Abstract

Chromosomal instability (CIN) is a defining characteristic of most human cancers. Mutation of CIN genes increases the probability that whole chromosomes or large fractions of chromosomes are gained or lost during cell division. The consequence of CIN is an imbalance in the number of chromosomes per cell (aneuploidy) and an enhanced rate of loss of heterozygosity. A major question of cancer genetics is to what extent CIN, or any genetic instability, is an early event and consequently a driving force for tumor progression. In this article, we develop a mathematical framework for studying the effect of CIN on the somatic evolution of cancer. Specifically, we calculate the conditions for CIN to initiate the process of colorectal tumorigenesis before the inactivation of tumor suppressor genes.

The concept that tumors develop through the accumulation of genetic alterations of oncogenes and tumor suppressor (TSP) genes is now widely accepted as a fundamental principle of cancer biology. One of the strongest initial arguments came from mathematical modeling of epidemiologic data on retinoblastoma incidence in children. Quantitative analysis suggested that two genetic events were rate-limiting for cancer development, a notion validated by the subsequent identification of germ line and somatic mutations in the Rb TSP gene (1, 2).

Colorectal cancer is one of the best understood systems for studying the genetics of cancer progression. The process of tumorigenesis seems to be initiated by mutations of the APC TSP gene. Two types of genetic instability have been identified (3, 4). The predominant form of genetic instability in colorectal cancer (and most other solid tumors) is chromosomal instability (CIN). Microsatellite instability (MIN) occurs in 13% of sporadic colorectal cancers. MIN cancer cells have a 1,000-fold increase in the point mutation rate. A long-standing debate in cancer genetics is whether genetic instability is an early or late event in the process of tumorigenesis (5–11). In this article, we develop a mathematical model to explore the possibility that colon cancer is initiated by a CIN mutation.

The molecular basis for CIN is just beginning to be explored (12). A large number of gene alterations can give rise to CIN in Saccharomyces cerevisiae (13, 14). The genes include those involved in chromosome condensation, sister-chromatid cohesion, kinetochore structure and function, and microtubule formation and dynamics as well as checkpoints that monitor the progress of the cell cycle. To date, the only genes implicated in aneuploidy in human cancer cells are those of the latter class. Heterozygous mutations in the mitotic spindle checkpoint gene hBUB1 were detected in a small fraction of colorectal cancers with the CIN phenotype (15). These mutations in hBUB1 were shown to be dominant. Exogenous expression of the mutant gene conferred an abnormal spindle checkpoint and CIN to chromosomally stable cell lines (16). These results also confirmed cell-fusion studies that indicate that the CIN phenotype has a dominant quality and it might only require a single mutational “hit” to engender CIN (17).

The colon is organized into compartments of cells called crypts. It is widely believed that adenomas develop from normal stem cells located at the bases of normal crypts (18). The progeny of stem cells migrate up the crypt and continue to divide until they reach its midportion. Subsequently, the migrating epithelial cells stop dividing and instead differentiate to mature cells. When the differentiated cells reach the top of the crypt, they undergo apoptosis and are engulfed by stromal cells or shed into the lumen. This journey from the base of the crypt to its apex takes ≈3–6 days (19, 20). Normally, the birth rate of the colonic epithelial cells precisely equals the rate of loss from the crypt apex. If the birth/loss ratio increases, a neoplasm results.

Colorectal tumors progress through a series of clinical and histopathologic stages ranging from dysplastic crypts through small benign tumors to malignant cancers. This progression is the result of a series of genetic changes that involve activation of oncogenes and inactivation of TSP genes (21). Mutation of the APC gene is the earliest event yet identified in sporadic colorectal tumorigenesis, and it is estimated that >85% of colorectal tumors have somatic mutations of the APC gene (22).

The APC gene encodes a large multidomain protein that has many different sites for interaction with other proteins. Most APC mutations that are observed in patients lead to truncation of the encoded protein, with loss of the carboxyl-terminal sequences that interact with microtubules (22). Recent experiments in mouse cells bearing similarly mutated APC alleles have identified some karyotypic abnormalities that have been termed “CINs” (23, 24). Close inspection, however, reveals that the mutant cells actually tend to undergo polyploidization in whole-genome increments rather than showing elevated losses and gains of one or a few individual chromosomes (24). Because the latter pattern corresponds to that seen in CIN cancers, it remains unclear what the significance of the APC mouse data are in the context of cancer progression. Furthermore, some well characterized human colon cancer cell lines with APC mutations have chromosome complements that have remained perfectly stable and invariant over thousands of cell divisions in vitro (17, 25). Therefore, it is unlikely that APC inactivation itself triggers CIN in human colorectal cancer.

It is important to determine whether CIN precedes APC inactivation. Studies in mice, as well as in humans, have shown that in many cases, APC inactivation involves mutation of one allele and loss of the other. Such inactivations could occur in two ways. A mutation in one APC allele could occur first, followed by a loss of the second allele, or vice versa. In either case, the allelic loss event could be precipitated by CIN. Unfortunately, the precise timing of the emergence of CIN is difficult to measure as long as the genetic alterations underlying most CIN cancers have not been identified. We therefore developed a mathematical framework for studying the dynamics of colorectal cancer initiation. Following a long-standing tradition of cancer modeling (26–30), we use a stochastic approach.

A Mathematical Model of Tumor Initiation

A crypt is estimated to contain ≈1,000–4,000 cells; the whole colon in adults consists of ≈107 crypts. At the bottom of each crypt there are approximately four to six stem cells that replenish the whole crypt (31). For our model, we assume there are N cells in a crypt at risk of becoming precancer cells. If only the stem cells are at risk, then N ≈ 4–6. More generally, we expect N to be somewhere between 1 and 1,000.

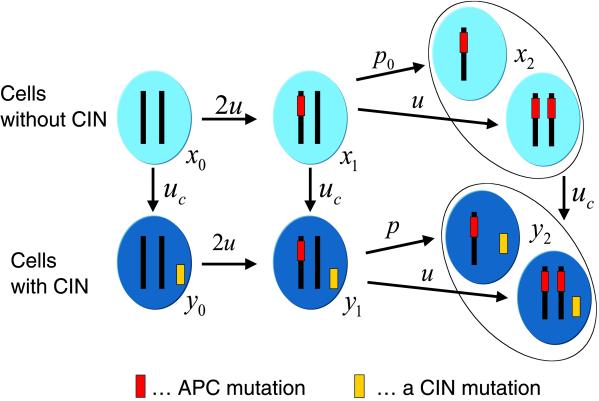

Consider the evolutionary dynamics of a single crypt with six different types of cells. Let x0, x1, and x2 denote the abundance of non-CIN cells with 0, 1, and 2 inactivated copies of APC, respectively. Let y0, y1, and y2 denote the abundance of corresponding CIN cells. Fig. 1 shows the mutation network. We assume that non-CIN cells with at least one functional APC gene have a relative reproductive rate of 1. This quantity defines the time scale of our analysis. Cells with two inactivated copies of APC have a reproductive rate of a > 1, which gives them a selective advantage and enables them to take over the crypt with a certain probability.

Fig 1.

Mutational network of cancer initiation describing inactivation of a TSP gene and activation of CIN. Normal cells, x0, have two functioning copies of the gene and no CIN. Cells with one inactivated copy, x1, arise from x0 cells at a rate of 2u; each copy can mutate with probability u per cell division. Cells with two inactivated copies of the TSP gene, x2, arise from x1 cells at a rate of u + p0. The parameter p0 describes the probability that the second copy of the TSP gene is lost during a cell division because of LOH. CIN cells, yi, arise from non-CIN cells, xi, at a rate of uc = 2ncu, where nc denotes the number of genes that cause CIN if a single copy of them is mutated or inactivated. CIN cells with two functioning copies of the TSP gene, y0, mutate into y1 cells at a rate of 2u. CIN cells of type y1 mutate to y2 cells at a rate of u + p, where p is the rate of LOH in CIN cells. We expect p to be much greater than u and p0. For simplicity, we neglect the possibility that APC might be inactivated by an LOH event followed by a point mutation. If CIN (or LOH in 5q) has a cost, then this pathway will contribute very little; otherwise it could enhance the relative success of CIN by a factor of ≈2.

Denote by u the probability that one copy of APC is inactivated during cell division. This inactivation can occur as a consequence of mutational events in the APC gene. We expect u ≈ 10−7 per cell division. The mutation probability from x0 to x1 is 2u, because either of the two copies of APC can become inactivated. The same holds for the mutation probability from y0 to y1.

There are two possibilities to proceed from x1 to x2. The second copy of APC can be inactivated by (i) another mutational event occurring with probability u or (ii) a loss of heterozygosity (LOH) event occurring with probability p0 per cell division. Hence the resulting mutation rate is u + p0. Similarly, y1 proceeds to y2 with a mutation rate of u + p, where p is the rate of LOH in CIN cells.

We assume that the crucial effect of CIN is to increase the rate of LOH, which implies p > p0 and p > u. Intuitively, the advantage of CIN for the cancer cell is to accelerate the loss of the second copy of a TSP gene. The cost of CIN is that copies of other genes are being eliminated, which might lead to nonviable cells or enhanced rates of apoptosis. There is evidence, however, that the presence of certain carcinogens confers a direct selective advantage on CIN cells (16). Furthermore, omitting certain checkpoints during the cell cycle could increase the rate of cell division. Hence, the reproductive rate, r, of CIN cells could be greater or smaller than 1. Table 1 gives a summary of the parameters of our system and their approximate values.

Table 1.

| Symbol | Parameter | Value |

|---|---|---|

| u | Mutation rate per gene | ≈10−7 |

| nc | Number of dominant CIN genes | 10–100 |

| p0 | Rate of LOH in normal cells | ≈10−7 |

| p | Rate of LOH in CIN cells | ≈10−2 |

| r | Reproductive rate of CIN cells | ? |

| a | Reproductive rate of APC−/− cells | >1 |

| n | Effective population size of crypt | 1–1,000 |

For the validity of our analysis only two conditions are important: (i) we need u ≪ 1/N2 (otherwise the stochastic dynamics do not proceed via mostly homogeneous states), and (ii) we need the selective advantage of APC−/− cells, a, to be sufficiently large such that the probability of fixation of such a cell in a crypt is close to 1 (otherwise the dynamics of tunneling is very complex). Both conditions are very plausible. Only for a simple representation of the final results do we need a separation of time scales of the form ut ≪ 1, uct ≪ 1, and pt ≫ 1, where t is the time scale of human life in days divided by the time of cell division of the colon cells that are at risk of becoming cancer cells. The mutation rates and LOH rates are expressed per gene per cell division. The relative reproductive rate of CIN cells, r, should be <1 if there is a cost of CIN. Certain carcinogens, however, can select for CIN, which would imply r > 1.

Whether there is any effective selection for or against CIN depends on the relative magnitude of the selection coefficient, r − 1, compared with the dominant mutational process and compared with the reciprocal of the population size. If the effective population size, N, is small, then the evolutionary dynamics are dominated by random drift. If the rate of LOH in CIN cells is large, then the effect of selection is outpaced by LOH. Let us define s0: = max(1/N, ). CIN is positively selected if r − 1 > s0, and CIN is negatively selected if r − 1 < −s0. CIN is effectively neutral if s0 > r − 1 > −s0.

). CIN is positively selected if r − 1 > s0, and CIN is negatively selected if r − 1 < −s0. CIN is effectively neutral if s0 > r − 1 > −s0.

In our model, a CIN cell carries a mutation that results in an increased rate of LOH. A number of mechanisms can lead to LOH including nondisjunction of chromosomes (with or without duplication), mitotic recombination, gene conversion, interstitial deletion, or a double-strand break resulting in the loss of a chromosome arm. In this article, we include any such mechanism leading to an increased rate of LOH as CIN. Hence, any mutation that increases the rate of one of these processes qualifies as a CIN mutation. Lengauer et al. (17) estimated the rate of loss of chromosomes in CIN cell lines to be p = 0.01 per cell division. Note, however, that even such a high rate of LOH does not imply that CIN cells must have LOH in almost all their loci, because there is conceivably selection against LOH in many loci.

We assume there are nc genes such that a single mutation in any one of these genes can cause CIN. Hence the mutation rate from xi to yi is given by 2ncu.

Let us derive an analytic understanding of the underlying evolutionary dynamics. The full stochastic process describing the somatic evolution of a crypt leads to a fairly intractable system of equations. The trick that allows us to proceed is to realize that, for relevant parameter values, only a small number of states of the stochastic process are long-lived. These states correspond to homogeneous crypts, where all cells are of a particular type. If u ≪ 1/N2, then the system will spend a long time in these homogeneous states; the probability to find more than one cell type in a single crypt at a particular time is very small.

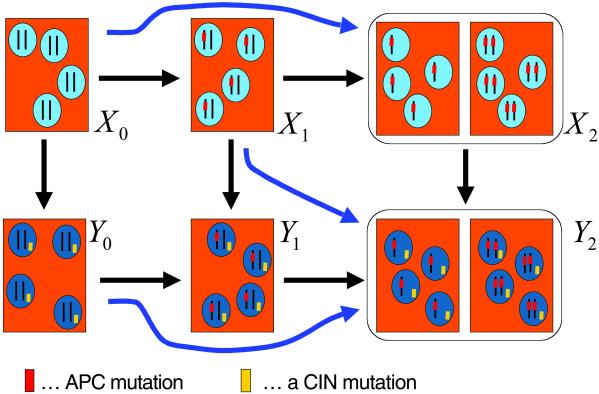

Denote by Xi and Yi the homogeneous states that contain only cells of type xi and yi, respectively. The evolutionary dynamics are described by a linear Kolmogorov forward equation, which can be solved analytically. An interesting phenomenon in this system is “stochastic tunneling.” Consider two consecutive transitions, say X1 → Y1 → Y2. If the rate of mutation from y1 to y2 cells is much faster than the rate of fixation of y1 cells in a mixed population containing x1 and y1 cells, and if y2 cells have a clear selective advantage, then the system might never reach state Y1 but instead “tunnel” from X1 to Y2. As outlined in Fig. 2, there are three stochastic tunnels in our system, and we can calculate the parameter conditions for individual tunnels to be open or closed. It turns out there are eight cases that can be classified into five reaction networks (Fig. 3). Each reaction network specifies a linear differential equation, which can be solved analytically.

Fig 2.

The early steps of colon cancer occur in small crypts that contain a few thousand cells. The whole crypt is replenished from a small number of stem cells. The effective population size of the crypt, N, with respect to the somatic evolution of cancer might be of the order of 10 cells. As long as N2 ≪ 1/u (where u ≈ 10−7–10−6), then there is a high probability that at any one time crypts contain cells of only one type. Hence, we can investigate a stochastic process describing transitions among six different states, X0, X1, X2, Y0, Y1, and Y2, referring to homogeneous crypts of cell type x0, x1, x2, y0, y1, and y2, respectively. The transitions reflect the mutational network of Fig. 1. In addition, there are three stochastic tunnels. For certain parameter values, the system can tunnel from X0 to X2 without reaching X1. Similarly, there are tunnels from Y0 to Y2 and from X1 to Y2. Tunnels occur if the second step in a consecutive transition is much faster than the first one and if the final cell has a strong selective advantage.

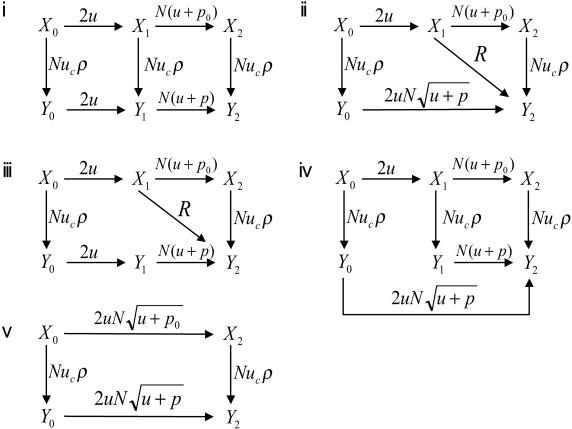

Fig 3.

Transition rates and stochastic tunnels of the probabilistic process describing the dynamics of early steps in colon cancer. The states X0, X1, and X2 refer to homogeneous crypts of non-CIN cells with 0, 1, and 2 inactivated copies of APC, respectively. The states Y0, Y1, and Y2 refer to homogeneous crypts of CIN cells with 0, 1, and 2 inactivated copies of APC, respectively. The probability that a CIN cell with reproductive rate r reaches fixation in a crypt of N cells is given by ρ = rN−1(1 − r)/(1 − rN). The mutation rate per gene per cell division is given by u. The mutation rate from non-CIN cells to CIN cells is given by uc = 2ncu, where nc is the number of genes that cause CIN if one copy of them is mutated. The rate of LOH in CIN and non-CIN cells is given by p and p0, respectively. Let γ = (1 − r)2rN−2 if r < 1 and γ = (r − 1)/{rN log[N(r − 1)/r]} if r > 1. Network i occurs in two cases: (ia)  ≪ 1/N and |1 − r| ≪ 1/N and (ib)

≪ 1/N and |1 − r| ≪ 1/N and (ib)  ≪ 1/N and |1 − r| ≫ 1/N and p ≪ γ. Network ii occurs in three cases: (iia) if

≪ 1/N and |1 − r| ≫ 1/N and p ≪ γ. Network ii occurs in three cases: (iia) if  ≫ 1/N and |1 − r| ≪

≫ 1/N and |1 − r| ≪  , then R = Nuc

, then R = Nuc , (iib) if r < 1 and

, (iib) if r < 1 and  ≫ 1/N and 1 − r ≫

≫ 1/N and 1 − r ≫  , then R = Nucpr/(1 − r), and (iic) if r > 1 and

, then R = Nucpr/(1 − r), and (iic) if r > 1 and  ≫ 1/N and r − 1 ≫

≫ 1/N and r − 1 ≫  and p ≫ γ, then R = N2ucplog[N(r − 1)/r]. Network iii occurs if r < 1, p ≫ γ, and

and p ≫ γ, then R = N2ucplog[N(r − 1)/r]. Network iii occurs if r < 1, p ≫ γ, and  ≪ 1/N ≪ 1 − r; we have R = Nucpr/(1 − r). Network iv occurs if r > 1, p ≪ γ, and r − 1 ≫

≪ 1/N ≪ 1 − r; we have R = Nucpr/(1 − r). Network iv occurs if r > 1, p ≪ γ, and r − 1 ≫  ≫ 1/N. In addition, networks i–iv require that

≫ 1/N. In addition, networks i–iv require that  ≪ 1/N. Network v occurs if

≪ 1/N. Network v occurs if  ≫ 1/N. This is a complete classification of all generic cases.

≫ 1/N. This is a complete classification of all generic cases.

The crucial question is whether the system reaches X2 before Y2 or vice versa. In the first case, APC inactivation occurs in a non-CIN cell. In the second case, APC inactivation occurs in a CIN cell, and hence CIN causes inactivation of APC (because p ≫ u). The answer can be stated in a concise form provided there is a separation of time scales: for the relevant time scale t of human life, we have ut ≪ 1, p0t ≪ 1, and pt ≫ 1. The condition for CIN to cause inactivation of the second APC gene then can be expressed as the number of CIN genes exceeding a certain threshold value,

|

Here K(N, p, r) = (1/2)min{1/(2ρ), C}. The probability that a single CIN cell will reach fixation in a crypt is given by ρ = rN−1(1 − r)/(1 − rN). There are three possibilities for C. If CIN is neutral, then C = 1/[(Nρ + 1) ]. If CIN is negatively selected, then C = (1 − r)/(rp). If CIN is positively selected, then C = 1/{pN log[N(r − 1)/r] + Nρ

]. If CIN is negatively selected, then C = (1 − r)/(rp). If CIN is positively selected, then C = 1/{pN log[N(r − 1)/r] + Nρ }.

}.

The “threshold of CIN” (Eq. 1) has to be interpreted as follows. A necessary condition for CIN to precede APC inactivation is that p0 is not much larger than u. If p0 ≫ u, then it is difficult for a CIN gene that requires a point mutation to precede APC. If instead p0 ≈ u, then the decisive factor of Eq. 1 is K(N, p, r).

For small N and r ≈ 1 (more precisely for |1 − r| ≪ 1/N), we have K = N/4. Thus nc > (1 + p0/u)(N/4). If p0 ≈ u and N = 10, we need nc > 5. In this case, five dominant CIN genes in the human genome are enough for CIN to cause inactivation of APC in 50% of dysplastic crypts. For large N and a significant cost of CIN, we have K = (1 − r)/(2rp). If p0 ≈ u, r = 0.8, and p = 0.01, we have nc > 25. Table 2 provides further examples.

Table 2.

The critical number of CIN genes required for CIN mutations to occur before inactivation of the APC gene and hence to initiate colon cancer

|

N

|

p0/u = 1 | p0/u = 10 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r = 0.8 | r = 1.0 | r = 1.2 | r = 0.8 | r = 1.0 | r = 1.2 | |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| 10 | 17 | 5 | 3 | 92 | 28 | 14 |

| 100 | 25 | 5 | 1 | 138 | 28 | 2 |

If the number of CIN-causing genes, nc, is greater than the critical number shown, then CIN occurs before inactivation of APC in the majority of colon cancers. N denotes the effective cell number in a crypt, u is the mutation rate per gene per cell division, p0 is the rate of LOH in a non-CIN cell per cell division, and r is the relative reproductive rate of CIN cells. CIN can be effectively neutral, positively selected, or negatively selected for different choices of parameters. If |1 − r| is less than 1/N then CIN is effectively neutral. Note that for a wide range of parameter choices the required number of CIN genes is small, which makes it likely that CIN initiates colon cancer progression.

We can also consider CIN loci where a single point mutation or an LOH event triggers CIN. If there are n′c such genes, then the mutation rate from xi to yi is given by 2n′c(u + p0), and the threshold of CIN becomes n′c > K(N, p, r). In this case, the magnitude of p0 is unimportant. Alternatively, we can consider CIN genes that require inactivation of both alleles. Although the cell-fusion experiments published thus far suggest that CIN is a dominant trait (17), it is possible that several CIN genes act in a recessive manner. Such genes are unlikely candidates for preceding APC unless they themselves provide a significant selective advantage.

Discussion

In this article, we have developed a mathematical framework for the dynamics of cancer initiation. Specifically, we have calculated conditions for CIN to cause inactivation of the first TSP gene in colon cancer. If the number of CIN genes in the human genome exceeds a critical value, then there is a high probability that inactivation of APC happens after a CIN mutation. For a wide range of parameter values, the required number of CIN genes is small (Table 2), which makes it possible that colon cancer is indeed initiated by CIN mutations.

In this case, the most likely sequence of events is the following: (i) if there is a significant selective cost of CIN, then the first event will be a point mutation in APC, followed by a CIN mutation, followed by LOH in APC; and (ii) if CIN is effectively neutral (or positively selected), then the first event could be either the CIN mutation or a point mutation in APC, followed by LOH in APC. In both cases, the first phenotypic change of the cell is the CIN mutation. Hence, it is possible that a genetic instability mutation, not a mutation in a TSP gene, initiates colon cancer.

How can we test this hypothesis? The optimal way would be to identify the putative gene(s) conferring CIN and then determine the time during tumorigenesis when these mutations occur. This will be a challenging and lengthy endeavor. In the interim, it may be possible to determine whether dysplastic crypts have a CIN phenotype. Shih et al. (10) found that >90% of early adenomas (size 1–3 mm) had allelic imbalance: LOH in 1p, 5q, 8p, 15q, and 18q was found in 10, 55, 19, 28, and 28% of cases, respectively. These numbers are lower bounds because the experimental techniques for detecting LOH are complicated by the admixture of nonneoplastic cells within small tumors. It will be important to attempt to extend these results to dysplastic crypts. If CIN is frequent in such crypts, then our hypothesis would be confirmed.

Our model is also relevant to Knudson's early interpretation of retinoblastoma data. Let us assume that there was detailed information on the age incidence of dysplastic crypts (rather than fully developed colon cancers) and that these data suggested two rate-limiting steps (as per Knudson's model). The classical interpretation of such data would be that these two steps represent the inactivation of the two alleles of APC. Our analysis shows that the two rate-limiting steps might instead be one APC mutation and one CIN mutation; the third event, LOH in APC, would not be rate-limiting in a CIN cell. Hence, a two-hit curve for the elimination of a TSP gene is compatible with CIN.

The threshold of CIN (Eq. 1) depends among other parameters on the ratio of p0/u, where p0 is the rate of LOH in a non-CIN cell and u is the mutation rate. If p0 is much greater than u, then it is unlikely that CIN occurs before APC inactivation. In this case, however, the rate of LOH in non-CIN cells is so high that we would have to question the idea that cancers have CIN because it accelerates LOH events. It will be important to determine the rate of LOH in normal and CIN cells and compare both quantities to the mutation rate u. It will also be important to determine the number of cells in a crypt that can give rise to cancer. This requires a deeper understanding of colonic epithelial stem cell development and function.

In summary, we have developed a mathematical model to study the cellular dynamics of cancer initiation. The aim is to provide a quantitative framework for the ongoing debate about whether genetic instability mutations are early events in tumorigenesis. The most radical interpretation of our model is that for a wide range of realistic parameter values, CIN mutations seem to initiate colon cancer. Hence, we suggest that the first event in many sporadic neoplasias is a heritable alteration that affects genetic instability rather than cellular growth per se. We hope that this model will lead to a coherent framework for experimental tests of this essential feature of neoplasia.

Stochastic Tunnels.

Here we outline how to calculate transition rates among homogeneous states and conditions and rates for tunneling. Suppose there are three types of cells: a, b, and c. Assume a mutates to b with a rate of u1, whereas b mutates to c with a rate of u2. The reproductive rates of cells a, b, and c are 1, r, and rc, respectively. There are N cells. A, B, and C refer to homogeneous states where all N cells are of type a, b, and c, respectively.

We assume that the mutation rate u1 is so small that if a single mutant, b, appears it will either become extinct or go to fixation before a second mutant b arises. This is the case if u1 ≪ 1/N2. Next we assume that mutant c has a strong selective advantage; if a single cell of type c appears, it will be fixed with very high probability.

Under these assumptions, two scenarios are possible.

(i) No tunneling. A proceeds to B with a rate of Nu1ρ, and B proceeds to C with a rate of Nu2. Note the Nu1 is the rate at which b mutants are produced in a population of N cells of type a. The probability that a single b mutant reaches fixation is given by ρ = rN−1(1 − r)/(1 − rN). The Kolmogorov forward equations are given by Ȧ(t) = −Nu1ρA(t), Ḃ(t) = Nu1ρA(t) − Nu2B(t), and Ċ(t) = Nu2B(t). We use the notation A(t), B(t), and C(t) for the probability that the system is in state A, B, or C at time t. Obviously A(t) + B(t) + C(t) = 1. The initial condition is A(0) = 1.

(ii) Tunneling. A proceeds to C at a rate of R without ever reaching B. The Kolmogorov forward equation is given by Ȧ(t) = −RA(t), Ċ(t) = RA(t).

Tunneling takes place if the mutation rate u2 is large compared with the rate of fixation of a b mutant in an almost all a populations. The exact conditions for tunneling are as follows. Let s = rb − 1 and s0 = max(1/N, ). For s < 0 and |s| ≪ s0, tunneling occurs if u2 ≫ (1 − r)2rN−2; the rate is R = Nu1u2r/(1 − r). For s > 0 and s ≫ s0, tunneling occurs if u2 ≫ (r − 1)/{rN log[N(r − 1)/r]}; the rate is R = N2u1u2log[N(r − 1)/r]. For −s0 < s < s0, tunneling occurs if u2 ≫ 1/N2; the rate is R = Nu1

). For s < 0 and |s| ≪ s0, tunneling occurs if u2 ≫ (1 − r)2rN−2; the rate is R = Nu1u2r/(1 − r). For s > 0 and s ≫ s0, tunneling occurs if u2 ≫ (r − 1)/{rN log[N(r − 1)/r]}; the rate is R = N2u1u2log[N(r − 1)/r]. For −s0 < s < s0, tunneling occurs if u2 ≫ 1/N2; the rate is R = Nu1 . These results can be obtained from a detailed analysis of the underlying birth–death process.

. These results can be obtained from a detailed analysis of the underlying birth–death process.

MIN.

The model can also be extended to include MIN. There are Nm = 4–6 MIN genes that cause an increased point mutation rate when both copies are mutated (or silenced by methylation). In a MIN cell, the APC genes are inactivated at a rate of u′ = 10−4 per cell division. We can calculate the percentage of sporadic colorectal cancers that have MIN, CIN, or normal phenotype by the time of APC (or β-catenin) inactivation. Assuming that both MIN and CIN are roughly neutral, the ratio of normal/MIN/CIN is given by N to Nm to 4nc/(1 + p0/u).

Emergence of CIN in Large Populations of Cells.

We can also calculate the conditions for CIN to arise before inactivation of a TSP gene in large populations of cells. For large cell numbers, N, we can use deterministic population dynamics. Denote by x0, x1, and x2 the abundances of non-CIN cells with 0, 1, and 2 inactivated copies of the TSP gene, respectively. Similarly, y0, y1, and y2 denote the abundances of CIN cells with 0, 1, and 2 inactivated copies of the TSP gene. We are interested in the average time until one x2 or one y2 cell arises. Consider the following system of ordinary differential equations: ẋ0 = x0(1 − 2u − uc − φ), ẋ1 = x1(1 − uc − u − p0 − φ) + x02u, ẋ2 = x1(u + p0), ẏ0 = y0[r(1 − 2u) − φ] + x0uc, and ẏ1 = y1[r(1 − p) − φ] + y0r2u + x1uc, ẏ2 = y1rp. Here φ = x0 + x1 + r(y0 + y1) ensures constant population size. We do not consider replication of x2 or y2 cells because we want to calculate the time until a single cell of either type has been produced. We find that y2(t) will arise before x2(t) if nc > N*: = ¼(1 + p0/u) for (1 − r)t ≪ 1 [which implies (1 − r)t ≪ p] and nc > N*: = (1 + p0/u)(1 − r)/2rp for (1 − r)t ≫ 1. Remarkably, these conditions are very similar to those found for the stochastic process describing small population sizes. Therefore, the condition that CIN arises before inactivation of the first TSP gene is equivalent to the condition that CIN arises before inactivation of the next TSP gene at any stage of tumor progression.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by The Packard Foundation, the Ambrose Monell Foundation, the Leon Levy and Shelby White Initiatives Fund, Jeffrey Epstein, the Concern Foundation (to C.L.), the Damon Runyon–Walter Winchell Foundation's Cancer Research Fund (to P.V.J.), the Clayton Fund (to B.V.), and National Institutes of Health Grants CA43460 and CA62924.

Abbreviations

TSP, tumor suppressor

CIN, chromosomal instability

MIN, microsatellite instability

LOH, loss of heterozygosity

References

- 1.Knudson A. G. (1971) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 68, 820-823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Friend S. H., Bernards, R., Rogels, S., Weinberg, R. A., Rapaport, J. M., Albert, D. M. & Dryja, T. P. (1986) Nature 323, 643-646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lengauer C., Kinzler, K. W. & Vogelstein, B. (1998) Nature 396, 643-649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sen S. (2000) Curr. Opin. Oncol. 12, 82-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Loeb L. A., Springgate, C. F. & Battula, N. (1974) Cancer Res. 34, 2311-2321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Breivik J. & Gaudernack, G. (1999) Adv. Cancer Res. 76, 187-212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Breivik J. & Gaudernack, G. (1999) Semin. Cancer Biol. 9, 245-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tomlinson I. & Bodmer, W. (1999) Nat. Med. 5, 11-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li R., Sonik, A., Srindl, R., Rasnick, D. & Duesberg, P. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97, 3236-3241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shih I. M., Zhou, W., Goodman, S. N., Legnauer, C., Kinzler, K. W. & Vogelstein, B. (2001) Cancer Res. 61, 818-822. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marx J. (2002) Science 297, 544-546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maser R. S. & DePinho, R. A. (2002) Science 297, 565-569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kolodner R. D., Putnam, C. D. & Myung, K. (2002) Science 297, 552-557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nasmyth K. (2002) Science 297, 559-565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cahill D. P., Lengauer, C., Yu, J., Riggins, G. J., Willson, J. K. V., Markowitz, S. D., Kinzler, K. W. & Vogelstein, B. (1998) Nature 392, 300-303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bardelli A., Cahill, D. P., Lederer, G., Speicher, M. R., Kinzler, K. W., Vogelstein, B. & Lengauer, C. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 5770-5775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lengauer C., Kinzler, K. W. & Vogelstein, B. (1997) Nature 386, 623-627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bach S. P., Renehan, A. G. & Potten, C. S. (2000) Carcinogenesis 21, 469-476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lipkin M., Bell, B. & Shelrock, P. (1963) J. Clin. Invest. 42, 767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shorter R. G., Moertel, C. G. & Titus, J. L. (1964) Am. J. Dig. Dis. 9, 760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fearon E. R. & Vogelstein, B. (1990) Cell 61, 759-767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kinzler K. W. & Vogelstein, B., (1998) The Genetic Basis of Human Cancer (McGraw–Hill, Toronto).

- 23.Kaplan K. B., Burds, A. A., Swedlow, J. R., Bekir, S. S., Sorger, P. K. & Näthke, I. S. (2001) Nat. Cell Biol. 3, 429-432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fodde R., Kuipers, J., Rosenberg, C., Smits, R., Kielman, M., Gaspar, C., van Es, J. H., Breukel, C., Wiegant, J., Giles, R. H. & Clevers, H. (2001) Nat. Cell Biol. 3, 433-438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abdel-Rahman W. M., Katsura, K., Rens, W., Gorman, P. A., Sheer, D., Bicknell, D., Bodmer, W. F., Arends, M. J., Wyllie, A. H. & Edwards, P. A. W. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 2538-2543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Armitage P. & Doll, R. (1954) Br. J. Cancer 8, 1-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fisher J. C. (1958) Nature 181, 651-652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moolgavkar S. H. & Knudson, A. G. (1981) J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 66, 1037-1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mao J. H. & Wheldon, T. E. (1995) Math. Biosci. 129, 95-110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tomlinson I. P. M., Novelli, M. R. & Bodmer, W. F. (1996) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93, 14800-14803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yatabe Y., Tavare, S. & Shibata, D. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 10839-10844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Loeb L. A. (1998) Adv. Cancer Res. 72, 25-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Albertini R. J., Nicklas, J. A., O'Neill, J. P. & Robison, S. H. (1990) Annu. Rev. Genet. 24, 305-326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.de Nooij-Van Dalen A. G., Morolli, B., van der Keur, M., van der Marel, A., Lohman, P. H. & Giphart-Gassler, M. (2001) Genes Chromosomes Cancer 30, 323-335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grist S. A., McCarron, M., Kutlaca, A., Turner, D. R. & Morley, A. A. (1992) Mutat. Res. 266, 189-196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jackson A. L. & Loeb, L. A. (1998) Genetics 148, 1483-1490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]