Abstract

The dimorphic fungi Blastomyces dermatitidis and Histoplasma capsulatum cause systemic mycoses in humans and other animals. Forward genetic approaches to generating and screening mutants for biologically important phenotypes have been underutilized for these pathogens. The plant-transforming bacterium Agrobacterium tumefaciens was tested to determine whether it could transform these fungi and if the fate of transforming DNA was suited for use as an insertional mutagen. Yeast cells from both fungi and germinating conidia from B. dermatitidis were transformed via A. tumefaciens by using hygromycin resistance for selection. Transformation frequencies up to 1 per 100 yeast cells were obtained at high effector-to-target ratios of 3,000:1. B. dermatitidis and H. capsulatum ura5 lines were complemented with transfer DNA vectors expressing URA5 at efficiencies 5 to 10 times greater than those obtained using hygromycin selection. Southern blot analyses indicated that in 80% of transformants the transferred DNA was integrated into chromosomal DNA at single, unique sites in the genome. Progeny of B. dermatitidis transformants unexpectedly showed that a single round of colony growth under hygromycin selection or visible selection of transformants by lacZ expression generated homokaryotic progeny from multinucleate yeast. Theoretical analysis of random organelle sorting suggests that the majority of B. dermatitidis cells would be homokaryons after the ca. 20 generations necessary for colony formation. Taken together, the results demonstrate that A. tumefaciens efficiently transfers DNA into B. dermatitidis and H. capsulatum and has the properties necessary for use as an insertional mutagen in these fungi.

The systemic dimorphic fungi Blastomyces dermatitidis and Histoplasma capsulatum are animal pathogens that inhabit moist, high-organic-matter environmental niches as filamentous, sporulating molds (2, 21). In the lungs of a host, inhaled spores germinate into budding yeast, and infection can spread to other tissues of the body (9, 19). The phase transition from mold to yeast, and back, can be accomplished in the lab by shifting the temperature between 22 and 37°C, respectively. Although immunocompetent hosts are susceptible to infection, immunodeficient hosts such as AIDS patients are particularly at risk.

The genetic tools for studying these pathogenic fungi have been accumulating over the past decade (5, 24), and important virulence factors for both organisms have been identified. BAD1, an adhesin and immune modulator, is essential for the virulence of B. dermatitidis (6, 16). CBP1, a calcium binding protein of H. capsulatum, is essential for macrophage killing and virulence (33). Both of these virulence factors were identified by the reverse genetic approach of candidate gene disruption. A forward genetic approach of mutagenesis and phenotypic screening would be valuable for identifying other virulence factors or factors involved in regulation of other processes such as phase transition. This can be a powerful approach when mutagenesis involves random insertions of a known DNA sequence into the genome. The insertion sequence tag can then be used to clone the adjoining DNA for analysis. One highly successful insertional mutagenesis approach in plants utilizes the Agrobacterium tumefaciens transfer DNA (T-DNA)-transferring type IV secretion system (23, 36, 37).

The plant pathogen A. tumefaciens carries a ∼200-kbp tumor-inducing (Ti) plasmid, within which is a portion referred to as T-DNA. Upon infection of plants, the T-DNA is randomly inserted into the plant genome and transforms the plant cells to a tumorous growth called a crown gall, which serves as host tissue for the growth of the bacterium (17, 38). Plant biologists have modified the Ti plasmid to remove tumor-causing and superfluous genes but keep the genes necessary for T-DNA transfer and integration into nuclear DNA (3). In addition, binary vectors have been developed whereby the T-DNA region is harbored in trans from the rest of the Ti plasmid (4). The binary vectors are smaller, can replicate in Escherichia coli, have selectable markers for growth in E. coli or plants, and provide cloning sites for addition of foreign DNA within the T-DNA. These binary vectors have been put to great use as insertional mutagens in plants and have been shown, with modification, to transfer T-DNA into Saccharomyces cerevisiae yeast (7), filamentous fungi (12), and, recently, the dimorphic fungus Coccidioides immitis (1). Changes necessary for use in fungi include addition of fungal selectable markers to the T-DNA and induction of the A. tumefaciens vir genes by special culture conditions. The medium used to induce the vir genes mimics the composition of wounded plant cell exudates, with a low pH, a high monosaccharide concentration, and the chemical acetosyringone (AS). One crucial property that has made this method useful for subsequent analysis of the tagged gene in plants is that most often only a single site of insertion is generated per transformant (12). This feature greatly simplifies the demonstration that the tagged gene represents the mutation responsible for the phenotype.

B. dermatitidis presents one potential obstacle to the use of a mutagenesis-phenotypic-screen approach for identifying fungal genes in a pathway: it is multinucleate. One study indicated an average of 3 to 4 nuclei per yeast for five different strains (11). Insertion mutations that result in a recessive phenotype would not be expressed if only one nucleus out of four is transformed. This problem can be circumvented by transformation of uninucleate conidia (12) or by performing multiple rounds of colonial growth under selection, which has been shown to result in the production of homokaryotic transformants for some multinucleate fungi (15). Since H. capsulatum yeast posses a single haploid nucleus, expression of recessive phenotypes should be possible (8).

Although previous experiments have shown that it is possible to transform B. dermatitidis and H. capsulatum via electroporation, this technique is not ideal for mutagenesis. Transforming DNA integrates randomly in the genome, but often at multiple sites in B. dermatitidis (18; unpublished data). In the present work, we developed the tools necessary for A. tumefaciens T-DNA transfer into B. dermatitidis and H. capsulatum, and we demonstrate here that this methodology generates the required fate of integrated DNA and the additional features necessary for the use of A. tumefaciens T-DNA as an insertional mutagen in these dimorphic fungi. One essential feature is that B. dermatitidis multinucleate yeast gives rise to homokaryotic progeny during outgrowth of transformed cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Fungal strains.

B. dermatitidis strains 26199, 60915, and 60636 were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; Manassas, Va.). Strain ER-3 (2) was obtained from D. Baumgardner (Department of Family Medicine, University of Wisconsin Medical School, Milwaukee). Spontaneous (ER-3ura5-s11) and UV-induced (ER-3ura5-v33) uracil auxotrophic lines were obtained via fluoroorotic acid selection of germinating condidia (unpublished data). Strains SLH1312 and SLH14081 are patient isolates obtained from the Wisconsin State Laboratory of Hygiene (SLH; Madison, Wis.). H. capsulatum strains G217B (ATCC 26032), G217Bura5-23 (26), G184AR (ATCC 26027), and G184AS (22) were provided by Jon Woods (University of Wisconsin, Madison); strain SLHc4 is a patient isolate from the SLH.

Prototrophic B. dermatitidis strains were maintained at 37°C as yeast on 7H10 agar slants supplemented with oleic acid-albumin-dextrose-catalase (Difco, Detroit, Mich.). ura5 auxotrophic strains of B. dermatitidis were maintained on 3M agar medium (43) made without hemin but with an additional 10 μM FeSO4 and 100 μg of uracil/ml. H. capsulatum was maintained at 37°C on HMM agar (43) supplemented with uracil at 100 μg/ml for ura5 auxotrophic strains. H. capsulatum was incubated in the presence of 5% CO2-95% air. HMM and 3M agar media were made by using SeaKem LE Agarose (BioWhittaker Molecular Applications, Rockland, Maine)

B. dermatitidis strain ER-3 was converted to mold and sporulated by inoculating potato flake agar plates (29) with approximately 106 yeast cells and maintaining the cultures at room temperature (∼22°C) for 2 to 3 weeks. Spores were harvested by flooding the plates with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and gently rubbing the surfaces with a glass rod. Released spores were centrifuged at 2,000 × g for 10 min and then resuspended to the desired concentration in HMM.

Plasmid and bacterial manipulations.

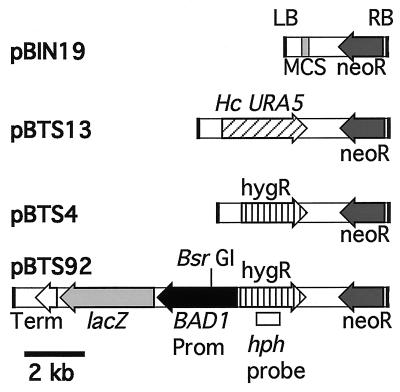

The binary vector pBIN19 (4) (GenBank accession no. 520486) and A. tumefaciens strain LBA1100, harboring the Ti plasmid pAL1100 (3), were obtained from C. van den Hondel (Leiden University, Leiden, The Netherlands). Plasmids pBTS4 and pBTS92 have been described previously (30). pBTS13 was constructed by inserting the SalI/HindIII fragment containing the H. capsulatum URA5 gene from plasmid pWU20 (42) into the SalI/HindIII sites of pBIN19. These binary plasmids were introduced into E. coli strain XL1-Blue (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.) via electroporation (Gene Pulser; Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.) according to the manufacturer's instructions, and transformants were isolated by kanamycin selection (50 μg of kanamycin/ml in Luria-Bertani [LB] agar plates). Confirmed plasmids were introduced into A. tumefaciens strain LBA1100 via electroporation (14). A. tumefaciens transformants were isolated on LB agar plates supplemented with 0.1% glucose, 100 μg of kanamycin/ml, and 100 μg of spectinomycin/ml (to select for maintenance of the Ti plasmid). Figure 1 depicts the T-DNA portion of the plasmids used in this study.

FIG. 1.

Binary vectors used for these studies are based on pBIN19 (4). Only the T-DNA region, flanked by the right (RB) and left (LB) borders, is shown for each plasmid. Elements present in pBIN19 or cloned into the multiple cloning site (MCS) to produce the other plasmids are indicated: neoR, neomycin or G418 resistance, conferred by the nptII gene cassette; Hc URA5, the H. capsulatum URA5 gene (42); hygR, hygromycin resistance, conferred by the hph gene cassette from pAN7-1 (28); BAD1 Prom, 2.6 kb from B. dermatitidis BAD1 5′-flanking sequences, starting at the translation start codon; lacZ, E. coli β-galactosidase gene coding region; Term, Aspergillus nidulans trpC 3′-flanking sequence from pAN7-1. Arrows indicate transcriptional orientation for each fragment. The BsrGI site and hph probe sequences used in Southern blot analyses of restricted DNA from pBTS92 transformants are indicated.

Fungal transformation.

The protocols for A. tumefaciens-mediated transformation of yeast and filamentous fungi (7, 12) were adapted for B. dermatitidis and H. capsulatum yeast. A heavy inoculum of A. tumefaciens strain LBA1100, carrying the desired binary plasmid, was incubated overnight (18 to 24 h) at 28°C in Agrobacterium minimal medium (MM) (20) supplemented with kanamycin and spectinomycin at 100 μg/ml. The culture was diluted to an A660 of 0.05 in induction medium (IM) (7) supplemented with 200 μM AS (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) and again incubated overnight to achieve an A660 of ∼0.6. For some experiments, this second overnight culture was concentrated by centrifugation at 5,000 × g for 5 min, and the pellet was resuspended in IM to an A660 of 10.0.

Yeast-phase cells of B. dermatitidis and H. capsulatum were harvested at 2 to 4 days of growth, counted by using a hemocytometer (individual cells as well as small clusters were counted as one), and centrifuged at 800 × g for 5 min. The supernatant was removed, and the cell pellet was resuspended in HMM to give up to 2 × 108 cells per ml for B. dermatitidis and 6 × 109 cells per ml for the smaller yeast, H. capsulatum. For cocultivation, 100 μl of A. tumefaciens in IM and 100 μl of yeast in HMM were mixed and spread onto a BiodyneA nylon membrane (Pall Gelman, Ann Arbor, Mich.) on an IM agarose plate containing 200 μM AS. Cocultivation plates were incubated at 28°C for 3 days. (For transformation of germinating spores, cocultivation with A. tumefaciens was done at 22°C.) Following cocultivation, the membranes were transferred to either HMM or 3M selection medium containing 200 μM cefotaxime (Sigma). Hygromycin B (Calbiochem, San Diego, Calif.) selection was done at 100 μg/ml for B. dermatitidis and 200 μg/ml for H. capsulatum. 3M plates (without uracil) were used to select uracil prototrophs. Selection plates were incubated at 37°C for 2 to 4 weeks to monitor production of colonies, which were enumerated and picked for further analysis. At least one of three types of negative-control experiments was performed for each transformation experiment: (i) cultivation of yeast without A. tumefaciens, (ii) cocultivation with A. tumefaciens but under noninducing (without AS) conditions, or (iii) cocultivation under inducing (with AS) conditions with A. tumefaciens harboring a binary vector plasmid lacking the selectable marker. In B. dermatitidis experiments, the frequency of spontaneous hygromycin resistance was zero but reversion of uracil auxotrophy was ∼5 × 10−8 per yeast cell. Therefore, for uracil selection experiments, the number of revertants was subtracted to arrive at the putative transformation frequency. For H. capsulatum transformed with the binary vector pBTS92, spontaneous hygromycin-resistant colonies appeared at a frequency of 0 to 6 × 10−7 per yeast, but the colonies all lacked lacZ; only lacZ+ colonies were counted for transformation frequency. No spontaneous uracil prototrophs were obtained by using uracil selection for transformation of H. capsulatum.

X-Gal stain for β-galactosidase activity.

To assess lacZ expression in putative transformants, either colonies were picked to an HMM plate containing 100 μg of X-Gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside; Promega, Madison, Wis.)/ml or the membrane containing intact colonies was moved to an X-Gal-containing plate. In both cases the plates were incubated overnight at 37°C and then inspected for cells containing a blue product indicating β-galactosidase activity. In some cases, after overnight staining, plates were stored at 4°C for several days to allow color development without further growth of colonies. For in situ photography of X-Gal-staining cells, membranes were placed overnight in neutral-buffered 10% formalin and then gently washed with PBS. In some cases, membranes were further processed by serial washes with increasing concentrations of ethanol (to 100%) and were air dried between layers of Whatman no. 1 paper. To detect transformants based on lacZ expression, cocultivations with ∼104 yeast cells and LBA1100::pBTS92 were performed as above for 3 days at 28°C. The membranes were transferred to 3M plates containing 200 μM cefotaxime for 5 to 7 days at 37°C and then to X-Gal plates to allow the development of blue foci on a lawn of nonstaining cells. Yeast cells from blue foci were picked and spread on 3M plates to generate individual colonies. X-Gal staining identified transformed-cell colonies.

Sytox Green nuclear stain.

Yeast cells from early-log-phase liquid cultures of B. dermatitidis ATCC 26199 in HMM were fixed overnight in neutral buffered 5% formalin, washed with 50 mM sodium citrate, pH 7.0, and treated for 90 min with 25 mg of RNase A/ml at 50°C. The yeast cells were washed three times with 50 mM sodium citrate and treated for >60 min at room temperature with 50 μM Sytox Green (Molecular Probes, Inc., Eugene, Oreg.). Stained yeast cells were stored in the dark at 4°C before being viewed with an Olympus BX60 microscope in either bright-field or fluorescent mode with 460- to 490-nm excitation filters and 515- to 550-nm emission filters.

Transformant PCR.

Putative transformants were tested for the presence of T-DNA by PCR amplification of either the hph gene (encoding hygromycin phosphotransferase, conferring Hygr) or the nptII gene (encoding neomycin phosphotransferase, conferring Neor). For nptII, a 542-bp fragment was amplified by using primers 5′-TCGGCAGGAGCAAGGTGAGAT and 5′-AGCCGCGGGTTTCTGGAGTTTAAT (Operon, Alameda, Calif.), Amplitaq DNA polymerase, and a reaction buffer containing 1.5 mM MgCl2 (Perkin-Elmer Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.) with a thermocycler program of 1 cycle at 94°C for 1 min, followed by 30 cycles of 1 min each at 94, 59, and 72°C, and 1 cycle of 72°C for 5 min. For hph PCR, an 822-bp fragment was amplified by using primers 5′-CGATGTAGGAGGGCGTGGATA and 5′-GCTTCTGCGGGCGATTTGTGT, 1.6 mM MgCl2, and 30 cycles as above, but with a 60°C annealing temperature.

DNA extraction and Southern blot hybridization.

Genomic DNA for use in PCR and Southern blot analysis of B. dermatitidis and H. capsulatum samples was obtained by using published protocols (18, 39, 41). Southern blot hybridizations were performed using standard protocols (32). The primary probe used to analyze the fate of transforming DNA was an 822-bp hph fragment made by PCR (described above). Another T-DNA probe was the trpC terminator sequence, subcloned from pAN7-1 (28) by PCR amplification using primers 5′-AGAGCTCGGATCCACTTAACGTTACTGA and 5′-TGAATTCTCGAGTGGAGATGTGGAGTGG. A 770-bp fragment was cut from the clone by using SacI and EcoRI. Non-T-DNA pBIN19 probes included the 7.9-kb BglII, the 2.4-kb BglII/NotI, or the 5.5-kb BglII/NotI fragment of pBIN19. Fragments were gel purified (Qiaquick Gel Extraction kit; Qiagen, Valencia, Calif.) and labeled with [32P]dCTP by using the Oligolabeling kit from Amersham Pharmacia Biotech (Piscataway, N.J.).

RESULTS

A. tumefaciens-mediated transformation of B. dermatitidis.

One rationale for using A. tumefaciens for transformation was the desire for a simple fate of T-DNA integration in the genome. In addition, not all strains of B. dermatitidis are transformed by electroporation (unpublished data). Starting with yeast-phase organisms, T-DNA plasmid pBTS4 or pBTS92 (Fig. 1), and hygromycin selection, several strains of B. dermatitidis were successfully transformed. For some strains the protocol gave rise to hundreds of transformants per cocultivation (Table 1). However, the transformation frequency (transformants per 106 target yeast cells) ranged over 2 orders of magnitude among strains tested within a single experiment. There was between-experiment variation in transformation frequency, but the ranking between strains was preserved. In initial experiments, putative transformants were checked for the presence of the hph gene by PCR (data not shown). In experiments utilizing pBTS92, putative transformants were confirmed by demonstrating with X-Gal that they had acquired the lacZ gene (data not shown). Negative-control experiments indicated that addition of AS was essential for transformation.

TABLE 1.

Agrobacteriuma-mediated transformation of B. dermatitidis by use of hygromycin selection

| Strain | No. of target cells/ cocultivation | No. of Hygr colonies/ cocultivation ± SDb | No. of Hygr colonies/ 106 target cells ± SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yeast | |||

| Expt 1 | |||

| 60915 | 1.0 × 107 | 211 ± 45 | 21.1 ± 4.5 |

| 26199 | 1.0 × 107 | 44 ± 65 | 4.0 ± 6.5 |

| Expt 2 | |||

| 26199 | 2.0 × 107 | 296 ± 118 | 14.8 ± 5.9 |

| ER-3 | 2.7 × 107 | 84 ± 41 | 3.1 ± 1.5 |

| 60636 | 7.5 × 106 | 2.0 ± 1.0 | 0.3 ± 0.2 |

| SLH1312 | 4.0 × 106 | 0.7 ± 1.0 | 0.2 ± 0.3 |

| SLH14081 | 3.0 × 106 | 0.3 ± 0.6 | 0.1 ± 0.2 |

| Expt 3 | |||

| 26199 | 1.4 × 107 | 658 ± 210 | 7.0 ± 15 |

| ER-3 | 1.6 × 107 | 24 ± 3.2 | 1.5 ± 0.2 |

| 60636 | 4.0 × 106 | 1.2 ± 2.4 | 0.3 ± 0.6 |

| SLH1312 | 1.4 × 106 | 0 | <0.7c |

| SLH14081 | 1.3 × 106 | 0 | <0.8c |

| Spores | |||

| Expt 4, ER-3 | 7.6 × 106 | 38 ± 15 | 5.0 ± 2.0 |

| Expt 5, ER-3 | 1.0 × 107 | 165 ± 140 | 16.5 ± 14.0 |

| Expt 6, ER-3 | 1.8 × 106 | 230 ± 32 | 128.0 ± 17.9 |

A. tumefaciens harboring plasmid pBTS4 for experiment 1; plasmid pBTS92 for experiments 2 through 6.

Mean ± standard deviation for three to five samples.

Number given is based on <1 colony per target cell population.

Because of the potential problem of multinucleate yeast producing heterokaryotic transformants, experiments were undertaken with germinating conidia of the sporulating strain ER-3. As with yeast, the conidia were successfully transformed by A. tumefaciens (Table 1). Although there was between-experiment variation here also, transformation frequency appears to be higher for ER-3 germinating conidia than for yeast (Table 1).

Cocultivation ratio of A. tumefaciens to B. dermatitidis.

To optimize transformation frequency, the effector-to-target ratio was altered. First, the number of A. tumefaciens cells in a cocultivation was increased or decreased while the amount of yeast was held constant. For C. immitis as a target, 500-fold changes in the amount of A. tumefaciens (up to 500 bacteria per target) produced a 10-fold change in transformation frequency (1). In contrast, with B. dermatitidis yeast and spores, 100-fold changes in the amount of A. tumefaciens (up to 180 bacteria per target) had no effect on the transformation frequency (data not shown). However, when the amount of A. tumefaciens was held constant (at 3 × 107 or 6 × 107 bacteria per cocultivation), and the amount of yeast was serially decreased to give up to 3,000 bacteria per target yeast, transformation frequencies increased dramatically (Table 2). In the extreme case, the transformation frequency was ∼104 transformants per 106 yeast cells, or about 1 per 100 targets (experiment 2, 26199 B).

TABLE 2.

High effector-to-target ratio during cocultivation dramatically increases the transformation frequency

| Strain | No. of yeast cells/ cocultivation | A. tumefaciens/B. dermatitidis ratioa | No. of Hygr colonies/ cocultivation ± SDb | No. of Hygr colonies/106 yeast cells ± SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Expt 1, ER-3 | 2 × 107 | 3 | 215 | 11 |

| 2 × 106 | 30 | 141 | 71 | |

| 2 × 105 | 300 | 147 | 735 | |

| 2 × 104 | 3,000 | 146 | 7,150 | |

| Expt 2 | ||||

| 26199 (A)c | 1 × 107 | 3 | >650 ± 99 | >65 ± 9.9 |

| 1 × 104 | 3,000 | 27 ± 7 | 2,767 ± 723 | |

| 26199 (B) | 1 × 107 | 3 | 17 ± 1.5 | 1.7 ± 0.15 |

| 1 × 104 | 3,000 | 100 ± 9 | 10,033 ± 907 |

A. tumefaciens harboring pBTS92 was used at 6 × 107 bacteria per cocultivation in experiment 1 and at 3 × 107 bacteria per cocultivation in experiment 2.

There were no replicates in experiment 1; in experiment 2, cocultivations were done in triplicate, so means ± standard deviations are given.

(A) and (B) are two different stocks of ATCC 26199.

A. tumefaciens-mediated transformation of H. capsulatum.

Several strains of H. capsulatum yeast were tested for A. tumefaciens-mediated transformation using the pBTS92 plasmid and hygromycin selection. All strains generated transformants, and although the transformation frequency was lower than for some B. dermatitidis strains, hundreds of transformants were produced per cocultivation. As with B. dermatitidis, the transformation efficiency of H. capsulatum varied between strains and experiments (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

A. tumefaciens-mediated transformation of H. capsulatum yeast by use of hygromycin selection

| Strain | No. of yeast cells/ cocultivation | No. of Hygr colonies/ cocultivation ± SDa | No. of Hygr colonies/ 106 yeast cells ± SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Expt 1 | |||

| G217B | 2.7 × 108 | 729 ± 54 | 2.7 ± 0.2 |

| SLHc4 | 5.7 × 108 | 741 ± 171 | 1.3 ± 0.3 |

| Expt 2 | |||

| G217B | 1.9 × 108 | 266 ± 57 | 1.4 ± 0.3 |

| 5.7 × 107 | 279 ± 29 | 4.9 ± 0.5 | |

| 1.7 × 107 | 158 ± 26 | 9.3 ± 1.5 | |

| G217Bura5-23b | 2.9 × 108 | 406 ± 58 | 1.4 ± 0.2 |

| SLHc4 | 3.4 × 108 | 272 ± 204 | 0.8 ± 0.6 |

| G184AS | 3.8 × 108 | 494 ± 38 | 1.3 ± 0.1 |

| G184ARc | 4.5 × 107 | 283 ± 77 | 6.3 ± 1.7 |

A. tumefaciens harboring pBTS92 was used; only lacZ+ colonies were counted; means ± standard deviations for three (experiment 2) or four (experiment 1) samples are given.

The selection medium was supplemented with 100 μg of uracil/ml.

G184AR (rough) forms large aggregates of cells, each counted as a single cell. This experiment was done with a mass of cells approximately equal to those of the other strains.

Comparison of hygromycin versus uracil selection.

The availability of uracil auxotrophic lines of B. dermatitidis and H. capsulatum allowed comparisons of the efficacy of uracil versus hygromycin selection in the A. tumefaciens transformation system. Direct comparisons were made by using the two binary plasmids pBTS4 and pBTS13 (Fig. 1). Table 4 shows two significant trends. First, the transformation frequency was 5- to 10-fold higher with uracil selection for both fungi, and second, transformed colonies appeared earlier under uracil selection. For most experiments, more than half the eventual number of colonies arose within the first 2 weeks of uracil selection. In contrast, more than 80% of the colonies developed after the first 2 weeks with hygromycin selection.

TABLE 4.

A. tumefaciens-mediated transformation with hygromycin versus uracil selection

| Strain | T-DNA plasmid | Selection | No. of transformants/106 target cells ± SDa at:

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 14 days | 32 days | |||

| B. dermatitidis yeast | ||||

| Expt 1 | ||||

| ER-3ura5-s11 | pBTS4 | H100b | 0.04 ± 0.08 | 0.4 ± 0.5 |

| pBTS13 | URAc | 4.4 ± 1.8 | 5.0 ± 1.6 | |

| ER-3ura5-v33 | pBTS4 | H100 | 0.03 ± 0.05 | 0.05 ± 0.05 |

| pBTS13 | URA | 0.4 ± 0.4 | 0.6 ± 0.4 | |

| Expt 2, ER-3ura5-s11 | pBTS4 | H100 | 1.2 ± 0.4 | 6.8 ± 1.2 |

| pBTS13 | URA | 17.0 ± 10.7 | 29.0 ± 0.6 | |

| B. dermatitidis spores, ER-3ura5-s11 (expt 3) | pBTS4 | H100 | 0.4 ± 0.7 | 5.0 ± 1.8 |

| pBTS13 | URA | 25.4 ± 3.1 | 41.7 ± 3.1 | |

| H. capsulatum yeast, G217Bura5-23 (expt 4) | pBTS4 | H200d | <0.03e | <0.03e |

| pBTS13 | URA | 0.4 ± 0.4 | 1.1 ± 0.2 | |

Means ± standard deviations for duplicate (experiment 4) or triplicate (experiments 1 to 3) samples.

H100, hygromycin selection at 100 μg/ml; plates were supplemented with 100 μg of uracil/ml.

3M medium without uracil supplement.

H200, hygromycin selection at 200 μg/ml; plates were supplemented with 100 μg of uracil/ml.

Value for <1 colony per target population (3.2 × 107).

Fate of transforming DNA.

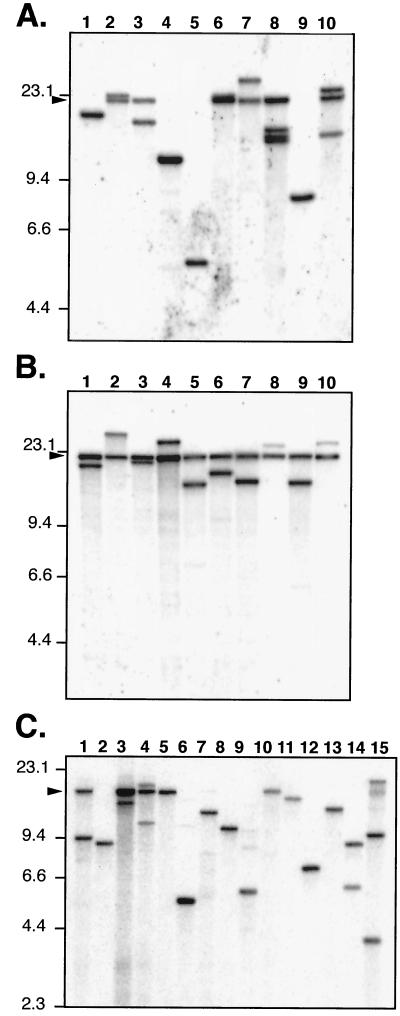

For both B. dermatitidis and H. capsulatum, the fate of T-DNA transferred from A. tumefaciens was analyzed by Southern blot hybridization. In both cases, analysis of undigested DNA indicated that the T-DNA had consistently inserted into chromosomal DNA and was not present as episomal plasmids, as is sometimes the case for H. capsulatum when the DNA is introduced by other means (39; data not shown). For transformants generated from the pBTS92 binary plasmid, genomic DNA was digested with BsrGI, which cuts once within the T-DNA, and blots were probed with a fragment of the hph gene so that only BsrGI fragments on the hph side of the T-DNA would be detected (Fig. 1). Under these conditions, each different site of T-DNA integration in the genome gives a single, unique hybridizing band, whose size is determined by the next site of BsrGI digestion in the adjoining DNA. If head-to-tail concatemers of transforming DNA are formed, as can be the case with B. dermatitidis electroporation (18), digestion at a single site in the sequence would give rise to an additional fragment that is equal to the unit length of the repeated DNA. Since either the T-DNA (defined by border sequence repeats) or the entire sequence of a binary vector can be transferred during A. tumefaciens-mediated transformation, the unit length of a concatemer repeat depends on the sequence transferred. For pBTS92 the predicted concatemer bands for T-DNA versus the entire plasmid would be 11.9 versus 20.3 kbp. Further analysis of the digested genomic DNA blots entailed hybridizing with probes for the non-T-DNA portions of the plasmid or with probes from the other side of the BsrGI site. These probes were used to confirm that some fragments represented transfer of the entire plasmid (i.e., hybridization with the non-T-DNA probes) and to confirm that the suspected concatemer band represents a unit length of transferred DNA.

Figure 2 shows Southern blots of 20 independent pBTS92 transformants of B. dermatitidis strain 26199 (Fig. 2A and B), and 15 transformants of H. capsulatum strain G217B (Fig. 2C). The transformants were generated by using A. tumefaciens at an A660 of 0.1 for Fig. 3A and an A660 of 10 for Fig. 3B, so that the ratio of A. tumefaciens to target yeast was 50 or 0.5, respectively. In all three panels the majority of lanes contain either a single, unique hybridizing band or a unique band plus an additional band representing the entire plasmid unit length, indicating a concatemer at the site of insertion. For 29 B. dermatitidis transformants analyzed in this way (Fig. 2A and B; also data not shown), there were 24 (83%) with single sites of insertion, 27 (93%) with a concatemeric band, and 26 (90%) in which the whole plasmid was transferred. Although the sample size was small (10 each), there were some differences in the fate of DNA between transformants obtained with large versus small amounts of bacteria during cocultivation. At high density (A660, 10; A. tumefaciens-to-yeast ratio, 50), the transformants all appeared to have single sites of insertion, although they all had multiple DNA copies at the site, giving rise to a concatemeric band equal to the full length of the plasmid (Fig. 2B). In contrast, in some of the cases where a low density of bacteria was used (A660, 0.1; A. tumefaciens-to-yeast ratio, 0.5), there is no apparent concatemeric band (Fig. 2A, lanes 1, 4, 5, and 9), but there are more cases of multiple sites of insertion (Fig. 2A, lanes 8 and 10). For 15 H. capsulatum transformants (Fig. 2C), 12 (80%) had single sites of integration, 6 (40%) had concatemeric bands, and 7 (47%) had the whole plasmid transferred.

FIG. 2.

Southern blot analyses indicate a simple fate of transforming DNA. A 5-μg portion of genomic DNA from yeast transformed with LBA1100::pBTS92 was digested with BsrGI and probed with hph (Fig. 1). Each lane represents an independent transformant. Molecular mass standards are indicated in kilobase pairs on the left. Arrowheads on the left show the migration position of linearized pBTS92 plasmid. (A) B. dermatitidis, cocultivations done with A. tumefaciens at an A660 of 0.1. (B) B. dermatitidis, cocultivations done at an A660 of 10. (C) H. capsulatum, cocultivations done at an A660 of 0.7.

FIG. 3.

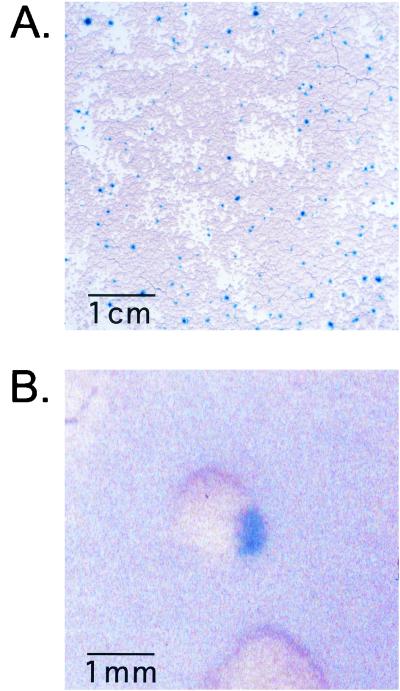

High-frequency transformation permits visible selection of transformants with lacZ expression. B. dermatitidis yeast was cocultivated with LBA1100::pBTS92 at a high ratio of bacteria to yeast. After 5 to7 days of unselected growth, the yeast cells were stained in situ with X-Gal and processed for photography. (A) A total of 2 × 104 ER-3 yeast cells were cocultivated with ∼6 × 107 bacteria. Individual blue-staining foci of lacZ+ cells are seen on a tan background of untransformed B. dermatitidis. Note 1-cm scale bar. (B) A total of 103 strain 26199 yeast cells were cocultivated with 3 × 107 bacteria. A close-up image of a single blue-sectored colony is shown. Note 1-mm scale bar.

Homokaryotic progeny following B. dermatitidis transformation.

For A. tumefaciens-mediated transformation to be useful in insertional mutagenesis of multinucleate B. dermatitidis yeast, transformed cells must yield homokaryotic progeny so that recessive mutations can be detected in phenotypic screens; this is not an issue for the uninucleate yeast form of H. capsulatum. One approach to generation of homokaryotic progeny has been to subject multinucleate fungi to multiple rounds of selection (15). A mutant screen involving thousands of transformants would be greatly complicated by the need for multiple rounds of colony selection for each transformant. Therefore, we tested whether a transformed colony produced with a single round of selection (i.e., selection only during primary colony growth) contained mostly homokaryotic cells.

The relative proportion of transformed or parental nuclei (as a measure of the degree of homokaryosis in the colony) was determined by converting the yeast to mold and sporulating the mold to trap a single haploid nucleus in each spore. The genotype of the nucleus in a spore can be determined by growing individual yeast colonies from each spore and testing for the transformed or parental phenotype. If most of the cells in a colony are homokaryotic, when the yeast cells convert to mold and sporulate, most of the haploid spores would contain transformed nuclei and give rise to transformed colonies. If, on the other hand, most of the cells in a colony remain heterokaryotic, two kinds of spores would be produced, harboring either a transformed or a parental nucleus. When these spores are germinated and grown as yeast, the resulting colonies would display either the transformed or the parental phenotype.

B. dermatitidis strain ER-3 was transformed with pBTS92 via A. tumefaciens, and hygromycin-resistant transformants were selected, plated for single-colony isolation without selection, and amplified to produce yeast to inoculate sporulation plates. Spores were harvested and plated to generate isolated yeast colonies at 37°C. Resulting colonies were stained with X-Gal to determine if the spore that gave rise to the colony harbored a transformed nucleus that could express the lacZ gene from the pBTS92 T-DNA.

The progeny of five independent transformants were tested in this manner. Over 600 progeny colonies were scored for each transformant, and all colonies were β-galactosidase positive, indicating that, at the time of sporulation, each of the transformants was homokaryotic. These results suggest that it is not necessary to go through multiple rounds of colonial selection to achieve homokaryosis for the majority of cells.

Homokaryons generated without antibiotic selection.

The previous result could be explained by several models: selective growth advantage of homokaryons over heterokaryons in hygromycin, yeast bud formation with a single nucleus, or nuclear sorting to form homokaryons independently of selection. Organelle sorting is seen for segregating chloroplasts in plant cells with a heteroplastidic constitution. Following rounds of nonselective division, homoplastidic progeny arise with one or the other of the chloroplastic types (25, 31). Further experiments were performed to test predicted aspects of these models.

If homokaryons arise under antibiotic selection because of a growth advantage of homokaryotic cells over heterokaryons, then transformants obtained in the absence of antibiotic selection would be predicted to maintain a heterokaryotic condition. If, however, the homokaryotic cells arose as a result of nuclear sorting, independent of antibiotic, then they should still arise in the absence of antibiotics. To test these predictions, and to differentiate between the selection and sorting models, transformations were performed without antibiotic selection. Transformants were identified by lacZ gene expression from transforming DNA. This approach was feasible with the high frequency of transformation obtained at high A. tumefaciens-to-B. dermatitidis ratios (Table 2).

ER-3 yeast cells were transformed with pBTS92, by using ∼104 target yeast cells per plate, and transformants were identified by staining with X-Gal. Foci of blue-staining cells representing transformed cell clones developed within the yeast lawn (Fig. 3A). β-Galactosidase-positive cells from the blue foci were colony purified and sporulated, and progeny were tested for homokaryosis, as was done above for hygromycin-selected transformants. For each of 9 independent clones (i.e., from separate blue foci), over 300 progeny were tested and all were lacZ+, indicating that the vast majority of sporulating cells harbored only transformed nuclei. An additional clone was progeny tested and gave rise to 1 colony lacking lacZ and 260 lacZ+ colonies, suggesting that, for this line, the population that was sporulated was not completely homokaryotic.

The sorting model predicts that, in the absence of antibiotic selection, both parental and transformed homokaryotic progeny should form in the generation of a colony derived from a yeast with one transformed nucleus and several nontransformed, parental nuclei. The resulting colony should then have sectors with lacZ+ cells and cells lacking lacZ. Several colonies with this phenotype were generated in experiments performed under high-frequency transformation conditions; one such colony can be seen in Fig. 3B.

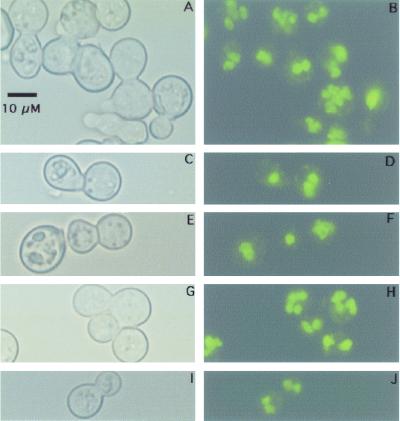

Budding in multinucleate B. dermatitidis yeast.

Our results suggest that, following transformation of a single nucleus in a multinucleate yeast cell, cycles of budding give rise to homokaryotic progeny which eventually outnumber heterokaryons. This would be the obvious result if only a single nucleus segregated into each bud. Once a bud forms with a single nucleus, then that bud's progeny would be homokaryotic in all subsequent generations. If more than one nucleus segregates into a bud, other mechanisms for generating homokaryons must be invoked (see Discussion). To analyze the nuclear composition of buds, we stained the DNA in budding cells and looked for uni- or multinucleate bud formation. During this analysis many multinucleate cells and buds were sited for both wild-type and transformed strains of B. dermatitidis (Fig. 4A and B) (data not shown). Since most buds analyzed are separated from the mother cell by a septum, it is not possible to exclude a model in which uninucleate buds generate multinucleate yeast by multiple rounds of nuclear division following formation of septa. In a minority of cases (∼10% of 300 buds analyzed), individual septate buds possessed a single nucleus (Fig. 4C to F) (data not shown). However, in many instances unseptated buds possessed more than one nucleus, as seen in Fig. 4G to J, suggesting that multinucleate buds may form by nuclear migration rather than solely by nuclear division. The results indicate that models for both uni- and multinucleate bud formation during B. dermatitidis yeast growth should be considered for explaining the production of homokaryons.

FIG. 4.

Multinucleate B. dermatitidis yeast cells produce buds with one or more nuclei. Early-log-phase yeast cells of strain 26199 were harvested, fixed, RNase treated, and stained with Sytox Green. Panels are paired horizontally so that the same field is shown viewed with bright-field microscopy (A, C, E, G, and I) or fluorescence (B, D, F, H, and J, respectively). (A and B) Several multinucleate cells are shown. (C, D, E, and F) Budding pairs with septa and a single nucleus apparent in the bud. (G, H, I, and J) Budding pairs without septa and multiple nuclei in the bud. All panels are shown with the same magnification. A scale bar is shown in panel A.

DISCUSSION

A. tumefaciens-mediated transformation of B. dermatitidis and H. capsulatum.

Although A. tumefaciens-mediated transformation of B. dermatitidis resembles transformation by electroporation with regard to the insertional fate of DNA at apparently random positions in the genome and the frequent formation of direct-repeat concatemers, it differs in important ways. First, the transformation frequency is higher with A. tumefaciens (18) (Tables 1 and 2) (data not shown). This is important for strains for which electroporation failed to generate transformants but that exhibited low-frequency transformation via A. tumefaciens (Tables 1 and 2) (data not shown). The T-DNA transformation system has also allowed the introduction of constructs, such as the lacZ expression cassette, which was not possible via electroporation (30) (Tables 1 and 2) (data not shown). As seen for several filamentous fungi (12), B. dermatitidis spores could also be used as a target for A. tumefaciens-based transformation (Table 1).

For both B. dermatitidis and H. capsulatum, the transformation frequency via A. tumefaciens is 5- to 10-fold higher by use of uracil prototroph selection compared to selection for resistance to hygromycin (Table 4). This finding could result from the high level of hygromycin necessary to suppress the growth of spontaneous hygromycin-resistant colonies, and a similar difference in transformation efficiency has been previously reported for H. capsulatum transformed via electroporation (40).

As found with electroporation, there can be variation in the transformation efficiency between strains and experiments (Tables 1 to 4). The cause for this variation was not determined, but it could result from differences in cell wall components or DNA metabolism, linked to differences in growth conditions and cell cycle. Preliminary experiments indicated that older plate cultures of B. dermatitidis were less efficiently transformed with A. tumefaciens (unpublished data).

A second important difference between A. tumefaciens- and electroporation-based transformation is the fate of transforming DNA. Published data for B. dermatitidis indicate that approximately two-thirds of transformants via electroporation had more than one site of DNA integration (18), and this fate also occurs in H. capsulatum (unpublished data). For both B. dermatitidis and H. capsulatum, T-DNA insertions occur at single sites in the genome in more than 80% of the cases tested (Fig. 2). This fate is essential for the easy cloning and analysis of insertion alleles. Since neither B. dermatitidis nor H. capsulatum has a facile genetic system for linkage mapping of a mutant phenotype to a DNA insertion site, the presence of multiple insertion sites would severely complicate analysis of mutants. With a single site of insertion, that site can be confirmed as the source of a mutant phenotype by complementing the defect with a wild-type allele. The wild-type allele would be cloned using the sequence information from the allele containing the T-DNA insertion. With more than one site of insertion, each would have to be cloned, analyzed, and complemented to determine which one is responsible for the mutant phenotype. Concatemers with multiple copies of the T-DNA at the site of integration (Fig. 2) should not interfere with cloning of the flanking DNA by use of a protocol such as Adapter PCR (34), which depends only on the plasmid sequence being available for primer binding.

Generation of homokaryotic transformants in multinucleate B. dermatitidis yeast.

As used in plant mutagenic screens and as expected in general, insertional mutagenesis should often disrupt gene function and cause a recessive phenotype. However, with one nucleus harboring an insertion mutation in a yeast cell containing two or more wild-type nuclei, the yeast would often retain the wild-type phenotype. Therefore, it would be necessary to convert heterokaryotic yeast to the homokaryotic condition to uncover a recessive phenotype.

The results of spore progeny testing following hygromycin selection demonstrated that a single round of colony growth under selection generates homokaryotic lines. Surprisingly, the results from the visual selection of lacZ+ primary transformants indicated that homokaryotic progeny are generated even in the absence of antibiotic selection. This result was unexpected, as the drug-selective advantage of homokaryotic versus heterokaryotic transformants was believed to be the mechanism for obtaining homokaryons with antibiotic selection (15). An alternative model is that during budding only one nucleus segregates into a bud. If this were the case, only homokaryotic progeny would be produced from heterokaryotic cells. These would be either of the transformed or of the parental type, but under hygromycin selection, only the transformed ones would survive. Although published studies have reported occasional yeast cells with a single nucleus (11, 13), there has been no systematic analysis of the number of nuclei transferred to a bud in B. dermatitidis. Our own nuclear staining analysis of yeast cells from early-log-phase cultures indicated a minority of cells (∼10%) with a single nucleus. During this analysis, budding cells were found in which more than one nucleus was present in the bud before septum formation. This finding suggests that multinucleate daughter cells do not all form with a single nucleus but could form via migration of more than one nucleus. Together, the data indicate that there is relaxed control of the number of nuclei per bud, and models based solely on uninucleate buds are insufficient to explain the experimental results.

Another possibility is that, by random sorting of nuclei during generations of budding, there is a cumulative increase of homokaryotic progeny, which eventually outnumber heterokaryons in the population. A similar phenomenon, unselected segregation of organelles, occurs following somatic fusion of plant protoplasts (31) and pertains to nuclear sorting in Aspergillus species (27).

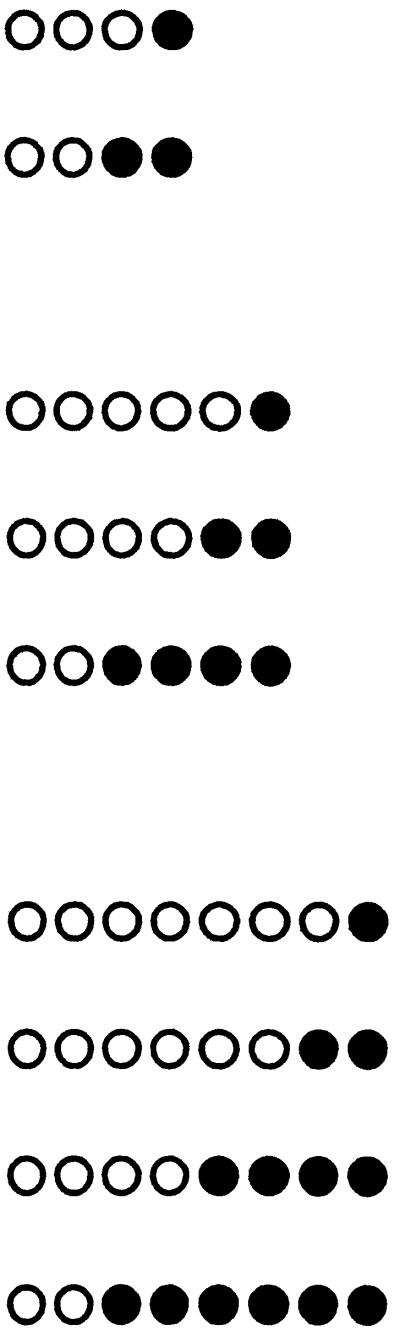

Mathematical modeling of homokaryosis in B. dermatitidis.

On the basis of random sampling of nuclei during budding, one can calculate the probability for each generation that a progeny cell will be either homo- or heterokaryotic. The proportion of each will depend on the total number of nuclei before budding and on the fraction of parental and transformed nuclei. To predict outcomes of colony formation based on random sorting, calculations were made with four, six, or eight total nuclei per yeast cell, of which one or more are mutant or transformed (the number selected for each bud was set at half the total number of nuclei [Table 5]). These form a subset of the possible combinations that could apply to B. dermatitidis budding yeast and cover a range consistent with nuclear numbers determined microscopically (Fig. 4; also data not shown). In Table 5, the number of combinations (C) of selecting nuclei (B) for a bud from a pool of total nuclei (N) is calculated by the equation C = N!/B! (N − B)!. As the number of nuclei increases, so does the number of possible combinations. In addition, the expected fraction of progeny with different genotypes at each generation depends on the number of parental and mutant nuclei in the prebud yeast.

TABLE 5.

Expected proportion of homokaryotic and heterokaryotic progeny produced by random sorting at each generation and cumulative effect of this sorting over generations

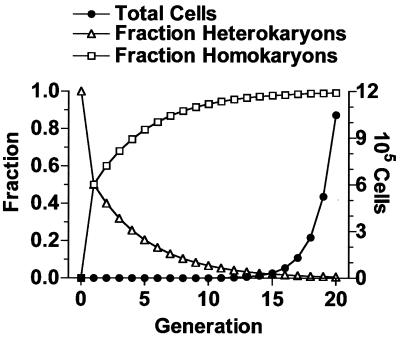

The cumulative effect of losing a fraction of each set of offspring to the homokaryotic classes over many generations is that eventually the homokaryons greatly outnumber the heterokaryons. The heterokaryon population grows not at the expected rate of doubling at each generation (i.e., total cells = 2t, where t is the number of generations) but at a reduced rate (e.g., 1.33t, if one-third of the cells formed are homokaryotic). In contrast, as homokaryotic cells are produced, they will double in subsequent generations. The population and genotype dynamics for the case of 4 nuclei per yeast cell with two nuclei per bud are shown in Fig. 5. From cells with one of four nuclei transformed, the expected progeny would be an equal proportion of parental homokaryons and heterokaryons. During subsequent generations, heterokaryons would give rise to progeny with expected proportions of two-thirds heterokaryons and one-sixth each parental and mutant homokaryons. The cumulative effect would decrease the proportion of heterokaryons in the population so that in 20 generations, 99.3% of the progeny would be homokaryotic, equally divided between parental and mutant types (Fig. 5). Twenty generations (∼106 yeast cells) fits with estimates for a visible B. dermatitidis colony (data not shown).

FIG. 5.

Theoretical nuclear sorting to generate homokaryotic progeny. The calculations are based on the assumptions of four nuclei per cell at the time of budding, random selection of two nuclei for the bud, and equal nuclear duplication to regenerate four nuclei per cell before the next budding. The total number of cells doubles at each generation. The graph shows the consequence of moving cells in each doubling from the heterokaryotic to the homokaryotic group based on sorting probabilities.

For cells with a greater number of nuclei, more-complex mathematical models apply (10, 25, 44). The model of Chen and coworkers can be used to calculate the number of generations necessary for “fixation” of the homokaryotic genotype. Fixation is defined as the number of generations required to reach 99% of the maximum attainable fraction of the population (10). The proportion of the population that are homokaryotic mutants at a given generation (qt) is equal to q0 − 3p0q0 (1 − 1/N)t, where p0 and q0 are the initial proportions of parental and mutant nuclei, respectively, in the transformed cell, N is the number of nuclei in the cell prior to budding, and t is the number of generations. One outcome of this model is that when t equals ∞, qt equals q0, and the maximum fraction of mutant homokaryons in the population is equal to the fraction of mutant nuclei in the initial transformed cell (Table 5). Once this predicted maximum is determined, the formula can be used to calculate the number of generations, t, to reach 99% of that maximum. Table 5 shows the results of calculations performed for a single mutant nucleus in cells with four, six, or eight total nuclei and demonstrates another property of the mathematical analysis, which is that the number of generations to fixation is roughly equal to 10 times the number of nuclei per bud (e.g., ∼20 generations at 2 nuclei per bud).

The preceding analysis suggests that it should be possible to generate a colony that is mostly homokaryotic in 20 generations. But the example chosen, of yeast cells with four nuclei and buds with two, simplifies the more complex numbers found for growing B. dermatitidis yeast. How does the presence of yeast cells with as many as eight nuclei affect the calculation? For yeast with more nuclei per cell, it will take more generations to obtain the same proportion of homokaryotic cells (Table 5). However, the number of generations may be lessened due to the fraction of cells that inherit a single nucleus. If 10% of the cells in each generation receive a single nucleus (1.8t kinetics), the cumulative effect is an 88% homokaryotic population in 20 generations, independent of other sorting effects. If, after nuclear division, sister nuclei preferentially migrate to a bud (perhaps determined by location in the cell), it would be functionally equivalent to a single nucleus migrating to a bud and would decrease the number of generations needed to fix the homokaryotic states. A combination of these effects could explain the experimental outcome of homokaryon production following transformation. At present, we cannot monitor individual nuclei during budding to answer specific questions on nuclear-sorting mechanisms. In future experiments we could fluorescently label nuclei to accomplish this goal (35).

Production of homokaryotic progeny is one of the keys to using A. tumefaciens T-DNA as an insertional mutagen to obtain recessive mutations in multinucleate B. dermatitidis. Together with transformation frequencies in the useful range and single sites of T-DNA insertion, these results fulfill the important criteria necessary for an efficient system of mutagenesis and a means for the subsequent cloning of the mutated genes in B. dermatitidis and H. capsulatum.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the U.S. Public Health Service and the American Lung Association and by a Burroughs Wellcome Scholar Award to B.S.K.

We are indebted to Jon Woods for H. capsulatum strains and plasmids and for advice concerning UV mutagenesis and uracil auxotroph isolation. We thank Chris Powell at the Wisconsin State Laboratory of Hygiene for B. dermatitidis and H. capsulatum strains. We thank Rujin Chen, Kanok Boonsirichai, and Bob Gordon for help with photography and graphics, Colin Kealey for technical assistance with plasmid construction, Patrick Masson for valuable discussions of the experimental results, and Gwynneth Coogan for assistance with mathematical analyses.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abuodeh, R. O., M. J. Orbach, M. A. Mandel, A. Das, and J. N. Galgiani. 2000. Genetic transformation of Coccidioides immitis facilitated by Agrobacterium tumefaciens. J. Infect. Dis. 181:2106-2110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baumgardner, D. J., and D. P. Paretsky. 1999. The in vitro isolation of Blastomyces dermatitidis from a woodpile in north central Wisconsin, USA. Med. Mycol. 37:163-168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beijersbergen, A., A. den Dulk-Ras, R. A. Schilperoort, and P. J. J. Hooykaas. 1992. Conjugative transfer by the virulence system of Agrobacterium tumefaciens. Science 256:1324-1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bevan, M. 1984. Binary Agrobacterium vectors for plant transformation. Nucleic Acids Res. 12:8711-8721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brandhorst, T. T., P. J. Rooney, T. D. Sullivan, and B. S. Klein. 2002. Using new genetic tools to study the pathogenesis of Blastomyces dermatitidis. Trends Microbiol. 10:25-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brandhorst, T. T., M. Wüthrich, T. Warner, and B. Klein. 1999. Targeted gene disruption reveals an adhesin indispensable for pathogenicity of Blastomyces dermatitidis. J. Exp. Med. 189:1207-1216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bundock, P., A. den Dulk-Ras, A. Beijersbergen, and P. J. Hooykaas. 1995. Trans-kingdom T-DNA transfer from Agrobacterium tumefaciens to Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J. 14:3206-3214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carr, J., and G. Shearer. 1998. Genome size, complexity, and ploidy of the pathogenic fungus Histoplasma capsulatum. J. Bacteriol. 180:6697-6703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Causey, W. A., and G. D. Campbell. 1992. Clinical aspects of blastomycosis, p. 165-188. In Y. Al-Doory and A. F. DiSalvo (ed.), Blastomycosis. Plenum Publishing, New York, N.Y.

- 10.Chen, K., S. G. Wildman, and H. H. Smith. 1977. Chloroplast DNA distribution in parasexual hybrids as shown by polypeptide composition of fraction I protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 74:5109-5112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clemons, K. V., S. M. Hurley, L. G. Treat-Clemons, and D. A. Stevens. 1991. Variable colonial phenotypic expression and comparison to nuclei number in Blastomyces dermatitidis. J. Med, Vet. Mycol. 29:156-178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Groot, M. J., P. Bundock, P. J. Hooykaas, and A. G. Beijersbergen. 1998. Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transformation of filamentous fungi. Nat. Biotechnol. 16:839-842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DeLamater, E. D. 1948. The nuclear cytology of Blastomyces dermatitidis. Mycologia 40:430-444. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.den Dulk-Ras, A., and P. J. J. Hooykaas. 1995. Electroporation of Agrobacterium tumefaciens. Methods Mol. Biol. 55:63-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fincham, J. R. S. 1989. Transformation in Fungi. Microbiol. Rev. 53:148-170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Finkel-Jimenez, B., M. Wüthrich, T. Brandhorst, and B. S. Klein. 2001. The WI-1 adhesin blocks phagocyte TNF-α production, imparting pathogenicity on Blastomyces dermatitidis. J. Immunol. 166:2665-2673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heath, J. D., T. C. Charles, and E. W. Nester. 1995. Ti plasmid and chromosomally encoded two-component systems important in plant cell transformation by Agrobacterium species, p. 367-385. In J. A. Hoch and T. J. Silhavy (ed.), Two-component signal transduction. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 18.Hogan, L. H., and B. S. Klein. 1997. Transforming DNA integrates at multiple sites in the dimorphic fungal pathogen Blastomyces dermatitidis. Gene 186:219-226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hogan, L. H., B. S. Klein, and S. M. Levitz. 1996. Virulence factors of medically important fungi. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 9:469-488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hooykaas, P. J. J., C. Roobol, and R. A. Schilperoort. 1979. Regulation of the transfer of the Ti plasmids of Agrobacterium tumefaciens. J. Gen. Microbiol. 110:99-109. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klein, B. S., J. M. Vergeront, R. J. Weeks, U. N. Kumar, G. Mathai, B. Varkey, L. Kaufman, R. W. Bradsher, J. F. Stoebig, and J. P. Davis. 1986. Isolation of Blastomyces dermatitidis in soil associated with a large outbreak of blastomycosis in Wisconsin. N. Engl. J. Med. 314:529-534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Klimpel, K. R., and W. E. Goldman. 1987. Isolation and characterization of spontaneous avirulent variants of Histoplasma capsulatum. Infect. Immun. 55:528-533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krysan, P. J., J. C. Young, and M. R. Sussman. 1999. T-DNA as an insertional mutagen in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 11:2283-2290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Magrini, V., and W. E. Goldman. 2001. Molecular mycology: a genetic toolbox for Histoplasma capsulatum. Trends Microbiol. 9:541-546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Michaelis, P. 1967. The investigation of plasmone segregation by the pattern-analysis. Nucleus 10:1-14. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Patel, J. B., J. W. Batanghari, and W. E. Goldman. 1998. Probing the yeast phase-specific expression of the CBP1 gene in Histoplasma capsulatum. J. Bacteriol. 180:1786-1792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pontecorvo, G. 1946. Genetic systems based on heterocaryosis. Cold Spring, Cold Spring Harbor Symp. Quant. Biol. 11:193-201 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Punt, P. J., R. P. Oliver, M. A. Dingemanse, P. H. Pouwels, and C. A. M. J. J. van den Hondel. 1987. Transformation of Aspergillus based on the hygromycin B resistance marker from E. coli. Gene 56:117-124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rinaldi, M. G. 1982. Use of potato flakes agar in clinical mycology. J. Clin. Microbiol. 15:1159-1160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rooney, P. J., T. D. Sullivan, and B. S. Klein. 2001. Selective expression of the virulence factor BAD1 upon morphogenesis to the pathogenic yeast form of Blastomyces dermatitidis: evidence for transcriptional regulation by a conserved mechanism. Mol. Microbiol. 39:875-889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rose, R. J., T. M. R. Thomas, and J. T. Fitter. 1990. The transfer of cytoplasmic and nuclear genomes by somatic hybridization. Aust. J. Plant Physiol. 17:303-321. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 33.Sebghati, T. S., J. T. Engle, and W. E. Goldman. 2000. Intracellular parasitism by Histoplasma capsulatum: fungal virulence and calcium dependence. Science 290:1368-1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Siebert, P. D., A. Chenchik, D. E. Kellogg, K. A. Lukyanov, and S. A. Lukyanov. 1995. An improved PCR method for walking in uncloned genomic DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 23:1087-1088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Straight, A. F., A. S. Belmont, C. C. Robinett, and A. W. Murray. 1996. GFP tagging of budding yeast chromosomes reveals that protein-protein interactions can mediate sister chromatid cohesion. Curr. Biol. 6:1599-1608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Topping, J. F., and K. Lindsey. 1995. Insertional mutagenesis and promoter trapping in plants for the isolation of genes and the study of development. Transgenic Res. 4:291-305. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Van Lijsebettens, M., B. den Boer, and J.-P. Hernalsteens. 1991. Insertional mutagenesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Sci. 80:27-37. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weising, K., and G. Kahl. 1996. Natural genetic engineering of plant cells—the molecular biology of crown gall and hairy root disease. World J. Microbiol. Bio/Technol. 12:327-351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Woods, J. P., and W. E. Goldman. 1992. In vivo generation of linear plasmids with addition of telomeric sequences by Histoplasma capsulatum. Mol. Microbiol. 6:3603-3610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Woods, J. P., E. L. Heinecke, and W. E. Goldman. 1998. Electrotransformation and expression of bacterial genes encoding hygromycin phosphotransferase and β-galactosidase in the pathogenic fungus Histoplasma capsulatum. Infect. Immun. 66:1697-1707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Woods, J. P., D. Kersulyte, W. E. Goldman, and D. E. Berg. 1993. Fast DNA isolation from Histoplasma capsulatum: methodology for arbitrary primer polymerase chain reaction-based epidemiological and clinical studies. J. Clin. Microbiol. 31:463-464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Woods, J. P., D. M. Retallack, E. L. Heinecke, and W. E. Goldman. 1998. Rare homologous gene targeting in Histoplasma capsulatum: disruption of the Ura5Hc gene by allelic replacement. J. Bacteriol. 180:5135-5143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Worsham, P. L., and W. E. Goldman. 1988. Quantitative plating of Histoplasma capsulatum without addition of conditioned medium or siderophores. J. Med. Vet. Mycol. 26:137-143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wright, S. 1952. The theoretical variance within and among subdivisions of a population that is in a steady state. Genetics 37:312-321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]