Abstract

Natural, synthetic and environmental estrogens have numerous effects on the development and physiology of mammals. Estrogen is primarily known for its role in the development and functioning of the female reproductive system. However, roles for estrogen in male fertility, bone, the circulatory system and immune system have been established by clinical observations regarding sex differences in pathologies, as well as observations following menopause or castration. The primary mechanism of estrogen action is via binding and modulation of activity of the estrogen receptors (ERs), which are ligand-dependent nuclear transcription factors. ERs are found in highest levels in female tissues critical to reproduction, including the ovaries, uterus, cervix, mammary glands and pituitary gland. Since other affected tissues have extremely low levels of ER, indirect effects of estrogen, for example induction of pituitary hormones that affect the bone, have been proposed. The development of transgenic mouse models that lack either estrogen or ER have proven to be valuable tools in defining the mechanisms by which estrogen exerts its effects in various systems. The aim of this article is to review the mouse models with disrupted estrogen signaling and describe the associated phenotypes.

Keywords: estrogen receptor, estrogen receptor knockout, transgenic

Reproductive phenotypes of estrogen receptor knockout models

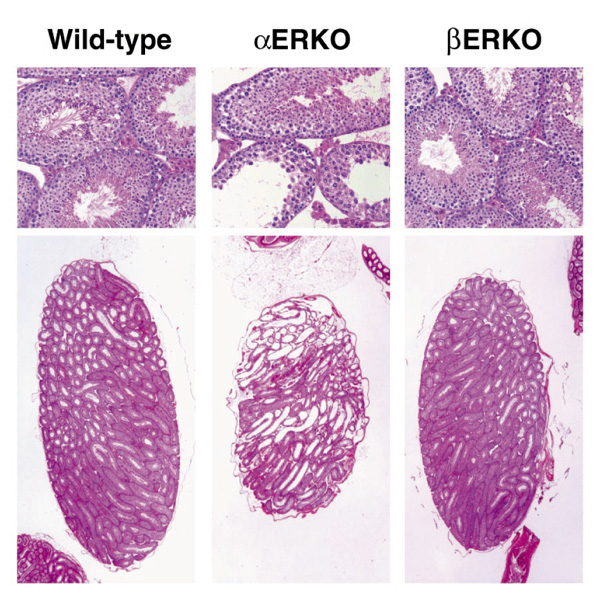

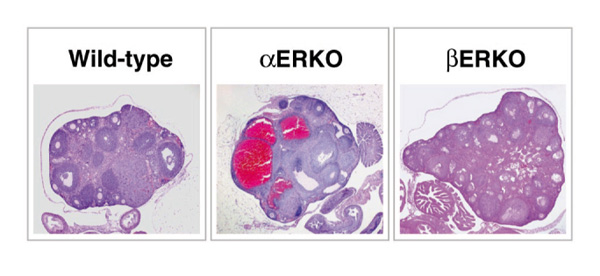

Estrogen has many roles in reproduction, and the generation of the estrogen receptor (ER)α and ERβ knockout (αERKO and βERKO) mice has further illustrated its roles and mechanisms. Interestingly, both sexes of the αERKO mice are infertile, whereas only the βERKO female has shown impaired fertility. In the male αERKO mice, infertility is due to deficits at several points in the reproductive process, including severe reduction in sperm numbers and lack of sperm function, as well as abnormal sexual behavior. The seminiferous tubules of the αERKO testes show progressive dilation that is accompanied by degeneration of the seminiferous epithelium (Fig. 1) [1*,2*]. Transplanted αERKO sperm was functional when developed in normal host testes [3**]. In contrast, the testes of the βERKO mice appear normal (Fig. 1), and produce sufficient and functional sperm to allow fertility, resulting in production of offspring in mice examined to date. Therefore, ERα appears to be more critical than ERβ in mediation of the estrogen actions necessary for maintenance of healthy testicular structures and the somatic cell function required for successful sperm maturation.

Figure 1.

Pathology of adult αERKO and βERKO testes. Sections from wild-type and ER-disrupted testes were stained with hematoxylin and eosin for comparison of their pathology. The wild-type and βERKO testes are indistinguishable, while the αERKO testis shows degeneration of the testicular structures.

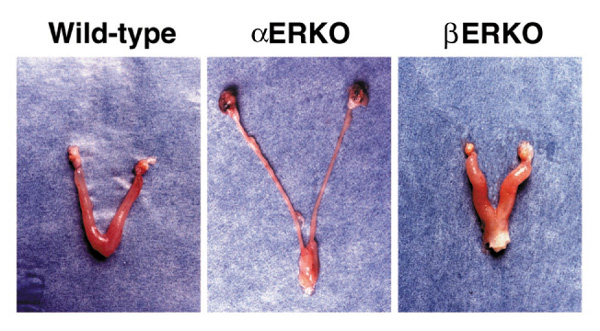

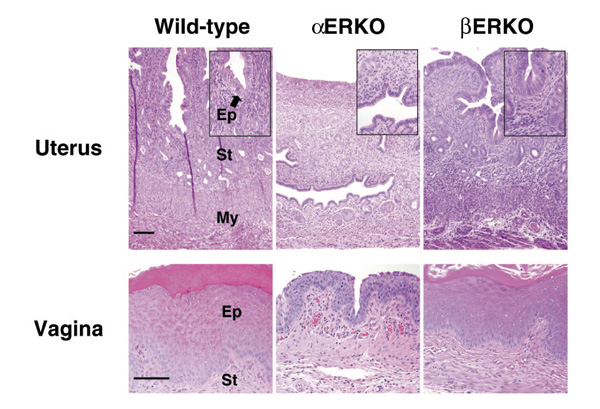

Normally, the female rodent reproductive tract grows and matures in response to cycling ovarian hormones, including estradiol. The growth and maturation of the epithelial portion and the preparation of the stromal layer is thought to be important for successful implantation and pregnancy to occur. The infertility of the female αERKO mouse is due in part to the insensitivity of the uterus to the mitogenic and differentiative actions of estrogen [4**,5**] (Fig. 2). Microscopic evaluation of the αERKO uterine tissue indicates that all expected tissues are present but appear immature, as illustrated by a reduced number of glands in the endometrium (Fig. 3). ERα is thus not necessary for development of the uterus, but is necessary for complete maturation and function of the tissue. In contrast, the wild-type and βERKO uteri are indistinguishable, and show normal organization and development of the stromal, myometrial and epithelial layers (Fig. 3), as well as glandular structures. ERβ is thus apparently not required for normal development of the female reproductive tract. Furthermore, when challenged with estrogenic compounds, the wild-type and βERKO uteri respond comparably with increased weight and epithelial development, while the αERKO uterus is nonresponsive. The uterus of the βERKO mouse is fully functional, as pregnancies are successfully carried to term and delivered. The vaginal tissue of the βERKO female is also similar in the wild type, with indications of cornification, an estrogen response, whereas the vaginal tissue of the αERKO female remains immature and is not cornified.

Figure 2.

Gross morphology of adult ERKO female reproductive tracts. Reproductive tracts dissected from wild-type and βERKO animals are normal, while the αERKO uterus is immature and the ovaries are enlarged and dark-colored due to hemorrhagic cysts.

Figure 3.

Uterine and vaginal histology of adult ERKO mice. Histological analysis of the uterus (top panels) and vagina (bottom panels) shows the βERKO tissue is indistinguishable from the wild type, showing the normal organization of the uterine tissue into the epithelial (Ep), stromal (St) and myometrial (My) compartments. In contrast, the αERKO uterine tissue is composed of all three layers, yet they are all immature and hypoplastic. Note also the glands are fewer in number. The vagina of the wild-type and βERKO mice is identical and cornified, indicating response to estrogen, while the αERKO vagina shows no cornification. (Reproduced with permission from Couse and Korach [5**].)

Ovary and ovarian hormones

Numerous intraovarian effects of locally synthesized estrogens have been described and postulated to be essential to ovarian function, including modifications in ER levels [6], DNA synthesis and cell proliferation [7, 8, 9,10,11], intercellular gap junctions [12], and follicular atresia [13]. Estradiol is also known to augment the actions of follicle-stimulating hormone on granulosa cells, resulting in the maintenance of follicle-stimulating hormone receptor levels [14,15] and the acquisition of luteinizing hormone (LH) receptor [16,17], an event critical to successful ovulation. The intraovarian actions of estradiol act to ultimately enhance follicular responsiveness to gonadotropins, and thereby result in increased aromatase activity and further estrogen synthesis [17,18]. Therefore, given the many speculated intraovarian actions of 17β-estradiol, disruption of the respective ER genes may be expected to result in distinct ovarian phenotypes.

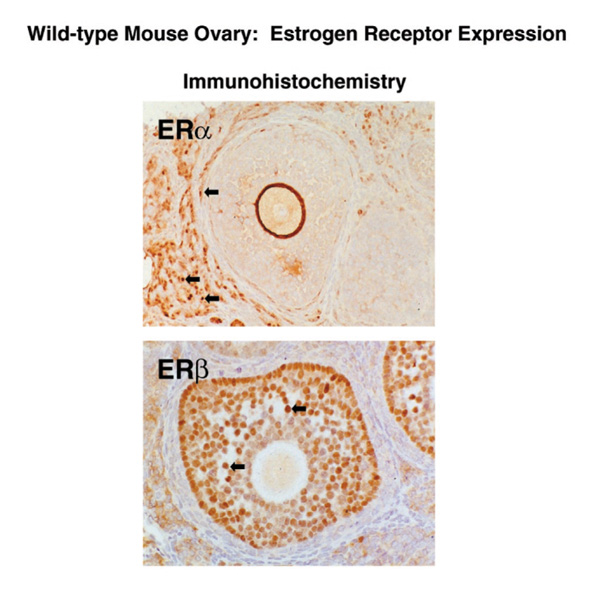

The ovarian phenotypes are a major component of the infertility in the αERKO mice and the subfertility in the βERKO mice. The αERKO female does not ovulate, while the βERKO female is subfertile with reduced litter numbers and smaller litter sizes compared with wild-type littermates. Interestingly, although both ERα and ERβ are detected in the ovary, their localization differs with ERβ in the granulosa cells and ERα in the theca and interstitial cells of the ovary [19*] (Fig. 4). The differential expression of these receptors makes compensatory activity of one receptor in the absence of the other unlikely.

Figure 4.

Localization of ERα and ERβ protein in the ovary. Serial sections from mouse ovary were stained with antibody to ERα (top panel) or ERβ (bottom panel). Note that ERβ immunoreativity is confined to the granulosa cells of the follicle, while ERα immunoreativity is localized in the thecal and interstitial cells of the ovary.

The hallmark phenotype of the αERKO female is the enlarged hemorrhagic cystic ovary (Fig. 5), although the prepubertal αERKO ovary looks similar to its wild-type littermate. This phenotype begins to develop progressively as the animal matures and is apparently due to a lack of estradiol feedback inhibition in the pituitary, which results in chronically elevated LH and subsequent hyperstimulation of the ovary (Table 1). This indicates that ERα is responsible for mediating the LH feedback inhibition in the hypothalamic-pituitary axis. The constant LH stimulation in the αERKO mice results in an abnormal endocrine environment in the αERKO female, with elevated estradiol and testosterone, and chronic preovulatory basal progesterone levels (Table 1).

Figure 5.

Ovarian pathology of the ERKO mice. Histological analysis of the wild-type ovary shows normal follicular development and indications of ovulation. The αERKO ovary shows large cystic structures and arrested follicle development with no indication of ovulation, while the βERKO ovary shows development of follicles is occurring but with little indication of successful ovulation.

Table 1.

Serum hormone levels in adult wild-type and αERKO mice

| Female | Male | |||

| Hormone | Wild type | αERKO | Wild type | αERKO |

| Gonadal steroids | ||||

| Estradiol (pg/ml)† | 29.5 ± 2.5 | 84.3 ± 12.5* | 11.8 ± 3.4 | 12.9 ± 3.4 |

| Progesterone (ng/ml)† | 2.3 ± 0.6 | 4.0 ± 1.1 | 0.5 ± 0.3 | 0.3 ± 0.1 |

| Testosterone (ng/ml) | 0.4 ± 0.4 | 3.2 ± 0.6 | 9.3 ± 4.0 | 16.0 ± 2.3 |

| Anterior pituitary | ||||

| LH (ng/ml) | 0.3 ± 0.04 | 1.7 ± 0.3* | 2.4 ± 1.2 | 3.7 ± 0.7 |

| FSH (ng/ml) | 4.9 ± 0.6 | 5.4 ± 0.7 | 26.0 ± 1.4 | 30.0 ± 1.1 |

| Prolactin (ng/ml) | 18.8 ± 10.7 | 3.5 ± 1.3 | ND | ND |

Data presented as mean ± standard error of the mean. ERKO, Estrogen receptor knockout; FSH, follicle stimulating hormone; LH, luteinizing hormone; ND, not determined. †These values in the female are different than those reported by Couse et al [43*], which were carried out on pooled sera. The values above are the means from assays on individual samples and therefore are more likely to reflect the true levels in the two genotypes. *t-test, wild type versus ERKO, P < 0.001. Reproduced with permission from Couse and Korach [5**].

The βERKO ovaries produce normal serum levels of estradiol and testosterone, and the circulating serum gonadotropin levels are also normal (Table 2). However, the βERKO ovaries function suboptimally, as illustrated by the appearance of numerous unruptured follicles following superovulation. Attempts to superovulate the βERKO female results in some ovulation, but the number of oocytes released is reduced compared with wild-type females (Table 3). A role for ERβ in ovulation is thus indicated, but the mechanism is still being defined.

Table 2.

Phenotypes of αERKO and βERKO mice

| Observation | ||

| Tissue | αERKO | βERKO |

| Testis | Progressive dilation and degradation of tubules, low | Normal structure, normal sperm count and fertility |

| sperm count, nonfunctional sperm | ||

| Uterus | Immature, unresponsive to estradiol | Normal development and response to estrogen |

| Ovary | Enlarged, hemorrhagic cysts, follicles arrested at | Subfertile, infrequent and inefficient ovulation; normal |

| preantral stage, no corpora lutea, no ovulation, elevated | estrogen and T | |

| serum estrogen and T levels | ||

| Mammary, female | Ducts do not develop beyond epithelial rudiment at | Normal, fully functional. Able to nurse offspring |

| nipple, no alveolar development | ||

| Pituitary | FSHβ, LHβ, αGSU, mRNAs all elevated, prolactin | Normal serum gonadotropin levels |

| mRNA reduced | ||

| Cardiovascular (male) | Lower basal nitric oxide, estrogen protection in vascular | ? |

| injury not lost. Increase in calcium channels, delayed | ||

| cardiac depolarization | ||

| Bone | Shorter; female, smaller diameter; male, lower density | Normal |

| Brain | Male, no intromission, ejaculation decreased agression; | Normal sexual behavior |

| female, no receptive behaviors | ||

ERKO, Estrogen receptor knockout; FSH, follicle-stimulating hormone; αGSU, gonadotrophin subunit alpha; LH, luteinizing hormone; T, testosterone.

Table 3.

Fertility and superovulation data in the βERKO female mice

| Continuous mating results | Superovulation results | |||||

| Genotype | n | Litters/female | Pups/litter | n | Mean | Range |

| Wild type | 6 | 2.8 ± 0.4 | 8.8 ± 2.5 | 10 | 33.7 ± 4.8 | 9-57 |

| Heterozygous | ND | ND | ND | 11 | 52.5 ± 5.7* | 20-77 |

| βERKO | 11 | 1.7 ± 1.0* | 3.1 ± 1.8** | 11 | 6.0 ± 1.5* | 0-13 |

Data presented as mean ± standard error of the mean. ERKO, Estrogen receptor knockout; ND, not determined. Reproduced from Couse and Korach [5**]. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.001 Student's two tailed t-test versus wild type.

Mammary gland

The mammary gland develops and functions in response to ovarian hormones, most notably estrogen and progesterone [20]. The female mammary gland is immature at birth and consists of a mainly stromal tissue, with only a rudimentary epithelial duct structure emanating from the nipple. The ducts elongate in response to ovarian and pituitary hormones, eventually filling the stromal tissue with a branched tree-like structure. Lobular alveolar buds develop along the length of these ducts during pregnancy and differentiate into secretory lactational structures.

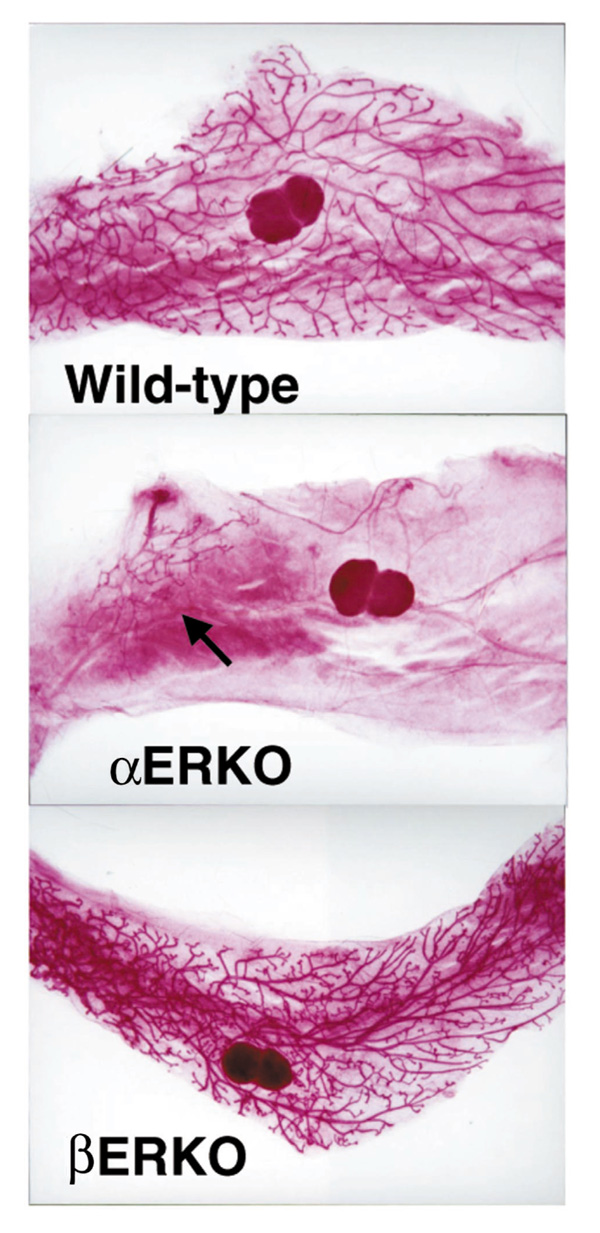

Transgenic knockout models have been very informative in understanding the roles of estrogen and progesterone in mammary gland development. The role of progesterone is indicated by the lack of development of alveolar buds in the progesterone receptor knockout mouse [21**]. Similarly, the role for ERα is illustrated by the lack of pubertal growth of the epithelial ductal rudiment in the αERKO female despite elevated circulating serum estradiol levels [22, 23] (Table 1 and Fig. 6). Transplantation of a wild-type pituitary under the kidney capsule of an αERKO female resulted in growth and development of the αERKO mammary epithelium. Removal of ovarian steroids by castration prevented the growth and development of mammary epithelium following pituitary transplant (Bocchinfuso et al, submitted). Administration of progesterone together with estradiol to an ovexed αERKO mouse resulted in alveolar development and some ductal elongation (Bocchinfuso et al, submitted). These observations indicate that the αERKO pituitary in the absence of ovarian hormones is incapable of providing a hormonal environment necessary for mammary development. In addition, the αERKO mammary gland epithelium is capable of responding with growth when a normally functioning pituitary is present to provide the necessary signals to the ovary and the mammary gland. Finally, it is apparent that the secretion of ovarian hormones is a required element of ductal elongation in the αERKO mouse. The βERKO mammary gland is similar to wild-type littermates [5**] (Fig. 6) and is functional because βERKO mothers are able to nurse their litters. Our observations suggest that ERβ is not required for the structural and functional development of the mammary gland.

Figure 6.

Mammary gland whole mounts from ERKO mice. An adult βERKO mouse displays a fully developed ductal network similar to the wild type. In contrast, the αERKO mouse has only a rudimentary underdeveloped epithelial duct (arrow).

Skeletal and cardiovascular tissue

Clinical as well as experimental data imply a role for estrogen as well as other endocrine factors in maintaining bone mass. For example, menopause or castration increases the rate of osteoporosis progression in women [24]. The ERKO model is a very useful tool for elucidating the mechanism of estrogen effects in bone and whether these effects are mediated, directly or indirectly, through ERs. ERα is present at very low levels in the bone cells. In the αERKO female, the bone is normal in terms of density, but it is significantly shorter and smaller in diameter in both sexes of the αERKO mice. This indicates the possibility of a role for estrogen in bone lengthening [5**]. A recent report has indicated αERKO mice have insulin-like growth factor-1 levels 30% lower than normal mice [25], which might account for the shorter bone. However, the altered hormonal environment (elevated estradiol and testosterone; see Table 1) as well as the increased body weight of the αERKO mouse should also be considered when interpreting this phenotype. The αERKO males do show a decrease in bone mineral density, a phenotype that is similar to one clinical case of estrogen insensitivity in a man [26]. Our current evaluation of the bones of the βERKO mouse shows no apparent difference from the wild type (unpublished data), indicating the lack of a major role for ERβ in bone physiology.

A role for estrogen in the cardiovascular system has also been implied by clinical observations correlating hormonal status with cardiovascular disease risk factors [27]. Additionally, ER has been detected in the vasculature [28]. In the αERKO male heart, an increased number of calcium channels [29*] and an associated delay in cardiac depolarization have been observed. In the αERKO vasculature, lower basal nitric oxide activity is detected [30] and, interestingly, the ability of estrogen to play a protective role in a vascular injury model is not lost in the αERKO [31*] or the βERKO [32*] mice. These observations suggest either that each receptor can compensate for the loss of the other or that another mechanism results in protection.

Progesterone action in the alpha ERKO female

The activities of estrogen and progesterone are interdependent in the female reproductive cycle [33]. The level of estrogen in the serum peaks just prior to ovulation. This estrogen 'spike' acts upon the uterus, initiating growth and maturation in preparation for pregnancy. Following ovulation, the level of progesterone rises and prepares the uterine stroma for implantation and decidualization, which is a transformation of the stromal cells in response to apposition of the conceptus. Both hormones have been shown to be essential for successful ovulation and pregnancy to occur. The actions of progesterone, like those of estrogen, are mediated through a specific nuclear transcription factor, the progesterone receptor (PR). Since the level of PR is regulated, in part, by estrogen, the activity of progesterone in αERKO tissues has been studied to determine whether disruption of αER signaling alters PR signaling. These observations have been reported in detail [34**], but will be summarized here. PR is present at a basal level in the αERKO uterus at about 60% of the wild-type level, and its mRNA is not increased by estrogen treatment. However, this basal level of PR is sufficient to induce the mRNA of the progesterone-responsive calcitonin and amphiregulin genes. The αERKO uterus can also be induced to undergo a decidual reaction in response to progesterone and physical trauma, indicating that PR is fully functional both biochemically and physiologically, and is not dependent on ERα for expression or function. Interestingly, the decidual reaction is estrogen dependent in the wild-type mice, but not in the αERKO mice.

The mammary gland also responds to progesterone, with development of lobular alveolar structures in the epithelium in preparation for lactation. Although the mammary epithelium of the αERKO mouse is underdeveloped, it can be stimulated with progesterone to develop lobular alveolar structures, suggesting that although the PR is regulated by estrogen, the basal level of PR present in the αERKO mammary gland is sufficient to mediate progesterone action. The necessity for estrogen induction of PR for progesterone responsiveness is brought into question by these observations. As reported previously [34**], it is possible that the need for estrogen priming is lost in the αERKO mice because of developmental differences. Although these progesterone responses have not been characterized in the βERKO mice, females can carry pregnancies to term and lactate normally, implying that the ability of the uterus and mammary gland to respond to progesterone is normal.

Ligand-independent signaling

Numerous studies have shown that nuclear steroid receptors can be activated by membrane receptor pathways to mediate genomic and physiologic responses in the absence of steroid ligand (reviewed in [35**]). This mechanism is initiated when growth factors bind to and activate their membrane receptor, resulting in activation of a phosphorylation cascade, culminating in modulation of nuclear receptor activity, most likely by phosphorylation of the nuclear receptor protein. These studies are summarized and described in detail elsewhere [36*]. In the case of ERα, we have reported activation by either epidermal growth factor (EGF) or insulin-like growth factor-1 [36*, 37, 38*, 39, 40, 41]. The αERKO mouse has allowed us to show that estrogen-like effects of EGF require the ERα in vivo, as EGF induced PR mRNA and thymidine incorporation only in uteri from wild-type mice, indicating that the αERKO mouse was totally unresponsive. Further biochemical studies indicate that the EGF receptor is present and the pathway is functional in the αERKO mouse, as EGF induced cFOS, an EGF-responsive gene [36*].

Summary

The phenotypes observed in the αERKO and βERKO mice illustrate the roles of ERα and ERβ in both reproductive and nonreproductive tissues. Although some phenotypes are downstream results of the lack of estrogen signaling (ie chronic LH stimulation of the αERKO ovary due to loss of estrogen-mediated negative feedback regulation of LH in the pituitary), we have learned a great deal about the roles of ERα and ERβ in development and physiology. Continued evaluation and characterization of the phenotypes of both classical estrogen target tissues, as well as other organ systems, should help to uncover previously unconsidered links of estrogen and other signaling pathways. Finally, our recent generation of mice lacking both ERs (αβERKO) will be useful in detecting any interaction between these receptors or compensatory mechanisms of one receptor in the absence of the other, as well as uncovering nonreceptor-mediated estrogen actions [42**].

References

- Eddy EM, Washburn TF, Bunch DO, Goulding EH, Gladen BC, Lubahn DB, Korach KS. Targeted disruption of the estrogen receptor gene in male mice causes alteration of spermatogenesis and infertility. . Endocrinology. 1996;137:4796–4805. doi: 10.1210/endo.137.11.8895349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess RA, Bunick D, Lee KH, Bahr J, Taylor JA, Korach KS, Lubahn DB. A role for oestrogens in the male reproductive system. . Nature. 1997;390:509–512. doi: 10.1038/37352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahato D, Goulding EH, Korach KS, Eddy EM. Spermatogenic cells do not require estrogen receptor alpha for development or function. . Endocrinology. 2000;141:1273–1276. doi: 10.1210/endo.141.3.7439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lubahn DB, Moyer JS, Golding TS, Couse JF, Korach KS, Smithies O. Alteration of reproductive function but not prenatal sexual development after insertional disruption of the mouse estrogen receptor gene. . Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:11162–11166. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.23.11162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couse JF, Korach KS. Estrogen receptor null mice: what have we learned and where will they lead us? Endocr Rev. 1999;20:358–417. doi: 10.1210/edrv.20.3.0370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards JS. Estradiol receptor content in rat granulosa cells during follicular development: modification by estradiol and gonadotropins. . Endocrinology. 1975;97:1174–1184. doi: 10.1210/endo-97-5-1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards JS. Maturation of ovarian follicles: actions and interactions of pituitary and ovarian hormones on follicular cell differentiation. . Physiol Rev. 1980;60:51–89. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1980.60.1.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao MC, Midgley AR, Jr, Richards JS. Hormonal regulation of ovarian cellular proliferation. . Cell. 1978;14:71–78. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(78)90302-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldenberg RL, Vaitukaitis JL, Ross GT. Estrogen and follicle stimulation hormone interactions on follicle growth in rats. . Endocrinology. 1972;90:1492–1498. doi: 10.1210/endo-90-6-1492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bley MA, Saragueta PE, Baranao JL. Concerted stimulation of rat granulosa cell deoxyribonucleic acid synthesis by sex steroids and follicle-stimulating hormone. . J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 1997;62:11–19. doi: 10.1016/s0960-0760(97)00021-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reilly CM, Cannady WE, Mahesh VB, Stopper VS, De Sevilla LM, Mills TM. Duration of estrogen exposure prior to follicle-stimulating hormone stimulation is critical to granulosa cell growth and differentiation in rats. . Biol Reprod. 1996;54:1336–1342. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod54.6.1336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burghardt RC, Anderson E. Hormonal modulation of gap junctions in rat ovarian follicles. . Cell Tissue Res. 1981;214:181–193. doi: 10.1007/BF00235155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsueh AJ, Billig H, Tsafriri A. Ovarian follicle atresia: a hormonally controlled apoptotic process. . Endocr Rev. 1994;15:707–724. doi: 10.1210/edrv-15-6-707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonetta SA, Spicer LJ, Ireland JJ. CI628 inhibits follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH)-induced increases in FSH receptors of the rat ovary: requirement of estradiol for FSH action. . Endocrinology. 1985;116:715–722. doi: 10.1210/endo-116-2-715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonetta SA, diZerega GS. Intragonadal regulation of follicular maturation. Endocr Rev. 1989;10:205–229. doi: 10.1210/edrv-10-2-205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessel B, Liu YX, Jia XC, Hsueh AJ. Autocrine role of estrogens in the augmentation of luteinizing hormone receptor formation in cultured rat granulosa cells. . Biol Reprod. 1985;32:1038–1050. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod32.5.1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang XN, Greenwald GS. Synergistic effects of steroids with FSH on folliculogenesis, steroidogenesis and FSH- and hCG-receptors in hypophysectomized mice. . J Reprod Fertil. 1993;99:403–413. doi: 10.1530/jrf.0.0990403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang LZ, Adashi EY, Hsuch AJ. Direct enhancement of gonadotropin-stimulated ovarian estrogen biosynthesis by estrogen and clomiphene citrate. . Endocrinology. 1982;110:2219–2221. doi: 10.1210/endo-110-6-2219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sar M, Welsch F. Differential expression of estrogen receptor-beta and estrogen receptor-alpha in the rat ovary. . Endocrinology. 1999;140:963–971. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.2.6533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imagawa W, Yang J, Guzman R, Nandi S. Control of mammary development. In The Physiology of Reproduction Edited by Knobil E, Neil JD, Ewing LL, Greenwald GS, Markert CL, Pfaff DW New York: Raven Press. 1994. pp. 1033–1063.

- Lydon JP, DeMayo FJ, Funk CR, Mani SK, Hughes AR, Montgomery CA, Shyamala G, Conneely OM, O'Malley BW. Mice lacking progesterone receptor exhibit pleiotropic reproductive abnormalities. . Genes Dev . 1995;9:2266–2278. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.18.2266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korach KS, Couse JF, Curtis SW, Washburn TF, Lindzey J, Kimbro KS, Eddy EM, Migiaccio S, Snedeker SM, Lubahn DB, Schomberg DW, Smith EP. Estrogen recpeptor gene disruption: molecular characterization and experimental and clinical phenotypes. In Recent Progress in Hormone Research Edited by Conn PM Bethesda,MD: The Endocrine Society. 1996. pp. 159–188. [PubMed]

- Bocchinfuso WP, Korach KS. Mammary gland development and tumorigenesis in estrogen receptor knockout mice. . J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 1997;2:323–334. doi: 10.1023/a:1026339111278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komm BS, Bodine PV. The ongoing saga of osteoporosis treatment. . J Cell Biochem Suppl. 1998;31:277–283. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4644(1998)72:30/31+<277::AID-JCB33>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidal O, Lindberg M, Savendahl L, Lubahn DB, Ritzen EM, Gustafsson JA, Ohlsson C. Disproportional body growth in female estrogen receptor-alpha-inactivated mice. . Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;265:569–571. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.1711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith EP, Boyd J, Frank GR, Takahashi H, Cohen RM, Specker B, Williams TC, Lubahn DB, Korach KS. Estrogen resistance caused by a mutation in the estrogen-receptor gene in a man. . N Engl J Med. 1994;331:1056–1061. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199410203311604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett-Connor E, Wenger NK, Grady D, Mosca L, Collins P, Kornitzer M, Cox DA, Moscarelli E, Anderson PW. Hormone and nonhormone therapy for the maintenance of postmenopausal health: the need for randomized controlled trials of estrogen and raloxifene. . J Womens Health. 1998;7:839–847. doi: 10.1089/jwh.1998.7.839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karas RH, Baur WE, van Eickles M, Mendelsohn ME. Human vascular smooth muscle cells express an estrogen receptor isoform. FEBS Lett. 1995;377:103–108. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)01293-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson BD, Zheng W, Korach KS, Scheuer T, Catterall WA, Rubanyi GM. Increased expression of the cardiac L-type calcium channel in estrogen receptor-deficient mice. . J Gen Physiol. 1997;110:135–140. doi: 10.1085/jgp.110.2.135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubanyi GM, Freay AD, Kauser K, Sukovich D, Burton G, Lubahn DB, Couse JF, Curtis SW, Korach KS. Vascular estrogen receptors and endothelium-derived nitric oxide production in the mouse aorta. Gender difference and effect of estrogen receptor gene disruption. . J Clin Invest. 1997;99:2429–2437. doi: 10.1172/JCI119426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iafrati MD, Karas RH, Aronovitz M, Kim S, Sullivan TR, Jr, Lubahn DB, O'Donnell TF, Jr, Korach KS, Mendelsohn ME. Estrogen inhibits the vascular injury response in estrogen receptor alpha-deficient mice. . Nat Med. 1997;3:545–548. doi: 10.1038/nm0597-545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karas RH, Hodgin JB, Kwoun M, Krege JH, Aronovitz M, Mackey W, Gustafsson JA, Korach KS, Smithies O, Mendelsohn ME. Estrogen inhibits the vascular injury response in estrogen receptor beta-deficient female mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:15133–15136. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.26.15133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham JD, Clarke CL. Physiological action of progesterone in target tissues. . Endocr Rev. 1997;18:502–519. doi: 10.1210/edrv.18.4.0308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis SW, Clark J, Myers P, Korach KS. Disruption of estrogen signaling does not prevent progesterone action in the estrogen receptor or knockout mouse uterus. . Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:3646–3651. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.7.3646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cenni B, Picard D. Ligand-independent activation of steroid receptors: new roles for old players. . Trends Endocrinol Metab . 1999;10:41–46. doi: 10.1016/s1043-2760(98)00121-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis SW, Washburn T, Sewall C, DiAugustine R, Lindzey J, Couse JF, Korach KS. Physiological coupling of growth factor and steroid receptor signaling pathways: estrogen receptor knockout mice lack estrogen-like response to epidermal growth factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:12626–12630. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.22.12626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson KG, Takahashi T, Bossert NL, Walmer DK, McLachlan JA. Epidermal growth factor replaces estrogen in the stimulation of female genital-tract growth and differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA . 1991;88:21–25. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.1.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ignar Trowbridge DM, Nelson KG, Bidwell MC, Curtis SW, Washburn TF, McLachlan JA, Korach KS. Coupling of dual signaling pathways: epidermal growth factor action involves the estrogen receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:4658–4662. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.10.4658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ignar Trowbridge DM, Teng CT, Ross KA, Parker MG, Korach KS, McLachlan JA. Peptide growth factors elicit estrogen receptor-dependent transcriptional activation of an estrogen-responsive element. Mol Endocrinol. 1993;7:992–998. doi: 10.1210/mend.7.8.8232319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ignar-Trowbridge DM, Pimentel M, Teng CT, Korach KS, McLachlan JA. Cross talk between peptide growth factor and estrogen receptor signaling systems. . Environ Health Perspect. 1995;103 (suppl 7):35–38. doi: 10.1289/ehp.95103s735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ignar-Trowbridge DM, Pimentel M, Parker MG, McLachlan JA, Korach KS. Peptide growth factor cross-talk with the estrogen receptor requires the A/B domain and occurs independently of protein kinase C or estradiol. . Endocrinology. 1996;137:1735–1744. doi: 10.1210/endo.137.5.8612509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couse JF, Hewitt SC, Bunch DO, Sar M, Walker VR, Davis BJ, Korach KS. Postnatal sex reversal of the ovaries in mice lacking estrogen receptors alpha and beta. . Science. 1999;286:2328–2331. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5448.2328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couse JF, Curtis SW, Washburn TF, Lindzey J, Golding TS, Lubahn DB, Smithies O, Korach KS. Analysis of transcription and estrogen insensitivity in the female mouse after targeted disruption of the estrogen receptor gene. . Mol Endocrinol. 1995;9:1441–1454. doi: 10.1210/mend.9.11.8584021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]