Abstract

Homology modeling of the α-subunit of Na+K+-ATPase, a representative member of P-type ion transporting ATPases, was carried out to identify the cation (three Na+ and two K+) binding sites in the transmembrane region, based on the two atomic models of Ca2+-ATPase (Ca2+-bound form for Na+, unbound form for K+). A search for potential cation binding sites throughout the atomic models involved calculation of the valence expected from the disposition of oxygen atoms in the model, including water molecules. This search identified three positions for Na+ and two for K+ at which high affinity for the respective cation is expected. In the models presented, Na+- and K+-binding sites are formed at different levels with respect to the membrane, by rearrangements of the transmembrane helices. These rearrangements ensure that release of one type of cation coordinates with the binding of the other. Cations of different radii are accommodated by the use of amino acid residues located on different faces of the helices. Our models readily explain many mutational and biochemical results, including different binding stoichiometry and affinities for Na+ and K+.

Na+K+-ATPase, a representative member of the P-type ATPase superfamily, exists in every mammalian cell, where it pumps three Na+ and two K+ in opposite directions by using the chemical energy of ATP (1, 2). The pumping reaction is electrogenic and plays an important role in establishing a membrane potential. The subunit composition of the Na+K+-ATPase is tissue-specific. Nevertheless its α subunit, the catalytic subunit, is common to all of the subtypes and possesses high sequence similarity with other P-type ATPases (3), such as the sarco(endo)plasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA) and the gastric H+K+-ATPase.

To elucidate the molecular mechanism of ion transport by Na+K+-ATPase, it is crucial to identify the amino acid residues involved in the binding of the cations to be transported. Although many mutational and biochemical studies have been carried out, the cation binding sites have not been clearly defined; in particular, the third Na+-binding site unique to the Na+K+-ATPase. Homology modeling is a useful means to approach this problem, because the structures of the Ca2+-ATPase of skeletal muscle sarcoplasmic reticulum (SERCA1a) have been determined in the Ca2+-bound (4) and unbound (5) forms, which are thought to correspond to the Na+- and K+-bound forms of Na+K+-ATPase. The overall similarity of the transmembrane sequences between Na+K+- and Ca2+-ATPases is ≈40%. In general, with this level of similarity, accurate models may not be obtained (6) because of ambiguities in alignment. Nevertheless, the similarity is substantially higher (≈60%) for the three (M4–M6) helices that form cation binding sites in the Ca2+-ATPase (Fig. 1); also, sequence variability within Na+K+-ATPases of different origins can be used to identify the lipid-exposed face of the transmembrane helices (7). With this information, homology modeling of the transmembrane sector appears to be quite feasible, and candidates for cation binding sites may be identified by examining valence maps (8). To make a valence map, the cation of interest is placed on a finely sampled grid in the model and the expected valence is calculated for each point from the distances between the cation and the surrounding atoms (9). This method has been successful with Ca2+- and Na+-biding proteins (8, 10).

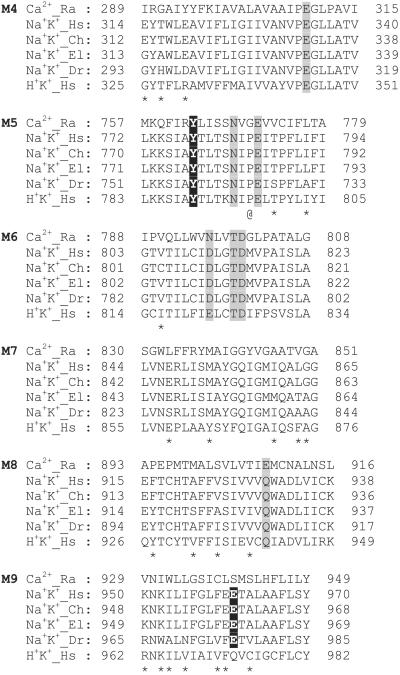

Fig 1.

Alignment of amino acid sequences of closely related P-type ATPases: Ca2+, sarco(endo)plasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA1a); Na+K+, Na+K+-ATPase α subunit; H+K+, H+K+-ATPase α subunit. Only the transmembrane helices M4–M9 are shown. The residues for which side chain oxygens contribute to Ca2+ binding in Ca2+-ATPase (4) are shaded. The residues for which side chains contribute to Na+-binding site III in Na+K+-ATPase are shown in white letters against a black background. Asterisks indicate variable residues within the Na+K+-ATPases of different origins. @, The residue that functions as a pivot in the bending of M5 [Gly-750 in Ca2+-ATPase (5)]. Numbers flanking each amino acid sequence indicate the numbers of the residue at the start and end of the sequence. Hs, Homo sapiens; Ch, chicken; El, European eel; Dr, Drosophila melanogaster; Ra, rabbit.

We report here that homology modeling and valence searching resulted in unambiguous identification of three Na+ and two K+ binding sites in the atomic models of Na+K+-ATPase. These binding sites are consistent with many biological and mutational results. The models also explain the different binding constants (mM−1 for Na+ and μM−1 for K+; ref. 11) and the different stoichiometry for Na+ and K+.

Materials and Methods

Amino Acid Sequence Alignment and Homology Modeling of Na+K+-ATPase.

The amino acid sequence of human Na+K+-ATPase α1 was aligned with that of rabbit SERCA1a, initially with the program dialign (12), and adjusted manually. Automatic alignment was reliable for only 4 (M3–M6) of the 10 transmembrane helices, because other helices bear too low a similarity (<40%). For aligning these helices, sequence variability within Na+K+-ATPases of different origins (eight species; only four distant ones are shown in Fig. 1) was examined to determine the face of the helix exposed to lipid (7). Homology modeling of the Na+K+-ATPase was carried out using the MODELLER4 package (6), based on the atomic models of SERCA1a for the Ca2+-bound form (E1Ca2+; PDB ID code ; ref. 4) and the thapsigargin-bound form [E2(TG); ; ref. 5].

Care was taken to make the coordination geometry most favorable, wherever the valence calculation gave high scores. Conformations of a few residues were therefore adjusted manually within well allowed ranges. Energy minimization was then carried out with SYBYL 6.4 (Tripos Associates, St. Louis), using AMBER force field (13). The geometry of the constructed model was evaluated with PROCHECK (14), and corrected manually using TURBO-FRODO (http://afmb.cnrs-mrs.fr). These procedures were iterated several times.

Search Strategy for the Ion Binding Sites.

To identify the ion binding sites, expected valence (8) was calculated throughout the constructed model at a 0.1-Å interval in all three directions and a valence map was made. Because the ideal valence value is 1.0 for monovalent cations, 0.9 was set as the threshold for the candidates. To take into account the contribution of water molecules, cavities of large enough dimensions for water molecules were mapped inside the models by using WHATIF (15). The valence maps were then calculated, including the water molecules placed in the cavities. These steps are illustrated in Fig. 6, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site, www.pnas.org.

Results

Amino Acid Sequence Alignment and Homology Modeling.

Fig. 1 shows the alignment of amino acid sequences for the transmembrane part of closely related P-type ATPases. The sequences are highly conserved for the helices (M4–M6 and M8) that contain residues that form the Ca2+-binding sites in SERCA1a (shaded in Fig. 1; ref. 4) but not for the others (35.8% similarity), hampering automatic alignments. Nonetheless, natural sequence variability reduced the possibilities for different alignments considerably. This is because lipid-facing residues tend to be variable, whereas those involved in helix–helix contacts tend to be conserved (7). As shown in Fig. 2, variable residues formed well defined faces (16, 17), in particular, on the M8 and M9 helices. As a result, two negatively charged residues, Gln-930 (M8) and Glu-961 (M9), were oriented toward the center of the molecule. Fig. 3 presents a view along the membrane plane of the constructed models of Na+K+-ATPase in Na+- and K+-bound forms.

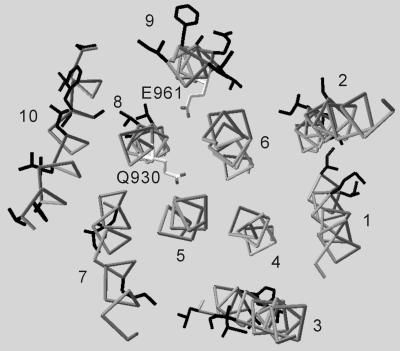

Fig 2.

Variable residues in the transmembrane part of the Na+K+-ATPase. The constructed model for the Na+-bound form is viewed roughly normal to the membrane from the cytoplasmic side. Transmembrane helices are numbered. Variable residues (shown in black) among Na+K+-ATPase of different origins are exposed to lipids, whereas Q930 (M8) and E961 (M9) orient toward the center of the transmembrane region.

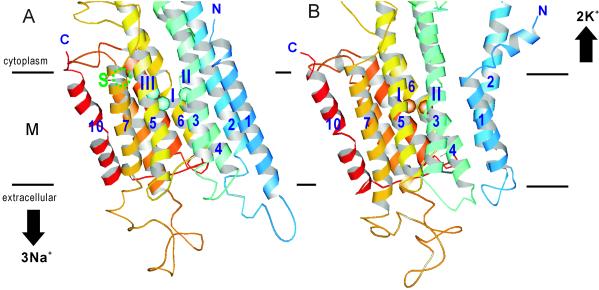

Fig 3.

Ribbon representation of the transmembrane part (M) of the constructed model of the Na+K+-ATPase in Na+- (A) and K+-bound (B) forms. α-Helices are numbered. Horizontal bars represent the boundaries of the hydrophobic core of the lipid bilayer. Cyan spheres in A represent Na+ ions (I–III), and orange spheres in B represent K+ ions (I and II). Site S, at which valence is slightly higher than 0.9, is also shown in A. Color changes gradually from the N terminus (N, blue) to the C terminus (C, red). Orientations of the models follow those of SERCA1a (5). Modeling of the cytoplasmic domains is not included in this figure. The figure was prepared with molscript (41).

Identification of the Cation Binding Sites.

Valence searching has proven to be a powerful method for identifying metal binding sites in atomic models (8, 10). The calculation exploits an empirical expression between the bond length and the bond strength of a metal ion–oxygen pair (9). As a test, we calculated the valence map for Ca2+ with the atomic model of SERCA1a (PDB ID code ). The map showed two sites of high valence (>1.6; ideally 2.0), precisely at the positions identified by x-ray crystallography (4). The valence map for Na+ calculated with the model of Na+K+-ATPase readily showed two sites (I and II) of 0.9 or higher at the positions equivalent to the Ca2+-binding sites in the Ca2+-ATPase. Because the amino acid residues that contribute to sites I and II in Ca2+-ATPase are virtually identical to those in Na+K+-ATPases (Figs. 1 and 5), this result was expected. However, outside of these two sites, the valence was <0.6. Therefore, the contribution of water molecules was incorporated and new valences maps were calculated. At two positions (sites III and S), valence was higher than 0.9, provided that two water molecules contribute (see Fig. 6D). Site III is contiguous to site I, surrounded by the M5, M6, and M9 helices (Fig. 5B). In contrast, site S is nearly “on” the M7 helix (near Glu-847), isolated from the other sites and close to (or possibly above) the boundary of the hydrophobic core of the lipid bilayer (see Figs. 3 and 6). Also, Glu-847 is substituted by Ser in Drosophila Na+K+-ATPase (Fig. 1). Hence, it seems unlikely that site S represents the third Na+-binding site.

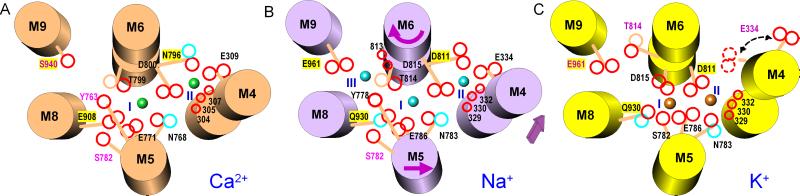

Fig 5.

Schematic diagrams for Ca2+-binding sites of Ca2+-ATPase (A), and Na+- (B) and K+-binding (C) sites of Na+K+-ATPase. The transmembrane helices (cylinders) are viewed from the cytoplasmic side. Arrows in B represent the directions of movements from Na+-bound (B) to K+-bound form (C); the arrow in C indicates two possible conformations of Glu-334. Cyan and orange spheres represent Na+ and K+, respectively. Red circles, oxygen atoms (carbonyl oxygen atoms appear smaller); blue circles, nitrogen; orange circles, carbon. Residue numbers with yellow background are those different between Ca2+-ATPase and Na+K+-ATPase α1. Residue numbers in pink specify those not directly involved in the coordination of the bound cation.

Details of the Na+-Binding Sites.

Fig. 4 and Table 1 show the coordination geometry of the Na+-binding sites. The valence, coordination number, and distances from the coordinating oxygen atoms are all appropriate for high-affinity Na+-binding sites (10).

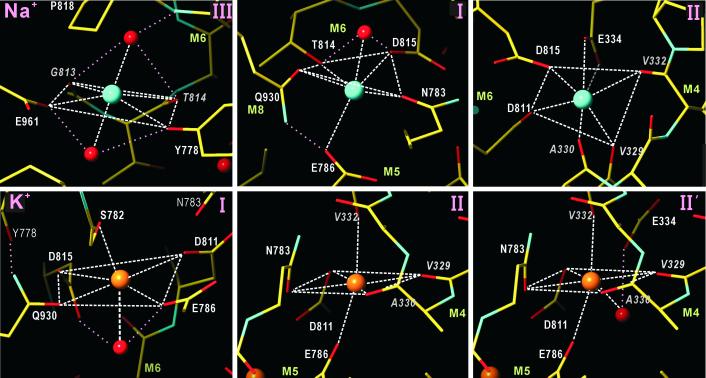

Fig 4.

Coordination geometry of Na+ and K+ in Na+K+-ATPase. Spheres represent Na+ (cyan), K+ (orange), and water (red). Dotted lines in pink show some of the potential hydrogen bonds. The Roman numeral in the top right corner refers to the binding site shown in Figs. 3 and 5. Site II′ for K+ is the same as site II, except for the contribution of Glu-334 through a water molecule.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Na+- and K+-binding sites in the homology models of Na+K+-ATPase

| Binding site

|

Valence

|

Distance, Å

|

No. of coordinating atoms | Coordinating residues | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Side chain | Main chain | Water | M4 | M5 | M6 | M8 | M9 | |||

| Na+ I | 1.12 | 2.42–2.57 | 5 | 0 | 1 | N783 | T814 | Q930 | ||

| E786 | D815 | |||||||||

| Na+ II | 0.97 | 2.43–3.03 | 4 | 3 | 0 | V329 | D811 | |||

| A330 | D815 | |||||||||

| V332 | ||||||||||

| E334 | ||||||||||

| Na+ III | 0.96 | 2.50–2.83 | 2 | 2 | 2 | Y778 | G813 | E961 | ||

| T814 | ||||||||||

| K+ I | 1.12 | 2.63–2.80 | 5 | 0 | 1 | S782 | D811 | Q930 | ||

| E786 | D815 | |||||||||

| K+ II | 1.17 | 2.61–2.81 | 3 | 3 | (1) | V329 | N783, | D811 | ||

| A330 | E786 | |||||||||

| V332 | ||||||||||

Calculated using the program kindly provided by E. Di Cera (8).

Distance between the bound cation and the coordinating atoms.

The residues in italic letters indicate that the carbonyl oxygen is used for coordination. Those in bold are unique to either Na+ or K+ binding. Double underscores indicate that the residues are used for coordination of two ions. The residue numbers refer to those of human Na+K+-ATPase α1.

Because sites I and II are formed by residues equivalent to those in SERCA1a (Figs. 1 and 5) and because the ionic radii are similar (0.95 Å for Na+ and 0.99 Å for Ca2+), they inherit all of the features found with the Ca2+-binding sites of SERCA1a. As summarized in Fig. 5 and Table 1, site I is formed entirely by side chain oxygen atoms of residues on three helices (M5, M6 and M8). Site II is formed almost “on” the M4 helix with three main chain carbonyls plus four side chain oxygen atoms (Asp-811 and Asp-815 on M6 and Glu-334 on M4). Asp-815 is the only residue coordinating two Na+ ions. Site III is unique to Na+K+-ATPase and contiguous to site I (Fig. 5B). The carbonyls of Gly-813 and Thr-814 (M6), the hydroxyl of Tyr-778 (M5), and the carboxyl of Glu-961 (M9) contribute to this site. Two water molecules are involved. As shown in Fig. 4, these water molecules appear to be well fixed by hydrogen bonds and by van der Waals contacts with Pro-818 and Thr-814.

Details of the K+-Binding Sites.

The strategy for locating K+-binding sites was identical to that for Na+. Two models were examined here because of two possible conformations of the Glu-334 side chain, as suggested for SERCA1a (5). One assumed the same conformation as in the E2(TG) model (Fig. 4, II); the other assumed that the side chain pointed toward K+, as in the E1Ca2+ form of SERCA1a (Fig. 4, II′). With the main chain conformation derived from the E2(TG) model, it was impossible for the Glu-334 side chain to coordinate K+ directly (only possible through a water molecule). However, even without the contribution of Glu-334, the valence map for K+ showed two well defined peaks of ≈1.1. The height of the next peak was ≈0.7 [at site S, as in the Na+-bound form (see Fig. 6D)].

Fig. 4 shows the details of the K+-binding sites. At either site, the coordination geometry of K+ appears very regular, involving six oxygen atoms placed ≈2.7 Å from K+ (Table 1). The distances are longer than those for Na+, reflecting the difference in ionic radius (1.33 Å for K+ and 0.95 Å for Na+). Accordingly, the valence values calculated for Na+ at these sites were <0.65, explaining the selectivity.

Site I is formed at a position very similar to that of the binding site I for Na+ (Figs. 3 and 5), and also involves one water molecule. Site II is again formed almost “on” the M4 helix (Fig. 5C). However, there are four conspicuous differences: (i) Despite the similar positions within the membrane plane, their positions normal to the membrane are different (Figs. 3 and 5). K+ sites are shifted toward the extracellular side, by one turn of an α-helix for site II (≈5.5 Å). (ii) This is because Asp-811, instead of Asp-815 (M6), and Glu-786 (M5) coordinate both K+ ions. (iii) In site I, Ser-782 is involved in K+ binding instead of Thr-814. (iv) In site II, Glu-334 coordinates Na+ directly but not K+, although it may coordinate K+ through a water molecule (Fig. 4, II′).

Discussion

In this study, we constructed models for the transmembrane part of the human Na+K+-ATPase α-subunit in the Na+- and K+-bound forms by homology modeling, based on the crystal structures of SERCA1a. These models led us to propose the locations of three Na+ and two K+ binding sites in the transmembrane sector (Figs. 3 and 5). The models also help us to understand why such large movements of the transmembrane helices are observed in SERCA1a between E1Ca2+ and E2(TG) forms (5).

Alignment of Amino Acid Sequences.

Because the modeling relies entirely on structural homology, amino acid sequence alignment is of prime importance. The overall similarity between Na+K+- and Ca2+-ATPases is ≈40% for the transmembrane part, precluding automatic alignment. Although many different alignments have been proposed, ours (Fig. 1) is identical to that of Sweadner (18), based on the “gapped-blast” method (19). The alignment proposed by Green (16) shifts the M9 sequence by four residues. Either alignment appears plausible with variable amino acid residues facing the lipid. In our model and that of Sweadner (18), Glu-961, reported to be implicated in Na+ binding (20, 21), is able to contribute to site III. In Green's alignment (16), Ala-965 comes to this position and the resultant model did not allow us to locate the third Na+-binding site.

From the sequence alignment, it is obvious that the residues directly involved in cation binding are virtually the same between Ca2+- and Na+K+-ATPases (Figs. 1 and 5). It is, therefore, expected that other functionally important residues will also be fully conserved. However, the M5 helix betrays our expectation in that a critical Gly on M5 (Gly-770) in the Ca2+-ATPase is replaced by Pro in Na+K+-ATPase (Pro-785; @ in Fig. 1). This Gly makes a tight contact with another Gly on M7 (Gly-841 in Ca2+-ATPase; conserved in Na+K+-ATPase) and appears to work as a pivot for the bending of M5 in Ca2+-ATPase (5). Na+K+-ATPase has a second proline (Pro-789) in M5 that replaces Cys-774 in Ca2+-ATPase. At first glance, the sequence (PEITP) may suggest an unwound conformation similar to M4 (PEGLP), but the dihedral angles for the Gly are prohibited for Ile at the corresponding position. Also a short loop connecting M5 and M6 bears a good homology between Ca2+- and Na+K+-ATPases (ALGLPEAL vs. IAGIPLPL), making unwinding of the M5 helix highly unlikely.

Introduction of Pro into an α-helix potentially causes energetic and steric problems. The energetic problem arises because of a break of the canonical hydrogen bonding pattern in the α-helix. This may not be serious, because hydrogen bonding in the transmembrane region appears possible even with hydrogen on Cα (22). The steric problem, which is introduced by replacing Gly with Pro, is avoided because Gly-858 (M7) substitutes for Val-844 at the corresponding position in Ca2+-ATPase. It is interesting to note that such pairwise substitutions are observed in many places.

Coordination of Na+ and K+.

To identify candidates for high-affinity cation binding sites, we calculated the expected valence for Na+ and K+ throughout the constructed models and made “valence maps” (see Fig. 6). Although we needed to incorporate one or two water molecules, the coordination number (6 or 7) and the geometry (octahedral, Fig. 4) also qualify the sites as Na+- and K+-binding sites (10, 23). Incorporation of two water molecules in one of the Na+-binding sites is reasonable. In the literature, four water molecules are found in a Na+-binding site with octahedral geometry (24).

As is shown in Fig. 4, coordination geometry is rather distorted for all of the three Na+ ions. In contrast, the geometry appears very regular for the K+ ions. Distorted coordination geometry for Na+ has also been described in oxidoreductase (25), which has a low affinity for Na+. Thus, the difference in coordination geometry nicely explains the large difference in binding affinity [mM−1 for Na+ and μM−1 for K+ (11)] of Na+K+-ATPase for the two cations.

Sites I and II for Na+ and K+ Binding.

There is already a large body of mutational results, including alanine-scanning mutagenesis of all oxygen-containing residues in the transmembrane region of Na+K+-ATPase (26). Mutation studies showed that Asn-783, Glu-786, Asp-811, and Asp-815 are critical for both Na+ and K+ binding (26–30) and that Ser-782 is implicated solely in K+ binding (31), whereas Thr-814 is solely implicated in Na+ binding (29). Chemical modification of Glu-786 suggested that this residue is critical for Na+ binding (17). These data are in complete agreement with our model (Fig. 5 and Table 1).

Because two conformations were possible for Glu-334 in K+ binding, the results of mutation experiments are of particular interest. In mutants Glu334Gln and Glu334Leu, the Na+ affinity is reduced 2- to 4-fold (32–34), whereas Glu334Ala and Glu334Asp are lethal (29, 32). Hence, the size of the side chain appears to be important. Because the phosphorylation rate of Glu334Gln is reduced, but can be rescued by oligomycin that stabilizes Na+ occlusion, it was concluded that Glu-334 is important for Na+ occlusion (34), in good agreement with our model. In the Glu334Gln mutant the apparent affinity for K+ is reduced >10-fold, but occlusion of K+ appears to occur, even though it is unstable (34). In contrast, the replacement of Glu-309, the corresponding residue in Ca2+-ATPase, by Gln results in a >1,000-fold reduction in apparent Ca2+ affinity and abolishes the binding of one Ca2+ (35, 36). It is, therefore, difficult to judge from these mutation data whether Glu-334 actually coordinates K+. The geometry of the binding site and the mutation data suggest that this residue might act as a gate (34).

Thus, it is not possible to propose an unequivocal model for K+ binding site II. Even without direct coordination, it is conceivable that Glu-334 affects the affinity, because this residue appears to seal the bound K+ from the cytoplasm through the long hydrophobic part of the side chain. Given the different behaviors of the mutants, the conformation of this residue may not be the same in Na+K+- and Ca2+-ATPases, possibly reflecting different interactions with residues on M1. With the alignment proposed, Glu-334 can form a hydrogen bond with Ser-101 (M1).

Site III for Na+ Binding.

Results from several mutational and biochemical studies support our model of Na+ binding site III. Mutation Glu961Ala depresses Na+ binding (21), whereas Glu961Gln does not (37). These results are consistent with our model, because only one of the carboxyl oxygen atoms of Glu-961 is used in binding Na+. Furthermore, Na+ binding protects against chemical modification of Glu-953 or Glu-954 of pig Na+K+-ATPase (corresponding to Glu-960 and Glu-961 in human) (20). The result that Tyr778Leu mutation solely affects Na+ binding (34) strongly supports our model, because Tyr-778 is used for only Na+ site III. Tyr-778 becomes accessible to a small sulfhydryl reagent when palytoxin binds to Na+K+-ATPase (38).

Given the importance of the last cation in inducing conformation changes that activate ATP hydrolysis, its binding site is expected to be common to all of the P-type ATPases. In Ca2+-ATPase, that is clearly site II. By analogy, site II in Na+K+-ATPase will be the binding site for the last Na+ ion, and the extra site will be the site for the first Na+ ion. Because sites I and II are contiguous, the extra site is expected to be located at the very end of the binding cavity, opposite to site II. The proposed location for the Na+ site III satisfies these requirements. The fact that mutation Tyr778Leu produces the largest effect on Na+ binding in all of the mutations made so far (34) supports this idea even further, because disruption of binding to the first Na+-binding site will abolish binding to the other sites. It is likely that correct positioning of M5 through Tyr-778 and M6 through Gly-813 and Thr-814 are critical for the binding of the second and third Na+ ions. The structure of SERCA1a suggests that Ca2+ ions enter the binding cavity through Glu-309 (ref. 5; Glu-334 in Na+K+-ATPase). The extra Pro in M5 might be necessary for the first Na+ ion to be able to reach site III through site I. That might be the reason why M5 possesses the sequence (PEITP), similar to M4 (PEGLP).

Reorganization of Transmembrane Helices in the E1Na+ to E2K+ Transition.

As described (5), rearrangements of transmembrane helices observed with the crystal structures of SERCA1a were perplexingly large. The meaning of such large movements is readily explained in our models of Na+K+-ATPase. The most important movements of the transmembrane helices in the transition from the Na+-bound E1Na+ form to the K+-bound E2K+ form will be (i) a shift of M4 toward the extracellular side by one turn of an α-helix, (ii) bending of the upper part of M5 toward M4, and (iii) nearly 90° rotation of the unwound part of M6 (5). As a consequence, profound reorganization of the binding residues takes place to accommodate a larger cation (K+) with a higher affinity, and also to ensure the release of Na+. The residues used in sites I and II are mostly the same: Only Ser-782 and Thr-814, and possibly Glu-334, are unique to either Na+ or K+ binding, whereas four residues (Asn-783, Glu-786, Asp-811, and Asp-815) alternate between sites (Fig. 5 and Table 1).

A larger space for K+ is provided by the bending of M5, which allows utilization of residues located on different faces of the transmembrane helices (Fig. 5). The bending of M5 brings Ser-782, not involved in Na+ binding, into the K+ site I, and also moves Asn-783, implicated in the Na+ site I, into the K+ site II. Glu-786, also in the Na+ site I, comes into an intermediate position between the two binding sites and coordinates both K+ ions.

To ensure that the release of Na+ and the binding of K+ occur simultaneously, the binding sites for Na+ and K+ are formed at different levels with respect to the membrane (Fig. 3). This is realized by changing the key coordinating residue from Asp-815 to Asp-811, located one turn toward the extracellular side on the M6 helix. The rotation of M6 moves Thr-814 away from the binding sites and Asp-815 from the intermediate position between sites I and II in E1Na+ to site I only in E2K+, but brings Asp-811 in to coordinate both K+ ions. Because Asp-815 and Asp-811 are distant by one turn of an α-helix, this distance must be compensated for by the movement of the M4 helix. In this sense, Asp-811, the only residue critically different from Ca2+-ATPase (Asn-796) of those involved in sites I and II, plays a key role in K+ binding. It is interesting to note that the Asn796Asp mutation abolishes Ca2+-ATPase activity, presumably by destroying site II (39). In E1Ca2+, the side chain of Asn-796 is stabilized by Asn-101 on M2 through a water molecule (4). The residue corresponding to Asn-101 in Na+K+-ATPase is Thr and fully conserved. Again, different interactions with other helices (in this case M2) appear to provide different behaviors.

Tyr-778 is a critical residue in Na+ site III in our model. Because Tyr-778 is located above the pivoting point of the M5 helix (Pro-785), its movement toward M4 in E1Na+ → E2K+ is large and abolishes site III for K+ binding. In this sense, the movement of M5 creates the different stoichiometry for Na+ and K+ of the Na+K+-ATPase. In this regard, it is interesting that mutation Pro785Ala reduces K+ affinity 6-fold without affecting Na+ affinity (40). Bulky residues around Glu-786, including Pro-785, might be important for accurate positioning of Glu-786 in K+ binding.

Thus, homology modeling of Na+K+-ATPase illuminates our understanding of the structural changes accompanying the E1–E2 transition revealed by x-ray crystallography of Ca2+-ATPase. The models described here for Na+K+-ATPase will serve as a useful guide for designing critical experiments until atomic structures of this important enzyme become available.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Yuji Sugita for his help with energy minimization calculations. We also thank David H. MacLennan and David B. McIntosh for their help in improving the manuscript. This work was supported in part by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports, Culture, and Technology of Japan (to C.T.).

Abbreviations

SERCA, sarco(endo)plasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase

References

- 1.Glynn I. M. (1993) J. Physiol. 462, 1-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaplan J. H. (2002) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 71, 511-535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Møller J. V., Jüul, B. & le Maire, M. (1996) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1286, 1-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Toyoshima C., Nakasako, M., Nomura, H. & Ogawa, H. (2000) Nature 405, 647-655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Toyoshima C. & Nomura, H. (2002) Nature 418, 605-611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sali A. & Blundell, T. L. (1993) J. Mol. Biol. 234, 779-815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baldwin J. M. (1993) EMBO J. 12, 1693-1703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nayal M. & Di Cera, E. (1994) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91, 817-821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown I. D. & Wu, K. K. (1976) Acta Crystallogr. B 32, 1957-1959. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nayal M. & Di Cera, E. (1996) J. Mol. Biol. 256, 228-234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matsui H. & Homareda, H. (1982) J. Biochem. (Tokyo) 92, 193-217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morgenstern B., Frech, K., Dress, A. & Werner, T. (1998) Bioinformatics 14, 290-294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cornell W. D., Cieplak, P., Bayly, C. I., Gould, I. R., Merz, K. M., Ferguson, D. M., Spellmeyer, D. C., Fox, T., Caldwell, J. W. & Kollman, P. A. (1995) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 117, 5179-5197. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Laskowski R. A., MacArthur, M. A., Moss, D. S. & Thornton, J. M. (1993) J. Appl. Crystallogr. 26, 283-291. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vriend G. (1990) J. Mol. Graphics 8, 52-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang P., Toyoshima, C., Yonekura, K., Green, N. M. & Stokes, D. L. (1998) Nature 392, 835-839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Argüello J. M. & Kaplan, J. H. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269, 6892-6899. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sweadner K. J. & Donnet, C. (2001) Biochem. J. 356, 685-704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Altschul S. F., Madden, T. L., Schaffer, A. A., Zhang, J., Zhang, Z., Miller, W. & Lipman, D. J. (1997) Nucleic Acids Res. 25, 3389-3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goldshleger R., Tal, D. M., Moorman, J., Stein, W. D. & Karlish, S. J. (1992) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89, 6911-6915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Van Huysse J. W. & Lingrel, J. B. (1993) Cell. Mol. Biol. Res. 39, 497-507. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Senes A., Ubarretxena-Belandia, I. & Engelman, D. M. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 9056-9061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Glusker J. P. (1991) Adv. Protein Chem. 42, 1-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang E. & Tulinsky, A. (1997) Biophys. Chem. 63, 185-200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.DeLaBarre B., Thompson, P. R., Wright, G. D. & Berghuis, A. M. (2000) Nat. Struct. Biol. 7, 238-244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Feng J. & Lingrel, J. B. (1994) Biochemistry 33, 4218-4224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pedersen P. A., Nielsen, J. M., Rasmussen, J. H. & Jorgensen, P. L. (1998) Biochemistry 37, 17818-17827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Feng J. & Lingrel, J. B. (1995) Cell. Mol. Biol. Res. 41, 29-37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vilsen B. (1995) Biochemistry 34, 1455-1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nielsen J. M., Pedersen, P. A., Karlish, S. J. & Jorgensen, P. L. (1998) Biochemistry 37, 1961-1968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Argüello J. M. & Lingrel, J. B. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270, 22764-22771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jewell-Motz E. A. & Lingrel, J. B. (1993) Biochemistry 32, 13523-13530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vilsen B. (1993) Biochemistry 32, 13340-13349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vilsen B., Ramlov, D. & Andersen, J. P. (1997) Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 834, 297-309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Skerjanc I. S., Toyofuku, T., Richardson, C. & MacLennan, D. H. (1993) J. Biol. Chem. 268, 15944-15950. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang Z., Lewis, D., Strock, C., Inesi, G., Nakasako, M., Nomura, H. & Toyoshima, C. (2000) Biochemistry 39, 8758-8767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Van Huysse J. W., Jewell, E. A. & Lingrel, J. B. (1993) Biochemistry 32, 819-826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guennoun S. & Horisberger, J.-D. (2000) FEBS Lett. 482, 144-148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Clarke D. M., Loo, T. W. & MacLennan, D. H. (1990) J. Biol. Chem. 265, 6262-6267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vilsen B. (1997) Biochemistry 36, 13312-13324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kraulis P. J. (1991) J. Appl. Crystallogr. 24, 246-950. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.