Abstract

Lymphodepletion followed by adoptive cell transfer (ACT) of autologous, tumor-reactive T cells boosts antitumor immunotherapeutic activity in mouse and in humans. In the most recent clinical trials, lymphodepletion together with ACT has an objective response rate of 50% in patients with solid metastatic tumors. The mechanisms underlying this recent advance in cancer immunotherapy are beginning to be elucidated and include: the elimination of cellular cytokine ‘sinks’ for homeostatic γC-cytokines, such as interleukin-7 (IL-7), IL-15 and possibly IL-21, which activate and expand tumor-reactive T cells; the impairment of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T (Treg) cells that suppress tumor-reactive T cells; and the induction of tumor apoptosis and necrosis in conjunction with antigen-presenting cell activation. Knowledge of these factors could be exploited therapeutically to improve the in vivo function of adoptively transferred, tumor-reactive T cells for the treatment of cancer.

Introduction

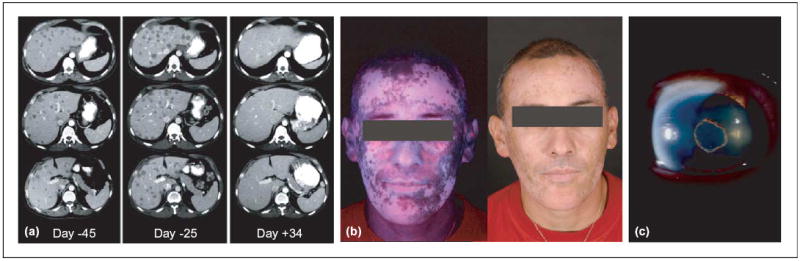

Adoptive cell transfer (ACT) of large numbers of autologous tumor-reactive T cells into a tumor-bearing host represents a promising therapy for the treatment of metastatic cancer in humans [1]. This exciting therapy uses the rapid ex vivo expansion of tumor-infiltrating or -reactive lymphocytes (TILs), which are subsequently transferred in conjunction with the administration of a high-dose of a stimulatory cytokine, in particular interleukin-2 (IL-2). Although other forms of immunotherapy, such as tumor-antigen (Ag) vaccination or the administration of immune-stimulating cytokines alone, are capable of raising tumor-reactive T cells in vivo, they do not reliably induce the regression of large established solid tumors (reviewed in Ref. [2]). ACT is capable of mediating tumor regression [3–6], however, these effects are even more pronounced in the absence of host lymphocytes [7,8]. This approach has resulted in the most consistent and dramatic clinical responses observed in the treatment of metastatic cancer [7] (Figure 1a).

Figure 1.

Potentiation of immune response to non-mutated shared self-antigens and tumor antigens by lymphodepletion. Following adoptive cell transfer therapy with tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs), in the setting of chemotherapy-mediated lymphoablation: (a) Computed tomography (CT) scan of liver metastases in a melanoma patient. Metastatic lesions progressed rapidly before the treatment (from day −45 to day −25) then regressed dramatically after adoptive T-cell transfer (day +34). (b) Extensive destruction of normal melanocytes (vitiligo) in a patient who experienced a remarkable clinical response. (c) Anterior uveitis (inflammation of the eye) in a patient who exhibited >99% tumor reduction Photographs courtesy of S.A. Rosenberg.

These clinical responses are associated with autoimmune manifestations in sites that express shared melanocyte or melanoma Ags, such as the skin, in the form of vitiligo. With lymphodepletion, we have also observed melanocyte destruction at immune privileged sites, such as the eye (Figure 1b,c). Although skin-de-pigmentation has been previously associated with immunotherapies, inflammation of the anterior segment of the eye has not been previously observed, and might be indicative of a more potent activating stimulus. Fortunately, these eye manifestations are treatable with local steroids, which do not detract from the antitumor immune destruction.

The specific mechanisms that contribute to this enhanced state of immunity remain poorly understood. Recent insights in two rapidly expanding fields, the cytokine-mediated homeostasis of mature lymphocytes by γC-cytokines, such as IL-7, IL-15 and IL-21, and the control of autoreactive T cells by CD4+CD25+ regulatory T (Treg) cells, provide the foundation for what might be occurring after lymphodepletion. The removal of lymphocytes that compete for homeostatic cytokines or suppress tumor-reactive T cells might contribute to the enhancement and subsequent tumor destruction by the adoptively transferred T cells. The less described role of antigen-presenting cell (APC) activation by lymphodepletion might also have a role in T-cell activation. Knowledge of these factors presents the potential for therapeutic exploitation in the treatment of metastatic cancer in humans.

A link between lymphodepletion and augmented immune function

It has long been observed that transfer of small numbers of T cells into lymphopenic hosts results in T-cell expansion, a process described as homeostatic proliferation [9–16]. As the T cells proliferate, they assume an Ag-experienced or memory phenotype, which is indicated by upregulation of CD44, Ly6C and CD122 (IL-2–IL-15Rβ) [12,15]. This T-cell expansion and acquisition of a memory phenotype is also associated with enhanced effector functions, determined by ex vivo analysis of interferon-γ (IFN-γ) release and cytolysis [12,14,15]. In a recent autoimmunity study, King et al. showed that the inherent lymphopenia in non-obese diabetic (NOD) mice and increased expression of IL-21 drives the homeostatic expansion of autoreactive cells, precipitating self-tissue destruction [17]. Furthermore, adoptive transfer of naïve lymphocytic choriomenigitis virus (LCMV)-specific CD8+ T-cell receptor (TCR) transgenic splenocytes into LCMV-infected lymphodepleted, but not replete, hosts rapidly reduced viral titers to below detection limits [13]. Analogous results have also been observed in another model, based on the 2C T-cell receptor (TCR) transgenic model. 2C TCR transgenic T cells are specific for an Ld-restricted α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase epitope or the SIYRYYGL peptide in the context MHC I H2-Kb. These cells expand homeostatically in Rag−/− mice and specifically treat tumors, at a comparable level to the T cells derived from Ag-specific vaccination [15]. Dummer et al. observed that adoptive transfer of a polyclonal population of T cells into a Rag−/− or sublethally irradiated mouse specifically inhibits tumor growth [18].

It is interesting to note that in these models, lymphopenic-induced activation and pathogen or tumor clearance are generated in the absence of Ag-specific vaccination. Ag-specific CD8+ T cells are required for pathogen or tumor clearance, and the need for subsequent immunization might be negated [19,20]. These model Ags have given us great insight into homeostatic proliferation but focus primarily on Ags that are of a foreign origin. Perhaps using a self- or tumor-antigen might provide a setting that is more analogous to the human condition. A recently described tumor model, Pmel-1, which uses a transgenic CD8+ T-cell specific for both the native and altered peptide ligand of the melanocyte and melanoma differentiation molecule gp100, might enable us to better model unmutated self-antigens in the clinical setting [5,21].

Evidence for the presence of homeostatic cellular cytokine ‘sinks’

The proliferation of adoptively transferred Tcells in lymphopenic hosts can be reduced in a dose-dependent manner, either by increasing the total number of Ag-specific cells transfused or by co-transferring an ‘irrelevant’ population of Tcells [9,15,16,22]. Host CD8+ Tcells have a dominant role in modulating both donor CD8+ and CD4+ T-cell expansion in lymphopenic hosts [16]. In the same study, host CD4+ cells inhibited donor CD4+, and to a lesser extent CD8+ T-cell proliferation.

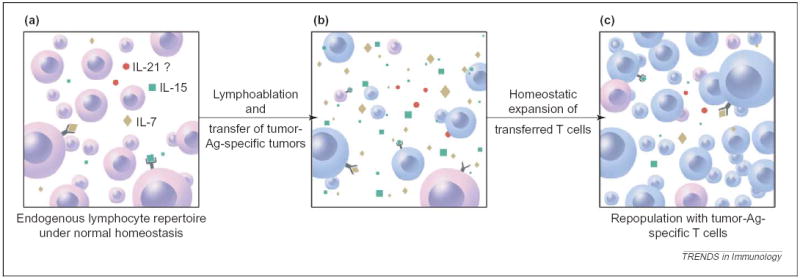

The ability of the host to inhibit the proliferation of adoptively transferred T cells could be the result of physical contact between T cells or competition between T cells for self-MHC–peptide complexes and supportive homeostatic cytokines (Figure 2). Naïve T-cell proliferation is a result of self-MHC–peptide interactions in a lymphopenic environment (reviewed in Ref. [23]), whereas memory T cells proliferate independently of these interactions [12,16]. This is suggestive of Ag-independent activation, a notion that has recently received a great deal of attention. Some studies have focused on the role of host-derived IL-7 and IL-15, and more recently IL-21, γC cytokines known to stimulate and induce the proliferation of mature T cells [24–26].

Figure 2.

Removal of consumptive cytokine ‘sink’ by lymphoablation. (a) Under normal homeostasis, a smaller quantity of cytokines [IL-7 (yellow), IL-15 (green) and possibly IL-21 (red)] are available owing to consumption by the endogenous lymphocyte population. (b) After lymphodepletion preconditioning by chemotherapy or irradiation, the consumptive cellular cytokine ‘sinks’ are removed, enabling the adoptively transferred T cells a less competitive environment and greater access to IL-7, IL-15 and IL-21. (c) This is followed by preferential homeostatic expansion and re-population of the peripheral lymphoid compartments with the adoptively transferred, tumor-reactive T cells.

In transgenic mice that overexpress IL-7 or IL-15, there is a substantial increase in the absolute number of T cells [27,28]. This increase is driven largely by the expansion of CD8+CD44high memory Tcells. Exogenous administration of IL-15 or induction of host expression of IL-15 in wildtype mice by reagents, such as poly I:C, lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and type I-IFNs, causes a selective increase in the proliferation of CD8+CD44high T cells in vivo [29–31]. Exogenous administration of IL-7 to mice enhances T-cell number and function [32,33] and, in both intact and immunodeficient non-human primates, causes a considerable yet reversible increase in the circulating levels of naïve and Ag-experienced CD4+ and CD8+ T cells [34]. Although similar studies have yet to be conducted in humans, there is evidence to support an inverse correlation between serum levels of IL-7 and the severity of lymphopenia caused by conditions, such as AIDS and cytotoxic drug therapy (reviewed in Ref. [35]). Currently, there are no data available that evaluate the in vivo effects of IL-15 in primates or humans.

Studies that examine mice deficient in IL-7 or IL-15 have demonstrated that these cytokines have a supportive role in the survival and/or proliferation of adoptively transferred T cells in lymphodepleted hosts [36–40]. The absence of IL-7 inhibits naïve CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell homeostatic proliferation and survival in a lymphopenic environment. The proliferation of donor cells in these IL-7−/− hosts is rescued by the administration of exogenous IL-7 [36,41]. IL-7 has a significant role in naïve T-cell homeostatic proliferation but has little impact on memory T-cell expansion and survival in a lymphopenic host [37,38]. In contrast to IL-7, IL-15 does not contribute to naïve T-cell homeostasis but does have a pivotal role in memory CD8+ T-cell proliferation and durability [38]. The homeostatic expansion of memory CD8+ T cells does not rely solely on IL-7, however, these cells do constitutively express high levels of both IL-7Rα (CD127) and the components of the IL-15–IL-2 heterodimeric complex, IL-2–IL-15Rβ(CD122) and γc (CD132), and thus might be sensitive to IL-7 [30,38,42].

In summary, it is clear that cytokines can have a profound impact in regulating the homeostasis of T cells in both the normal and lymphopenic settings. The expression of IL-7 and IL-15 receptors on memory T cells might indicate that the administration of these cytokines could enhance both the survival and proliferation of adoptively transferred, tumor-reactive T cells in vivo. In a recently described murine tumor model [5], it appears that the long-term tumor treatment efficacy of adoptively transferred, tumor-specific CD8+ T cells is compromised in whole-body irradiated IL-15−/− but not wildtype hosts [43]. Endogenously produced IL-15 might contribute to a sustained antitumor treatment response by adoptively transferred CD8+ T cells in a lymphopenic setting. It is likely that non-tumor-specific T cells and other immune cells, such as natural killer (NK) cells, consume IL-15 in the wildtype host. Thus, there could be competition for homeostatic cytokines in the replete host. It is also important to mention the newly discovered cytokine IL-21, which shares homology with IL-2 and IL-15 and binds their common γc receptor [44,45]. This cytokine might augment the function of adoptively transferred tumor-specific CD8+ T cells [17,46] and is the subject of ongoing investigations. Many unresolved questions regarding the use of γc receptor cytokines remain to be answered (Box 1).

Box 1. Unresolved questions regarding the use of γc cytokines

Does the absence of endogenous IL-15 impair the early or late in vivo proliferation, functionality, and maintenance of adoptively transferred tumor-specific T cells, and thus their ability to mediate tumor destruction?

What influence does host-derived IL-7 alone, or in combination with IL-15, have on tumor-reactive T cells and their function?

What is the role of IL-21 in homeostatic proliferation, and does exogenous administration improve the ability of adoptive transferred tumor-specific T cells to kill tumor?

Role of regulatory cells in antitumor immunity

Naturally occurring and induced CD4+CD25+ Treg cells can potently suppress immune responses to self-Ags and foreign Ags in both humans and mice. The phenotype and function of Treg cells have been reviewed in detail elsewhere [47,48]. There are some features of Treg cells that might be of particular interest to tumor immunologists. CD4+CD25+ Treg cells express high levels of cell-surface molecules typically associated with activation; these include CD25 (IL-2Rα), glucocorticoid-induced tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-receptor (GITR) and cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated Ag-4 (CTLA-4). In addition, they also express a unique intracellular protein, Foxp3. Treg cells are completely absent in mice that are deficient in the genes encoding IL-2, IL-2Rα, IL-2Rβ and Foxp3, suggesting a crucial role for both IL-2 signaling and Foxp3 expression in Treg-cell ontogeny and survival [49–51]. The role of Treg cells in maintaining immunological tolerance to self-Ags has been illuminated, in part, through adoptive transfer experiments. A spectrum of tissue-specific autoimmune diseases, including thyroiditis, oophoritis, gastritis and inflammatory bowel disease, occurs when immunodeficient mice are transfused with T cells depleted of CD4+CD25+ cells [52,53]. The concomitant transfer of Treg cells abrogates development of these autoimmune diseases. In some models, transfer of Treg cells after the onset of disease can even be curative [54]. The close correlation between autoimmunity and tumor immunity [5,7,55–59] suggests that Treg cells have a crucial role in T-cell tolerance to tumor [60–62].

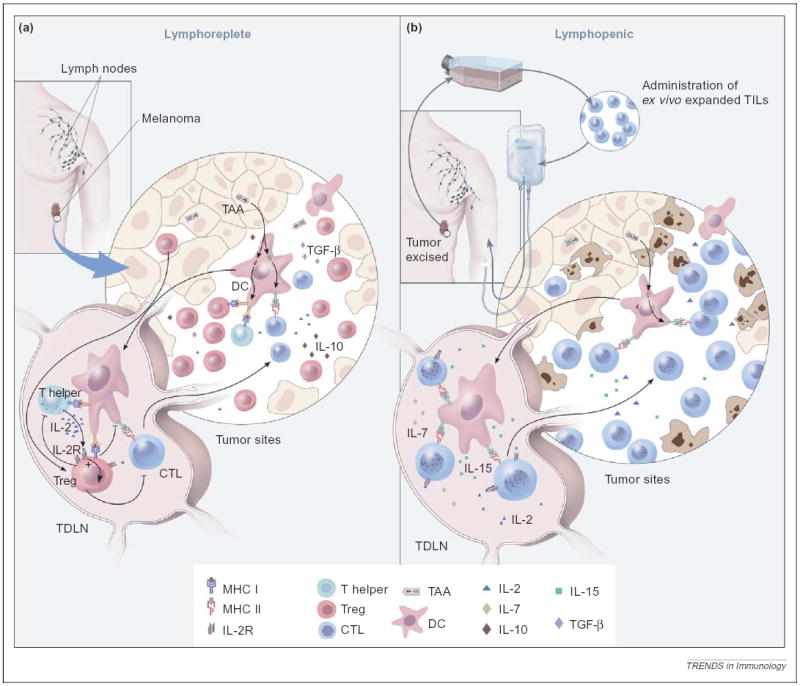

Although the significance of Treg cells in human cancers has only recently begun to be explored, many of the findings in mice could be recapitulated in humans [61,63,64]. Wang et al. recently reported on the isolation of CD4+CD25− TIL clones derived from a melanoma patient [65]. These clones displayed many of the phenotypic and functional properties associated with naturally occurring Treg cells and were antigen-specific. Another report has shown that Treg cells present in the circulation of patients vaccinated against melanoma Ags can suppress the proliferation of a polyclonal population of CD4+CD25− T cells [66], however, the Ag-specificity of these cells was not determined. Treg cells capable of suppressing the in vitro function of tumor-reactive T cells in humans has also been found in other tumors besides melanoma [67,68]. In one instance, tumor deposits taken from patients with lung cancer reportedly contained large numbers of CD4+CD25+ Treg cells capable of suppressing the proliferation of autologous TILs [68]. In contrast to these murine studies, no conclusive data link the in vivo function of tumor-reactive Treg cells and the progression of cancer in humans, although some recent evidence suggests that Treg tumor infiltration might be associated with survival of cancer patients [69]. However, removal of these regulatory elements (Box 2), perhaps in conjunction with cytokine sinks, could reverse or prevent the tolerance of adoptively transferred tumor-reactive T cells (Figure 3).

Box 2. Eradication of Tregs

Although Food and Drug Administration-approved drugs are available that can selectively deplete CD25-expressing cells in humans, including humanized anti-Tac (anti-CD25) and ONTAK™ (IL-2 conjugated to diphtheria toxin), it is currently unknown what effect these reagents might have on Treg cells as well as on activated tumor-reactive T cells.

Until a unique cell surface lineage marker capable of discriminating between Treg and activated T cells can be discovered, non-specific lymphodepletion might be the only practical approach to removing Treg cells from patients for the purpose of augmenting their in vivo immune reactivity to a tumor.

Figure 3.

Removal of the inhibitory effect of Treg cells and activation of DCs by lymphoablation. (a) Under normal homeostasis, Treg cells (red) in the tumor draining lymph node (TDLN), might exert inhibitory effects on the transferred tumor-specific T cells (blue). In addition, Treg cells might prevent CD4+ Th cells (green) from providing supportive cytokines, such as IL-2 (blue). DCs (pink) in the tumor, which cross-present tumor-associated antigens (TAAs), might induce tolerance in the absence of inflammation and in the presence of immunosuppressive cytokines, such as IL-10 (brown) and TGF-β (purple). The net outcome of these inhibitory factors could abrogate an effective antitumor response. (b) After the induction of lymphopenia, ex vivo expanded tumor-reactive TILs are adoptively transferred (blue). This preconditioning before cell transfer effectively eliminates Treg cells and other cytokine-competing cells, thus removing inhibition and freeing supportive cytokines, such as IL-2, IL-7 (yellow) and IL-15 (green). The ablative conditioning might also activate DCs that are capable of cross-presenting TAAs in the presence of danger signals. The effect of ablation is a ‘permissive’ and activating environment that augments tumor-specific T cell-induced tumor destruction.

Effects of lymphodepleting radiation and chemotherapy on APC function

Lymphodepletion before ACT uses total body irradiation (TBI) or cytotoxic drugs. Although these modalities were initially intended to deplete the lymphoid compartment of recipients, they can also facilitate the presentation of tumor antigens by triggering tumor cell death and antigen release. Subsequently, these antigens can be taken up and presented by APCs to enhance the activation of the adoptively transferred tumor-reactive cells [70].

Indirect evidence indicates that there might be other beneficial effects of lymphodepletion in our current ACT model. Irradiation and/or chemotherapy leads to activation of host cells, resulting in the release of proinflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α, IL-1 and IL-4 [71–74], and upregulation of co-stimulatory molecules, such as CD80 [75]. In a recent study, activation markers I-Ab (class II) and CD86 were upregulated on splenic DCs as early as 6 h after TBI. Furthermore, ex vivo IL-12 production was significantly higher from DCs isolated 6 h after irradiation than DCs from non-irradiated mice [76]. Consistent with this finding, serum levels of IL-12 were also increased in these mice. Elimination of competitive T cells through lymphodepletion might improve donor T-cell access to, and activation by, antigen-bearing APCs [77], although other workers have found that competition might not play an influential role [78].

In addition to enhanced APC function and availability, the preconditioning regimen can damage the integrity of mucosal barriers through radiation-induced apoptosis of the cells lining these organs. Damage inflicted on the intestinal tract might permit the translocation of bacterial products, such as LPS, into the systemic circulation[79]. LPS activates T cells in vivo [31] and might enhance the antitumor response. Thus, proinflammatory cytokines and microbial products provide crucial ‘danger signals’ for the activation and maturation of DCs, thus enhancing T cell-mediated tumor treatment.

Although initially beneficial, lymphodepletion can depress the absolute number of host APCs. As reported in several murine studies, the total number of monocytes, macrophages and DCs are only slightly reduced at 6 and 24 h but are significantly reduced 5 days after TBI [71,76]. This could be detrimental in the case of the current tumor therapy model, which requires an active vaccination for successful tumor therapy[5]. Interestingly, late clearance did not hinder the activation of the donor T cells[76]. This corroborates with several reports that demonstrate antigenic stimulation, before APC clearance, is all that is required to initiate activation and proliferation of T cells [80,81].

Therapeutic implications and future directions

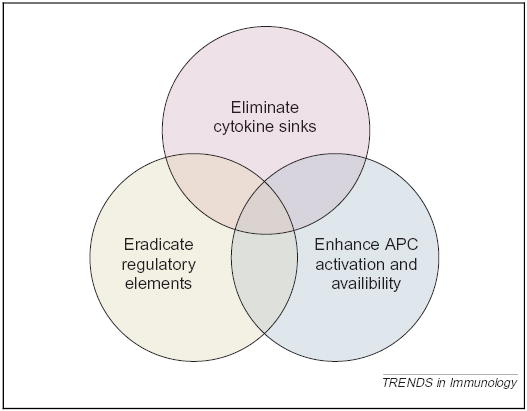

It is clear that lymphodepletion before adoptive transfer of tumor-reactive T cells into animals and humans with cancer augments in vivo function of the transferred cells and the therapeutic outcome. Increased access to the homeostatic cytokines, such as IL-7 and IL-15, through elimination of cytokine sinks, eradication of the suppressive influence of Treg cells and enhancement of APC activation and availability appear to be the underlying mechanisms involved in this paradigm (Figure 4). The mechanisms are complex, however, elucidation through the use of targeted cytokine administration, add-back of sink or suppressor elements and selective deletion or addition of APCs might explain how these mechanisms interact.

Figure 4.

An interactive model for the mechanisms underlying the impact of lymphodepletion on adoptively transferred T cells. (i) Elimination of cytokine sinks: lymphoablation, either by chemotherapy or irradiation, reduces the consumptive cytokine ‘sinks’ created by the endogenous lymphocyte repertoire, thus enabling the transferred T cells a less competitive access to homeostatic cytokines, such as IL-7 and IL-15. (ii) Eradication of regulatory elements: Treg cells, such as the CD4+CD25+ cells, that would otherwise exert an inhibitory effect on the transferred T cells are diminished in number and function after lymphoablation. (iii) Enhancement of APC activation and availability: lymphoablation, either by irradiation or chemotherapy, can induce tumor apoptosis and necrosis, resulting in uptake and presentation of tumor antigens by APCs. Furthermore, there is some evidence that suggests that after lymphodepletion, APCs become activated, thus enhancing stimulation of the adoptively transferred T cells. The transferred T cells also have less competition with irrelevant T cells for APCs, which might improve activation. These mechanisms can act independently or in synergy to augment the function of the tumor-reactive T cells.

Other modalities that mimic or enhance the positive effects of lymphodepletion could have great therapeutic potential. The exogenous administration of supportive cytokines, such as IL-2, IL-7, IL-15 or IL-21, either alone or in concert, could stimulate the adoptively transferred T cells and enhance their tumor-killing ability. Ways to selectively deplete or inhibit CD4+CD25+ Treg cells with the use of antibodies against CD25 or GITR remain the pursuit of many workers, although clear effects have been less then forthcoming. Modulation of adoptively transferred cells either through overproduction of cytokines, such as IL-7, IL-15 [43] or IL-21, or cytokine receptors, such as IL-7Rα and IL-15Rα, are currently being explored as possible means to enhance T-cell function in vivo. Reagents that stimulate host expression of IL-15 and IL-15Rα [30,31,82], including type I IFNs, CpG DNA, LPS, dsRNA and dsRNA-imitators, such as polyI:C, might enhance the functionality of adoptively transferred cells.

Finally, although IL-2 has been the preferred cytokine for the ex vivo [83] and in vivo [7,8] activation and expansion of tumor-reactive T cells, it also drives Treg proliferation and activation [84] and triggers apoptosis in activated T cells [85]. Exploration of other cytokines that can drive tumor-reactive T cells, such as IL-7, IL-15 and IL-21, might prove to be more efficacious in the activation of adoptively transferred tumor-reactive cells.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Crystal L. Mackall for critical review of the manuscript and Steven A. Rosenberg for his support of translational research at the National Cancer Institute.

References

- 1.Dudley ME, Rosenberg SA. Adoptive-cell-transfer therapy for the treatment of patients with cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:666–675. doi: 10.1038/nrc1167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rosenber SA, et al. Cancer immunotherapy: moving beyond current vaccines. Nat Med. 2004;10:909–915. doi: 10.1038/nm1100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cheever M, et al. Augmentation of the anti-tumor therapeutic efficacy of long-term cultured T lymphocytes by in vivo administration of purified interleukin 2. J Exp Med. 1982;155:968–980. doi: 10.1084/jem.155.4.968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Overwijk W, et al. gp100/pmel 17 is a murine tumor rejection antigen: induction of ‘self’-reactive, tumoricidal T cells using high-affinity, altered peptide ligand. J Exp Med. 1998;188:277–286. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.2.277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Overwijk W, et al. Tumor regression and autoimmunity after reversal of a functionally tolerant state of self-reactive CD8+ T cells. J Exp Med. 2003;198:569–580. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yee C, et al. Adoptive T cell therapy using antigen-specific CD8+ T cell clones for the treatment of patients with metastatic melanoma: in vivo persistence, migration, and antitumor effect of transferred T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:16168–16173. doi: 10.1073/pnas.242600099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dudley M, et al. Cancer regression and autoimmunity in patients after clonal repopulation with antitumor lymphocytes. Science. 2002;298:850–854. doi: 10.1126/science.1076514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dudley M, et al. A phase I study of nonmyeloablative chemotherapy and adoptive transfer of autologous tumor antigen-specific T lymphocytes in patients with metastatic melanoma. J Immunother. 2002;25:243–251. doi: 10.1097/01.CJI.0000016820.36510.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu Z, et al. Homeostatic proliferation is a barrier to transplantation tolerance. Nat Med. 2004;10:87–92. doi: 10.1038/nm965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rocha B, von Boehmer H. Peripheral selection of the T cell repertoire. Science. 1991;251:1225–1228. doi: 10.1126/science.1900951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bell EB, et al. The stable and permanent expansion of functional T lymphocytes in athymic nude rats after a single injection of mature T cells. J Immunol. 1987;139:1379–1384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Murali-Krishna K, Ahmed R. Cutting edge: naïve T cells masquerading as memory cells. J Immunol. 2000;165:1733–1737. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.4.1733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oehen S, Brduscha-Riem K. Naïve cytotoxic T lymphocytes spontaneously acquire effector function in lymphocytopenic recipients: a pitfall for T cell memory studies? Eur J Immunol. 1999;29:608–614. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199902)29:02<608::AID-IMMU608>3.0.CO;2-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goldrath AW, et al. Naïve T cells transiently acquire a memory-like phenotype during homeostasis-driven proliferation. J Exp Med. 2000;192:557–564. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.4.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cho BK, et al. Homeostasis-stimulated proliferation drives naïve T cells to differentiate directly into memory T cells. J Exp Med. 2000;192:549–556. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.4.549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ernst B, et al. The peptide ligands mediating positive selection in the thymus control T cell survival and homeostatic proliferation in the periphery. Immunity. 1999;11:173–181. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80092-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.King C, et al. Homeostatic expansion of T cells during immune insufficiency generates autoimmunity. Cell. 2004;117:265–277. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00335-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dummer W, et al. T cell homeostatic proliferation elicits effective antitumor autoimmunity. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:185–192. doi: 10.1172/JCI15175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parmiani G, et al. Cancer immunotherapy with peptide-based vaccines: what have we achieved? Where are we going? J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94:805–818. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.11.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yu Z, Restifo NP. Cancer vaccines: progress reveals new complexities. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:289–294. doi: 10.1172/JCI16216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Palmer D, et al. Vaccine-stimulated, adoptively transferred CD8+ T cells traffic indiscriminately and ubiquitously while mediating specific tumor destruction. J Immunol. 2004;173:7209–7216. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.12.7209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dummer W, et al. Autologous regulation of naïve T cell homeostasis within the Tcell compartment. J Immunol. 2001;166:2460–2468. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.4.2460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goldrath AW, Bevan MJ. Selecting and maintaining a diverse T-cell repertoire. Nature. 1999;402:255–262. doi: 10.1038/46218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morrissey PJ, et al. Recombinant interleukin 7, pre-B cell growth factor, has costimulatory activity on purified mature T cells. J Exp Med. 1989;169:707–716. doi: 10.1084/jem.169.3.707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burton JD, et al. A lymphokine, provisionally designated interleukin T and produced by a human adult T-cell leukemia line, stimulates T-cell proliferation and the induction of lymphokine-activated killer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:4935–4939. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.11.4935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grabstein KH, et al. Cloning of a T cell growth factor that interacts with the β chain of the interleukin-2 receptor. Science. 1994;264:965–968. doi: 10.1126/science.8178155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kieper WC, et al. Overexpression of interleukin (IL)-7 leads to IL-15-independent generation of memory phenotype CD8+ T cells. J Exp Med. 2002;195:1533–1539. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marks-Konczalik J, et al. IL-2-induced activation-induced cell death is inhibited in IL-15 transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:11445–11450. doi: 10.1073/pnas.200363097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tough DF, et al. Induction of bystander T cell proliferation by viruses and type I interferon in vivo. Science. 1996;272:1947–1950. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5270.1947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang X, et al. Potent and selective stimulation of memory-phenotype CD8+ T cells in vivo by IL-15. Immunity. 1998;8:591–599. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80564-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tough DF, et al. T cell stimulation in vivo by lipopolysaccharide (LPS) J Exp Med. 1997;185:2089–2094. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.12.2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Geiselhart LA, et al. IL-7 administration alters the CD4:CD8 ratio, increases T cell numbers, and increases T cell function in the absence of activation. J Immunol. 2001;166:3019–3027. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.5.3019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Komschlies KL, et al. Administration of recombinant human IL-7 to mice alters the composition of B-lineage cells and Tcell subsets, enhances T cell function, and induces regression of established metastases. J Immunol. 1994;152:5776–5784. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fry TJ, et al. IL-7 therapy dramatically alters peripheral T-cell homeostasis in normal and SIV-infected non-human primates. Blood. 2003;101:2294–2299. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-07-2297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fry TJ, Mackall CL. Interleukin-7: master regulator of peripheral T-cell homeostasis? Trends Immunol. 2001;22:564–571. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(01)02028-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schluns KS, et al. Interleukin-7 mediates the homeostasis of naïve and memory CD8 T cells in vivo. Nat Immunol. 2000;1:426–432. doi: 10.1038/80868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Goldrath AW, et al. Cytokine requirements for acute and Basal homeostatic proliferation of naïve and memory CD8+ T cells. J Exp Med. 2002;195:1515–1522. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tan JT, et al. Interleukin (IL)-15 and IL-7 jointly regulate homeostatic proliferation of memory phenotype CD8+ cells but are not required for memory phenotype CD4+ cells. J Exp Med. 2002;195:1523–1532. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Judge AD, et al. Interleukin 15 controls both proliferation and survival of a subset of memory-phenotype CD8+ T cells. J Exp Med. 2002;196:935–946. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Becker TC, et al. Interleukin 15 is required for proliferative renewal of virus-specific memory CD8 T cells. J Exp Med. 2002;195:1541–1548. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tan JT, et al. IL-7 is critical for homeostatic proliferation and survival of naïve T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:8732–8737. doi: 10.1073/pnas.161126098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kaech SM, et al. Selective expression of the interleukin 7 receptor identifies effector CD8 T cells that give rise to long-lived memory cells. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:1191–1198. doi: 10.1038/ni1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Klebanoff CA, et al. IL-15 enhances the in vivo antitumor activity of tumor-reactive CD8+ T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:1969–1974. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307298101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang G, et al. In vivo antitumor activity of interleukin 21 mediated by natural killer cells. Cancer Res. 2003;63:9016–9022. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ozaki K, et al. A critical role for IL-21 in regulating immunoglobulin production. Science. 2002;298:1630–1634. doi: 10.1126/science.1077002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Moroz A, et al. IL-21 enhances and sustains CD8+ T cell responses to achieve durable tumor immunity: comparative evaluation of IL-2, IL-15, and IL-21. J Immunol. 2004;173:900–909. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.2.900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sakaguchi S. Naturally arising CD4+ regulatory T cells for immunologic self-tolerance and negative control of immune responses. Annu Rev Immunol. 2004;22:531–562. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Piccirillo CA, Shevach EM. Naturally-occurring CD4+CD25+ immunoregulatory T cells: central players in the arena of peripheral tolerance. Semin Immunol. 2004;16:81–88. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2003.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Malek TR, et al. CD4 regulatory T cells prevent lethal autoimmunity in IL-2Rβ-deficient mice. Implications for the non-redundant function of IL-2. Immunity. 2002;17:167–178. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00367-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fontenot JD, et al. Foxp3 programs the development and function of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:330–336. doi: 10.1038/ni904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Furtado GC, et al. Interleukin 2 signaling is required for CD4+ regulatory T cell function. J Exp Med. 2002;196:851–857. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Asano M, et al. Autoimmune disease as a consequence of developmental abnormality of a T cell subpopulation. J Exp Med. 1996;184:387–396. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.2.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.SuriPayer E, et al. CD4+CD25+ T cells inhibit both the induction and effector function of autoreactive T cells and represent a unique lineage of immunoregulatory cells. J Immunol. 1998;160:1212–1218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mottet C, et al. Cutting edge: cure of colitis by CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells. J Immunol. 2003;170:3939–3943. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.8.3939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Overwijk WW, et al. Vaccination with a recombinant vaccinia virus encoding a ‘self’ antigen induces autoimmune vitiligo and tumor cell destruction in mice: requirement for CD4+ T lymphocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:2982–2987. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.6.2982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Overwijk WW, Restifo NP. Autoimmunity and the immunotherapy of cancer: targeting the ‘self’ to destroy the ‘other’. Crit Rev Immunol. 2000;20:433–450. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bowne WB, et al. Coupling and uncoupling of tumor immunity and autoimmunity. J Exp Med. 1999;190:1717–1722. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.11.1717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Phan GQ, et al. Cancer regression and autoimmunity induced by cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 blockade in patients with metastatic melanoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:8372–8377. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1533209100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rosenberg SA, White DE. Vitiligo in patients with melanoma: normal tissue antigens can be targets for cancer immunotherapy. J Immunother Emphasis Tumor Immunol. 1996;19:81–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shimizu J, et al. Induction of tumor immunity by removing CD25+CD4+ T cells: a common basis between tumor immunity and autoimmunity. J Immunol. 1999;163:5211–5218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Liyanage UK, et al. Prevalence of regulatory T cells is increased in peripheral blood and tumor microenvironment of patients with pancreas or breast adenocarcinoma. J Immunol. 2002;169:2756–2761. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.5.2756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Casares N, et al. CD4+CD25+ regulatory cells inhibit activation of tumor-primed CD4+ T cells with IFN-γ-dependent antiangiogenic activity, as well as long-lasting tumor immunity elicited by peptide vaccination. J Immunol. 2003;171:5931–5939. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.11.5931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hori S, et al. Control of autoimmunity by naturally arising regulatory CD4+ T cells. Adv Immunol. 2003;81:331–371. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(03)81008-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Curiel TJ, et al. Specific recruitment of regulatory T cells in ovarian carcinoma fosters immune privilege and predicts reduced survival. Nat Med. 2004;10:942–949. doi: 10.1038/nm1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wang HY, et al. Tumor-specific human CD4+ regulatory T cells and their ligands: implications for immunotherapy. Immunity. 2004;20:107–118. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00359-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Javia LR, Rosenberg SA. CD4+CD25+ suppressor lymphocytes in the circulation of patients immunized against melanoma antigens. J Immunother. 2003;26:85–93. doi: 10.1097/00002371-200301000-00009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Woo EY, et al. Regulatory CD4+CD25+ T cells in tumors from patients with early-stage non-small cell lung cancer and late-stage ovarian cancer. Cancer Res. 2001;61:4766–4772. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Woo EY, et al. Cutting edge: Regulatory T cells from lung cancer patients directly inhibit autologous T cell proliferation. J Immunol. 2002;168:4272–4276. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.9.4272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Curiel TJ, et al. Specific recruitment of regulatory T cells in ovarian carcinoma fosters immune privilege and predicts reduced survival. Nat Med. 2004;10:942–949. doi: 10.1038/nm1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Chernysheva AD, et al. T cell proliferation induced by autologous non-T cells is a response to apoptotic cells processed by dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2002;169:1241–1250. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.3.1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Brown S, et al. Expression of TNF α by CD3+ and F4/80+ cells following irradiation preconditioning and allogeneic spleen cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2004;33:359–365. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1704362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sherman ML, et al. Regulation of tumor necrosis factor gene expression by ionizing radiation in human myeloid leukemia cells and peripheral blood monocytes. J Clin Invest. 1991;87:1794–1797. doi: 10.1172/JCI115199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Xun CQ, et al. Effect of total body irradiation, busulfan-cyclophosphamide, or cyclophosphamide conditioning on inflammatory cytokine release and development of acute and chronic graft-versus-host disease in H-2-incompatible transplanted SCID mice. Blood. 1994;83:2360–2367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rigby SM, et al. Total lymphoid irradiation nonmyeloablative preconditioning enriches for IL-4-producing CD4+-TNK cells and skews differentiation of immunocompetent donor CD4+ cells. Blood. 2003;101:2024–2032. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-05-1513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Torihata H, et al. Irradiation up-regulates CD80 expression through two different mechanisms in spleen B cells, B lymphoma cells, and dendritic cells. Immunology. 2004;112:219–227. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2004.01872.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zhang Y, et al. Preterminal host dendritic cells in irradiated mice prime CD8+ T cell-mediated acute graft-versus-host disease. J Clin Invest. 2002;109:1335–1344. doi: 10.1172/JCI14989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kedl RM, et al. T cells compete for access to antigen-bearing antigen-presenting cells. J Exp Med. 2000;192:1105–1113. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.8.1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Probst HC, et al. Cutting edge: competition for APC by CTLs of different specificities is not functionally important during induction of antiviral responses. J Immunol. 2002;168:5387–5391. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.11.5387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hill GR, et al. Total body irradiation and acute graft-versus-host disease: the role of gastrointestinal damage and inflammatory cytokines. Blood. 1997;90:3204–3213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kaech SM, Ahmed R. Memory CD8+ T cell differentiation: initial antigen encounter triggers a developmental program in naïve cells. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:415–422. doi: 10.1038/87720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.van Stipdon MJ, et al. Naïve CTLs require a single brief period of antigenic stimulation for clonal expansion and differentiation. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:423–429. doi: 10.1038/87730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Mattei F, et al. IL-15 is expressed by dendritic cells in response to type I IFN, double-stranded RNA, or lipopolysaccharide and promotes dendritic cell activation. J Immunol. 2001;167:1179–1187. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.3.1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Dudley ME, et al. Generation of tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte cultures for use in adoptive transfer therapy for melanoma patients. J Immunother. 2003;26:332–342. doi: 10.1097/00002371-200307000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Thornton AM, et al. Cutting edge: IL-2 is critically required for the in vitro activation of CD4+CD25+ T cell suppressor function. J Immunol. 2004;172:6519–6523. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.11.6519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Zheng L, et al. T cell growth cytokines cause the superinduction of molecules mediating antigen-induced T lymphocyte death. J Immunol. 1998;160:763–769. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]