Abstract

The rho-type GTPase Cdc42 is important for the establishment and maintenance of eukaryotic cell polarity. To examine whether Cdc42 is regulated during the yeast-to-hypha transition in Candida albicans, we constructed a green fluorescence protein (GFP)-Cdc42 fusion under the ACT1 promoter and observed its localization in live C. albicans cells. As in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, GFP-Cdc42 was observed around the entire periphery of the cell. In yeast-form cells of C. albicans, it clustered to the tips and sides of small buds as well as to the mother-daughter neck region of large-budded cells. Upon hyphal induction, GFP-Cdc42 clustered to the site of hyphal evagination and remained at the tips of the hyphae. This temporal and spatial localization of Cdc42 suggests that its activity is regulated during the yeast-to-hypha transition. In addition to the accumulation at the hyphal tip, GFP-Cdc42 was also seen as a band within the hyphal tube in cells that had undergone nuclear separation. With the F-actin-assembly inhibitor latrunculin A, we found that GFP-Cdc42 accumulation at the bud site in yeast-form cells is F-actin independent, whereas GFP-Cdc42 accumulation at the hyphal tip requires F-actin. Furthermore, disruption of the F-actin cytoskeleton impaired the transcriptional induction of hypha-specific genes. Therefore, hypha formation resembles mating in Saccharomyces cerevisiae in that both require F-actin for GFP-Cdc42 localization and efficient signaling.

Polarized cell growth is important in all aspects of cellular development in both unicellular and multicellular organisms. Such growth requires the selection of a specific site, followed by rearrangement of the actin cytoskeleton to the site. A major regulator in these types of actin cytoskeletal rearrangements is the rho-type GTPase Cdc42, whose function and regulation have been studied extensively in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Cdc42 is essential for budding, mating (1, 29), and pseudohyphal growth (19). Cdc42's subcellular localization correlates with its activity and is essential for its function.

During budding, green fluorescent protein (GFP)-Cdc42 clusters to the incipient bud site (22, 29), marked by the Bud1 GTPase module (6, 21), and later to the tips and sides of growing buds, until they reach medium size, at which point GFP-Cdc42 starts to diffuse. In large-budded cells postanaphase, GFP-Cdc42 clusters as a band at the mother-daughter neck region and persists as two distinct bands on mother-daughter cells following cytokinesis and cell separation (22). In S. cerevisiae, GFP-Cdc42 is also found at the plasma membrane of the entire periphery of the cell and on internal membranes. C-terminal CAAX and polylysine domains are sufficient for membrane targeting but not for clustering (22). During mating, Cdc42 is recruited to the tips of mating projections (shmoos) (29), possibly through the action of the pheromone receptor via Far1 and Cdc24 (12). In both cases, the activated Cdc42, in turn, activates downstream effectors that signal to the actin cytoskeleton. Studies done in S. cerevisiae with latrunculin A, a drug known to bind monomeric actin and therefore disassemble filamentous actin (F-actin) (8), have shown that Cdc42 accumulation at the prebud site is F-actin independent, whereas Cdc42 accumulation to the shmoo tip during mating is F-actin dependent (4, 5).

Candida albicans is a dimorphic fungus that can undergo reversible morphogenetic transitions between yeast and hyphal forms, and the ability to switch between these morphologies is linked to its pathogenesis (15). Hyphal elongation is an extreme example of polarized growth. The actin cytoskeleton is polarized to the tip of the hyphae (3) and is required for hyphal elongation (28). A C. albicans CDC42 gene has been cloned, and it encodes a protein with a high degree of identity to S. cerevisiae Cdc42 (87.8%) and human Cdc42 (76.4%) (18). Functional analysis of cdc42 mutants of C. albicans suggested that Cdc42 is important for budding as well as polarized growth in hyphae (26).

Our previous studies suggested that polarized growth in response to hyphal induction in C. albicans is not mediated by altering the progression of the cell cycle (13), in contrast to pseudohyphal elongation in S. cerevisiae (14). Rather, hypha-associated polarization of the actin cytoskeleton at the hyphal tip is regulated independently of the cell cycle. We further postulated that the hypha-associated morphogenesis program and the cell cycle program converge to regulate a common signaling module (13), presumably Cdc42, which in turn controls the polarization of the actin cytoskeleton. In this report we show that Cdc42 is regulated, as reflected by its localization, by both the hyphal morphogenesis program and the cell cycle. We further demonstrate that GFP-Cdc42 accumulation at the tip of polarized growth during hyphal induction resembles mating in S. cerevisiae in that both rely on an intact actin cytoskeleton.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmid and strain construction.

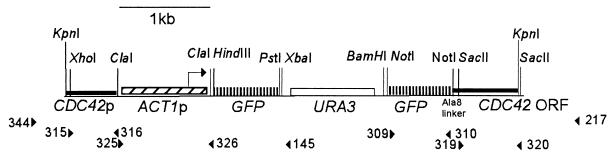

To construct a fusion of GFP to the N terminus of Cdc42 in C. albicans, we started with plasmid pHL471, which contains GFP and URA3 on a pBluescript SK (13). A second copy of GFP was generated by PCR from plasmid pHL471 with primers 309 and 310 and cloned into the NotI site in pHL471 to give pHL584. The second GFP lacks the sequence for the first 8 amino acids and the stop codon but contains an Ala8 linker at the C terminus. We next generated two different GFP-Cdc42 fusions, one under its endogenous promoter and the other under the C. albicans ACT1 (CaACT1) promoter. A 500-bp PCR fragment from the CDC42 promoter region (with primers 315 and 316) was cloned into the XhoI and ClaI sites in pHL584 to give pHL585. Then, for the CaACT1-regulated GFP-Cdc42, a 1,000-bp PCR fragment from the region upstream of CaACT1 (with primers 325 and 326) was cloned into the ClaI site of pHL585 to give pHL593. Next, a 500-bp PCR fragment from the CDC42 coding region immediately downstream of the start codon (with primers 319 and 320) was cloned in frame to the Ala8 linker into the SacII site of pHL593 and pHL585, resulting in pHL598 (with the CaACT1 promoter) and pHL587 (with the endogenous promoter). A KpnI site was engineered into the C-terminal end of the 500-bp CDC42 PCR fragment. Sequence of all cloned fragments in pHL598 and pHL587 were confirmed by DNA sequencing. The final plasmids, pHL598 and pHL587, were digested with KpnI to release the linear CDC42p-ACT1p-GFP-URA3-GFP-CDC42 fragment or CDC42p-GFP-URA3-GFP-CDC42 from pBluescript for C. albicans transformation (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

GFP-CDC42 fusion construct. The region of plasmid pHL598 used for C. albicans transformation is shown. The position and direction of primers used for PCR are indicated. Primers 217 and 344 are located outside of the CDC42 genomic region used in the construct. The second GFP is in frame with an Ala8 linker and CDC42. URA3 and one copy of GFP are excised by selecting for homologous recombination on 5-fluoroorotic acid.

CAI4 was transformed with KpnI-digested pHL598 and pHL587, and Ura+ transformants with integration at the CDC42 locus were detected by PCR with primer pairs 309 and 217, 344 and 310, and 344 and 145 (data not shown). Recombination between two GFP copies in the transformants was selected on 5-fluoroorotic acid-containing medium and confirmed by PCR with primer pairs 309 and 217 and 344 and 310 (data not shown). Strains carrying proper GFP fusions were observed under a microscope. The fluorescence from GFP-Cdc42 under the endogenous promoter (HLY3230) was fainter and harder to capture as images than that under the CaACT1 promoter.

Our subsequent work was carried out with GFP-Cdc42 under the CaACT1 promoter. The Ura− ACT1p-GFP-CDC42 strain (HLY3226; Δura3::imm434/Δura3::imm434 CDC42/ACT1p-GFP-CDC42) was rendered Ura+ by transforming with AscI-digested BES116 (9), which integrates URA3 into the ADE2 locus. One resulting Ura+ ACT1p-GFP-CDC42 strain, HLY3227 (Δura3::imm434/Δura3::imm434 CDC42/ACT1p-GFP-CDC42 ADE2/ade2::URA3), was used for this study. Strain HLY3227 had the same growth rate as the wild-type strain SC5314. A Northern analysis of strains SC5314 and HLY3227 probed with CDC42 suggested that expression from the CaACT1 promoter is about twice that of the endogenous promoter. The sequences of the primers used in this strain construction are shown in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Primers used in this study

| Primer | Sequence |

|---|---|

| 145 | 5′-ATA CCA TCC AAA TCA ATT CC-3′ |

| 217 | 5′-AAA CAG CCC AAC ACA TCA AAC G-3′ |

| 309 | 5′-ATA AGA ATG CGG CCG CAC TGG TGT TGT CCC AAT TTT GGT TG-3′ |

| 310 | 5′-ATA GTT TAG CGG CCG CGG CAG CAG CAG CGG CAG CGG CAG CTT TGT ACA ATT CAT CCA TAC CAT GG-3′ |

| 315 | 5′-CCG CTC GAC CGG CTG AGA GTG ATA GAT ATC TTA GC-3′ |

| 316 | 5′-CCA TCG ATG GGA TAT ATG GAT ATA TTA ATT ATT TAT GAG C-3′ |

| 319 | 5′-TCC CCG CGG TGC AAA CTA TAA AAT GTG TTG TTG TC-3′ |

| 320 | 5′-TCC CCG CGG CGT CAA ACA CTG TTT TCA ATC C-3′ |

| 325 | 5′-CCA TCG ATC TAT TAA GAT CAC CAG CCT CG-3′ |

| 326 | 5′-CCA TCG ATT TTG AAT GAT TAT ATT TTT TTA ATA T-3′ |

| 344 | 5′-AAT CTT CCA AGC GTC CTT ACC-3′ |

In order to test the functionality of the ACT1p-GFP-CDC42 construct, we set out to delete the remaining wild-type copy of CDC42. This was done by transforming strain HLY3226 with KpnI-digested pHL598 (CDC42p-ACT1p-GFP-URA3-GFP-CDC42). This DNA fragment constitutes a disruption of CDC42. Only after 5-fluoroorotic acid treatment and recombination between the two tandem GFPs does the GFP become fused in-frame with CDC42. Positive (Ura+) transformants were screened by PCR with primers 315 and 320, 344 and 310, and 344 and 145 (data not shown). Surprisingly, all the transformants still had a wild-type copy of CDC42. Among the transformants that had the transforming DNA integrated at the CDC42 locus, 50% had replaced the previous GFP-CDC42 with GFP-URA3-GFP-CDC42, and in the other 50% GFP-URA3-GFP-CDC42 replaced a wild-type copy (as shown by the existence of three different PCR fragments: wild-type CDC42, GFP-CDC42, and GFP-URA3-GFP-CDC42). If ACT1p-GFP-CDC42 is not functional, we would have expected the integration to replace the existing GFP-CDC42 only. Because 50% of integrations at CDC42 went into a wild-type CDC42, we theorized that there might be three copies of CDC42 in our strain. To delete the third copy of CDC42, we first needed to generate a Ura− strain with two copies of GFP-CDC42. We selected Ura− colonies from the second round of transformation on 5-fluoroorotic acid and then screened the Ura− strains by fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis (7) for strains that had a twofold fluorescence in the fluorescein isothiocyanate channel (in comparison to the original GFP-Cdc42 strain HLY3227). The strains with twofold fluorescence were transformed a third time with KpnI-digested pHL598 (CDC42p-ACT1p-GFP-URA3-GFP-CDC42). By PCR with primers 315 and 320, 344 and 310, and 344 and 145 (data not shown), we were able to identify a strain that had two copies of ACT1p-GFP-CDC42 and one copy of ACT1p-GFP-URA3-GFP-CDC42 and no wild-type CDC42. This strain was viable and grew normally. HLY1541, a β-tubulin-GFP strain, was also used in this study (13).

Growth of C. albicans strains.

C. albicans was cultured essentially as described for S. cerevisiae (23). Cells were grown in YPD medium at 30°C, then either elutriated or diluted directly into YPD or SC at 30°C for yeast-form growth and YPD or SC with 10% newborn calf serum (Sigma) at 37°C for hyphal growth. Visualization of GFP-Cdc42 had less background in SC medium. In experiments where latrunculin A was used, all samples were cultured in small volumes (75 to 500 μl) due to the cost of the reagent. Yeast-form cells were grown in 2-ml glass vials on a wheel at 25°C, and hyphal cells were grown in 1.8-ml plastic microcentrifuge tubes at 37°C in a shaking water bath.

Cell synchronization.

Cell synchronization was performed as previously described (16). Unbudded G1 cells were released into YPD or SC at 30°C for yeast-form growth and YPD or SC with 10% serum at 37°C for hyphal growth, and aliquots of cells were taken for direct visualization by microscopy.

Latrunculin A treatment.

Latrunculin A (Molecular Probes) was added directly to media from a 20 mM stock in dimethyl sulfoxide to a final concentration of 200 μM or 800 μM. In experiments where cells were treated with latrunculin A for longer than 3 h at 37°C, additional latrunculin A (one third of the initial amount) was added after 3 h.

Halo assays.

An S. cerevisiae wild-type diploid strain and the C. albicans β-tubulin-GFP strain (HLY1541) were grown overnight in YPD. The C. albicans overnight culture was diluted to the same optical density as the S. cerevisiae overnight culture. Then 10-μl aliquots of the normalized overnight cultures were added to 2 ml of 2× YPD, mixed with 2 ml of 1% top agar (cooled to 55°C), and poured over YPD plates, and 10-μl aliquots of latrunculin A in different concentrations (0, 0.5, 1.0, 2.0, 4.0, 8.0, and 16.0 mM) were prepared by diluting 20 mM latrunculin A stock into water and pipetted onto the center of a sterile 7-mm disk placed on the YPD plate. The plates were incubated at 30°C for 24 h.

Microscopy.

A Zeiss Axioplan2 microscope with a 100× objective and a digital camera (Sensys Photometrics) was used for all microscopy. Visualization of GFP-Cdc42 (HLY3227) and β-tubulin-GFP (HLY1541) was performed as described by Hazan et al. (13).

To visualize DNA in live C. albicans cells, cultures were grown in the presence of 1 μg of 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) per ml for at least 16 h (40 h gave better results), then diluted into a fresh medium containing 1 μg of DAPI per ml and photographed directly in the medium. Rhodamine-phalloidin staining of F-actin was performed based on the protocol described (2) and modified as described by Hazan et al. (13). Calcofluor staining was done as described in Hazan et al. (13).

Northern blotting.

GFP-Cdc42 cells were diluted from an overnight culture into YPD medium at 30°C for yeast-form growth and YPD with 10% serum at 37°C for hyphal growth with or without 200 μM latrunculin A for 3.5 h. Cells were harvested and frozen in liquid nitrogen, and acid-phenol RNA extraction was performed (11). DNA probes were labeled with the Stratagene Prime-It II random priming kit and [α-32P]dCTP (Invitrogen). Probes for CaHWP1, CaECE1, and CaHYR1 were made as described by Loeb et al. (16). The sizes of mRNAs on our Northern blots correlated with the expected lengths of these genes. Blots were exposed and quantitated with the Personal Molecular Imager FX (Bio-Rad) and Quantity One software, version 4.2.1 (Bio-Rad).

RESULTS

Localization of GFP-Cdc42 in C. albicans.

Cdc42 localization is known to correlate with its activity and function in many organisms. To elucidate the function of Cdc42 and its regulation in C. albicans, we constructed GFP fusions to the N terminus of Cdc42 both under its own promoter and under the CaACT1 promoter (Fig. 1). The level of GFP-CDC42 transcript from the CaACT1 promoter was about twice that from the CDC42 promoter by Northern analysis (data not shown). Both fusions gave similar Cdc42 localization, but GFP-Cdc42 under the endogenous promoter was fainter than that of the CaACT1 promoter. Therefore, the strain carrying GFP-Cdc42 under the CaACT1p (HLY3227) was used for the rest of the studies. This GFP-Cdc42 fusion is functional in C. albicans, because we were able to disrupt other wild-type copies of CDC42 and obtain a viable strain in which GFP-Cdc42 was the sole source of Cdc42 (see Materials and Methods).

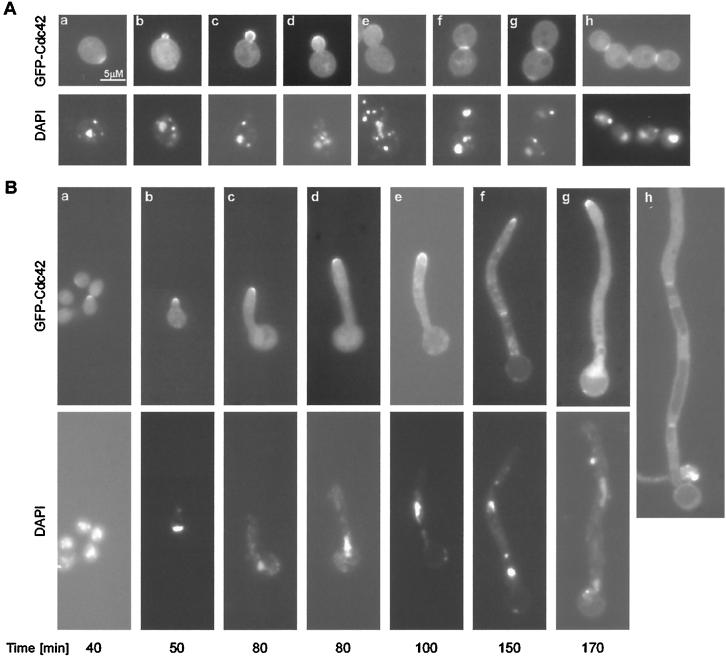

In log-phase growing yeast-form cells, GFP-Cdc42 localization was very similar to the reported localization in S. cerevisiae (22). Localization at the entire cell periphery was observed in both unbudded and budded cells. GFP-Cdc42 clustered to a discrete spot at the plasma membrane on emerging buds (Fig. 2Ab). This localization was also seen on the tips and sides of growing buds (Fig. 2Ac and -d) but was not seen in large-budded cells (Fig. 2Ae). A band of GFP-Cdc42 was observed at the mother-daughter neck region in large-budded cells post nuclear separation (Fig. 2Af and -g). In S. cerevisiae, double bands of GFP-Cdc42 were observed at the neck of mother-daughter cells post cytokinesis in cells grown on solid medium (22). We observed a similar faint double band at the mother and daughter neck region, which still existed in cells at the end of the second cell cycle, as shown in Fig. 2Ah. The persistence of this localization may explain the faint GFP-Cdc42 patch visible in many unbudded cells and in budded cells at a site opposite to the side of the bud (Fig. 2Aa, 2Ab, 2Ae, and 2Ag). GFP-Cdc42 localization was also visible on internal membranes in many cells, possibly on vacuoles (Fig. 2Ac, 2Ad, 2Af, and 2Ag), as has been reported for Schizosaccharomyces pombe (17) and S. cerevisiae (22).

FIG. 2.

GFP-Cdc42 localization in yeast-form and hyphal cells. (A) Yeast-form cells from a log-phase culture of the GFP-Cdc42 strain (HLY3227) grown in SC medium in the presence of 1 μg of DAPI per ml were photographed under a fluorescence microscope. GFP-Cdc42 localization (upper panel) and the corresponding DAPI images (lower panel) are shown. (B) A 40-h culture of the GFP-Cdc42 strain (HLY3227) grown in the presence of 1 μg of DAPI per ml in YPD at 30°C was diluted into SC with 10% serum with 1 μg of DAPI per ml at 37°C for hyphal induction. Aliquots were taken and observed under a fluorescence microscope every 10 min. The GFP-Cdc42 localization (upper panel) and DAPI images (lower panel) of representative cells from indicated time points are shown.

When two overnight cultures (approximately 97% of the cells were unbudded) were exposed to hyphal induction in 10% serum, GFP-Cdc42 clustered at the tips of emerging germ tubes at about 40 min (Fig. 2Ba). No nuclear migration was observed in these cells. All cells observed after 40 min had GFP-Cdc42 accumulation at the hyphal tip, indicating that GFP-Cdc42 clustering persisted at the hyphal tip (Fig. 2Ba to Bg). GFP-Cdc42 in the shape of a band appeared in the hyphal tube at approximately 150 min after hyphal induction and these cells had separated nuclei (Fig. 2Bf). The band was not seen in cells from later time points, but a fainter double band was observed instead (Fig. 2Bg). This faint double-band seemed to persist to the next cell cycle (Fig. 2Bh).

In order to determine the timing of GFP-Cdc42 localization to the hyphal tip in the events of the cell cycle, synchronous G1 cells were released into hyphal medium. GFP-Cdc42 localization at the tip coincided with germ tube emergence and appeared at approximately 30 min, which was 70 min prior to DNA replication, as analyzed by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (data not shown). In yeast-form cells, DNA replication, budding, and spindle pole body duplication all initiate at the G1/S transition, and the timing of DNA replication, spindle pole body duplication is the same between yeast and hyphal cells when synchronous G1 cells are transferred to yeast growth and hypha-inducing medium (13). The facts that GFP-Cdc42 localization to the tip of hyphae occurred 70 min before the other G1/S transition events and persisted at the tip throughout the cell cycle suggest that GFP-Cdc42 localization to the hyphal tip is regulated by a cell cycle-independent morphogenesis program that is activated upon hyphal induction in serum. Thus, like actin localization, two types of GFP-Cdc42 localization, periodic, cell cycle-associated localization in the shape of a band postanaphase and constitutive association with the growing hyphal tip coexist in hyphal cells.

Effect of latrunculin A on actin cytoskeleton and cell cycle progression in C. albicans.

In S. cerevisiae, GFP-Cdc42 localization during budding is F-actin independent, while its polarization during mating requires the actin cytoskeleton as shown by treatment of yeast cells with latrunculin A, a drug that causes a complete disassembly of F-actin within 2 min (4, 5). Latrunculin A acts on S. cerevisiae specifically through actin depolymerization because three act1 point mutants are resistant to latrunculin A treatment (5).

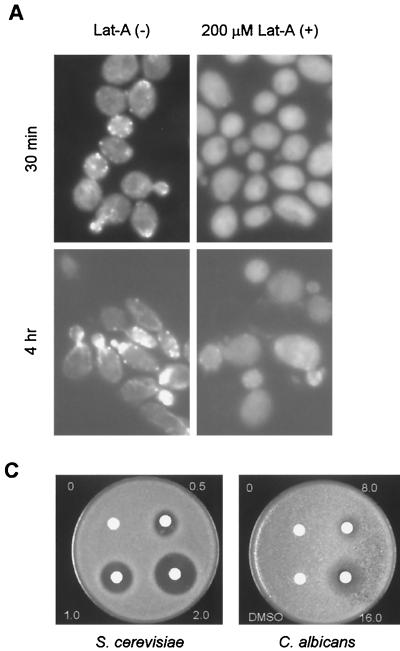

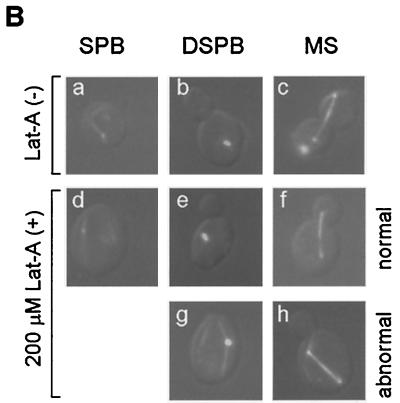

To investigate if the actin cytoskeleton is required for GFP-Cdc42 localization during hyphal growth in C. albicans, we first examined the effect of latrunculin A on the actin cytoskeleton in C. albicans. No F-actin structures were detected by rhodamine-phalloidin staining in cells in 200 μM latrunculin A for 30 min or 4 h (Fig. 3A), indicating that latrunculin A caused a disruption of F-actin in C. albicans. Although budding in diploid wild-type cells of S. cerevisiae is mostly inhibited by 100 μM latrunculin A (5), the majority of C. albicans cells were able to bud in the presence of 200 μM latrunculin A (data not shown). At this concentration, latrunculin A only partially affected budding (Fig. 3B); 25.1 ± 9.8% of cells with duplicated spindle pole body cells were unbudded (Fig. 3Bg). In addition, 26.5 ± 9.4% of mitotic spindles were misoriented in latrunculin A-treated cells (Fig. 3Bh), likely due to the disruption of the actin cytoskeleton, which is known to be important for guiding astral microtubules into the bud in S. cerevisiae (25). It is likely that 200 μM latrunculin A does not completely depolymerize F-actin. The residual amount of F-actin was not detectable by rhodamine-phalloidin staining, but was sufficient to allow budding to happen. Consistent with this, C. albicans cells were unable to bud in the presence of 800 μM latrunculin A (Fig. 4A). Therefore, budding is F-actin dependant in C. albicans, but C. albicans is more resistant to latrunculin A in liquid medium than S. cerevisiae.

FIG. 3.

Effect of latrunculin A on C. albicans. (A) Log-phase cultures of the GFP-Cdc42 strain HLY322 were incubated in YPD medium at 30°C in the presence and absence of 200 μM latrunculin A (Lat-A). Cells were fixed and stained with rhodamine-phalloidin at 30 min and 4 h after addition of latrunculin A. (B) Appearance of spindle structures (spindle pole body [SPB], duplicated spindle pole body [DSPB], and mitotic spindles [MS]) in latrunculin A-treated and untreated cells. Synchronous G1 cells of β-tubulin-GFP were transferred to YPD medium at 30°C in the presence and absence of latrunculin A. Tubulin-GFP and differential interference contrast images were photographed and merged. Abnormal appearance of duplicated spindle pole bodies in unbudded cells (g) and misoriented mitotic spindles (h) in latrunculin A-treated cells compared to normal spindle structures in untreated (a to c) and treated (d to f) cells are shown. (C) Growth inhibition of S. cerevisiae and C. albicans by latrunculin A shown by halo assays. We used 10 μl of different latrunculin A stocks, as indicated (in millimolar).

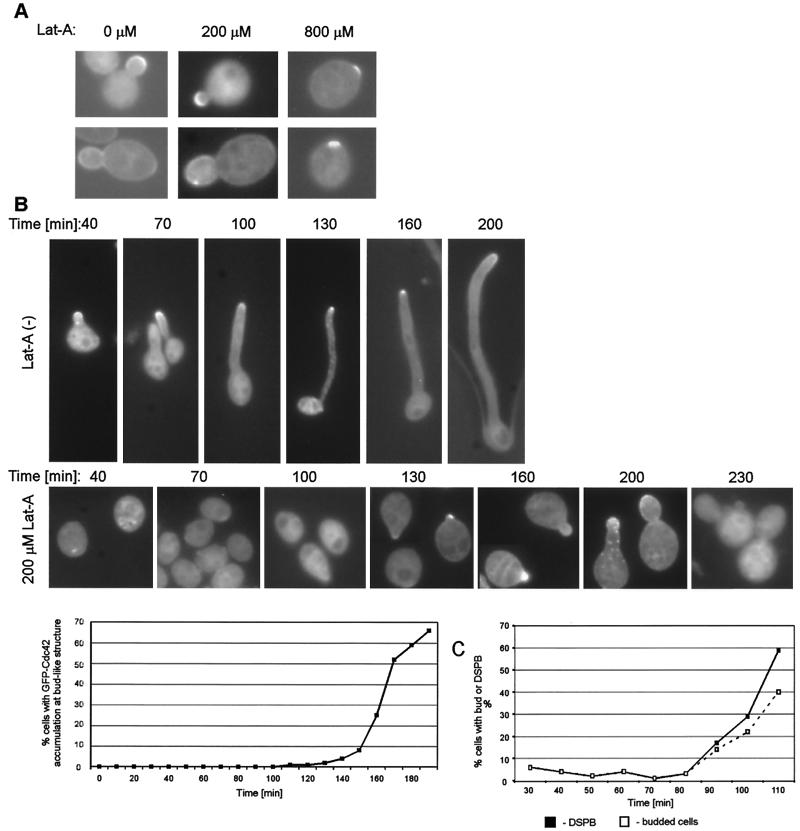

FIG. 4.

Effect of latrunculin A on budding and on hyphal tip-associated GFP-Cdc42 localization. (A) Synchronous G1 cells of the GFP-Cdc42 strain (HLY3227) were released into SC medium at 30°C in the absence and presence of 200 μM and 800 μM latrunculin A (Lat-A). Photographs were taken approximately 2 h after addition of latrunculin A for the 0 and 200 μM concentrations and at 2.5 to 3 h for the 800 μM concentration. (B) Synchronous G1 cells of the GFP-Cdc42 strain (HLY3227) were transferred to SC with 10% serum at 37°C in the absence (upper panel) and presence (lower panel) of 200 μM latrunculin A. GFP-Cdc42 images were taken at the times indicated. Another dose (one third of the initial dose) of latrunculin A was added at 3.5 h of incubation. Cells from several time points were stained with rhodamine-phalloidin to ensure that no actin polarization was detectable. The percentage of cells with GFP-Cdc42 clustering on bud-like structures is plotted against time. (C) Synchronous G1 cells of the β-tubulin-GFP strain (HLY1541) were transferred into YPD with 10% serum at 37°C in the presence of latrunculin A. The percentages of cells with duplicated spindle pole bodies and of cells with the bud-like structures were determined every 10 min.

We also tested the growth inhibition of C. albicans by latrunculin A on solid media. Disks containing various concentrations of latrunculin A were placed on a lawn of cells (Fig. 3C). The latrunculin A concentration required to inhibit S. cerevisiae growth was similar to that reported previously (5). Similar concentrations of latrunculin A had no effect on C. albicans (data not shown). Nevertheless, halos were observed in the disks containing 10 μl of 8.0 and 16.0 mM latrunculin A (Fig. 3C, right panel). Therefore, much higher concentrations of latrunculin A were required to arrest growth in C. albicans.

Effect of latrunculin A on GFP-Cdc42 localization during budding and hyphal formation.

We first examined whether F-actin was required for GFP-Cdc42 localization in yeast-form cells. Elutriated G1 cells of the GFP-Cdc42 strain (HLY3227) were transferred into yeast growth medium with and without latrunculin A. No GFP-Cdc42 patches or clusters were observed in the starting cells. In the presence of 200 μM latrunculin A, GFP-Cdc42 accumulation on the buds appeared at approximately 2 h (Fig. 4A). In the presence of 800 μM latrunculin A, cells were unable to bud, but a discrete cluster of GFP-Cdc42 was observed in unbudded cells after approximately 2.5 to 3 h of growth (Fig. 4A).

We believe that this GFP-Cdc42 clustering is not a remnant from a previous cell cycle but represents accumulation at the presumptive bud site, because it was not observed in these cells at earlier time points. Therefore, GFP-Cdc42 accumulation to the prebud site is not dependent on F-actin in C. albicans, as reported for S. cerevisiae (5). GFP-Cdc42 localization as a band at the mother-daughter neck was rarely seen in latrunculin A (200 μM and 800 μM)-treated cells, either because this event was out of the time frame of the experiment or because latrunculin A caused a cell cycle delay in late mitosis which affected the postanaphase GFP-Cdc42 localization.

To determine whether F-actin is required for hyphal tip-associated GFP-Cdc42 localization, synchronous G1 GFP-Cdc42 (HLY3227) cells were put into hypha-inducing medium (SC with 10% serum at 37°C) in the absence and presence of 200 μM latrunculin A. At approximately 40 min, germ tube formation and GFP-Cdc42 clustering at the tip started to appear in the absence of latrunculin A (Fig. 4B, upper panel). Cells were longer in the later time points, and they all had GFP-Cdc42 accumulation at the tip. In contrast, in the presence of 200 μM latrunculin A, cells showed no GFP-Cdc42 clustering during the initial stage of hyphal induction and remained in their round shape with no buds or germ tubes (Fig. 4B, middle panel). Therefore, the hyphal tip-associated GFP-Cdc42 localization is F-actin dependent. It is clear that hypha-associated polarized growth is much more sensitive to latrunculin A treatment than budding, since it required 800 μM latrunculin A to block budding. It is possible that cells need more F-actin to form polarized hyphae than they need to form a bud.

At approximately 130 min, discrete GFP-Cdc42 clusters were observed in what appeared to be small buds or germ tube evaginations (Fig. 4B, middle panels, 130 min). These “buds” appeared larger at later time points (Fig. 4B, middle panel, 160 and 200 min), and the discrete GFP-Cdc42 localization was more dispersed in large buds (Fig. 4B, middle panel, 230 min). The formation of the bud-like morphology was not due to a decrease in the effectiveness of latrunculin A, because rhodamine-phalloidin staining at several time points did not detect reformation of the actin cytoskeleton. On the other hand, bud formation in this experiment is possible because 200 μM latrunculin A was sufficient to inhibit hyphal formation but not bud formation.

Three pieces of evidence suggested that the bud-like morphology was indeed a bud but not a hyphal evagination. First, when these cells were fixed and stained with Calcofluor, the cells had chitin rings at the base of the bud-like structure (data not shown). Chitin rings typically appear at mother-bud necks but not at the base of hyphae. Second, the timing of their appearance in the cell cycle coincided with spindle pole body duplication. When synchronous G1 cells of the β-tubulin-GFP strain (HLY1541) were released into hypha-inducing conditions in the presence of 200 μM latrunculin A, they were not able to form hyphae but made similar bud-like structures at approximately 90 min. This coincided with the appearance of duplicated spindle pole bodies (Fig. 4C). Budding occurred earlier in this experiment than in the experiment in Fig. 4B because cells were released into YPD (instead of SC). Third, in a similar experiment in which hyphae were induced from synchronous G1 cells in the presence of 200 μM latrunculin A, hydroxyurea inhibited the bud-like structures from growing larger and arrested cells with duplicated spindle pole bodies, whereas in the absence of hydroxyurea, cells continued to enlarge their buds and progressed through the cell cycle (data not shown). Therefore, the discrete GFP-Cdc42 accumulation appearing at 130 min in the presence of latrunculin A reflected cell cycle-associated GFP-Cdc42 polarization at the site of budding rather than hyphal tip-associated GFP-Cdc42 localization.

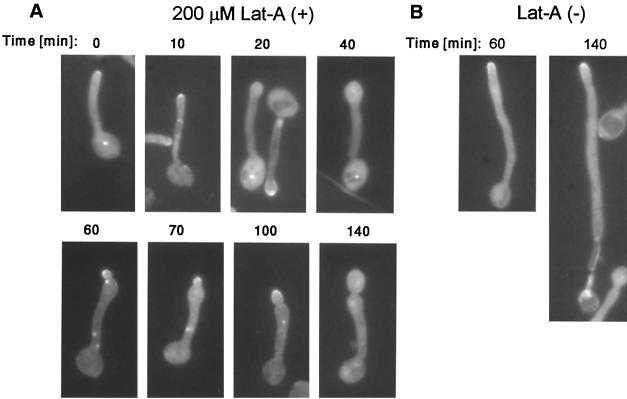

To test the effect of latrunculin A on the maintenance of GFP-Cdc42 localization at the tip of hyphae, saturated cultures were first transferred into hypha-inducing medium for 80 min, and latrunculin A was then added to the hyphal cells to a final concentration of 200 μM. Clustering of GFP-Cdc42 at the tip was apparent in all hyphal cells in the starting culture (Fig. 5A, time zero). After 10 to 20 min of latrunculin A treatment, the GFP-Cdc42 tip polarization was not apparent anymore in many cells, and hyphal tips appeared swollen, indicating a switch from apical to isotropic growth (Fig. 5A, 20 min). At later time points, cells did not appear to have longer hyphae (in comparison to latrunculin A-free cultures), but had larger swollen tips (Fig. 5A, 40 min). At approximately 50 to 60 min, we observed GFP-Cdc42 clustering at the tip and side of buds evaginated from the end of these swollen enlargements (Fig. 5A, 60 min). When these cells were fixed and stained with Calcofluor, a chitin ring was apparent at the base of the bud-like structure (data not shown), supporting the notion that these were indeed buds evaginating off swollen hyphae. GFP-Cdc42 accumulation was no longer visible in cells with very large buds (Fig. 5A, 140 min), same as budding in yeast growth.

FIG. 5.

Effect of latrunculin A on sustained hypha-associated GFP-Cdc42 polarization. Saturated cultures of the GFP-Cdc42 strain were diluted into SC with 10% serum and grown at 37°C for 80 min, after which 200 μM latrunculin A (Lat-A) was either added (A) or not (B). Times indicated are incubation time in the presence of latrunculin A.

Based on the existence of a chitin ring at their bases, the cell morphology, and the timing of GFP-Cdc42 accumulation (130 to 140 min after the original release), we believe this was cell cycle-associated GFP-Cdc42 localization at the presumptive bud site, same as seen in Fig. 4B (130 to 200 min). In the control experiment, untreated hyphal cells all had constitutive GFP-Cdc42 localization at the tips of hyphae and had progressively longer hyphae at later time points (Fig. 5B). Therefore, sustained GFP-Cdc42 accumulation at the hyphal tip is also F-actin dependent.

Role of actin cytoskeleton in transcriptional induction of hypha-specific genes.

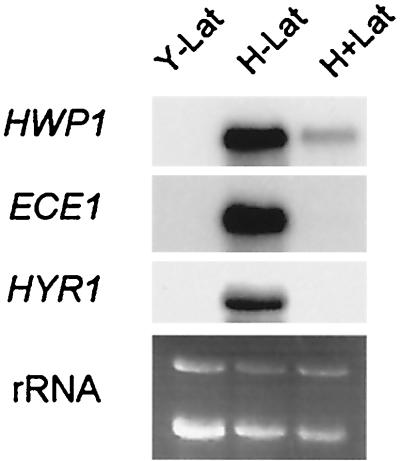

Proper localization of the signaling machinery is often important for efficient signaling. In S. cerevisiae, latrunculin A causes a 60 to 70% reduction in pheromone-induced FUS1 transcription (an output of the pheromone-responsive mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway) compared to pheromone induction in the absence of latrunculin A (4). To examine whether the actin cytoskeleton is important for the hyphal transcriptional program, we examined the induction level of three hypha-specific genes (HWP1, ECE1, and HYR1) in cells grown in hypha-inducing medium in the absence and presence of 200 μM latrunculin A.

Northern blotting showed that the transcription level of these genes was undetectable in yeast-form cells and very high in hypha-form cells (Fig. 6). In latrunculin A-treated cells, HWP1 transcription was partially induced (roughly a sixth of that of the hypha-form cells without latrunculin A). Transcription of ECE1 and HYR1 in cells treated with latrunculin A was similar to that of yeast-form cells. Thus, transcriptional induction of hypha-specific genes is affected by the disruption of the F-actin cytoskeleton. The requirement of the actin cytoskeleton in the induction of developmental genes in both hyphal induction of C. albicans and mating of S. cerevisiae indicates that the two developmental processes may have similar signaling mechanisms.

FIG. 6.

Effect of latrunculin A on transcriptional induction of hypha-specific genes. Northern blotting of cells grown in yeast medium (Y − Lat), hypha-inducing medium (H − Lat), and hypha-inducing medium with 200 μM latrunculin A (H + Lat) was probed with hypha-specific genes HWP1, ECE1, and HYR1. rRNA was used as a loading control.

DISCUSSION

C. albicans Cdc42 is involved both in the cell cycle and in hyphal morphogenesis (26). In support of this, we show that GFP-Cdc42 is clustered to the tips and sides of buds and to a band at the mother-daughter neck region in yeast-form cells. In hyphal cells, both constant accumulation of GFP-Cdc42 to the tip of growing hyphae and cyclic localization as a band in postanaphase germ tubes are observed. This is consistent with our previous observation that the rearrangement of the actin cytoskeleton in hyphal cells is regulated by the cell cycle and hypha-associated polarized growth programs in parallel. Since Cdc42 is known to be a key regulator for the rearrangement of the actin cytoskeleton in eukaryotes, its localization in C. albicans suggests that both cell cycle and hypha-associated polarized growth programs converge on Cdc42 to regulate the rearrangement of the actin cytoskeleton.

Interestingly, while cell cycle-associated GFP-Cdc42 localization is independent of the actin cytoskeleton, hypha-associated GFP-Cdc42 localization at the tip requires an intact actin cytoskeleton. Similar results have been shown for the localization of Cdc42, Cdc24, and other polarity establishment proteins during budding and shmoo formation in S. cerevisiae (4, 5). The difference in F-actin dependence between budding and mating is probably because mating projection formation requires persistent positioning of growth polarity proteins at the growth site by the activated pheromone receptor, whereas a single point localization of the polarity proteins by the Bud1 GTPase module is sufficient for bud site selection (20). F-actin is required to constrain or transport the pheromone receptors to a discrete site at the cell cortex during mating (4). The clustering of the receptors to a discrete site by actin is thought to recruit Cdc42 and other polarity establishment proteins and signaling molecules, thus amplifying the signal of locally activated pheromone receptors, leading to both polarized growth and a full level of transcriptional induction. Our results are consistent with the idea that polarized hyphal growth in C. albicans is regulated through mechanisms similar to those for mating in S. cerevisiae.

In addition to the F-actin-dependent Cdc42 localization at the hyphal tip, polarized growth during hyphal induction in C. albicans is analogous to mating projection formation in S. cerevisiae in the following aspects: (i) neither shmoos nor hyphal germ tubes have constrictions at their base; (ii) shmoos are formed in G1-arrested cells, and polarized growth in hyphae can also occur before the G1/S transition (13); and (iii) both mating cells of S. cerevisiae and hyphal cells of C. albicans have a noncytokinetic septin ring around the base of the shmoo or hypha (10, 24). This ring is also much fainter and less organized than the cell cycle-associated septin ring at the site of septation.

The analogy between mating and hypha formation makes shmooing in S. cerevisiae an attractive model for hypha formation. This analogy implies that C. albicans may also use transmembrane receptors to respond to hypha-specific cues. However, such receptors have not been discovered to date, and chemotropism has not been demonstrated in C. albicans. In addition, hypha induction is probably more complex than the “one ligand-one receptor” model of mating. Not only serum and hormones (such as estrogen [27]) are hyphal inducers; growth conditions such as pH, heat, and starvation also induce hyphae. Despite this, it is still possible that less conserved receptors are used to signal hyphal morphogenesis in C. albicans, because the functions of the core regulatory molecules, such as Cdc42 and actin, are highly conserved. We favor the model which suggests that clustering of receptors by F-actin and other molecules mediates sustained Cdc42 localization, which then amplifies the signal for polarized growth during hyphal morphogenesis and allows efficient signal transduction for transcriptional induction of hypha-specific genes.

Acknowledgments

We thank Cormack for providing the C. albicans GFP construct and Zhen Tian for help with the Northern analysis.

This work was supported by a grant from the NIH (GM-55155).

REFERENCES

- 1.Adams, A. E., D. I. Johnson, R. M. Longnecker, B. F. Sloat, and J. R. Pringle. 1990. CDC42 and CDC43, two additional genes involved in budding and the establishment of cell polarity in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Cell Biol. 111:131-142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adams, A. E. M., and J. R. Pringle. 1991. Staining of actin with fluorochrome-conjugated phalloidin. Methods Enzymol. 194:729-731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson, J. M., and D. R. Soll. 1986. Differences in actin localization during bud and hypha formation in the yeast Candida albicans. J. Gen. Microbiol. 132:2035-2047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ayscough, K. R., and D. G. Drubin. 1998. A role for the yeast actin cytoskeleton in pheromone receptor clustering and signalling. Curr. Biol. 8:927-930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ayscough, K. R., J. Stryker, N. Pokala, M. Sanders, P. Crews, and D. G. Drubin. 1997. High rates of actin filament turnover in budding yeast and roles for actin in establishment and maintenance of cell polarity revealed with the actin inhibitor latrunculin-A. J. Cell Biol. 137:399-416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chant, J., and I. Herskowitz. 1991. Genetic control of bud site selection in yeast by a set of gene products that constitute a morphogenetic pathway. Cell 65:1203-1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cormack, B. P., R. H. Valdivia, and S. Falkow. 1996. fluorescence-activated cell sorting-optimized mutants of the green fluorescent protein (GFP). Gene 173:33-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coue, M., S. L. Brenner, I. Spector, and E. D. Korn. 1987. Inhibition of actin polymerization by latrunculin A. FEBS Lett. 213:316-318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feng, Q., E. Summers, B. Guo, and G. Fink. 1999. Ras signaling is required for serum-induced hyphal differentiation in Candida albicans. J. Bacteriol. 181:6339-6346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Giot, L., and J. B. Konopka. 1997. Functional analysis of the interaction between Afr1p and the Cdc12p septin, two proteins involved in pheromone-induced morphogenesis. Mol. Biol. Cell 8:987-998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Greenberg, M. E. 1987. Preparation and analysis of RNA, chapter 4. In F. M. Ausubel et al. (ed.), Current protocols in molecular biology, vol. 1. John Wiley and Sons, Inc., New York, N.Y.

- 12.Gulli, M. P., and M. Peter. 2001. Temporal and spatial regulation of rho-type guanine-nucleotide exchange factors: the yeast perspective. Genes Dev. 15:365-379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hazan, I., M. Sepulveda-Becerra, and H. Liu. 2002. Hyphal elongation is regulated independently of cell cycle in Candida albicans. Mol. Biol. Cell 13:134-145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kron, S. J., and N. A. Gow. 1995. Budding yeast morphogenesis: signalling, cytoskeleton and cell cycle. Curr. Opin.Cell Biol. 7:845-855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lo, H. J., J. R. Kohler, B. DiDomenico, D. Loebenberg, A. Cacciapuoti, and G. R. Fink. 1997. Nonfilamentous C. albicans mutants are avirulent. Cell 90:939-949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Loeb, J. D., M. Sepulveda-Becerra, I. Hazan, and H. Liu. 1999. A G1 cyclin is necessary for maintenance of filamentous growth in Candida albicans. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:4019-4027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Merla, A., and D. I. Johnson. 2000. The Cdc42p GTPase is targeted to the site of cell division in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 79:469-477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mirbod, F., S. Nakashima, Y. Kitajima, R. D. Cannon, and Y. Nozawa. 1997. Molecular cloning of a rho family, CDC42Ca gene from Candida albicans and its mRNA expression changes during morphogenesis. J. Med. Vet. Mycol. 35:173-179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mosch, H. U., T. Kohler, and G. H. Braus. 2001. Different domains of the essential GTPase Cdc42p required for growth and development of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:235-248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nern, A., and R. A. Arkowitz. 2000. G proteins mediate changes in cell shape by stabilizing the axis of polarity. Mol. Cell 5:853-864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Park, H. O., A. Sanson, and I. Herskowitz. 1999. Localization of bud2p, a GTPase-activating protein necessary for programming cell polarity in yeast to the presumptive bud site. Genes Dev. 13:1912-1917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Richman, T. J., M. M. Sawyer, and D. I. Johnson. 2002. Saccharomyces cerevisiae Cdc42 localizes to cellular membranes and clusters at sites of polarized growth. Euk. Cell 1:458-468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sherman, F. 1991. Getting started with yeast. Methods Enzymol. 194:12-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sudbery, P. E. 2001. The germ tubes of Candida albicans hyphae and pseudohyphae show different patterns of septin ring localization. Mol. Microbiol. 41:19-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Theesfeld, C. L., J. E. Irazoqui, K. Bloom, and D. J. Lew. 1999. The role of actin in spindle orientation changes during the Saccharomyces cerevisiae cell cycle. J. Cell Biol. 146:1019-1032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ushinsky, S. C., D. Harcus, J. Ash, D. Dignard, A. Marcil, J. Morchhauser, D. Y. Thomas, M. Whiteway, and E. Leberer. 2002. CDC42 is required for polarized growth in human pathogen Candida albicans. Euk. Cell 1:95-104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.White, S., and B. Larsen. 1997. Candida albicans morphogenesis is influenced by estrogen. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 53:744-749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yokoyama, K., H. Kaji, K. Nishimura, and M. Miyaji. 1994. The role of microfilaments and microtubules during pH-regulated morphological transition in Candida albicans. Microbiology 140:281-287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ziman, M., D. Preuss, J. Mulholland, J. M. O'Brien, D. Botstein, and D. I. Johnson. 1993. Subcellular localization of Cdc42p, a Saccharomyces cerevisiae GTP-binding protein involved in the control of cell polarity. Mol. Biol. Cell 4:1307-1316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]