Abstract

The aim of the present investigation was to elucidate further the importance of p38 MAPK (mitogen-activated protein kinase) in nitric oxide- and cytokine-induced β-cell death. For this purpose, isolated human islets were treated with d-siRNA (diced small interfering RNA) and then exposed to the nitric oxide donor DETA/NONOate [2,2′-(hydroxynitrosohydrazono)bis-ethanamine]. We observed that cells treated with p38α-specific d-siRNA, but not with d-siRNA targeting GL3 (a firefly luciferase siRNA plasmid) or PKCδ (protein kinase Cδ), were protected against nitric oxide-induced death. This was paralleled by an increased level of Bcl-XL (B-cell leukaemia/lymphoma-X long). For an in-depth study of the mechanisms of p38 activation, MKK3 (MAPK kinase 3), MKK6 and their dominant-negative mutants were overexpressed in insulin-producing RIN-5AH cells. In transient transfections, MKK3 overexpression resulted in increased p38 phosphorylation, whereas in stable MKK3-overexpressing RIN-5AH clones, the protein levels of p38 and JNK (c-Jun N-terminal kinase) were decreased, resulting in unaffected phospho-p38 levels. In addition, a long-term MKK3 overexpression did not affect cell death rates in response to the cytokines interleukin-1β and interferon-γ, whereas a short-term MKK3 expression resulted in increased cytokine-induced RIN-5AH cell death. The MKK3-potentiating effect on cytokine-induced cell death was abolished by a nitric oxide synthase inhibitor, and MKK3-stimulated p38 phosphorylation was enhanced by inhibitors of phosphatases. Finally, as the dominant-negative mutant of MKK3 did not affect cytokine-induced p38 phosphorylation, and as wild-type MKK3 did not influence p38 autophosphorylation, it may be that p38 is activated by MKK3/6-independent pathways in response to cytokines and nitric oxide. In addition, it is likely that a long-term increase in p38 activity is counteracted by both a decreased expression of the p38, JNK and p42 genes as well as an increased dephosphorylation of p38.

Keywords: apoptosis, interleukin-1β (IL-1β), insulin-producing cell, MKK3, nitric oxide, p38 MAPK

Abbreviations: ASK, apoptosis signal-regulating kinase; ATF, activating transcriptional factor; Bcl-XL, B-cell leukaemia/lymphoma-X long; CREB, cAMP-response-element-binding protein; DETA/NONOate, 2,2′-(hydroxynitrosohydrazono)bis-ethanamine; siRNA, small interfering RNA; d-siRNA, diced siRNA; ERK, extracellular-signal-regulated kinase; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; GFP, green fluorescent protein; hsp25, heat-shock protein 25; IFN-γ, interferon-γ; Ig, immunoglobulin; IL-1β, interleukin-1β; iNOS, inducible nitric oxide synthase; JNK, c-Jun N-terminal kinase; L-NMMA, NG-monomethyl-L-arginine; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; MAP3K, MAPK kinase kinase; MAPKAP-K2, MAPK-activated protein kinase 2; MAPKK, MAPK kinase; MEK, MAPK/ERK kinase; MEKK, MEK kinase; MSK1, mitogen- and stress-activated kinase 1; NF-κB, nuclear factor κB; PKC, protein kinase C; RNAi, RNA interference; SAPK, stress-activated protein kinase; TGF-β, transforming growth factor-β; TAK1, TGF-β-activated protein 1; TAB1, TAK1-binding protein; TNF-α, tumour necrosis factor-α

INTRODUCTION

The intra-islet release of proinflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1β (interleukin-1β), IFN-γ (interferon-γ) and TNF-α (tumour necrosis factor-α), may be a possible reason for dysfunction and damage of β-cells in Type I (insulin-dependent) diabetes [1]. As cytokines, particularly the combination of IL-1β and IFN-γ, induce β-cell apoptosis and necrosis in vitro [2], these molecules have been proposed to not only control immune cell activity, but also to exert a direct toxic effect on the insulin-producing cells. In rodents, IL-1β and IFN-γ kill β-cells mainly by iNOS (inducible nitric oxide synthase), which in turn leads to inhibition of mitochondrial ATP production [3], a decrease in mitochondrial membrane potential [4], endoplasmic reticulum stress [5] and p53 activation [6].

Cytokines also activate the ERKs (extracellular-signal-regulated kinases), the JNKs (c-Jun N-terminal kinases) and p38 MAPKs (mitogen-activated protein kinases) (p38) [7–9]. Four p38 isoforms have been identified: p38α, p38β, p38γ and p38δ. These isoforms are defined by the common TGY (threonine-proline-tyrosine) motif and have significant homology with each other at the amino acid level [10]. Nevertheless, they are considered to differ in substrate specificity and therefore also in function [11]. The p38α and p38β isoforms are expressed in most tissues, whereas expression of p38γ is limited to skeletal muscle and that of p38δ to small intestine, lung, pancreas, testis and kidney [12].

To our knowledge, it is not known how p38 in insulin-producing cells is activated in response to cytokines or nitric oxide. In other cell types, however, it is known that the p38, ERK and JNK families are organized into partially discrete and parallel signalling cascades in which a MAP3K (MAPK kinase kinase) phosphorylates and activates a dual-specificity MAPKK (MAPK kinase; also known as MKK and MEK), which then activates a MAPK by phosphorylating both threonine and tyrosine residues in the TGY motif. More specifically, it has been demonstrated that p38 and JNK are phosphorylated and activated by the MAPKKs MKK3/6 and MKK4/7 respectively which in turn are activated by upstream MAP3Ks and MAP4Ks, such as MEKK1–MEKK4 [MEKK stands for MEK (MAPK/ERK kinase) kinase], TAK1 (TGF-β-activated protein 1, where TGF-β stands for transforming growth factor-β), MLK (MAPK kinase kinase 9), DLK (dual leucine zipper kinase), ASK (apoptosis signal-regulating kinase), Tpl-2 (tumour-progression locus-2 protein kinase) and SPAK (Ste20/SPS1 related kinase) [13].

In addition to the general pathway for MAPK activation described above, MKK3/6-independent pathways have recently been proposed. For example, it has been shown that TAB1 (TAK1-binding protein) promotes p38 autophosphorylation by a direct interaction with the MAPK [14]. Furthermore, a Ras/RalGEF/p38 (where RalGEF stands for Ral guanine nucleotide-exchange factor) pathway has been described in [15] and it is also possible that Src and PKC (protein kinase C) activation lead to p38 phosphorylation by an MKK3/6-independent mechanism [16,17]. However, the details of these pathways are largely unknown.

Sustained and pronounced activation of p38 is considered to result in apoptosis [18]. Possible downstream targets to p38 that mediate this effect could be p53 [19], NF-κB (nuclear factor κB) [20], different isoforms of PKC [21] and caspases [22]. It has also been shown that p38 activation increases the expression of FasL (Fas ligand) [23] and iNOS [24]. In insulin-producing cells, cytokine-induced activation of p38 promotes increased phosphorylation of hsp25 (heat-shock protein 25), MAPKAP-K2 (MAPK-activated protein kinase 2), MSK1 (mitogen- and stress-activated kinase 1), ATF2 (activating transcriptional factor 2) and CREB (cAMP-response-element-binding protein) [8,9] and induction of iNOS gene expression [8]. In addition, pharmacological inhibition of p38 partially prevents cytokine-induced islet cell death [9], pointing to a possible role of p38 in the pathogenesis of Type I diabetes.

The aim of the present study was to investigate more closely the putative role of p38 in cytokine- and nitric oxide-induced β-cell dysfunction. We observe that a genetic down-regulation of p38α results in lowered sensitivity to nitric oxide. In addition, a long-term overexpression of MKK3 perturbed neither the viability of insulin-producing cells nor the levels of phosphorylated p38. A short-term MKK3 overexpression, however, increased both p38 phosphorylation and cell death. As the dominant-negative mutant of MKK3 decreased neither cytokine-induced p38 phosphorylation nor cell death, we propose that cytokine- and nitric oxide-induced p38 phosphorylation does not require the MKK3/6 pathway.

EXPERIMENTAL

Materials

The chemicals were obtained from the following sources: RPMI 1640, fetal bovine serum, L-glutamine, Hanks balanced salt solution, trypsin-EDTA, okadaic acid, G418 (Geneticin) and propidium iodide were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, U.S.A.). SB203580 [4-(4-fluorophenyl)-2-(4-methylsuphinylphenyl)-5-(4-pyridyl) imidazole] and anti-MEK6 (C-terminal 320–334) antibodies were from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA, U.S.A.). Recombinant human IL-1β, recombinant mouse IFN-γ and recombinant human TNF-α were from PeproTech EC Ltd (London, U.K.). Sodium orthovanadate was from E. Merck (Darmstadt, Germany). Polyclonal antibodies raised against p38 MAPK, SAPK/JNK (where SAPK stands for stress-activated protein kinase), phospho-(Thr180/Tyr182) p38, phospho-(Thr183/Tyr185) SAPK/JNK and phospho-(Thr202/Tyr204) p42/p44 were all from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA, U.S.A.). iNOS antibody was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, U.S.A.). Horseradish peroxidase-linked goat anti-rabbit Ig (immunoglobulin) was from Amersham Biosciences. Polyclonal ERK1 (C-16) and MEK3 (I-20) antibodies were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. The pCDNA3-MKK3/6 wild-type and pCDNA3/6 mutant constructs were kindly provided by Dr Per Gerwins (Department of Genetics and Pathology, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden). In the mutant constructs, Ser189/Thr193 and Ser207/Thr211 were changed to alanine residues in MKK3 and MKK6 respectively [25].

Cell culture

Insulin-producing rat insulinoma RIN-5AH cells were kindly provided by Professor Thomas Mandrup-Poulsen at Steno Diabetes Center (Gentofte, Denmark). The cells were used at passage numbers 20–30, trypsinized every 3–5 days and subcultured (5×105 cells per 50 mm dish) in RPMI 1640 containing 11.1 mM glucose supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum, 2 mM L-glutamine and penicillin (100 units/ml) at 37 °C in humidified air with 5% CO2. Rat islets were collagenase-isolated from Spraque–Dawley rats (local colony at Biomedical Center) and cultured in 50 mm non-attachment Sterilin dishes (Bibby Sterilin, Stone Staffs, U.K.) in the RPMI 1640 medium described above. Human islets were kindly provided by Dr Olle Korsgren (Departments of Radiology, Oncology and Clinical Immunology, Uppsala University). The islets were cultured in the same medium as described above with the exception that the glucose concentration was lowered to 5.6 mM. The β-cell percentage was determined by flow cytometry and was routinely above 50% (results not shown).

RNA isolation and cDNA synthesis

Total RNA was isolated from RIN-5AH cells, isolated rat islets and murine brain endothelia (IBE) cells using the Ultra-spec™ RNA Isolation System reagent (Biotecx Laboratories, Houston, TX, U.S.A.). RNA (2 μg) was used for cDNA synthesis. cDNA was synthesized using the M-MuLV reverse transcriptase (Finnzymes, Espoo, Finland) and oligo-dT primers according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Real-time PCR

PCR amplification was performed using the Lightcycler instrument (Roche Diagnostics, Lewes, U.K.) and the LightCycler FastStart DNA Master SYBR Green I kit (Roche Diagnostics) with GAPDH (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase) primers and primers for the different isoforms of the p38 MAPK (Table 1). The cycling parameters were 95 °C for 9 min (one cycle); 95 °C for 15 s, 56 °C for 10 s and 72 °C for 12 s (30 cycles).

Table 1. Primers used for PCR detection of p38 isoforms.

| Forward 5′–3′ | Reverse 5′–3′ | |

|---|---|---|

| p38α (rat) | CTACGGCTCGGTGTGTGCTGC | CTGAACGTGGTCATCGGTAAGC |

| p38β (mouse) | GTGTACCTCGTGACGACCCTGA | GCAGTCCTCGTTCACCGCTAC |

| p38γ (mouse) | GTTGGCTCTGGTGCCTATGGT | CAGATCAGTGCCCATGAATGGC |

| p38δ (rat) | CGGTGTGCTCGGCCATCGACA | TCTTGGAAGTTTCGAACGGAAGT |

| GAPDH (rat, mouse and human) | ACCACAGTCCATGCCATCAC | TCCACCACCCTGTTGCTGTA |

Semi-quantitative data for p38 expression were calculated using the following formula: 2(crossing point GAPDH−crossing point p38). The different groups were then expressed as percentage of p38α in RIN-5AH cells. PCR products were analysed by 2% (w/v) agarose-gel electrophoresis and ethidium bromide staining to verify that correct PCR products were obtained.

d-siRNA (diced small interfering RNA)-mediated down-regulation of p38α in human islet cells

Human islets, in groups of 100, were trypsinized (0.5%) for 5 min at 37 °C and then treated with DNase I (30 units/ml) for 2 min. The resulting free islet cells were placed in non-attachment plates and transfected with 100 ng of d-siRNA directed against human p38α, PKCδ or GL3 (a firefly luciferase siRNA plasmid) (control). We have recently observed that this procedure results in a 70–80% decrease in islet cell gene expression [26]. d-siRNA directed against the 5′-end of the coding region of the human p38α gene, the 5′-end of the coding region of the human PKCδ gene and the 5′-end of the coding region of the Photinus Pyralis GL3 luciferase gene was synthesized as described previously [27]. In vitro transcription templates for p38α (GenBank® accession no. NM_001315) and PKCδ (GenBank® accession no. NM_006254) were amplified from HeLa cell cDNA using the following primers: p38α sense, 5′-GCGTAATACGACTCACTATAGGCACTAGGTGGTACAGGGCTC-3′; p38α antisense, 5′-GCGTAATACGACTCACTATAGGCAGGACTCCATCTCTTCTTGG-3′; PKCδ sense, 5′-GCGTAATACGACTCACTATAGGATGGCGCCGTTCCTGC-3′; PKCδ antisense, 5′-GCGTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGATGGCAGCGTTACATTGCCTG-3′. The in vitro transcription template for GL3 control was amplified from the GL3 control vector (U47296.2; Promega, Madison, WI, U.S.A.) with the following primers: sense, 5′-GCGTAATACGACTCACTATAGGAACAATTGCTTTTACAGATGC-3′; and antisense, 5′-GCGTAATACGACTCACTATAGGAGGCAGACCAGTAGATCC-3′. T7 phage polymerase promoter is shown in boldface.

d-siRNA was introduced into islet cells during a 2 h incubation period using 4 μl of Lipofectamine™ 2000 (Invitrogen, San Diego, CA, U.S.A.) in 200 μl of serum-free culture medium [26]. The transfection medium was then replaced by full culture medium and the cells were cultured for another 24 h. DETA/NONOate [2,2′-(hydroxynitrosohydrazono)bis-ethanamine] (2 mM) was added to some groups and, on the next day, cells were stained with propidium iodide (20 μg/ml) and Hoechst (5 μg/ml) for fluorescence microscopic quantification of islet cell death. In some experiments, cells were harvested 2 days after transfection for immunoblot analysis of p38α and JNK2 or Bcl-XL (B-cell leukaemia/lymphoma-X long) and Bax using antibodies from Santa Cruz Biotechnology.

Overexpression of MKK3 and MKK6 in RIN-5AH cells

For stable expression of MKK3/6, RIN-5AH cells were transfected with 2 μg of pcDNA3-MKK3wt, pcDNA3-MKK3m, pcDNA3-MKK6wt or pcDNA3-MKK6m using Lipofectamine™ reagent (Invitrogen) as described by the manufacturer. G418 (300 μg/ml) was added 1 day after the transfection. On day 6, the G418 dose was reduced to 150 μg/ml. G418-resistant clones were picked after 2 weeks and analysed for expression of MKK3 and MKK6 by immunoblot analysis.

For transient expression, 2–3×106 RIN-5AH cells, which had been seeded the day before, were transfected with 0.5 μg of pEGFP-C1 (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA, U.S.A.) +2 μg of pcDNA3-MKK3/6 using 20 μl of Lipofectamine™ (Invitrogen). Control cells were transfected with 2.5 μg of pEGFP-C1 only. The transfection mixture (200 μl) was dropped on to the cells that were in 1.5 ml of serum-free RPMI 1640. The cells were centrifuged at 600 g for 10 min in a swing-out rotor. After 60 min at 37 °C, the transfection medium was replaced with full culture medium. On the day after transfection, GFP (green fluorescent protein)-positive cells were sorted using a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA, U.S.A.). GFP-positive cells were identified by gating a region with high FL-1 (fluorescence channel 1) intensity and normal size [FSC (forward scatter)]. In typical experiments, 5–10% of the cells were GFP-positive and 200000–250000 cells/group were collected. This results in an enrichment of the GFP-positive cells to >70% [28]. The sorted cells were then re-plated in 24-well plates and cultured for another 24–72 h.

Immunoblot analysis

RIN-5AH cells (1×105) were washed in cold PBS and lysed in SDS–2-mercaptoethanol sample buffer containing 1 mM PMSF. Samples were then sonicated, boiled, separated on SDS/9% polyacrylamide gels and electroblotted on to nitrocellulose filters. The filters were incubated with total p38 MAPK, total SAPK/JNK or total p42/p44 antibodies diluted 1:1000 in PBS supplemented with 2.5% (w/v) BSA. The filters were also incubated with phospho-specific p38, phospho-specific SAPK/JNK and phospho-specific p42/44 antibodies diluted 1:1000 in Tris-buffered saline supplemented with 2.5% BSA. In some experiments, filters were probed for MKK3, MKK6 and iNOS using rabbit anti-human MKK3 (MEK3), rabbit anti-human MKK6 (MEK6) and mouse anti-mouse iNOS (NOS2) antibodies. Stripping between the antibodies was performed by incubating for 40 min at 55 °C in 2% (w/v) SDS and 0.1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol. Horseradish peroxidase-linked goat anti-rabbit Ig was used as a second layer. The immunodetection was performed as described for the ECL® (enhanced chemiluminescence) immunoblotting detection system (Amersham Biosciences). The intensities of the bands were quantified by densitometric scanning using Kodak Digital Science ID software (Eastman Kodak, Rochester, NY, U.S.A.).

Nitrite determination

A solution (10 μl) of 0.5% naphylethylenediamine dihydrochloride, 5% (w/v) sulphanilamide and 25% concentrated H3PO4 was added to duplicate samples (2×80 μl) of the culture medium. The absorbance at 546 nm was measured in a Beckman DU-62 spectrophotometer against a standard curve.

Cell viability

RIN-5AH cells transiently or stably expressing GFP, MKK3wt, MKK3m, MKK6wt and MKK6m were stained with propidium iodide (20 μg/ml) for 10 min at 37 °C. After careful washing, cells were trypsinized and analysed for red fluorescence (FL-3) using flow cytometry. Cells with intermediate fluorescence were gated as apoptotic and cells with high fluorescence were gated as necrotic [29]. As the percentage of necrotic cells was very low and not affected by the different treatments (results not shown), we only show the rates of apoptosis.

RESULTS

P38 isoform mRNA expression patterns in insulin-producing cells

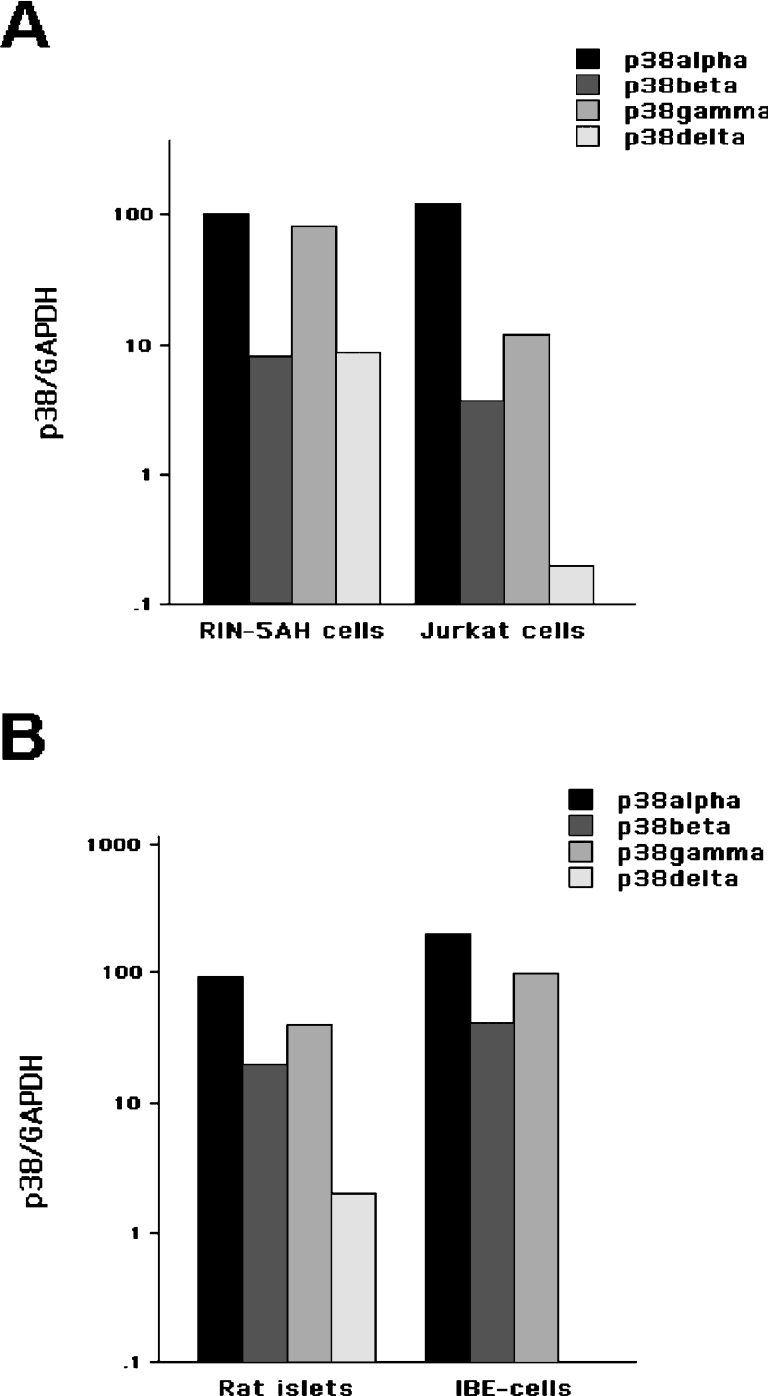

To our knowledge, it is not known which isoforms of p38 are expressed in insulin-producing cells. We therefore aimed at determining the mRNA expression pattern of p38 MAPK isoforms in RIN-5AH cells and rat islets and to compare the expression patterns in these cells with those of T-lymphocytes (Jurkat) and endothelial IBE cells respectively. Real-time PCR semi-quantification using isoform-specific primers indicated that all p38 isoforms could be detected in insulin-producing cells (Figures 1A and 1B). Assuming that PCR amplification of the different isoforms is equally efficient, it appears that the p38α isoform is the most abundant isoform in all of the cell types investigated (Figures 1A and 1B). In rat islets, the expression levels of p38α, p38β and p38γ were quite similar to those of IBE cells, whereas the expression of p38δ, which was present in islet cells, was undetectable in IBE cells (Figure 1B). Also, in Jurkat cells, the expression of p38δ was considerably lower than in RIN-5AH cells (Figure 1A). We also analysed the rat islet isoform expression pattern in response to 24 h cytokine stimulation. In these experiments, we observed a modest increase (2–4-fold) in p38α, p38β and p38δ (results not shown).

Figure 1. p38 isoform expression patterns in response to cytokine stimulation.

(A) Total RNA was purified from RIN-5AH cells and human T-lymphocyte Jurkat cells and real-time PCR analysis of p38α, p38β, p38γ and p38δ was performed. Data are p38/GAPDH ratios expressed as percentage of p38α in RIN-5AH cells not exposed to cytokines. Results are means for two different experiments. (B) Real-time PCR analysis of p38α, p38β, p38γ and p38δ in isolated rat islets and mouse endothelial IBE cells.

Effect of p38α d-siRNA on nitric oxide-induced human islet cell death

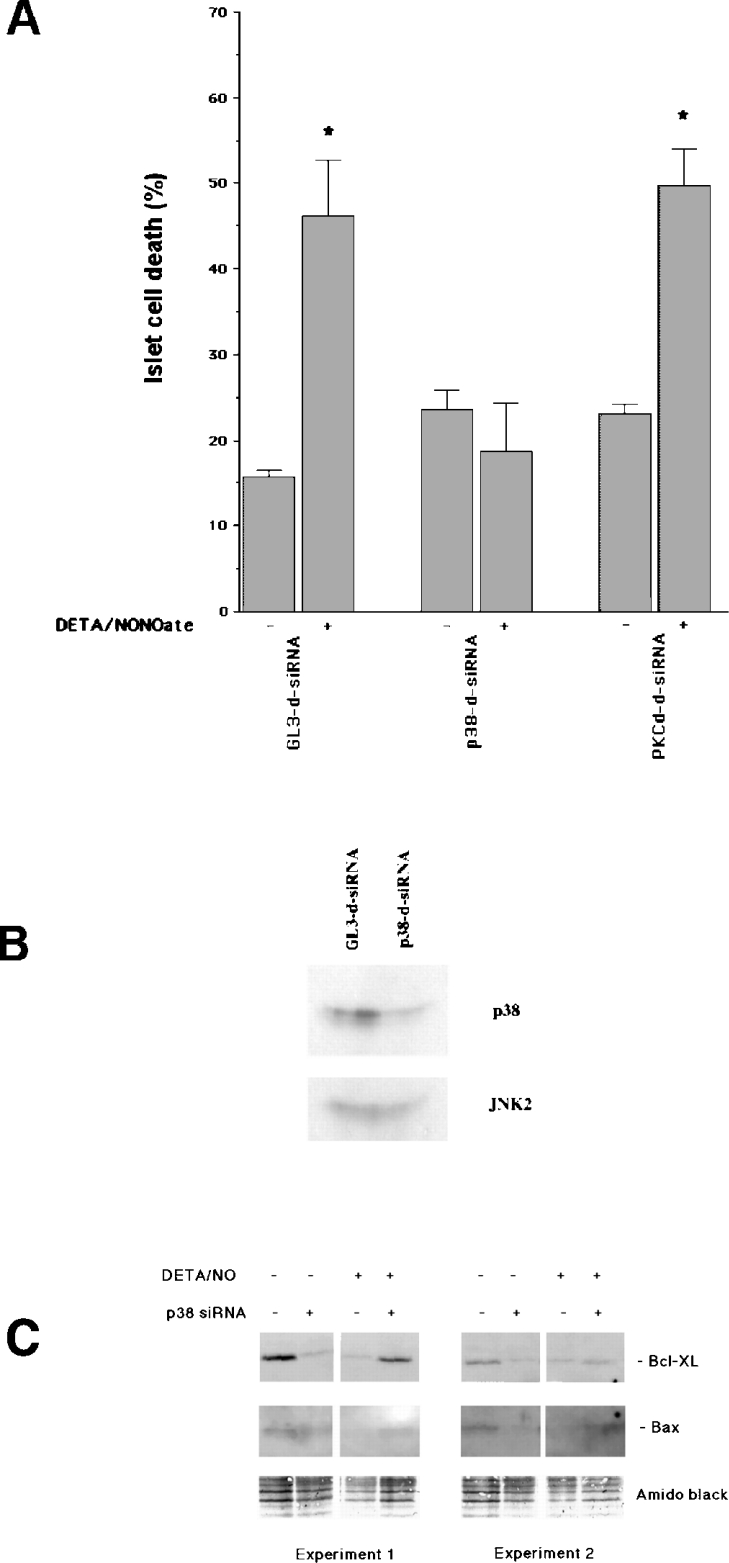

Pharmacological inhibition of p38 has previously resulted in partial protection against the cytokines IL-1β and IFN-γ [9]. Having presently found that p38α appears to be the most prominent p38 isoform in insulin-producing cells, we down-regulated p38α in human islet cells using the RNAi (RNA interference) technique to see whether p38 plays a direct role in cytokine- or nitric oxide-induced β-cell death. As cytokines require 5–7 days to promote apoptosis in human islet cells [30], and siRNA-induced silencing does not last for 7 days [26], we instead exposed the d-siRNA-transfected cells to the nitric oxide donor DETA/NONOate, which kills islet cells in only 1 day (Figure 2A). Indeed, the islet cell viability was only 55% after a 24 h exposure to DETA/NONOate in cells transfected with control siRNA (Figure 2A). However, islet cells transfected with d-siRNA directed against human p38α did not exhibit increased rates of death in response to the nitric oxide donor (Figure 2A). To verify that the p38α-specific d-siRNA actually down-regulated islet cell levels of p38α, we performed an immunoblot analysis of p38α and JNK2 (Figure 2B). These experiments demonstrated lowered p38α levels, but not JNK2 levels, in response to the p38α-specific d-siRNA. We also analysed whether d-siRNA specific for human PKCδ affected nitric oxide-induced islet cell death. In this case, however, no protection against nitric oxide could be observed (Figure 2A).

Figure 2. p38α mediates NO-induced human islet cell death.

(A) Human islet cells were dispersed and transfected with d-siRNA against GL3 (control), p38α or PKCδ. On the next day, 2 mM DETA/NONOate was added and the cells were incubated for another 24 h. Cells were then stained with propidium iodide and Hoechst and inspected with a fluorescence microscope. Cell nuclei with red staining (necrosis), white condensed or fragmented staining (apoptosis) and blue staining (viable cells) were counted. Results are combined rates of apoptosis and necrosis and are expressed as percentage of the total cell number. Results are means±S.E.M. for four separate observations. *P<0.05 versus the corresponding control using Student's paired t test. (B) Two days after transfection of dispersed human islet cells with GL3-d-siRNA or p38-d-siRNA, the cells were lysed in SDS sample buffer and analysed for p38α and JNK2 expression using the immunoblot technique. The immunoblot is representative of two separate experiments. (C) Two days after transfection of dispersed islet cells with GL3-d-siRNA or p38-d-siRNA and 1 day after addition of 2 mM DETA/NONOate to some of the groups, the cells were lysed in SDS sample buffer and analysed for Bcl-XL and Bax expression using the immunoblot technique. Two representative experiments are shown. Protein loading is visualized by Amido Black staining.

We also studied whether d-siRNA-targeted down-regulation of p38α affected the levels of the Bcl-2 family members Bcl-XL and Bax. In these experiments, we observed that the anti-apoptotic Bcl-XL was down-regulated in response to DETA/NONOate and p38α d-siRNA (Figure 2C). When DETA/NONOate was added to p38 d-siRNA-treated islet cells, however, there was a partial restoration of Bcl-XL levels. Bax-specific immunoreactivity was weaker than Bcl-XL, but seemed to co-vary with Bcl-XL. These results indicate that p38α might influence islet cell death by controlling the levels of Bcl-2 family members.

Effect of stable MKK3/6 overexpression on the levels of p38, JNK2 and p42/p44

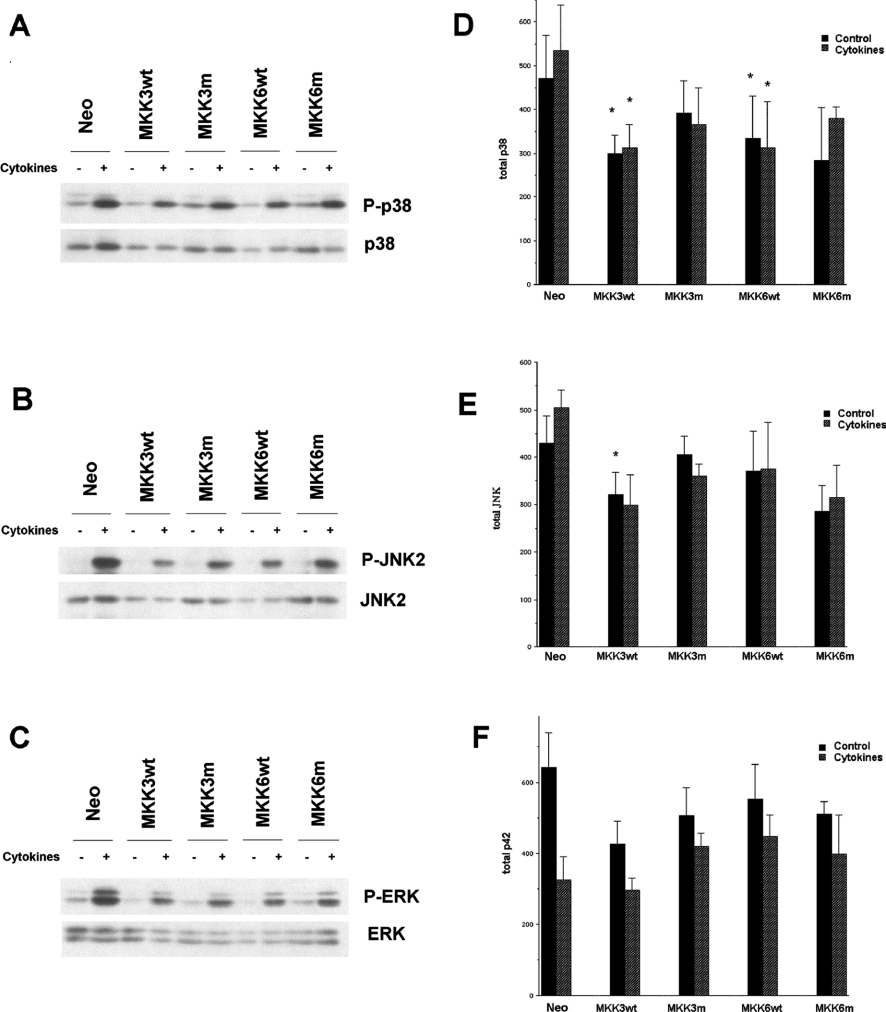

Having observed that p38α mediates islet cell sensitivity to nitric oxide, we next investigated whether cytokine- or nitric oxide-induced p38 activation requires the MKK3/6 pathway. For this purpose, stable RIN-5AH cell clones (at least three different clones per group) expressing human wild-type MKK3/6 (MKK3/6wt) or human dominant-negative mutant MKK3/6 (MKK3/6m) were selected and analysed. As previously observed [8,9,31], the combination of IL-1β and IFN-γ promoted p38, JNK2 and ERK phosphorylation (Figure 3). Surprisingly, we observed that stable MKK3/6wt overexpression increased neither basal nor cytokine-induced p38, JNK2 and p42/44 phosphorylation (Figures 3A–3C). Also, MKK3/6m expression did not affect p38, JNK2 or ERK phosphorylation (Figures 3A–3C). Instead, we detected an MKK3wt- and MM6wt-induced decrease in the total levels of p38 and JNK2 (Figures 3D and 3E). Total JNK2 and p38 levels were not significantly decreased by the MKK3/6 mutants. The ERK levels were not significantly affected by MKK3wt and MKK6wt, but were instead lowered by the cytokine treatment (P<0.05 using two-way ANOVA for repeated measurements). These results suggest that cytokine treatment or long-term MKK3/6 overexpression activates feedback mechanisms that decrease the total levels of p38, JNK2 and ERK.

Figure 3. p38, JNK2 and p44/42 are not hyperphosphorylated in MKK3/6-overexpressing RIN-5AH clones.

MKK3wt, MKK3m, MKK6wt or MKK6m clones (at least three different clones per group) were stimulated with IL-1β (50 units/ml) and IFN-γ (1000 units/ml) (cytokines) for 30 min, lysed and analysed by immunoblotting with phospho-specific antibodies recognizing phosphorylated p38-MAPK (A, D), JNK2 (B, E) and p44/42-ERK (C, F) and total p38, JNK2 and p44/42. The immunoblots shown in (A–C) are representative of five experiments and the means±S.E.M. for these experiments are shown in (D–F). *P<0.05 using ANOVA and Student–Newman–Keuls post-ANOVA test. Abbreviation: Neo, neomycin-resistance.

Lack of effect of stable MKK3/6 overexpression on cytokineinduced RIN-5AH cell death and nitric oxide production

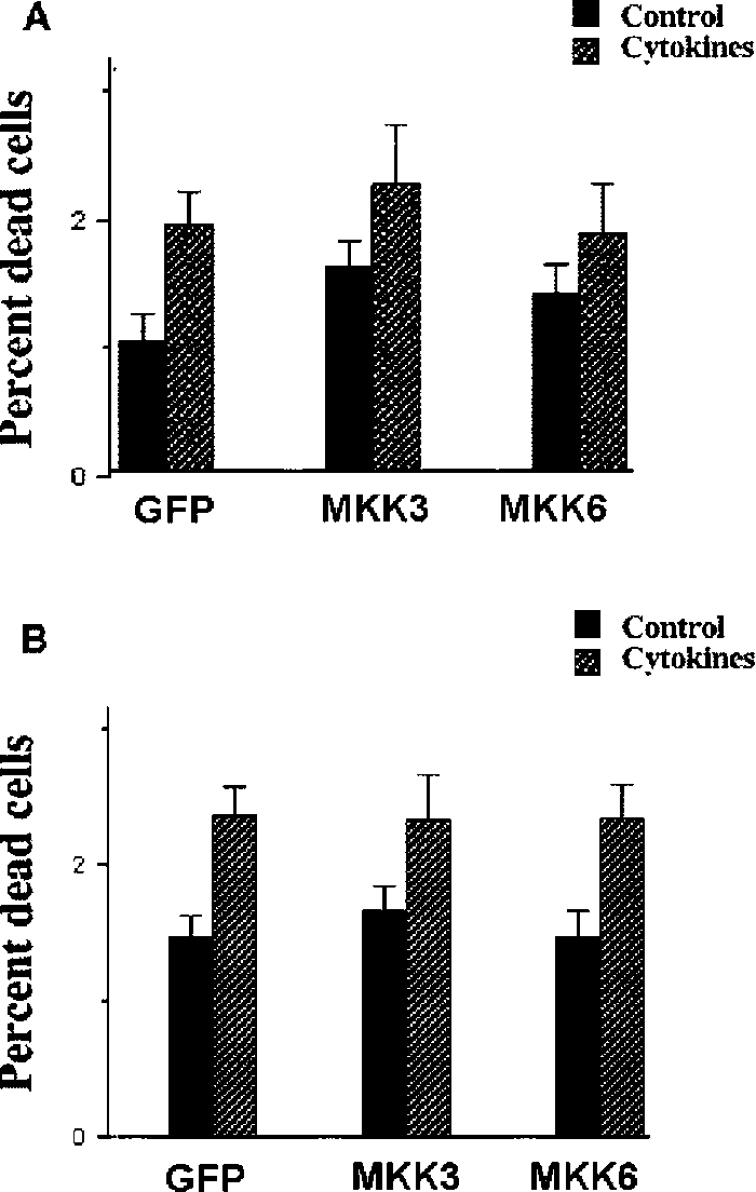

To investigate whether a long-term MKK3/6 overexpression affects cytokine-induced nitric oxide production and cell death, stable MKK3/6wt clones were exposed to IL-1β and IFN-γ for 24 h and then analysed for propidium iodide uptake. The different clones responded to the cytokines with increased cell death, but neither basal nor cytokine-induced cell death rates were affected by MKK3 or MKK6 expression (Figure 4A). Also, cytokine-induced nitrite levels were unaffected by MKK3/6 overexpression (results not shown). As cytokines promote a low rate of β-cell death in the absence of nitric oxide production [32], we exposed the clones to cytokines in the presence of the iNOS inhibitor L-NMMA (NG-monomethyl-L-arginine), which resulted in no detectable nitric oxide production (results not shown). In this case, a 3 day exposure resulted in increased rates of cell death, but cell death was not affected by MKK3/6 overexpression (Figure 4B).

Figure 4. Lack of effect of stable expression of MKK3/MKK6 on cytokine-induced apoptosis and nitric oxide production.

(A) Stable RIN-5AH clones were exposed to cytokines IL-β (50 units/ml) and IFN-γ (1000 units/ml) at 37 °C for 24 h. Cells were then stained with propidium iodide and analysis of cell viability was performed using the FACSCalibur flow cytometer. Results are presented as percentage dead cells of total cell count. Results shown are means±S.E.M. for six independent experiments. (B) L-NMMA (2 mM) was added to all stable clones. At the same time, the cytokines IL-1β (50 units/ml), IFN-γ (1000 units/ml) and TNF-α (1000 units/ml) were added to some groups. Cells were incubated at 37 °C for 72 h and cell viability was analysed using flow cytometry. Results are presented as percentage dead cells of total cell count. Results shown are means±S.E.M. for five independent experiments.

Effect of transient MKK3/6 overexpression on the basal level of p38 phosphorylation

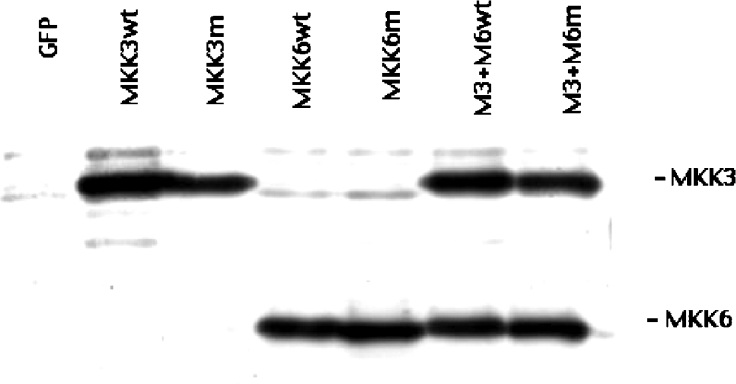

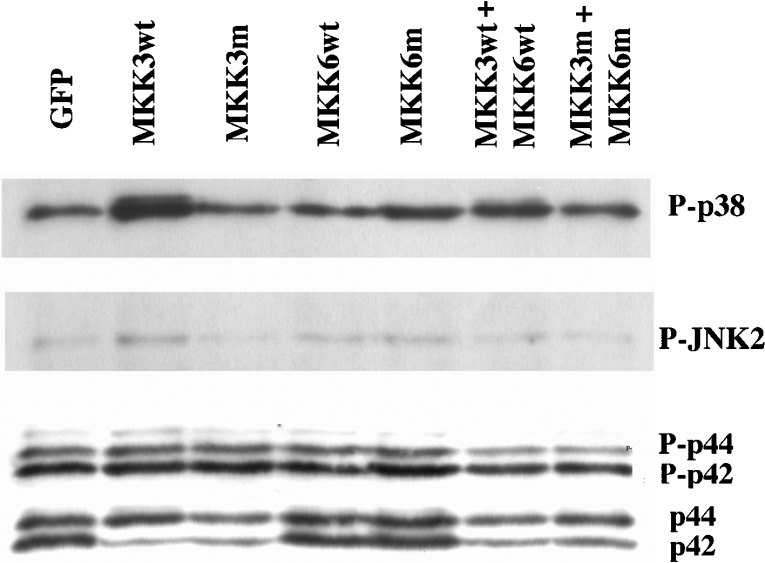

In view of our finding that stable MKK3/6 overexpression results in a compensatory down-regulation of p38 and JNK2 gene expression, we next attempted to overexpress MKK3/6 transiently (24–48 h) by lipofection and FACS of GFP-positive cells. Using this approach, we obtained >70% GFP-positive cells (results not shown) and strong MKK3/6 immunoreactivity (Figure 5). Interestingly, no MKK3 or MKK6 immunoreactivity could be observed in GFP-transfected cells (Figure 5), indicating that MKK3/6 expression is very low in wild-type RIN-5AH cells. When immunostaining MKK3-transfected cells, we observed an increased MKK3-specific immunofluorescence, which was located at the nucleus and the perinuclear region (results not shown). The increased MKK3wt expression was paralleled by an enhanced phosphorylation of p38, but not of JNK2 or ERK (Figure 6). Somewhat surprisingly, the basal phosphorylation p38 level was not affected by expression of the MKK3/6 dominant-negative mutants (Figure 6). Instead, we observed a trend to lower p42 ERK levels in response to both MKK3wt and MKK3m (Figure 6). These results suggest that although MKK3wt phosphorylates p38 in RIN-5AH cells, inhibition of MKK3 does not perturb the basal p38 phosphorylation level.

Figure 5. Transient overexpression of MKK3 and MKK6 in sorted RIN-5AH cells.

RIN-5AH cells were transfected with pEGFP-C1 and the indicated plasmids using Lipofectamine™. On the next day, the GFP-positive cells were FACS-sorted and re-plated. Cells were analysed, 24 h later, for MKK3 and MKK6 overexpression by immunoblotting. The immunoblot is representative of four experiments.

Figure 6. Effect of MKK3/6 overexpression on basal p38, JNK2 and p44/42 phosphorylation.

RIN-5AH cells were transfected, sorted and lysed for immunoblotting as described in the legend to Figure 5. Samples were probed with phospho-specific antibodies recognizing phosphorylated p38-MAPK, JNK2 and p44/42-ERK. Non-phospho-specific ERK antibody was used to visualize total p44/p42 levels. The immunoblot is representative of four experiments.

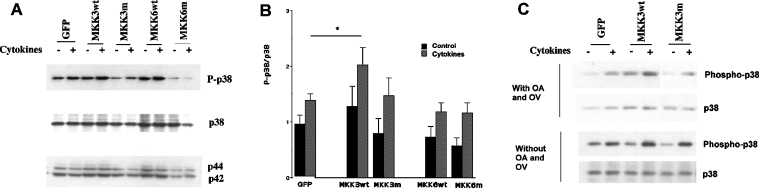

Effect of transient MKK3/6 overexpression on cytokine-induced p38 phosphorylation and cell death

Having demonstrated that transient MKK3 overexpression resulted in increased p38 phoshorylation, we next investigated the effect of MKK3/6 overexpression on cytokine-induced p38 phosphorylation. Also, cytokine-stimulated p38 phosphorylation was modestly augmented by MKK3wt overexpression, whereas MKK6wt expression was without effect (Figures 7A and 7B). Again, expression of MKK3m and MKK6m did not affect p38 phosphorylation (Figures 7A and 7B). The different MKK3/6 constructs were without effect on JNK2 or p42/p44 phosphorylation levels (results not shown). Previous studies have demonstrated that p38 and JNK phosphorylation is counteracted by MAPK-activated phosphatases [33]. Thus the rather modest increase in p38 phosphorylation, in response to cytokines and MKK3wt (Figure 7A), may have resulted from increased p38 dephosphorylation. To investigate this, RIN-5AH cell clones were preincubated with the phosphatase inhibitors okadaic acid and orthovanadate for 10 min before stimulation with cytokines. In these experiments, both basal and cytokine-stimulated p38 phosphorylation was more pronounced in the presence than in the absence of phosphatase inhibitors (Figure 7C).

Figure 7. Effects of transient MKK3/6 overexpression on cytokine-stimulated p38 phosphorylation.

(A) Immunoblot showing p38 phosphorylation in response to IL-1β (50 units/ml) and IFN-γ (1000 units/ml) and MKK3/6 overexpression. Two days after transfection and 1 day after FACS, the cells were exposed to the cytokines for 30 min, lysed, separated by SDS gel electrophoresis and analysed by immunoblotting with indicated antibodies. Untreated cells were used as control. (B) Results from immunoblots as the one shown in (A) were quantified by densitometry. Values of phospho-protein bands were related to those of non-phospho-specific protein bands. Results shown are means±S.E.M. for eight independent experiments. *P<0.05 using ANOVA and Student–Newman–Keuls post-ANOVA test. (C) Effects of okadaic acid (OA) and sodium orthovanadate (OV) on cytokine- and MKK3-stimulated p38 phosphorylation. Two days after transfection and 1 day after FACS, cells were pretreated with OA (100 nM) and OV (100 μM) for 10 min. After pretreatment, some groups of cells were exposed to the cytokines IL-β (50 units/ml) and IFN-γ (1000 units/ml) for 30 min. Cells were then lysed and cell proteins were separated by SDS gel electrophoresis and analysed by immunoblotting with p38 and phospho-specific p38 antibodies. The Figure is representative of three observations.

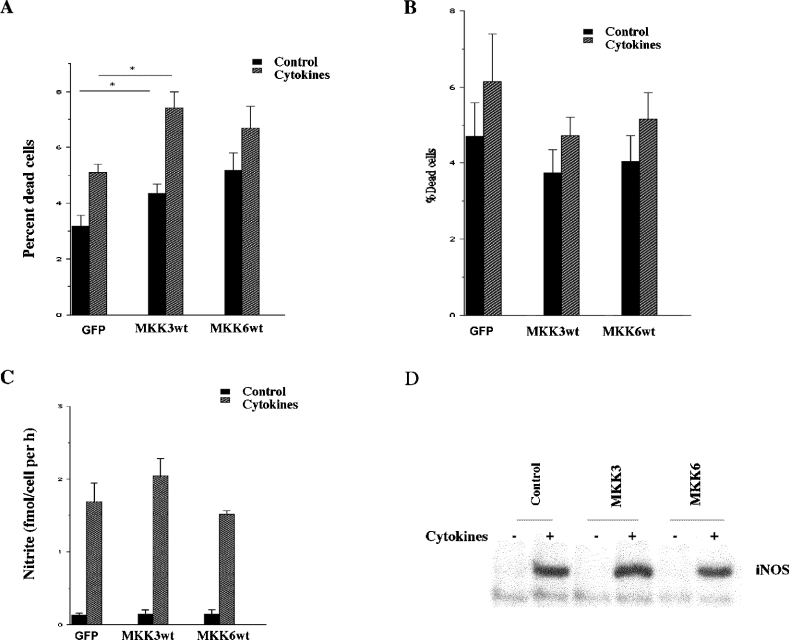

To establish whether the MKK3-augmented p38 phosphorylation affects cell death rates, the transiently transfected RIN-5AH cells were exposed to cytokines for 24 h and propidium uptake was assessed by flow cytometry. We observed that both basal and cytokine-induced cell death rates were increased in MKK3wt cells (Figure 8A). There was also a trend to higher cell death rates in the MKK6wt-transfected cells, but it did not reach statistical significance. To analyse whether nitric oxide-independent cell death is affected by MKK3/6, we exposed the transfected cells to L-NMMA and cytokines for 3 days. These experiments revealed a small increase in cell death rates in response to cytokines, which, however, was not altered by MKK3/6 overexpression (Figure 8B). Also, cytokine-induced iNOS expression and nitric oxide production were unaffected by MKK3/6 (Figures 8C and 8D), which indicates that MKK3-induced p38 activation enhances RIN-5AH cell sensitivity to nitric oxide.

Figure 8. Effect of MKK3/6 overexpression on cytokine-induced apoptosis, nitric oxide production and iNOS levels in transiently transfected cells.

(A) Two days after transfection and 1 day after FACS, RIN-5AH cells were exposed to the cytokines IL-β (50 units/ml) and IFN-γ (1000 units/ml) for 24 h. Cells were then stained with propidium iodide and cell viability was assessed using the FACSCalibur flow cytometer. Results are presented as percentage dead cells of the total cell count. Results are means±S.E.M. for six independent experiments. *P<0.05 using ANOVA and Dunnet's post-ANOVA test. (B) Two days after transfection and 1 day after FACS, L-NMMA (2 mM) was added to all the groups of cells and, at the same time, IL-1β (50 units/ml), IFN-γ (1000 units/ml) and TNF-α (1000 units/ml) (cytokines) were added to some groups. Cells were incubated for 72 h and cell viability was assessed using flow cytometry. Results are presented as percentage dead cells of total cell count and are the means±S.E.M. for five independent experiments. (C, D) Two days after transfection and 1 day after FACS, cells were exposed to the cytokines IL-1β (50 units/ml) and IFN-γ (1000 units/ml). Samples were collected the day after addition of cytokines and the levels of nitrite were measured spectrophotometrically (C). Results shown are means±S.E.M. for six independent experiments. Cells were also exposed to the combination of IL-1β (50 units/ml) and IFN-γ (1000 units/ml) for 6 h, lysed, separated on the SDS gel and analysed for iNOS expression by immunoblotting (D).

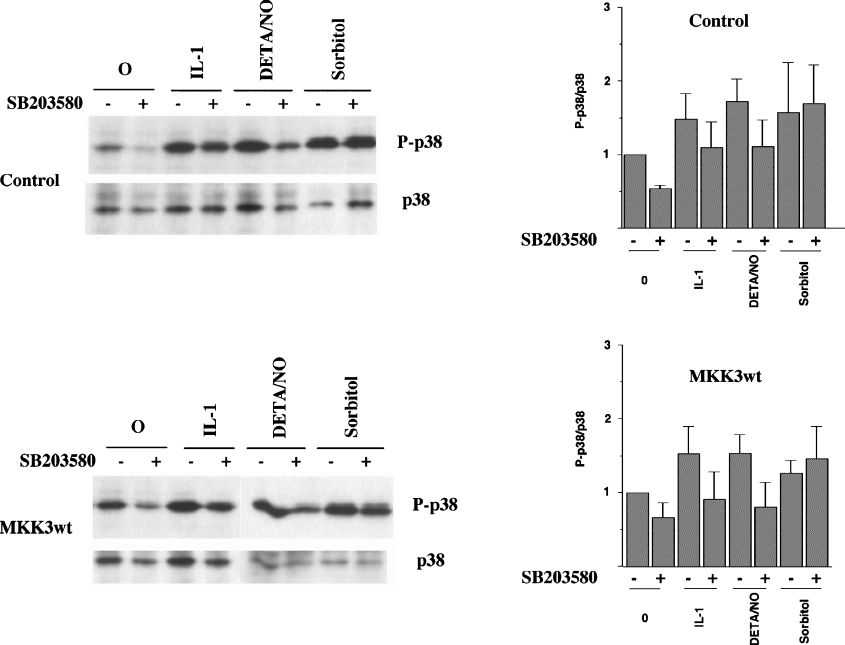

MKK3 does not affect p38 autophosphorylation

Recent investigations have demonstrated an MKK3-independent and TAB1-dependent mechanism that leads to p38 autophosphorylation [14]. As MKK3/6m expression did not prevent cytokine-induced p38 phosphorylation, we analysed the putative role of MKK3 in IL-1β-, DETA/NONOate- and sorbitol-induced p38 autophosphorylation. P38 autophosphorylation at amino acids 180 and 182 is inhibited by SB203580. This is a pyridinyl imidazole compound that, by binding to the ATP-binding site, selectively inhibits the α- and β-isoforms of p38 [34]. Interestingly, both basal and IL-1β- and DETA/NONOate-induced p38 phosphorylation was partially counteracted by 10 μM SB203580 (Figure 9). Hyperphosphorylation of p38 in response to osmotic stress, induced by sorbitol, was, however, not affected by SB203580 (Figure 9), indicating that the sorbitol pathway does not involve increased p38 autophosphorylation. Neither MKK3wt nor MKK3m affected SB203580-induced inhibition of p38 phosphorylation (Figure 9). These results indicate that IL-1β- and DETA/NONOate-induced p38 activation require an MKK3-independent p38 autophosphorylation step, whereas the sorbitol pathway does not.

Figure 9. MKK3 does not affect p38 autophosphorylation in response to IL-1β, DETA/NONOate and sorbitol.

Two days after transfection and 1 day after FACS, cells were pretreated with SB203580 (10 μM) for 30 min and then stimulated with IL-1β (50 units/ml), DETA/NONOate (2.5 mM; DETA/NO) and sorbitol (0.4 M) for 30 min. Cells were lysed, separated by SDS gel electrophoresis and analysed by immunoblotting with p38 and phospho-specific p38 antibodies. The Figure is representative of three independent experiments.

DISCUSSION

We report in the present paper that the proinflammatory cytokine IL-1β and the nitric oxide donor DETA/NONOate both activate the p38 MAPK, that MKK3-induced p38 phosphorylation augments cytokine-induced cell death and that knockdown of p38α in human islet cells decreases the sensitivity to nitric oxide. To our knowledge, this is the first time the genetic gain and loss of function approach has been utilized to elucidate the role of p38 in cytokine-induced β-cell death. Because cytokines induce cell death, at least in rodent β-cells, mainly by inducing iNOS and production of nitric oxide [35,36], our results clearly support a direct role of p38 in cytokine-induced rodent β-cell death. Indeed, recent studies have shown that pharmacological inhibition of p38 prevents the spontaneous development of diabetes that occurs in NOD (non-obese diabetic) mouse [37]. Thus it is likely that after the initial cytokine-receptor-induced p38 activation, an event that is nitric oxide-independent, iNOS induction and persistently high levels of nitric oxide maintain p38 in a hyperphosphorylated state, which drives the insulin-producing cell to apoptosis/necrosis. It is, however, not clear which downstream targets of p38 convey the proapoptotic effect. In insulin-producing cells, p38 is known to promote phosphorylation of hsp25, MAPKAP-K2, MSK1, ATF2 and CREB [8,9], to control caspase-3 activity [38] and to increase expression of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines [39,40], but the importance of these events in β-cell apoptosis is unknown. Alternatively, p38 inhibition might promote survival by increasing Bcl-XL levels as we presently observed a partial restoration of Bcl-XL levels after exposure to NO.

It has also been suggested that p38 participates in cytokine-induced iNOS expression thereby aggravating nitric oxide-induced β-cell damage [8,41–43]. P38-mediated stimulation of iNOS-gene transcription might involve activation of the transcription factors NF-κB, C/EBP (CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein) and ATF2 [44]. This possibility is not contradicted by the findings of the present study, as there was a non-significant trend to a higher nitric oxide production in MKK3-overexpressing cells. In addition, a stimulatory effect of p38 on the transcription of the iNOS gene might not be easily detected in cells that are incubated in the presence of high concentrations of both IL-1β and IFN-γ. Such a pronounced stimulation may generate a maximal response, which cannot be further modulated by p38.

The role of nitric oxide-induced p38 activation in cytokine-induced β-cell death is less clear in human islet cells than in rodent cells. Although the combination of IL-1β and IFN-γ is known to induce iNOS and nitric oxide production also in human islets [45], inhibitors of nitric oxide synthesis do not prevent cytokine-induced cell death in vitro [30]. Thus it is not clear whether the presently observed p38-mediated increase in sensitivity to nitric oxide is pertinent to cytokine-induced β-cell death in human Type I diabetes. In addition, as MKK3-mediated p38 activation did not affect cell death rates in the presence of a NOS (nitric oxide synthase)-inhibitor, it is not likely that nitric oxide-independent pathways that lead to apoptosis require p38 activity.

Although previous reports provide support for a role of p38 in cytokine-induced β-cell death [8,9,41,44], some studies do not [7,46]. This inconsistency in the literature might have resulted from the complex and potent p38 counter-regulatory mechanisms that are activated in response to p38 phosphorylation [47,48]. In a previous publication, we observed that p38 inhibition resulted in the activation of JNK2 [43], indicating that p38 activates a phosphatase that dephosphorylates JNK2. Similarly, inhibition of JNK has been reported to enhance p38-mediated CREB phosphorylation [49], supporting the notion that p38 is also dephosphorylated by a MAPK-activated phosphatase. In the present study, not only did inhibitors of phosphatases enhance p38 phosphorylation, but also the protein levels of p38, JNK and p42 were decreased in response to a long-term MAPK activation. This is in line with a recent paper [50], in which it was demonstrated that sorbitol downregulated ERK1/ERK2 in NIH3T3 cells by inducing ERK ubiquitination and proteasome-mediated degradation. The combined effect of the presently observed counter-regulatory mechanisms did not result in an augmented RIN-5AH cell death in response to cytokines. Thus prolonged pharmacological inhibition of p38 probably promotes MAPK gene up-regulation and increased phosphorylation of JNK and ERK, which can easily generate effects that confound the direct consequences of p38 inhibition.

The pathways that lead to p38 activation are rapidly becoming increasingly complex. Not only are the different p38 isoforms differentially activated [51], leading to opposite transcription factor activation outcomes [52], but also the signals induced by different p38 activators, such as arsenite, osmotic chock, cytokines, growth factors, reactive oxygen species and nitric oxide, seem to vary. The classic p38-activating pathway consists of a cascade in which a MAP3K, such as TAK1 [53] or ASK1 [54], phosphorylates the MAP2Ks MKK3 and MKK6, which in turn phosphorylate p38. p38 is also activated in response to growth factors by a Ras/Ral/Src pathway, which might not require MKK3/6 [17]. Alternatively, p38 activation is achieved by Tab1-mediated p38 autophosphorylation [14]. In support of the latter alternative, we report in the present paper that the p38 inhibitor SB203580 inhibited cytokine- and nitric oxide-induced p38 phosphorylation. Moreover, as overexpression of MKK3 did not affect cytokine- or nitric oxide-induced p38 phosphorylation, we propose that β-cell activation of p38 in response to these stress-inducing agents does not require MKK3/6 phosphorylating activity. On the other hand, activation of p38 by sorbitol was not inhibited by SB203580, indicating that osmotic stress-induced p38 activation may occur via the MKK3/6-dependent pathway. This hypothesis, however, requires further experimentation to be verified.

Although the currently used MKK3/6 mutants do not phosphorylate p38 [55] and therefore also compete with endogenous MKK3/6 phosphorylation activity, we cannot exclude the possibility that the mutants mediate MKK3/6 phosphorylation-independent effects. For example, we observed that the MKK3 mutant, in a similar manner to wild-type MKK3, in some experiments decreased p42 levels. This might indicate that MKK3, by merely binding to a substrate, promotes ERK degradation.

Several publications have demonstrated that p38 activation and subsequent apoptosis lie downstream of specific PKC isoforms. For example, hyperglycaemia activates p38 in smooth muscle cells via PKCδ [56] and androgens activate p38 via both PKCα and PKCδ in prostate cancer cells [16]. To investigate this, we down-regulated PKCδ using RNAi. In these knockdown experiments, however, nitric oxide-induced human islet cell death was not affected, indicating that the PKCδ isoform is not mediating p38-induced sensitivity to nitric oxide.

In summary, our results support a role of p38 in cytokine-induced β-cell death. p38 activation in response to cytokine-induced nitric oxide production may not require MKK3/6-induced phosphorylation. A better understanding of the cytokineinduced events that lead to p38 activation and β-cell apoptosis will hopefully improve our understanding of the pathogenesis of Type I diabetes.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by Swedish Medical Research Council grants (72P-12995, 12X-11564 and 12X-109), the Swedish Diabetes Association, the Family Ernfors Fund and the European Foundation for the Study of Diabetes.

References

- 1.Bendtzen K., Mandrup-Poulsen T., Nerup J., Nielsen J. H., Dinarello C. A., Svenson M. Cytotoxicity of human pI 7 interleukin-1 for pancreatic islets of Langerhans. Science. 1986;232:1545–1547. doi: 10.1126/science.3086977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eizirik D. L., Mandrup-Poulsen T. A choice of death – the signal-transduction of immune-mediated beta-cell apoptosis. Diabetologia. 2001;44:2115–2133. doi: 10.1007/s001250100021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Welsh N., Eizirik D. L., Bendtzen K., Sandler S. Interleukin-1 beta-induced nitric oxide production in isolated rat pancreatic islets requires gene transcription and may lead to inhibition of the Krebs cycle enzyme aconitase. Endocrinology. 1991;129:3167–3173. doi: 10.1210/endo-129-6-3167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barbu A., Welsh N., Saldeen J. Cytokine-induced apoptosis and necrosis are preceded by disruption of the mitochondrial membrane potential (Deltapsi(m)) in pancreatic RINm5F cells: prevention by Bcl-2. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2002;190:75–82. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(02)00009-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oyadomari S., Takeda K., Takiguchi M., Gotoh T., Matsumoto M., Wada I., Akira S., Araki E., Mori M. Nitric oxide-induced apoptosis in pancreatic beta cells is mediated by the endoplasmic reticulum stress pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2001;98:10845–10850. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191207498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saldeen J., Tillmar L., Karlsson E., Welsh N. Nicotinamide- and caspase-mediated inhibition of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase are associated with p53-independent cell cycle (G2) arrest and apoptosis. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2003;243:113–122. doi: 10.1023/a:1021651811345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pavlovic D., Andersen N. A., Mandrup-Poulsen T., Eizirik D. L. Activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK)1/2 contributes to cytokine-induced apoptosis in purified rat pancreatic beta-cells. Eur. Cytokine Netw. 2000;11:267–274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Larsen C. M., Wadt K. A., Juhl L. F., Andersen H. U., Karlsen A. E., Su M. S., Seedorf K., Shapiro L., Dinarello C. A., Mandrup-Poulsen T. Interleukin-1beta-induced rat pancreatic islet nitric oxide synthesis requires both the p38 and extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 mitogen-activated protein kinases. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:15294–15300. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.24.15294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saldeen J., Lee J. C., Welsh N. Role of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (p38 MAPK) in cytokine-induced rat islet cell apoptosis. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2001;61:1561–1569. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(01)00605-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Keesler G. A., Bray J., Hunt J., Johnson D. A., Gleason T., Yao Z., Wang S. W., Parker C., Yamane H., Cole C., et al. Purification and activation of recombinant p38 isoforms alpha, beta, gamma, and delta. Protein Expr. Purif. 1998;14:221–228. doi: 10.1006/prep.1998.0947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Enslen H., Brancho D. M., Davis R. J. Molecular determinants that mediate selective activation of p38 MAP kinase isoforms. EMBO J. 2000;19:1301–1311. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.6.1301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kumar S., McDonnell P. C., Gum R. J., Hand A. T., Lee J. C., Young P. R. Novel homologues of CSBP/p38 MAP kinase: activation, substrate specificity and sensitivity to inhibition by pyridinyl imidazoles. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1997;235:533–538. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnson G. L., Lapadat R. Mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways mediated by ERK, JNK, and p38 protein kinases. Science. 2002;298:1911–1912. doi: 10.1126/science.1072682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ge B., Gram H., Di Padova F., Huang B., New L., Ulevitch R. J., Luo Y., Han J. MAPKK-independent activation of p38alpha mediated by TAB1-dependent autophosphorylation of p38alpha. Science. 2002;295:1291–1294. doi: 10.1126/science.1067289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Norman K. L., Hirasawa K., Yang A. D., Shields M. A., Lee P. W. Reovirus oncolysis: the Ras/RalGEF/p38 pathway dictates host cell permissiveness to reovirus infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2004;101:11099–11104. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404310101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tanaka Y., Gavrielides M. V., Mitsuuchi Y., Fujii T., Kazanietz M. G. Protein kinase C promotes apoptosis in LNCaP prostate cancer cells through activation of p38 MAPK and inhibition of the Akt survival pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:33753–33762. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303313200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ouwens D. M., de Ruiter N. D., van der Zon G. C., Carter A. P., Schouten J., van der Burgt C., Kooistra K., Bos J. L., Maassen J. A., van Dam H. Growth factors can activate ATF2 via a two-step mechanism: phosphorylation of Thr71 through the Ras-MEK-ERK pathway and of Thr69 through RalGDS-Src-p38. EMBO J. 2002;21:3782–3793. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xia Z., Dickens M., Raingeaud J., Davis R. J., Greenberg M. E. Opposing effects of ERK and JNK-p38 MAP kinases on apoptosis. Science. 1995;270:1326–1331. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5240.1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Perfettini J. L., Castedo M., Nardacci R., Ciccosanti F., Boya P., Roumier T., Larochette N., Piacentini M., Kroemer G. Essential role of p53 phosphorylation by p38 MAPK in apoptosis induction by the HIV-1 envelope. J. Exp. Med. 2005;201:279–289. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schulze-Osthoff K., Ferrari D., Riehemann K., Wesselborg S. Regulation of NF-kappa B activation by MAP kinase cascades. Immunobiology. 1997;198:35–49. doi: 10.1016/s0171-2985(97)80025-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Basu A. Involvement of protein kinase C-delta in DNA damage-induced apoptosis. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2003;7:341–350. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2003.tb00237.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shi Y. Mechanisms of caspase activation and inhibition during apoptosis. Mol. Cell. 2002;9:459–470. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00482-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hsu S. C., Gavrilin M. A., Tsai M. H., Han J., Lai M. Z. p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase is involved in Fas ligand expression. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:25769–25776. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.36.25769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Da Silva J., Pierrat B., Mary J. L., Lesslauer W. Blockade of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway inhibits inducible nitric-oxide synthase expression in mouse astrocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:28373–28380. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.45.28373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matsumoto T., Turesson I., Book M., Gerwins P., Claesson-Welsh L. p38 MAP kinase negatively regulates endothelial cell survival, proliferation, and differentiation in FGF-2-stimulated angiogenesis. J. Cell Biol. 2002;156:149–160. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200103096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hägerkvist R., Mokhtari D., Myers J. W., Tengholm A., Welsh N. SiRNA produced by recombinant dicer mediates efficient gene silencing in islet cells. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2005;1040:114–122. doi: 10.1196/annals.1327.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Myers J. W., Ferrell J. E. Silencing gene expression with dicer-generated siRNA pools. Methods Mol. Biol. 2005;309:93–196. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-935-4:093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Welsh N., Makeeva N., Welsh M. Overexpression of the Shb SH2 domain-protein in insulin-producing cells leads to altered signaling through the IRS-1 and IRS-2 proteins. Mol. Med. 2002;8:695–704. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Welsh N. Assessment of apoptosis and necrosis in isolated islets of Langerhans: methodological considerations and improvements. Curr. Top. Biochem. Res. 2000;3:189–200. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eizirik D. L., Sandler S., Welsh N., Cetkovic-Cvrlje M., Nieman A., Geller D. A., Pipeleers D. G., Bendtzen K., Hellerstrom C. Cytokines suppress human islet function irrespective of their effects on nitric oxide generation. J. Clin. Invest. 1994;93:1968–1974. doi: 10.1172/JCI117188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Welsh N. Interleukin-1 beta-induced ceramide and diacylglycerol generation may lead to activation of the c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase and the transcription factor ATF2 in the insulin-producing cell line RINm5F. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:8307–8312. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.14.8307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu D., Pavlovic D., Chen M. C., Flodstrom M., Sandler S., Eizirik D. L. Cytokines induce apoptosis in beta-cells isolated from mice lacking the inducible isoform of nitric oxide synthase (iNOS–/–) Diabetes. 2000;49:1116–1122. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.49.7.1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lai K., Wang H., Lee W. S., Jain M. K., Lee M. E., Haber E. Mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase-1 in rat arterial smooth muscle cell proliferation. J. Clin. Invest. 1996;98:1560–1567. doi: 10.1172/JCI118949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lisnock J., Tebben A., Frantz B., O'Neill E. A., Croft G., O'Keefe S. J., Li B., Hacker C., de Laszlo S., Smith A., et al. Molecular basis for p38 protein kinase inhibitor specificity. Biochemistry. 1998;37:16573–16581. doi: 10.1021/bi981591x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Eizirik D. L., Flodstrom M., Karlsen A. E., Welsh N. The harmony of the spheres: inducible nitric oxide synthase and related genes in pancreatic beta cells. Diabetologia. 1996;39:875–890. doi: 10.1007/BF00403906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Southern C., Schulster D., Green I. C. Inhibition of insulin secretion by interleukin-1 beta and tumour necrosis factor-alpha via an L-arginine-dependent nitric oxide generating mechanism. FEBS Lett. 1990;276:42–44. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)80502-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ando H., Kurita S., Takamura T. The specific p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway inhibitor FR167653 keeps insulitis benign in nonobese diabetic mice. Life Sci. 2004;74:1817–1827. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2003.09.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ehses J. A., Casilla V. R., Doty T., Pospisilik J. A., Winter K. D., Demuth H.-U., Pederson R. A., McIntosh H. S. Glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide promotes beta-(INS-1) cell survival via cyclic adenosine monophosphate-mediated caspase-3 inhibition and regulation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase. Endocrinology. 2003;144:4433–4445. doi: 10.1210/en.2002-0068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Matsuda T., Omori K., Vuong T., Pascual M., Valiente L., Ferreri K., Todorov I., Kuroda Y., Smith C. V., Kandeel F., et al. Inhibition of p38 pathway suppresses human islet production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and improves islet graft function. Am. J. Transplant. 2005;5:484–493. doi: 10.1046/j.1600-6143.2004.00716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen M. C., Proost P., Gysemans C., Mathieu C., Eizrik D. L. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 is expressed in pancreatic islets from prediabetic NOD mice and in interleukin-1 beta-exposed human and rat islet cells. Diabetologia. 2001;44:325–332. doi: 10.1007/s001250051622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sprinkel A. M., Andersen N. A., Mandrup-Poulsen T. Glucose potentiates interleukin-1 beta (IL-1 beta)-induced p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase activity in rat pancreatic islets of Langerhans. Eur. Cytokine Netw. 2001;12:331–333. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chong M. M., Thomas H. E., Kay T. W. gamma-Interferon signaling in pancreatic beta-cells is persistent but can be terminated by overexpression of suppressor of cytokine signaling-1. Diabetes. 2001;50:2744–2751. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.12.2744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Saldeen J., Welsh N. p38 MAPK inhibits JNK2 and mediates cytokine-activated iNOS induction and apoptosis independently of NF-KB translocation in insulin-producing cells. Eur. Cytokine Netw. 2004;15:47–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bhat N. R., Feinstein D., Shen Q., Bhat A. p38 MAPK-mediated transcriptional activation of inducible nitric-oxide synthase in glial cells. Roles of nuclear factors, nuclear factor kappa B, cAMP response element-binding protein, CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein-beta, and activating transcription factor-2. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:29584–29592. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204994200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Eizirik D. L., Pipeleers D. G., Ling Z., Welsh N., Hellerstrom C., Andersson A. Major species differences between humans and rodents in the susceptibility to pancreatic beta-cell injury. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1994;91:9253–9256. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.20.9253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ammendrup A., Mailllard A., Nielsen K., Andersen N. A., Serup P., Madsen O. D., Mandrup-Poulsen T., Bonny C. The c-Jun amino-terminal kinase pathway is preferentially activated by interleukin-1 and controls apoptosis in differentiating pancreatic beta-cells. Diabetes. 2000;49:1468–1476. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.49.9.1468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Westermarck J., Li S. P., Kallunki T., Han J., Kahari V. M. p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase-dependent activation of protein phosphatases 1 and 2A inhibits MEK1 and MEK2 activity and collagenase 1 (MMP-1) gene expression. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2001;21:2373–2383. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.7.2373-2383.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang H., Shi X., Hampong L. B., Blanis L., Pelech S. Stress-induced inhibition of ERK1 and ERK2 by direct interaction with p38 MAP kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:6905–6908. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C000917200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vaishnav D., Jambal P., Reusch J. E., Pugazhenthi S. SP600125, an inhibitor of c-jun N-terminal kinase, activates CREB by a p38 MAPK-mediated pathway. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2003;307:855–860. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)01287-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lu Z., Xu S., Joazeiro C., Cobb M. H., Hunter T. The PHD domain of MEKK1 acts as an E3 ubiquitin ligase and mediates ubiquitination and degradation of ERK1/2. Mol. Cell. 2002;9:945–956. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00519-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Alonso G., Ambrosino C., Jones M., Nebreda A. Differential activation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase isoforms depending on signal strength. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:40641–40648. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007835200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pramanik R., Qi X., Borowicz S., Choubey D., Schultz R. M., Han J., Chen G. p38 isoforms have opposite effects on AP-1-dependent transcription through regulation of c-Jun. The determinant roles of the isoforms in the p38 MAPK signal specificity. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:4831–4839. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207732200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jiang Z., Ninomiya-Tsuji J., Qian Y., Matsumoto K., Li X. Interleukin-1 (IL-1) receptor-associated kinase-dependent IL-1-induced signaling complexes phosphorylate TAK1 and TAB2 at the plasma membrane and activate TAK1 in the cytosol. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2002;22:7158–7167. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.20.7158-7167.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Li X., Zhang R., Luo D., Park S. L., Wang Q., Kim Y., Min W. Tumor necrosis factor alpha-induced desumoylation and cytoplasmic translocation of homeodomain-interacting protein kinase 1 are critical for apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1-JNK/p38 activation. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:15061–15070. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M414262200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Raingeaud J., Whitmarsh A. J., Barrett T., Derijard B., Davis R. J. MKK3- and MKK6-regulated gene expression is mediated by the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase signal transduction pathway. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1996;16:1247–1255. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.3.1247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Igarashi M., Wakasaki H., Takahara N., Ishii H., Jiang Z. Y., Yamauchi T., Kuboki K., Meier M., Rhodes C., King G. Glucose or diabetes activates p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase via different pathways. J. Clin. Invest. 1999;103:185–195. doi: 10.1172/JCI3326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]