Abstract

Intramolecular electron transfer between CuA and heme a in solubilized bacterial (Paracoccus denitrificans) cytochrome c oxidase was investigated by pulse radiolysis. CuA, the initial electron acceptor, was reduced by 1-methylnicotinamide radicals in a diffusion-controlled reaction, as monitored by absorption changes at 825 nm, followed by partial restoration of the absorption and paralleled by an increase in the heme a absorption at 605 nm. The latter observations indicate partial reoxidation of the CuA center and the concomitant reduction of heme a. The rate constants for heme a reduction and CuA reoxidation were identical within experimental error and independent of the enzyme concentration and its degree of reduction, demonstrating that a fast intramolecular electron equilibration is taking place between CuA and heme a. The rate constants for CuA → heme a ET and the reverse heme a → CuA process were found to be 20,400 s−1 and 10,030 s−1, respectively, at 25°C and pH 7.5, which corresponds to an equilibrium constant of 2.0. Thermodynamic and activation parameters of these intramolecular ET reactions were determined. The significance of the results, particularly the low activation barriers, is discussed within the framework of the enzyme's known three-dimensional structure, potential ET pathways, and the calculated reorganization energies.

INTRODUCTION

Cytochrome c oxidase (CcO) is the terminal enzyme in the respiratory chain of most aerobic organisms where it catalyzes the sequential four-electron transfer from cytochrome c, or c552 in the case of Paracoccus denitrificans, to dioxygen; for recent reviews, see Richter and Ludwig (1) and Wikström (2).

CcO has four redox active metal centers, a mixed-valence copper pair forming the so-called CuA center, the low-spin heme a, and heme a3 with CuB, which together form the binuclear center. CuA serves as the electron acceptor from cytochrome c. Electrons are transferred from CuA to heme a and subsequently to the binuclear center where O2 is reduced to water. The intramolecular electron transfer reactions are coupled to the translocation of protons across the membrane (3–9) by a mechanism that is still under discussion (5,10–12). The involvement of hydrogen-bonded water networks in proton transport in relation to ET, mainly the heme a/heme a3–CuB transition, has been discussed recently (13). The electrochemical proton gradient resulting from the redox reactions is finally used by ATP synthase to generate ATP.

The electron transfer reactions between cytochrome c and CcO and within CcO have been investigated by several methods (14–22). Alternative approaches include flow-flash experiments of the reaction of the electrostatic CcO/cytochrome c complex with O2 (23,24), time-resolved measurements of the reverse electron transfer from the binuclear center to the oxidized heme a and CuA upon photolysis of the three-electron reduced CO-inhibited enzyme (25) and light-induced electron injection into the oxidase (8,26–29) or the electrostatic cytochrome c/cytochrome oxidase complex (30–32). All these results support CuA being the electron acceptor from cytochrome c, which is then followed by ET to heme a.

Pulse radiolysis has been widely used to monitor intramolecular ET in several redox enzymes ranging from multicopper enzymes such as laccase, ascorbate oxidase, ceruloplasmin (33–35), and copper-containing nitrite reductase (36–40) to the heme containing cd1-nitrite reductase (41–44) as well as the multicentered xanthine oxidase (45–47). The method has also been applied to studying intramolecular ET in bovine CcO where it was demonstrated that 1-methylnicotinamide radicals reduce oxidized CuA in a diffusion-controlled process, followed by intramolecular equilibration between CuA and heme a (48,49).

The available high-resolution three-dimensional (3D) structures of both mammalian and bacterial cytochrome c oxidases (50–57) make a correlation of the ET reactivity more meaningful. Hence, we investigated the intramolecular ET thermodynamics and kinetics of the CuA-heme a equilibration using pulse radiolysis to correlate the internal ET reactivities with their known 3D structures.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

All chemicals were of analytical grade and used without further purification. Milli-Q water (Millipore, Eschborn, Germany) was used throughout the studies.

Enzyme preparation

Cytochrome c oxidase from P. denitrificans was isolated in detergent micelles according to Hendler et al. (58). The pure CcO fractions eluted from DEAE-Sepharose CL-6B (Amersham, Freiburg, Germany) with a NaCl-gradient in 20 mM KPi, 1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0, containing 0.4 mM DM (Glycon, Luckenwalde, Germany) at 4°C were concentrated with buffer-washed VivaSpin concentrators (50 kD CO from VicaScience, Hannover, Germany). A concentrated sample of 68 mg CcO in 4 ml of the elution medium was added to a small column with 4 ml Q Sepharose FastFlow (Amersham, Freiburg, Germany), equilibrated with 10 mM KPi and 0.5 mM DM pH 7.5 at 4°C, was washed with 100 ml of the same DM containing buffer. Elution with 600 mM KCl in 10 mM KPi and 0.5 mM DM pH 7.5 provided concentrated fractions of CcO. To remove KCl, the chosen fractions were dialyzed at 4°C in Spectra/Por CE tubing (50 kD CO from Spectrum Laboratories (Rancho Dominguez, CA), for 3 days against 10 mM KPi and 0.5 mM DM, pH 7.5 (three buffer changes). CcO concentration was determined at 425 nm on the basis of an extinction coefficient of 1.57 × 105 M−1cm−1. The activity, measured at 550 nm with 50 μM Na2S2O4-reduced horse-heart cytochrome c (Biomol, Hamburg, Germany) under substrate saturation conditions in the presence of 0.5 nM CcO in 10 mM KPi, 40 mM KCl, and 0.5 mM DM at 25°C and pH 7.5, provided a turnover number of 290 electrons s−1.

Determination of extinction coefficient

For the determination of the CuA extinction coefficient in 10 mM KPi and 0.5 mM DM pH 7.5 at 25°C, the visible spectrum of Na2S2O4-reduced CcO was subtracted from that of the oxidized enzyme, which exhibits a maximal value at 830 nm. The CuA extinction coefficient was 2140 M−1cm−1. The apparent absorption of the reduced form above 700 nm is due to light scattering contributions of the mixed protein/detergent micelle.

Kinetic measurements

Time-resolved measurements were carried out using the pulse radiolysis system based on the Varian V-7715 linear accelerator at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, Israel. Accelerated electrons (5 MeV) were employed using pulse lengths in the range from 0.1 to 1.5 μs in protein solutions containing 5 mM 1-methylnicotinamide (MNA+), 10 mM KPi, and 0.5 mM DM at pH 7.5. The yield of reducing MNA* radicals was ∼1.5 μM/μs pulse width. All measurements were carried out anaerobically in solutions saturated with and kept under purified argon at a pressure slightly in excess of atmospheric pressure. The detergent also serves as a scavenger for OH radicals. A 1-cm spectrosil cuvette was employed, using one or three light passes that result in an overall optical pathlength of either 1 or 3 cm, respectively. A 150-W xenon lamp produced the analyzing light beam together with a Bausch & Lomb (Rochester, NY) double grating monochromator. Appropriate optical filters with cutoff at 385 or 590 nm were used to reduce photochemical and light scattering effects. The data acquisition system consisted of a Tektronix (Beaverton, OR) 390 A/D transient recorder attached to a PC. The temperature of the reaction solutions in the cuvette (15 different temperatures in the range from 4.1 to 36.4°C) was controlled by a thermostating system, and continuously monitored by a thermocouple attached to the cuvette. Reactions were generally performed under pseudofirst-order conditions, with typically a 20-fold excess of oxidized protein over reducing radicals. In each experiment 2000 data points are collected, divided equally between two different timescales. Usually the processes were recorded over at least three half-lives. Each kinetic run was repeated at least four times. The data were analyzed by fitting to a sum of exponentials using a nonlinear least squares program written in MATLAB (The MathWorks, Natick, MA).

RESULTS

In the presence of an ∼100-fold excess of 1-methyl nicotinamide (MNA+) over protein and under anaerobic conditions, the hydrated electrons produced by the radiation pulse react with the former species to produce MNA* radicals almost quantitatively. Formation and decay of this radical can be monitored at 420 nm (ɛ420 = 3200 M−1cm−1) (44); the formation takes place in the microsecond timescale whereas its decay, by dismutation, takes place in the time range of milliseconds. The oxidized CuA center, which exhibits a weak and comparatively broad absorbance around 830 nm, was found to be reduced according to its absorption change monitored at 825 nm concomitantly with the disappearance of the MNA* radical. The rate constant for this intermolecular ET process depends, as expected under pseudofirst-order conditions, on the enzyme concentration being in excess and the bimolecular rate constant was calculated to be 3 × 109 M−1s−1 at 25°C, i.e., an essentially diffusion-controlled process. Successive pulses were introduced into the same protein solution causing the stepwise reduction of the oxidized enzyme. The reduction yield of the enzyme per pulse could be determined from the absorption changes of the fast CuA reduction phase. After adding two reduction equivalents to the enzyme solution, the Cu absorption at 825 nm becomes negligible, indicating that the initial reduction phase appears to be complete. Introducing additional pulses into the solution only led to MNA* formation followed by dismutation of these radicals, but no further absorption changes of the enzyme were observed.

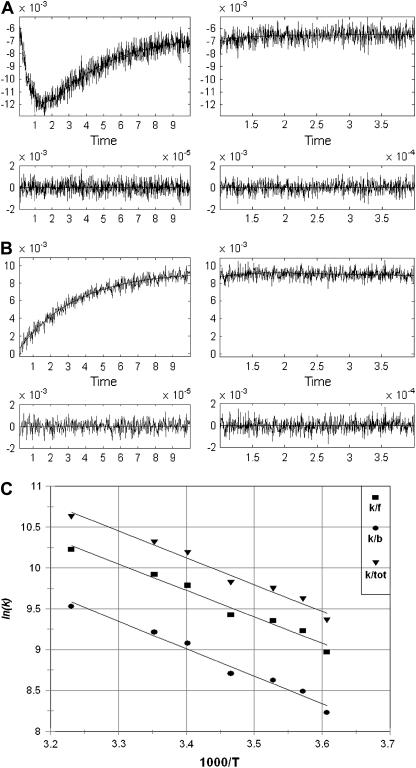

Under the conditions of incomplete reduction of the protein, subsequent to the fast bimolecular reduction of the binuclear copper center, the reduced CuA site was found to undergo partial reoxidation as revealed by an increase in absorption at 825 nm (Fig. 1 A). The observed rate constant kobs of this step is (3.05 ± 0.25) × 104 s−1 at 25°C (pH 7.5) and was found to be independent of enzyme concentration or its degree of reduction. Because this reaction step occurs simultaneously with an absorption increase at 605 nm (Fig. 1 B), where the reduced heme a absorbs predominantly (Δɛ605 = 18,600 M−1cm−1), we assign this reaction step to an intramolecular ET between reduced CuA [CuA(I)] and oxidized heme a [Fea(III)]. This is further substantiated by the observation that the amplitude ratio of the absorbance increases at 825 nm (CuA reoxidation) relative to that at 605 nm (heme a reduction) is as expected from their respective extinction coefficients. The process does not go to completion, however, and by determining the amplitudes of CuA reduction and reoxidation at 825 nm (cf. Fig. 1 A) an equilibrium constant was calculated for the reaction:

|

(1) |

at 25°C, leading to K = 2.0 ± 0.1. The experimentally observed rate constant of the equilibration process (Eq. 1) is the sum of the forward and the reverse ET steps: kobs = kf + kb. Because the equilibrium constant K is equal to kf/kb, the individual rate constants could be calculated. Equilibrium and rate constants of this reaction were determined as a function of temperature in the range from 4.1 to 36.4°C (Fig. 1 C), and the results are summarized in Table 1.

FIGURE 1.

Time-resolved absorption changes. In the left-hand panel the initial reaction phase is shown. The reaction is followed further at a slower timescale in the right panel. (A) CuA reduction and reoxidation monitored at 825 nm. Enzyme concentration, 52 μM; MNA concentration, 5 mM; argon saturated buffer, 10 mM phosphate, 0.5 mM DM, pH 7.5. Temperature, 298 K. Optical pathlength, 3 cm. Pulse width, 1.0 μs. (B) Heme a reduction monitored at 605 nm. Enzyme concentration, 15.4 μM; MNA concentration, 5 mM; argon saturated buffer, 10 mM phosphate, 0.5 mM DM, pH 7.5. Temperature, 298 K. Optical pathlength, 3 cm. Pulse width, 0.3 μs. (C) Temperature dependence of rate constants for the forward (kf), reverse (kb), and total (ktot) reaction as depicted in Eq. 1.

TABLE 1.

Kinetics and thermodynamics of CuA-heme a ET equilibration at 25° C and pH 7.5

| Kinetic parameters | k / s−1 | ΔH≠/kJ mol−1 | ΔS≠/J K−1 mol−1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Forward (bacterial)* | 20,400 ± 1500 | 22.2 ± 1.2 | −88 ± 2 |

| (bovine)† | 13,000 ± 1200 | 11.4 ± 0.9 | −128 ± 11 |

| Reverse (bacterial)* | 10,030 ± 800 | 24.6 ± 1.3 | −86 ± 2 |

| (bovine)† | 3700 ± 300 | 13.4 ± 1.0 | −131 ± 11 |

| Equilibrium data | K | ΔH0/kJ mol∼1 | ΔS0/J K∼1 mol∼1 |

| (bacterial)* | 2.0 ± 0.1 | −2.4 ± 0.7 | −2.6 ± 2.4 |

| (bovine)† | 3.4 ± 0.5 | −2.0 ± 0.3 | 3 ± 5 |

This work.

Farver et al. (49).

DISCUSSION

The reaction scheme for the ET processes monitored in this study can be depicted as follows:

|

(2) |

|

(3) |

|

(4) |

The MNA* radicals formed, as indicated in Eq. 2, reduce the CuA site in a diffusion-controlled bimolecular reaction (Eq. 3). The reduction of CuA was found to be followed by a rapid partial reduction of heme a (Eq. 4). The bimolecular rate constant of the reaction between the enzyme and MNA* of 3 × 109 M−1s−1 at 25°C is identical with that obtained earlier for bovine CcO (49). The reduction of heme a takes place by an intramolecular ET from reduced CuA, as evidenced by the simultaneous absorption changes taking place at 825 nm (CuA) and 605 nm, where heme a contributes ∼65% to the total absorption (cf. Fig. 4 in Hellwig et al. (59)). These time-resolved absorbance changes are illustrated in Fig. 1. The rate constant of the intramolecular electron transfer from CuA to heme a of (3.05 ± 0.25) × 104 s−1 observed here at 298 K is almost twice as large as that has been determined earlier for intramolecular ET in the bovine CcO (1.67 ± 0.23) × 104 s−1 (49). The latter value is similar to the reciprocal τ-value determined by Kobayashi et al. (48), also by employing pulse radiolysis. The equilibrium constant for the internal electron equilibration is K = 2.0 ± 0.1, i.e., half of the value determined earlier for the bovine protein (cf. Table 1). It is noteworthy that the activation enthalpies of the intramolecular ET in both proteins are quite small, and that the higher rate observed for the bacterial enzyme is therefore due to a more advantageous activation entropy. Studies of intramolecular ET reactivity in P. denitrificans CcO were performed in the presence of a detergent (18) and with a reconstituted system (8). The reported reciprocal τ-value of 4.6 × 104 s−1 obtained with the reconstituted enzyme is close to our results. Some studies of the Rhodobacter spheroides enzyme or its complex with cytochrome c (28,29,31) were characterized by higher rate constants than those observed for the P. denitrificans protein. All other investigations were done on the bovine enzyme in the pH range of 7.0–8.1, mostly close to room temperature and under low ionic strength conditions, with the free enzyme or its complex with CO or cytochrome c or in its chemically modified state. The majority of these studies provide only τ-values of the ET process (23,26,29,30,60) rather than specific rate constants of individual steps as reported here. Similar rate constants were reported or can be deduced for the bovine enzyme by Morgan et al. (25) and Szundi et al. (32). Although the hitherto published dynamic and thermodynamic parameters vary, they agree within one order of magnitude.

No direct reduction by free radicals of the heme a site, which is mainly shielded by the hydrophobic residues of the protein, was observed. Also, there is no indication in these experiments, under conditions where the enzyme is present in considerable stoichiometric excess, for reduction of the heme a3 site directly or by electron transfer from the reduced heme a or CuA, even on a 10-s timescale. Intramolecular ET between heme a and heme a3 would result in an absorbance decrease at 605 nm where heme a contributes considerably more to the absorption than heme a3. Heme a3 exhibits, in the case of the bacterial enzyme, a maximum value at 609 and a shoulder at 588 nm, as determined in the absence of inhibitors (59). Our observation that no changes could be resolved in absorption properties of the oxidized heme a3-CuB binuclear center is in full agreement with results of earlier studies where no reoxidation of heme a by the heme a3-CuB binuclear center was not observed (26,30,48,60). Still, it is noteworthy that in the presence of a large excess of reducing agent and absence of O2, Richter et al. (61) observed a comparatively slow process in the time range of seconds, which was assigned to the electron transfer between heme a and a3.

Heme a3 and CuB are strongly coupled, implying that separate reactivities of the individual components in electron transfer is not probable. As discussed by Wikström et al. (62,63) reduction of heme a3 by heme a should, in principle, be a very fast process provided that several conditions are fulfilled concerning protolytic reactions within the oxygen reduction site and possibly also the involvement of structural features. Thus, electron transfer from heme a to a3 cannot be excluded but, under the conditions of our study (excess oxidase over reductant) has not been observed within a time range of 10 s. Using published reduction potentials of the redox centers in CcO, and assuming no cooperativity between sites we find that a given number of added electrons at full equilibrium should be distributed in the following way: reduced CuA, 26%; reduced heme a, 53%; reduced heme a3, 21%. It has, however, been suggested earlier that the redox state of heme a does influence the potential of the heme a3/CuB couple, implying that coupling exists between these two centers (63). Therefore, assuming that the sites do interact, the potentials might change with electron uptake, making ET to heme-a3 less likely. Further, the path leading from CuA to heme a3 is much longer (12 covalent bonds and two H-bonds) than the CuA to heme a path (seven covalent bonds and two H-bonds). By careful examination of the stoichiometry of the reactions monitored, our results clearly demonstrate that under these experimental conditions, only two reduction equivalents are taken up by the enzymes. One rationale for this observation could thus be kinetic (weaker electronic coupling between CuA and heme a3-CuB) whereas the other rationale could be thermodynamic (reduction potentials).

Calculation of the equilibrium electron distribution from the difference in midpoint reduction potentials of hemes a and a3 of the P. denitrificans enzyme (at pH 7 and 5°C in the presence of 100 mM KCl) of 230 and 205 mV versus SHE (59), respectively, indicates that heme a reduction would be favored relative to that of heme a3. The ET process between heme a and heme a3 is likely to be influenced by conformational properties of the enzyme, and obviously in the presence of O2 additional driving force would promote this process. As already stressed, we have not been able to introduce more than two reduction equivalents into the enzyme, indicating that ET to the heme a3-CuB system does not take place under these experimental (i.e., anaerobic) conditions, which is in accordance with the above-mentioned reduction potentials.

The observed equilibrium constant of the rapid CuA/heme a electron exchange step (cf. Eq. 4) is 2.0 ± 0.1 at 25°C, pH 7.0, which corresponds to a difference in reduction potentials between the heme a [Fe(III)/Fe(II)] and CuA [Cu(II)/(I)] couples of +18 ± 1 mV. For CuA in the P. denitrificans CcO, a midpoint potential of 213 mV versus SHE was determined under the conditions mentioned above (P. Hellwig, Institute of Biophysics, J. W. Goethe-University, Frankfurt, Germany; personal communication, 2005). The equilibrium constant determined here is thus in excellent agreement with the differences between the reduction potentials of heme a and CuA (+17 mV = 230 − 213 mV).

The electron distribution at equilibrium between heme a and CuA exhibits an exceptionally small temperature dependence; thus we find ΔH0 = −2.4 ± 0.7 kJ mol−1 and ΔS0 = −2.6 ± 2.4 J K−1 mol−1. These very small values are also in good agreement with earlier results (49) obtained for the bovine CcO. The equilibrium and kinetic data enable us to calculate the activation parameters for both forward and reverse ET reactions between CuA and heme a (cf. Fig. 1 C and Table 1). For comparison, earlier results obtained for intramolecular ET in the bovine enzyme are also presented here.

Electron transfer between electron donor (D) and acceptor (A) in a weakly coupled system can be described by the semiclassical Marcus equation for nonadiabatic processes (64):

|

(5) |

where HDA is the electronic tunneling matrix element coupling D and A:

|

(6) |

is the maximal electronic coupling at van der Waals contact distance (r0). FC is the Franck-Condon factor, which in the classical limit (kBT > hν) is

is the maximal electronic coupling at van der Waals contact distance (r0). FC is the Franck-Condon factor, which in the classical limit (kBT > hν) is

|

(7) |

ΔG0 is the standard free-energy difference between D and A, λTOT is the reorganization energy required for changes in the nuclear configuration of the redox centers accompanying ET.

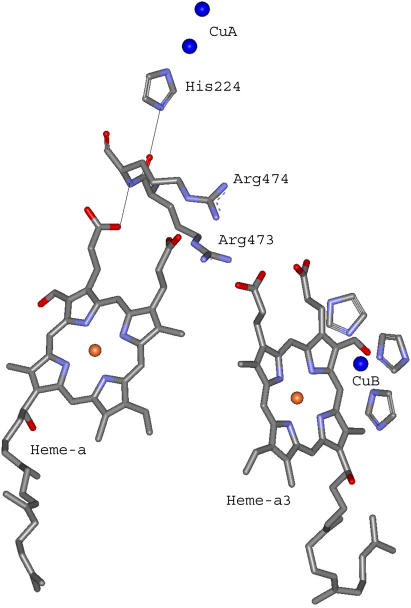

The optimal electron tunneling pathway (65) from CuA to heme a has been calculated using the HARLEM program (66) and proceeds via a hydrogen bond between the His-224 ligand and the carbonyl group of Arg-473. Another hydrogen bond connects the Arg-474 amide nitrogen to one of the heme a propionyl side chains (cf. Fig. 2). Altogether the path includes 14 covalent bonds and two hydrogen bonds (cf. Fig. 2). This corresponds to an effective tunneling length, σℓ = 2.52 nm and an electronic coupling decay factor, Π = 1.0 × 10−4. The metal-to-metal distance is 1.98 nm. The same pathway has been proposed for the bovine CcO for which we have calculated the electronic coupling energy, HDA, to be 2.9 × 10−6 eV (49) in good agreement with Brzezinski (67) who had estimated the electronic coupling energy between CuA and heme a to be 3.8 × 10−6 eV. From Eqs. 5 and 7 we now find λTOT = 0.32 eV, in rather good agreement with the value of 0.3 eV, estimated by Brzezinski (66). To account for the maximum (activationless) rate constant of 8 × 105 s−1, Ramirez et al. (68) calculated, from a driving force of 0.05 eV, that the value of the reorganization energy must be between 0.15 and 0.5 eV. Paula et al. (6) have estimated the lower limit of the electron transfer rate constant between CuA and heme a to be ∼2 × 105 s−1 during the reduction of O2 to water by fully reduced oxidase using the flow-flash method. Electron transfer between CuA and heme a was found to be limited by proton uptake (6), and the rate constant would correspond to a reorganization energy close to 0.3 eV (68), which is in good agreement with the value reported here. Finally, comparing the reorganization energies for internal ET in bacterial and bovine CcO it is interesting that in the former enzyme λTOT is smaller (0.32 eV) than in the latter (0.40 eV). Thus, the reason for the higher rate of internal ET in bacterial CcO is a smaller energy requirement for reorganization of the redox centers in P. denitrificans CcO. This is in accordance with the observation that in bovine CcO, the subunits containing the heme regions are possibly surrounded by additional water molecules that are not seen in the bacterial enzyme; the medium surrounding an active site in a metalloprotein will affect the reorganization energy associated with the ET reaction. Thus, a hydrophobic active site will lead to smaller reorganization energies than a hydrophilic one, and consequently the kinetics of intraprotein ET will be highly sensitive to the active site environment.

FIGURE 2.

Electron transfer pathway between CuA and heme a in P. denitrificans CcO. The center-to-center pathway consists of 14 covalent bonds and two hydrogen bonds. The figure is based on the published 3D structure of P. denitrificans CcO (50). The two CuA atoms (top) are bound to the protein subunit II, whereas heme a (left) and heme a3 (right) are bound to subunit I.

CONCLUSIONS

Analysis of both the time course and amplitudes of the intramolecular electron transport between CuA and heme a in bacterial cytochrome c oxidase has yielded the microscopic rate constants, activation parameters, and equilibrium constant as presented in Table 1. These results extend significantly the rigorous framework for understanding the electron transfer interactions between CuA and heme a.

The experimentally determined rate constants agree well with those theoretically calculated using results of previous work on intramolecular ET in both copper and heme containing proteins.

The ET process is characterized by an unusually small reorganization energy requirement.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the technical support provided by H. Müller, W. Müller, and A. Schacht. We thank P. Hellwig and A. Giuffrè for many interesting and helpful discussions as well as P. Hellwig for making unpublished data available to us. We thank Eran Gilad from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem for his excellent support in running the accelerator.

I.P. thanks the Minerva Foundation, Munich, Germany for its continued support. We also acknowledge financial support provided by the Max-Planck Society, the German Research Foundation (SFB 472), and the “Fond der Chemischen Industrie”.

Abbreviations used: CcO, cytochrome c oxidase; ET, electron transfer; MNA, 1-methyl nicotinamide; DM, n-dodecyl-β-d-maltoside.

References

- 1.Richter, O.-M. H., and B. Ludwig. 2003. Cytochrome c oxidase: structure, function, and physiology of a redox-driven molecular machine. Rev. Physiol. Biochem. Pharmacol. 147:47–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wikström, M. 2004. Cytochrome c oxidase: 25 years of the elusive proton pump. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1655:241–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wikström, M. K. F. 1977. Proton pump coupled to cytochrome c oxidase in mitochondria. Nature. 266:271–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Babcock, G. T., and M. Wikström. 1992. Oxygen activation and the conservation of energy in cell respiration. Nature. 356:301–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Michel, H., J. Behr, A. Harrenga, and A. Kannt. 1998. Cytochrome c oxidase: structure and spectroscopy. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 27:329–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paula, S., A. Sucheta, I. Szundi, and Ó. Einarsdóttir. 1999. Proton and electron transfer during the reduction of molecular oxygen by fully reduced cytochrome c oxidase: a flow-flash investigation. Biochemistry. 38:3025–3033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wikström, M. 2000. Mechanism of proton translocation by cytochrome c oxidase: a new four-stroke histidine cycle. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1458:188–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ruitenberg, M., A. Kannt, E. Bamberg, B. Ludwig, H. Michel, and K. Fendler. 2000. Single-electron reduction of the oxidized state is coupled to proton uptake via the K pathway in Paracoccus denitrificans cytochrome c oxidase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 97:4632–4636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wikström, M., and M. I. Verkhovski. 2002. Proton translocation by cytochrome c oxidase in different phases of the catalytic cycle. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1555:128–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Michel, H. 1998. The mechanism of proton pumping by cytochrome c oxidase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 95:12819–12824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Backgren, C., G. Hummer, M. Wikström, and A. Puustinen. 2000. Proton translocation by cytochrome c oxidase can take place without the conserved glutamic acid in subunit I. Biochemistry. 39:7863–7867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bloch, D., I. Belevich, A. Jasaitis, C. Ribacka, A. Puustinen, M. I. Verkhovsky, and M. Wikström. 2004. The catalytic cycle of cytochrome c oxidase is not the sum of its two halves. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 101:529–533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Olkhova, E., M. C. Hutter, M. A. Lill, V. Helms, and H. Michel. 2004. Dynamic water networks in cytochrome c oxidase from Paracoccus denitrificans investigated by molecular dynamics simulations. Biophys. J. 86:1873–1889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Greenwood, C., and Q. H. Gibson. 1967. The reaction of reduced cytochrome c oxidase with oxygen. J. Biol. Chem. 242:1782–1787. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wilson, M. T., C. Greenwood, M. Brunori, and E. Antonini. 1975. Kinetic studies on the reaction between cytochrome c oxidase and ferrocytochrome c. Biochem. J. 147:145–153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ferguson-Miller, S., D. Brautigam, and E. Margoliash. 1976. Correlation of the kinetics of electron transfer activity of various eukariotic cytochromes c with binding to mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase. J. Biol. Chem. 251:1104–1115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rieder, R., and H. R. Bosshard. 1980. Comparison of the binding sites on cytochrome c for cytochrome c oxidase, cytochrome bc1, and cytochrome c1. Differential acetylation of lysyl residues in free and complexed cytochrome c. J. Biol. Chem. 255:4732–4739. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ludwig, B., and Q. H. Gibson. 1981. Reactions of oxygen with cytochrome c oxidase from Paracoccus denitrificans. J. Biol. Chem. 256:10092–10098. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Antalis, T. M., and G. Palmer. 1982. Kinetic characterization of the interaction between cytochrome oxidase and cytochrome c. J. Biol. Chem. 257:6194–6206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bisson, R., G. C. M. Steffens, R. A. Capaldi, and G. Buse. 1982. Mapping the cytochrome c binding site on cytochrome c oxidase. FEBS Lett. 144:359–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Einarsdóttir, Ó., M. G. Choc, S. Weldon, and W. S. Caughey. 1988. The site and mechanism of dioxygen reduction in bovine heart cytochtrome c oxidase. J. Biol. Chem. 263:13641–13654. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Drosou, V., F. Malatesta, and B. Ludwig. 2002. Mutations in the docking site for cytochrome c on the Paracoccus heme aa3 oxidase. Eur. J. Biochem. 269:2980–2988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hill, B. C. 1991. The reaction of the electrostatic cytochrome c-cytochrome oxidase complex with oxygen. J. Biol. Chem. 266:2219–2226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hill, B. C. 1994. Modeling the sequence of electron transfer reactions in the single turnover of reduced, mammalian cyrochrome c oxidase with oxygen. J. Biol. Chem. 269:2419–2425. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morgan, J. E., P. M. Li, D.-J. Jang, M. Q. A. El-Sayed, and S. I. Chan. 1989. Electron transfer between cytochrome a and copper A in cytochrome c oxidase: a perturbed equilibrium study. Biochemistry. 28:6975–6983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nilsson, T. 1992. Photoinduced electron transfer from tris(2,2′-bipyridyl)ruthenium to cytochrome c oxidase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 89:6497–6501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brzezinski, P., and M. T. Wilson. 1997. Photochemical electron injection into redox-active proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 94:6176–6179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Konstantinov, A. A., S. Siletsky, D. Mitchell, A. Kaulen, and R. B. Gennis. 1997. The roles of the two proton input channels in cytochrome c oxidase from Rhodobacter sphaeroides probed by the effects of site-directed mutations on time-resolved electrogenic intraprotein proton transfer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 94:9085–9090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zaslavsky, D., R. C. Sadoski, K. Wang, B. Durham, R. B. Gennis, and F. Millett. 1998. Single electron reduction of cytochrome c oxidase compound F: resolution of partial steps by transient spectroscopy. Biochemistry. 37:14910–14916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Geren, L. M., J. R. Beasley, B. R. Fine, A. J. Saunders, S. Hibdon, G. J. Pielak, B. Durham, and F. Millett. 1995. Design of a ruthenium-cytochrome c derivative to measure electron transfer to the initial acceptor in cytochrome c oxidase. J. Biol. Chem. 270:2466–2472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang, K., Y. Zhen, R. Sadoski, S. Grinnell, L. Geren, S. Ferguson-Miller, B. Durham, and F. Millett. 1999. Definition of the interaction domain for cytochrome c on cytochrome c oxidase. J. Biol. Chem. 274:38042–38050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Szundi, I., J. A. Cappucino, N. Borovok, B. Kotlyar, and Ó. Einarsdóttir. 2001. Photoinduced electron transfer in the cytochrome c/cytochrome c oxidase complex using thiouredopyrenetrisulfonate-labeled cytochrome c. Optical multichannel detection. Biochemistry. 40:2186–2193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Farver, O., and I. Pecht. 1992. Low activation barriers characterize intramolecular electron transfer in ascorbate oxidase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 89:8283–8287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Farver, O., S. Wherland, and I. Pecht. 1994. 1994. Intramolecular electron transfer in ascorbate oxidase is enhanced in the presence of oxygen. J. Biol. Chem. 269:22933–22936. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Farver, O., L. Bendahl, L. K. Skov, and I. Pecht. 1999. Human ceruloplasmin. Intramolecular electron transfer kinetics and equilibration. J. Biol. Chem. 274:26135–26140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Suzuki, S., T. Kohzuma, A. Deligeer, K. Yamagushi, N. Nakamura, S. Shidara, K. Kobayashi, and T. Tagawa. 1994. Pulse radiolysis studies on nitrite reductase from Achromobacter cycloclastes IAM 1013: evidence for intramolecular electron transfer from type 1 Cu to type 2 Cu. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 116:11145–11446. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Farver, O., R. R. Eady, G. Sawers, M. Prudencio, and I. Pecht. 2004. Met144ala mutation of the copper-containing nitrite reductase from Alcaligenes xylosoxidans reverses the intramolecular electron transfer. FEBS Lett. 561:173–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kobayashi, K., S. Tagawa, and S. Suzuki. 1999. The pH-dependent changes of intramolecular electron transfer on copper-containing nitrite reductase. J. Biochem. (Tokyo). 126:408–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Farver, O., R. R. Eady, and I. Pecht. 2004. Reorganization energies of the individual copper centers in dissimilatory nitrite reductases. J. Phys. Chem. Ser. A. 108:9005–9007. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Suzuki, S., T. Maetani, K. Yamagushi, K. Kobayashi, and S. Tagawa. 2005. The intramolecular electron transfer between the type 1 Cu and the type 2 Cu in a mutant of Hyphomicrobium nitrite reductase. Chem. Lett. (Jpn.). 34:36–37. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kobayashi, K., A. Koppenhöfer, S. J. Ferguson, and S. Tagawa. 1997. Pulse radiolysis studies on cytochrome cd1 nitrite reductase from Thiosphaera pantotropha: evidence for a fast intramolecular electron transfer from c-heme to d1-heme. Biochemistry. 36:13611–13616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kobayashi, K., A. Koppenhöfer, S. F. Ferguson, N. J. Watmough, and S. Tagawa. 2001. Intramolecular electron transfer from c heme to d1 heme in bacterial cytochrome cd1 nitrite reductase occurs over the same distances at very different rates depending on the source of the enzyme. Biochemistry. 40:8542–8547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Farver, O., P. M. H. Kroneck, W. G. Zumft, and I. Pecht. 2002. Intramolecular electron transfer in cytochrome cd1 nitrite reductase from Pseudomonas stutzeri; kinetics and thermodynamics. Biophys. Chem. 98:27–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Farver, O., P. M. H. Kroneck, W. G. Zumft, and I. Pecht. 2003. Allosteric control of internal electron transfer in cytochrome cd1 nitrite reductase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 100:7622–7625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Anderson, R. F., R. Hille, and V. Massey. 1986. The radical chemistry of milk xanthine oxidase as studied by radiation chemistry techniques. J. Biol. Chem. 261:15870–15876. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hille, R., and R. F. Anderson. 1991. Electron transfer in milk xanthine oxidase as studied by pulse radiolysis. J. Biol. Chem. 266:5608–5615. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kobayashi, K., M. Miki, K. Okamoto, and N. Nishino. 1993. Electron transfer process in milk xanthine dehydrogenase as studied by pulse radiolysis. J. Biol. Chem. 268:24642–24646. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kobayashi, K., H. Une, and K. Hayashi. 1989. Electron transfer process in cytochrome oxidase after pulse radiolysis. J. Biol. Chem. 264:7976–7980. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Farver, O., O. Einarsdottir, and I. Pecht. 2000. Electron transfer rates and equilibrium within cytochrome c oxidase. Eur. J. Biochem. 267:950–954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Iwata, S., C. Ostermeier, B. Ludwig, and H. Michel. 1995. Structure at 2.8 Å resolution of cytochrome c oxidase from Paracoccus denitrificans. Nature. 376:660–669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tsukihara, T., H. Aoyama, E. Yamashita, T. Tomizaki, H. Yamaguchi, K. Shinzawa-Itoh, R. Nakashima, R. Yaono, and S. Yoshikawa. 1995. Structures of metal sites of oxidized bovine heart cytochrome c oxidase at 2.8 Å. Science. 269:1069–1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tsukihara, T., H. Aoyama, E. Yamashita, T. Tomizaki, H. Yamaguchi, K. Shinzawa-Itoh, R. Nakashima, R. Yaono, and S. Yoshikawa. 1996. The whole structure of the 13-subunit oxidized cytochrome c oxidase at 2.8 Å. Science. 272:1136–1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ostermeier, C., A. Harrenga, U. Ermler, and H. Michel. 1997. Structure at 2.7 Å resolution of the Paracoccus denitrificans two-subunit cytochrome c oxidase complexed with an antibody FV fragment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 94:10547–10553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yoshikawa, S., K. Shinzawa-Itoh, R. Nakashima, R. Yaono, E. Yamashita, N. Inoue, M. Yao, M. J. Fei, C. Peters-Libeu, T. Mizushima, H. Yamaguchi, T. Tomizaki, and T. Tsukihara. 1998. Redox-coupled crystal structural changes in bovine heart cytochrome c oxidase. Science. 280:1723–1729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Harrenga, A., and H. Michel. 1999. The cytochrome c oxidase from Paracoccus denitrificans does not change the metal center ligation upon reduction. J. Biol. Chem. 274:33296–33299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Soulimane, T., G. Buse, G. P. Bourenkov, H. D. Bartunik, R. Huber, and M. E. Than. 2000. Structure and mechanism of the aberrant ba3-cytochrome c oxidase from Thermus thermophilus. EMBO J. 19:1766–1776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Svensson-Ek, M., J. Abramson, G. Larsson, S. Törnroth, P. Brzezinski, and S. Iwata. 2002. The X-ray crystal structures of wild-type and EQ(I-286) mutant cytochrome c oxidases from Rhodobacter sphaeroides. J. Mol. Biol. 321:329–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hendler, R. W., K. Pardhasaradi, B. Reynafarje, and B. Ludwig. 1991. Comparison of energy-transducing capabilities of the two- and three-subunit cytochromes aa3 from Paracoccus denitrificans and the 13-subunit beef heart enzyme. Biophys. J. 60:415–423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hellwig, P., S. Grzybek, J. Behr, B. Ludwig, H. Michel, and W. Mäntele. 1999. Electrochemical and ultraviolet/visible/infrared spectroscopic analysis of heme a and a3 redox reactions in the cytochrome c oxidase from Paracoccus denitrificans: separation of heme a and a3 contributions and assignment of vibrational modes. Biochemistry. 38:1685–1694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pan, L. P., S. Hibdon, R.-Q. Liu, B. Durham, and F. Millett. 1993. Intracomplex electron transfer between ruthenium-cytochrome c derivatives and cytochrome c oxidase. Biochemistry. 32:8492–8498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Richter, O.-M. H., K. L. Dürr, A. Kannt, B. Ludwig, F. M. Scandurra, A. Giuffrèe, P. Sarti, and P. Hellwig. 2005. Probing the access of protons to the K pathway in the Paracoccus denitrificans cytochrome c oxidase. FEBS J. 272:404–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Verkhovsky, M. I., J. E. Morgan, and M. Wikström. 1995. Control of electron delivery to the oxygen reduction site of cytochrome c oxidase: a role of protons. Biochemistry. 34:7483–7491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wikström, M., M. I. Verkhovsky, and G. Hummer. 2003. Water-gated mechanism of proton translocation by cytochrome c oxidase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1604:61–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Marcus, R. A., and N. Sutin. 1985. Electron transfers in chemistry and biology. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 811:265–322. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Beratan, D. N., J. N. Onuchic, J. R. Winkler, and H. B. Gray. 1992. Electron-tunneling pathways in proteins. Science. 258:1740–1741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kurnikov, I. V., and D. N. Beratan. 1996. Ab initio based effective Hamiltonians for long-range electron transfer: Hartree-Fock analysis. J. Chem. Phys. 105:9561–9573. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Brzezinski, P. 1996. Internal electron-transfer reactions in cytochrome c oxidase. Biochemistry. 35:5611–5615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ramirez, B. E., B. G. Malmström, J. R. Winkler, and H. B. Gray. 1995. The currents of life: the terminal electron-transfer complex of respiration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 92:11949–11951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]