Abstract

The degree of acyl chain desaturation of membrane lipids is a critical determinant of membrane fluidity. Temperature-sensitive mutants of the single essential acyl chain desaturase, Ole1p, of yeast have previously been isolated in screens for mitochondrial inheritance mutants (Stewart, L.C., and Yaffe, M.P. (1991). J. Cell Biol. 115, 1249–1257). We now report that the mutant desaturase relocalizes from its uniform ER distribution to a more punctuate localization at the cell periphery upon inactivation of the enzyme. This relocalization takes place within minutes at nonpermissive conditions, a time scale at which mitochondrial morphology and inheritance is not yet affected. Relocalization of the desaturase is fully reversible and does not affect the steady state localization of other ER resident proteins or the kinetic and fidelity of the secretory pathway, indicating a high degree of selectivity for the desaturase. Relocalization of the desaturase is energy independent but is lipid dependent because it is rescued by supplementation with unsaturated fatty acids. Relocalization of the desaturase is also observed in cells treated with inhibitors of the enzyme, indicating that it is independent of temperature-induced alterations of the enzyme. In the absence of desaturase function, lipid synthesis continues, resulting in the generation of lipids with saturated acyl chains. A model is discussed in which the accumulation of saturated lipids in a microdomain around the desaturase could induce the observed segregation and relocalization of the enzyme.

INTRODUCTION

The degree of acyl chain desaturation of membrane lipids comprises the most effective modulator of the biophysical properties of cellular membranes. In pure phospholipid bilayers, the substitution of a saturated (SFA) by a monounsaturated fatty acid (UFA) reduces the gel to liquid-crystalline phase transition temperature by up to 45°C (Cullis et al., 1996). This dramatic reduction in the phase transition temperature is most effective if the cis-double bond is located in the middle of the acyl chain, between carbon atoms 9 and 10, where it is found naturally. ,

The committed step in the biosynthesis of monounsaturated fatty acids is the introduction of the first double bond in the Δ-9 position of the acyl chain. This reaction is catalyzed by a nonheme iron–containing enzyme, which requires cytochrome b5, NADH-cytochrome b5 reductase, and molecular oxygen. The fatty acid desaturases that catalyze this reaction can be divided into two evolutionary distinct classes, soluble and integral membrane enzymes (Los and Murata, 1998).

The major UFAs in yeast are palmitoleic (C16:1) and oleic (C18:1) acid, which together account for ∼70% of the total fatty acid content. They are synthesized by desaturation of either de novo produced SFAs or after uptake and activation of exogenously supplied fatty acids. Desaturation is catalyzed by a single essential Δ-9 desaturase encoded by the OLE1 gene (Stukey et al., 1989, 1990). The activity of the desaturase is tightly regulated at several different levels by UFA levels (Bossie and Martin, 1989). For example, steady state levels of OLE1 mRNA sharply decline upon addition of UFAs by a mechanism that is sensitive to the position of the double bond and that involves both transcriptional and posttranscriptional regulation of OLE1 mRNA synthesis and stability (McDonough et al., 1992; Gonzalez and Martin, 1996; Choi et al., 1996). Conversely, overexpression of OLE1 is toxic and results in a reduced growth rate and abnormal cell division (Stukey et al., 1989).

More recently, a regulated ubiquitin- and proteasome-dependent activation of two membrane-bound transcription factors, Spt23p and Mga2p, has been shown to control OLE1 transcription in response to membrane fluidity (Hoppe et al., 2000; Rape et al., 2001). This proteolytical activation of membrane-bound transcription factors in yeast is reminiscent of the mechanism that control sterol homeostasis in mammalian cells (Brown and Goldstein, 1999).

The yeast desaturase is an integral membrane protein with a cytochrome b5-like domain at its carboxy terminus (Stukey et al., 1990; Mitchell and Martin, 1995). Mutations in OLE1 have been isolated during the late 1960s in screens for oleic acid auxotrophic mutants (Resnick and Mortimer, 1966). More recently, conditional temperature-sensitive (ts) mutations of OLE1 have been isolated in screens for mutants that fail to transmit mitochondria from the mother cell to the growing bud (McConnell et al., 1990; Stewart and Yaffe, 1991; Hermann et al., 1997). Analysis of one of these mutants, mdm2, revealed that reduced levels of UFAs result in a severe perturbation of cellular membranes, most notably of the nuclear envelope and of mitochondria (Stewart and Yaffe, 1991; Schneiter and Kohlwein, 1997; Zhang et al., 1999).

We were interested in determining the immediate early consequences of a block in acyl chain desaturation. Using fusions of wild-type and conditional desaturase mutant alleles with the green fluorescent protein (GFP), we report that the mutant desaturase segregates away from other ER resident proteins within minutes of a shift to nonpermissive conditions. The biochemical, genetic, and morphological characterization of this segregation event is consistent with the proposal that it reflects a lipid-dependent process. A model is discussed in which the accumulation of lipids with saturated acyl chains induces the observed relocalization.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and Growth Conditions

Yeast strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. Strains were cultivated at 30 or 37°C in YPD rich media (1% Bacto yeast extract, 2% Bacto peptone [Difco Laboratories Inc., Detroit, MI], 2% glucose) or minimal media. Media supplemented with fatty acids contained 1% Brij 58, and either 0.5 mM palmitoleic together with 0.5 mM oleic acid as UFA supplements or 0.5 mM palmitic acid together with 0.5 mM stearic acid as SFA supplements (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO). For DNA cloning and propagation of plasmids Escherichia coli strain XL1-blue (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) was used throughout this study.

Table 1.

S. cerevisiae strains used in this study

| Strain | Relevant genotype | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| RH1961 | MATa his4 leu2 ura3 emp24∷LEU2 | Schimmöller et al. (1995) |

| W303 | MATa ade2 his3 leu2 trp1 ura3 | R. Rothstein, laboratory strain collection |

| JSY307 | MATα leu2 ura3 | Hermann et al. (1997) |

| UV3381 | MATα leu2 ura3 ole1ts-2 | Hermann et al. (1997) |

| YRS1327 | MATa ade1 ade2 his7 leu2 lys2 ura3 ole1ts | Stewart and Yaffe (1991) |

| YRS1345 | MATα ade2 his3 leu2 ura3 ole1∷LEU2 | Stukey et al. (1989) |

| YRS1346 | MATα ade2 his3 leu2 ura3 ole1∷LEU2 p[OLE1 LEU2] | This study |

| YRS1347 | MATα ade2 his3 leu2 ura3 ole1∷LEU2 p[OLE1ts LEU2] | This study |

| YRS1348 | MATα ade2 his3 leu2 ura3 ole1∷LEU2 p[OLE1-myc LEU2] | This study |

| YRS1349 | MATα ade2 his3 leu2 ura3 ole1∷LEU2 p[OLE1ts-myc LEU2] | This study |

| YRS1315 | MATa ade2 his3 leu2 lys2 trp1 ura3 OLE1-GFP-KanMX6 | This study |

| YRS1314 | MATa ade1 ade2 his7 leu2 lys2 ura3 ole1ts-GFP-KanMX6 | This study |

| YRS1322 | MATα leu2 ura3 ole1ts-2-GFP-KanMX6 | This study |

| YRS1333 | MATa ade2 his3 leu2 trp1 ura3 p[SEC63-GFP URA3] | This study |

| YRS1342 | MATa ade1 ade2 his7 leu2 lys2 ura3 ole1tsp[SEC63-GFP URA3] | This study |

| YRS1568 | MATα leu2 ura3 OLE1-PrA-KanMX4 | This study |

| YRS1569 | MATα leu2 ura3 ole1ts-2-PrA-KanMX4 | This study |

| YRS1000 | MATa ade2 his3 leu2 ura3 ole1tsp[COX4-GFP HIS3] | This study |

| YRS1357 | MATα his3 leu2 trp1 lys2 suc2-Δ9 sed5-1 ole1ts-GFP-KanMX6 | This study |

| YRS1353 | MATα ade2 his3 leu2 trp1 ura3 ufe1∷TRP1 ole1ts-GFP-KanMX6 p[ufe1-1 LEU2] | This study |

Plasmid Constructions

To clone the wild-type and mutant alleles of the desaturase, the genes were PCR-amplified from genomic DNA using primers Ole1p05 and Ole1p06 (see Table 2 for sequence of oligonucleotides). Amplified fragments were cut with ApaI and PstI and ligated into the corresponding sites of pRS315 (Sikorski and Hieter, 1989) to generate pOLE1 and pOLE1ts. Restriction and ligation of DNA fragments, preparation of plasmid DNA, elution of DNA from low-melt agarose gels, and transformation of lithium acetate competent yeast cells was performed according to established procedures.

Table 2.

Primers used in this study

| Primer | Sequence |

|---|---|

| Ole1p05 | GCGAGCTATTTCGGGTATCC |

| Ole1p06 | AATTGTCGGTGGGAGTTATCA |

| p-myc1 | CATGCGAACAAAAGCTTATTTCTGAAGAAGACTTGG |

| p-myc2 | GCTTGTTTTCGAATAAAGACTTCTTCTGAACCGTAC |

| p-GFP1 | TTAGAATGGCTAGTAAGAGAGGTGAAATCTACGAAACTGGTAAGTTCTTTGGAGCAGGTGCTGGTGCT GGTGCTGGAGCA |

| p-GFP2 | GGTTACTGTATAAATGTACATATAAATATTTGTATAGTTAGTATGCCATATCAATCGATGAATTCGAGC TCGTTTAAAC |

| p-GFP4 | GGTCAATTTACCGTAAGTAGC |

| pOLE1-S2 | GGTTACTGTATAAATGTACATATAAATATTTGTATAGTTAGTATGCCATAATCGATGAATTCGAGCTCG |

| pOLE1-S3 | TTAGAATGGCTAGTAAGAGAGGTGAAATCTACGAAACTGGTAAGTTCTTTCGTACGCTGCAGGTCGAC |

| pKan+His | TGGGCCTCCATGTCGCTG |

| OLE1p13 | CTTGGCTAAGTCTAAGGA |

Myc-epitope tagging of the desaturase was performed by ligating the annealed oligonucleotides p-myc1 and p-myc2 into NcoI-cleaved pOLE1 and pOLE1ts to generate pOLE1-myc and pOLE1ts-myc. Correct insertion of the linker was confirmed by restriction enzyme analysis and DNA sequencing. Sequencing was performed on an ABI 373A sequencer using the ABI PRISM BigDye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Ready Reaction Kit with AmpliTaq DNA Polymerase (PE Perkin Elmer-Cetus, Foster City, CA).

Generation of GFP- and Protein A–tagged Desaturase Alleles

Plasmid pMK199 GA5-EGFP, kindly provided by P. Philippsen (Biocenter University Basel, Switzerland; Wach et al., 1997), was used for PCR amplification of an integrative EGFP-KanMX6 fusion cassette using primers p-GFP1 and p-GFP2. Plasmid pYM9, kindly provided by E. Schiebel (The Beatson Institute for Cancer Research, Glasgow, UK; Knop et al., 1999) was used to amplify an integrative PrA-KanMX6 fusion cassette using primers pOLE1-S2 and pOLE1-S3. Purified PCR-fragments were transformed into wild-type and ts mutant strains. Correct integration of the fusion cassette immediately 5′ of the stop codon of OLE1 was confirmed by PCR amplification using primer pairs OLE1-p13/p-GFP4 and OLE1-p13/pKan+His.

Immunofluorescence and In Vivo Localization of Proteins

Indirect immunofluorescence was performed using mouse anti-myc (1:80; Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Indianapolis, IN) and rabbit anti-Kar2p (1:100; kindly provided by M. Rose, Princeton University, NJ) primary antibodies. Secondary antibodies used were FITC-conjugated anti-mouse, and lissamine-rhodamine (LRSC)-conjugated anti-rabbit (1:200; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc., West Grove, PA). For the in vivo localization of GFP-tagged proteins, early logarithmic cells were harvested, stained with DAPI (4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole), and immediately examined using a Leica TCS 4d confocal microscope (Deerfield, IL) equipped with a PL APO 100×/1.40 objective.

Electron Microscopy

Wild-type and mutant cells were grown to midlogarithmic phase in rich medium with or without the supplementation of UFAs. Cells were shifted to 37°C for 15 min and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde-5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer, pH 7.0, containing 1 mM CaCl2 for 90 min, incubated for 1 h in a 2% solution of KMnO4, and further processed for electron microscopy.

For cryo-fixation and freeze substitution, cells were transferred onto small paper stripes or copper grids and cryo-fixed by plunge freezing into liquid propane (Leica KF 80). The frozen specimens were transferred to a cryotube containing 1.5 ml 2% osmium tetroxide, 0.2% uranyl acetate in 100% acetone for freeze substitution. The substitution was carried out for 4 d at −85°C, for 1 d at −60°C, and for 1 d at −30°C. Samples were warmed up to room temperature over a 12-h period, washed three times for 10 min in 100% acetone, and embedded in LR White.

For immunogold labeling, cells were fixed for 90 min at room temperature in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer (pH 7.0) containing 4% formaldehyde, 0.5% glutaraldehyde, 1 mM CaCl2, and 1 mM MgCl2. The cells were washed in buffer containing 1 mM CaCl2 and 1 mM MgCl2 for 1 h and incubated in 1% sodium metaperjodate for 15 min followed by incubation in 50 mM ammonium chloride for 15 min. After washing with distilled H2O for 15 min, the samples were dehydrated in a graded series of ethanol (50–100%) and embedded in LR White. For antibody staining, ultrathin sections were collected on nickel grids and incubated for 20 min in TBS-BSA (8 mM Na2HPO4, 1.5 mM KH2PO4, 140 mM NaCl, 3 mM KCl, and 2% BSA, pH 8.0). Grids were incubated for 2 h with the primary monoclonal anti-PrA antibody (1:10; Sigma Chemical Co.). After several washes, the grids were incubated for 90 min with the goat anti-mouse IgG secondary antibody conjugated to 10 nm colloidal gold (1:50; British BioCell Int. Ltd., Cardiff, United Kingdom). After washing in TBS followed by distilled water, the grids were poststained with lead citrate and uranyl acetate. The specificity of immunolabeling reaction was assessed by omitting the primary antibody.

Subcellular Fractionation and Western Blot Analysis

Western blot analysis using mouse anti-myc (1:200; Roche Molecular Biochemicals), mouse anti-GFP (1:5000; Roche Molecular Biochemicals), mouse anti-ALP (2 μg/ml; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR), rabbit anti-Kar2p (1:200; M. Rose, Princeton University), rabbit anti-Wbp1p (1:1000; M. Aebi, ETH-Zurich, Switzerland), rabbit anti-Gas1p (1:2000; H. Riezman, Biocenter, University of Basel, Switzerland), rabbit anti-Pma1p (1:1000; G. Daum, Graz University of Technology), or rabbit antiporin (1:20,000; G. Daum), was performed as described by Schneiter et al. (1999).

Microsomes were isolated from cells grown in YPD media at 30°C to an OD600 nm of ∼1 as described by Schneiter et al. (1999). Protein concentration of the different fractions was determined by the method of Lowry et al. (1951), using BSA as standard.

Detergent and salt extraction of microsomes was performed by incubating 50 μg of the microsomal fraction with 1% Triton X-100, 1 M NaCl or 0.1 M Na2C03 for 30 min on ice. Samples were centrifuged at 30,000 × g for 30 min. Pellet and supernatant fractions were then analyzed by Western blot. For the proteinase K protection experiment, microsomes (50 μg) were incubated with 9, 14, or 28 μg/ml proteinase K for 30 min on ice. The reaction was stopped by the addition of PMSF (5 mM), and proteins were precipitated with TCA (10%). The pellet was dissolved in 100 μl sample buffer and heated to 95°C for 10 min, and 10 μl was subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis.

Fractionation on Accudenz gradients (Accurate Chemical and Scientific Corp, Oslo, Norway) was performed as described by Cowles et al. (1997). Fourteen fractions were collected from the bottom of the gradient, and protein was precipitated with 10% TCA and detected by Western blot analysis.

For protein cross-linking, cells expressing the GFP-tagged mutant desaturase were incubated either with 20 mM NaN3 or with water for 15 min, and cells were resuspended in PBS (150 mM NaCl, 20 mM Na-phosphate, pH 7.5) containing protease inhibitors (Protease inhibitor; Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany), supplemented with 1 mM PMSF, 1 mg/ml pepstatin A, and 1 mg/ml leupeptin, and homogenized with glass beads in a Merckenschlager homogenizer under CO2 cooling. The lysate was cleared twice and incubated with either DMSO, or the membrane-permeable cross-linker dithiobis (succinimidylpropionate) (DSP; Pierce, Rockford, IL) dissolved in DMSO (1 mM or 0.06 mM), for 2 h on ice. The reaction was terminated by the addition of 50 mM Tris, pH 7.9, for 15 min at 4°C. The lysate was then adjusted to 0.5% Triton X-100 and 0.5% SDS and loaded on a sucrose gradient (5–40%) in PBS containing 0.5% Triton and 0.5% SDS. After centrifugation at 215,000 × g for 16 h, 12 fractions were collected from the bottom of the gradient, and protein was precipitated with 10% TCA. To cleave the cross-linker, proteins were resuspended in sample buffer containing 50 mM DTT and incubated for 30–60 min at 37°C, and proteins were detected by Western blot analysis.

Detergent resistant membranes were isolated by floatation on Optiprep gradients (Axis Shield PoC AS, Oslo, Norway) as described by Bagnat et al. (2000).

Protein Maturation and Secretion Assays

Secretion of invertase was assayed as follows. Cells were grown in minimal media containing 5% glucose to an OD600 nm of 0.2. Invertase expression was induced by resuspending the cells in low-glucose media (0.05%), and the cultures were preshifted to 37°C for 15 min. Samples were then removed at the indicated time points, and cells were metabolically poisoned by the addition of 10 mM NaN3. Invertase activity of equal number of cells was determined as described by Goldstein and Lampen (1975). Gas1p and carboxypeptidase Y (CPY) maturation was analyzed as described by Munn et al. (1999), and Kar2p secretion was monitored as described by Elrod-Erickson and Kaiser (1996).

Lipid Labeling, Extraction, and Analysis

Fatty acid composition was determined as previously described (Schneiter et al., 1996). To follow lipid synthesis and to determine the in vivo activity of mutant and wild-type desaturase, strains were cultivated in liquid minimal media to the midlogarithmic growth phase. Fifty OD600 nm units of cells were collected, resuspended in fresh media, and preincubated for 30 min. Cells were then pulse-labeled by the addition of 1 μCi [14C]palmitic acid (NEN, Boston, MA) for 15 min at 30 or 37°C. Labeling was terminated by the addition of 10 mM NaN3, cells were broken with glass beads in a Merckenschlager homogenizer, and lipids were extracted and analyzed as previously described by Wagner and Paltauf (1994).

RESULTS

Molecular Characterization of ole1ts/mdm2, Epitope-tagging, and Subcellular Localization of the Desaturase

To identify the sequence alteration that results in the conditional phenotype of the previously described ts allele of OLE1, mdm2 (Stewart and Yaffe, 1991; hereafter referred to as ole1ts), wild-type and mutant alleles were amplified by PCR and cloned into the centromere-containing vector pRS315 (Sikorski and Hieter, 1989). The resulting plasmids, pOLE1 and pOLE1ts, complemented the fatty acid auxotrophy of the ole1Δ mutant strain, and in the case of pOLE1ts conferred an UFA-dependent ts growth phenotype to ole1Δ (unpublished data). Sequence analysis of mutant and wild-type alleles revealed a single cytosine to thymine exchange in the ts mutant, which results in the substitution of an alanine by a valine residue at position 484 (A484V) in the C-terminal cytochrome b5-like domain of the protein. This substitution affects an evolutionary nonconserved residue of this domain (Meesters et al., 1997).

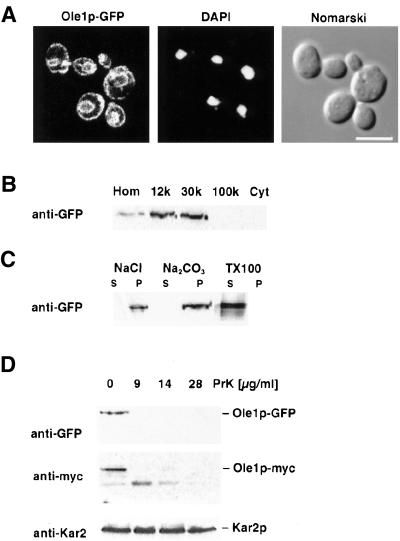

To examine the subcellular localization and membrane topology of the desaturase, an myc epitope was introduced before the first putative transmembrane domain of the enzyme as described in MATERIALS AND METHODS, and GFP was fused to the C terminus of the enzyme. These tagged versions of wild-type and mutant desaturase alleles were fully functional as judged by the robust growth of the respective strains on media without UFAs. In vivo localization of the GFP-tagged desaturases by fluorescence microscopy revealed a staining pattern characteristic of the yeast ER, with intense labeling of both perinuclear and cortical ER domains (Preuss et al., 1991; Prinz et al., 2000; Figure 1A). Immunofluorescence analysis of the myc-tagged alleles revealed a localization similar to that observed for the GFP-tagged versions (unpublished data).

Figure 1.

Subcellular localization and fractionation properties of the desaturase. (A) Fluorescence microscopy of cells expressing the GFP-tagged desaturase. Strain YRS1315 was grown to early logarithmic phase and prepared for fluorescence microscopy. In vivo localization of Ole1p-GFP reveals a staining pattern characteristic of the yeast ER. DAPI staining of nuclei and Nomarski view of the corresponding visual field are shown to the right. Bar, 5 μm. (B) Subcellular fractionation of the GFP-tagged desaturase. Strain YRS1315 was grown to midlogarithmic phase, harvested and fractionated into 12,000 × g (12k), 30,000 × g (30k), and 100,000 × g (100k) pellets and a 100,000 × g supernatant (Cyt). Protein, 10 μg, from each fraction was separated by SDS-PAGE, blotted, and probed with an anti-GFP antibody. Hom, homogenate. (C) Solubilization properties of the GFP-tagged desaturase. Microsomes of strain YRS1315 were incubated with 1 M NaCl, 0.1 M Na2CO3, or 1% Triton X-100 for 30 min on ice and then centrifuged for 30 min at 30,000 × g. Protein from the supernatant (S) and the pellet (P) fractions were subjected to Western blot analysis using an anti-GFP antibody. (D) Membrane topology of the desaturase. Microsomes of strains expressing either the GFP (YRS1315) or the myc-tagged desaturase (YRS1348) were incubated with increasing concentrations of proteinase K (PrK) for 30 min on ice. The reaction was stopped and products were analyzed on Westerns blots probed with anti-GFP or anti-myc antibodies. Membranes were reprobed with an antibody against Kar2p to assess the integrity of the microsomal membranes. The positions of full length Kar2p, GFP-, and myc-tagged Ole1p are indicated to the right.

The Desaturase is an Integral Membrane Protein with Both Termini in the Cytosol

To confirm the ER localization of the desaturase, cells expressing the GFP-tagged version were fractionated by differential centrifugation. This analysis revealed a 2.6-fold enrichment of the desaturase in the 12,000 × g pellet and 2.9-fold enrichment in the 30,000 × g microsomal pellet, which is consistent with an ER localization of the protein (Figure 1B). The desaturase was solubilized by treatment with Triton X-100 but not by NaCl or Na2CO3, indicating that Ole1p is an integral membrane protein of the ER (Stukey et al., 1990; Figure 1C).

The desaturase is predicted to contain either three or four transmembrane domains, depending on the algorithm used. To determine the membrane topology experimentally, microsomes isolated from cells that express either the C-terminal GFP fusion or the N-terminal myc-epitope–tagged version of the desaturase were treated with increasing concentrations of proteinase K, and the cleavage products were analyzed by Western blot. This examination revealed that both termini of the desaturase were accessible to cleavage by proteinase K. At the same time, Kar2p, a soluble lumenal resident of the ER, was protected from degradation, indicating that the membrane seal remained intact (Figure 1D). Taken together, these results indicate that the desaturase is an integral membrane protein of the ER with four transmembrane domains and both N and C termini in the cytosol, which is in agreement with the recently determined topology of a plant orthologue of Ole1p (Dyer and Mullen, 2001).

Nonpermissive Conditions Induce a Rapid and Reversible Relocalization of the Mutant Enzyme

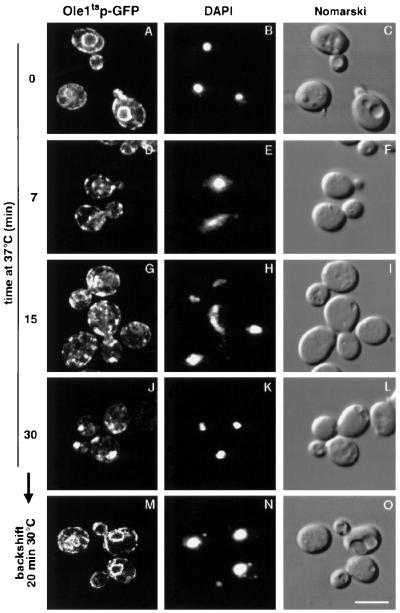

To examine the fate of the mutant enzyme under nonpermissive conditions, the subcellular distribution of the GFP-tagged desaturase was analyzed by fluorescence microscopy. After a shift to nonpermissive conditions for 7 min, the mutant desaturase changed its subcellular localization, as indicated by the transition of the circular ER staining to a more punctuate pattern (Figure 2). On longer incubations at 37°C, the number of punctuate fluorescent spots decreased, whereas the intensity and size of the remaining spots increased. This transition in size and intensity of the fluorescent signal appeared to be accompanied by a general peripheralization of the punctuate structures because the later appearing large fluorescent spots were typically localized at the cell periphery.

Figure 2.

Subcellular relocalization of the mutant desaturase in cells shifted to nonpermissive conditions. The strain expressing Ole1tsp-GFP (YRS1314) was cultivated at 30°C to early logarithmic phase and shifted to 37°C for 0, 7, 15, or 30 min. The characteristic ER staining observed under permissive conditions (A) converts to a more punctuate pattern in cells shifted to nonpermissive conditions (D, G, and J). Shifting cells from 37°C (30 min) back to 30°C for 20 min restores ER localization of the desaturase in the presence of cycloheximide (10 μg/ml) (M). DAPI staining of nuclei and Nomarski view of the corresponding visual fields are shown to the right. Bar, 5 μm.

The subcellular relocalization of the mutant desaturase was also observed in cells treated with cycloheximide, indicating that it is independent of ongoing protein synthesis. Relocalization of the mutant desaturase was independent of the C-terminal tag, because it was also observed by immunofluorescence microscopy of the myc-tagged version. Relocalization, however, was specific for the mutant enzyme, because it was not observed when cells expressing either myc- or GFP-tagged wild-type alleles were incubated at 37°C (unpublished data). This relocalization of the mutant enzyme was observed in the majority of cells examined (>80%, unpublished data). To determine whether the relocalization of the mutant desaturase is reversible, cells were shifted from nonpermissive conditions back to permissive conditions. Remarkably, a backshift to 30°C for 20 min fully restored ER localization of the mutant enzyme in the presence of cycloheximide (Figure 2M).

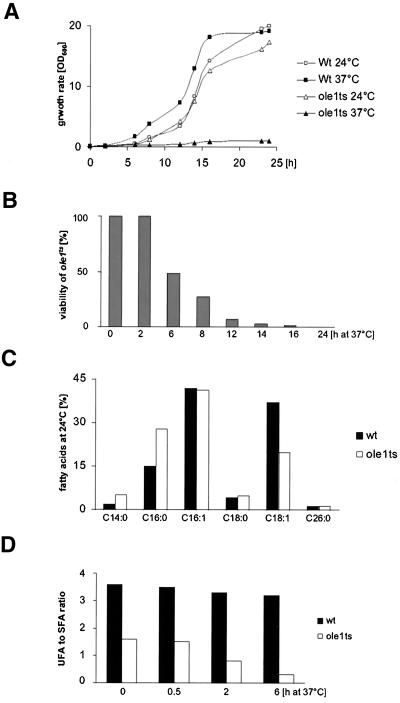

Viability and Fatty Acid Composition of the Desaturase Mutant

To characterize the desaturase mutant in more detail, we first examined the growth rate of mutant and wild-type cells. At permissive conditions the desaturase mutant strain had a growth rate comparable to wild-type cells. Under nonpermissive conditions growth of the mutant ceased rapidly (Figure 3A). To determine whether the temperature arrest was reversible, viability of the mutant after a shift to nonpermissive conditions was compared with that of wild-type cells. The desaturase mutant remained fully viable at nonpermissive conditions for 2 h. After longer incubations at 37°C, the viability of the mutant steadily declined to below 1% after 24 h (Figure 3B). Analysis of the fatty acid composition of the desaturase mutant at permissive conditions revealed elevated levels of the saturated C14 and C16 fatty acids and an approximately twofold reduction in C18:1. Remarkably, however, the level of the most abundant unsaturated fatty acid, C16:1, appeared unaffected in the desaturase mutant (Figure 3C). Under these conditions, however, the ratio of unsaturated to saturated fatty acids in the desaturase mutant is approximately twofold lower than in wild-type cells. This ratio starts to significantly decline after a shift to nonpermissive conditions for 2 h (Figure 3D). Taken together these observations indicate that the desaturase mutant is fully viable under conditions where the mutant enzyme is observed to relocalize.

Figure 3.

Growth rate, viability, and fatty acid composition of the desaturase mutant. (A) Comparison of growth rates of the ole1ts mutant (YRS1327) and wild-type (W303) strains at 24°C or after a shift to 37°C. Cells were cultivated at the temperature indicated, and cell density was determined by measuring OD600 nm. (B) Relative viability of the desaturase mutant after a shift to nonpermissive conditions. ole1ts (YRS1327) and wild-type (W303) cells were cultivated at 24°C and shifted to 37°C for the time indicated. Cell viability was determined by counting the number of colony forming units. (C) Comparison of fatty acid composition of desaturase mutant and wild-type cells. ole1ts mutant (YRS1327) and wild-type (W303) strains were cultivated at 24°C, and fatty acid composition was determined by GC analysis. (D) Comparison of unsaturated to saturated fatty acid ratio of desaturase mutant and wild-type cells. ole1ts (YRS1327) and wild-type (W303) cells were cultivated at 24°C, shifted to 37°C for the time indicated, the fatty acid composition was determined by GC analysis, and the ratio of unsaturated to saturated fatty acids was calculated.

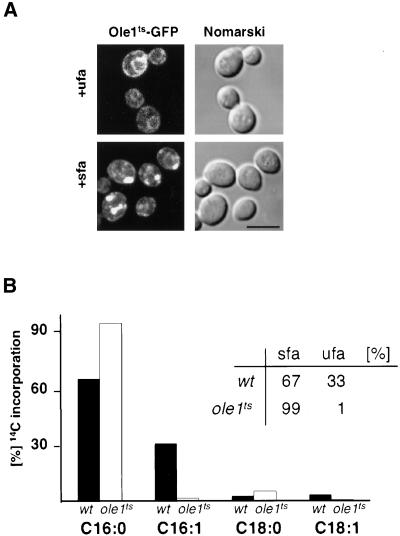

Relocalization of the Mutant Enzyme is Lipid Dependent

To determine whether relocalization of the mutant desaturase is dependent on its enzyme activity, cells were cultivated in the presence of either saturated or unsaturated fatty acids before incubation at nonpermissive conditions. Microscopic examination revealed that relocalization of the mutant desaturase did not occur in cells cultivated with UFAs, but was observed in cells cultivated with SFAs, indicating that the subcellular relocalization is lipid dependent (Figure 4A).

Figure 4.

Relocalization of the mutant desaturase is lipid dependent and results in the synthesis of more saturated lipids. (A) Relocalization of the mutant desaturase in cells cultivated with either saturated (sfa) or unsaturated (ufa) fatty acids. Cells expressing Ole1tsp-GFP (YRS1314) were cultivated in the presence of fatty acids at 30°C for 2 h before a shift to 37°C for 30 min. Bar, 5 μm. (B) Incorporation of [14C]palmitic acid into the phospholipid fraction of ole1ts mutant cells. Cells were pulse-labeled with [14C]palmitic acid at 37°C for 15 min, and incorporation of radiolabeled fatty acids into newly synthesized phospholipids was determined by radio-GC analysis. A comparison of the relative content of saturated (sfa) and unsaturated (ufa) fatty acids in newly synthesized lipids of wild-type and desaturase mutant cells is shown in the table inset.

To determine whether lipid synthesis is affected under these conditions, cells were pulse-labeled with the saturated fatty acid, [14C]palmitic acid, and incorporation of saturated and unsaturated radiolabeled fatty acids into phospholipids was monitored. After a shift to nonpermissive conditions for 30 min, the conversion of palmitic to palmitoleic acid in ole1ts mutant cells was reduced to 1% of wild-type levels. This is compensated for by an increased incorporation of palmitic acid into newly synthesized phospholipids in the mutant compared with wild type (Figure 4B). Similarly, incorporation of saturated C18 was greatly increased at the expense of the unsaturated C18:1. These results indicate that a temperature-induced block in desaturase activity does not affect the rate of incorporation of fatty acids into phospholipids but results in the incorporation of more saturated acyl chains.

Relocalization of the Mutant Desaturase Is Selective and Precedes Alterations in Mitochondrial Structures

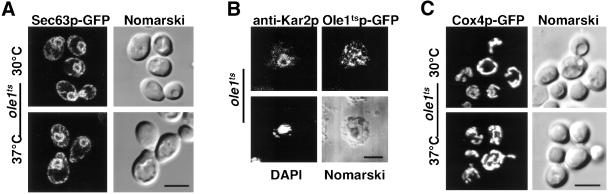

To examine whether localization of other ER resident proteins is affected under conditions where the mutant desaturase displays subcellular relocalization, the distribution of Sec63p, an integral membrane protein and component of the ER translocon (Rothblatt et al., 1989), and that of Kar2p, a soluble lumenal protein of the ER (Normington et al., 1989), were investigated. ER localization of a functional GFP-tagged version of Sec63p was not affected in the desaturase mutant strain under nonpermissive conditions (Figure 5A). To simultaneously detect an ER resident protein and the desaturase, Kar2p was localized by immunofluorescence microscopy in cells expressing the GFP-tagged mutant desaturase. Under permissive conditions, Kar2p colocalized with the mutant desaturase in the ER (unpublished data). However, under nonpermissive conditions, the desaturase displayed its characteristic punctuate relocalization, whereas Kar2p displayed perinuclear ring staining (Figure 5B). These results indicate that the subcellular relocalization is specific for the desaturase and does not affect the distribution of other ER resident proteins.

Figure 5.

Relocalization of the desaturase does not affect ER localization of Sec63p and Kar2p and mitochondrial morphology. (A) Localization of Sec63p-GFP in the desaturase mutant strain. The ole1ts mutant strain harboring a plasmid born SEC63-GFP fusion (YRS1342) was cultivated at 30°C to early logarithmic growth phase and examined by fluorescence microscopy either before (a) or after shifting cells to 37°C for 2 h (c). (B) Simultaneous localization of Kar2p and Ole1tsp-GFP in the desaturase mutant strain. Strain YRS1314 was cultivated at 30°C to early logarithmic growth phase and shifted to 37°C for 30 min before fixation and preparation for immunofluorescence analysis. Kar2p was detected using a polyclonal antibody and a lissamine-rhodamine (LRSC)-conjugated secondary antibody. ER localization of Kar2p (e) is unaffected in cells that display subcellular relocalization of Ole1tsp-GFP (f). Panels e to h show the same cell. (C) Localization of Cox4p-GFP in the desaturase mutant. The ole1ts mutant strain harboring a plasmid born COX4-GFP fusion (YRS1000) was cultivated at 30°C to early logarithmic growth phase and examined by fluorescence microscopy either before (i) or after shifting cells to 37°C for 30 min (k). DAPI staining of DNA (g) and Nomarski view (b, d, h, j, and l) of the corresponding visual fields are indicated. Bar, 5 μm.

Within the 30-min time frame of the observed relocalization of the mutant desaturase, mitochondrial morphology was not affected, as determined by examining the localization of the mitochondrial Cox4p-GFP (Figure 5C). This is consistent with the fact that collapse of the mitochondrial reticulum in ole1ts mutant cells is first observed after a shift to nonpermissive conditions for more than 90 min (Stewart and Yaffe, 1991).

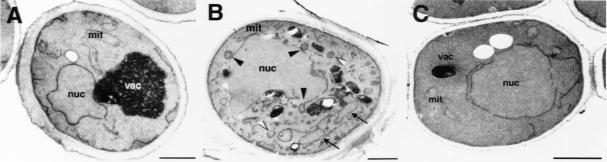

Morphological Analysis of Desaturase Mutant Cells

The desaturase is an integral membrane protein, and the mutant enzyme displays intracellular relocalization; thus, one would predict the presence of aberrant membrane profiles in cells that exhibit relocalization of the desaturase. To test this prediction, wild-type and desaturase mutant cells were shifted to nonpermissive conditions for 15 min, fixed, and processed for ultrastructural analysis by EM. The desaturase mutant exhibited aberrant membrane profiles that were not observed in wild-type cells. Large membrane delineated structures (∼180-nm diameter) were observed in association with the nuclear membrane (black arrowheads in Figure 6B). Membrane enclosed structures of similar size were also present in the cytosol (white arrowheads in Figure 6B), and a membrane delineated compartment that could not be assigned to any subcellular organelle was observed at the cell periphery (arrows in Figure 6B). These membrane alterations were observed in ∼80% of mutant cell sections analyzed. No comparable membrane profiles were apparent in the desaturase mutant strain under permissive conditions (Figure 6C) or under nonpermissive conditions when cultivated in the presence of UFAs (unpublished data), indicating that the formation of these aberrant membrane structures was lipid dependent.

Figure 6.

Morphological analysis of desaturase mutant cells by EM. Wild-type (W303, A) and ole1ts mutant cells (YRS1327, B and C) were grown at 30°C to the early logarithmic phase and shifted to 37°C for 15 min (A and B) or left at 30°C (C). Cells were fixed and prepared for ultrastructural analysis by electron microscopy. Aberrant membranous structures in close proximity to the nuclear membrane (black arrowheads) and in the cytosol of ole1ts mutant cells are indicated (white arrowheads). A large membrane enclosed compartment at the cell periphery is indicated by black arrows. Nuc, nucleus; vac, vacuole; mit, mitochondria. Bar, 1 μm.

To determine the subcellular localization of the mutant desaturase at the ultrastructural level, the mutant protein was tagged at the C terminus with protein A (PrA). This tagged version of the mutant desaturase was functional and displayed subcellular relocalization upon a shift to nonpermissive conditions as assessed by immunofluorescence microscopy (unpublished data). Immunolocalization of this version of the desaturase using an anti-PrA primary antibody followed by a colloidal gold–labeled secondary antibody revealed specific staining of an unusual electron transparent large compartment at the cell periphery in cells shifted for 30 min to nonpermissive conditions (Figure 7A). On the basis of the fact that this compartment was only observed in mutant cells, we reasoned that it might correspond to the large peripheral compartment shown in Figure 6B. The different morphological appearance of this compartment in the two cells could be due to differences in the fixation procedure between cells prepared for morphological analysis and those prepared for immunolocalization (see MATERIALS AND METHODS). To test this possibility, cells were fixed using a third, cryo-fixation protocol. Examination of cryo-fixed desaturase mutant cells again revealed the presence of a large peripheral compartment in ∼30% of cell sections analyzed. Under these conditions, however, the compartment appeared to contain distinct units of electron-dense material within an otherwise electron-transparent background (Figure 7B). On the basis of the fact that this compartment is again only observed in the desaturase mutant and not in wild-type cells, we suggest that it represents the desaturase-containing peripheral compartment that stains positive with the anti-PrA antibody. The morphological appearance of this compartment thus appears to be strongly affected by the precise fixation conditions used.

Figure 7.

Morphological analysis of the desaturase enriched peripheral compartment. Cells expressing a protein A–tagged mutant desaturase (YRS1569) were grown at 30°C to the early logarithmic phase and shifted to 37°C for 30 min. Cells were prepared for immunogold localization of the desaturase (A) and for morphological analysis after cryo-fixation (B). An aberrant peripheral compartment that stains with the gold-labeled secondary antibody (A) or contains electron-dense material (B) is indicated by arrowheads. Nuc, nucleus. Bar, 1 μm.

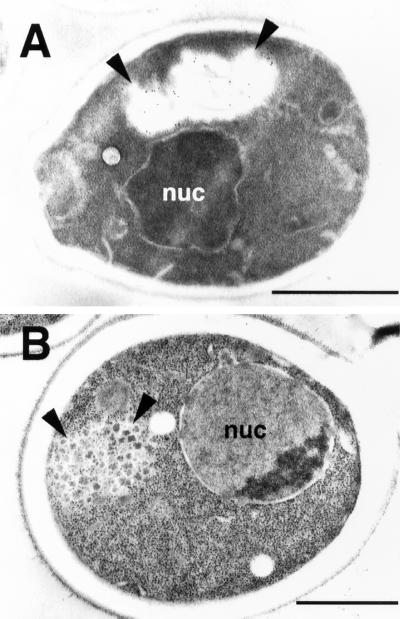

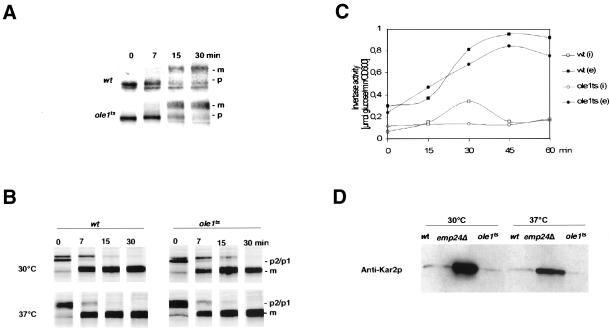

Relocalization of the Mutant Desaturase Does Not Affect the Secretory Pathway

Given the dramatic ultrastructural alterations of cellular membranes in the desaturase mutant cells, we examined whether protein maturation and secretion were conditionally affected in these cells. Therefore, maturation of the glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchored membrane protein Gas1p was analyzed. Gas1p exits the ER as a 105-kDa GPI-anchored precursor and matures in the Golgi apparatus to a 125-kDa form (Fankhauser and Conzelmann, 1991). The accumulation of the ER form of Gas1p is a sensitive assay to detect perturbations in ER-to-Golgi transport. However, in contrast to lcb1-100, a ts mutant in ceramide biosynthesis that is known to delay maturation of Gas1p (Sütterlin et al., 1997), Gas1p maturation was not affected in the desaturase mutant when analyzed by Western blot (unpublished data). Similarly the kinetics of Gas1p maturation in the desaturase mutant at nonpermissive conditions was comparable to that of wild-type cells when examined by pulse-chase analysis and immunoprecipitation (Figure 8A).

Figure 8.

Analysis of the secretory pathway in the desaturase mutant strain. (A) Maturation of Gas1p was analyzed in wild-type (W303), and ole1ts (YRS1327) by pulse-chase analysis and immunoprecipitation. Cells were preshifted to 37°C for 15 min before labeling with [35S]methionine for 5 min and chasing for the time points indicated. Gas1p was recovered by immunoprecipitation, subjected to SDS-PAGE, and visualized by autoradiography. The position of the precursor 105-kDa (p, ER) and mature 125-kDa (m, Golgi) form of Gas1p is indicated to the right. (B) Maturation of CPY. Wild-type (W303) and ole1ts (YRS1327) mutant cells were incubated at 30°C or preshifted to 37°C for 15 min before labeling with [35S]methionine for 5 min and chasing for the time points indicated. CPY was recovered by immunoprecipitation, subjected to SDS-PAGE, and visualized by autoradiography. The positions of precursors (p1, ER; p2, Golgi) and that of the mature form of CPY (m/vacuolar) are indicated. (C) Secretion of invertase was analyzed in wild-type (W303) and ole1ts (YRS1327) mutant cells. After invertase induction by low glucose, cells were preshifted to 37°C for 15 min. Samples were removed at the time points indicated and the activity of internal (i) and secreted (e) invertase was determined. (D) Secretion of Kar2p was analyzed in wild-type (wt, W303), emp24Δ (RH1961), and ole1ts (YRS1327) mutant cells. Exponentially growing cells were washed, resuspended in fresh media, and incubated at either 30 or 37°C for 1 h. Proteins secreted into the media were analyzed by Western blot with an anti-Kar2p antibody.

To examine whether the kinetics of ER-to-Golgi transport of soluble proteins is affected, CPY maturation in the desaturase mutant was examined by pulse-chase analysis. CPY leaves the ER as a 67-kDa preprotein to mature in the Golgi apparatus to a 69-kDa form, which is cleaved to the active 61-kDa protease in the vacuole. After a preshift to 37°C for 15 min, the desaturase mutant exhibited wild-type kinetics of CPY maturation, indicating that vesicular transport between ER and the vacuole is not impaired under conditions where the mutant desaturase displays intracellular relocalization (Figure 8B). Vesicular transport between the ER and the plasma membrane was also not affected in the mutant, as indicated by the wild-type kinetics of invertase induction and secretion (Novick and Schekman, 1979; Figure 8C).

To complete the analysis of the secretory pathway, we examined whether selection of protein cargo destined for vesicular transport out of the ER is impaired in the desaturase mutant. Therefore, secretion of Kar2p into the growth medium was analyzed. In contrast to an emp24Δ mutant strain that lacks one of eight members of the yeast p24 family of cargo receptors (Schimmöller et al., 1995; Elrod-Erickson and Kaiser, 1996), the desaturase mutant strain did not secrete significant amounts of Kar2p under permissive or nonpermissive conditions (Figure 8D). Taken together, these results indicate that the fidelity and efficiency of the secretory pathway is not perturbed under conditions that result in the subcellular relocalization of the desaturase.

Relocalization of the Mutant Desaturase Is Not Allele Specific

While this analysis was in progress, we learned of the existence of a second ts allele of OLE1, isolated in a screen for mitochondrial inheritance mutants similar to the one that yielded the original ole1ts allele (Hermann et al., 1997). Sequence analysis of this second, ole1ts-2, allele revealed a serine to phenylalanine mutation at amino acid position 303 (S303F), carboxy-terminal to the fourth transmembrane domain. In contrast to the first allele (A484V), the S303F mutation affects a residue that is conserved between desaturases from rat, mouse, hamster, and pig (Meesters et al., 1997). Examination of the subcellular distribution of a GFP-tagged version of this allele again revealed ER localization under permissive conditions and the characteristic relocalization upon a short incubation at nonpermissive conditions (unpublished data). Morphological analysis of these cells by EM revealed aberrant membrane structures at the nuclear membrane and an unusual peripheral compartment, similar to what we have observed with the original allele (unpublished data). These observations indicate that relocalization of the mutant desaturase is not allele specific, but that it may be a more general phenotype of cells that experience an acute shortage of UFAs.

Biochemical Characterization of the Relocalization

To determine whether relocalization of the desaturase affects the biochemical properties of the enzyme, cells expressing the GFP-tagged mutant desaturase were incubated at permissive or nonpermissive conditions, and the fractionation properties of the desaturase were examined by differential centrifugation. This analysis revealed no significant difference in the fractionation properties of the ER-localized compared with the relocated form of the desaturase (unpublished data).

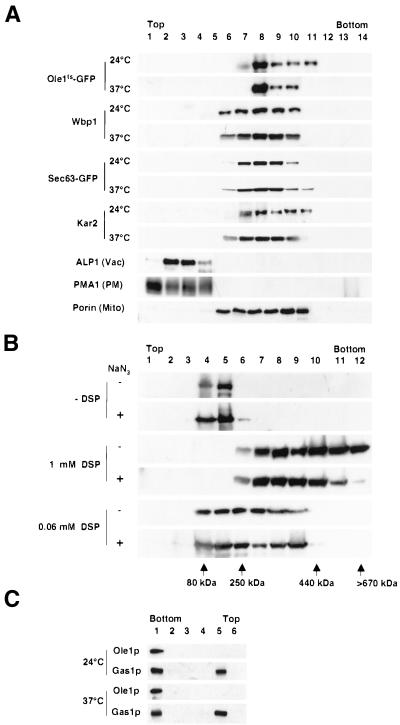

We then determined whether the ER-localized desaturase could be distinguished from the relocalized form by equilibrium density gradient centrifugation. Therefore, cells expressing the GFP-tagged mutant desaturase were incubated at permissive or nonpermissive conditions, and membrane association of the desaturase was compared after separation on an Accudenz gradient. This analysis revealed cofractionation of Ole1tsp-GFP with the ER resident proteins Wbp1p, Kar2p, and Sec63p-GFP, independent of whether cells were incubated at permissive or nonpermissive condition, indicating that relocalization of the desaturase does not affect the density of its membranous compartment (Figure 9A).

Figure 9.

Biochemical characterization of the relocalization. (A) Cells expressing the mutant desaturase fused to GFP (YRS1314) and desaturase mutant cells expressing a Sec63p-GFP fusion protein (YRS1342) were cultivated to early logarithmic phase and incubated at either 24 or 37°C for 30 min. Cells were homogenized and membranes were fractionated on an Accudenz gradient. Distribution of the GFP-tagged desaturase and that of the ER markers Wbp1p, and Kar2p, and marker proteins for the vacuole (Vac), ALP1, the plasma membrane (PM), PMA1, and mitochondria (Mito), porin, were determined by Western blot analysis of gradient fractions prepared from YRS1314. The distribution of Sec63p-GFP was examined in gradient fractions prepared from YRS1342. (B) Cells expressing the mutant desaturase fused to GFP (YRS1314) were cultivated to early logarithmic phase and incubated with or without NaN3 for 15 min at 24°C. Cells were homogenized, and proteins were cross-linked by incubation with or without DSP. Proteins were solubilized and fractionated on a 5–40% sucrose gradient. The cross-linker was cleaved under reducing conditions and the GFP-tagged desaturase was detected by Western blots. The position of the desaturase relative to molecular-weight standards fractionated in parallel is shown. (C) Cells expressing the mutant desaturase fused to GFP (YRS1314) were cultivated to early logarithmic phase and incubated at 24 or 37°C for 30 min. Cells were homogenized and membranes were solubilized by incubation in 1% Triton X-100. Detergent-resistant membranes were fractionated by floatation in an Optiprep gradient. Gradient fractions were analyzed for the presence of Gas1p and the desaturase by Western blots.

To determine whether relocalization of the desaturase involves protein–protein aggregation, cells expressing the GFP-tagged mutant desaturase were incubated with or without sodium azide, which induces relocalization of the desaturase (see below), and proteins were cross-linked with different concentrations of the membrane permeable cleavable cross-linker dithiobis(succinimidylpropionate) (DSP). Proteins were then solubilized by detergents and separated on a sucrose gradient. This analysis allowed for a quantitative cross-linking of the desaturase into higher molecular weight aggregates, depending on the concentration of DSP used. This approach, however, failed to reveal a significant difference between the ER localized and the relocalized form of the desaturase (Figure 9B)

Ordered acyl chain packaging is a driving force for the generation of detergent-resistant membrane domains (Schroeder et al., 1994; Brown and London, 2000). In yeast, the GPI-anchored cell surface protein Gas1p and the plasma membrane ATPase, Pma1p, are greatly enriched in the detergent-insoluble membrane fraction (Bagnat et al., 2000). We thus tested whether relocalization of the desaturase affects the detergent solubility of the enzyme. Therefore, membranes from mutant cells incubated at permissive or nonpermissive conditions were extracted with the nonionic detergent Triton X-100, and detergent insoluble membranes were floatated in an Optiprep gradient. This analysis revealed that the desaturase fractionates in the detergent soluble portion of the gradient independent of whether cells were incubated at permissive or nonpermissive conditions (Figure 9C).

Taken together this biochemical analysis of the relocalization revealed no specific difference between the ER-localized and the relocated form of the desaturase.

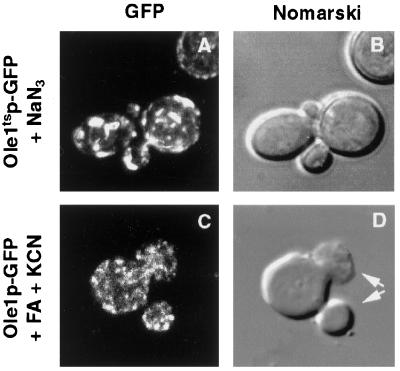

Inhibition of the Wild-type Desaturase Induces Subcellular Relocalization

To test whether a block of desaturase activity is sufficient to induce relocalization of a wild-type enzyme, cells expressing the GFP-tagged enzyme were treated with various desaturase inhibitors and were then analyzed by fluorescence microscopy. Previous studies have shown that the non-heme iron–containing desaturase is inhibited by the iron chelator cyanide or by azide (Oshino et al., 1966). We thus examined whether treatment of cells expressing the GFP-tagged mutant version of the desaturase with cyanide or azide would induce relocalization of the enzyme. Remarkably, the mutant desaturase displayed relocalization already at permissive conditions when cells were incubated with 10 mM sodium azide for 30 min, indicating that a temperature-shift per se is not required for relocalization (Figure 10A). Cyanide treatment of cells expressing the GFP-tagged, wild-type desaturase also induced relocalization of the enzyme. In this case, relocalization was most notable if the cells were precultured in media containing fatty acids that inhibit the desaturase, such as trans-10, cis-12–conjugated linoleic acid (Park et al., 2000; Figure 10C). The addition of inhibitory fatty acids alone did not arrest cell growth or induce relocalization of the mutant enzyme but induced an increased expression of the desaturase as apparent by fluorescence microscopy. The cyanide- and fatty acid–induced relocalization of the wild-type enzyme resulted in a somewhat different more finely grained appearance of the punctuate structures compared with that observed in mutant cells. Cyanide-treated, wild-type cells exhibited multiple, nuclei-containing buds, a phenotype characteristic for ole1ts/mdm2 mutant cells incubated under nonpermissive conditions for longer periods of time (Stewart and Yaffe, 1991; Figure 10D).

Figure 10.

Inhibition of the desaturase induces subcellular relocalization in wild-type cells. Cells expressing the mutant desaturase fused to GFP (YRS1314) were cultivated to early logarithmic phase and incubated with 10 mM sodium azide for 30 min before analysis by fluorescence microscopy (A). Cells expressing the wild-type desaturase fused to GFP (YRS1315) were cultivated in media containing conjugated linoleic acid (100 μM) for 2 h and were then incubated with KCN (100 mM) for 30 min (C). Arrows in D mark a cell with two nuclei containing buds. Nomarski view (B and D) of the corresponding visual fields is shown to the right. Bar, 5 μm.

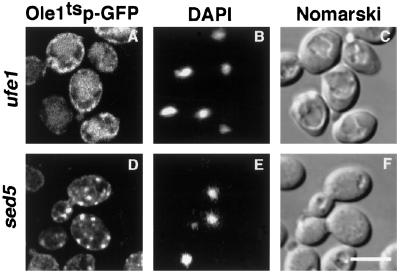

Formation of the Peripheral Desaturase-enriched Compartment Requires UFE1

To examine whether the subcellular relocalization of the desaturase is under physiological control and to define the identity of the peripheral, desaturase-enriched compartment, we examined whether relocalization of the desaturase is energy dependent and whether SNAREs (membrane-soluble N-ethylmaleimide–sensitive factor attachment protein receptors) are required for the formation of the peripheral structures. Therefore, relocalization of the desaturase was analyzed in cells that were depleted of energy by incubation in media containing deoxyglucose and sodium azide plus fluoride. Under these conditions, secretion of invertase is blocked, but the desaturase is still observed to relocalize, indicating that relocalization is not energy dependent (unpublished data). To examine whether formation of the peripheral desaturase-containing structures requires SNARE function, relocalization of the desaturase was analyzed in ts mutants of UFE1 and SED5, two syntaxin homologues required for ER (Lewis and Pelham, 1996; Patel et al., 1998) and Golgi fusion (Hardwick and Pelham, 1992), respectively. This analysis revealed that UFE1 but not SED5 was required for the formation of the peripheral membrane compartment, indicating that the peripheral compartment is an ER derivative (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

Formation of the peripheral membrane domain requires the ER SNARE Ufe1. Cells expressing the GFP-tagged mutant desaturase in a ufe1-1 (YRS1353; A), or sed5–1 (YRS1357; D), mutant background were cultivated to early logarithmic growth phase and incubated at 37°C for 15 min before analysis by fluorescence microscopy. DAPI staining of DNA (B and E) and Nomarski view (C and F) of the corresponding visual fields are shown to the right. Bar, 5 μm.

DISCUSSION

We report that in a conditional desaturase mutant, ole1ts, the desaturase alters its subcellular distribution upon incubation at nonpermissive conditions. This relocalization is selective for the desaturase, because other soluble and membrane-bound ER residents do not change their subcellular distribution. Relocalization of the desaturase is not allele specific and is independent of temperature, because it can be induced in mutant and wild-type cells upon treatment with enzyme inhibitors. These observations indicate that relocalization of the desaturase does not require a temperature-induced conformational change of the enzyme, a proposition that is supported by the fact that relocalization of the desaturase is independent of the formation of protein aggregates and does not affect the biochemical properties of the enzyme. These observations are compatible with the suggestion that relocalization of the desaturase occurs in response to a lack of desaturase function, which is coupled to an alteration in membrane lipid composition.

The fact that relocalization of the desaturase is energy independent and not blocked in various conditional coat protein (COPI, COPII) mutants (unpublished data) indicates that relocalization of the desaturase is nonvesicular. The observation that relocalization is dependent on the ER SNARE Ufe1p but does not affect the fractionation properties of the desaturase suggests that the relocalized form of the desaturase remains in an ER-like compartment, which has segregated away from the biosynthetic active part of the ER.

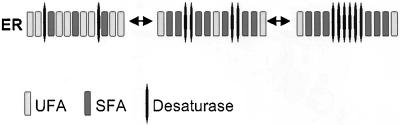

The desaturase is a lipid-modifying integral membrane protein whose activity affects membrane fluidity. Because the subcellular relocalization of the enzyme is lipid dependent, we propose that a deficiency in desaturase function results in a local alteration of the membrane fluidity. Pulse-labeling experiments with palmitic acid revealed that glycerophospholipid synthesis is continuing in the desaturase mutant under nonpermissive conditions. At the same time, however, the synthesis of UFAs was greatly diminished, resulting in the incorporation of predominantly SFAs into newly synthesized glycerophospholipids, which are normally highly unsaturated (Schneiter et al., 1999). Lateral aggregation of such saturated lipids would result in the formation of more ordered desaturase-enriched membrane domains in the plane of the ER membrane (Figure 12). The formation of such domains before relocalization of the desaturase to the cell periphery is consistent with the morphological transformations observed by fluorescence microscopy in the ts mutant upon short incubations at nonpermissive conditions (e.g., Figure 2D). The lipid dependence of the relocalization event is underscored by the fact that relocalization of the desaturase does not occur in cells that lack the capacity for the de novo synthesis of the aminoglycerophospholipids as is the case in phosphatidylserine synthase mutants (cho1Δ mutant; V. Tatzer and R. Schneiter, unpublished observation).

Figure 12.

Model for the relocalization of the desaturase. Inactivation of the desaturase results in the local accumulation of lipids with more saturated acyl chains (SFA) at the expense of lipids with unsaturated acyl chanis (UFA). Subsequent lateral aggregation of these SFA-enriched lipid domains induces relocalization of the desaturase.

While acyl chain desaturation is liquefying the membrane, a high degree of acyl chain saturation has been implicated in the formation of membrane domains/rafts, which function in protein sorting and signal transduction (Simons and Ikonen, 1997; Brown and London, 2000). These domains appear to be formed through strong hydrophobic interactions between sterols and lipids with saturated acyl chains (Schroeder et al., 1994). They are particularly rich in sphingolipids and cholesterol and resist solubilization by nonionic detergents (Brown and Rose, 1992). Our analysis of the detergent extractability of the desaturase revealed that the enzyme fractionates with the detergent-soluble part of the membrane, irrespective of whether the cells were incubated at permissive or nonpermissive conditions. The hydrophobic interactions that are expected to drive formation of the saturated glycerophospholipid domains in the desaturase mutant are not likely to be enriched in sterols and sphingolipids, and hence are probably too weak to resist solubilization by detergents. Using other detergents such as Brij 58, CHAPS, and Nonidet P40 did also not reveal any difference between the ER-localized and relocated form of the enzyme.

Under conditions where the desaturase is inactive and relocalizes to the cell periphery, the kinetic and fidelity of the secretory transport is unaffected. This is surprising, given the fact that in vitro budding of vesicles from chemically defined liposomes is sensitive to the degree of lipid desaturation (Matsuoka et al., 1998). This observation suggests that vesicle formation in vivo might be less sensitive to the acyl chain composition of the lipids or that the lipid pool of the secretory pathway is not immediately affected by a lack of desaturase function. This second possibility is supported by the observation that upon inositol starvation of an auxotrophic mutant (ino1), the defect in Gas1p maturation substantially precedes the onset of any defect in CPY processing (Doering and Schekman, 1996).

The two conditional desaturase alleles characterized in this study have been isolated in screens for mutants that affect mitochondrial morphology and inheritance (Stewart and Yaffe, 1991; Hermann et al., 1997). Our observation that the localization of the desaturase and hence part of the ER is affected in these mutants, together with the fact that mutants that affect the structure of the cortical ER also affect mitochondrial morphology (Prinz et al., 2000), suggests that the mitochondrial phenotype exhibited by the desaturase mutants may be a consequence of the altered ER structure in these cells.

It is interesting to note that a number of conditional mutants in fatty acid metabolism affect the structure of the ER. For example, a ts mutant in the rate-limiting enzyme of fatty acid synthesis, acetyl-CoA carboxylase, displays a striking separation of inner and outer nuclear membranes (Schneiter et al., 1996). A very similar phenotype is observed in a conditional mutant of the two membrane-bound transcription factors, mga2Δ spt23ts. In these cells, however, the phenotype is rescued by supplementation with UFA (Zhang et al., 1999). In ole1Δ mutant cells that have been depleted of UFA, on the other hand, cellular morphology is disturbed to an extent that makes a phenotypic characterization difficult (Zhang et al., 1999). ole1ts (mdm2) mutants after prolonged incubation at nonpermissive conditions (5.5 h), on the other hand, display collapsed mitochondria and aberrant cytosolic membrane profiles (McConnell et al., 1990).

Taken together, the subcellular relocalization of the acyl chain desaturase from an evenly distributed ER localization to a more punctuate localization at the cell periphery upon inactivation of the enzyme appears to reflect a novel, selective, lipid-mediated protein segregation process that possibly takes place in response to a local alteration of the membrane composition and as such provides independent evidence to support the general idea that the membrane lipid composition can affect protein sorting.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank M. Aebi, G. Daum, H. Pelham, P. Philippsen, H. Riezman, M. Rose, R. Schekman, E. Schiebel, J. Shaw, P. Silver, and M. Yaffe for providing strains, plasmids, or antibodies; M. Baird, J. Bremer, and P. Buist for desaturase inhibitors; and G. Daum for comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by the Austrian Science Found (P11731 and F706 to S.D.K., and P13767 and P15210 to R.S.). R.S. acknowledges receipt of a professorial award from the Swiss National Science Foundation.

Abbreviations used:

- CPY

carboxypeptidase Y

- DSP

dithiobis(succinimidylpropionate)

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- PrA

protein A

- SFA

saturated fatty acids

- SNARES

membrane soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor attachment protein receptors

- ts

temperature-sensitive

- UFA

unsaturated fatty acids

Footnotes

DOI: 10.1091/mbc.E02–04–0196.

REFERENCES

- Bagnat M, Keranen S, Shevchenko A, Simons K. Lipid rafts function in biosynthetic delivery of proteins to the cell surface in yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:3254–3259. doi: 10.1073/pnas.060034697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bossie MA, Martin CE. Nutritional regulation of yeast delta-9 fatty acid desaturase activity. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:6409–6413. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.12.6409-6413.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown DA, London E. Structure and function of sphingolipid- and cholesterol-rich membrane rafts. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:17221–17224. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R000005200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown DA, Rose JK. Sorting of GPI-anchored proteins to glycolipid-enriched membrane subdomains during transport to the apical cell surface. Cell. 1992;68:533–544. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90189-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown MS, Goldstein JL. A proteolytic pathway that controls the cholesterol content of membranes, cells, and blood. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:11041–11048. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.20.11041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi JY, Stukey J, Hwang SY, Martin CE. Regulatory elements that control transcription activation and unsaturated fatty acid-mediated repression of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae OLE1 gene. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:3581–3589. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.7.3581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowles CR, Odorizzi G, Payne GS, Emr SD. The AP-3 adaptor complex is essential for cargo-selective transport to the yeast vacuole. Cell. 1997;91:109–118. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)80013-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullis PR, Fenske DB, Hope MJ. Physical properties and functional roles of lipids in membranes. New Compr Biochem. 1996;31:1–33. [Google Scholar]

- Doering TL, Schekman R. GPI anchor attachment is required for Gas1p transport from the endoplasmic reticulum in COPII vesicles. EMBO J. 1996;15:182–191. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyer JM, Mullen RT. Immunocytological localization of two plant fatty acid desaturases in the endoplasmic reticulum. FEBS Lett. 2001;494:44–47. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02315-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elrod-Erickson MJ, Kaiser CA. Genes that control the fidelity of endoplasmic reticulum to Golgi transport identified as suppressors of vesicle budding mutations. Mol Biol Cell. 1996;7:1043–1058. doi: 10.1091/mbc.7.7.1043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fankhauser C, Conzelmann A. Purification, biosynthesis and cellular localization of a major 125-kDa glycophosphatidylinositol-anchored membrane glycoprotein of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Eur J Biochem. 1991;195:439–448. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1991.tb15723.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardwick KG, Pelham HR. SED5 encodes a 39-kD integral membrane protein required for vesicular transport between the ER and the Golgi complex. J Cell Biol. 1992;119:513–521. doi: 10.1083/jcb.119.3.513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein A, Lampen JO. Beta-D-fructofuranoside fructohydrolase from yeast. Methods Enzymol. 1975;42:504–511. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(75)42159-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez CI, Martin CE. Fatty acid-responsive control of mRNA stability—unsaturated fatty acid-induced degradation of the Saccharomyces OLE1 transcript. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:25801–25809. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.42.25801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermann GJ, King EJ, Shaw JM. The yeast gene, MDM20, is necessary for mitochondrial inheritance and organization of the actin cytoskeleton. J Cell Biol. 1997;137:141–153. doi: 10.1083/jcb.137.1.141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoppe T, Matuschewski K, Rape M, Schlenker S, Ulrich H, Jentsch S. Activation of a membrane-bound transcription factor by regulated ubiquitin/proteasome-dependent processing. Cell. 2000;102:577–586. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00080-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knop M, Siegers K, Pereira G, Zachariae W, Winsor B, Nasmyth K, Schiebel E. Epitope tagging of yeast genes using a PCR-based strategy: more tags and improved practical routines. Yeast. 1999;15:963–972. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(199907)15:10B<963::AID-YEA399>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MJ, Pelham HR. SNARE-mediated retrograde traffic from the Golgi complex to the endoplasmic reticulum. Cell. 1996;85:205–215. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81097-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Los DA, Murata N. Structure and expression of fatty acid desaturases. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1394:3–15. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2760(98)00091-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowry OH, Rosenbrough NJ, Farr AL, Randall RJ. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951;193:265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuoka K, Orci L, Amherdt M, Bednarek SY, Hamamoto S, Schekman R, Yeung T. COPII-coated vesicle formation reconstituted with purified coat proteins and chemically defined liposomes. Cell. 1998;93:263–275. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81577-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McConnell SJ, Stewart LC, Talin A, Yaffe MP. Temperature-sensitive mutants defective in mitochondrial inheritance. J Cell Biol. 1990;111:967–976. doi: 10.1083/jcb.111.3.967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonough VM, Stukey JE, Martin CE. Specificity of unsaturated fatty acid-regulated expression of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae OLE1 gene. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:5931–5936. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meesters PAEP, Springer J, Eggink G. Cloning and expression of the Delta(9) fatty acid desaturase gene from Cryptococcus curvatus ATCC 20509 containing histidine boxes and a cytochrome b(5) domain. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1997;47:663–667. doi: 10.1007/s002530050992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell AG, Martin CE. A novel cytochrome b(5)-like domain is linked to the carboxyl terminus of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae delta-9 fatty acid desaturase. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:29766–29772. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.50.29766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munn AL, Heese-Peck A, Stevenson BJ, Pichler H, Riezman H. Specific sterols required for the internalization step of endocytosis in yeast. Mol Biol Cell. 1999;10:3943–3957. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.11.3943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Normington K, Kohno K, Kozutsumi Y, Gething M-J, Sambrook J. S. cerevisiae encodes an essential protein homologous in sequence and function to mammalian BiP. Cell. 1989;57:1223–1236. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90059-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novick P, Schekman R. Secretion and cell-surface growth are blocked in a temperature-sensitive mutant of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76:1858–1862. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.4.1858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oshino N, Imai Y, Sato R. Electron-transfer mechanism associated with fatty acid desaturation catalyzed by liver microsomes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1966;128:13–27. doi: 10.1016/0926-6593(66)90137-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park Y, Storkson JM, Ntambi JM, Cook ME, Sih CJ, Pariza MW. Inhibition of hepatic stearoyl-CoA desaturase activity by trans-10, cis-12 conjugated linoleic acid and its derivatives. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1486:285–292. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(00)00074-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel SK, Indig FE, Olivieri N, Levine ND, Latterich M. Organelle membrane fusion: a novel function for the syntaxin homolog Ufe1p in ER membrane fusion. Cell. 1998;92:611–620. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81129-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preuss D, Mulholland J, Kaiser CA, Orlean P, Albright C, Rose MD, Robbins PW, Botstein D. Structure of the yeast endoplasmic reticulum: localization of ER proteins using immunofluorescence and immunoelectron microscopy. Yeast. 1991;7:891–911. doi: 10.1002/yea.320070902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prinz WA, Grzyb L, Veenhuis M, Kahana JA, Silver PA, Rapoport TA. Mutants affecting the structure of the cortical endoplasmic reticulum in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Cell Biol. 2000;150:461–474. doi: 10.1083/jcb.150.3.461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rape M, Hoppe T, Gorr I, Kalocay M, Richly H, Jentsch S. Mobilization of processed, membrane-tethered SPT23 transcription factor by CDC48(UFD1/NPL4), a ubiquitin-selective chaperone. Cell. 2001;107:667–677. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00595-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnick MA, Mortimer RK. Unsaturated fatty acid mutants of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Bacteriol. 1966;92:597–600. doi: 10.1128/jb.92.3.597-600.1966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothblatt JA, Deshaies RJ, Sanders SL, Daum G, Schekman R. Multiple genes are required for proper insertion of secretory proteins into the endoplasmic reticulum in yeast. J Cell Biol. 1989;109:2641–2652. doi: 10.1083/jcb.109.6.2641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schimmöller F, Singer-Krüger B, Schröder S, Krüger U, Barlowe C, Riezman H. The absence of Emp24p, a component of ER-derived COPII-coated vesicles, causes a defect in transport of selected proteins to the Golgi. EMBO J. 1995;14:1329–1329. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07119.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneiter R, Hitomi M, Ivessa AS, Fasch EV, Kohlwein SD, Tartakoff AM. A yeast acetyl coenzyme a carboxylase mutant links very-long-chain fatty acid synthesis to the structure and function of the nuclear membrane-pore complex. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:7161–7172. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.12.7161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneiter R, et al. Electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry (ESI-MS/MS) analysis of the lipid molecular species composition of yeast subcellular membranes reveals acyl chain-based sorting/remodeling of distinct molecular species en route to the plasma membrane. J Cell Biol. 1999;146:741–754. doi: 10.1083/jcb.146.4.741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneiter R, Kohlwein SD. Organelle structure, function, and inheritance in yeast: A role for fatty acid synthesis? Cell. 1997;88:431–434. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81882-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder R, London E, Brown D. Interactions between saturated acyl chains confer detergent resistance on lipids and glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchored proteins: GPI-anchored proteins in liposomes and cells show similar behavior. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:12130–12134. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.25.12130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sikorski RS, Hieter P. A system of shuttle vectors and yeast host strains designed for efficient manipulation of DNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1989;122:19–27. doi: 10.1093/genetics/122.1.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons K, Ikonen E. Functional rafts in cell membranes. Nature. 1997;387:569–572. doi: 10.1038/42408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart LC, Yaffe MP. A role for unsaturated fatty acids in mitochondrial movement and inheritance. J Cell Biol. 1991;115:1249–1257. doi: 10.1083/jcb.115.5.1249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stukey JE, McDonough VM, Martin CE. Isolation and characterization of OLE1, a gene affecting fatty acid desaturation from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:16537–16544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stukey JE, McDonough VM, Martin CE. The OLE1 gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae encodes the delta 9 fatty acid desaturase and can be functionally replaced by the rat stearoyl-CoA desaturase gene. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:20144–20149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sütterlin C, Doering TL, Schimmöller F, Schröder S, Riezman H. Specific requirements for the ER to Golgi transport of GPI-anchored proteins in yeast. J Cell Sci. 1997;110:2703–2714. doi: 10.1242/jcs.110.21.2703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wach A, Brachat A, Alberti-Segui C, Rebischung C, Philippsen P. Heterologous HIS3 marker and GFP reporter modules for PCR-targeting in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 1997;13:1065–1075. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(19970915)13:11<1065::AID-YEA159>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner S, Paltauf F. Generation of glycerophospholipid molecular species in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Fatty acid pattern of phospholipid classes and selective acyl turnover at sn-1 and sn-2 positions. Yeast. 1994;10:1429–1437. doi: 10.1002/yea.320101106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang SR, Skalsky Y, Garfinkel DJ. MGA2 or SPT23 is required for transcription of the delta 9 fatty acid desaturase gene, OLE1, and nuclear membrane integrity in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1999;151:473–483. doi: 10.1093/genetics/151.2.473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]