Abstract

Cells and cell-free solutions of the culture filtrate of the bacterial symbiont, Xenorhabdus nematophila taken from the entomopathogenic nematode Steinernema carpocapsae in aqueous broth suspensions were lethal to larvae of the diamondback moth Plutella xylostella. Their application on leaves of Chinese cabbage indicated that the cells can penetrate into the insects in the absence of the nematode vector. Cell-free solutions containing metabolites were also proved as effective as bacterial cells suspension. The application of aqueous suspensions of cells of X. nematophila or solutions containing its toxic metabolites to the leaves represents a possible new strategy for controlling insect pests on foliage.

Keywords: Bacterial symbionts, Xenorhabdus nematophila, Entomopathogenic nematode, Steinernema carpocapsae, Diamondback moth, Plutella xylostella

INTRODUCTION

The diamondback moth Plutella xylostella L., (DBM) is an important and cosmopolitan pest of cruciferous crops (Harcourt, 1962). DBM has been controlled by various chemical pesticides but in recent years resistance to most of the conventional insecticides has developed (Sun et al., 1986). Bacillus thuringiensis is used also to control this pest but there are reports that DBM has developed resistance against the bacteria (Tabashink et al., 1990). The rapid development of resistance is probably associated with the very rapid reproduction of DBM i.e. more than 25 generations per year in the tropics (Keinmeesuke et al., 1985). The problems of insecticide resistance as well as the environmental and consumer health hazards associated with insecticide residues in plant material have focused attention on alternative methods for the control of DBM, hence the search for biocontrol agents for incorporation into IPM programmes against this insect is a dire need.

Entomopathogenic nematodes in the families Steinernematidae and Heterorhabditidae have been shown to be pathogenic to a wide range of agriculturally important pests and are useful alternatives to chemical insecticides for insect control (Kaya and Gaugler, 1993). The steinernematid, Steinernema carpocapsae has been shown to be effective against DBM (Morris, 1985; Ratnasinghe and Hague, 1997) but desiccation of the infective juveniles (IJs) on foliage reduces their effectiveness. Poinar and Thomas (1966) first reported that a single species of bacterium in the family Enterobacteriaceae was present in the anterior region of the IJ of S. carpocapsae. Since then investigators have shown that Steinernema species always carry bacteria of the genus Xenorhabdus (Akhurst and Boemare, 1990). The relationship between the nematode and the associated bacterium is mutualistic (Poinar, 1979) i.e. the association is essential for the survival of both the nematode and its symbiotic bacteria. Once an IJ has penetrated into the host haemocoele, the bacterial symbiont is released from the IJ gut, septicemia occurs and, within 48 h, insect death occurs. The bacteria reproduce rapidly and the IJs feed on bacteria and develop through 2–3 generations when new IJs are produced which leave the insect cadaver to search for new hosts.

Although IJs play an important role in the death of the insect host as the vector of the bacterial symbiont, the bacteria alone have been shown to cause insect death when injected into the haemocoele (Balcerzak, 1991; Gotz et al., 1981). The nematode, S. carpocapsae, carries a specific bacterium, Xenorhabdus nematophila. When the bacteria are reared in culture they have been shown to secrete a high-molecular weight protein into the growth medium which is lethal when injected into or fed to members of at least five insect genera (Ffrench-Constant and Bowen, 1999). Xenorhabdus nematophila is a gram negative aerobic bacterium with numerous petririchous flagella and has been shown to have swarming motility under moist conditions (Forst and Nealson, 1996; Givaudan et al., 1995). However, X. nematophila was not thought to have a free-living existence outside the nematode vector (IJ) or its predated host until the recent reports that the bacterium controlled the fire ant, Solenopsis invicta (Dudney, 1997) and the beet armyworm, Spodoptera exigua (Elawad et al., 1999). We describe here the effect of applying suspensions containing cells of the bacterial symbiont, X. nematophila, and its metabolites onto leaves of Chinese cabbage for the control of larvae of the diamondback moth, P. xylostella.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plants of Chinese cabbage cv. Wong Bok were obtained from the School of Plant Sciences, University of Reading, U.K. Plutella xylostella were reared on these plants in a growth room at 25 °C. Steinernema carpocapsae (All isolate), originally obtained from Biosys, U.S.A. was cultured in the greater wax moth, Galleria mellonella using the techniques described by Woodring and Kaya (1988).

Isolation of the bacterial symbiont

Galleria mellonella larvae after being infected with IJs of S. carpocapsae that had died 24–28 h were surface-sterilised in 70% alcohol for 10 min, flamed and allowed to dry in a laminar airflow cabinet for 2 min. Larvae were opened with sterile needles and scissors, care being taken not to damage the gut epithelium, and a drop of the oozing haemolymph was streaked with a needle onto nutrient agar [37 g nutrient agar (BDH); 25 mg bromothymol blue powder (Raymond); 4 ml of 1% 2, 3, 5 triphenyl-tetrerzolium chloride (BDH); 1000 ml distilled water] in Petri dishes which were sealed with Parafilm and incubated at 28 °C in the dark for 24 h. Single colonies of the bacterium X. nematophila were then selected and streaked onto new plates of nutrient agar, and sub-culturing continually until colonies of uniform size and morphology were obtained. The pathogenicity of isolates was confirmed by inoculating the bacteria into G. mellonella larvae and streaking the haemolymph of dead larvae onto nutrient agar. To produce large quantities of the bacterial symbiont, a single colony was selected and inoculated into a nutrient broth solution containing 15 g nutrient broth in 500 ml distilled water in a flask stoppered by sterile cotton wool. The flask was then placed in a shaking incubator at 150 rpm for 24 h at 28 °C. The concentration of bacterial cells in the broth suspension was determined by measuring the optical density in a spectrophotometer adjusted to 600 nm wavelength. For the experiments, the concentration of X. nematophila cells in the suspension was adjusted to 4×107 cells/ml, a dosage shown to be effective against larvae of S. exigua (Elawad et al., 1999). To obtain cell-free metabolites of the bacterial symbiont, the broth suspension of cells was filtered through a bacterial filter (pore size 0.2 μm). The efficiency of the filter was tested by streaking out small samples of the filtrate on NBTA agar.

Experiment 1: Application of cells and cells-free broth suspensions of X. nematophila against different DBM larval instars

One ml of a broth suspension containing cells of X. nematophila (4×107 cells/ml) and cell-free metabolites were sprayed onto both sides of detached leaves (7 cm×6 cm size) of Chinese cabbage with a small hand sprayer. 3% Tween-80 (Polyoxyethylene 20 sorbitan mono-oleate) was added as emulsifier in all experiments. Control was broth alone plus 3% Tween-80. Ten DBM larvae from each instar (2nd, 3rd and 4th) were placed on each leaf, which was dipped by its stalk into water in a small plastic container. Each leaf was placed in a larger plastic container (10 cm×6 cm×6 cm) to conserve moisture at 25 °C. Replication was 4-fold. Numbers of dead larval instars were counted after 48 h of application. All dead larval instars that had been treated with bacterial suspension were surface sterilized by immersion in 70% industrial methylated sprit (IMS) for 5 min. to kill the bacteria on the outside of the larvae. A small sample was taken from the haemolymph of dead larvae and streaked onto NBTA agar to determine whether cells of X. nematophila had penetrated into the larval haemocoele.

Experiment 2: Application of cells and cells-free broth suspensions of X. nematophila against DBM larvae at different temperatures

For this experiment three different temperatures were selected to determine the effect of temperature on the mortality of DBM larvae. Method of spraying of cells and cells-free broth suspensions on single detached Chinese cabbage leaves is already described in Experiment 1. Ten 3rd instar DBM larvae were placed on each leaf and incubated at 20, 25 and 30 °C. Replication was 4-fold. The number of dead larvae was determined after 2 days of application. Confirmation of dead larvae was done as described in Experiment 1.

Experiment 3: Application of cells and cells-free broth suspensions of X. nematophila against DBM larvae at different time intervals

Two ml of broth suspensions containing cells of X. nematophila and cell-free solution (containing 3% Tween-80) were sprayed onto both sides of detached leaves (7 cm×6 cm size) of Chinese cabbage (see Experiment 1 for detail). Control was broth alone plus 3% Tween-80. Ten 3rd instar DBM larvae were placed on each leaf and placed at 25 °C. Replication was 4-fold. The numbers of dead larvae were determined at 6, 12, 18, 24, 30, 36, 42 and 48 h after application. Confirmation of dead larvae was done as described in Experiment 1.

Experiment 4: Effect of different dose concentrations of X. nematophila on mortality of DBM larvae

A broth suspension containing 4×107 ml−1 of X. nematophila plus 3% Tween-80 was prepared as explained previously (Experiment 1) and diluted with broth solution to give suspensions containing the following dosage of cells: 4×102, 4×103, 4×104, 4×105, 4×106 and 4×107 cells/ml. Two ml of each suspension was sprayed onto the upper and lower sides of detached Chinese cabbage leaves (7 cm×6 cm size). Ten 3rd instar DBM larvae were placed on each leaf in a small container containing water which was then placed in a larger sealed container at 25 °C. Replication was 4-fold and mortality was determined after 2 days of application.

Experiment 5: Application of cells and cell-free broth suspensions of X. nematophila against DBM larvae using moist and dry Chinese cabbage leaves

The influence of moisture on the efficacy of cell suspensions and cell-free solutions of broth was investigated. Single detached leaves of Chinese cabbage (7 cm×6 cm) were sprayed on both sides with 2 ml of either a broth suspension containing 4×107 cells/ml or cell-free solution containing only metabolites, with 3% Tween-80 added as emulsifier. In first treatment (moist) the methodology was exactly the same as described above in the Experiment 1. In the second treatment (dry) the leaves treated with the cell suspensions and cell-free solutions of metabolites were dried in a laminar air-flow cabinet for 4 h before the DBM larvae were placed on the leaves which were then placed in a plastic container covered with muslin to maintain relatively dry atmosphere compared to the moist treatment. For both treatments ten 3rd instar DBM larvae were placed on each leaf and incubated at 25 °C. Mortality was determined after 2 days and replication was 4-fold.

Experiment 6: Effect of cells and cell-free suspensions of X. nematophila on DBM larvae using potted Chinese cabbage plants

In this experiment, one month old Chinese cabbage plants (10 leaves) growing in 9 cm pots (370 ml volume) were sprayed with 2 ml of either a broth suspension containing 4×107 cells/ml of X. nematophila or a cell-free solution of broth and metabolites. The control treatment was broth alone. Ten 3rd instar DBM larvae were placed on each plant, which was covered by a plastic cone to retain moisture. Plants were placed in a glasshouse at 25 °C. Insect mortality was determined after 2 days and replication was 4-fold.

Data taken from all experiments were transformed (arcsin transformation) prior to analyse statistically using regression technique of GENSTAT-5, Release 4.2 (Lawes Agricultural Trust, Rothamsted Experimental Station, UK). The same statistical package was used to determine any significant difference between means (t-test).

RESULTS

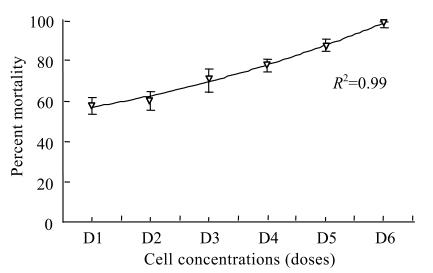

The cell and cell-free metabolites in broth treatments were significantly (P<0.05) effective as compared with broth alone against all DBM larval instars (Fig.1). Mortality was found to be 90% to 100% in all DBM larval instars when treated with either bacterial suspension or their metabolites solutions. Temperature showed a significant (P<0.05) effect on the mortality of DBM larvae (Fig.2). Application of either X. nematophila cell suspension or their toxic metabolites solution at 25 °C and 30 °C temperature resulted in higher mortality (92.5% to 100%) than 20 °C and caused only 65% mortality. However, no significant difference was found between X. nematophila cell suspension and their toxic metabolites solution. Insect mortality was increased as their exposure time to bacterial treatments increased (Fig.3). After 6 h, mortality was 7.5% and then significantly (P<0.05) increased to 65% and 77.5% when cells (R2=0.99) or cell-free solutions (R2=0.99) respectively were applied after 24 h. After 48 h post application insect mortality was observed to be 97.5% for both treatments, and there was no significant difference between the X. nematophila cell suspension and the cell-free broth metabolites solution. Broth alone had no significant effect on insect mortality (R2=0.96). A linear (R2=0.99) and significant (P<0.05) increase in mortality percentage of DBM larvae was observed with increasing in X. nematophila bacterial cell concentrations (Fig.4). Minimum dose of bacterial cells (4×102 ml−1) was less effective for controlling larvae (57.5%) than the high dose (4×107 ml−1) which resulted in 97.5% mortality. Both cell suspensions and cell-free broth-metabolites solution were significantly (P<0.05) most effective against DBM larvae when applied on moist leaves than was the broth control (Fig.5). Comparing both bacterial treatments (cells and cell-free broth-metabolites), cell-free broth-metabolites proved to be more effective (92.5% mortality) than the bacterial cells (62.5% mortality) when applied on moist leaves of Chinese cabbage than the respective treatments, 27.5% and 37.5%, on dry leaves. The application of X. nematophila cell suspensions and cell-free broth-metabolites solution against DBM larvae on whole Chinese cabbage plants were significantly (P<0.05) most effective than the broth control (Fig.6). However, there was no significant difference was observed between the bacterial cell suspensions and its cell-free broth-metabolites solution as a mortality of 95% and 97.5% respectively was attained in both treatments.

Fig. 1.

Effects of broth (△), cells suspension (▽) and cell-free metabolites (□) of X. nematophila on mortality percentage of different diamondback moth larvae instars. Vertical bars (where larger than the points) represent the standard error (s.e.) of variability at 5% level of probability

Fig. 2.

Mortality response of diamondback moth larvae to bacterial treatments, cells suspension (▽) and cell-free metabolites (□) of X. nematophila and broth (△) at 20, 25 and 30 °C temperature. Vertical bars (where larger than the points) represent the standard error (s.e.) of variability at 5% level of probability

Fig. 3.

Mortality response of diamondback moth larvae to cells suspension (▽) and cell-free metabolites (□) of Xenorhabdus nematophila and broth (△) after different time intervals. Vertical bars (where larger than the points) represent the standard error (s.e.) of variability at 5% level of probability

Fig. 4.

Effect of different bacterial cell concentrations (4×102, 4×103, 4×104, 4×105, 4×106 and 4×107 cells/ml) on mortality percentage of diamondback moth larvae. Vertical bars (where larger than the points) represent the standard error (s.e.) of variability at 5% level of probability

Fig. 5.

Effect of moist and dry condition of Chinese cabbage leaves on mortality of diamondback moth larvae treated with cells suspension (▽), cell-free solutions (□) of Xenorhabdus nematophila and broth control (△). Vertical bars (where larger than the points) represent the standard error (s.e.) of variability at 5% level of probability

Fig. 6.

Response of diamondback moth larvae to different bacterial treatments, cells suspension and cell-free metabolites and broth control when infected an intact Chinese cabbage plants. Vertical bars (where larger than the points) represent the standard error (s.e.) of variability at 5% level of probability

DISCUSSION

Cells of X. nematophila, normally found in the IJ of S. carpocapsae or in the cadavers of S. carpocapsae infected insect hosts, have been shown here to kill the larvae of P. xylostella when applied to foliar food of the larvae in the absence of nematode vector. Cell-free broth-metabolites solution from X. nematophila culture was more lethal to DBM larvae than the broth control, but bacterial cells of X. nematophila have numerous peritrichous flagella and exhibit swarming motility when grown under moist conditions on suitable solid media (Boemare et al., 1997; Elawad, 1998; Forst and Nealson, 1996). It is possible that cells can enter insects through the same natural openings that have been shown to be entry points for IJ of entomopathogenic nematodes i.e. mouth, anus and spiracles (Georgis and Hague, 1981; Mracek et al., 1988). The bacterial symbionts, X. nematophila and Photorhabdus luminescens, were unable to penetrate into the abdominal haemocoele when fed orally to the nymphs of the locust, Schistocerca gregaria (Mahar, 2003) but the IJs of S. feltiae and Heterorhabditis megidis were pathogenic to locusts when fed orally (Sambeek and Wiesner, 1999). Cells of X. nematophila were recovered from the pupae of the beet army worm S. exigua (Elawad et al., 1999) so it is possible that the spiracle, the only organ in pupae open to the external environment, is a possible point of entry for cells into the haemocoele. Further research is required to determine whether cells enter through the tracheal system and if they do, how they then penetrate in the haemocoele.

The results of the experiment on the effectiveness of different dosages of cells of X. nematophila indicate that relatively few cells of X. nematophila are lethal to DBM larvae. These figures for the number of cells of X. nematophila which cause 50% mortality of the targeted insect are much lower than the level of treatment proposed by Elawad et al.(1999) for S. exigua larvae. Though this may be explained by the general observations that Lepidoptera are more susceptible than Orthoptera to the entomopathogenic nematodes and their bacterial symbionts.

Broth suspensions containing cells of X. nematophila or solutions containing its cell-free metabolites are equally effective at controlling the DBM larvae though the broth control was not effective indicating that it is the bacterial metabolites which are probably responsible for the lethal effects observed because the metabolites are also present in cell suspensions. Our results are very similar to those in the reports by Ffrench-Constant and Bowen (1999) who showed that toxins from the X. nematophila were lethal to insects when fed in artificial diet.

Since the bacterial symbionts, cells and their metabolites from entomopathogenic nematodes are able to enter insects in the absence of the nematode vector there may be environmental concerns if large numbers of bacteria or their toxic metabolites were applied either to foliage or to the soil. The bacterial cells carried by the IJs of nematodes are released from insect cadavers to infect larvae and pupae in the soil, so their environmental impact needs to be investigated in detail, particularly if the treatments were applied in soil. S. carpocapsae which carries X. nematophila is currently exempt from pesticide regulations in Europe and the U.S.A., but efforts to use the bacterial symbionts themselves or their toxic metabolites may need to proceed cautiously because of the nature of the broad spectrum of the symbiont’s bioactivity (Webster et al., 2002), particularly in the rhizosphere.

The results presented here indicate that it is possible to apply either bacterial suspensions containing cells of X. nematophila or cell-free solutions containing its metabolites to control larvae of P. xylostella. The results with cell suspensions of X. nematophila support those in earlier reports by Elawad et al.(1999) on the control of larvae and pupae of S. exigua and by Dudney (1997) for the control of S. invicta. Since the application of cell suspensions may be environmentally undesirable it is probable that the application of toxic metabolites will be more commercially acceptable (Ensign et al., 2002). The effectiveness of both the cell suspensions and cell-free broth-metabolites was improved if the leaves remained moist during the application indicating that the activity of both the cells and their metabolites may be impaired if foliage became desiccated, a matter which needs more investigation. Further research is required also on the shelf-life of the toxic metabolites and on their persistence in soil if used against soil insects such as the black vine weevil, Otiorhynchus sulcatus. As indicated above, the nematode, S. carpocapsae which carries the bacterium, X. nematophila, is exempted from pesticide regulation. It seems likely that cell suspensions of the bacterium itself or solutions containing its toxic metabolites will have to be subjected to thorough testing and regulatory approval before they alone are used as a bio-pesticides.

References

- 1.Akhurst RJ, Boemare NE. Biology and Taxonomy of Xenorhabdus . In: Gaugler R, Kaya HK, editors. Entomopathogenic Nematodes in Biological Control. Boca Raton, Florida: C.R.C. Press; 1990. pp. 75–90. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Balcerzak M. Comparative studies on parasitism caused by entomogenous nematodes, Steinernema feltiae and Heterorhabditis bacteriophora. The roles of the nematode-bacterial complex, and of the associated bacteria alone, in pathogenesis. Acta Parasitologica Polonica. 1991;36:175–181. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boemare NE, Givaudan A, Brehelin M, Laumond C. Symbiosis and pathogencity of nematode bacterium complexes. Symbiosis. 1997;22:21–45. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dudney RA, inventor. Use of Xenorhabdus Nematophilus Im/l and 1906/1 for Fire Ant Control. 5,616,318. US Patent. 1997

- 5.Elawad SA. (Department of Agriculture, University of Reading, UK). 1998. Studies on the Taxonomy and Biology of A Newly Isolated Species of Steinernema (Steinernematidae: Nematoda) from the Tropics and Its Associated Bacteria. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elawad SA, Gowen SR, Hague NGM. Efficacy of bacterial symbionts from entomopathogenic nematodes against the beet army worm (Spodoptera exigua) Test of Agrochemicals and Cultivars No. 20, Annals of Applied Biology. 1999;134(Supplement):66–67. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ensign JC, Bowen DJ, Tenor JL, et al. Proteins from the Genus Xenorhabdus are Toxic to Insects on Oral Exposure. 0,147,148 A1. US patent. 2002

- 8.Ffrench-Constant R, Bowen D. Photorhabdus toxins: novel biological insecticides. Current Opinion in Microbiology. 1999;2:284–288. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(99)80049-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Forst S, Nealson K. Molecular biology of the symbiotic-pathogenic bacteria Xenorhabdus spp. and Photorhabdus spp. Microbiological Reviews. 1996;60:21–43. doi: 10.1128/mr.60.1.21-43.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Georgis R, Hague NGM. A neoplectanid nematode in the web-spinning larch sawfly Cephalcia lariciphila (Hymenoptera: Pamphiliidae) Annals of Applied Biology. 1981;99:171–177. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Givaudan AS, Baghdiguian S, Lanois A, Boemare N. Swarming and swimming changes concomitant with phase variation in Xenorhabdus nematophilus . Applied Environmental Microbiology. 1995;61:1408–1413. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.4.1408-1413.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gotz P, Boman A, Boman HG, editors. Interactions between insect immunity and an insect-pathogenic nematode with symbiotic bacteria; Proceedings of Royal Society London; 1981. pp. 333–350. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harcourt DG, editor. Biology of cabbage caterpillars in eastern Ontario; Proceedings of the Entomological Society Ontario; 1962. pp. 61–75. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaya HK, Gaugler R. Entomopathogenic nematodes. Annual Review of Entomology. 1993;38:181–206. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Keinmeesuke P, Vattanatangum P, Sarnthoy O, et al. Life Table of Diamondback Moth and Its Egg Parasite Trichogrammatoidea bactrae in Thailand. In: Talekar NS, editor. Diamondback Moth and Other Crucifer Pests: Proceedings of the Second International Workshop, Asian Vegetable Research and Development Center; AVRDC; Tainan, Taiwan. 1985. pp. 309–315. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mahar AN. (Department of Agriculture, University of Reading, UK). 2003. The Efficacy of Bacteria Isolated from Entomopathogenic Nematodes Against the Diamondback Moth Plutella Xylostella L. (Lepidoptera: Yponomeutidae) [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morris ON. Susceptibility of 31 species of agricultural insect pests to entomopathogenic nematodes Steinernema feltiae and Heterorhabditis bacteriophora . Canadian Entomologist. 1985;117:401–407. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mracek Z, Hanzal R, Kodrik D. Sites of penetrations of juveniles Steinernematids and Heterorhabditis (Nematoda) in the larvae of G. mellonella (Lepidoptera) Journal of Invertebrate Pathology. 1988;52:477–482. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Poinar JrGO. Nematodes for Biological Control of Insects. Boca Raton, Florida: C.R.C. Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Poinar JrGO, Thomas GM. Significance of Achromobacter nematophilus Poinar and Thomas (Achromobacteriaceae: Eubacteriales) in the development of the nematode DD-136 (Neoaplectanta sp. Steinernematidae) Parasitology. 1966;56:385–390. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000070980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ratnasinghe G, Hague NGM. Efficacy of Entomopathogenic nematodes against the diamondback moth, Plutella xylostella (Lepidoptera: Yponomeutidae) Pakistan Journal of Nematology. 1997;15:45–53. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sambeek J, Wiesner A. Successful parasitation of locusts by entomopathogenic nematodes is correlated with inhibition of insect phagocytes. Journal of Invertebrate Pathology. 1999;73:154–161. doi: 10.1006/jipa.1998.4823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sun CN, Wu TK, Chen JS, et al. Insecticide Resistance in Diamondback Moth. In: Talekar NS, Griggs TD, editors. Diamondback Moth Management: Proceedings of the First International Workshop, Asian Vegetable Research and Development Center; AVRDC; Shanhua, Taiwan. 1986. pp. 359–371. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tabashink BE, Cushing NL, Finson N, Johnson MW. Field development of resistance to Bacillus thuringiensis in Diamondback moth (Lepidoptera: Plutellidea) Journal of Economic Entomology. 1990;83:1671–1676. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Webster JM, Chen G, Hu K, et al. Bacterial Metabolites. In: Gaugler R, editor. Entomopathogenic Nematology. Wallingford, UK: CAB International; 2002. pp. 99–114. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Woodring JL, Kaya HK Arkansas Experiment Station, Fayetteville, AR, USA. Steinernematid and Heterorhabditid Nematodes: A Handbook of Biology and Techniques. 1988. p. 28. (Southern Cooperatives Series Bulletin 331). [Google Scholar]