Abstract

We describe a protocol for generating a potent cellular immune response against viral-infected cells, and demonstrate its efficacy and safety in a mouse model of human cancer associated with infection by a human papillomavirus (HPV). In the mouse model, the mouse tumor TC-1, which expresses the E7 oncoprotein from HPV-16, is used as a surrogate for human tumors infected with HPV-16. The antigen for the protocol is composed of the E7 oncoprotein conjugated to the Fc region of a mouse IgG1 Ig (E7-mFc). The mFc domain should bind to Fc receptors on dendritic cells, enhancing the processing and presentation of E7 peptides by dendritic cells to T cells, which mediate a cellular immune attack against tumors expressing E7. The E7-mFc antigen was encoded in a replication-incompetent adenoviral vector, called Ad(E7-mFc), for infection of the human kidney cell line 293. The infected 293 cells synthesize the E7-mFc antigen and also infectious Ad(E7-mFc) vector particles for ≈2 days, until the cells lyse and the vector particles are released. To test the protocol for immunization against formation of a TC-1 tumor, the mice first were injected s.c. with 293 cells infected with Ad(E7-mFc), followed by two challenges with TC-1 cells. The immunized mice remained healthy and tumor-free for the 6-month duration of the experiment, and the autopsies showed no toxicity. In the control mice immunized with 293 cells infected with an adenoviral vector that does not encode the E7-mFc antigen, the TC-1 tumor grew continuously and the mice had to be killed within 1 month. To test the protocol for immunotherapy, the mice first were injected with TC-1 cells, followed by s.c. injections of 293 cells infected with Ad(E7-mFc). Tumor growth was prevented or strongly retarded in these mice, in contrast to the continuous tumor growth in the controls. These results suggest that the protocol could be adapted for immunization against human cancers associated with an HPV infection, notably cervical cancer, and for immunotherapy to prevent recurrence of a tumor after surgery.

Infection by the human papillomavirus (HPV)-16 or HPV-18 is the probable cause of most cases of human cervical carcinoma, the second most frequent cancer in women worldwide (1, 2). Invasive cervical tumor cells express the HPV oncoproteins E6 and E7, which maintain the transformed state of the cells (3–7). Most vaccines for cervical cancer were designed to induce an immune response against E6 and/or E7. Anti-E7 vaccines that have been tested in animal models of human cervical cancer include E7 peptides, E7 protein, and a fusion protein of E7 with the HPV-L1 protein that forms empty HPV-like particles (8–13). The vaccines were synthesized ex vivo and administered as a purified antigen combined with an adjuvant, or were encoded in a DNA or viral vector for synthesis in vivo. Some of the vaccines are being tested in clinical trials. (Current cervical cancer trials are listed on the National Cancer Institute web site.)

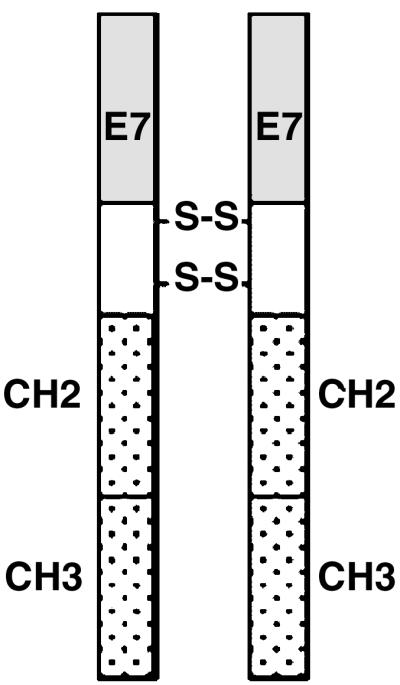

Here we describe a cancer vaccine in which the antigen is an E7-Fc fusion protein composed of two domains, the E7 protein of HPV-16 and the Fc region of an IgG1 Ig (Fig. 1). The Fc domain of the fusion protein should bind to Fc receptors on dendritic cells (14), activating efficient processing and presentation of E7 peptides to T cells, which can mediate a cellular immune attack against cells expressing E7. We developed an in vivo delivery system for an E7-Fc antigen, consisting of the human kidney line 293 infected with a replication-incompetent adenoviral vector encoding the antigen. The infected 293 cells synthesize the antigen and also provide in trans the components required to produce infectious vector particles. The efficacy and safety of the antigen and delivery system were tested in a mouse model for human tumors associated with an HPV infection. The model involves s.c. injection of the mouse tumor line TC-1, which contains a cDNA encoding the E7 protein of HPV-16 to generate a skin tumor that serves as a surrogate for a human tumor expressing E7, such as a human cervical carcinoma (10). For experiments in mice, the Fc domain of the antigen is derived from a mouse IgG1 Ig (E7-mFc antigen). The immunization protocol involves injecting 293 cells s.c. before injecting TC-1 cells, to prevent subsequent tumor development. The immunotherapy protocol involves injecting 293 cells shortly after injecting TC-1 cells, to prevent or retard the growth of an early-stage tumor. The results reported here demonstrate that the protocol is efficacious and safe when the 293 cells are injected either before or after injecting the TC-1 cells.

Fig 1.

Diagram of the E7-mFc fusion protein. E7, oncoprotein E7 from HPV-16; H, hinge region of a mouse IgG1 Ig with two disulfide bridges; CH2 and CH3, constant regions of a mouse IgG1 Ig.

Materials and Methods

Cell Lines.

The human kidney cell line 293 was purchased from American Type Culture Collection. The cells were grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS + 50 units/ml penicillin/streptomycin. The mouse lung tumor line TC-1, which was transduced to express the E7 oncogene of HPV-16, was provided by T. C. Wu (10). TC-1 cells were grown in RPMI medium 1640 supplemented with 10% FBS + 50 units/ml penicillin + 50 μg/ml streptomycin and 0.4 mg/ml G418.

Synthesis of cDNAs Encoding the E7-mFc Fusion Protein.

The cDNA encoding the E7 protein of HPV-16 with a mouse IgG1 leader sequence was synthesized by PCR, by using a plasmid carrying HPV-16 genes as the template, as follows.

The sequence of the 5′ primer containing the mouse IgG1 leader sequence was AACCCGAATTCATGGAAAGGCACTGGATCTTTCTCTTCCTGTTTTCAGTAACTGCAGGTGTCCACTCCATGCATGGAGATACA.

The sequence of the 3′ primer was AACCCGGATCCTGGTTTCTGAGAAC.

The E7 PCR product was ligated in-frame with a mFc cDNA in a pcDNA3.1 vector containing the mFc cDNA (15). The vector DNA was amplified in DH5α bacteria.

Construction and Amplification of the Ad(E7-mFc) Adenoviral Vector.

The adenoviral vector system consists of the shuttle vector pShuttle-CMV and the backbone vector pAdEasy-1 (16). The E7-mFc cDNA was excised from the pcDNA3.1 vector by digestion with HindIII and XbaI and ligated into the corresponding cloning sites of the pShuttle-CMV vector. The subsequent steps for constructing and purifying a recombinant adenoviral plasmid containing a cDNA insert are described elsewhere (17). The purified recombinant adenoviral plasmids were transfected into 293 cells to generate infectious adenovirus containing the E7-mFc cDNA. The adenoviruses were purified by centrifugation in CsCl (16), dialyzed against PBS + 5% glycerol and 1 mM MgCl2, and stored at −70°C. The adenovirus titer was calculated as follows: 1.0 optical density unit at 260 nm = 1 × 1012 adenovirus particles.

Synthesis of E7-mFc Protein in 293 Cells Infected with the Ad(E7-mFc) Vector.

A 293 culture grown to ≈80% confluence in a 75-cm2 flask was infected with the Ad(E7-mFc) vector, and the cells were harvested in SDS lysis buffer (20 mM Tris, pH 7.5/150 mM NaCl/10 mM DTT/1 mM PMSF/10 μg of aprotinin per ml/10 μg of leupeptin/ml/5 μg of pepstatin/ml). A sample of the cell lysate was fractionated by SDS/PAGE in a 10% gel and electroblotted onto a nitrocellulose membrane. The membrane was blocked, equilibrated with an anti-HPV-16 E7 monoclonal antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), washed, and equilibrated with an anti-mouse antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase for 1 h at room temperature. The signal was detected by enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham Pharmacia).

Infection of 293 Cells with the Ad(E7-mFc) Vector for Injection into Mice.

A 150-cm2 culture dish was seeded with 5 × 106 293 cells and kept at 37°C in a CO2 incubator for 24 h, and the cells were infected with 1 × 107 to 2 × 107 vector particles. The infected cells were collected after 1–2 days for s.c. injection into one mouse.

Immunization and Immunotherapy Protocols for TC-1 Tumors in a Mouse Model.

C57BL/6 mice (4- to 6-week-old females from Taconic Farms) were used for all experiments.

(i) For immunization, the mice were first injected s.c. in the left rear flank with purified Ad(E7-mFc) vector or with 293 cells infected with the Ad(E7-mFc) vector; a total of three injections were given at intervals of 5 days. One week after the third injection, the mice were challenged by a s.c. injection in the right rear flank of 5 × 104 TC-1 cells. (ii) For immunotherapy, the mice were first injected s.c. in the left rear flank with 5 × 104 TC-1 cells, followed by injections of 293 cells 3 or 7 days later; the 293 cells were infected with the Ad(E7-mFc) vector or with an adenoviral vector lacking the insert as a control. The dimensions of the tumor at the site of injection of TC-1 cells were measured every second day in two perpendicular directions with a caliper, and the volume of the tumor was estimated by the formula (S)2(L)/2; S is the shorter dimension and L is the longer dimension of the tumor.

Lysis of Cultured TC-1 Cells Mediated by Activated Spleen Cells from Immunized Mice.

Mice were immunized by s.c. injections of 293 cells infected with a vector encoding the E7-mFc protein or the control vector on days 0, 5, and 10, as described above. Splenocytes were isolated 7 days after the last injection, and single-cell suspensions were prepared by passage through a 40-μm nylon sieve (Falcon). The cells were washed twice with PBS and red blood cells were removed by incubating with NH4Cl/KCl buffer for 5 min at 4°C followed by two washes in PBS. The splenocytes were added first to irradiated TC-1 cells (8,000 rads from a 60Co source) and cocultured for 3 days in RPMI medium 1640 supplemented with 10% FBS, 2 mM l-glutamine, 20 units of penicillin per ml, 20 μg of streptomycin per ml, 1% MEM nonessential amino acids, 1% MEM sodium pyruvate, and 5 × 10−5 M mercaptoethanol. The splenocytes were then transferred to a culture dish containing 5 × 105 viable TC-1 cells and incubated for the indicated times. Lysis of the TC-1 cells was monitored microscopically.

Results

Synthesis of the E7-Fc Fusion Protein by 293 Cells Infected with the Ad(E7-mFc) Adenoviral Vector.

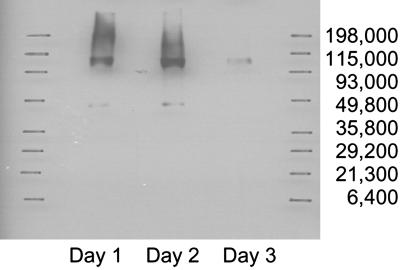

The E7-mFc molecule is a fusion protein composed of the E7 oncoprotein and the Fc region of a mouse IgG1 Ig. The molecule is a homodimer with the monomers linked by disulfide bridges in the hinge region of the Fc region (Fig. 1). 293 cells were infected with the Ad(E7-mFc) vector and tested by a Western assay for synthesis of E7-mFc protein, with an anti-E7 antibody to detect the protein (Fig. 2). The Western assay shows two bands, an intense band at ≈95 kDa corresponding to the homodimeric molecule and a much weaker band corresponding to the monomeric molecule, which apparently results from incomplete formation of the interchain disulfide bridges. Synthesis of the E7-mFc protein continued for 2 days and almost completely stopped by the third day, presumably because of cell lysis associated with the release of Ad(E7-mFc) vector particles produced concomitantly with the E7-mFc protein.

Fig 2.

Synthesis of the E7-mFc fusion protein in 293 cells infected with the Ad(E7-mFc) adenoviral vector. The 293 cells were fractionated by PAGE and the protein bands were transferred to a membrane. The E7-mFc bands were detected by incubating the membrane first with an anti-mouse Fc antibody followed by the ECL system (Amersham Pharmacia). The cells were harvested on days 1, 2, or 3 after infection with the vector.

The E7-mFc Protein Generates Long-Term Immunity Against Formation of TC-1 Tumors in Mice.

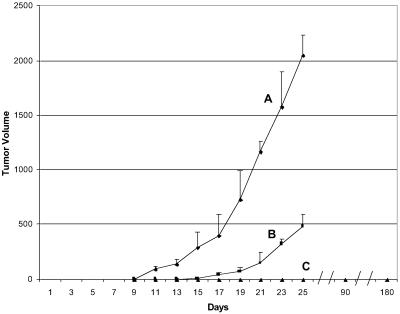

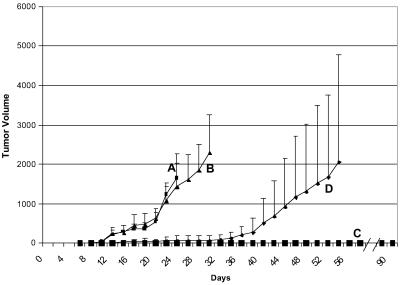

We tested two methods for delivering the E7-mFc protein, either by s.c. injections of purified Ad(E7-mFc) vector particles or of 293 cells infected with the Ad(E7-mFc) vector (Fig. 3). The infected 293 cells produce infectious Ad(E7-mFc) particles and also E7-mFc protein. The mice first received three s.c. injections of the purified vector particles (curve B) or of 293 cells infected with the Ad(E7-mFc) vector (curve C) or of 293 cells infected with a control vector (curve A), before being challenged 1 week later with TC-1 cells; some of the mice from curve C were challenged again 12 weeks later. The results show that the vector particles retarded but did not prevent tumor growth, in contrast to the 293 cells infected with the Ad(E7-mFc) vector, which completely prevented tumor development even after the second challenge with TC-1 cells. The vector particles also were injected intravenously and showed a similar retardation effect on tumor growth as did the s.c. injected vector particles (data not shown). The immunity generated by the infected 293 cells persisted for the duration of the experiment, which was terminated after 6 months. The mice immunized with the Ad(E7-mFc)-infected 293 cells appeared healthy and tumor-free at the end of the experiment, and no evidence of toxicity existed on careful examination of the mice during autopsy.

Fig 3.

Immunization of mice against formation of a TC-1 tumor. Comparison of purified Ad(E7-mFc) vector particles with 293 cells infected with the Ad(E7-mFc) vector. Curve A (control): Five mice received three s.c. injections of 1 × 1011 particles per injection of an adenoviral vector that did not encode E7-mFc. Curve B: Five mice received three i.v. injections of 1 × 1011 particles per injection of the Ad(E7-mFc) vector. Curve C: Ten mice received three s.c. injections of 5 × 106 293 cells infected with the Ad(E7-mFc) vector. The three s.c. injections were administered at 5-day intervals, and 1 week after the last injection all of the mice were challenged by a s.c. injection of 5 × 104 TC-1 cells; five mice from curve C were challenged again 12 weeks after the first challenge. Tumor growth on the skin surface was monitored by measurements with a caliper. Each point is the average value for the mice in each curve, and the vertical line is the standard deviation. No tumor was detected in any of the mice from curve C throughout the experiment. All of the mice from curve C were autopsied and the organs and tissues were examined. No evidence of toxicity was detected in any of the mice.

s.c. Injection of Adenovirus-Infected 293 Cells Results in Secondary Infection of Skin Cells by Adenovirus Produced in the 293 Cells.

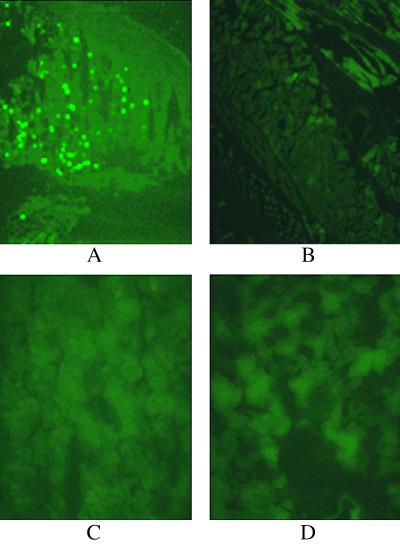

The 293 cells were infected with an adenoviral vector encoding the GFP, and the cells were injected s.c. into mice. The mice were killed 3 days later, and frozen sections of skin from the injected site and from a distant skin site, and also from the kidney and liver, were examined in a fluorescent microscope for cells expressing GFP (Fig. 4). GFP expression was detected only in skin cells from the injected site.

Fig 4.

Biodistribution of the adenoviral vector in mice after s.c. injection of 293 cells infected with the vector. The 293 cells were infected with an adenoviral vector labeled with GFP cDNA inserted into the vector genome, and 5 × 106 infected cells were injected s.c. into the left rear flank of the mice. After 3 days, the mice were killed and frozen sections were prepared from the following tissues: (A) skin from the injected site; (B) skin from the right rear flank that was not injected; (C) liver; (D) kidney. The sections were photographed with a fluorescent microscope at ×200 magnification.

The Immunity Generated by the E7-mFc Protein Against TC-1 Tumors Involves Activation of a Cytolytic Response Against TC-1 Cells Mediated by Spleen Cells.

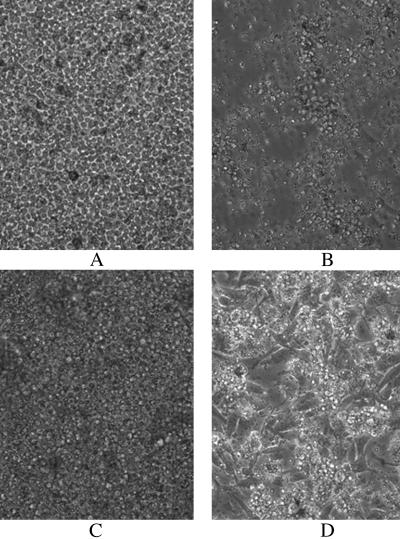

Splenocytes were isolated from immunized and control mice 5 days after a third s.c. injection of 293 cells infected with the Ad(E7-Fc) vector or a control vector (see Fig. 3). The splenocytes were cocultured first with irradiated TC-1 cells and then with viable TC-1 cells. After 6 days of coculture with the splenocytes from the immunized mice, the viable TC-1 cells were almost completely lysed, in contrast to the dense growth of TC-1 cells that were cocultured with splenocytes from the control mice (Fig. 5).

Fig 5.

Cytolysis of TC-1 tumor cells by spleen cells from immunized mice. Splenocytes were isolated 7 days after the mice received three s.c. injections of 293 cells infected with the Ad(E7-mFc) vector or with a control adenoviral vector, as described in Fig. 3. An aliquot of 1 × 107 splenocytes was incubated for 3 days with 5 × 105 irradiated TC-1 cells (8,000 rads from a 60Co source), and the splenocytes were then transferred to a culture dish containing 5 × 105 viable TC-1 cells. (A and B) Splenocytes from the control mice at 2 and 6 days, respectively, after coculture with viable TC-1 cells. (C and D) Splenocytes from the immunized mice at 2 and 6 days, respectively, after coculture with viable TC-1 cells. After 2 days the splenocytes form a layer of small round cells covering the attached TC-1 cells and then aggregate to form cell clusters after 6 days. Note that the TC-1 cells have formed a dense attached layer in B and have almost completely disappeared in D, indicating that splenocytes from the immunized mice induce efficient lysis of the TC-1 cells. The cultures were photographed at ×200 magnification.

The E7-mFc Protein Shows Therapeutic Efficacy Against Early-Stage TC-1 Tumors.

Tumor growth was initiated by s.c. injection of TC-1 cells into the mice 3 or 7 days before treating the mice by three s.c. injections of 293 cells infected with the Ad(E7-mFc) vector (Fig. 6). A palpable tumor had formed in the mice by 7 days after injection of the TC-1 cells. When the injections of the 293 cells were started 3 days after injection of the TC-1 cells, development of a TC-1 tumor was prevented in all five mice. When the injections of 293 cells were started 7 days after injection of the TC-1 cells, tumor development was prevented in two mice and strongly retarded in the remaining three mice.

Fig 6.

Immunotherapy of early-stage TC-1 tumors in mice. The mice were injected s.c. with 5 × 104 TC-1 cells, followed by three s.c. injections of 293 cells infected with the Ad(E7-Fc) vector or a control vector starting 3 or 7 days later. A palpable tumor was detected in the mice at 7 days. (A and B) Injection of 293 cells infected with the control vector starting 3 or 7 days, respectively, after injection of TC-1 cells. (C and D) Injection of 293 cells infected with the Ad(E7-Fc) vector starting 3 or 7 days, respectively, after injection of TC-1 cells. Each experiment involved five mice. No tumor was detected in any of the mice in C or in two of the mice in D; the remaining three mice in D had tumors that grew at a slower rate than the control tumors.

Discussion

Several human cancers, notably cervical cancer, are associated with, and probably caused by, an HPV infection. The tumor cells express the HPV oncoproteins E6 and E7, which are potential targets for an immune attack against the tumor cells. Various immunization and immunotherapy protocols that target the E6 and/or E7 proteins have been tested in a mouse model of HPV-induced cancers (8–13), and some of the protocols are being tested in clinical trials for cervical cancer. (Current cervical cancer trials are listed on the National Cancer Institute web site.) At the present time, none of the protocols has been adopted for general use in preventing or treating cervical cancer, which remains a major threat to women worldwide.

The protocol described here has two unique features. One is the antigen, and the other is the delivery system for in vivo synthesis of the antigen. The antigen is an E7-mFc fusion protein composed of the E7 oncoprotein from HPV-16 conjugated to the Fc region of a mouse IgG1 Ig. The rationale for using this antigen is that the Fc region should bind to Fc receptors on dendritic cells (14), enhancing the capacity of the dendritic cells to process and present E7 peptides to T cells. The responding T cells efficiently target for cytolysis tumor cells expressing E7, such as the mouseTC-1 cells used in the mouse model of HPV-induced cancers (see Fig. 5).

The in vivo delivery system involves s.c. injections of 293 cells infected with the Ad(E7-mFc) vector, a replication-incompetent adenoviral vector encoding the E7-mFc antigen. This delivery system has several features that enhance the efficacy and safety of the protocol, as follows. (i) The skin is a prime site for interaction between the E7-mFc antigen and Langerhans dendritic cells, which is the initial step in the induction of a cellular immune response against tumor cells that express E7. (ii) 293 cells infected with the Ad(E7-mFc) vector produce both the E7-Fc protein and infectious vector particles. The vector particles infect skin cells at the injection site of the 293 cells (see Fig. 4), generating additional producer cells for the E7-mFc antigen. (iii) 293 cells infected with the Ad(E7-mFc) vector do not proliferate and lyse after 2 days when the vector particles are released, and therefore should not pose a toxicity risk.

We demonstrated in this report that s.c. injections of mice with 293 cells infected by the Ad(E7-mFc) vector resulted in complete long-term immunity against later challenges with TC-1 tumor cells that express E7 (see Fig. 3). The challenged mice appeared healthy and free of tumor when the experiment was terminated 180 days after immunization, and no toxicity was detected by autopsy. In the control mice that were not immunized, the TC-1 tumor grew continuously, requiring the mice to be killed within 30 days. The protocol also was efficacious for immunotherapy against early-stage TC-1 tumors (see Fig. 6). These findings suggest that the protocol could be adapted for vaccination against HPV-induced human cancers, particularly cervical cancer, and also as follow-up immunotherapy for such cancer patients who have had surgery to remove a tumor but remain at high risk of suffering a recurrence. The E7-Fc antigen for human use would contain a human Fc domain in place of a mouse Fc domain.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. Zhiwei Hu for assistance with the construction of the E7-mFc cDNA and the Ad(E7-mFc) vector and to Dr. Bingguan Chen for assistance in performing the tests reported in Fig. 5. The mouse tumor line TC-1 was provided by Dr. T. C. Wu. The autopsies and examinations of the mice were done by Gordon Terwilliger in the Comparative Medicine Laboratory at Yale University School of Medicine. Support was provided by generous contributions from private donors to a Gift Fund for the laboratory of A.G.

Abbreviations

HPV, human papillomavirus

References

- 1.Krul E. J., Van De Vijver, M. J., Schuuring, E., Van Kanten, R. W., Peters, A. A. & Fleuren, G. J. (1999) Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 9, 206-211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bosch F. X., Manos, M. M., Munoz, N., Sherman, M., Jansen, A. M., Peto, J., Schiffman, M. H., Moreno, V., Kurman, R. & Shah, K. V. (1995) J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 87, 796-802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Farthing A. J. & Vousden, K. H. (1994) Trends Microbiol. 2, 170-174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Von Knebel Doeberitz M., Rittmuller, C., Aengeneyndt, F., Jansen-Durr, P. & Spitkovsky, D. (1994) J. Virol. 68, 2811-2821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hwang E., Riese, D. R., Settleman, J., Nilson, L., Honig, J., Flynn, S. & DiMaio, D. (1993) J. Virol. 67, 3720-3729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goodwin E. & DiMaio, D. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97, 12513-12518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.zur Hausen H. (2002) Nat. Rev. Cancer 2, 342-350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Da Silva D. M., Eiben, G. L., Fausch, S. C., Wakabayashi, M. T., Rudolf, M. P., Velders, M. P. & Kast, W. M. (2001) J. Cell Physiol. 186, 169-182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zwaveling S., Ferreira Mota, S. C., Nouta, J., Johnson, M., Lipford, G. B., Offringa, R., van der Burg, S. H. & Melief, C. J. (2002) J. Immunol. 169, 350-358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lin K. Y., Guarnieri, F. G., Staveley-O'Carroll, K. F., Levitsky, H. I., August, J. T., Pardoll, D. M. & Wu, T. C. (1996) Cancer Res. 56, 21-26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen L., Thomas, E. K., Hu, S.-L., Hellstrom, I. & Hellstrom, K. E. (1991) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88, 110-114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.He Z., Wlazlo, A. P., Kowalczyk, D. W., Cheng, J., Xiang, Z. Q., Giles-Davis, W. & Ertl, H. C. (2000) Virology 270, 146-161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Daemen T., Regts, J., Holtrop, M. & Wilschut, J. (2002) Gene Ther. 9, 85-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Regnault A., Lankar, D., Lacabanne, V., Rodriguez, A., Thery, C., Rescigno, M., Saito, T., Verbeek, S., Bonnerot, C., Ricciardi-Castagnoli, P. & Amigorena, S. (1999) J. Exp. Med. 189, 371-380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang B., Chen, Y. B., Ayalon, O., Bender, J. & Garen, A. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 1627-1632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.He T. C., Zhou, S., da Costa, L. T., Yu, J., Kinzler, K. W. & Vogelstein, B. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 2509-2514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hu Z., Sun, Y. & Garen, A. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 8161-8166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]