Abstract

CK2 (protein kinase CK2) is known to phosphorylate eIF2 (eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2) in vitro; however, its implication in this process in living cells has remained to be confirmed. The combined use of chemical inhibitors (emodin and apigenin) of CK2 together with transfection experiments with the wild-type of the K68A kinase-dead mutant form of CK2α evidenced the direct involvement of this protein kinase in eIF2β phosphorylation in cultured HeLa cells. Transfection of HeLa cells with human wild-type eIF2β or its phosphorylation site mutants showed Ser2 as the main site for constitutive eIF2β phosphorylation, whereas phosphorylation at Ser67 seems more restricted. In vitro phosphorylation of eIF2β also pointed to Ser2 as a preferred site for CK2 phosphorylation. Overexpression of the eIF2β S2/67A mutant slowed down the rate of protein synthesis stimulated by serum, although less markedly than the overexpression of the Δ2–138 N-terminal-truncated form of eIF2β (eIF2β-CT). Mutation at Ser2 and Ser67 did not affect eIF2β integrating into the eIF2 trimer or being able to complex with eIF5 and CK2α. The eIF2β-CT form was also incorporated into the eIF2 trimer but did not bind to eIF5. Overexpression of eIF2β slightly decreased HeLa cell viability, an effect that was more evident when overexpressing the eIF2β S2/67A mutant. Cell death was particularly marked when overexpressing the eIF2β-CT form, being detectable at doses where eIF2β and eIF2β S2/67A were ineffective. These results suggest that Ser2 and Ser67 contribute to the important role of the N-terminal region of eIF2β for its function in mammals.

Keywords: eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2 (eIF2), HeLa cells, human eIF2β subunit, protein interaction, protein kinase CK2, protein phosphorylation

Abbreviations: CK2, protein kinase CK2; DMEM, Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium; eIF, eukaryotic translation initiation factor; FBS, fetal bovine serum; HA, haemagglutinin; hr, human recombinant; Met-tRNAiMet, initiator methionine tRNA; Ni-NTA, Ni2+-nitrilotriacetate; PKC, protein kinase C; PP2A, protein phosphatase 2A; PP2Ac, catalytic subunit of the PP2A

INTRODUCTION

Translation initiation in eukaryotes requires the participation of multiple protein components that must form transient, specific complexes following a fixed and precise sequence [1,2]. Some of the eIFs (eukaryotic translation initiation factors), such as eIF2, intervene at different stages of translation initiation, due to the presence in its structures of different domains, each one involved in specific functions. The conventional form of eIF2 is a trimer made of one copy of each of the three different subunits (eIF2α, eIF2β and eIF2γ). Of these subunits, eIF2α is well known to play a key regulatory role in translation initiation. Phosphorylation on its Ser51 by different eIF2α kinases [1–4] leads to it binding tightly to the non-catalytic subunits of eIF2B, sequestering it in an inactive complex. eIF2B is the GEF (guanine nucleotide-exchange factor) protein that catalyses the GDP/GTP exchange in eIF2, a crucial event that allows eIF2 to participate in a new round of translation initiation. The eIF2γ subunit is the central component in assembling the eIF2 trimer, bridging between eIF2α and eIF2β. It contributes to the G-protein-like properties of eIF2 and together with the eIF2β subunit contributes to Met-tRNAiMet (initiator methionine transfer RNA) binding [5,6].

Previous studies based on genetic approaches with yeast or using recombinant mammalian proteins have shown that eIF2β subunit is responsible for many of the interactive properties characteristic of eIF2. The eIF2β subunit binds to mRNA [7] as well as to the catalytic subunit of eIF2B (eIF2Bϵ) [8,9] and to eIF5 (which acts as a GTPase-activating protein) [9,10]. Moreover, eIF2β binds directly to TIF32 (transcriptional intermediary factor 32)/eIF3a [11] and eIF2β binding to eIF5 potentiates the association of the latter with Nip1/eIF3c, which helps to integrate the ternary complex into the multifactor complex [12]. In addition, eIF2β binds to the adaptor protein Nck-1 [13] and this binding prevents the phosphorylation of eIF2α and the subsequent arrest of translation in response to endoplasmic reticulum stress [14]. We have recently shown that eIF2β also binds to CK2 (protein kinase CK2), an enzyme known to phosphorylate in vitro different eIFs, including eIF2, and ribosomal proteins [15], and that the binding of eIF2β to the free catalytic subunit of CK2 (CK2α) inhibits its activity in protein substrates [16].

The functional and structural analyses of eIF2β have evidenced that it contains three different regions: the N-terminal, the central and the C-terminal regions [17,18]. The central region contains the binding site to eIF2γ [19], whereas the C-terminal region contains a zinc-finger motif that contributes to mRNA binding and start-site selection during the scanning process in yeast [20]. The central/C-terminal regions also contain the binding sites for CK2, whereas the phosphorylation sites for this protein kinase are located in the N-terminal region. The presence of three lysine blocks and in vitro phosphorylation sites for protein kinase CK2 and PKC (protein kinase C) are characteristic of the N-terminal region of mammalian eIF2β [21]. The lysine blocks are conserved in yeast and participate in binding to eIF5, eIF2Bϵ and mRNA [7,9]. In yeast, deletion of the lysine blocks compromises cell growth, which points to an important role for this structural feature [7]. Whether these cell growth effects are also exerted on mammalian cells has not yet been explored.

Phosphorylation of eIF2β in vitro and in vivo has been known for almost three decades [22,23]. The sites phosphorylated in vitro on mammalian eIF2β have been mapped at Ser2, Ser67 (both targeted by CK2), Ser13 (targeted by PKC) and Ser218 [targeted by PKA (protein kinase A)] [21]. eIF2β is also a substrate for DNA-PK (DNA protein kinase) [24], although the phosphorylation site(s) for this kinase have not been identified yet. The studies on the phosphorylation of eIF2β in mammalian cells have shown that it varies under different conditions such as heat shock [25], serum deprivation [26], diabetes [27] and birth [28]. Yeast eIF2 is also a phosphoprotein, but in this case phosphorylation by CK2 in vitro takes place on its eIF2α subunit but not on its eIF2β subunit [29,30]. Specific phosphorylation by CK2 at the eIF2α subunit has also been reported for eIF2 from Artemia salina [31] and sea urchin [32].

Initial studies on the functional consequences of mammalian eIF2β phosphorylation for protein synthesis showed that it did not affect the ability of eIF2 to form the ternary complex with GTP and Met-tRNAiMet [33]. However, later on, it was observed that phosphorylation of eIF2β by CK2 decreases the affinity of GDP binding to eIF2 [34]. The mutagenic approach has proven to be very useful for defining Ser712/Ser713 as the constitutive CK2 phosphorylation sites in the eIF2Bϵ subunit and for determining that it is required for the interaction with eIF2 in vivo [35], which provides an answer to the discrepancy in the results obtained in previous studies using endogenous phosphorylated eIF2B [35–37].

In the present work, we studied the phosphorylation of human eIF2β in vivo and the relevance of the main phosphorylation sites and of the entire N-terminal domain of eIF2β in its interaction with some partners, in protein synthesis and in cell viability. Moreover, the role of CK2 in the basal phosphorylation of this subunit has been explored by using chemical inhibitors and a CK2 mutant that directly alters CK2 activity within the cell [38]. The results provide strong support for CK2 being involved in the basal phosphorylation of eIF2β. They show that almost all of the cellular eIF2β is phosphorylated in Ser2, whereas phosphorylation in Ser67 is more restricted and that mutation at these sites alters eIF2β properties, although less drastically than the truncation of the entire N-terminal domain.

EXPERIMENTAL

Reagents and antibodies

Apigenin, emodin and anti-His6 antibody were obtained from Sigma, anti-eIF2α and the catalytic subunit of the PP2A (protein phosphatase 2A) phosphatase were from Cell Signaling Technology, anti-CK2α and anti-eIF5 were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology and anti-eIF2α was from Cell Signaling Technology. The anti-eIF2β antibody was raised in rabbits immunized with the recombinant protein, and the immunoglobulin fraction was obtained from sera by Protein A–agarose chromatography (Amersham Biosciences). Anti-eIF2γ antibody was raised in rabbits against the human eIF2γ peptide VGQEIEVRPGIVSK. Anti-HA (haemagglutinin; 12CA5) antibody was from Roche. [γ-32P]ATP and [32P]Pi were from Amersham Biosciences.

Plasmids, protein expression and purification

The catalytic (CK2α) and regulatory (CK2β) subunits of human CK2, and the wild-type and mutated forms of the β-subunit of human eukaryotic initiation factor 2 cloned in pQE-30 vector were expressed in Escherichia coli and purified as His6-tagged fusion proteins by Ni-NTA (Ni2+-nitrilotriacetate)–agarose chromatography as described previously [16]. Amino acid substitutions were made by PCR oligonucleotide site-directed mutagenesis with the Stratagene kit according to the manufacturer's instructions. In all cases, mutations were confirmed by DNA sequencing. pCMV-HA or pCMV mammalian expression vectors (ClonTech) encoding N-terminal HA-tagged eIF2β and CK2α respectively were made as described previously by subcloning from the pQE-30 vectors (Qiagen) [16].

Cell culture and transfection

HeLa cells were grown in DMEM (Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium) with 4.5 g/l glucose supplemented with 10% (v/v) FBS (fetal bovine serum). Incubation was at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. Cells were washed twice with cold PBS and lysed for 15 min on ice with lysis buffer A (50 mM Tris/HCl, pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 0.1% Nonidet P40, 50 mM β-glycerolphosphate, 2 mM PPi, 25 mM NaF, 1 mM Na3VO4, 1 mM PMSF and 1 μg/ml each of leupeptin, pepstatin, benzamidine and aprotinin). Lysates were centrifuged at 12000 g for 30 min at 4 °C in an Eppendorf microfuge and supernatants were used for the assays. For cell transfection, cells were seeded at 0.2×106 cells/ml and on the next day transfected with Lipofectamine™ Plus (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. After 3 h, the complete medium was re-established overnight and cells were lysed as described above.

Immunoprecipitation

For transfected HA–eIF2β, protein G–Sepharose (10 μl), equilibrated with lysis buffer A, was incubated with 4 μg of anti-HA antibody. HeLa cell extract protein (±500 μg) was added and incubated for 2 h at 4 °C on shaking. The immunocomplexes were washed twice with lysis buffer A plus 0.5 M NaCl and once with lysis buffer A. Proteins attached to the beads were eluted with SDS/PAGE sample buffer [0.5 M Sucrose, 10% (w/v) SDS, 300 mM Tris/HCl, 10 mM EDTA, 250 mM DTT (dithiothreitol) and 0.05% (w/v) Bromophenol Blue], subjected to SDS/PAGE, transferred on to PVDF membranes and probed with the indicated antibodies or subjected to autoradiography as indicated.

Pull-down assay

His6-tagged eIF2β, eIF2β-NT (1–137) or eIF2β-CT (138–333) (1 μg each) was mixed with 500 μg of HeLa cell extract, previously precleared with Ni-NTA–agarose (1:1; 20 μl) (Qiagen) for 1 h at 4 °C in lysis buffer A. A slurry of Ni-NTA–agarose (1:1; 20 μl) was added and left for 1 h at 4 °C under gentle shaking. Samples were centrifuged at 12000 g for 5 min at 4 °C in an Eppendorf microfuge to sediment the His6-tagged proteins/Ni-NTA-agarose–complexes. Beads were washed with lysis buffer A three times and proteins were eluted with SDS/PAGE sample buffer and subjected to SDS/PAGE, transferred on to PVDF membranes and probed against indicated antibodies.

[32P]Pi cell labelling

HeLa cells were grown as described previously and maintained in phosphate-free medium for 1 h. Cells were then grown in the presence of 0.5 mCi of [32P]Pi for 4 h. Where indicated, CK2 inhibitors apigenin (40 μM) or emodin (40 μM) were added to the assay during the labelling time. Cells were lysed with extraction buffer [50 mM Tris/HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 25 mM NaF, 1 mM Na3VO4 and 1 μg/ml each of aprotinin, pepstatin, leupeptin and benzamidine] and proteins were immunoprecipitated as described before. Samples were loaded onto SDS/PAGE, transferred on to PVDF membranes and subjected to autoradiography. A sample of the cell extract was probed for anti-HA antibody to ensure equal amounts of transfected protein into the assay.

[35S]Methionine/cysteine cell labelling

For protein synthesis measurements, HeLa cells were serum-starved with DMEM containing 0.5% FBS. After 24 h, cells were maintained in DMEM containing 0.5% dialysed FBS lacking methionine/cysteine for 1 h, and labelling was carried out by addition of 10% dialysed FBS containing [35S]methionine/cysteine (12.5 μCi/ml) at the indicated times. Cells were lysed as described above and protein was precipitated with 12% (w/v) ice-cold trichloroacetic acid containing 10 mM methionine/cysteine. Precipitated protein was washed twice with 5% ice-cold trichloroacetic acid and resuspended in 50 mM Tris/HCl (pH 7.5), 2% (v/v) Nonidet P40 and 1% SDS. Samples were boiled for 5 min at 100 °C and spotted in triplicate on 3MM filters. The filters were washed three times with 10% trichloroacetic acid, once with acetone, air dried and subjected to liquid scintillation.

Phospho amino acid analysis

Phospho amino acid analyses of human recombinant eIF2β (His6–eIF2β) phosphorylated by CK2 or in vivo phosphorylated and immunoprecipitated eIF2β (HA–eIF2β) were performed using one-dimensional analysis. The PVDF membranes containing the radiolabelled eIF2β band (5000 c.p.m.) were located by autoradiography, excised and transferred to a microcentrifuge tube. Protein was then hydrolysed in 0.2 ml of 6 M HCl for 1 h at 110 °C. The sample was centrifuged, and the supernatant was freeze-dried and resuspended in 10 μl of a mixture of phosphoserine, phosphothreonine and phosphotyrosine (1 mg/ml each). The samples were then spotted on a thin-layer cellulose plate and subjected to electrophoresis at 1100 V for 40 min in pyridine acetate buffer (pH 3.5) (water/acetic acid/pyridine, 945:50:5, by vol.) in a water-cooled system. The plate was dried and sprayed with acetone plus 1% (w/v) ninhydrin to localize the phospho amino acid standards. 32P-labelled amino acids on the dried plates were detected by autoradiography.

CK2 activity assay

HeLa cell extracts were lysed after treatments as described above and 5 μg of cell extract protein was used to phosphorylate 0.2 mM specific CK2 peptide (RRRAADSDDDDD) in the presence of 125 μM [γ-32P]ATP and kinase buffer (50 mM Tris/HCl, pH 7.5, 1.5 mM EGTA, 25 mM MgCl2, 10 mM sodium β-glycerolphosphate and 3 mM DTT) for 30 min at 30 °C. The samples were spotted on P81 papers, washed five times with 0.5% orthophosphoric acid, once with acetone and air dried. Radioactivity was quantified in a scintillation counter.

Phosphorylation of eIF2β by CK2 in vitro

Phosphorylation of wild-type and mutant His6–eIF2β forms (0.5 μg each) was carried out for 30 min at 30 °C as described previously [16] in a medium containing 2 pmol of His6–CK2 holoenzyme (reconstituted by mixing His6–CK2α and His6–CK2β at a 1:1 molar ratio) and 100 μM [γ-32P]ATP. The reactions were stopped by adding SDS/PAGE sample buffer and boiling, followed by SDS/PAGE and autoradiography. Coomassie Blue staining of the gel was performed to ensure equal amounts of protein in the assay. For phosphatase treatments, HA–eIF2β was immunoprecipitated and the immunocomplex was washed twice with phosphatase buffer (50 mM Tris/HCl, pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl and 1 mM MgCl2). Then 2 units of PP2Ac (catalytic subunit of PP2A) was added in a final volume of 35 μl and incubated for 30 min at 37 °C. The immunocomplexes were centrifuged, washed three times with kinase buffer and subjected to CK2 phosphorylation as described above. Samples were loaded on to SDS/10% polyacrylamide gels and subjected to autoradiography.

Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis

HeLa cell extracts were precipitated with 10% ice-cold trichloro-aceteic acid for 30 min, centrifuged and washed with 100 mM ammonium acetate in methanol. Pellets were resuspended in two-dimensional buffer (2.5% Nonidet P40, 8.5 M urea, 0.8% ampholites and 100 mM DTT). For the first dimension, samples were loaded on Immobiline dry strips (pH 4–7) on a Multiphor II System (LKB®) and ran overnight at 1000 V. For the second dimension, strips were equilibrated with 50 mM Tris/HCl (pH 8.8), 8.5 M urea, 30% (v/v) glycerol and 2% (w/v) SDS for 30 min and applied on a SDS/polyacrylamide gel. After electrophoresis, samples were transferred on to PVDF membranes and developed with the indicated antibodies.

RESULTS

Overexpression of eIF2β leads to its phosphorylation at some but not all of its potential CK2 targeted sites

CK2 has been considered to be involved in the basal phosphorylation of eIF2β from rabbit reticulocytes [21]. We decided to study this point in detail in HeLa cells by transfecting human eIF2β carrying the HA tag.

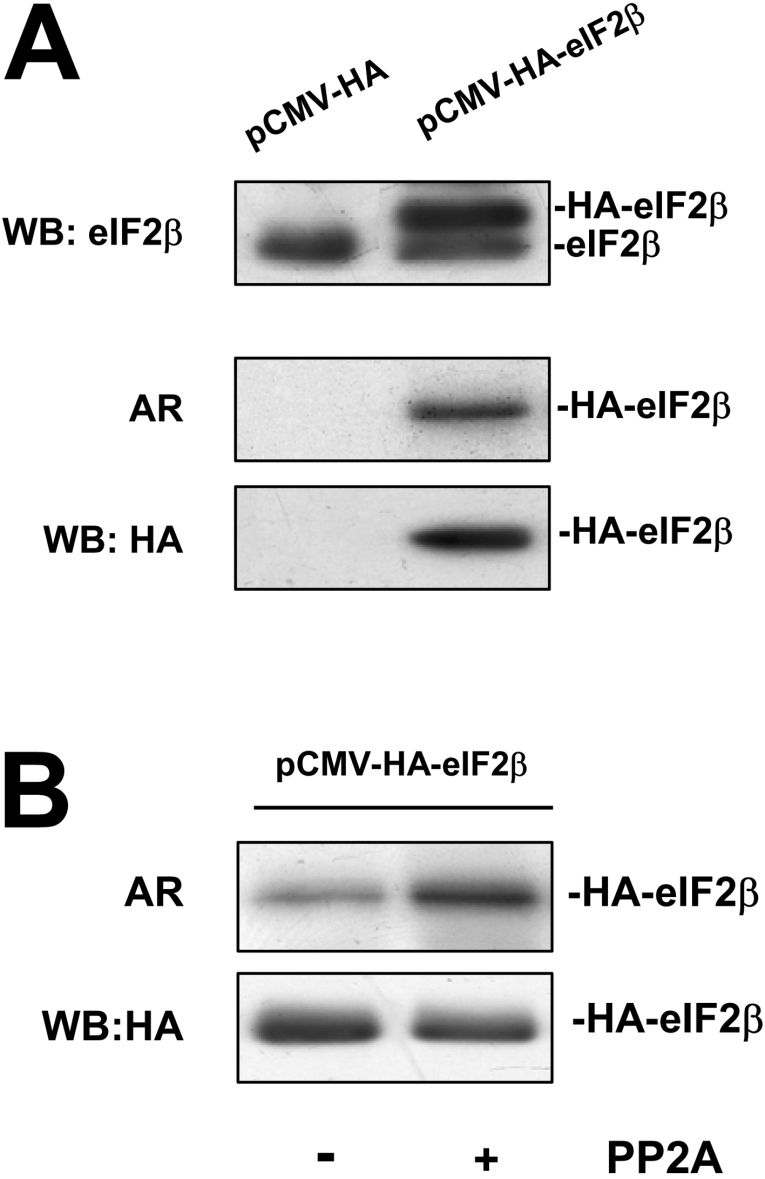

Transfection of HeLa cells allowed the expression of HA–eIF2β to values 2–3-fold above those of the endogenous eIF2β (Figure 1A). The HA–eIF2β form was recognized by the anti-HA and the anti-eIF2β antibodies. It migrated slightly above the endogenous eIF2β, as expected due to the presence of the HA tag. Moreover, the overexpressed HA–eIF2β was phosphorylated in vivo and immunoprecipitated with the anti-HA antibodies.

Figure 1. HA–eIF2β is constitutively phosphorylated in HeLa cells.

(A) HeLa cells were transfected with either pCMV-HA or pCMV-HA-eIF2β. Cell lysates were analysed by Western blotting with anti-eIF2β antibody. In a parallel experiment, HeLa cells were labelled with [32P]Pi and cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-HA antibody and subjected to SDS/PAGE followed by autoradiography (AR) and Western blotting against anti-HA antibody. (B) HeLa cells were transfected with pCMV-HA-eIF2β and cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-HA antibody. Immunoprecipitates were left untreated or dephosphorylated with PP2A catalytic subunit and re-phosphorylated with CK2 holoenzyme. Samples were subjected to SDS/PAGE followed by autoradiography (AR) and Western blotting against HA antibody to ensure equal amount of HA–eIF2β in the assay.

The 32P incorporation into eIF2β purified from rabbit reticulocyte lysates catalysed in vitro by CK2 has been shown to be enhanced by prior dephosphorylation of eIF2β by either alkaline phosphatase or PP2A [21]. In order to explore if this also occurs in HeLa cells, HA–eIF2β from transfected HeLa cells was immunoprecipitated with the anti-HA antibody and the immunoprecipitate was subjected to phosphorylation by human recombinant CK2 holoenzyme. A parallel experiment was performed in which the immunoprecipitated HA–eIF2β was subjected to dephosphorylation with the PP2Ac followed by rephosphorylation with CK2 holoenzyme. The results showed that the untreated HA–eIF2β present in the immunoprecipitates was still phosphorylated by CK2, which suggests that the CK2-targeted sites are not completely phosphorylated in vivo (Figure 1B). Nonetheless, the increase in the extent of phosphorylation achieved in the samples of HA–eIF2β that had been subjected to prior dephosphorylation by PP2A indicated that at least some of these CK2 sites are phosphorylated in vivo.

CK2 inhibitors block HA–eIF2β phosphorylation in HeLa cells

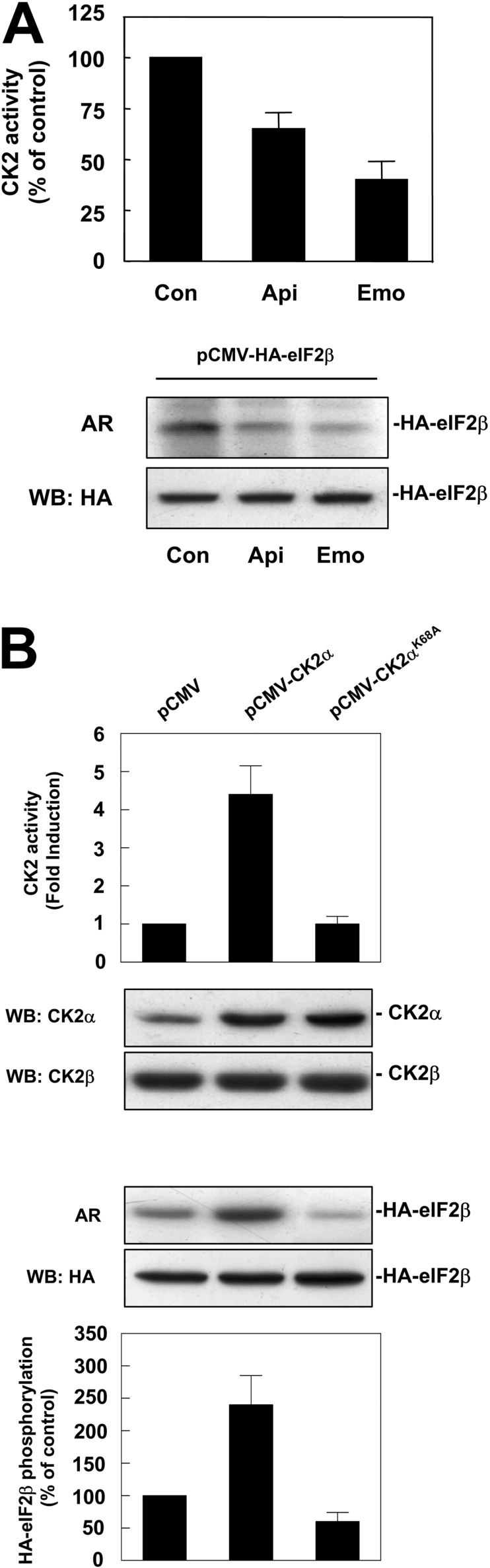

The results shown above support a role of CK2 in the basal phosphorylation of eIF2β, but experimental evidence of its real involvement in this process in living cells was lacking. As a first approach to this question, we used chemical inhibitors of CK2. Apigenin and emodin are two structurally different compounds that have been shown to inhibit CK2 activity in cultured cells [16,39]. As expected from previous reports [16], treatment of HeLa cells with these compounds led to a decrease in the CK2 activity in the cell extracts (Figure 2A). At 40 μM, emodin decreased CK2 by 60%, whereas the inhibition caused by apigenin was approx. 40%. Addition of these inhibitors to HeLa cells at the onset of their labelling with [32P]-phosphate caused a marked decrease in HA–eIF2β phosphorylation in vivo (Figure 2A, lower panels), without affecting the total HA–eIF2β levels. This effect is dose-dependent as shown in Supplementary Figure 1 (http://www.BiochemJ.org/bj/394/bj3940227add.htm).

Figure 2. HA–eIF2β is phosphorylated by CK2 in HeLa cells.

(A) pCMV-HA-eIF2β transfected HeLa cells were labelled with [32P]Pi in the absence or presence of CK2 inhibitors apigenin and emodin (40 μM) during the labelling time as indicated. An aliquot of cell lysate was tested for CK2 activity over CK2-specific peptide substrate RRRAADSDDDDD to monitor CK2 inhibition on the assay (upper panel). Samples were immunoprecipitated with anti-HA antibody and subjected to SDS/PAGE followed by autoradiography (AR) and Western blotting against HA antibody to ensure equal amount of HA–eIF2β in the assay (lower panels). (B) HeLa cells were transfected with pCMV, pCMV-CK2α or pCMV-CK2αK68A and cell lysates were assayed for CK2 activity over CK2-specific peptide substrate RRRAADSDDDDD and subjected to Western blotting against CK2α and CK2β antibodies (upper panels). In a parallel experiment, HA–eIF2β was co-transfected with the CK2α plasmids indicated above and HeLa cells were labelled with [32P]Pi. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-HA antibody and subjected to SDS/PAGE followed by autoradiography (AR) and Western blotting against HA antibody to ensure equal amount of HA–eIF2β in the assay. Quantification of autoradiography is also shown in the graph (lower panels).

Overexpression of the wild-type or the dead mutant forms of CK2α affects the phosphorylation of eIF2β in HeLa cells

The identity of CK2 as an eIF2β kinase in vivo was also studied by co-transfecting HeLa cells with the vector encoding HA–eIF2β and pCMV plasmids encoding either the active catalytic subunit of CK2 (CK2α) or its dominant inactive mutant (CK2αK68A). Cell extracts transfected with either plasmid showed a 4–5-fold increase in CK2α content (Figure 2B), but they did not alter the CK2β levels. A concomitant increase in CK2 activity in the model peptide substrate was observed in extracts from cells overexpressing pCMV-CK2α wild-type, whereas the extracts from cells transfected with pCMV-CK2αK68A did not show any significant change with respect to the control. This is in agreement with the data reported by others [38], in cells where overexpression of the kinase-dead mutants did not alter the activity in the extracts although it decreased the autophosphorylation of CK2β in vivo. Interestingly, the overexpression of CK2αK68A decreased the phosphorylation in vivo of HA–eIF2β to about one-half, whereas overexpression of CK2α wild-type increased it by 2–3-fold. These results strongly support the idea that CK2 is involved in the in vivo phosphorylation of eIF2β.

CK2 phosphorylates human eIF2β on Ser2 and Ser67

In a previous study on human recombinant eIF2β, we had observed that the CK2 holoenzyme-targeted sites in vitro were located within the N-terminal 138-residues segment of hr-eIF2β (where hr is human recombinant). As 1.25 mol of phosphate was incorporated per mol of eIF2β, we concluded that hr-eIF2β must contain at least two CK2 sites [16]. Ser2 and Ser67 have been shown to serve as phosphorylation sites for CK2 in rabbit reticulocyte eIF2β [21]. The sequence corresponding to the phosphorylation site at Ser2 is conserved from human to chicken eIF2β (Figure 3A). The Ser67 site is also conserved in other mammals but is replaced by a threonine in the chicken sequence. None of these potential phosphorylation sites are present in Drosophila and yeast eIF2β sequences. Interestingly, Ser13, the site of phosphorylation by PKC, is also conserved in vertebrates but not in the other species, whereas Ser218, the phosphorylation site for PKA [21], is conserved even in Drosophila, although it is absent from yeast.

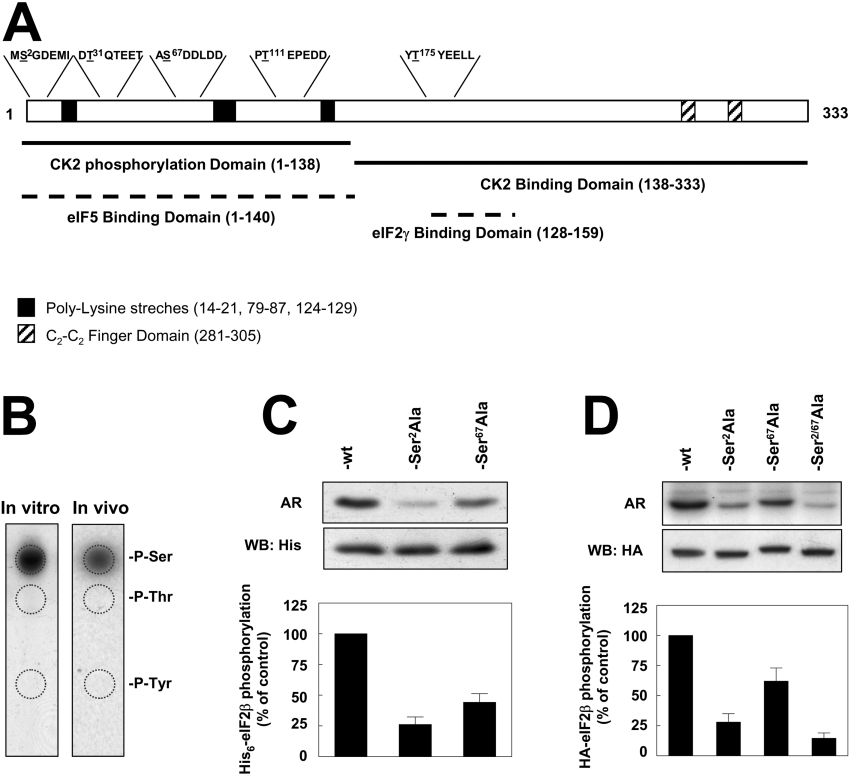

Figure 3. eIF2β is phosphorylated in vitro and in vivo on Ser2 and Ser67.

(A) Domain structure of eIF2β. Potential CK2 phosphorylation sequences are indicated over the sequence of the open box representing the polypeptide chain, and phosphorylation sites are underlined. Black boxes indicate polylysine stretches and shadowed boxes the C2-C2 finger domain. Black lines indicate the characterized domains for interaction and phosphorylation by CK2. Discontinuous lines indicate the location in human eIF2β for binding to eIF5 and eIF2γ extrapolated from the data reported on yeast. (B) Phospho amino acid analysis of (left panel) His6–eIF2β phosphorylated by CK2 holoenzyme resolved by SDS/PAGE and transferred on to PVDF membrane and (right panel) HA–eIF2β from HeLa cells labelled with [32P]Pi, immunoprecipitated with anti-HA, resolved by SDS/PAGE and transferred on to PVDF membrane. In both cases, radioactive bands were excised from the membrane and the samples were analysed by one-dimensional high-voltage electrophoresis on a TLC cellulose plate and autoradiography. P-Ser, P-Thr and P-Tyr denote the positions of phosphoserine, phosphothreonine and phosphotyrosine respectively as determined by ninhydrin staining of standards. (C) Densitometry of the autoradiography of in vitro phosphorylation of His6–eIF2β, His6–eIF2βS2A and His6–eIF2βS67A by CK2 holoenzyme. Western blotting with anti-His6 was carried out to ensure equal amount of protein in the assay. (D) In vivo phosphorylation of HA–eIF2β, HA–eIF2βS2A, HA–eIF2βS67A and HA–eIF2βS2/67A. Transfected HeLa cells were labelled with [32P]Pi and cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-HA antibody and subjected to SDS/PAGE followed by autoradiography and Western blotting against HA antibody to ensure equal amount of HA–eIF2β in the assay. Densitometries of the autoradiography are shown.

As to the potential existence of other CK2 phosphorylation sites in the human eIF2β, inspecting its sequence also evidenced the presence of Thr31, Thr111 and Thr175 which have an acidic residue at position +3 with no basic residues in between, which is typical of the consensus sequence for CK2 phosphorylation [15]. Thr111 appears to be unique to the human eIF2β sequence, whereas Thr31 is present in both human and chicken, but it is absent from the rabbit, rat and mouse sequences and Thr175 is conserved in all of these species except for yeast.

As a first approach to discerning which of these sites are phosphorylated in vivo, phospho amino acid analysis was performed. Only serine sites were phosphorylated in HA–eIF2β immunoprecipitated from HeLa cells incubated with [32P]Pi (Figure 3B). A similar result was obtained with hr-eIF2β phosphorylated in vitro with human recombinant CK2. These results delimitated the search for potential CK2 phosphorylation sites to Ser2 and Ser67 in the N-terminal region of eIF2β.

The efficiency of Ser2 and Ser67 serving as phosphorylation sites in human eIF2β was studied first in vitro by using recombinant His6-tagged forms of eIF2β expressed in bacteria. As shown in Figure 3(C), Ser-to-Ala mutation at each one of these serine residues decreased the ability of His6–eIF2β to serve as substrate for CK2. However, the effect was more dramatic when Ser2 was mutated than with mutation at Ser67.

To discern if Ser2 and Ser67 are authentic phosphorylation sites and to determine if they are equally phosphorylated in vivo, a series of plasmids encoding HA–eIF2β mutants was constructed. HeLa cells transfected with these plasmids were metabolically 32P-labelled and the extracts were subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-HA antibodies. The results showed that phosphorylation of the S2/67A double mutant was less than 20% that of wild-type HA–eIF2β (Figure 3D). This confirmed Ser2 and Ser67 as the prevalent phosphorylation sites in vivo, although some other minor sites must exist in HA–eIF2β. Phosphorylation of the single S67A mutant was lower than that of wild-type HA–eIF2β, whereas the S2A mutant was markedly reduced. Taken together, the results pointed to Ser2 as a preferred phosphorylation site for CK2, whereas phosphorylation at Ser67 would be less prevalent.

It is worth noting that mutation at Ser67 did not alter the electrophoretic mobility of HA–eIF2β in SDS/PAGE, whereas mutation at Ser2, either alone or in combination with mutation at Ser67, caused a slight but consistent increase in its mobility. This would point to phosphorylation at Ser2 as one of the factors that contributes to the anomalous behaviour of eIF2β in gel electrophoresis.

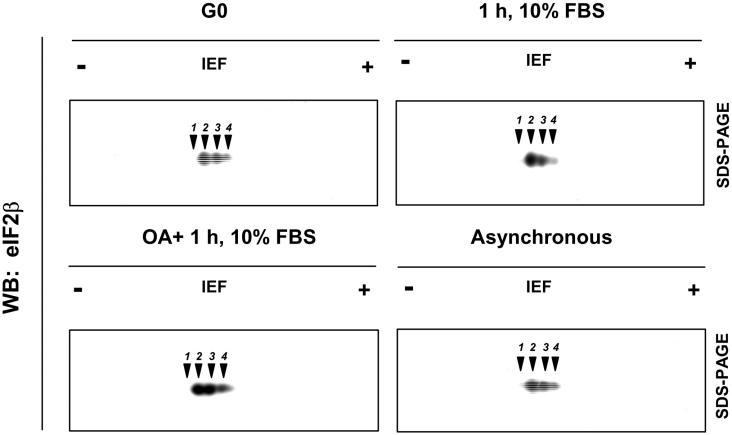

Phosphorylation of eIF2β in HeLa cells is affected by serum and okadaic acid

Previous reports have shown that in HeLa cells, endogenous eIF2β gives rise to different spots when analysed by two-dimensional gel electrophoresis [40]. The presence of several spots is indicative of the coexistence of in vivo forms of eIF2β with different phosphorylation levels. On the other hand, serum stimulation has been reported to provoke the conversion of these forms into a single form, but whether this involves conversion into a defined, specifically phosphorylated form of eIF2β or its complete dephosphorylation has not been established yet. As a first step towards approaching this question, we decided to monitor the changes in the phosphorylated forms of the endogenous eIF2β in HeLa cells subjected to serum deprivation, re-addition of 10% (v/v) serum or asynchronously growing. Moreover, since PP2A is potentially involved in eIF2β dephosphorylation [21], we decided to study the effect of okadaic acid, a well-known inhibitor of PP1 and PP2A, on the eIF2β response to serum stimulation. In serum-deprived HeLa cell extracts, eIF2β is present mainly in three forms that differ in their pI; the less prominent one corresponds to that with a more acidic pI (Figure 4). Addition of 10% serum shifted the pattern towards the more basic pI range and led to the more acidic spot decreasing and to a marked decrease in the intermediate form. The effects of serum stimulation were not observed in HeLa cells pretreated with okadaic acid. These results confirmed that phosphorylation of eIF2β is a dynamic process and supports the potential involvement of PP1/PP2A-type phosphatases in this process.

Figure 4. Phosphorylation of eIF2β in HeLa cells is affected by serum and okadaic acid.

HeLa cells were serum-starved for 24 h with 0.5% serum and left untreated (G0), re-stimulated for 1 h with 10% serum (1 h, 10% FBS), re-stimulated for 1 h with 10% serum in the presence of okadaic acid (1 μM) (OA+1 h, 10% FBS) or left in 10% FBS as the normal growth conditions (Asynchronous). Equal amounts of cell extract protein were precipitated in 10% trichloroacetic acid, subjected to two-dimensional electrophoresis as described in the Experimental section and developed with anti-eIF2β antibodies. Spot localization is indicated by numbers over arrowheads. The experiment was performed three times with similar results. WB, Western blot; IEF, isoelectric focusing.

Ser2 is constitutively phosphorylated in human eIF2β

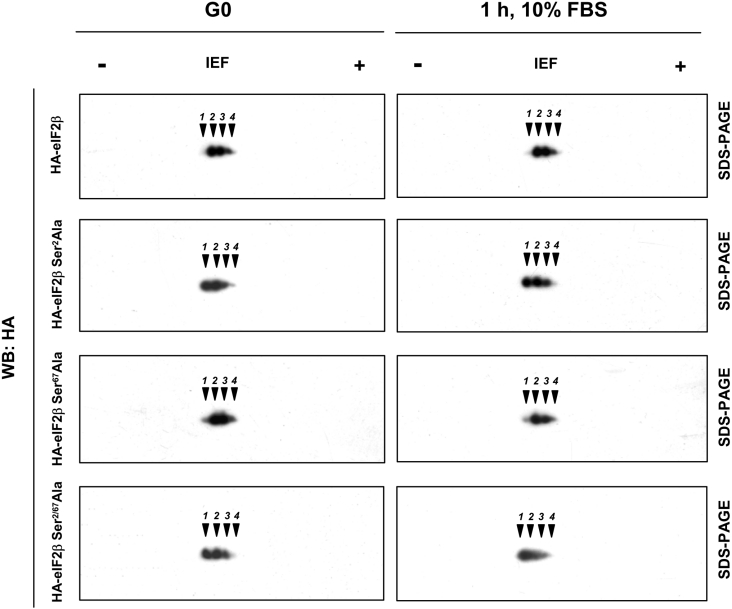

In order to gain a deeper insight into the contribution of the CK2 sites to the phosphorylation status of eIF2β in HeLa cells, the immunoprecipitates obtained from serum-starved HeLa cells transfected with either wild-type or mutant forms of HA–eIF2β were subjected to two-dimensional gel electrophoresis analysis. A set of three spots was specifically detected with the anti-HA antibodies in the samples of HeLa cells overexpressing wild-type HA–eIF2β (Figure 5). The most prominent ones were spots denoted as 2 and 3. This pattern was similar to that detected with the endogenous eIF2β under similar conditions, which evidenced that the overexpressed HA–eIF2β form behaved like the endogenous one and validated the approach used. Mutation at Ser67 did not significantly affect the pattern of spots but, in contrast with this, mutation at Ser2 provoked the appearance of a new spot with a more basic pI value, and in fact it shifted the whole pattern of the spots to higher pIs. The S2/67A double mutant behaved like the S2A mutant. Taken together, the results indicate that almost all eIF2β subunits are constitutively phosphorylated at Ser2 in vivo, whereas phosphorylation at Ser67 and other additional sites is restricted to a limited number of eIF2β subunits.

Figure 5. Ser2 is constitutively phosphorylated in human eIF2β.

HA–eIF2β, HA–eIF2βS2A, HA–eIF2βS67A and HA–eIF2βS2/67A transfected HeLa cells were serum-starved for 24 h with 0.5% serum and left untreated (G0) or re-stimulated for 1 h with 10% serum (1 h, 10% FBS). Equal amounts of cell extracts were precipitated in 10% trichloroacetic acid, subjected to two-dimensional electrophoresis as described in the Experimental section and developed with anti-HA antibodies. Spot localization is indicated by numbers over arrowheads. The experiment was performed three times with similar results. WB, Western blot; IEF, isoelectric focusing.

Next, we asked if re-adding 10% serum to starved HeLa cells would alter the phosphorylation pattern of HA–eIF2β. No major changes in this pattern were observed with wild-type HA–eIF2β (Figure 5). These results are consistent with the idea that the phosphorylation state of Ser2 and Ser67 does not decrease in response to serum stimulation, whereas some of the additional phosphorylation sites would become dephosphorylated. This agrees with the activity pattern of CK2, which is constitutively active and increased in nuclear fraction after serum re-stimulation but presented minor changes in cytoplasmic and membrane fractions where almost all the cellular eIF2β protein is located (see Supplementary Figure 2 at http://www.BiochemJ.org/bj/394/bj3940227add.htm).

Since previous reports have shown that mutation at CK2 phosphorylation sites affected the half-life of IκBα (inhibitory κBα) [41] and CK2β [42], we decided to test if mutation at Ser2 and Ser67 affected the stability of eIF2β. Pulse–chase experiments in transfected HeLa cells showed that the Ser2 and Ser67 double mutant form of HA–eIF2β decayed with a half-life similar to that of the wild-type (see Supplementary Figure 3 at http://www.BiochemJ.org/bj/394/bj3940227add.htm). This argues against phosphorylation having a role at CK2 sites in the stability of HA–eIF2β in these cells.

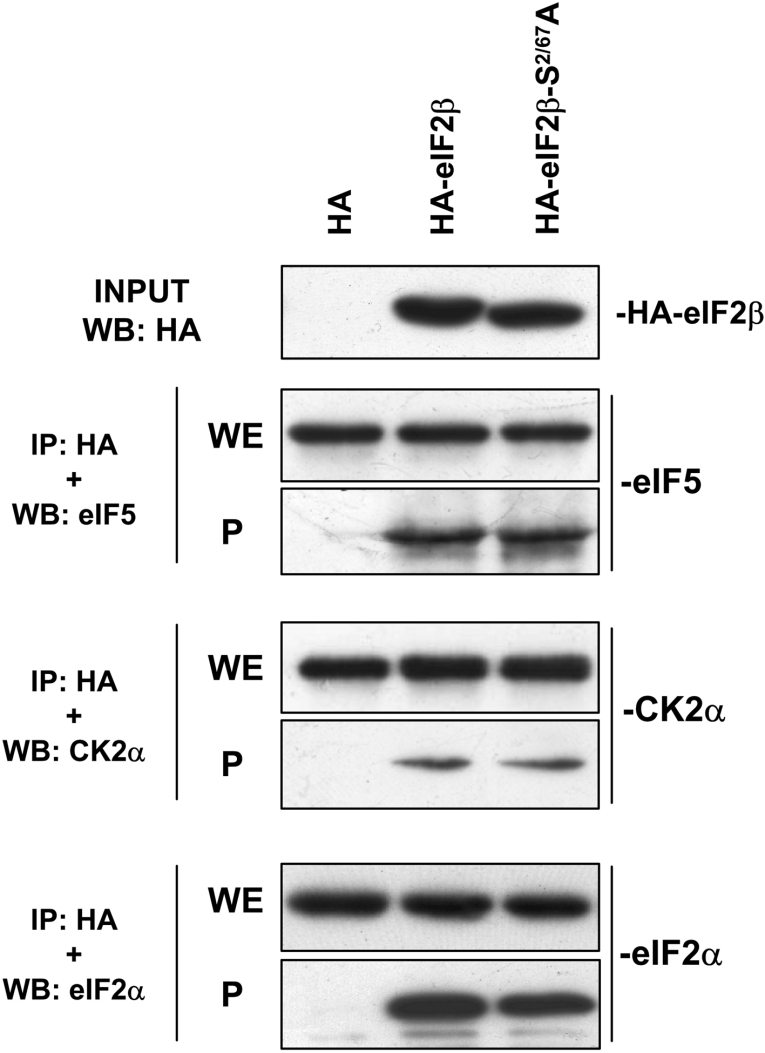

The eIF2β S2/67A mutant was incorporated into the eIF2 trimer and associates with CK2 and eIF5 in vivo

The ability of the mutant protein to form the eIF2 trimer and to become integrated into typical complexes of eIF2β, such as those with eIF5 [9] or with CK2α [16], was also studied. The incorporation of the HA–eIF2β forms into eIF2 trimer was monitored by the presence of eIF2α and eIF2γ in the immunoprecipitates obtained from transfected cells (Supplementary Figure 4 at http://www.BiochemJ.org/bj/394/bj3940227add.htm). As observed in Figure 6, the S2/67A double mutant form of HA–eIF2β was incorporated into the eIF2 trimer as efficiently as the HA–eIF2β wild-type. The association between HA–eIF2β and either eIF5 or CK2α was also studied. The presence of either eIF5 or CK2α in the pellets immunoprecipitated with anti-HA antibodies, obtained from HeLa cells overexpressing the double mutant, was similar to that detected in cells overexpressing HA–eIF2β wild-type. This indicates that the double phosphorylation site mutant retained the ability to bind to these proteins as efficiently as the wild-type form of eIF2β.

Figure 6. HA–eIF2β and CK2 phosphorylation mutant HA–eIF2βS2/67A associates with eIF5, CK2α and eIF2α.

HeLa cells were transfected with pCMV-HA, pCMV-HA-eIF2β and pCMV-HA-eIF2βS2/67A and cell lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-HA antibody. Immunoprecipitates (P) and an aliquot of the whole cell extract (WE) were subjected to SDS/PAGE, transferred on to PVDF membranes and developed with antibodies against eIF5, CK2α and eIF2α as indicated. The top panel indicates the input used for the assay. IP, immunoprecipitation.

Ser2 and Ser67 are necessary for sustaining protein synthesis at a high rate

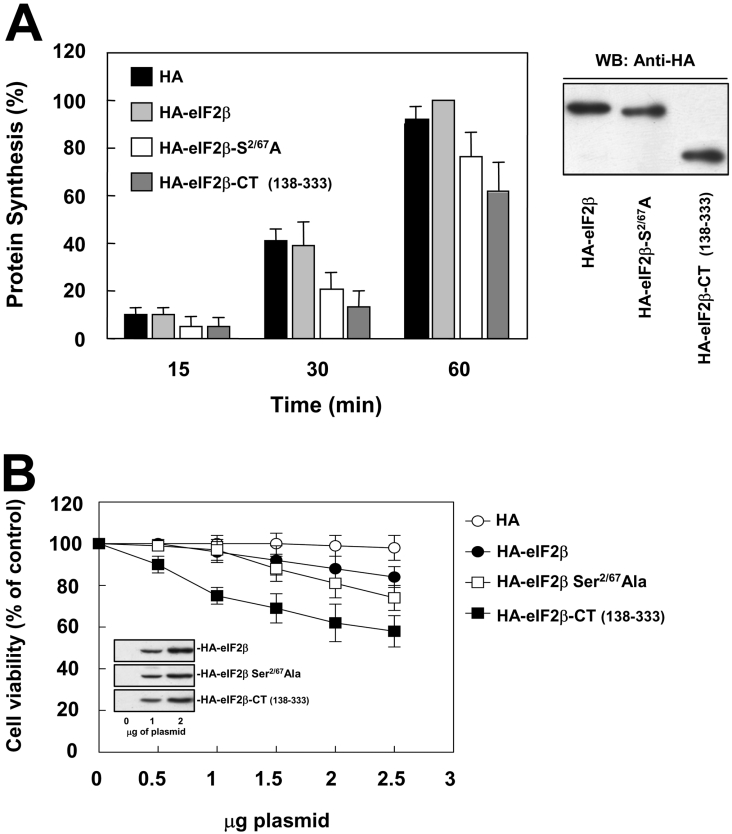

Since eIF2 may participate in different stages of translation initiation, we decided to use an assay for global protein synthesis in transfected HeLa cells in order to evaluate the effects of the overexpression of the wild-type and mutant forms of eIF2β. Moreover, we decided to extend this study by exploring the effects of the overexpression of an N-terminal truncated form of eIF2β lacking residues 1–137, herein designated as HA–eIF2β-CT. In a previous work, we observed that this truncated form was able to bind to CK2 but it was not a substrate for this protein kinase [16]. To standardize the assay conditions, the HeLa cells were serum-starved for 24 h and then stimulated with 10% FBS after adding the [35S]methionine/cysteine mixture. As shown in Figure 7(A), the overexpression of wild-type HA–eIF2β did not essentially affect the initial rate of protein synthesis, whereas the expression of HA–eIF2β-CT caused a decrease in the rate of protein synthesis to approx. 50%. The expression of the double mutant form of HA–eIF2β slowed down the rate of protein synthesis to values intermediate of those observed with wild-type and HA–eIF2β-CT.

Figure 7. Mutation of CK2 phosphorylation sites on HA–eIF2β impairs protein synthesis at a high rate but has minor effects on cell viability.

(A) HeLa cells were transfected with pCMV-HA, pCMV-HA-eIF2β, pCMV-HA-eIF2βS2/67A and pCMV-HA-eIF2β(138-333) and serum-starved for 24 h. Then cells were re-stimulated with 10% FBS in the presence of [35S]methionine/cysteine for the indicated times. Cell extracts were analysed for radioactivity incorporation as indicated in the Experimental section. Radioactivity was expressed taking the maximum value as 100%. An aliquot of samples were subjected to Western blotting with anti-HA antibody to ensure equal expression levels of transfected proteins on the assay. (B) HeLa cells were transfected with increasing amounts of pCMV-HA, pCMV-HA-eIF2β, pCMV-HA-eIF2βS2/67A or pCMV-HA-eIF2β (138–333), and after 48 h of transfection, cell viability was analysed using the MTT [3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide] assay. Cell viability was expressed taking the maximum value as 100%.

Overexpression of the N-terminal truncated form of eIF2β is highly deleterious to HeLa cell viability

Inhibition of protein synthesis by different agents induces cell death. As the overexpression of the double phosphorylation sites mutant and the N-terminal truncated forms of eIF2β decreased protein synthesis to different levels, we decided to test if these changes affected cell viability. To this end, HeLa cells were transfected with increasing amounts of the vectors encoding the HA–eIF2β wild-type, the double phosphorylation sites mutant or for HA–eIF2β-CT. After 48 h of culture in complete media, the number of living cells was counted. A parallel experiment was performed in which total cell extracts were obtained and used to monitor the expression levels of the different eIF2β forms. As shown in Figure 7(B), the overexpression of HA–eIF2β caused a small effect on cell viability, with a 15% decrease in the cell number at the highest dose of transfection tested. This effect could be due to competition effects between the endogenous eIF2β and the HA–eIF2β overexpressed to high levels for binding to other cellular factors that could affect the interaction of functional eIF2 contained in the 43 S pre-initiation complex as suggested by others [43]. The increase in cell death was slightly more evident in cells transfected with the HA–eIF2β S2/67A mutant, and became particularly marked in those overexpressing the HA–eIF2β-CT form. In fact, the toxic effects of the HA–eIF2β-CT form were clearly detectable at doses where HA–eIF2β S2/67A was ineffective. It is worth noting that in our experiments, a range of 25–30% of the immunoprecipitated HA–eIF2β, HA–eIF2β S2/67A and HA–eIF2β-CT contains endogenous eIF2α and eIF2γ, which indicates that part of the overexpressed protein is incorporated into the eIF2 holoprotein (Supplementary Figure 4 at http://www.BiochemJ.org/bj/394/bj3940227add.htm). Taken together, these results suggest that the effects observed in protein synthesis and cell viability could not be attributed to a decreased fraction of eIF2 holoprotein or to a cytotoxic effect of HA–eIF2β overexpression by itself.

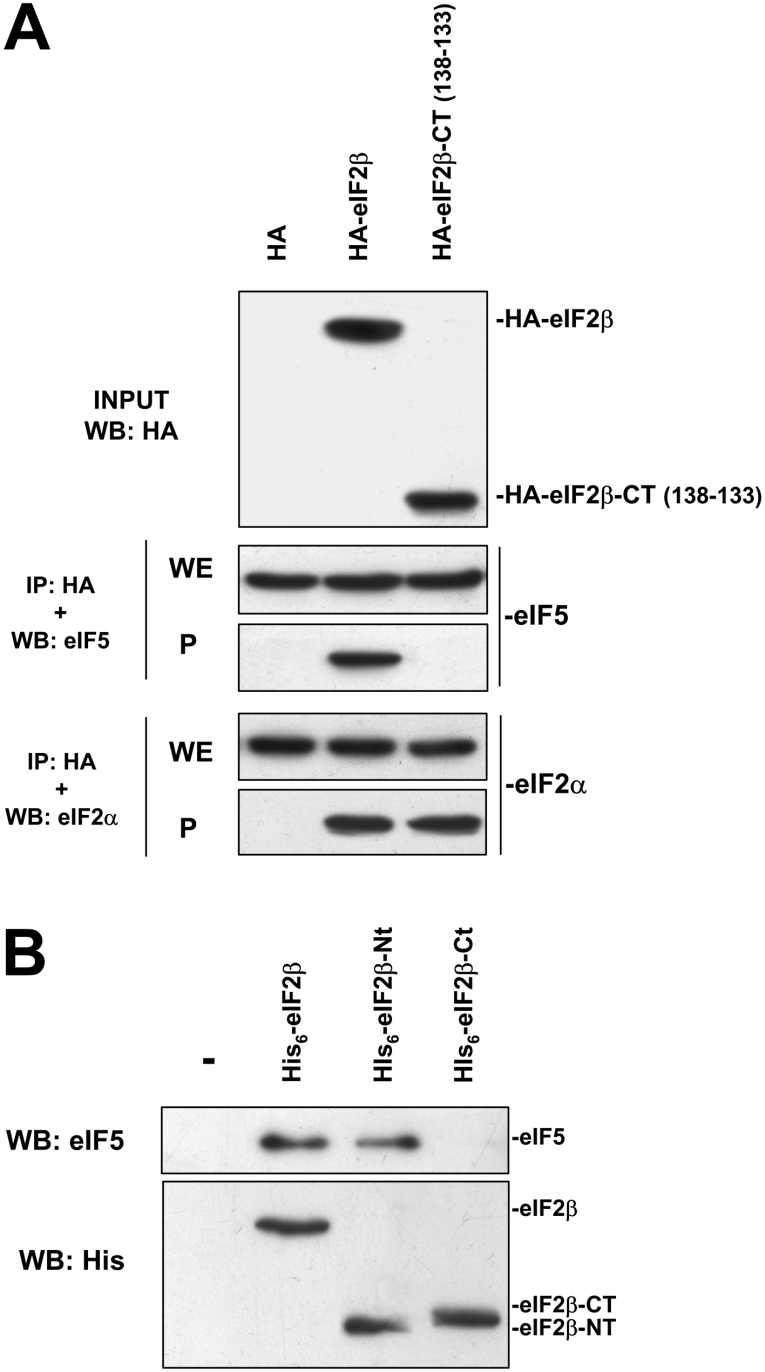

The N-terminal truncated form of eIF2β binds to eIF2α but not to eIF5

The marked differences between HA–eIF2β-CT and HA–eIF2β wild-type or S2/67A double mutant in protein synthesis and cell viability prompted us to study if they could be due to a defect in the ability of HA–eIF2β-CT to associate with other cellular components. In a previous study, we demonstrated that eIF2β-CT was able to bind to CK2α as efficiently as eIF2β [16].

The immunoprecipitation technique was also used to study the incorporation of HA–eIF2β-CT into the eIF2 trimer and its potential interaction with eIF5. The results shown in Figure 8(A) evidenced that HA–eIF2β-CT was able to bind to endogenous eIF2α as efficiently as HA–eIF2β wild-type. In contrast, a marked difference was observed concerning the binding to eIF5, since this factor was not detected in the immunoprecipitates from cells overexpressing HA–eIF2β-CT, although eIF5 was clearly detected in the immunoprecipitates from cells overexpressing HA–eIF2β wild-type or the S2/67A mutant. To ensure that the N-terminal domain of eIF2β was responsible for eIF5 binding, pull-down experiments using different recombinant eIF2β forms were carried out. As shown in Figure 8(B), His6–eIF2β and His6–eIF2β-NT (1–137), but not His6–eIF2β-CT (138–333), bind to eIF5 from HeLa cell extracts.

Figure 8. N-terminal deletion mutant HA–eIF2β (HA–eIF2β 138–333) does no associate with eIF5.

(A) HeLa cells were transfected with pCMV-HA, pCMV-HA-eIF2β and pCMV-HA-eIF2β (138–333) and cell lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-HA antibody. Immunoprecipitates (P) and an aliquot of the whole cell extract (WE) were subjected to SDS/PAGE, transferred on to PVDF membranes and developed with antibodies against eIF5 and eIF2α as indicated. The top panel indicates the input used for the assay. (B) His6–eIF2β, His6–eIF2βCT (138–333) or His6–eIF2βNT (1–137) was incubated with 500 μg of HeLa cell extract. A slurry of Ni-NTA–agarose (1:1; 20 μl) was added to recover recombinant proteins and eIF5 bound to His6-tagged proteins was analysed by SDS/PAGE and Western blotting with anti-eIF5 antibody (upper panel). An aliquot of the experiment was analysed by SDS/PAGE and Western blotting using anti-His6 antibody to ensure equal amount of recombinant protein in the assay (lower panel).

Taken together, these results support the notion that the N-terminal region of human eIF2β does not participate in its integration into the eIF2 trimer as reported previously for yeast eIF2 [9]. Moreover, they also show that the N-terminal region is absolutely required for its binding to eIF5 in vivo, as observed previously by others in in vitro assays [10]. In addition, the inability to bind eIF5 might provide an explanation for the marked effects of the overexpression of HA–eIF2β-CT on protein synthesis.

DISCUSSION

Phosphorylation of eIF2 by CK2 in vitro is unusual because in yeast and in invertebrates it takes place specifically in its eIF2α subunit, although in residues different from the equivalent of Ser51 [29], whereas in mammals it occurs exclusively in its eIF2β subunit [3,21]. Although different lines of in vitro evidence pointed to CK2 being potentially involved in eIF2β phosphorylation in living cells, no studies on the real involvement of CK2 in this process using in vivo approaches have been undertaken to date. Our present results combining in vitro studies with purified CK2 and experiments in vivo designed to alter CK2 activity demonstrate that CK2 is really involved in the in vivo phosphorylation of eIF2β. Previous reports based on the overexpression of mutated forms of mammalian eIF2Bϵ (the catalytic subunit of eIF2B) [35] and eIF5 [44] have shown that these translation initiation factors are also phosphorylated in vivo at CK2 sites. Moreover, experiments in yeast using strains that express either the wild-type form or the temperature-sensitive catalytic subunit of CK2 showed the involvement of CK2 in the in vivo phosphorylation of eIF5 [45]. However, to our knowledge, the present paper is the first report showing that changes of CK2 activity in vivo alter the phosphorylation of a translation initiation factor in mammalian cells.

Our results show that Ser2 and Ser67 are the main CK2 phosphorylation sites in human eIF2β. These sites are located at the N-terminal extension of eIF2β characteristic of eukaryotes but absent from Archaea, a region that also harbours the lysine stretches, or lysine boxes, present in yeast and mammals. The absence of the CK2 phosphorylation sites in this N-terminal region of yeast and invertebrate eIF2β indicates that the CK2 phosphorylation sites were incorporated during evolution and are probably required in mammals. However, the functional meaning of the CK2-catalysed eIF2β phosphorylation has never been firmly established. Our results show that mutation of Ser2 and Ser67 to alanine residues impairs the properties of this subunit. It must be emphasized that these effects are not due merely to an exacerbated increase in the eIF2β protein since the defect was not observed in cells overexpressing the wild-type form of eIF2β to similar levels. The decrease in the rate of protein synthesis was not due to a loss of incorporation into the eIF2 trimer, as indicated by the presence of eIF2α and eIF2γ in the complexes with either wild-type or S2/67A mutant forms of eIF2β, or to a defect in binding to eIF5. It is then conceivable that the lack of phosphorylation at the positions corresponding to Ser2 and Ser67 might alter the conformation of the N-terminal region of eIF2β required for its proper participation in translation initiation at a step beyond the interaction with eIF5.

The importance of the phosphorylation at Ser2 can be specially inferred from the data supplied by the two-dimensional maps, which indicate that almost all of the cellular eIF2β subunit is constitutively phosphorylated at this site. Constitutive phosphorylation at Ser67 has been reported previously for the rabbit eIF2β subunit [21]. Our results agree with the idea that a significant fraction of the total HA–eIF2β is also phosphorylated at Ser67, and this phosphorylation can also be considered as constitutive as it did not change upon serum stimulation.

Another interesting observation in our present study is that besides being phosphorylated at Ser2 and Ser67, human eIF2β is also phosphorylated at other sites, and the phosphorylation at least in some of these sites decreases in response to serum. Moreover, the presence of several spots in the samples from the double phosphorylation site mutant suggests that phosphorylation at the two CK2 sites does not seem to be hierarchical to the phosphorylation at the other sites.

The N-terminal region of eIF2β is unique to eukaryotes, but its central/C-terminal regions show a high homology to the archaeal aIF2β, the latter resembling an N-truncated form of eIF2β. The N-terminal region of yeast eIF2β is dispensable for binding of this subunit to eIF2γ. The residues involved in this binding are located at the central domain of eIF2β. This interaction is crucial for assembling the eIF2 trimer because no direct eIF2β–eIF2α binding seems to occur [19]. Our results agree with the idea that the N-terminal region is not involved in assembling the eIF2 as HA–eIF2β-CT was incorporated into complexes with eIF2α as efficiently as the HA-tagged wild-type form of eIF2β.

Previous studies in yeast have shown that the N-terminal domain of eIF2β is crucial for its interaction with the catalytic subunit of eIF2B (eIF2Bϵ) and with eIF5 [9]. Interaction with the latter seems especially important for the formation of the multifactor complex as it enhances the binding of eIF5 to the NIP1/eIF3c [12]. In vitro studies using recombinant proteins corresponding to human eIF2β deletion mutants showed that the interaction with eIF5 requires the lysine boxes in the N-terminal domain of eIF2β [9,10], but the possibility that other sequences neighbouring the second lysine box are also involved in eIF5 binding has been suggested for yeast [7]. Our results show that mutation at Ser2 and Ser67, which are located in the acidic sequences preceding the first and the second lysine boxes, does not seem to affect eIF2β–eIF5 binding. On the other hand, our results support the notion that the binding sites for eIF5 are located exclusively in the N-terminal region of eIF2β.

The effects of the overexpression of HA–eIF2β-CT on protein synthesis inhibition and HeLa cell death were more marked than those caused by the overexpression of similar levels of the double phosphorylation site mutant. In this context, it is worth noting that previous studies in yeast have observed that deleting the regions corresponding to the three lysine blocks in eIF2β compromise yeast growth [7], but no data concerning mammalian cells are available to date. Our results indicate that the loss of eIF5 binding observed with HA–eIF2β-CT can be at least one of the factors that underlie the marked effects on protein synthesis and decrease in mammalian cell survival.

In previous studies, we had observed that eIF2 forms complexes with CK2 and their interaction involves direct contacts between the central/C-terminal regions of eIF2β (eIF2β-CT) and the catalytic subunit of CK2 (CK2α) [16]. The coimmunoprecipitation of CK2α with HA–eIF2β agrees with the existence of these interactions. Moreover, the lack of effect caused by mutation at the CK2 phosphorylation sites at the N-terminal region of eIF2β was in agreement with the idea that this region does not contribute to this binding [16]. This would leave the N-terminal region of eIF2β accessible to bind to other initiation factors when assembling the different complexes formed during the translation initiation process. Thus the simultaneous binding of eIF2β to CK2α and other eIFs cannot be disregarded. At this point, it is worthwhile recalling that eIF5 [44], the catalytic subunit of eIF2B (eIF2Bϵ) [35], and some of the subunits of eIF3 [46] are substrates for CK2. Therefore such a binding might help to locate CK2 in the close vicinity of certain specific substrates. It is tempting, as a result, to speculate that the overexpression of HA–eIF2β-CT could interfere with the formation of some of these complexes, such as the eIF5–eIF2β–CK2α complex, and might contribute to the cytotoxic effects that this causes in HeLa cells.

Online data

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr S. Bartolomé (LAFEAL-UAB-Barcelona) for gel scanning and Figure presentation, and to Dr S. Mackenzie (Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona) for criticisms and corrections of the language. This work was supported by grants SAF2002-03239 from MCYT (Ministero de Ciencia y Tecnología) and 2001SGR00199 from DGR (Direccío General de Recerca) (GENCAT), Spain.

References

- 1.Preiss T., Hentze M. W. Starting the protein synthesis: eukaryotic translation initiation. BioEssays. 2003;25:1201–1211. doi: 10.1002/bies.10362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kapp L. D., Lorsh J. R. The molecular mechanisms of eukaryotic translation. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2004;73:657–704. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.73.030403.080419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kimball S. R. Eukaryotic initiation factor eIF2. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 1999;31:25–29. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(98)00128-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krishnamoorthy T., Pavitt G. D., Zhang F., Dever T. E., Hinnebusch A. G. Tight binding of the phosphorylated α subunit of initiation factor 2 (eIF2α) to the regulatory subunits of guanine nucleotide exchange factor eIF2B is required for inhibition of translation initiation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2001;21:5018–5030. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.15.5018-5030.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thompson G. M., Pacheco E., Melo E. O., Castilho B. A. Conserved sequences in the β subunit of archaeal and eukaryal translation initiation factor 2 (eIF2), absent from eIF5, mediate interaction with eIF2γ. Biochem. J. 2000;347:703–709. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nika J., Rippel S., Hannig E. M. Biochemical analysis of the eIF2βγ complex reveals a structural function for eIF2α in catalyzed nucleotide exchange. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:1051–1056. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007398200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Laurino J. P., Thompson G. M., Pacheco E., Castilho B. A. The β subunit of eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2 binds mRNA through the lysine repeats and a region comprising the C2-C2 motif. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1999;19:173–181. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.1.173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kimball S. R., Heinzinger N. K., Horetsky R. L., Jefferson L. S. Identification of interprotein interactions between the subunits of eukaryotic initiation factors eIF2 and eIF2B. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:3039–3044. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.5.3039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Asano K., Krishnamoorthy T., Phan L., Pavitt G. D., Hinnebusch A. G. Conserved bipartite motifs in yeast eIF5 and eIF2Bϵ, GTPase-activating and GDP-GTP exchange factors in translation initiation, mediate binding to their common substrate eIF2. EMBO J. 1999;18:1673–1688. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.6.1673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Das S., Maiti T., Das K., Maitra U. Specific interaction of eukaryotic translation initiation factor 5 (eIF5) with the β-subunit of eIF2. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:31712–31718. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.50.31712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Valasek L., Nielsen K. H., Hinnebusch A. G. Direct eIF2–eIF3 contact in the multifactor complex is important for translation initiation in vivo. EMBO J. 2002;21:5886–5898. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Singh C. R., Yamamoto Y., Asano K. Physical association of eukaryotic initiation factor (eIF)5 carboxyl-terminal domain with the lysine-rich eIF2β segment strongly enhances its binding to eIF3. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:49644–49655. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409609200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kebache S., Zuo D., Chevet E., Larose L. Modulation of protein translation by Nck-1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2002;99:5406–5411. doi: 10.1073/pnas.082483399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kebache S., Cardin E., Nguyen D. T., Chevet E., Larose L. Nck-1 antagonizes the endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced inhibition of translation. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:9662–9671. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310535200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meggio F., Pinna L. A. One-thousand-and-one substrates of protein kinase CK2? FASEB J. 2003;17:349–368. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0473rev. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Llorens F., Roher N., Miró F. A., Sarno S., Ruiz F. X., Meggio F., Plana M., Pinna L. A., Itarte E. Eukaryotic translation-initiation factor eIF2β binds to protein kinase CK2: effects on CK2α activity. Biochem. J. 2003;375:623–631. doi: 10.1042/BJ20030915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pathak V. K., Nielsen P. J., Trachsel H., Hershey J. W. Structure of the β subunit of translational initiation factor eIF-2. Cell (Cambridge, Mass.) 1988;54:633–639. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(88)80007-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gutierrez P., Osborne M. J., Siddiqui N., Trempe J. F., Arrowsmith C., Gehring K. Structure of the archaeal translation initiation factor aIF2β from Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum: implications for translation initiation. Protein Sci. 2004;13:659–667. doi: 10.1110/ps.03506604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hashimoto N. N., Carnevalli L. S., Castilho B. A. Translation initiation at non-AUG codons mediated by weakened association of eukaryotic initiation factor (eIF) 2 subunits. Biochem. J. 2002;367:359–368. doi: 10.1042/BJ20020556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Donahue T. F., Cigan A. M., Pabich E. K., Valavicius B. C. Mutations at a Zn(II) finger motif in the yeast eIF-2β gene alter ribosomal start-site selection during the scanning process. Cell (Cambridge, Mass.) 1988;54:621–632. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(88)80006-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Welsh G. I., Price N. T., Bladergroen B. A., Bloomberg G., Proud C. G. Identification of novel phosphorylation sites in the β-subunit of translation initiation factor eIF-2. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1994;201:1279–1288. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.1843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Issinger O. G., Benne R., Hershey J. W., Traut R. R. Phosphorylation in vitro of eukaryotic initiation factors IF-E2 and IF-E3 by protein kinases. J. Biol. Chem. 1976;251:6471–6474. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Benne R., Edman J., Traut R. R., Hershey J. W. Phosphorylation of eukaryotic protein synthesis initiation factors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1978;75:108–112. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.1.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ting N. S., Kao P. N., Chan D. W., Lintott L. G., Lees-Miller S. P. DNA-dependent protein kinase interacts with antigen receptor response element binding proteins NF90 and NF45. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:2136–2145. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.4.2136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Duncan R., Hershey J. W. Heat shock-induced translational alterations in HeLa cells: initiation factor modifications and the inhibition of translation. J. Biol. Chem. 1984;259:11882–11889. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Duncan R., Hershey J. W. Regulation of initiation factors during translational repression caused by serum depletion: covalent modification. J. Biol. Chem. 1985;260:5493–5497. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Garcia A. M., Martin M. E., Blanco L., Martin-Hidalgo A., Fando J. L., Herrera E., Salinas M. Effect of diabetes on protein synthesis rate and eukaryotic initiation factor activities in the liver of virgin and pregnant rats. Biol. Neonate. 1996;69:37–50. doi: 10.1159/000244277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Luis A. M., Izquierdo J. M., Ostronoff L. K., Salinas M., Santaren J. F., Cuezva J. M. Translational regulation of mitochondrial differentiation in neonatal rat liver: specific increase in the translational efficiency of the nuclear-encoded mitochondrial β-F1-ATPase mRNA. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:1868–1875. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Feng L., Yoon H., Donahue T. F. Casein kinase II mediates multiple phosphorylation of Saccharomyces cerevisiae eIF-2α (encoded by SUI2), which is required for optimal eIF-2 function in S. cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1994;14:5139–5153. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.8.5139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van den Heuvel J., Lang V., Richter G., Price N., Peacock L., Proud C. G., McCarthy J. E. The highly acidic C-terminal region of the yeast initiation factor subunit 2α (eIF-2α) contains casein kinase phosphorylation sites and is essential for maintaining normal regulation of GCN4. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1995;1261:337–348. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(95)00026-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mehta H. B., Dholakia J. N., Roth W. W., Parekh B. S., Montelaro R. C., Woodley C. L., Wahba A. J. Structural studies on the eukaryotic chain initiation factor 2 from rabbit reticulocytes and brine shrimp Artemia embryos: phosphorylation by the heme-controlled repressor and casein kinase II. J. Biol. Chem. 1986;261:6705–6711. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dholakia J. N., Xu Z., Hille M. B., Wahba A. J. Purification and characterization of sea urchin initiation factor 2: the requirement of guanine nucleotide exchange factor for the release of eukaryotic polypeptide chain initiation factor 2-bound GDP. J. Biol. Chem. 1990;265:19319–19323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Benne R., Wong C., Luedi M., Hershey J. W. Purification and characterization of initiation factor IF-E2 from rabbit reticulocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 1976;251:7675–7681. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Singh L. P., Arorr A. R., Wahba A. J. Phosphorylation of the guanine nucleotide exchange factor and eukaryotic initiation factor 2 by casein kinase II regulates guanine nucleotide binding and GDP/GTP exchange. Biochemistry. 1994;33:9152–9157. doi: 10.1021/bi00197a018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang X., Paulin F. E., Campbell L. E., Gomez E., O'Brien K., Morrice N., Proud C. G. Eukaryotic initiation factor 2B: identification of multiple phosphorylation sites in the ϵ-subunit and their functions in vivo. EMBO J. 2001;20:4349–4359. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.16.4349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Oldfield S., Proud C. G. Purification, phosphorylation and control of the guanine-nucleotide-exchange factor from rabbit reticulocyte lysates. Eur. J. Biochem. 1992;208:73–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1992.tb17160.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Singh L. P., Denslow N. D., Wahba A. J. Modulation of rabbit reticulocyte guanine nucleotide exchange factor activity by casein kinases 1 and 2 and glycogen synthase kinase 3. Biochemistry. 1996;35:3206–3212. doi: 10.1021/bi9522099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lebrin L., Chambaz E. M., Bianchini L. A role for protein kinase CK2 in cell proliferation: evidence using a kinase-inactive mutant of CK2 catalytic subunit α. Oncogene. 2001;20:2010–2022. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Channavajhala P., Seldin D. C. Functional interaction of protein kinase CK2 and c-Myc in lymphomagenesis. Oncogene. 2002;21:5280–5288. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Duncan R., Hershey J. W. Regulation of initiation factors during translational repression caused by serum depletion: abundance, synthesis, and turnover rates. J. Biol. Chem. 1985;260:5486–5492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lin R., Beauparlant P., Makris C., Meloche S., Hiscott J. Phosphorylation of IκBα in the C-terminal PEST domain by casein kinase II affects intrinsic protein stability. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1996;16:1401–1409. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.4.1401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang C., Vilk G., Canton D. A., Litchfield D. W. Phosphorylation regulates the stability of the regulatory CK2β subunit. Oncogene. 2002;21:3754–3764. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chiorini J. A., Boal T. R., Miyamoto S., Safer B. A difference in the rate of ribosomal elongation balances the synthesis of eukaryotic translation initiation factor (eIF)-2α and eIF-2β. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:13748–13755. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Majumdar R., Bandyopadhyay A., Deng H., Maitra U. Phosphorylation of mammalian translation initiation factor 5 (eIF5) in vitro and in vivo. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:1154–1162. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.5.1154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Maiti T., Bandyopadhyay A., Maitra U. Casein kinase II phosphorylates translation initiation factor 5 (eIF5) in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 2003;20:97–108. doi: 10.1002/yea.937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lin W. J., Tuazon P. T., Traugh J. A. Characterization of the catalytic subunit of casein kinase II expressed in Escherichia coli and regulation of activity. J. Biol. Chem. 1991;266:5664–5669. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.