard, C., Hiard, S., Defrance, M.-C., Pelletier, G., and Budar, F. (2005). Biochemical and functional characterization of ORF138, a mitochondrial protein responsible for Ogura cytoplasmic male sterility in Brassiceae. Biochimie 87 1089–1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felsenstein, J. (1997). PHYLIP, Phylogeny Inference Package. (Seattle, WA: University of Washington).

- Gagliardi, D., and Leaver, C. (1999). Polyadenylation accelerates the degradation of the mitochondrial mRNA associated with cytoplasmic male sterility in sunflower. EMBO J. 18 3757–3766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giege, P., and Brennicke, A. (2001). From gene to protein in higher plant mitochondria. C. R. Acad. Sci. III 324 209–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gothandam, K.M., Kim, E.S., Cho, H., and Chung, Y.-Y. (2005). OsPPR1, a pentatricopeptide repeat protein of rice is essential for the chloroplast biogenesis. Plant Mol. Biol. 58 421–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson, M., and Bentolila, S. (2004). Interactions of mitochondrial and nuclear genes that affect male gametophyte development. Plant Cell 16 (suppl.), S154–S169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He, S., Abad, A., Gelvin, S.B., and Mackenzie, S.A. (1996). A cytoplasmic male sterility-associated mitochondrial protein causes pollen disruption in transgenic tobacco. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93 11763–11768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiei, Y., Ohta, S., Komari, T., and Kumashiro, T. (1994). Efficient transformation of rice (Oryza sativa L.) mediated by Agrobacterium and sequence analysis of the boundaries of the T-DNA. Plant J. 6 271–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honys, D., and Twell, D. (2003). Comparative analysis of the Arabidopsis pollen transcriptome. Plant Physiol. 132 640–652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itadani, H., Wakasugi, T., Sugita, M., Sugiura, M., Nakazono, M., and Hirai, A. (1994). Nucleotide sequence of a 28-kbp portion of rice mitochondrial DNA: The existence of many sequences that correspond to parts of mitochondrial genes in intergenic regions. Plant Cell Physiol. 35 1239–1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwabuchi, M., Kyozuka, J., and Shimamoto, K. (1993). Processing followed by complete editing of an altered mitochondrial apt6 RNA restores fertility of cytoplasmic male sterile rice. EMBO J. 12 1437–1446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadowaki, K., Suzaki, T., and Kazama, S. (1990). A chimeric gene containing the 5′ portion of atp6 is associated with cytoplasmic male-sterility of rice. Mol. Gen. Genet. 224 10–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazama, T., and Toriyama, K. (2003). A pentatricopeptide repeat-containing gene that promotes the processing of aberrant apt6 RNA of cytoplasmic male-sterile rice. FEBS Lett. 544 99–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koizuka, N., Imai, R., Fujimoto, H., Hayakawa, T., Kimura, Y., Kohno-Murase, J., Sakai, T., Kawasaki, S., and Imamura, J. (2003). Genetic characterization of a pentatricopeptide repeat protein gene, orf687, that restores fertility in the cytoplasmic male-sterile Kosena radish. Plant J. 34 407–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komori, T., Ohta, S., Murai, N., Takakura, Y., Kuraya, Y., Suzuki, S., Hiei, Y., Imaseki, H., and Nitta, N. (2004). Map-based cloning of a fertility restorer gene, Rf-1, in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Plant J. 37 315–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotera, E., Tasaka, M., and Shikanai, T. (2005). A pentatricopeptide repeat protein is essential for RNA editing in chloroplasts. Nature 433 326–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn, J., and Binder, S. (2002). RT-PCR analysis of 5′ to 3′-end-ligated mRNAs identifies the extremities of cox2 transcripts in pea mitochondria. Nucleic Acids Res. 30 439–446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn, J., Tengler, U., and Binder, S. (2001). Transcript lifetime is balanced between stabilizing stem-loop structures and degradation-promoting polyadenylation in plant mitochondria. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21 731–742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn, K., Weihe, A., and Borner, T. (2005). Multiple promoters are a common feature of mitochondrial genes in Arabidopsis. Nucleic Acids Res. 33 337–346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laser, K.D., and Lersten, N.R. (1972). Anatomy and cytology of microsporogenesis in cytoplasmic male sterile angiosperms. Bot. Rev. 38 425–454. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.M., and Yuan, L.P. (2000). Hybrid rice, genetics, breeding, and seed production. In Plant Breeding Reviews, Vol. 17, J. Janick, ed (New York: John Wiley & Sons), pp. 15–158.

- Lin, S.C., and Yuan, L.P. (1980). Hybrid rice breeding in China. In Innovative Approaches to Rice Breeding (Manila, Philippines: International Rice Research Institute), pp. 35–51.

- Liu, F., Cui, X.C., Hrner, H.T., Weiner, H., and Schnable, P.S. (2001). Mitochondrial aldehyde dehydrogenase activity is required for male fertility in maize. Plant Cell 13 1063–1078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.G., Liu, H.M., Chen, L.T., Qiu, W.H., Zhang, Q.Y., Wu, H., Yang, C.Y., Su, J., Wang, Z.H., Tian, D.S., and Mei, M.T. (2002). Development of new transformation-competent artificial chromosome vectors and rice genomic libraries for efficient gene cloning. Gene 282 247–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.-G., Shirano, Y., Fukaki, H., Yanai, Y., Tasaka, M., Tabata, S., and Shibata, D. (1999). Complementation of plant mutants with large DNA fragments by a transformation-competent artificial chromosome vector accelerates positional cloning. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96 6535–6540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.-G., and Whittier, R.F. (1995). Thermal asymmetric interlaced PCR: Automatable amplification and sequencing of insert end fragments from P1 and YAC clones for chromosome walking. Genomics 25 674–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.Q., Xu, X., Tan, Y.P., Li, S.Q., Hu, J., Huang, J.Y., Yang, D.C., Li, Y.S., and Zhu, Y.G. (2004). Inheritance and molecular mapping of two fertility-restoring loci for Honglian gametophytic cytoplasmic male sterility in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Mol. Genet. Genomics 271 586–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupold, D.S., Caoile, A.G.F.S., and Stern, D.B. (1999). The maize mitochondrial cox2 gene has five promoters in two genomic regions, including a complex promoter consisting of seven overlapping units. J. Biol. Chem. 274 3897–3903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lurin, C., et al. (2004). Genome-wide analysis of Arabidopsis pentatricopeptide repeat proteins reveals their essential role in organelle biogenesis. Plant Cell 16 2089–2103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackenzie, S., and McIntosh, L. (1999). Higher plant mitochondria. Plant Cell 11 571–585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakai, S., Noda, D., Kondo, M., and Terachi, T. (1995). High-level expression of a mitochondrial orf522 gene from the male-sterile sunflower is lethal to E. coli. Breed. Sci. 45 233–236. [Google Scholar]

- Nakazono, M., Ishikawa, M., Yoshida, K.T., Tsutsumi, N., and Hirai, A. (1996). Multiple initiation sites for transcription of a gene for subunit 1 of F1-ATPase (atp1) in rice mitochondria. Curr. Genet. 29 417–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nei, M., Gu, X., and Sitnikova, T. (1997). Evolution by birth-and death process in multigene families of the vertebrate immune system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94 7799–7806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao, Y.S. (1988). Cytohistology of cytoplasmic male sterile lines in hybrid rice. In Hybrid Rice, W.H. Smith, L.R. Bostian, and E.P. Cervantes, eds (Manila, Philippines: International Rice Research Institute), pp. 115–128.

- Rice Chromosome 10 Sequencing Consortium (2003). In-depth view of structure, activity, and evolution of rice chromosome 10. Science 300 1566–1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz-Linneweber, C., Williams-Carrier, R., and Barkan, A. (2005). RNA immunoprecipitation and microarray analysis show a chloroplast pentatricopeptide repeat protein to be associated with the 5′ region of mRNAs whose translation it activates. Plant Cell 17 2791–2804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnable, P.S., and Wise, R.P. (1998). The molecular basis of cytoplasmic male sterility and fertility restoration. Trends Plant Sci. 3 175–180. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, A., Wyatt, S., Tsou, P.L., Robertson, D., and Allen, N.S. (1999). Model system for plant cell biology: GFP imaging in living onion epidermal cells. Biotechniques 26 1125, 1128–1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinjyo, C. (1969). Cytoplasmic genetic male sterility in cultivated rice, Oryza sativa L. II. The inheritance of male sterility. Jpn. J. Genet. 44 149–156. [Google Scholar]

- Shinjyo, C. (1975). Genetical studies of cytoplasmic male sterility and fertility restoration in rice, Oryza sativa L. Sci. Bull. Coll. Agric. Univ. Ryukyus 22 1–57. [Google Scholar]

- Small, I.D., and Peeters, N. (2000). The PPR motif – A TPR-related motif prevalent in plant organellar proteins. Trends Biochem. Sci. 25 46–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strimmer, K., and von Haeseler, A. (1996). Quartet puzzling: A quartet maximum likelihood method for reconstructing tree topologies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 13 964–969. [Google Scholar]

- Sze, H., Padmanaban, S., Cellier, F., Honys, D., Cheng, N.-H., Bock, K.W., Conéjéro, G., Li, X., Twell, D., Ward, J.M., and Hirschi, K.D. (2004). Expression patterns of a novel AtCHX gene family highlight potential roles in osmotic adjustment and K+ homeostasis in pollen development. Plant Physiol. 136 2532–2547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang, H.V., Pring, D.R., Shaw, L.C., Salazar, R.A., Muza, F.R., Yan, B., and Schertz, K.F. (1996). Transcript processing internal to a mitochondrial open reading frame is correlation with fertility restoration in male-sterile sorghum. Plant J. 10 123–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, J.D., Gibson, T.J., Plewniak, F., Jeanmougin, F., and Higgins, D.G. (1997). The Clustal-X windows interface: Flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 25 4876–4882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Virmani, S.S. (2003). Advances in hybrid rice research and development in the tropics. In Hybrid Rice for Food Security, Poverty Alleviation, and Environmental Protection. Proceedings of the 4th International Symposium on Hybrid Rice, May 14–17, 2002, Hanoi, Vietnam. S.S. Virmani, C.X. Mao, and B. Hardy, eds (Los Baños, Philippines: International Rice Research Institute), pp. 7–20.

- Wen, L., Ruesch, K.L., Ortega, V.M., Kamps, T.L., Gabay-Laughnan, S., and Chase, C.D. (2003). A nuclear restorer-of-fertility mutation disrupts accumulation of mitochondrial ATP synthase subunit α in developing pollen of S male-sterile maize. Genetics 165 771–779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise, R.P., and Pring, D.R. (2002). Nuclear-mediated mitochondrial gene regulation and male fertility in higher plants: Light at the end of the tunnel? Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99 10240–10242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Z.H., McCouch, S.R., Kinoshita, T., Sato, S., and Tanksley, S.D. (1995). Association of morphological and RFLP markers in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Genome 38 566–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, G., Bharaj, T.S., Lu, Y., Virmani, S., and Huang, N. (1997). Mapping of the Rf3 nuclear fertility-restoring gene for WA cytoplasmic male sterility in rice using RAPD and RFLP markers. Theor. Appl. Genet. 94 27–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q., Liu, Y.G., Zhang, G., and Mei, M. (2002). Molecular mapping of the fertility restorer gene Rf4 for WA cytoplasmic male sterility in rice. Acta Genet. Sinica 29 1001–1004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y. (2000). Biology of the Male Sterility in Rice. (Wuhan, China: Wuhan University Press).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.