Abstract

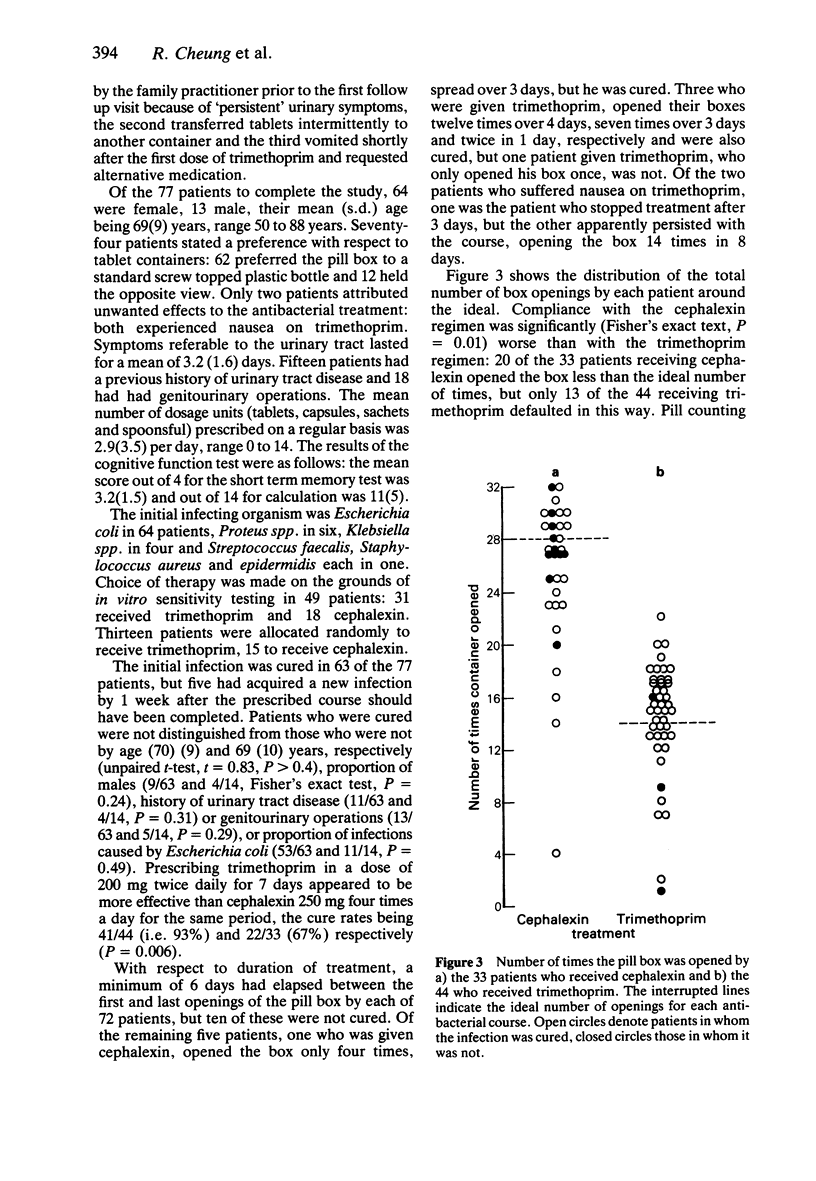

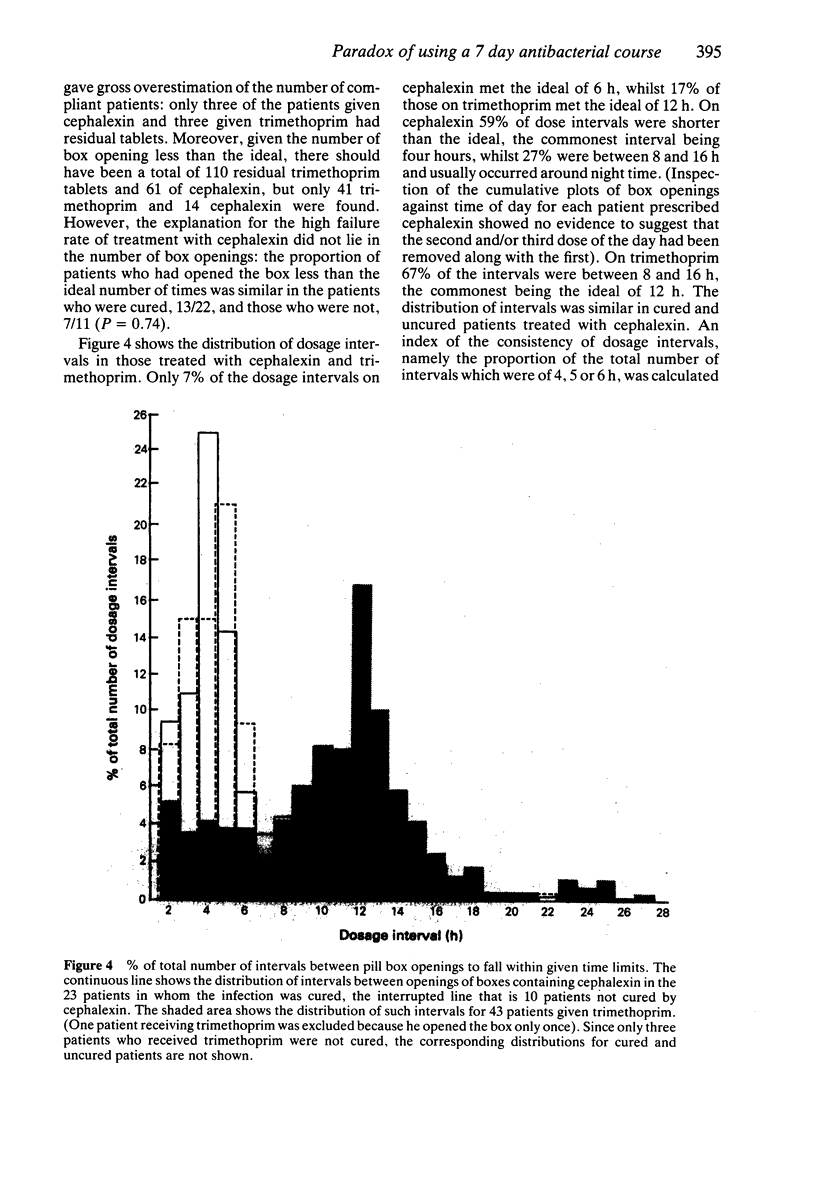

1. We have studied determinants of outcome of 7 day courses of treatment in 77 middle aged and elderly patients, in whom the general practitioner's diagnosis of urinary tract infections had been confirmed microbiologically. Bacteria were sensitive to cephalexin or trimethoprim. Where there was no preference, treatments were allocated randomly. Compliance was monitored using a pill box with a concealed electronic device which recorded openings of the box. 2. Prescribing trimethoprim, 200 mg twice daily, was more effective than cephalexin, 250 mg four times daily (cure rates 93 and 67%) (P less than 0.006). Those cured and not cured were not distinguished by age, gender, genitourinary history, or infecting organism. 3. Compliance as measured by box openings was worse for cephalexin than for trimethopim (P = 0.01). However, both totality and pattern of compliance were similar in patients cured and not cured by cephalexin. Thus rigid adherence to a conventional course did not promote cure: fewer doses could have been prescribed. 4. Estimating compliance is essential to clinical trials where medication is self-administered. Poor compliance may establish over exacting regimens. Counting box openings did overestimate compliance, but counting residual tablets overestimated it grossly: given the number of openings less than the ideal, there should have been 171 residual tablets, only 55 were found.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Bauer A. W., Kirby W. M., Sherris J. C., Turck M. Antibiotic susceptibility testing by a standardized single disk method. Am J Clin Pathol. 1966 Apr;45(4):493–496. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brauner A., Dornbusch K., Hallander H. O. beta-lactamase production by strains of Escherichia coli of intermediate susceptibility to beta-lactam antibiotics. A study of their clinical significance in urinary tract infection. Scand J Infect Dis Suppl. 1978;(13):67–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brumfitt W., Pursell R. Double-blind trial to compare ampicillin, cephalexin, co-trimoxazole, and trimethoprim in treatment of urinary infection. Br Med J. 1972 Jun 17;2(5815):673–676. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.5815.673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardenas J., Quinn E. L., Rooker G., Bavinger J., Pohlod D. Single-dose cephalexin therapy for acute bacterial urinary tract infections and acute urethral syndrome with bladder bacteriuria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1986 Mar;29(3):383–385. doi: 10.1128/aac.29.3.383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cockburn J., Gibberd R. W., Reid A. L., Sanson-Fisher R. W. Determinants of non-compliance with short term antibiotic regimens. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1987 Oct 3;295(6602):814–818. doi: 10.1136/bmj.295.6602.814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans L., Spelman M. The problem of non-compliance with drug therapy. Drugs. 1983 Jan;25(1):63–76. doi: 10.2165/00003495-198325010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang L. S., Tolkoff-Rubin N. E., Rubin R. H. Localization and antibiotic management of urinary tract infection. Annu Rev Med. 1979;30:225–239. doi: 10.1146/annurev.me.30.020179.001301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gower P. E., Tasker P. R. Comparative double-blind study of cephalexin and co-trimoxazole in urinary tract infections. Br Med J. 1976 Mar 20;1(6011):684–686. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.6011.684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood D., O'Grady F. Letter: Co-trimoxazole and cephalexin in urinary tract infection. Br Med J. 1976 May 1;1(6017):1073–1073. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.6017.1073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding G. K., Marrie T. J., Ronald A. R., Hoban S., Muir P. Urinary tract infection localization in women. JAMA. 1978 Sep 8;240(11):1147–1151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones R. H. Single-dose and seven-day trimethoprim and co-trimoxazole in the treatment of urinary tract infection. J R Coll Gen Pract. 1983 Sep;33(254):585–589. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacey R. W., Simpson M. H., Lord V. L., Fawcett C., Button E. S., Luxton D. E., Trotter I. S. Comparison of single-dose trimethoprim with a five-day course for the treatment of urinary tract infections in the elderly. Age Ageing. 1981 Aug;10(3):179–185. doi: 10.1093/ageing/10.3.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moulding T. S. The unrealized potential of the medication monitor. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1979 Feb;25(2):131–136. doi: 10.1002/cpt1979252131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norell S. E. Methods in assessing drug compliance. Acta Med Scand Suppl. 1984;683:35–40. doi: 10.1111/j.0954-6820.1984.tb08712.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preiksaitis J. K., Thompson L., Harding G. K., Marrie T. J., Hoban S., Ronald A. R. A comparison of the efficacy of nalidixic acid and cephalexin in bacteriuric women and their effect on fecal and periurethral carriage of enterobacteriaceae. J Infect Dis. 1981 Apr;143(4):603–608. doi: 10.1093/infdis/143.4.603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas V., Shelokov A., Forland M. Antibody-coated bacteria in the urine and the site of urinary-tract infection. N Engl J Med. 1974 Mar 14;290(11):588–590. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197403142901102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]