Abstract

This contribution considers entitlements and benefits in the Hungarian health care system. After a brief introduction to the organizational structure of the system the decision-making processes are discussed in detail, including the most important actors, types and pieces of legislation, formal structures, decision-making criteria, and outputs in terms of benefit catalogues. Within the two main public financing systems (social insurance and tax-funded services) there are four types of regulatory regimes: (a) traditional political decision making, (b) price negotiations, (c) updating of classification systems for payment purposes, and (d) the procedure for the inclusion of registered medicines in the scope of the social health insurance system. As an example we discuss the benefit regulations and benefit catalogues in the category of services of curative care (HC.1) of the OECD classification of health services.

Keywords: Health benefit plans, Hungary, Health services, Health priorities, National health programs

With the crisis and the collapse of the communist dictatorship Hungary witnessed the beginning of a thorough health sector reform. Replacing the tax-based financing of the state-socialist system, Hungary reverted to the earlier Bismarckian model of compulsory social insurance in 1990. New performance-based provider payment methods were introduced (capitation in primary care, fee-for-service for outpatient specialist services, and diagnosis-related groups (DRGs) in the acute inpatient care sector) together with cost-containment mechanisms to ensure that the preset budgets were not exceeded. Ownership of the majority of hospitals and other health care facilities was transferred to local governments. The vast majority of medical doctors and other health workers remained salaried public employees, with the only exception of primary care, where the bulk of family physicians work as contracted private entrepreneurs. The minimum salary for public employee physicians is determined by law, whereas the average salary in the health sector has remained among the lowest in the economy [1].

Entitlement to health care is based mainly on the participation in the social insurance scheme (with compulsory membership, opting out is not permitted), and to a few services on citizenship. The national Health Insurance Fund (HIF) provides a virtually universal population coverage with an almost comprehensive benefit package, which applies to the whole country (i.e., there are no variations by region or by payer). Nevertheless, the HIF covers only the recurrent costs of services. The owners of health care facilities, mainly local governments, are obliged to cover the capital costs of services, which usually come from general and local taxation. Tax revenues are also used for covering the deficit of the HIF [1997 Act LXXX on Those Entitled for the Services of Social Insurance and Private Pensions and the Funding of these Services, Sect. 3(2)], certain special services (e.g., public health, catastrophe medicine, experimental medical technologies, family planning and maternal care), which are financed entirely from the central government budget [1997 Act LXXXIII on the Services of Compulsory Health Insurance, Sect. 18(5)a–d, h; 1997 Act CLIV on Health, Sects. 141(2)b, 142(2)], and the copayment for certain medicines and therapeutic devices for socially disadvantaged (1993 Act III of on Social Services). In addition to informal payments to health workers, copayments for medicines and therapeutic devices constitute the most important private source of health care financing, which are almost exclusively out-of-pocket, as private health insurance is still insignificant in Hungary [1].

Decision-making processes and actors

Entitlement to publicly financed health services is regulated by various types of regulatory instruments (Table 1). These represent the decisions of various decision-making actors, with varying decision-making rules/processes and power. There is a hierarchy of regulations with the constitution on top, followed by governmental and then ministerial decrees. In the case of conflicting provisions the higher level regulation precedes the lower one, but the provisions of lower regulations are usually more detailed.

Table 1.

Main types of regulations in Hungary [1949 Act XX on the Constitution of the Republic of Hungary; 1987 Act XI on Codification; Resolution No. 1088/1994 (IX.21) on the Decision-Making Procedures of the Government; 1990 Act LXV on Local Governments]

| Type of regulation | Decision maker | Method of decision making | Consultation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Legal regulations, laws | |||

| Constitution | National Assembly | Two-thirds majority vote | Required |

| Fundamental acts | National Assembly | Two-thirds majority vote | Required |

| Acts | National Assembly | Simple majority vote | Required |

| Governmental decrees | Central government | Simple majority vote of the government or exceptionally the prime minister (one person) | Required |

| Ministerial decrees | Ministers | One person | Required |

| Local government decrees | Local government assemblies | Simple majority vote | Required |

| Rulings of the Constitutional Court | Constitutional Court | Simple majority vote | – |

| Other means of state control | |||

| Resolution | National Assembly, central government, governmental committees, local governments | According to decision maker | – |

| Order | Ministers, heads of organizations with national scope of authority | One person | – |

| Policy | National Assembly, central government, ministers, heads of national organizations | According to decision maker | Required |

| Statement of interpretation of legislations | National Assembly, central government | According to decision maker | ? |

| Announcement, communication | Ministers, heads of organizations with national scope of authority | One person | – |

The National Assembly (Parliament) and the central government (and Ministry of Health, MOH) are the key actors in national-level decision making. Parliament determines, for instance, the scope of publicly funded services, the benefit package, and the budget of the HIF. While most decisions of Parliament require a simple majority, the constitution and other fundamental acts (e.g., on local governments) can be changed only with a two-third majority vote. Passed bills are promulgated as acts, on the basis of which governmental and ministerial decrees are issued, which regulate the implementation of acts in detail [1].

In addition to acts, governmental, ministerial, and local government decrees, which represent generally valid and obligatory behavioral norms and are called “legal regulations” or “laws,” there are lower level regulations, which are categorized as “other means of state control,” such as resolutions, orders, policies, statements, and announcements (1987 Act XI on Codification, Sects. 46–56) as well as organizational operational rules and procedures of various organizations and decision-making bodies. Resolutions, for instance, can be issued by the Parliament, the government, governmental committees, local governments, and their organs to regulate the tasks of organizations controlled by them, the rules of their own operation and plans within their scope of authority, while orders can be issued by ministers and the heads of organizations with national scope of authority to regulate the activities of the organizations under their control [1987 Act XI on Codification, Sect. 46(1)].

The process of decision making and the content of the benefit basket are usually regulated at least in ministerial decrees with only a few cases, when the decision on benefits has been decentralized to other organizations (Table 2). This does not mean that the decision making has no input from a wide range of actors in the health care arena. The most important actors are as follows: (a) National Health Insurance Fund Administration (NHIFA), which administers the HIF, in particular its Department of Payment Informatics (formerly the Information Center for Health Care of MOH, (GYÓGYINFOK)) which is responsible for the provider payment and performance measurement; (b) various advisory bodies and organizations of the MOH, including the national institutes of health and the professional colleges, which provide an expert input concerning a particular medical specialty; (c) professional organizations (e.g., Hungarian Medical Chamber, HMC; Hungarian Chamber of Pharmacists, HCP), unions, and provider and patient associations [1].

Table 2.

Regulations of entitlements and benefits in Hungary

| Regulation (type according to Table 1) | What is regulated? | C/P |

|---|---|---|

| Act XX of 1949 (1) | Right to health | C |

| Act CLIV of 1997 (3) | Right to health services; scope and broad content of health services | C |

| Act LXXX of 1997 (3) | Participation in and contribution to the social insurance scheme (who is covered) | – |

| Act LXXXIII of 1997 (3) | Framework for benefits of social insurance | C, P |

| Government Decree No. No. 217/1997. (XII. 1 Korm (4) | Executive order of Act LXXIII of 1997 | P, C |

| Decree No. 46/1997. (XII. 17) NM of the Minister of Welfare (5) | Services excluded from public financing | C |

| Government Decree No. 284/1997 (XII. 23) Korm (4) | Copayments; exclusions (full fee) | C |

| Act XCIII of 1993 (3) | Occupational health services | C |

| Government Decree No. 89/1995. (VII. 14) Korm (4) | Occupational health services | C |

| Decree No. 27/1995. (VII. 25) NM of the Minister of Welfare (5) | Occupational health services | C |

| Decree No. 5/2004. (XI. 9) EüM of the Minister of Health (5) | Benefit catalogue of balneotherapy | C |

| Decree No. 20/1995. (VI. 17) NM of the Minister of Welfare (5) | Benefit catalogue of treatment in sanatoria | C |

| Decree No. 48/1997. (XII. 17) NM of the Minister of Welfare (5) | Benefit catalogue of dental care | C |

| Decree No. 49/1997. (XII. 17) NM of the Minister of Welfare (5) | Benefit catalogue of infertility treatments | C |

| Decree No. 47/1997. (XII. 17) NM of the Minister of Welfare (5) | Eligibility for free breast milk | C |

| Decree No. 50/1997. (XII. 17) NM of the Minister of Welfare (5) | Eligibility for patient transportation | C |

| Decree No. 51/1997. (XII. 18) NM of Minister of Welfare (5) | Benefit catalogue of screening | C |

| Decree No. 56/2003. (IX. 19) ESzCsM of the Minister of Health, Social and Family Affairs (5) | Benefit catalogue of balneotherapy | C |

| Decree No. 19/2003. (IV. 29) ESzCsM of the Minister of Health, Social and Family Affairs (5) | Benefit catalogue of medical aids and prostheses (therapeutic devices) | C |

| Government Decree No. 43/1999. (III. 3) Korm (Annex 8) (4) | Benefit catalogue of chronic care | C |

| Decree No. 9/1993. (IV. 2) NM of the Minister of Welfare (5) | Benefit catalogue of outpatient specialist services; acute inpatient care; dental care; day cases of curative care; dialysis; chronic outpatient care; | C |

| Decree No. 1/2003. (I. 21) ESzCsM of the Minister of Health, Social and Family Affairs (valid until 1 July 2005 then NHIFA announcement) (5, 12) | Benefit catalogue of medicines | C |

| Decree No. 20/1996. (VII. 26) NM of the Minister of Welfare (5) | Benefit catalogue of home care | C |

| Decree No. 49/2004. (V. 21) ESzCsM of the Minister of Health, Social and Family Affairs (5) | Tasks of MCH nurses | C |

| Decree No. 26/1997. (IX. 3) NM of the Minister of Welfare (5) | Tasks of school health services (physician, MCH, dentist, assistant) | C |

| Government decree No. 168/2004. (V. 25) Korm (4) | Regulatory regime (price negotiations for special medicines) | P |

| Decree No. 6/1998. (III. 11) NM of the Minister of Welfare (5) | Regulatory regime (payment) | P |

| Government Decree No. 112/2000. (VI. 29) Korm (4) | Regulatory regime (price negotiation) | P |

| Decree No. 32/2003. (IV. 26) ESzCsM of the Minister of Health, Social and Family Affairs (5) | Regulatory regime (medicines) | P |

| Order No. 6/2005. (Eb. K. 3) OEP of the Chief Executive Officer of the National Health Insurance Fund Administration (9) | Regulatory regime (medicines) | P |

C content regulation, P Process regulation

The 1987 Act XI on Codification explicitly requires relevant nongovernmental and interest representation organizations to be consulted in the phase of preparation of laws (Sects. 27–32).

Given that the existing benefit catalogues are almost exclusively incorporated into acts, governmental decrees and ministerial decrees, the general features of the decision-making processes (regulatory regimes) on benefits are common, as described above. While in these cases it is straightforward who makes the decision on the basis of what method, the real issue is who is consulted in what form in the preparatory phase of the decision making process, for which the acts discussed so far only provide a very general and vague guidance.

In many cases the decision support mechanisms have not yet been formalized in lower level regulations, and therefore that the process of preparation and codification is based on tradition. For instance, the need for the creation of a ministerial decree can originate from the provision of an act or governmental decree—in this case the MOH Legal Department initiates the codification process at the relevant professional department—or it can be initiated internally or by an external actor/stakeholder. Although each department must work on the basis of specific regulations on issue handling, in what cases, who is to be consulted, and how are usually not specified in these regulations but passed from one civil servant on the other (Zs. Kovácsy, personal communication, 2005).

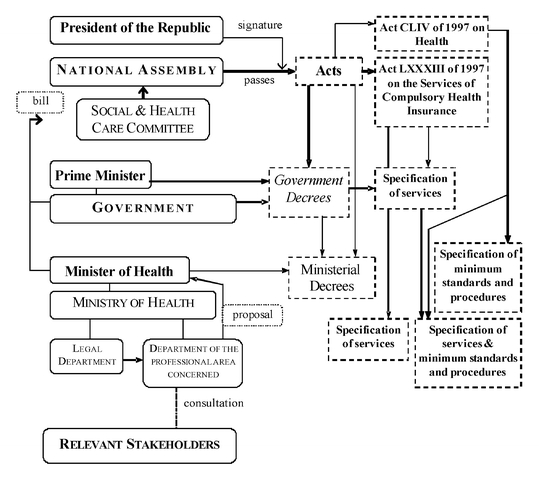

This traditional regulatory regime is the most commonly used decision-making mechanism regarding entitlements and benefits (Fig. 1). The two key acts in the center of the definition of the benefit package are 1997 Act CLIV on Health and 1997 Act LXXXIII on the Services of Compulsory Health Insurance. These acts define only a general framework in which both exclusions and inclusions are usually stipulated only at the level of broad functional categories. According to the 1997 Act CLIV, the right to health services is unconditional only for emergency life-saving services, services, which prevent serious or permanent health damage, and for the reduction in pain and suffering (Sect. 6). Patients have a right to other health services only within the limits set by another legislation (Sect. 7). The Act states that the state is responsible for the operation of the social insurance scheme to enable the individuals to exercise their right to health, and then lists the services, which must be financed from the central government’s budget (Sects. 141, 142). The 1997 Act LXXXIII defines health services which are free of charge (Sects. 10–17), covered with copayment (Sects. 23–25), or excluded [Sect. 18(5–6)]. The starting point of the Act is that all health services are fully covered and exclusions are stipulated. In the frame of social insurance all professionally justified treatments can be used [Sect. 18(4)], but diagnostic and treatment protocols issued by the MOH can further specify the actual services for which the patients are entitled to [Sect. 19(1)]. Physicians are allowed not to adhere to the protocols if the deviation is justified by the status of the patient and by therapeutic considerations. It must be noted, however, that broad functional areas are also listed (i.e., there is a scope for implicit exclusions) in the Act in three main categories: (a) services for the prevention and early detection of diseases (Sect. 10), (b) curative services, including family physician services, dental care, outpatient specialist, and inpatient care (Sects. 11–14), and (c) other services including deliveries, medical rehabilitation, patient transport and emergency ambulance services (Sects. 15–17, 22).

Fig. 1.

Traditional regulatory regime for entitlements and benefits in Hungary

These laws were passed by Parliament with a simple majority vote but are not updated or modified on a regular basis. Their modification can be initiated by the government (Minister of Health), the President of the Republic, Members of Parliament, Parliamentary Committees, or other stakeholders through these actors [Resolution No. 46/1994 (IX. 30) OGY of the National Assembly].

The above acts contain a large number of clauses, which call the government, the Minister of Health, or both of them to further specify certain functional areas. There are two main types of ministerial decrees. The 1997 Act CLIV calls on the Minister of Health to regulate the professional requirements, including minimum standards and procedures of certain service categories, and these decrees may include provisions related to the benefit package. For instance, these types of ministerial decrees can specify the tasks which must be fulfilled in the framework of a particular service (e.g., school health services Decree No. 26/1997 (IX. 3) NM of the Minister of Welfare on School Health Services) and what service can be ordered for what patients’ conditions (e.g., rehabilitative treatments in sanatoria Decree No. 20/1995 (VI. 17) NM of the Minister of Welfare on the Treatment in Sanatoria in the Frame of Medical Rehabilitation) and define who is allowed to provide specific services [e.g., home care; Decree No. 20/1996 (VII. 26) NM of the Minister Welfare on Home Care)].

On the other hand, the 1997 Act LXXXIII authorizes ministerial (and governmental) decrees to specify entitlements and benefits within a particular service category [e.g., dental care; Decree No. 48/1997 (XII. 17) NM of the Minister of Dental Services which Can Be Utilized in the Frame of the Compulsory Health Insurance]. In certain cases it is not the service concerned specified but the criteria of eligibility [e.g., the supply of breast milk; Decree No. 47/1997 (XII. 17) NM of the Minister of Welfare on the Supply of Breast Milk in the Frame of the Compulsory Health Insurance]. The updating of these decrees is made on an ad hoc basis as the need arises. Benefits are uniform throughout the country and explicitly defined, although services are usually not detailed.

Nevertheless, there are certain areas, such as pharmaceuticals and therapeutic devices, where various factors such as the presence of powerful suppliers (manufacturers of medical goods) have led to more formalized decision making. These developments received a new impetus in Hungary as a result of the country’s integration into the European Union, as the requirements of EU directives, for instance, in the case of pharmaceuticals, have had to be incorporated into Hungarian regulations. The decision-making process for the inclusion of a particular medicine in the benefit package of the social insurance scheme has been regulated down to the details of decision-making criteria.

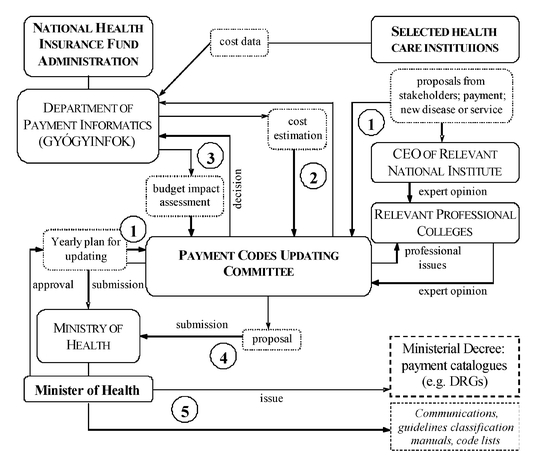

Furthermore, the introduction of new payment mechanisms created indirect means of defining benefits through the classification of cases and services for the purpose of provider reimbursement (Fig. 2). In the case of outpatient care there is a list of services with the World Health Organization International Classification of Procedures in Medicine (ICPM) codes and point values, while acute inpatient cases are categorized into one of the 786 DRGs on the basis of the diagnosis (coded on the basis of the 10th edition of the International Classification of Diseases) and the procedures performed [Decree No. 9/1993 (IV. 2) NM of the Minister of Welfare of the Social Insurance Financing of Specialist Services]. While the 1997 Act LXXXIII of declares that all professionally justified curative services are included in compulsory social health insurance financing, there is no incentive for the providers to provide services which are not reimbursed. Therefore these classification systems can be regarded as indirect benefit catalogues, with the updating procedure being their indirect modification. Since the introduction of the new payment mechanisms they have been regularly updated and the process of instituting changes has been formalized since 1998 [Decree No. 6/1998 (III. 11) NM of the Minister of Welfare on the Regulation of Updating Professional Classification Systems and Financing Parameters Used in Health Care]. The updating process includes the modification and extension of the two fundamental classification systems as well as the various payment catalogues. The extension of the ICPM has special relevance for the benefit package, since those health care interventions, which are not listed in the Hungarian version of the ICPM have been excluded from public financing (1997 Act LXXXIII on the Services of Compulsory Health Insurance).

Fig. 2.

Updated Classification Systems for Payment Purposes. [Decree No. 6/1998. (III. 11) NM of the Minister of Welfare; Procedure of the Payment Codes Updating Committee]

The key actors in the process are the GYÓGYINFOK and the so-called Payment Codes Updating Committee (PCUC), which is an advisory body of the minister of health [Decree No. 6/1998 (III. 11) NM of the Minister of Welfare on the Regulation of Updating Professional Classification Systems and Financing Parameters Used in Health Care]. The former is responsible for preparing decision support documents, including the collection and the analysis of the necessary financing data, while the PCUC makes the decisions formulated as proposals, guided by the criteria of public health impact and of the efficient allocation of resources [Procedure of the Payment Codes Updating Committee (Working Committee), December 2003, Sect. 2.5]. The ultimate decisions rest with the MOH. The list of outpatient specialist services, DRGs, day cases of curative care, chronic care services, and the various forms of dialysis (as well as their modifications) are always issued as ministerial decrees. Various announcements, communications, and guidelines are also published to promote the lawful use of payment catalogues [Decree No. 6/1998 (III. 11) NM of the Minister of Welfare on the Regulation of Updating Professional Classification Systems and Financing Parameters Used in Health Care Sects. 2(2–4), 7(1)].

The PCUC has 15 permanent members, delegated by the MOH (2), CEO of the NHIFA (2), GYÓGYINFOK (2), Hungarian Hospital Association (2), and HMC (1), while the Minister of Health appoints six medical experts and the head of the PCUC [Procedure of the Payment Codes Updating Committee (Working Committee), December 2003, Sect. 3]. The committee prepares its procedure, a yearly workplan and a methodological document as the basis of the updating process [Decree No. 6/1998 (III. 11) NM of the Minister of Welfare on the Regulation of Updating Professional Classification Systems and Financing Parameters Used in Health Care Sect. 5(4)].

The updating process can be initiated in two ways. Regular updates are planned in the workplan of PCUC, while all the relevant stakeholders are allowed to ask for unscheduled updates which must then be evaluated and answered within 30 days [Decree No. 6/1998 (III. 11) NM of the Minister of Welfare on the Regulation of Updating Professional Classification Systems and Financing Parameters Used in Health Care, Sect. 1(2)]; Procedure of the Payment Codes Updating Committee (Working Committee), December 2003, Sect. 2.4]. First, the latter proposals must be submitted to the head of the relevant national institute or directly to the Committee if there is no national institute concerned. The relevant professional college(s) then provides an expert opinion, and the GYÓGYINFOK then prepares a cost estimation and budget impact analysis usually on the basis of data provided by a sample of health care institutions. The PCUC has at least one meeting per month, whose proceedings are to be submitted to the MOH in the form of a proposal for changes at least once in a year [Decree No. 6/1998 (III. 11) NM of the Minister of Welfare on the Regulation of Updating Professional Classification Systems and Financing Parameters Used in Health Care, Sect. 5(6–7); Procedure of the Payment Codes Updating Committee (Working Committee), December 2003, Sect. 4.4].

In summary, there are four main regulatory regimes for the definition and modification of entitlements and benefits: (a) the traditional decision-making process, guided by the general rules of codification with less formalized preparatory phase, for services such as primary care and home care, (b) formalized as “price negotiations” for therapeutic devices and balneotherapy, (c) formalized as the “procedure for the inclusion of registered medicines in the scope of the social health insurance system” in line with the provisions of Council Directive 89/105/EEC (21 December 1988), and (d) formalized as the “procedure of updating professional classification systems and payment parameters” for outpatient specialist and inpatient care services.

As a result of the various regulatory regimes, universal benefit catalogues exist for almost all service areas.

Entitlements and benefits: services of curative care

Table 3 summarizes entitlements and benefits in the category of services of curative care (HC.1) of the International Classification for Health Accounts (ICHA) taxonomy [2].

Table 3.

Entitlements and benefits: services of curative care (HC.1)

| HC | Functional category | Regulatory regimea | Benefit catalogue (regulation no. from Table 2, method of classification, date passed, last updateda), taxonomy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.1 | Inpatient curative care | Updating of classification systems for payment purposes (4) | ||

| Acute inpatient care–somatic, intensive care, mental special area: transplantation | 21, Annex 3 (and Annex 8 for high cost high tech interventions; Annex 10 for course-type treatments); itemized by case (linked to diagnosis and therapy); 2 April 1993, 6 August 2004. 26 main groups (major diagnostic categories), altogether with 786 items (DRGs) |

|||

| 1.2 | Day cases of curative care | |||

| Specialist outpatient care—day surgery | 21, Annex 9; itemized by service; 2 April 1993, 6 August 2004. 227 items in two lists: (a) 194 elective surgical procedures (Sect. I), (b) 33 other (“clinical”) interventions (Sect. III) |

|||

| Special area: hemodialysis | 21, Annex 11; itemized by service; 2 April 1993, 2 March 2001. 6 items: (a) hemodialysis, hemofiltration, hemodiafiltration; (b) same for patients under 18 years old; (c) peritoneal dialysis, (d) hemoperfusion, (e) hemodialysis with reusable dialysator, (f) mobile treatment |

|||

| 1.3 | Outpatient care | |||

| 1.3.1 | Basic medical and diagnostic services | |||

| (Curative) primary care | Traditional (2, 4) | – | ||

| 1.3.2 | Outpatient dental care | |||

| Dental prophylaxis, care, surgery | Traditional (2, 4) | 13; itemized by service; 17 December 1997, 1 November 2001. 3 main groups: (a) dental screening, with 7 items in three subgroups; (b) dental emergency services with 10 items; (c) dental primary and secondary care, defined as the payment list, detailed in a separate decree (no. 21) |

||

| Updating of classification systems for payment purposes (4) | 21, Annex 12; itemized by service; 2 April 1993, 11 March 2003. 125 items in 10 groups: (a) examinations, documentations, 9; (b) prevention, 5; (c) radiography, 5; (d) anesthesia and drug prescription, 5; (e) tooth preserving services and endodontia, 12; (f) oral diseases and parodontology, 11; (g) dental surgery, 24; (h) dental prosthetics, 26; (i) child, school, and youth dental services, 13; (j) orthodontia, 15 |

|||

| 1.3.3 | All other specialized health care | |||

| Specialist outpatient care–somatic | Updating of classification systems for payment purposes (4) | 21, Annex 2; itemized by service; 2 April 1993, 27 August 2004. List contains 3,166 (and together with the dispensary specific services 3,204) items (based on the 1978 ICPM of WHO) |

||

| Specialist outpatient care–mental; special area: psychoanalysis, -therapy | 21, Annex 15; itemized by service; 11 May 2004. Altogether 120 items (82 items overlap with Annex 2) in five main groups: (a) skin and STD, 29 items; (b) oncology, 26 items; (c) pulmonology, 25 items; (d) psychiatry, 19 items; (e) addictology, 21 items |

|||

| 1.3.9 | All other outpatient curative care | |||

| Outpatient care by other professionals | Updating of payment classification systems (4) | As with 1.3.3, which are included (e.g., logopedia, physiotherapy, dietetics, optometry, acupuncture); the rest are implicitly excluded (e.g., chiropody, bioenergy treatments, iris diagnostics, hydrotherapy) | ||

| Alternative and complementary medicine | ||||

| Special area: balneotherapy and physiotherapy | Traditional (4) | 11 (definition of entitlements, regulation of prescription, utilization, and professional requirements); itemized by service; indications and contraindications; 9 November 2004. Annex 1, balneotherapy services, 10 items; Annex 4, physiotherapy services, 13 items; Annexes 5 and 6, indications and contraindications |

||

| Price negotiations (4) | 18; itemized by service; 19 September 2003. 3 groups with the same 10 items; copayment is different for spas, which have national, regional, and local qualification |

|||

| 1.4 | Services of curative home care | Traditional (4) | 23, Annex 1 (specifies professional requirements); itemized by service; 26 July 1996, 9 June 1999. 13 service categories, 22 items (includes hospice at home) |

|

a Benefit catalogues with the traditional regulatory regime are updated on an ad hoc basis, while the updating of payment lists is regular. All benefit catalogues are issued as ministerial decrees.

The general framework for these services is set by the 1997 Acts CLIV and LXXXIII, as discussed above, but all health services in this category are considered within the frame of the social insurance scheme. Although the 1997 Act LXXXIII states that all professionally justified services are included, in most cases the detailed payment catalogues imply implicit exclusions, such as most services of alternative medicine. With the exception of family physician services (primary care), there are benefit catalogues for each service category, either as a list of cases/services for payment purposes (1.1, 1.2, partly 1.3.2, 1.3.3, and partly 1.3.9) or for further specification of broad functional categories enumerated in the Act (partly 1.3.2, partly balneotherapy) or for the specification of professional requirements (1.4, partly balneotherapy).

These nationally valid benefit catalogues are the output of either the traditional decision-making process or the process of updating classification systems for payment purposes. They are issued as a ministerial decree in both cases, with the MOH being the final decision maker. Updating is ad hoc in the case of the former and regular in the case of the latter, where the preparatory phase is much more formalized and even a few decision-making criteria are defined (budget and public health impact), as discussed above.

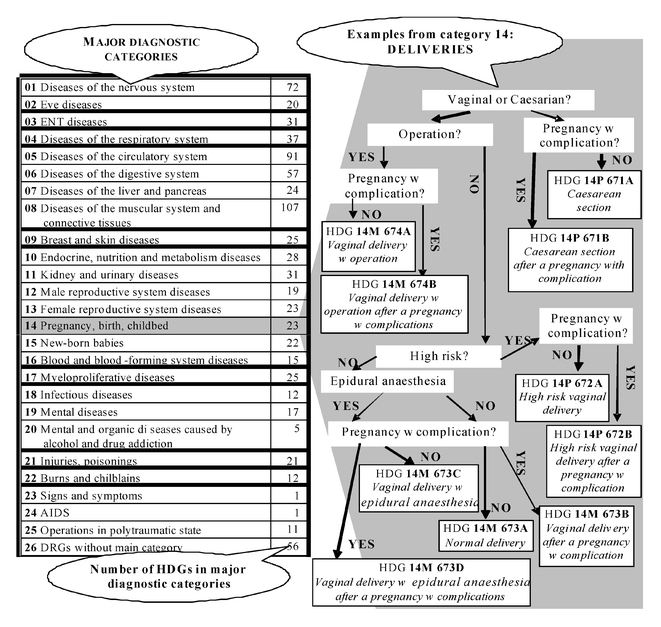

Undoubtedly the two most detailed benefit catalogues are the lists of DRGs for inpatient curative care (1.1), and the so-called WHO point, or German point system for outpatient specialist care (1.3.3, partly 1.3.9). The essence of the DRG based hospital payment is that it pays a standard fee for discharged acute hospital cases and not for any individual service items such as laboratory tests, hospital days, drugs, and procedures. The DRG system classifies cases into a manageable number of categories, which are more or less medically meaningful and in which resource use is the same or at least similar (homogeneous resource use) [3]. The DRG system was introduced countrywide in Hungary in 1993 after a pilot project that began in 1987. The DRG system in the United States was adapted to the local situation using the cost data collected [4]. The current version of the Hungarian adaptation of DRGs (homogeneous disease groups, HDGs) is 5.0, which contains 786 groups in 26 main diagnostic categories [Decree No. 9/1993 (IV. 2) NM of the Minister of Welfare of the Social Insurance Financing of Specialist Services]. The first step of classifying patients is to determine the major diagnostic category, in which the main diagnosis and/or the interventions can be a principal classification criterion, which is to be further modified by comorbidity and age. For instance there are three groups of classifying factors in the major diagnostic category 14 (pregnancy, birth and childbed): the type of pregnancy (without complications, pathological pregnancy), the type of delivery (cesarean, vaginal, vaginal with operation, vaginal with epidural anesthesia) and the conditions of delivery (high risk, other comorbidity; Fig. 3). While in principle inpatient cases are sorted into HDGs primarily on the basis of diagnosis, which leaves hospital physicians to select treatment options freely, several treatment modalities are costly enough to be a principal classification criterion.

Fig. 3.

Examples of the homogeneous disease groups in Hungary. [Decree No. 9/1993. (IV. 2) NM of the Minister of Welfare on the Social Insurance Financing of Specialist Services]

The WHO point system, however, is entirely itemized by service. It is based on the 1978 ICPM, but the original list has been modified frequently ever since it has been introduced as the basis of payment in the outpatient specialist setting. Along with the chronic outpatient care items, the current catalogue contains 3,204 service items and has been in effect since 27 August 2004. Each service has a five-digit identification code and the services are listed in numerical order, from item 110011 (first aid) to 97550 (ambulatory developmental-neurology follow-up care of infants with spina bifida) and the list closes with 12 items of “complementary” points for special transfusion (two items) for noncompliant patients who threaten or attack attending medical staff (one item), for supervision of patients after treatment (five items), for drug loading (one item), and for patients of young age (three items). The list in the ministerial decree is not structured in groups or subgroups, but it is generally service (e.g., ultrasound examinations) and organ-oriented [e.g., eye-examinations; Decree No. 9/1993 (IV. 2) NM of the Minister of Welfare of the Social Insurance Financing of Specialist Services].

Discussion

The provision of universal and comprehensive coverage was the founding principle of the previous, state-socialist health care system. The tension between the changing and increasing needs and the available resources created shortages which have not been acknowledged and explicitly dealt with. Rationing effectively occurred through queuing, implicit waiting lists, the dilution of services, and informal payments [1].

The social insurance and payment reforms have brought about little change in this respect. Successive governments have faced the chronic deficit of the HIF, but measures to balance the budget have almost exclusively targeted the revenue side of the system, and only minor modifications have been implemented in the almost comprehensive benefit package [1]. Although entitlements are in principle linked to paying the contribution, the coverage is universal in practice since entitlement is not checked by the providers [5]. Despite payment catalogues the benefit package is defined rather negatively. While services financed by the HIF should be provided according to treatment protocols issued by the MOH, no such protocols have yet come into effect.

The general opinion in Hungary is that more explicit priority setting with more exclusions or more significant copayments would not be accepted by the majority of the population, and therefore politicians are reluctant to touch the issue of priority setting in a more systematic manner. On the other hand, the financial pressure on the system is high, and indirect, implicit rationing does occur, for instance, through informal payments. It is a question of how long this schism can be uphold, especially in the light of the challenges by joining the EU.

The plan of the current government is to revise entitlements to health care by expanding the scope of services to all emergency care for which all citizens are eligible [6]. The rest of the health services will be provided on the basis of participation in the social insurance scheme, but it will be checked whether the patient is in fact entitled to services. Furthermore, the government plans to revitalize the system of treatment protocols, which is obviously a means to exclude certain interventions. It is not yet known whether this is only a first step towards a more explicit priority setting, or whether the benefit package remains essentially unchanged.

Acknowledgements

The results presented here are based on the project “Health Benefits and Service Costs in Europe–HealthBASKET” which is funded by the European Commission within the Sixth Framework Research Programme (grant no. SP21-CT-2004-501588).

References

- 1.Gaal P (2004) Health care systems in transition: Hungary. WHO Regional Office for Europe on behalf of the European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies: Copenhagen

- 2.Organisation for Economic Cooperation, Development (2000) A system of health accounts. Paris: OECD

- 3.Smith H, Fottler M (1985) Prospective payment. Aspen: Rockville

- 4.Nagy J (1996) A HBCS alapú kórházi teljesítmény elszámolási rendszer felépítése és három eves alkalmazásának tapasztalatai [The Structure of DRG Based Hospital Financing System and the Experiences of Three Years in Operation]. GYÓGYINFOK: Szekszárd

- 5.Sinkó E (2005) Közhiteles nyilvántartások az egészségügyben II. IME 4:44–8

- 6.Government of Hungary (2005) 100 lépés: Egészségügy [One hundred steps: Health care].http://www.magyarorszag.hu/100lepes/egeszsegugy. Accessed on 24/08/2005