Abstract

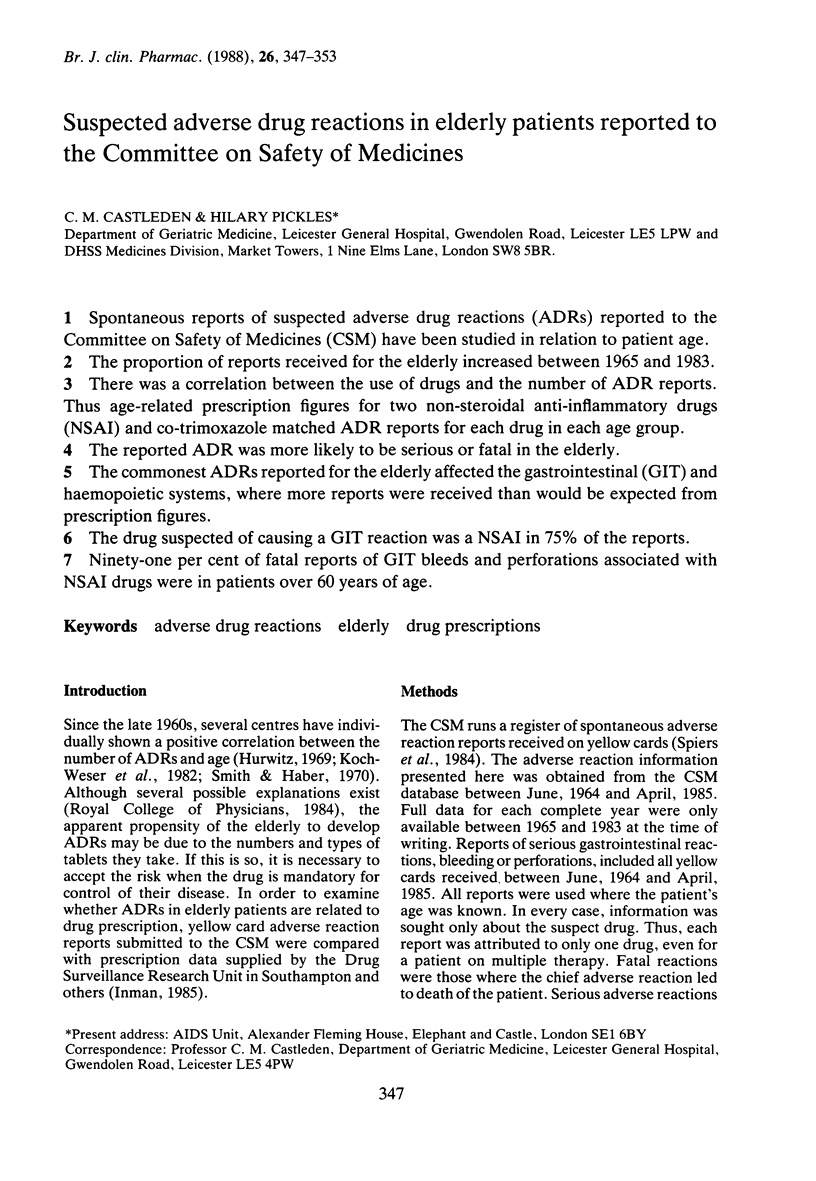

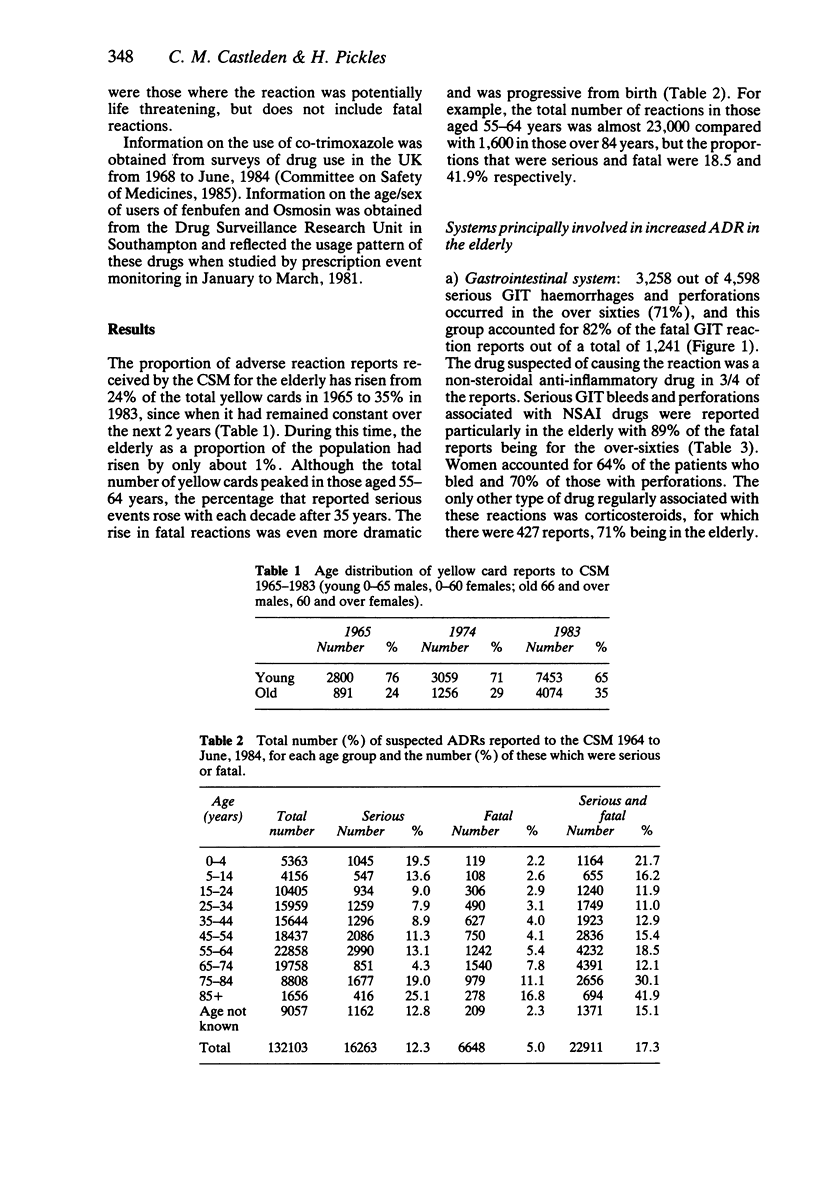

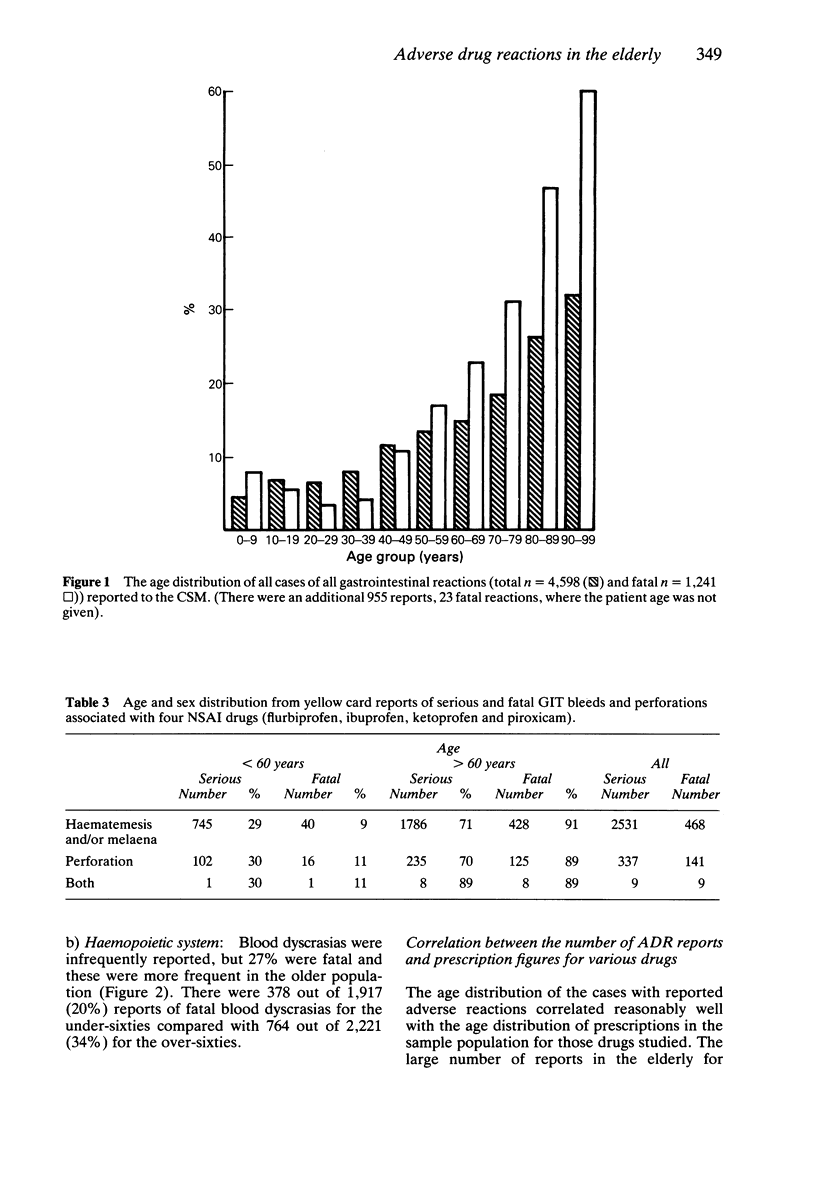

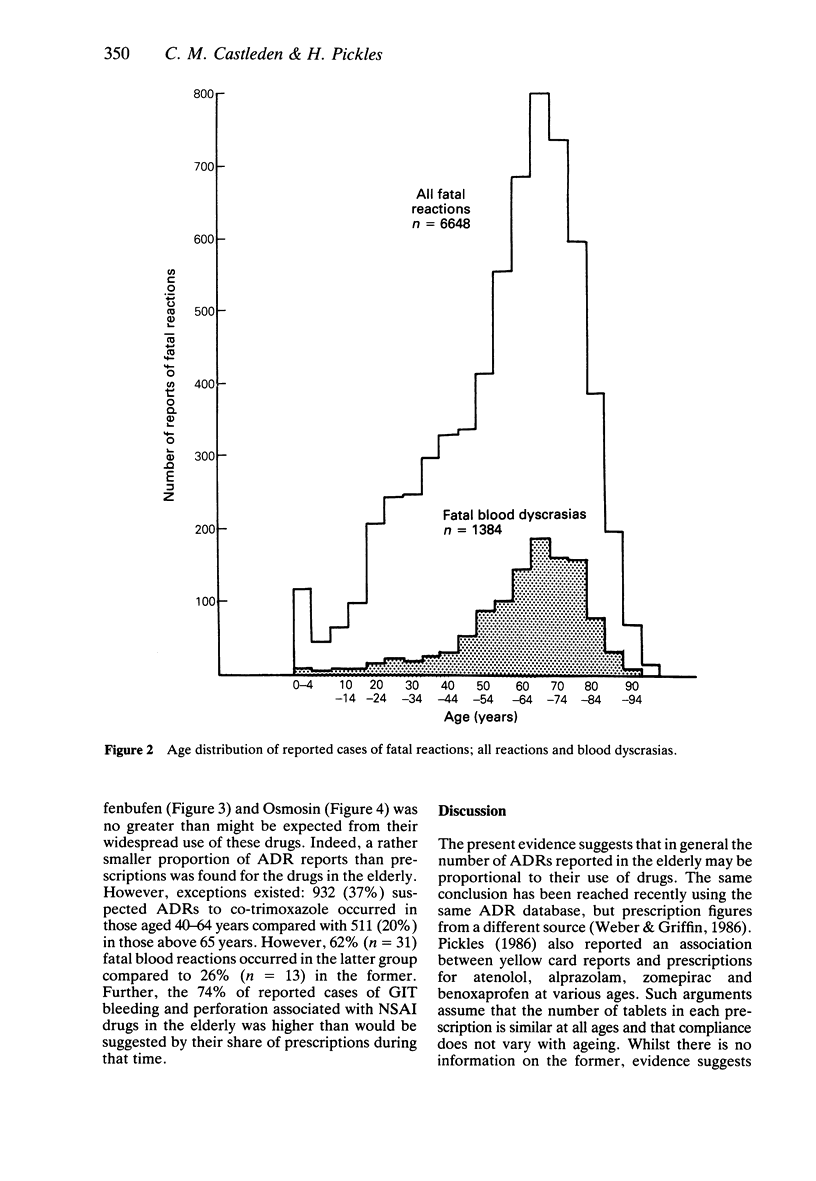

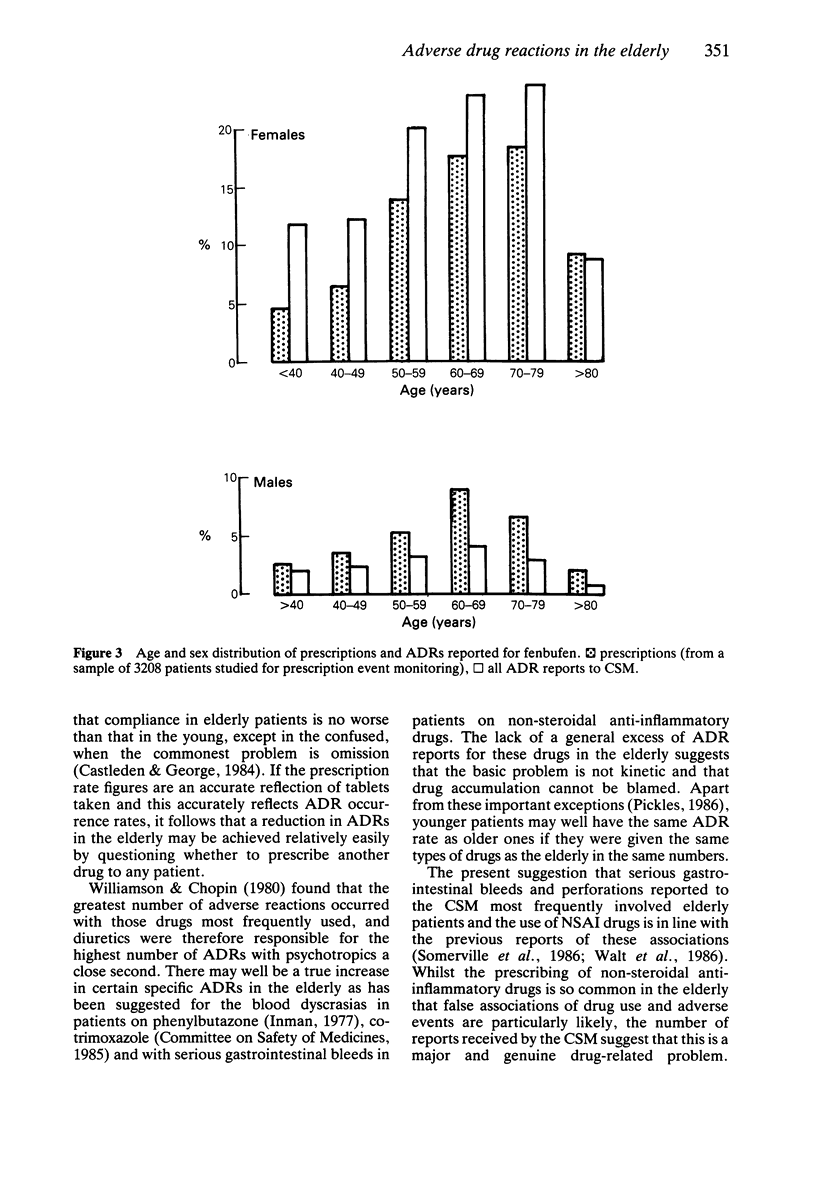

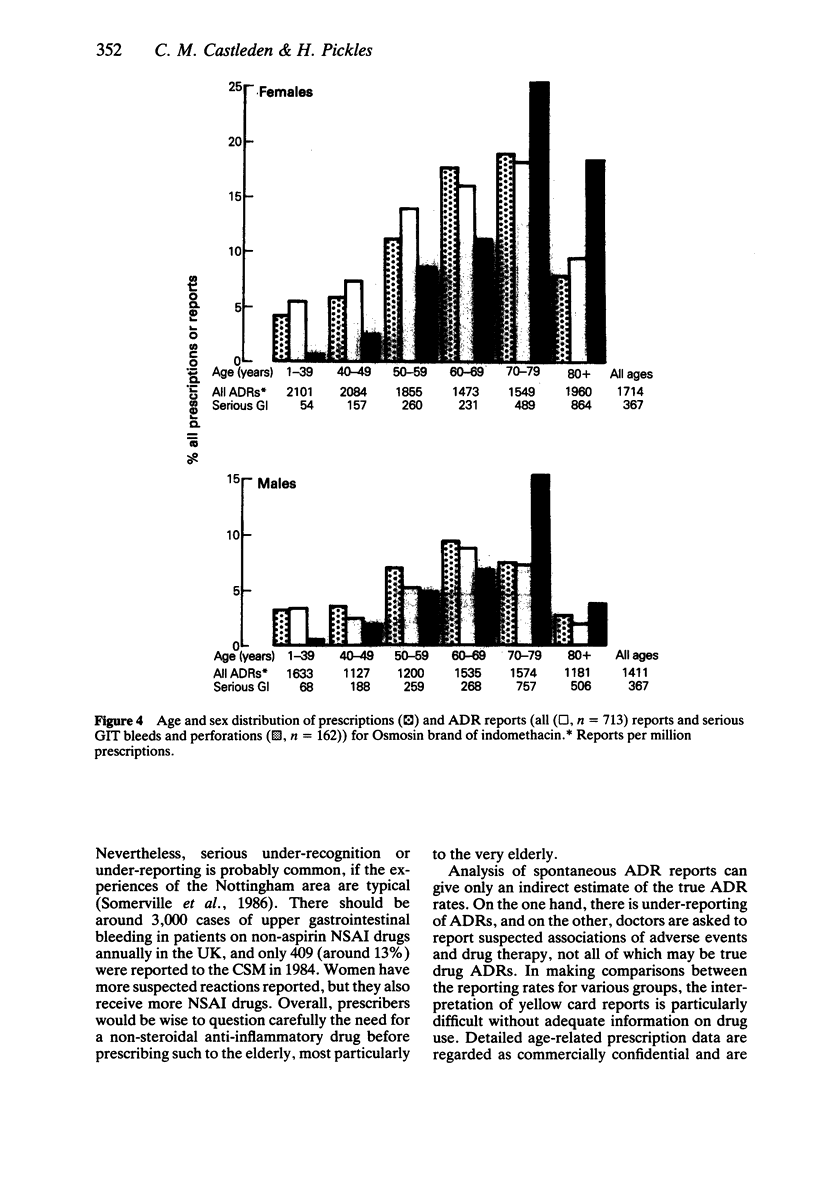

1. Spontaneous reports of suspected adverse drug reactions (ADRs) reported to the Committee on Safety of Medicines (CSM) have been studied in relation to patient age. 2. The proportion of reports received for the elderly increased between 1965 and 1983. 3. There was a correlation between the use of drugs and the number of ADR reports. Thus age-related prescription figures for two non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAI) and co-trimoxazole matched ADR reports for each drug in each age group. 4. The reported ADR was more likely to be serious or fatal in the elderly. 5. The commonest ADRs reported for the elderly affected the gastrointestinal (GIT) and haemopoietic systems, where more reports were received than would be expected from prescription figures. 6. The drug suspected of causing a GIT reaction was a NSAI in 75% of the reports. 7. Ninety-one per cent of fatal reports of GIT bleeds and perforations associated with NSAI drugs were in patients over 60 years of age.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Greenblatt D. J., Sellers E. M., Shader R. I. Drug therapy: drug disposition in old age. N Engl J Med. 1982 May 6;306(18):1081–1088. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198205063061804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurwitz N. Predisposing factors in adverse reactions to drugs. Br Med J. 1969 Mar 1;1(5643):536–539. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.5643.536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inman W. H. Study of fatal bone marrow depression with special reference to phenylbutazone and oxyphenbutazone. Br Med J. 1977 Jun 11;1(6075):1500–1505. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.6075.1500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith T. W., Haber E. Digoxin intoxication: the relationship of clinical presentation to serum digoxin concentration. J Clin Invest. 1970 Dec;49(12):2377–2386. doi: 10.1172/JCI106457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somerville K., Faulkner G., Langman M. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and bleeding peptic ulcer. Lancet. 1986 Mar 1;1(8479):462–464. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(86)92927-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speirs C. J., Griffin J. P., Weber J. C., Glen-Bott M. Demography of the UK adverse reactions register of spontaneous reports. Health Trends. 1984 Aug;16(3):49–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walt R., Katschinski B., Logan R., Ashley J., Langman M. Rising frequency of ulcer perforation in elderly people in the United Kingdom. Lancet. 1986 Mar 1;1(8479):489–492. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(86)92940-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber J. C., Griffin J. P. Prescriptions, adverse reactions, and the elderly. Lancet. 1986 May 24;1(8491):1220–1220. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(86)91208-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson J., Chopin J. M. Adverse reactions to prescribed drugs in the elderly: a multicentre investigation. Age Ageing. 1980 May;9(2):73–80. doi: 10.1093/ageing/9.2.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]