INTRODUCTION

Public health has come under criticism in recent times in some quarters, charged with failing to tackle important health problems over the last 30 years in the UK. This criticism has come most notably from Derek Wanless in his influential report, Securing Good Health for the Whole Population.1 He alleges for example that `the major drivers of public health have been recognized since the 1970s, with numerous “upstream” and “downstream” public health strategies having been proposed. However, 30 years on, despite some successes, implementation has been partial at best'. Other critics allege that `public health has made no significant contribution to policy since the Ottawa Charter' (personal communication, T Jewell). Currently, the re-organization of Primary Care Trusts and Strategic Health Authorities in England once again threatens to destabilize existing public health teams in England, only a few years after the upheavals of the implementation of `Shifting the Balance of Power' initiative.

However, despite the organizational turmoil that has been facing public health in recent years, we would challenge the view that public health in the UK has not had considerable success to date. Evidence to support this view, and reasons for some of the failures will be discussed.

PUBLIC HEALTH ACHIEVEMENTS OF THE TWENTIETH CENTURY

The Centre for Communicable Disease Control in Atlanta, USA has published a list of 10 great public health achievements from 1900-1999.2,3 These are summarized in Box 1. These are all applicable to the UK, and demonstrate the wide range of improvements in public health that we perhaps take for granted. They have made a significant contribution to the major and sustained increases in life expectancy in the UK to 76 years for men and 81 years for women, from 45 and 49 years, respectively, at the turn of the century.4

DOMAINS OF PUBLIC HEALTH PRACTICE

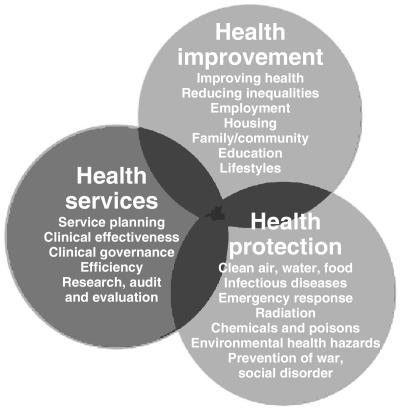

Public health has been defined as `the science and art of preventing disease, prolonging life and preventing disability through the organized efforts of society'.5 One way of considering public practice is to use the framework of three domains recognized by the Faculty of Public Health, namely health improvement, health protection and service improvement (Figure 1). In each of these areas, public health specialists and practitioners need to work in partnership with others, highlighting and analysing the important determinants of health, identifying effective interventions, and working with others to influence, persuade and ensure both the implementation of effective interventions and a shift in the underlying determinants of health.

Figure 1.

Areas of public health practice

In this complex world, it is difficult to directly attribute success to one professional group or other—many players are required at all levels. However, effective public health action is underpinned by analysis of population health problems and possible interventions, followed by action to secure effective implementation. This not only requires analysis, but advocacy and vigorous and persuasive argument, in all areas where public health professionals play a significant role.

Examples of `success' stories will be provided in each of these three domains of public health practice.

HEALTH PROTECTION

Clean air, pure water and safe food are all taken for granted in developed countries. Food poisoning rates have declined by 18% in the UK over the last 4 years.6 There have been significant improvements in childhood infections, with the childhood immunisation programme in the UK virtually eradicating polio and diphtheria in this country. Following concerns about the pertussis vaccine in the late 1970s, vaccination rates are now stable, and whooping cough rates have again fallen. The introduction of the Measles Mumps and Rubella Vaccine in 1988, Haemophilus B vaccine and meningitis C vaccine have each led to a dramatic decline in the incidence of these common diseases; the recent epidemic of mumps only serves to demonstrate the effectiveness of the programme. The introduction of influenzae vaccination for those over 65 years of age and other vulnerable groups is another success. Public health professionals have been pivotal in making the case for these programmes and actively involved in the subsequent implementation of these policies.

Box 1 Ten great public health achievements (after Centre for Communicable Disease Control, Atlanta)

Vaccination—the eradication of smallpox; elimination of polio (in the Americas); and control of measles, rubella, tetanus, diphtheria, and Hemophilus influenzae type b

Motor-vehicle safety—reduction in motor vehicle-related deaths due to engineering improvements in vehicles and highways and change in personal behaviours (use of safety device and reduction in drinking and driving)

Safer workplaces—control of pneumoconiosis and silicosis; reduction in fatal occupational injuries

Control of infectious diseases—control of typhoid and cholera through improved water and sanitation; and of tuberculosis and sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) by antibiotics

Decline in deaths from coronary heart disease and stroke—from risk-factor modification (especially smoking cessation and blood pressure control) and improved access to early detection and treatment

Safer and healthier foods—decrease in microbial contamination and increase in nutritional content; nutritional deficiency diseases (rickets, goitre, pellagra) almost eliminated

Healthier mothers and babies—from better hygiene and nutrition, availability of antibiotics, access to healthcare and technological advances in neonatal and maternal medicine

Family planning—altered socioeconomic role of women, reduced family size, increased birth intervals, and improved maternal and child health; barrier contraceptives also reduced unwanted pregnancies and transmission of STDs

Fluoridation of drinking water—resulted in reductions in tooth decay and tooth loss

Recognition of tobacco use as a health hazard—resulted in changes in social norms, reduced prevalence of smoking and mortality from smoking-related diseases.

The AIDS epidemic in the 1980s led to the innovative use of the mass media in health promotion on a unique scale in this country. This scale of the campaign was unprecedented in the sphere of public health. This campaign and other active work in the field of HIV prevention in intravenous drug users have helped keep rates of infection in the UK in this group relatively low compared to a number of other European countries.7

One highly effective piece of public health legislation has been that relating to seat belts. The introduction of this piece of legislation in 1983 lead to a 15% reduction in patients brought to hospital, a 25% reduction in those requiring admissions to wards, and a similar fall in bed-occupancy. There were fewer patients with severe injuries after legislation, and a reduction in face, eye, brain and lung injuries.8 A key public health role was the education, advocacy and lobbying required in advance of the legislation to ensure its acceptability and subsequent implementation. Deaths from road traffic injuries have continued to fall in Great Britain, with a fall from 4229 in 1992 to 3431 in 2002, and a decline of over 50% in the number of child pedestrians killed from 180 in 1992 to 79 in 2002.9

Another area of public health success has been the continued and sustained reduction in suicide rates throughout the population. Although young men have been a key risk group, there is evidence that even in this age group rates are finally falling from its peak in 1998 to its lowest level for almost 20 years.10 The introduction of restrictions on sales of paracetamol and the use of blister packaging, which has been associated with reductions in admissions to hospital and deaths from paracetamol poisoning, and a decline in liver transplants from paracetamol poisoning.11

HEALTH IMPROVEMENT

Researchers in the UK have led understanding internationally about the importance of the role of social determinants and inequalities in health.12,13

There has been a remarkable decline in deaths from acute myocardial infarction and stroke over the last 30 years. It is estimated that 42% of this decline has been due to improved medical and surgical treatments and 58% due to the change in risk factors, mostly smoking.14 Looking at nutrition, long-term, some aspects of the national diet have significantly improved. Between 1975 and 2002/2003 fresh and processed fruit consumption rose; vegetable consumption remained static, and milk, egg and fat consumption declined by almost 40%.15 There can be little doubt that public health efforts have contributed significantly to both risk factor changes and improvements in equitable access to effective treatment.

Public health activity has been intense in the field of tobacco control since the 1960s, and the publication of the landmark Smoking Kills White Paper in 1998 was followed by restrictions on promotion and advertizing in 2002. Disappointingly, the government did not back a full ban on workplace restrictions in the recent Choosing Health White Paper, and this is an area of ongoing concern. However, smoking prevalence has declined dramatically over the last 25 years, and in professional groups is now well under 20%. Smoking rates in teenage children aged 11-15 years peaked in 1996 and have since fallen to an all time low of 7% in boys and 11% in girls.16

SERVICE IMPROVEMENT

Public health professionals in the UK have been heavily involved and prominent members of key initiatives which have developed systematic evidence-based approaches to the equitable delivery of high quality healthcare in the UK, including the evidence-based medicine movement; the Cochrane Collaboration (named after a founding fellow of the Faculty of Public Health); the development of guidelines for cancer care; the establishment of the National Institute for Clinical Excellence, and the development and implementation of National Service Frameworks. These are beginning to show an impact on population health; with for example, increases in cancer survival rates,17 and decreases in deaths from asthma of 40% for those under 65 years from 1979 to 1999.18

One example of a dramatic success is the reduction in breast cancer deaths. Although mortality rates from breast cancer had been increasing steadily ever since the 1960s, in the late 1980s, they flattened out, and then during the 1990s decreased substantially18 and have continued to fall since then. The introduction of a national screening programme, early surgery and the wider use of tamoxifen and other adjuvant therapy have all played a part, although the relative contribution of each is intensely debated. Public health professionals have been influential in implementing screening programmes, evaluating interventions and promoting equity of access to high quality treatment.

PUBLIC HEALTH `FAILURES' AND FUTURE CHALLENGES

However, despite these areas of success there are other areas where public health has made less progress. Although life expectancy is rising in all social groups and across all geographical areas in the UK, stark differences remain and may be worsening.20 It is estimated that over half of these differences are attributable to current and historical patterns of tobacco consumption.21 There are significant concerns about increasing levels of alcohol consumption, particularly in young women, with substantial rises in deaths from chronic liver disease and cirrhosis. This is in stark contrast with our European neighbours where rates are falling.22 Other areas of concern include nutrition, (particularly rising rates of childhood obesity), a rising incidence of sexually transmitted diseases and an increasing burden of chronic disease in the elderly.

Are public health professionals entirely to blame for these failures? Wanless recognized the need for a plurality of approaches to be used to pursue public health goals, including legitimate tasks for government such as:

the use of taxes.

subsidies such as public spending or tax credits

voluntary agreements

disseminating public health information.

The pioneering international World Health Organization Global Framework on Tobacco Control23 which adopted an evidence-based approach to evaluating potential interventions, considered education, legislation, regulation and litigation as possible interventions and tools in the field of tobacco control.

Is it possible that in some cases, where public health indices are worsening, it is because of an over-reliance on a public health approach based primarily on education and personal choice, (an approach heavily promoted by Wanless1) and a failure to consider, or implement, other pivotal public health strategies such as regulation and fiscal intervention? Perhaps the public health failure has not been in failing to diagnose and identifying the problems, but in failing to build the effective coalitions and public support required to persuade governments of the need to take appropriate and effective action to promote and protect the health of the public.

For example, in the field of tobacco control, despite the substantial differences in smoking patterns by social class, there is still debate in England about the need for a comprehensive approach to protect workers from second hand smoke. This is despite evidence that workplace smoking restrictions help individuals reduce tobacco consumption24 and that the limits on smoking in public places introduced into Eire and New York have been associated with substantial reductions in consumption.25,26 In the field of tobacco control, an emphasis on an educational approach may if anything have served to increase inequalities.

Another public health challenge is the substantial rise in alcohol consumption and binge drinking particularly in young people. Given that alcohol prices are now at their lowest in relative terms for over 30 years, and that alcohol is widely advertized and promoted, with cut price discounts a regular feature of bars and clubs, it would be extremely surprising if there had not been significant rises in consumption.27 Effective public health action will require not only education but regulatory and fiscal approaches. As a public health community we may rightly be challenged that we have failed to raise the profile of this issue to a sufficient extent, and have not succeeded in making the case for modest price rises and limits on availability a key part of a healthy public health policy on alcohol.

As the population ages, the key public health challenge is not just life expectancy, but how many years of life are lived with good health. Although the population of the UK has been living longer over the past 20 years, the extra years have not necessarily been lived in good health. Life expectancy and healthy life expectancy (expected years of life in good or fairly good health) both increased between 1981 and 2001, but life expectancy increased at a faster rate than healthy life expectancy.28

Promotion of health in older people and effective treatment of chronic diseases through collaboration between patients, primary and secondary care will be crucial in addressing this issue.

In conclusion, we would argue that public health professionals have made a major contribution to many of the public health successes of the last 30 years. We continue to face new challenges, not least emerging infections such as SARS and the ever present threat of an influenzae pandemic. As a profession, public health should be ready to identify new challenges, work with others to raise the profile of public health in the national consciousness, and to act as advocates for the full range of public health action as required. From the early days of sanitary reform and slum clearance, there has always been opposition to public health action in one form or another. We need to recognise that the new public health challenges may bring us into conflict with different groups, which will include those with powerful vested interests. Building a robust consensus from across the political spectrum to support public health action where needed will be a key skill for the public health advocates of tomorrow.

References

- 1.Wanless D. Securing Good Health for the Whole Population. London: HM Treasury, 2004

- 2.Public Health Achievements of the Twentieth Century. MMWR Weekly 1999;48: 241-3 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Public Health Achievements of the Twentieth Century. In: Pencheon D, Guest C, Melzer D, Muir Gray JA. Oxford Handbook of Public Health Practice, Introduction to Section 4. Oxford: OUP: 178

- 4.Office for National Statistics. Life Expectancy. http://www.statistics.gov.uk/cci/nugget.asp?id=881 Accessed June 2004

- 5.Public Health in England. Report of the Committee of Inquiry into the Future Development of the Public Health Function. London: HMSO, 1988

- 6.Food and Drink Federation. Dramatic Fall In Food Poisoning Case, Press Notice, 13 June 2005

- 7.Aceijas C, Stimson GV, Hickman M, Rhodes T, United Nations Reference Group on HIV/AIDS Prevention and Care among IDU in Developing and Transitional Countries. Global overview of injecting drug use and HIV infection among injecting drug users. AIDS 2004;18: 2295-303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rutherford WH, Greefield Tony, Hayes HRM, Nelson JK. Medical Effects Of Seat Belt Legislation In The United Kingdom: Research Report Number 13, Department Of Health And Social Security. Office Of The Chief Scientist. London: HMSO, 1985

- 9.Office for National Statistics. Road Accident Casualties: By Road User Type And Severity 1992-2002: Annual Abstract Of Statistics. London: Office for National Statistics, 2004

- 10.National Institute for Mental Health in England. Second Annual Report on National Suicide Prevention Strategy for England. London: NIMHE, 2005

- 11.Hawton K, Townsend E, Deeks J, et al. Effects of change in legislation on pack size of paracetamol and salicylate on self-poisoning in the United Kingdom: before and after study. BMJ 2001;322: 1203-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sir Donald Acheson. Independent Inquiry in Health. London: Stationery Office, 1998

- 13.Dahlgren G, Whitehead M. Policies And Strategies To Promote Social Equity In Health. Stockholm: Institute of Futures Studies, 1991

- 14.Kelly M, Capewell S. Relative Contributions Of Changes In Risk Factors And Treatment To The Reduction In Coronary Disease Mortality. Briefing paper. London: Health Development Agency, 2004

- 15.Department for Environment Food and Rural Affairs. Family Food 2001/2. London: DEFRA, 2004

- 16.Department of Health. Smoking, Drinking And Drug Use Among Young People In England In 2004: Headline Figures [www.dh.gov.uk/PublicationsAndStatistics] Accessed November 2005

- 17.Office for National Statistics. Cancer Survival: England and Wales 1991-2001. London: ONS, 2003

- 18.Lung and Asthma Information Agency. Trends in Hospital Admissions and Deaths From Asthma, Fact Sheet 2002/1. London: Public Health Department. St George's Medical School, 2002

- 19.Peto R. Mortality from breast cancer in UK has decreased suddenly. BMJ 1998;317: 476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shaw M, Davey Smith G, Dorling D. Health inequalities and New Labour: how the promises compare with real progress BMJ 2005;330: 1016-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Law MR, Morris JK. Why is mortality higher in poorer areas and in more northern areas of England and Wales? J Epidemiol Commun Health 1998;52: 344-52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Donaldson L. On the State of the Public Health: The annual report of the Chief Medical Officer of the Department of Health 2001; London: Department of Health, 2001

- 23.World Health Organization. Global WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. Geneva: WHO, 2003

- 24.Fichtenberg CM, Glantz SA. Effect of smoke-free workplaces on smoking behaviour: systematic review. BMJ 2002;325: 188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gottlieb S. New York's war on tobacco produces record fall in smoking. BMJ News 2004;328: 1222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Department of Health and Children. 7,000 Fewer Smokers in Ireland. Press release. London: DoH, 2004

- 27.Academy of Medical Sciences. Calling Time. The Nation's Drinking As A Major Health Issue. A report from the academy of medical sciences. London: AMS, 2004

- 28.Office for National Statistics. Health Expectancy. Living Longer, More Years In Poor Health. London: ONS, 2004