Abstract

We consider whether disruption of a specific neural circuit related to self-regulation is an underlying biological deficit in borderline personality disorder (BPD). Because patients with BPD exhibit a poor ability to regulate negative affect, we hypothesized that brain mechanisms thought to be involved in such self-regulation would function abnormally even in situations that seem remote from the symptoms exhibited by these patients. To test this idea, we compared the efficiency of attentional networks in BPD patients with controls who were matched to the patients in having very low self-reported effortful control and very high negative emotionality and controls who were average in these two temperamental dimensions. We found that the patients exhibited significantly greater difficulty in their ability to resolve conflict among stimulus dimensions in a purely cognitive task than did average controls but displayed no deficit in overall reaction time, errors, or other attentional networks. The temperamentally matched group did not differ significantly from either group. A significant correlation was found between measures of the ability to control conflict in the reaction-time task and self-reported effortful control.

Kandel (1, 2) has argued that new concepts in neuroscience now make it possible to relate higher level cognition to brain systems, making contact with psychoanalytic concepts. Borderline personality disorder (BPD) is one mental health problem that has been identified and studied by psychoanalytic (3) as well as behaviorally oriented (4) therapists. Because of its complexity and lack of clear organic markers, BPD poses one of the greatest challenges to the goal suggested by Kandel's articles. As a first step in trying to make a translation between psychoanalytic and neuroscience concepts, we examine whether patients with BPD show a systematic deficit in a circuit known from neuroimaging studies to be involved in regulation of cognition and emotion.

BPD as defined in DSM IV involves a failure to integrate interpersonal relationships with the self-image, lability of affect, and impulsivity. There is no question about the devastating reality of behavioral problems of people diagnosed with BPD. Estimates of prevalence run from 0.3% to 1.8% in the adult population of the United States (5). Up to 75% of individuals diagnosed with BPD engage in self-destructive behavior such as self-mutilation (6) and suicide (7).

We began our efforts by hypothesizing that borderline patients would be high in negative affect and low in effortful control as measured by temperament and personality scales (8). These two constructs are related most closely to the overwhelming negative feelings and poor control of emotion and behavior that are at the heart of the borderline symptoms. A temperament high in negative emotionality (fear and anger) and low in effortful control would also seem to provide a basis for poor interpersonal relations, another of the central difficulties in BPD.

We chose to measure temperament with the adult temperament questionnaire (ATQ) (8), because (i) it included scales assessing negative affect and effortful control, and (ii) in children, effortful control as measured by a child form of the ATQ has been found to correlate with the ability to resolve conflict between stimulus dimensions (9). In adults, conflict tasks activate a common network of neural areas including the dorsal anterior cingulate and lateral prefrontal cortex, important for the control of cognition and emotion (10, 11).

Because a sense of conscience among children has been found to be related to effortful control (12) and BPD patients have problems with appropriate behavior in social settings, we speculated that there might be a specific disorder of mechanisms related to effortful control present in BPD patients that would generalize beyond the domain of interpersonal relations. To test this idea, we compared performance on the attention network test (ANT), a reaction-time (RT) task that was created to assess the efficiency of three attentional control networks (13). We studied patients diagnosed with BPD and two groups of controls. One group, the temperamentally matched controls, showed similar levels of negative affect and effortful control to the patients as measured by the ATQ (8). A second group, the average controls, showed mean levels on these two temperamental variables. We also correlated performance on effortful control as measured by the questionnaire with the efficiency of the executive attention network as measured by the ANT.

Methods

Participants.

Thirty-nine individuals in the New York area were diagnosed as having BPD by trained psychiatrists as part of a double-blind treatment study. The diagnosis involved 11 h of objective measures and interviews covering Axis I disorders [Structured Clinical Interview for Diagnosis (SCID), ref. 14] and Axis II disorders [International Personality Disorder Examination (IPDE), ref. 15].

In addition, we identified controls without known personality disorders from a sample of 1,000 students at Hunter College in New York City who completed the ATQ (ref. 8 and D.E.E. and M.K.R., unpublished data). The ATQ is a self-report questionnaire that asks subjects to read and rate 118 self-descriptive statements. Scores range from 1 to 7, with 4 representing the midpoint of the scale. The composite temperament scales of negative affect and effortful control were used to select two control groups for further study (see Table 1). All controls were also screened for personality disorders by using the international personality disorder examination (14). Only those without disorder are included in Table 1.

Table 1.

Group demographics

| Total N | Female | Male | Mean age, years | Median age, years | Minimum age, years | Maximum age, years | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BPD patients | 39 | 38 | 1 | 30 | 31 | 19 | 51 |

| Unmedicated BPD | 18 | 17 | 1 | 32 | 32 | 20 | 51 |

| Medicated BPD | 21 | 21 | 0 | 29 | 27 | 19 | 48 |

| Temperamentally matched controls | 22 | 20 | 2 | 20 | 19 | 18 | 35 |

| Average controls | 30 | 22 | 8 | 22 | 20 | 18 | 49 |

Procedure.

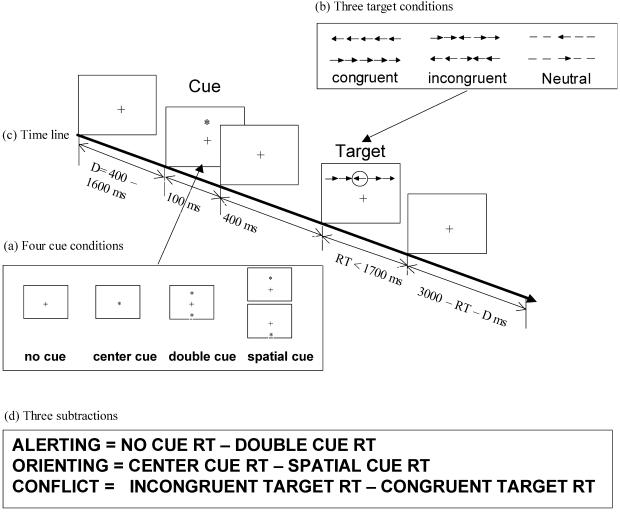

All participants completed the ANT (ref. 13; see also Fig. 1) to provide an evaluation of efficiency in three aspects of attention: alerting, orienting, and conflict resolution. Alerting is produced by a warning signal that contains no information about where the target will occur. Orienting is induced by a spatial cue that indicates where the target will be located. Conflict is produced by flankers surrounding the target that are incongruent with the target. Specific subtractions to obtain each measure are shown in Fig. 1d.

Fig 1.

ANT. (a) The cue conditions used in the experiment. (b) Three types of targets. (c) Time line for each trial. (d) Subtractions used to form network scores. [Reproduced with permission from ref. 13 (Copyright 2002, MIT Press Journals).]

The task was to press the left key if the central arrow pointed leftward and the right key if it pointed rightward. The target arrow was surrounded by flanker arrows that either pointed in the same direction (congruent) or the opposite direction (incongruent). One of four cue conditions was presented before the target: no cue, a double cue, a single cue at the location of the upcoming target, or a single central cue.

Each subject was given a total of 288 experimental trials, one fourth in each of the four cue conditions. Each trial began with either no cue or one of the three cues presented for 100 msec. The cue was followed after an average interval of 400 msec by a congruent, incongruent, or neutral target with equal frequency.

For all the persons described above and 40 additional persons for whom data were available on both the ATQ and ANT (131 persons total: 39 BPD patients, 22 temperamentally matched controls, and 70 unselected controls), we correlated performance on the ANT with scores on the effortful control measures of the ATQ. The effortful control measure involves questions dealing with the ability of people to exercise deliberate control of their behavior, thought, or emotion by activating or inhibiting relevant behaviors. For example, in a statement related to effortful control, people are asked to rate on a seven-point scale the degree to which each of the following are true of them: “I hardly ever finish things on time,” and “I can easily resist talking out of turn, even when I am excited and want to express an idea.” To study negative affect, participants rate statements such as “looking down at the ground from an extremely high place makes me feel uneasy,” and “I seldom become sad when I watch a sad movie.”

Results

Results of the effort to select temperamentally matched controls are shown in Table 2. The temperamental controls matched the patients in negative affect very closely and were even lower on effortful control than the patients. Medicated and nonmedicated BPD patients did not differ in temperament scores.

Table 2.

ATQ scores

| Negative affect | Effortful control | |

|---|---|---|

| BPD patients | 5.08 (0.60) | 3.51 (0.66) |

| Unmedicated BPD | 4.93 (0.48) | 3.59 (0.58) |

| Medicated BPD | 5.22 (0.67) | 3.44 (0.73) |

| Temperamentally matched controls | 5.07 (0.31) | 2.82 (0.43) |

| Average controls | 3.98 (0.13) | 4.03 (0.15) |

Standard deviation is shown in parentheses after each score.

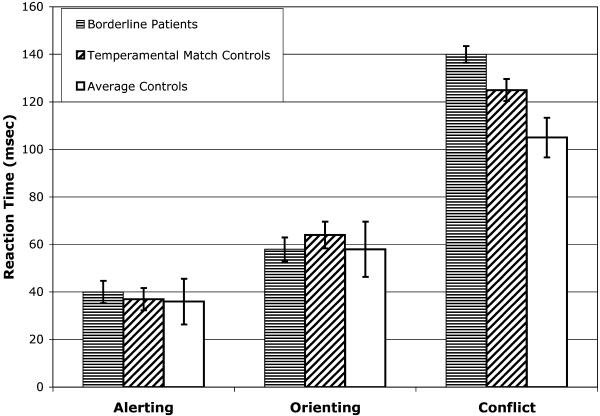

Results of the ANT task are shown in Table 3. ANOVAs showed highly significant effects of cue and target quite similar to what had been found in previous studies (13). These differences are reflected in the network scores shown in Table 3 and Fig. 2, which provide the result of the subtractions for alerting, orienting, and conflict (shown in Fig. 1d).

Table 3.

ANT RT, accuracy, and network scores for patients and controls

| Alerting mean | Orienting mean | Conflict mean | RT mean | Accuracy mean | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BPD patients | 40 (4.7) | 58 (4.7) | 140 (9.6) | 571 (13.7) | 0.976 (0.01) |

| Unmedicated BPD | 40 (8.7) | 55 (7.8) | 133 (15.1) | 584 (24.0) | 0.978 (0.01) |

| Medicated BPD | 40 (4.8) | 61 (5.8) | 147 (12.5) | 558 (15.1) | 0.974 (0.01) |

| Temperamentally matched controls | 37 (5.0) | 64 (5.6) | 125 (11.6) | 540 (13.2) | 0.973 (0.01) |

| Average controls | 36 (3.5) | 58 (4.6) | 105 (8.3) | 532 (11.6) | 0.977 (0.00) |

The standard error of the mean is shown in parentheses after each score.

Fig 2.

Network scores in terms of RT differences for alerting, orienting, and conflict for each of the three experimental groups.

There were no differences between groups in overall RT, error rate, or alerting or orienting network scores. In the conflict network score, there was a significant effect of group membership [F(2,88) = 3.57, P = 0.03]. Subsequent comparison by t test showed that the patients differed from average controls (P < 0.01) but did not differ significantly from temperamental controls. The temperamental control subjects had a somewhat larger conflict score than did the average controls and somewhat smaller than the patients. However, they did not show significant differences from either the average controls or the patients.

We evaluated whether the difference between patients and controls could be explained by differences in age or medication. It was possible that the medicated patients showed a somewhat larger effect, because they tend to have more severe symptoms than the unmedicated patients. Although the medicated patients showed a somewhat larger conflict score than unmedicated patients, this result was not significant [F(1,39) = 0.498]. Given the age differences between groups, we evaluated age as a predictor of conflict. Age and conflict scores were not significantly correlated for any of the groups. Thus the difference between patients and average controls was not because of age or medication.

To examine the relationship between network scores on the ANT and questionnaire scale scores, we calculated conflict scores (RT for incongruent − congruent trials) for each subject and divided by the overall RT to reduce the influence of overall RT. We then correlated these adjusted conflict scores with effortful control as measured by the ATQ. We found a significant negative correlation of −0.29 (P < 0.01). All the subscales related to effortful control were also related to the conflict scores of the ANT. This replicated a finding that had been reported in young children (9). We also replicated the usual finding that effortful control was negatively related to reported negative affect r = −0.68 (P < 0.01) (16).

Discussion

The results obtained indicate two important findings about BPD. First, there seems to be a specific abnormality in BPD patients in an attentional network involved in conflict resolution and more generally in cognitive control. This was found even though the ANT is a purely cognitive task, remote from the emotional symptoms related to BPD. No other attentional network seems to be impaired in these patients.

Second, the abnormality as measured by the ANT is definitely present only in the patients. Although the temperamental controls are also elevated in conflict score, they are not significantly different from the average controls despite having lower average effortful control values than the patients. These findings are congruent with a number of hypotheses about the etiology of the disorder. One is the idea that temperament plays a role in the disorder, possibly in predisposing an individual to develop it. We have examined several polymorphisms in candidate genes known to influence the conflict network (17), but thus far we have not able to detect any abnormal frequencies in the patients (18). In the full sample of patients studied at the Department of Psychiatry (Westchester Division of Weill Medical College), 71% reported emotional abuse, 38% physical abuse, and 28% sexual abuse. These and other aspects of socialization might act together with a lack of effortful control to produce the other symptoms. Another possibility is that the difficulties in socialization themselves may produce an inappropriate development of attentional mechanisms for the control of cognition and emotion.

Although the attentional deficit found in BPD patients is not likely to be confined to this group, the fact that it involves a specific attentional network provides important information on the anatomy of the deficit. Neuroimaging studies have shown that an important part of the conflict network involves the anterior cingulate gyrus (10, 11, 19). There is evidence of the development of this network between ages 2 and 7 years, as indicated in the performance on a spatial conflict task inducing conflict between identity and location, two of the earliest developing visual-system operations (9). In adults, this spatial conflict task activates the dorsal cingulate in an area similar to the one activated by the color Stroop and in the flanker task as used in the ANT (11). There are significant correlations between children's performance on the spatial conflict task and parental reports of effortful control (9, 20). The current data show a similar correlation in adults.∥

Work with a child version of the ANT suggests that development in the network underlying the ability to deal with conflict continues up to age 7 but not after that age.** A striking feature of children over the developmental period from age 2 to 7 is an increase in their ability to regulate their cognition and emotion. Moreover, during this period, abusive events, which have also been related to BPD, may be likely to influence the developing attentional system (3). It is useful therefore to consider what is known about the normal development of attention and effortful control at these ages.

Studies of effortful control (21) and the conflict network (22) both have found substantial heritability. In addition, empathy with others is strongly related to effortful control, with children high in effortful control showing greater empathy (23). To display empathy toward others requires that we interpret their signals of distress or pleasure. Lack of empathy may help to produce the kind of difficulty with interpersonal relations found in BPD. Recently it was found that both effortful control and conflict as measured by the ANT aided in the prediction of antisocial outcomes in adolescence (L. Ellis, unpublished data). In children (24) and adults (25), lesions of the medial frontal areas including the dorsal anterior cingulate produce the tendency toward poor interpersonal relations and more generally antisocial behavior. Consistent with its influence on empathy, effortful control also seems to play a role in the development of conscience (26). These findings make it plausible that the temperamental characteristics of BPD patients could predispose them to difficulties in socialization.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the Borderline Personality Disorder Research Foundation.

Abbreviations

BPD, borderline personality disorder

ATQ, adult temperament questionnaire

ANT, attention network test

RT, reaction time

In unpublished adult studies using the ANT and ATQ we had not found significant correlations between conflict scores and effortful control. The finding of a significant correlation in this study might be due to a larger range of scores when including results from BPD patients and temperamentally matched controls who are relatively low in effortful control as well as advanced students who were relatively high in effortful control. A large range of performance might be important in obtaining the correlation.

Rueda, M. R., Fan, J., McCandliss, B., Halparin, J., Gruber, D., Pappert, L. & Posner, M. I. (2002) Cognit. Neurosci. Soc. Suppl., 21 (abstr.).

References

- 1.Kandel E. R. (1998) Am. J. Psychiatry 155, 457-469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kandel E. R. (1999) Am. J. Psychiatry 56, 504-524. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kernberg P. F., Weiner, A. S. & Bardenstein, K. K., (2000) Personality Disorders in Children and Adolescents (Basic Books, New York).

- 4.Linehan M. M., (1993) Cognitive Behaviorial Treatment of Borderline Personality Disorder (Guilford, New York).

- 5.Lenzenweger M. F., Loranger, A. W., Korfine, L. & Neff, C. (1997) Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 54, 345-351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clarkin J. F., Widiger, T., Frances, A., Hurt, S. W. & Gilmore, M. (1983) J. Abnorm. Soc. Psychol. 92, 263-275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McGlashan T. H. (1986) Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 43, 20-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rothbart M. K., Ahadi, S. A. & Evans, D. E. (2002) J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 78, 122-135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gerardi-Caulton G. (2000) Dev. Sci. 3/4, 397-404. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bush G., Luu, P. & Posner, M. I. (2000) Trends Cogn. Sci. 4/6, 215-222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fan, J., Flombaum, J. I., McCandliss, B. D., Thomas, K. M. & Posner, M. I. (2002) Neuroimage, in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Kochanska G. (1997) Dev. Psychol. 3, 228-240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fan J., McCandliss, B. D., Sommer, T., Raz, M. & Posner, M. I. (2002) J. Cognit. Neurosci. 3, 340-347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.First M. B., Gibbon, M., Spitzer, R. L. & Williams, J. B. W., (1996) User's Guide for the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IVAxis I-Research Version (Am. Psychiatr. Press, Washington, DC), Version 2.

- 15.Loranger A. W., (1999) International Personality Disorder Examination (Psychol. Assess. Resources, Odessa, FL).

- 16.Derryberry D. & Rothbart, M. K. (1988) J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 55, 953-966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fossella J., Sommer, T., Fan, J., Wu, Y., Swanson, J. M., Pfaff, D. W. & Posner, M. I. (2002) BMC Neurosci. 3, 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Posner, M. I., Rothbart, M. K., Vizueta, N., Thomas, K. M., Levy, K., Fossella, J., Silbersweig, D. A., Stern, E., Clarkin, J. & Kernberg, O. (2002) Dev. Psychopathol., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Beauregard M., Levesque, J. & Bourgouin, P. (2001) J. Neurosci. 21, RC165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rothbart, M. K., Ellis, L. & Posner, M. I. (2002) J. Pers., in press.

- 21.Goldsmith H. H., Lemery, K. S., Buss, K. A. & Campos, J. J. (1999) Dev. Psychol. 35, 972-985. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fan J., Wu, Y., Fossella, J. & Posner, M. I. (2001) BioMed. Central Neurosci. 2, 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rothbart M. K., Ahadi, S. A. & Hershey, K. (1993) Merrill Palmer Q. 40, 21-39. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Anderson S. W., Damasio, H., Tranel, D. & Damasio, A. R. (2000) Dev. Neuropsychol. 18, 281-296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Damasio A., (1994) Human Brain (Putnam, New York).

- 26.Kochanska G., Murray, K., Jacques, T. Y., Koenig, A. L. & Vandegeest, K. A. (1996) Child Dev. 67, 490-507. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]