Abstract

Lyme disease is caused by the spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi, which is transmitted through the bite of infected Ixodes ticks. Vaccination of mice with outer surface protein A (OspA) of B. burgdorferi has been shown to both protect mice against B. burgdorferi infection and reduce carriage of the organism in feeding ticks. Here we report the development of a murine-targeted OspA vaccine utilizing Vaccinia virus to interrupt transmission of disease in the reservoir hosts, thus reducing incidence of human disease. Oral vaccination of mice with a single dose of Vaccinia expressing OspA resulted in high antibody titers to OspA, 100% protection of vaccinated mice from infection with B. burgdorferi, and significant clearance of B. burgdorferi from infected ticks fed on vaccinated animals. The results indicate the vaccine is effective and may provide a manner to reduce incidence of Lyme disease.

Keywords: Lyme disease, Vaccinia virus, OspA

1. Introduction

Lyme disease is the most common vector borne disease in the United States. Transmission of Borrelia burgdorferi, the causative agent of Lyme disease, requires a complex interaction between the bacteria, its Ixodes tick vector and its mammalian reservoirs. Uninfected larval ticks acquire the bacteria during feeding on small rodents–primarily white-footed mice (Peromyscus leucopus). The spirochetes are transmitted to new hosts when the ticks feed as nymphs. Humans are incidental hosts and are most commonly infected by nymphal ticks, which feed during spring/summer months.

Despite increased awareness of Lyme disease and methods of avoidance, the incidence of human infections with B. burgdorferi has nearly doubled over the last decade [1]. A human vaccine (Lymerix, Glaxo SmithKline) was approved for Lyme disease and shown to be up to 87% protective [2]. The human vaccine consists of recombinant outer surface protein A (OspA). OspA is an outer surface protein of B. burgdorferi. OspA has been shown to be involved in the attachment of the spirochete to proteins in the tick midgut [3-5]. This protein is expressed while the bacteria is in its tick vector, but is down-regulated as the tick takes its blood meal and the bacteria migrate into the mammalian host [6-8]. Antibodies to OspA are taken up by the tick with its blood meal and kill the bacteria in the tick midgut, preventing transmission of the bacteria to the vaccinated host and eradicating the bacteria from the tick vector [9-15].

For multiple reasons including cost, need for frequent revaccinations, and a highly publicized, but theoretical risk of precipitating autoimmune arthritis in vaccinees with specific HLA haplotypes, sales of Lymerix declined rapidly after its initial introduction, and its manufacturer removed the vaccine from the market. As a result, there has been renewed interest in developing new strategies for the reduction of Lyme disease. Approaches to reduce tick numbers have included spraying of acaricides on vegetation, and direct application of acaricides to tick hosts using tubes filled with cotton impregnated with permethrin to target mice or a “four-poster” device which coats deer with an acaricide as they attempt to feed [16]. These have been shown to reduce tick numbers in limited areas, but have not successfully reduced the prevalence of Lyme-infected ticks over broad areas.

Vaccination of host animals is another strategy that may help decrease carriage of B. burgdorferi. During development for human use, the OspA vaccine was extensively tested in mice and was shown to protect mice from infection with B. burgdorferi and to clear the organism from Ixodes ticks feeding on vaccinated mice [9,10,15,17,18]. Recently, Tsao et al. have shown that subcutaneous vaccination of Peromyscus mice with OspA resulted in a reduction in the percent of ticks carrying B. burgdorferi compared with ticks recovered from an area where mice were give sham injections [19]. This provides evidence that a strategy for murine vaccination with OspA has the potential to reduce carriage of B. burgdorferi in its reservoir hosts and may be a complement to tick reduction methods. However, clearly, capture and subcutaneous vaccination of mice is not practicable on a large scale.

We are interested in developing an orally available delivery system for an OspA vaccine that would be suitable for field use in vaccinating mice. The ideal vector for delivery of a vaccine to wildlife should meet several important criteria: (1) it should be able to produce protection with a single dose, since uptake by the target animals is likely to be unpredictable; (2). it should be stable under a variety of environmental conditions; and (3). it should be non-toxic to both targeted and non-targeted wildlife species. Vaccinia virus (VV) meets all of these criteria for use as a vector in a murine-targeted vaccine, and has been extensively studied as a vaccine for smallpox, as a vector for vaccination against viral (HIV and rabies) [20,21] and parasitic diseases (malaria) [22]. To our knowledge, it has not yet been developed as a vector for vaccine against a bacterial disease.

The virus has numerous favorable characteristics as a vector including a wide host range, relatively high levels of protein synthesis, the ability to accept large fragments of foreign DNA without losing infectivity and relative stability under a variety of harsh environmental conditions. The ability of Vaccinia virus vaccines to result in high titer antibody responses is in part due to its ability to induce both humoral and cellular immune responses. It is particularly attractive as a vector for development of an oral vaccine for environmental release due to the large amount of safety and immunogenicity data generated as part of the development of the oral rabies (Raboral™) vaccine for the prevention of rabies in raccoons and foxes [23]. Vaccination programs of these types have led to reduction in incidence of rabies in animals by at least 80% throughout Europe and regions of the United States [23-27]. Vaccinia virus has been shown to have a very broad host range and is capable of infecting many different animals. However, studies have indicated that ingestion of Vaccinia virus is non-detrimental to indigenous wildlife including birds, small rodents, larger carnivores such as coyotes, raccoons, dogs, etc [23,28-31]. Additionally, human infections after accidental contact with the rabies vaccine have been rare [32,33]. Here we report on our studies using VV as a vector for the oral delivery of an OspA vaccine to reduce carriage of B. burgdorferi in its reservoir hosts.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Viral, bacterial and mouse strains

VV strain vRB12 [34], which is a vp37 deleted strain derived from the mouse adapted WR strain of VV, was the kind gift of Dr. Bernard Moss (National Institutes of Health). VV was grown and maintained in HeLa cells as described [35]. B. burgdorferi (strains N40 and B31) was cultivated in Barbour-Stoener-Kelly H (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO) at 37°C as we have previously described [36]. C3H mice were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Boston, MA). DBA mice were purchased from Taconic Laboratories (Germantown, NY). All mice were 4–10 weeks old when used.

2.2. Ticks

Ixodes dammini (also known as scapularis) ticks were obtained from a laboratory colony derived from an Ipswich, MA population that has been determined to be free of inherited spirochetal infection. To check for spirochetal infection in the colony, female ticks were fed on specific pathogen free rabbits (New Zealand White, Millbrook Laboratories, Amherst, MA) and allowed to oviposit. The resulting eggs were screened for evidence of Borrelia spp. infection by homogenizing 50 two-week-old eggs and examining an aliquot of the homogenate (dried on a slide and acetone fixed) by direct immunofluorescence. In addition, another aliquot of the homogenate was used to look for rickettsial infections by Castaneda staining of a dried smear followed by brightfield microscopy (×1000) [37].

To prepare infected ticks for use in our studies, larvae were allowed to feed to repletion 3 weeks after 4–7 B. burgdorferi (N40)-infected nymphs engorged upon specific pathogen free, DBA/2 mice [38]. Upon repletion, engorged larvae were collected, pooled in groups of 100–200 and permitted to molt to the nymphal stage at 21°C and 95% relative humidity. Prevalence of infection in each pool of ticks was determined 3 weeks after molting, by examining a sample of 10 ticks using an immunofluorescence procedure. Batches with greater than 50% infection were used for challenge studies.

2.3. Construction of VV-OspA

Several different recombinant OspA-VV constructs were created: (1) full-length OspA under the control of the VV early/late promoter; (2) full-length OspA under the control of its native 140 bp promoter; (3) a truncated OspA lacking the lipid attachment signal sequence; and (4) an additional truncated OspA whose native signal sequence was replaced with the murine tissue plasminogen activator (mt-PA) signal sequence as described [39]. The primers used are listed in Table 1. To construct the VV expressing OspA (VV-OspA), the ospA gene was amplified from DNA purified from B. burgdorferi (strain B31) by PCR. The PCR product was cloned into pCR2.1 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) as per the manufacturer's instructions. Clones containing the appropriate insert were selected and sequenced at the Tufts University Sequencing Facility. DNA from the selected clone was purified using QiaPrep Spin columns (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and restricted with NheI and NcoI. The restricted plasmid was gel purified using a Qiaquick column (Qiagen), and this DNA was ligated to an appropriately restricted viral vector, pRB21 (kind gift of Bernard Moss). pRB21 contains the VV early/late promoter as well as viral sequences flanking the vp37 in the viral genome for recombination with vRB12 to restore the function of the vp37 gene [40]. Ligation products were transformed into TOP10 electrocompetent cells and plated on LB agar plates containing kanamycin. Clones containing the correct insertion of the ospA gene were confirmed by restriction mapping, PCR, and gene sequencing using primers in the pRB21 flanking regions.

Table 1.

Primers used in the generation of VV-OspA constructs and detection of Borrelia

| Primer name | Sequence (5′–3′) | Function |

|---|---|---|

| 5'-Osp | gctagcatgaaaaaatatttattgggaataggtc | Full-length OspA construct |

| 140+Osp | gctagcagaaccaaacttaattaaaatcaaacttaattg | OspA plus native promoter construct |

| T-Osp | gctagcagccttaatagcatgtaagcaaaatg | Truncated OspA construct |

| mt-PA Osp | gctagcatgaagagagagctgctgtgtgtactgctgctttgtggactggctttcccattgcctgaccaggg | Tissue plasminogen signal sequence and OspA for mt-PA construct |

| OspA Rev | ccatggttattttaaagcgtttttaatttcatgaagtt | Reverse primer for all Osp constructs |

| flgB For | gccggctaatacccagcttcaag | Detection of Bb in tissue DNA |

| flgB Rev | atggaaacctccctcatttaaaattgc | Detection of Bb in tissue DNA |

| recA Sa | gtggatctattgtattagatgaggctctcg | Detection of Bb in tissue DNA |

| recA ASa | gccaaagttctgcaacattaacacctaaag | Detection of Bb in tissue DNA |

| VP37 5′ | gccatcgtcggtgtgttgtctaa | Primers outside of recombination site for detection of insert |

| VP37 3′ | agacataggaattggaggcgatgat |

Reference [36].

To generate recombinant Vaccinia, the pRB21/ospA construct was transformed into infected cells as described [35], with the exception that the lipid transfection reagent FuGENE 6 (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Indianapolis, IN) was used in place of CaCl2. Briefly, confluent CV-1 (American Tissue Culture Collection, Manassas, VA) were infected with VV-WR for 2 h at 37°C. Approximately 15 min before the end of the infection period, 6 μl of Fugene 6 reagent was added to 200 μl serum-free MEM. Two micrograms of pRB21/ospA purified DNA was added to the prediluted reagent at and the mixture was incubated at room temperature for 15 min. The inoculum was removed, and the DNA/lipid mixture was added drop-wise to the monolayer and incubated at room temperature for 30 min. Following the incubation, fresh MEM with 5% FBS was added and the cells were incubated at 37°C for 2 h. The media was then changed and the cells collected and prepared for plaque selection 2 days later. This procedure was repeated with pRB21 without insertion of ospA.

Plaques from recombinant virus were selected by plating on BS-C-1 cells (American Tissue Culture Collection) as described by Blasco and Moss [40]. Well-separated plaques were selected by pipeting agarose plugs from above the plaque while scraping the cells from the plaque. Plugs were transferred to fresh tubes containing MEM-2.5. The tubes were then subjected to 3 freeze/thaw cycles and trypsinization before use in infecting additional cells. A minimum of four rounds of plaque selection was performed to ensure pure recombinant virus was obtained.

Viral titering was performed in a manner similar to plaque selection except that following removal of the inoculum, fresh MEM-5 was added to each well. After 2 days, the media was removed and cells were stained using 0.1% crystal violet to facilitate counting.

2.4. Purification of recombinant virus for vaccination

Crude lysates were concentrated and purified using OptiPrep solution (60%, w/v, solution of iodixanol in water) (Axis-Shield, Oslo, Norway). Viral concentration was accomplished by centrifugation of virally infected cell lysates layered on a 50% (w/v) solution of OptiPrep reagent at 76,000 × g for 45 min. Concentrated virus was pooled for purification utilizing a self-generating gradient of 33% Optiprep solution overlaid with an equal volume of a 22% solution and allowed to equilibrate for 1 h. according to manufacturer's protocols. The purified band containing VV-OspA migrates to 1.12–1.15 g/ml. The purified virus was removed by pipetting, pooled, and titered before subsequent use.

2.5. Western blot

Whole cell extracts from HeLa cells infected with VV-OspA were analyzed for expression of OspA by Western blot. Briefly, equal number of cells were collected by centrifugation and resuspended in serum-free MEM. Infected cells were subjected to 3 freeze/thaw cycles with liquid nitrogen and vortexed extensively. To remove excess cell debris, the lysate was centrifuged at slow speed (300 × g) for 5 min and the supernatant collected. Samples from each lysate were added to lanes of a 10% acrylamide gel and separated by SDS-PAGE. Following separation, proteins were transferred to a polyvinyldifluoride membrane (Immobilon-P (Millipore, Bedford, MA)) using a semi-dry apparatus (Biorad). A replicate gel was run and stained with Coomassie blue to ensure equal loading of each sample. Western blots were performed as previously described [41] with the following modifications: (1) the primary antibody was a monoclonal anti-OspA antibody (Maine Biotechnology Services, Portland, ME) used at a 1:10,000 dilution; (2) the blots were developed using CDP-STAR (New England Biolabs) as per the manufacturer's instructions.

2.6. Mouse vaccination and challenge with B. burgdorferi

C3H/HeN mice were infected with VV-OspA or control VV-VP37 by gavage with 106, 107, 108, and 109 plaque-forming units (pfu) of virus, or sham vaccinated with an equal volume of culture media without virus. To examine Ab titer, mice were vaccinated with purified virus in groups of two, and the development of antibody titers to OspA was monitored by collection of small amounts of serum at weekly intervals by tail-vein bleeds. For studies of the effects of multiple vaccinations, subgroups of mice were given 108 pfu of vaccine 3 months after the initial vaccination and antibody titers again monitored. For comparison and use as a source of polyclonal Ab, control mice (4) were immunized with rOspA. The first vaccination was done with 5 μg of rOspA in a 1:1 (v/v) ratio of Freund's complete adjuvant and administered IM. Two subsequent boosts with Freund's incomplete adjuvant were delivered in the same manner at 1 and 3 weeks following the initial immunization.

To determine if VV-OspA was spread by horizontal transmission, an untreated animal was caged with 4 immunized littermates. Also, pairs of mice receiving 106 pfu were housed with a pair receiving 108 or 109 pfu of VV-OspA. Serum was taken from each mouse at biweekly intervals and examined for the presence of Vaccinia or OspA-specific Ab by ELISA and Western blot. To examine the potential of vertical transmission, breading pairs were immunized with 108 pfu of VV-OspA at 10–21 days of gestation. Pups were weaned at 21 days and removed from the parents to minimize the possibility of horizontal transfer. The pups were bled biweekly and analyzed for the presence of Ab as above.

Mice were challenged by allowing 6 B. burgdorferi (strain N40) infected Ixodes nymphs to feed to repletion. Mice were divided into 3 groups with 10 mice/group: VV-OspA-immunized, VV-VP37-immunized, and Sham vaccinated. Each mouse was anesthetized with Ketamine/Xylazine cocktail and 6 nymphal ticks were placed behind the ear of each mouse and allowed to attach. Cages were placed in water moats and the ticks were collected from the water moats after they had completed their feeding and detached from the animals.

The collected ticks were assayed for B. burgdorferi infection by both immunofluorescence and culture. Aliquots of tick homogenate were spotted on slides, dried, fixed in absolute acetone, and stored at –20c until analysis. Fluoresceinconjugated polyclonal rabbit anti B. burgdorferi sensu lato was used in a direct immunofluorescence procedure, as described [42]. To determine relative burdens of spirochetes within homogenates, slides were coded and blindly analyzed; burdens were qualitatively scored after examination at ×400. A separate aliquot of the tick midgut was placed into BSK-H media and incubated at 37°C. Cultures were monitored daily in a blinded manner for the presence of B. burgdorferi by darkfield microscopy.

Mice were assayed for infection with B. burgdorferi by culturing of an ear punch in BSK-H at 2, 3, and 4 weeks after tick challenge. At the time of sacrifice (5 weeks), skin, heart, spleen, and bladder tissue were placed into individual tubes of BSK-H and monitored for growth of B. burgdorferi by darkfield microscopy.

A portion of the heart tissue was also used to perform PCR for the presence of B. burgdorferi. DNA was isolated from the tissue using DNeasy (Qiagen) as per the manufacturer's instructions. PCR was used to detect B. burgdorferi in isolated tissues using primers specific for recA [43] and flgB as described in [44].

2.7. Detection of anti-OspA antibody by ELISA

Hi-bind 96 well plates (Costar, Corning, NY) were coated overnight at 4°C with lipidated rOspA diluted in PBS to 2.5 μg/ml. The rOspA was removed and the plates were blocked using PBS containing 1% BSA for 1 h at room temperature. Plates were then washed three times with PBS/0.1% Tween-20, and samples and standards were added to each well and incubated at room temperature for 1 h. Standards were prepared by generating serial dilutions of anti-OspA monoclonal antibody. Serum samples used in these assays were prepared using similar dilution factors used for standards to ensure that the measurements fell in the linear range of the assay. After 1 h, the plates were washed three times with PBS/0.1% TWEEN and incubated with anti-mouse AP-conjugated antibody (Promega, Madison, WI) diluted 1:10,000 in TBST at room temperature for 1 h. Plates were again washed as above, and incubated with alkaline phosphatase color substrate (Biorad) for 5–20 min. The reaction was terminated with 1.25 M H2SO4 (69.4 ml 36N H2SO4 and 930 ml H2O), and absorbance at 405 nm was measured. Antibody concentrations were determined based on the standard curve utilizing serial dilutions of the OspA antibody. Relative amounts of OspA antibody in serum was determined by subtracting background levels from blank wells, and determining fold increase in titer as compared to serum from VV-VP37-vaccinated animals to account for non-specific Ab production by the virus.

2.8. Statistics

The χ2-test was used to analyze efficacy of vaccination in cultures obtained from ticks following challenge experiments. Due to smaller sample sizes, the Fisher's exact test was used to determine if significant differences existed between mouse cultures and tick samples analyzed by DFA.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Construction of recombinant virus

vRB12 is a murine adapted VV strain that has a deletion in the vp37 gene that allows for simple plaque based selection when the gene of interest is recombined into vRB12 using a plasmid, which restores the vp37 gene function. We created 4 different variants of OspA inserted into VV. We inserted the full-length ospA under the control of its endogenous promoter because previous studies had suggested that expression of the ospA gene from a DNA vaccine was greater under the control of its own promoter than under a viral promoter [45]. The truncated OspA lacking the lipid attachment site was constructed because it was unclear to us whether the bacterial lipid attachment site would be recognized by eukaryotic host machinery and whether the retention of this site would be beneficial or harmful to the development of a protective antibody response. In experiments with recombinant OspA expressed from bacteria, truncation of the lipid attachment site has increased expression of the recombinant protein. However, in studies of humans and mice given recombinant OspA intramuscularly, lipidation was required for the generation of a protective antibody response [11,46]. The mt-PA signal sequence was added in an attempt to increase export of the protein and generate a higher antibody response. This strategy was previously used successfully by Gipson et al. [39]. Each of these genes was amplified from B. burgdorferi (B31) template DNA by PCR and cloned into the recombination plasmid pRB21 for co-transformation with vRB12 into CV-1 cells.

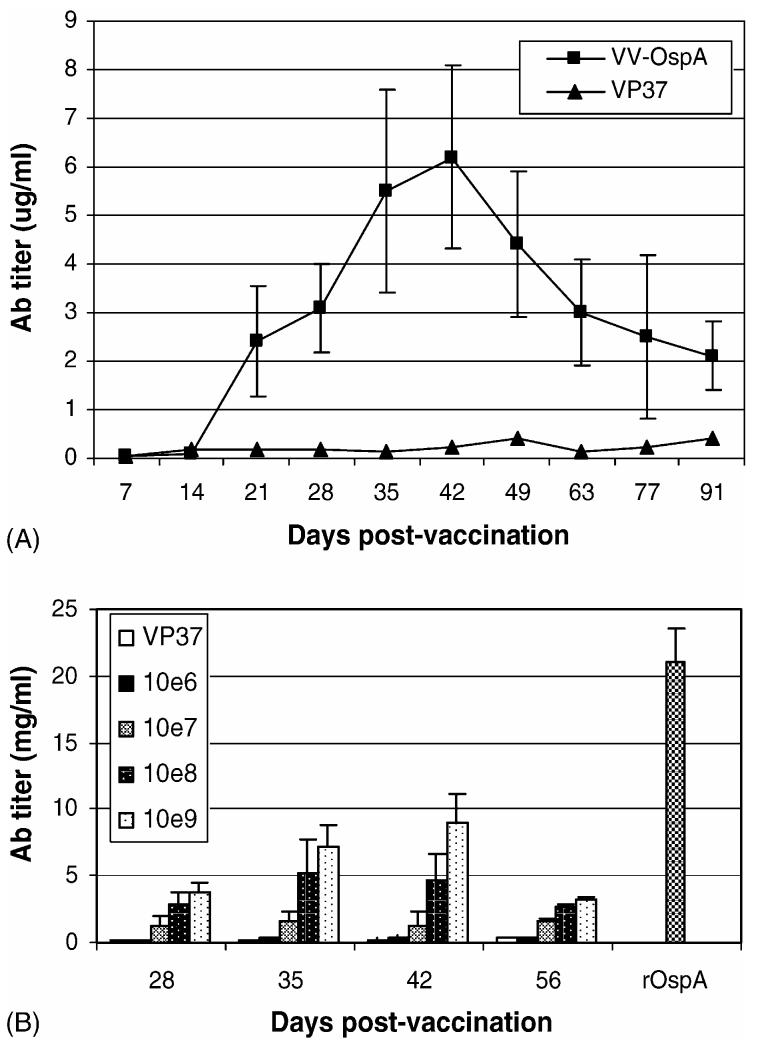

Recombinant virus was used to infect HeLa cells. Whole cell lysates of infected cells were subjected to Western blotting and examined for expression of OspA using a monoclonal anti-OspA antibody (Fig. 1). All of the constructs appeared to express OspA from HeLa cells, and there was no detectable increase in the amounts of OspA in supernatants regardless of construction. Truncated constructs demonstrated lower expression and have an altered molecular weight due to the truncation (Fig. 1, Lanes 2 and 4). The full-length OspA under the direct control of the VV early/late promoter had the highest levels of expression (lane 5). Supernatants from cultured viruses were also examined for the presence of OspA. Despite the addition of the mt-PA signal sequence, levels of OspA were similar in each of the constructs. As a result, all subsequent experiments were performed with the recombinant virus expressing the full-length OspA alone, now referred to as VV-OspA.

Fig. 1.

Expression of OspA by recombinant VV in vitro. Confluent Hela cells were infected with trypsinized virus for 3 days. Cells were collected and lysed by sonication. Whole cell lysates were examined for OspA expression by Western blot analysis using mAb to OspA. Lane 1: vector alone (VP37); Lane 2: truncated OspA; Lane 3: full-length OspA with 140 bp upstream promoter; Lane 4: truncated OspA with mt-PA signal sequence; Lane 5: full-length ospA gene (VV-OspA); Lane 6: positive control, purified Escherichia coli. recombinant OspA.

3.2. Antibody response to VV-OspA

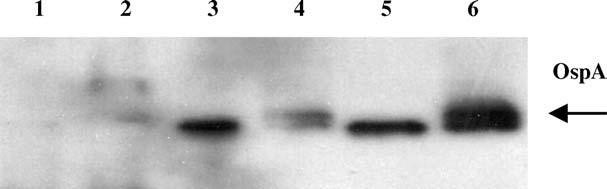

To determine whether mice infected with VV-OspA develop an antibody response to the recombinant OspA protein, mice were immunized by gavage with 108 pfu of VV-OspA or a control VV transformed with pRB21 without OspA (VP-37). The number of pfu was selected based on prior experience with vaccination of mice with VV rabies vaccine. Blood samples were taken at weekly intervals and examined for the presence OspA-specific IgG antibody by ELISA (Fig. 2A). Animals developed a detectable antibody response by day 21. The antibody titers continued to increase through day 42 peaking at titers reaching 30-fold higher than controls. Antibody titers began to fall gradually after day 42, but remained at approximately 5-fold above controls beyond day 90.

Fig. 2.

Generation of OspA-specific antibodies following immunization with VV-OspA. (A) Time course: mice (n = 4) were vaccinated with 108 pfu VV-OspA or VV-VP37 and serum samples were taken at weekly intervals to determine the time course of the immune response. (B) Dose-response: mice (4/group) were immunized with 106, 107, 108, or 109 pfu of VV-OspA or VV-VP37 and examined for OspA-specific antibodies weekly. Levels of OspA-specifc IgG were determined by ELISA. Data points include serum from a minimum of 4 separate mice, with each sample performed in duplicate; error bars indicate standard deviation.

We subsequently performed dose-response studies (Fig. 2B). Mice (n = 4/group) were vaccinated with 106, 107, 108 and 109 pfu of VV-OspA. Mice receiving 106 pfu demonstrated detectable titers at 35 and 42 days only. Peak titers were observed in animals receiving 109 pfu at 42 days. However, the difference between titers from mice receiving 108 and 109 pfu were not significantly different.

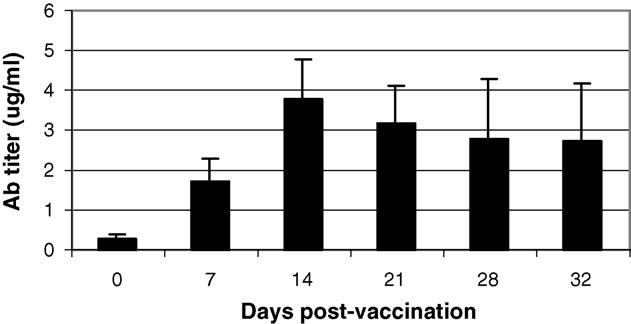

3.3. Effects of revaccination

In prior studies with OspA, as in our current study, antibody titers decrease with time, sometimes necessitating revaccination. A strategy for bait/vaccine placement could target peak feeding periods of the Ixodes ticks, specifically in spring (nymphs) and again in summer (larvae) to maintain peak titers during periods of tick activity. We sought to determine whether re-vaccination of mice would induce increased antibody titers to OspA or whether the initial vaccination would prevent re-infection with VV-OspA. To test this effect, mice that had been vaccinated with either VV-VP37 or low doses of VV-OspA 3 months previously were re-challenged with VV-OspA (108 pfu). Blood samples were again taken at weekly intervals and monitored for anti-OspA antibodies. Mice that had been immunized with low doses that had not generated antibody to OspA during the primary exposure demonstrated elevated titers of antibody within 14 days of the second vaccination (Fig. 3). Mice originally given 108 pfu of VV-VP37 also mounted an excellent antibody response to VV-OspA—equivalent to mice vaccinated for the first time. No detrimental affects of receiving 2 doses of the virus were noted in the mice. In mice originally vaccinated with VV-OspA who received a second dose of OspA, antibody titers quickly climbed and reached levels similar to those seen at the peak of the antibody response after the initial vaccination.

Fig. 3.

Effect of revaccination on antibody titers. Mice (n = 6) vaccinated with low doses of VV-OspA that did not develop a detectable OspA-Antibodies titer were revaccinated with 108 pfu of VV-OspA by gavage. Blood samples were taken weekly and OspA antibodies were measured by ELISA. Error bars indicate standard deviation.

These results suggest that there is reinfection of the mice with VV-OspA as OspA is only produced upon infection of a cell. To rule out the possibility that mice were responding to OspA protein in our VV preparations rather than to infection or reinfection with VV expressing OspA from infected cells, we tested our vaccine preparations for the presence of OspA by immunoblotting. The trypsinized VV purified by density centrifugation that was used to vaccinate mice had no detectable OspA protein in the preparations by immunoblotting (data not shown). Further, as seen in previous studies [47], mice gavaged with VV-OspA develop a strong antibody response to VV proteins showing that infection of cells occurs during uptake of the virus through the oral route.

Based on these results, we believe it will be possible to provide booster vaccines to the mice on a seasonal basis. In actual practice, revaccination may not occur, as the majority of Peromyscus mice in the wild do not survive more than 1 year [48]. However, for the minority of mice who would survive to receive a booster vaccination, mice in our study did show a response to revaccination with VV-OspA with the development of titers equivalent to those after the primary vaccination.

3.4. Horizontal and vertical transmission of VV

The ability to control the dissemination of a recombinant virus that is released into the environment is a significant concern. An advantage of the Vaccinia virus vector in other systems is that the virus does not appear to be transmitted horizontally from animal to animal [28,49]. While transmission of the vaccine from animal to animal would have the advantage of propagating herd immunity, it would also raise concerns about our ability to control the spread of the vaccine after release. Because the VV used in our vaccine is specifically mouse adapted and replication competent, we sought to determine if vaccinated animals could transmit the vaccine directly to other mice. Sentinel mice were placed in cages with mice vaccinated at 108 and 109 pfu rVV-OspA at the time of vaccination. Blood samples were taken at biweekly and examined for the presence of OspA antibodies. At no time were VV or OspA-specific antibodies detected in any of the mice. In addition, mice were sacrificed and DNA isolated in an attempt to detect OspA or Vaccinia-specific DNA by PCR. No evidence of VV-OspA infection was detected by PCR (data not shown). Pregnant mice were also infected with VV-OspA. None of the pups delivered from vaccinated mice showed evidence of OspA or Vaccinia-specific antibodies.

This data suggests that propagation of the recombinant VV-OspA will not occur in the wild and that spread can be controlled by termination of distribution of the vaccine.

3.5. Efficacy of anti-OspA antibodies generated by VV-OspA

Having established that mice vaccinated with VV-OspA develop significant antibody responses to OspA, we next sought to determine whether these antibodies were able to kill B. burgdorferi in the feeding tick and protect uninfected mice from infection with B. burgdorferi. Although there is extensive existing data on the protective efficacy of OspA antibody protection, because the rOspA was being expressed in a eukaryotic cell where processing and folding of the protein may be different from that of the native protein, the protective efficacy of antibodies to OspA generated by VV-OspA was tested directly. Ten mice were vaccinated with 108 pfu of VV-OspA, 108 pfu of VV-VP37 with an irrelevant insert, or sham by gavage. At 35 days, infected Ixodes nymphs were allowed to feed on mice. After repletion, the ticks were collected and examined for the presence of B. burgdorferi by DFA and by culture. Results are shown in Table 2. A total of 119 ticks were recovered. From vaccinated animals, 41 that fed on VV-OspA and 43 fed on VV-VP37 mice were recovered, while 35 ticks were obtained from the sham-vaccinated animals. Of the 35 ticks recovered from sham-vaccinated animals, 24 (69%) yielded positive cultures. Similarly, of the 43 ticks that had fed on VV-VP37-vaccinated animals, 29 (67%) were demonstrated to be positive for Bb by culture (p = 0.9). However, only 7 (17%) of 41 ticks recovered from VV-OspA vaccinated ticks were positive for B. burgdorferi by culture (p < 0.01). To confirm our culture results, a subset of the tick lysates were examined by DFA. DFA proved to be less sensitive than culture, but similar significant reductions in the number of midguts containing spirochetes was observed in VV-OspA immunized animals (0/22, 0%) as compared to sham (5/16, 31%) or VV-VP37 (5/22, 23%) animals (p < 0.01).

Table 2.

Efficacy of VV-OspA vaccination following feeding of infected ticks

| Treatment | No. of samples | Culture positive | Percentage | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ticks | Sham | 35 | 24 | 69 | |

| VV-VP37 | 43 | 29 | 67 | 0.9 | |

| VV-OspA | 41 | 7 | 17 | <0.01 | |

| Mice | Sham | 10 | 10 | 100 | |

| VV-VP37 | 10 | 10 | 100 | 1.00 | |

| VV-OspA | 10 | 0 | 0 | <0.01 |

The vaccinated mice fed on by B. burgdorferi infected ticks were monitored for the presence of B. burgdorferi by cultures of ear punch biopsies at 2, 3, and 4 weeks. Ear samples were cultured in BSK-H and examined daily by dark-field microscopy for the presence of spirochetes. At 5 weeks after tick feeding, the animals were sacrificed and samples of spleen, heart, bladder, and ear were cultured to determine if infection had occurred. Among control, unvaccinated animals, all mice were culture positive for B. burgdorferi. None of the cultures from mice vaccinated with VV-OspA were positive at any point in time (p < 0.01). C3H mice infected with B. burgdorferi developed grossly observable joint swelling of their tibio-tarsal joints. None of the mice vaccinated with VV-OspA developed joint swelling while all of the mice vaccinated with either VV-VP37 or sham developed gross ankle swelling.

Portions of the isolated tissues were also examined for the presence of spirochetes by PCR to confirm culture data. DNA was isolated from spleens and heart. PCR using two different primer sets from B. burgdorferi (recA and flgB) showed no evidence of spirochetal DNA in any of the vaccinated animals, while products were found in 80% of sham-vaccinated and control samples. Thus, the results of protection of mice and clearance of infection from ticks with a VV-OspA vaccine were similar to previous reports of OspA administered subcutaneously or intramuscularly.

In summary, we have developed an orally available, highly immunogenic and stable vaccine for use in a strategy of reducing the reservoir competence of mice and ticks for B. burgdorferi. The development of new strategies to control the growing epidemic of Lyme disease remains an important challenge. Field-testing will be required to establish the true efficacy of this vaccine, but the extensive prior testing of OspA vaccination in multiple other laboratories suggests that this vaccine has the potential to reduce human Lyme disease risk. Of note, our experiments tested laboratory strains of mice and not wild Peromyscus due to limited availability of Peromyscus mice. Previous studies of VV release with Raboral have shown that wild mice and other rodents are readily infected with VV and our own studies using limited numbers of Peromyscus have shown antibody responses similar to those seen with the laboratory strains of mice [30,31]. This may be important because Peromyscus are significantly different from inbred laboratory strains of mice. For example, although recombinant OspA protein fed to mice has resulted in antibody development and protection against infection in laboratory mice [18,50,51], development of a protective antibody response in Peromyscus fed recombinant OspA protein has not been reported, perhaps due to differences in the gastrointestinal tract of outbred mice.

The broad host range of VV may also have additional advantages. Tsao et al. demonstrated that a strategy of targeting Peromyscus mice with an OspA vaccine was effective in reducing the prevalence of B. burgdorferi in deer tick nymphs the following year [19]. However, they also found that in areas with lower mouse densities, small rodents other than Peromyscus were likely to be significant reservoirs of B. burgdorferi and important sources of larval and nymphal tick feeding. One of the advantages of the VV-OspA vaccine is that it does have a broad host range and can likely be used to target additional small rodent and even bird reservoirs simply by changing baiting strategies to target different animal species.

Clearly, many obstacles remain in the strategy of vaccinating wildlife reservoirs. Because of the behavioral patterns of mice differ substantially from that of raccoons and foxes targeted by the rabies vaccine, airdrops of baits as were used for successful deployment of the rabies vaccine may not be feasible. The time and costs of individual placements of bait boxes [52] is likely to be substantially more than that of airdrops, but would also decrease the chance of incidental human contact. The development of a suitable oral vaccine is the first step in testing a strategy for reduction of B. burgdorferi in wildlife reservoirs. The stability of the Vaccinia viral vectors in accepting large inserts of DNA also leaves open the possibility of developing vaccines that include multiple antigens of B. burgdorferi, antigens of other co-transmitted pathogens such as Babesia microti and Anaplasma phagocytophilum, or even tick antigens that may promote resistance to successful feeding of the tick on the vaccinated hosts.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Dr. Bernard Moss for his assistance with the design of the Vaccinia virus constructs and for providing the virus and vectors and Dr. Aruna Behera for her technical advice and for her help in reviewing the manuscript. This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health U01AI058266 (L.T.H.), R01AI44240 (L.T.H.), and R01 AI50043 (L.T.H.).

References

- 1.Steere AC, Coburn J, Glickstein L. The emergence of Lyme disease. J Clin Invest. 2004;113(8):1093–101. doi: 10.1172/JCI21681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sigal LH, Zahradnik JM, Lavin P, Patella SJ, Bryant G, Haselby R, et al. A vaccine consisting of recombinant Borrelia burgdorferi outer-surface protein A to prevent Lyme disease. Recombinant outer-surface protein A Lyme disease vaccine study consortium. N Engl J Med. 1998;339(4):216–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199807233390402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pal U, de Silva AM, Montgomery RR, Fish D, Anguita J, Anderson JF, et al. Attachment of Borrelia burgdorferi within Ixodes scapularis mediated by outer surface protein A. J Clin Invest. 2000;106(4):561–9. doi: 10.1172/JCI9427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pal U, Li X, Wang T, Montgomery RR, Ramamoorthi N, Desilva AM, et al. TROSPA, an Ixodes scapularis receptor for Borrelia burgdorferi. Cell. 2004;119(4):457–68. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang XF, Pal U, Alani SM, Fikrig E, Norgard MV. Essential role for OspA/B in the life cycle of the Lyme disease spirochete. J Exp Med. 2004;199(5):641–8. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hefty PS, Jolliff SE, Caimano MJ, Wikel SK, Akins DR. Changes in temporal and spatial patterns of outer surface lipoprotein expression generate population heterogeneity and antigenic diversity in the Lyme disease spirochete, Borrelia burgdorferi. Infect Immun. 2002;70(7):3468–78. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.7.3468-3478.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schwan TG, Piesman J. Temporal changes in outer surface proteins A and C of the lyme disease-associated spirochete, Borrelia burgdorferi, during the chain of infection in ticks and mice. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38(1):382–8. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.1.382-388.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang X, Goldberg MS, Popova TG, Schoeler GB, Wikel SK, Hagman KE, et al. Interdependence of environmental factors influencing reciprocal patterns of gene expression in virulent Borrelia burgdorferi. Mol Microbiol. 2000;37(6):1470–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.02104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Silva AM, Fish D, Burkot TR, Zhang Y, Fikrig E. OspA antibodies inhibit the acquisition of Borrelia burgdorferi by Ixodes ticks. Infect Immun. 1997;65(8):3146–50. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.8.3146-3150.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Silva AM, Telford SR, 3rd, Brunet LR, Barthold SW, FikrigF E. Borrelia burgdorferi OspA is an arthropod-specific transmission-blocking Lyme disease vaccine. J Exp Med. 1996;183(1):271–5. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.1.271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kramer MD, Wallich R, Simon MM. The outer surface protein A (OspA) of Borrelia burgdorferi: a vaccine candidate and bioactive mediator. Infection. 1996;24(2):190–4. doi: 10.1007/BF01713338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schaible UE, Wallich R, Kramer MD, Nerz G, Stehle T, Museteanu C, et al. Protection against Borrelia burgdorferi infection in SCID mice is conferred by presensitized spleen cells and partially by B but not T cells alone. Int Immunol. 1994;6(5):671–81. doi: 10.1093/intimm/6.5.671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Simon MM, Schaible UE, Kramer MD, Eckerskorn C, Museteanu C, Muller-Hermelink HK, et al. Recombinant outer surface protein a from Borrelia burgdorferi induces antibodies protective against spirochetal infection in mice. J Infect Dis. 1991;164(1):123–32. doi: 10.1093/infdis/164.1.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pal U, Montgomery RR, Lusitani D, Voet P, Weynants V, Malawista SE, et al. Inhibition of Borrelia burgdorferi-tick interactions in vivo by outer surface protein A antibody. J Immunol. 2001;166(12):7398–403. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.12.7398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Telford SR, Kantor FS, 3rd, Lobet Y, Barthold SW, Spielman A, Flavell RA, et al. Efficacy of human Lyme disease vaccine formulations in a mouse model. J Infect Dis. 1995;171(5):1368–70. doi: 10.1093/infdis/171.5.1368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pound JM, Miller JA, George JE, Lemeilleur CA. The ‘4-poster’ passive topical treatment device to apply acaricide for controlling ticks (Acari: Ixodidae) feeding on white-tailed deer. J Med Entomol. 2000;37(4):588–94. doi: 10.1603/0022-2585-37.4.588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wallich R, Kramer MD, Simon MM. The recombinant outer surface protein A (lipOspA) of Borrelia burgdorferi: a Lyme disease vaccine. Infection. 1996;24(5):396–7. doi: 10.1007/BF01716093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dunne M, al-Ramadi BK, Barthold SW, Flavell RA, Fikrig E. Oral vaccination with an attenuated Salmonella typhimurium strain expressing Borrelia burgdorferi OspA prevents murine Lyme borreliosis. Infect Immun. 1995;63(4):1611–4. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.4.1611-1614.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tsao JI, Wootton JT, Bunikis J, Luna MG, Fish D, Barbour AG. An ecological approach to preventing human infection: Vaccinating wild mouse reservoirs intervenes in the Lyme disease cycle. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101(52):18159–64. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405763102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Im EJ, Hanke T. MVA as a vector for vaccines against HIV-1. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2004;3(4 Suppl):S89–97. doi: 10.1586/14760584.3.4.s89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brochier B, Aubert MF, Pastoret PP, Masson E, Schon J, Lombard M, et al. Field use of a vaccinia-rabies recombinant vaccine for the control of sylvatic rabies in Europe and North America. Rev Sci Tech. 1996;15(3):947–70. doi: 10.20506/rst.15.3.965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prieur E, Gilbert SC, Schneider J, Moore AC, Sheu EG, Goonetilleke N, et al. A Plasmodium falciparum candidate vaccine based on a six-antigen polyprotein encoded by recombinant poxviruses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101(1):290–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307158101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pastoret PP, Boulanger D, Brochier B. Field trials of a recombinant rabies vaccine. Parasitology. 1995;110(Suppl):S37–42. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000001475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roscoe DE, Holste WC, Sorhage FE, Campbell C, Niezgoda M, Buchannan R, et al. Efficacy of an oral vaccinia-rabies glycoprotein recombinant vaccine in controlling epidemic raccoon rabies in New Jersey. J Wildl Dis. 1998;34(4):752–63. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-34.4.752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fearneyhough MG, Wilson PJ, Clark KA, Smith DR, Johnston DH, Hicks BN, et al. Results of an oral rabies vaccination program for coyotes. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1998;212(4):498–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cliquet F, Aubert M. Elimination of terrestrial rabies in Western European countries. Dev Biol (Basel) 2004:119185–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Masson E, Bruyere-Masson V, Vuillaume P, Lemoyne S, Aubert M. Rabies oral vaccination of foxes during the summer with the VRG vaccine bait. Vet Res. 1999;30(6):595–605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brochier B, Blancou J, Thomas I, Languet B, Artois M, Kieny MP, et al. Use of recombinant vaccinia-rabies glycoprotein virus for oral vaccination of wildlife against rabies: innocuity to several non-target bait consuming species. J Wildl Dis. 1989;25(4):540–7. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-25.4.540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hanlon CA, Niezgoda M, Hamir AN, Schumacher C, Koprowski H, Rupprecht CE. First North American field release of a vaccinia-rabies glycoprotein recombinant virus. J Wildl Dis. 1998;34(2):228–39. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-34.2.228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pastoret PP, Brochier B. The development and use of a vaccinia-rabies recombinant oral vaccine for the control of wildlife rabies; a link between Jenner and Pasteur. Epidemiol Infect. 1996;116(3):235–40. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800052535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pastoret PP, Brochier B, Boulanger D. Target and non-target effects of a recombinant vaccinia-rabies virus developed for fox vaccination against rabies. Dev Biol Stand. 1995:84183–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rupprecht CE, Blass L, Smith K, Orciari LA, Niezgoda M, Whit-field SG, et al. Human infection due to recombinant vaccinia-rabies glycoprotein virus. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(8):582–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa010560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McGuill MW, Kreindel SM, DeMaria A, Jr, Robbins AH, Rowell S, Hanlon CA, et al. Human contact with bait containing vaccine for control of rabies in wildlife. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1998;213(10):1413–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Blasco R, Moss B. Role of cell-associated enveloped vaccinia virus in cell-to-cell spread. J Virol. 1992;66(7):4170–9. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.7.4170-4179.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moss B. Expression of proteins in mammalian cells using vaccinia viral vectors. In: Fred RB, Ausubel M, Kingston RE, Moore DD, Seidman JG, Smith JA, Struhl K, editors. Current protocols in molecular biology. John Wiley & Sons Inc.; New York: 1991. pp. 16.15.1–7.16. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang XG, Lin B, Kidder JM, Telford S, Hu LT. Effects of environmental changes on expression of the oligopeptide permease (opp) genes of Borrelia burgdorferi. J Bacteriol. 2002;184(22):6198–206. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.22.6198-6206.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zdrodovskii PF, Golinevich HM. The Rickettsial Diseases. Pergamon Press; New York: 1960. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fikrig E, Telford SR, Barthold SW, Kantor FS, Flavell RA. Elimination of Borrelia burgdorferi from vector ticks feeding on OspA-immunized mice. PNAS. 1992;89(12):5418–21. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.12.5418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gipson CL, Davis NL, Johnston RE, de Silva AM. Evaluation of Venezuelan equine encephalitis (VEE) replicon-based outer surface protein A (OspA) vaccines in a tick challenge mouse model of Lyme disease. Vaccine. 2003;21(25–26):3875–84. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(03)00307-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Blasco R, Moss B. Selection of recombinant vaccinia viruses on the basis of plaque formation. Gene. 1995;158(2):157–62. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00149-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hu LT, Pratt SD, Perides G, Katz L, Rogers RA, Klempner MS. Isolation, cloning, and expression of a 70-kilodalton plasminogen binding protein of Borrelia burgdorferi. Infect Immun. 1997;65(12):4989–95. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.12.4989-4995.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Donahue JG, Piesman J, Spielman A. Reservoir competence of white-footed mice for Lyme disease spirochetes. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1987;36(1):92–6. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1987.36.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Morrison TB, Ma Y, Weis JH, Weis JJ. Rapid and sensitive quantification of Borrelia burgdorferi-infected mouse tissues by continuous fluorescent monitoring of PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37(4):987–92. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.4.987-992.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Barbour AG, Maupin GO, Teltow GJ, Carter CJ, Piesman J. Identification of an uncultivable Borrelia species in the hard tick Amblyomma americanum: possible agent of a Lyme disease-like illness. J Infect Dis. 1996;173(2):403–9. doi: 10.1093/infdis/173.2.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Simon MM, Gern L, Hauser P, Zhong W, Nielsen PJ, Kramer MD, et al. Protective immunization with plasmid DNA containing the outer surface lipoprotein A gene of Borrelia burgdorferi is independent of an eukaryotic promoter. Eur J Immunol. 1996;26(12):2831–40. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830261206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Van Hoecke C, Comberbach M, De Grave D, Desmons P, Fu D, Hauser P, et al. Evaluation of the safety, reactogenicity and immunogenicity of three recombinant outer surface protein (OspA) lyme vaccines in healthy adults. Vaccine. 1996;14(17–18):1620–6. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(96)00146-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Xu R, Johnson AJ, Liggitt D, Bevan MJ. Cellular and humoral immunity against vaccinia virus infection of mice. J Immunol. 2004;172(10):6265–71. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.10.6265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Terman C. Population dynamics. In: King J, editor. Biology of peromyscus (Rodentia) American Society of Mammologists Special Publications; 1968. p. 593. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brochier BM, Languet B, Blancou J, Kieny MP, Lecocq JP, Costy F, et al. Use of recombinant vaccinia-rabies virus for oral vaccination of fox cubs (Vulpes vulpes L.) against rabies. Vet Microbiol. 1988;18(2):103–8. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(88)90055-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gomes-Solecki MJ, Brisson DR, Dattwyler RJ. Oral vaccine that breaks the transmission cycle of the Lyme disease spirochete can be delivered via bait. Vaccine. 2005 doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.08.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Luke CJ, Huebner RC, Kasmiersky V, Barbour AG. Oral delivery of purified lipoprotein OspA protects mice from systemic infection with Borrelia burgdorferi. Vaccine. 1997;15(6–7):739–46. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(97)00219-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dolan MC, Maupin GO, Schneider BS, Denatale C, Hamon N, Cole C, et al. Control of immature Ixodes scapularis (Acari: Ixodidae) on rodent reservoirs of Borrelia burgdorferi in a residential community of southeastern Connecticut. J Med Entomol. 2004;41(6):1043–54. doi: 10.1603/0022-2585-41.6.1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]