Abstract

Objective: To explore the effects of transforming growth factor β1 (TGF-β1) on dendritic cells (DC). Methods: Murine bone marrow cells were cultured with GM-CSF and TGF-β1 to develop TGF-β1-treated DC (TGFβ-DC). Then they were stimulated by lipopolysaccharide (LPS). Their phenotypes were assessed by flow cytometry (FCM). The allogeneic stimulating capacity of DC was measured by mixed lymphocyte reaction (MLR) using BrdU ELISA method and IL-12p70 protein was detected by ELISA. The expression of Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) was analyzed by semi quantitative reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) and FCM. Results: Compared to immature DC (imDC) cultured by GM-CSF alone, the TGFβ-DC express lower CD80, CD86, I-Ab and CD40. The TGFβ-DC were resistant to maturation with LPS. Maturation resistance was evident from a failure to up-regulate co-stimulatory molecules (CMs), to stimulate larger T cells proliferation and to enhance secretion of IL-12p70. We also found that TGF-β1 could down-regulate TLR4 expression on TGFβ-DC. Conclusion: TGFβ-DC are resistant to maturation stimulus (LPS) and might have some correlation with the down-modulation of TLR4 expression.

Keywords: Dendritic cells, Transforming growth factor β1, Toll-like receptor 4

INTRODUCTION

Dendritic cells (DC) are the most potent antigen-presenting cells (APCs) and are the only cell type that can activate naive T cells (Banchereau and Steinman, 1998). Former intense investigations of DC were focused on utilizing their immunostimulatory properties for vaccination purposes either for pathogens or for cancers. However, it had recently become evident that DC can be used for immune regulation; either for treatment of autoimmunity or for transplant rejection (Steinman et al., 2003). The functional activities of DC are mainly dependent on their maturational stage. In contrast to the fact that mature DC (mDC) could stimulate T cells through high expression of MHC II and co-stimulatory molecules (CMs), immature DC (imDC) inhibit T cell responses. The immune regulatory aspects of imDC include the direct killing of T cells, induction of T cell anergy or stimulation of T regulatory cell (Treg) generation (Jonuleit et al., 2001).

DC express a wide array of Toll-like receptors (TLRs), such as TLR1, TLR2, TLR3, TLR4, TLR5, TLR6 and TLR8 that might receive various microbial signals and initiate specific acquired/adaptive immune responses as professional APCs (Kadowaki et al., 2001). Among them, TLR4 has been reported to act as a receptor for lipopolysaccharide (LPS), an integral component of the outer membranes of gram-negative bacteria. LPS can stimulate imDC to mDC via TLR4 signal transduction pathway.

Transforming growth factor β1 (TGF-β1) is a secreted protein that regulates proliferation, differentiation and death of various cell types (Moustakas et al., 2002). Previous report showed that TGF-β1 could inhibit DC maturation; and that TGF-β1-treated DC (TGFβ-DC) induced allogeneic specific immune tolerance (Hirano et al., 2000). In this study, we further evaluated the effects of TGF-β1 on murine bone marrow (BM)-derived DC maturation and function, including effects on morphology; expression of MHC II and CMs; response to LPS; IL-12p70 production; stimulatory capacity for T cell proliferation and expression of TLR4.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Male 8- to 12-wk-old C57BL/6J (B6, H2Kb, IAb) and BALB/c (H2Kd, IAd) mice purchased from Shanghai Laboratory Animal Center, Chinese Academy of Sciences were housed in a special pathogen-free environment at Zhejiang University.

Reagents

The culture medium was RMPI 1640 (GIBCO) supplemented with 10% v/v fetal calf serum (FCS), 2 mmol/L L-glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (referred to subsequently as complete medium). Recombinant mouse (rm) GM-CSF, rmIL-4 and recombinant human (rh) TGF-β1 were purchased from R&D System (Minneapolis, MN), LPS (Escherichia coli serotype 026:B6) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis. MO).

Generation of BM-derived DC

Different populations of DC were generated from bone marrow progenitor cells as described in (Min et al., 2000; Hirano et al., 2000). Briefly, B6 murine bone marrow cells were flushed from femurs and tibias, filtered through nylon mesh, and red cells were lysed with ammonium chloride; then cultured in 6-well tissue culture plates (Costar) at an initial density of 2×106 ml−1 in 3 ml/well complete medium containing different cytokines cocktail. The BM cells were incubated at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2. The culture medium was changed every two days by gently swirling the plates, aspirating half of the medium, and afterwards replaced with the same volume of fresh medium containing the initial concentration of cytokine(s). Many of the growing granulocytes were removed during these washes. On day 7, the suspending cells were collected. Three cell populations of predominantly imDC (4 ng/ml rmGM-CSF-stimulated), TGF-β1-treated DC (TGFβ-DC, 4 ng/ml rmGM-CSF+0.2 ng/ml rhTGF-β1-stimulated) and mDC (4 ng/ml rmGM-CSF+1000 U/ml rmIL-4-stimulated) were obtained respectively. In certain experiments, the cells were transferred to other plates and cultured with 1 μg/ml LPS for 2 days.

Flow Cytometry (FCM)

DC phenotypes were analyzed by FCM, using an EPICS XL-MCL Cell Analysis System (Coulter, Miami, FL). The following mAbs were purchased from Caltag (Burlingame, CA): FITC-conjugated anti-mouse I-Ab (25-5-16s), anti-mouse CD86 (RMMP-2), and PE-conjugated anti-mouse CD80 (RMMP-1), anti-mouse CD40 (3/23). FITC-conjugated anti-CD11c (HL-3) was purchased from PharMingen (San Diego, CA) and PE-conjugated anti-TLR4/MD2 (MTS510) was from eBioscience (San Diego, CA). The isotype matched control mAbs were purchased from the corresponding manufacturers.

Mixed leukocyte reaction (MLR) and 5-bromo-2-deoxyuridine (BrdU) ELISA

To determine the Ag-presenting capacity of DC in vitro, one-way MLR was performed with mitomycin C-treated (50 μg/ml, 30 min) DC as stimulators and nylon wool-purified BALB/c splenic T cells (2×105) as responders. Cultures were established in triplicate in 96-well, round-bottom microculture plates (Nunclon, 200 μl/well) and maintained in complete medium for 96 hours. The proliferation of T cells was determined using colorimetric immunoassay for the quantification of cell proliferation, based on the measurement of BrdU incorporation during DNA synthesis. The BrdU ELISA method was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis). Briefly, 20 μl/well BrdU of 200 μmol/L BrdU labeling solution was added for the final 20 h of culture. After 96 h stimulation, plates were centrifuged and denatured with FixDenat solution, then incubated for 90 min with 1:100 diluted mouse anti-BrdU mAbs conjugated to peroxidase (100 μl/well). After removing the antibody conjugate, 100 μl TMB substrate solutions were added for 20 min and the reaction stopped by adding 1 mol/L H2SO4 solution. The absorbance was measured at 450 nm with a reference wavelength at 690 nm using an ELISA plate reader (Bio-Rad).

ELISA

Murine IL-12p70 was measured in culture supernatants using commercially available kit (Lifekey, Monmouth, NJ).

RNA extraction and reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) of TLR4

Total cellular RNA was extracted using the Trizol RNA extraction kit (GIBCO BRL) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA yield and purity were determined spectrophotometrically at 260/280 nm. cDNA synthesis was performed using MMLV reverse transcriptase and oligo (dT15). For PCR reactions, primer sequences were as follows: β-actin (sense: 5′-GAT GAC GAT ATC GCT GCG CTG-3′; antisense: 5′-GTA CGA CCA GAG GCA TAC AGG-3′) and TLR4 (Liu et al., 2002) (sense: 5′-AGT GGG TCA AGG AAC AGA AGC A-3′; antisense: 5′-CTT TAC CAG CTC ATT TCT CAC C-3′), respectively. The primers were synthesized by Shanghai Shenggong Biological Engineering Company. The expected sizes of the PCR products were 440 bp for β-actin and 311 bp for TLR4. The PCR for TLR4 was performed by 30 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 30 s, annealing at 55 °C for 45 s and extension at 72 °C for 45 s in a final volume of 25 μl. The products were separated by electrophoresis on 1.5% agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide, and photographed with gel automatic photography. A gel thin-layer scan for semiquantitive assay was performed. The relative levels of TLR4 mRNA expression were obtained from their individual signal density to β-actin ratio.

Statistical analysis

Comparison of means was performed by two-tailed student t test. P<0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. All calculations were performed on an SPSS for Windows, version 10.0.

RESULTS

TGF-β1 inhibits the maturation of murine BM-derived DC

To investigate the effect of TGF-β1 on the phenotype and maturation of DC, BM cells were cultured in the presence of TGF-β1 from the beginning of the culture. The expressions of I-Ab (MHC-II) and CMs were analyzed by FCM. As shown in Table 1, both TGFβ-DC and imDC expressed mouse BM-derived DC specific marker CD11c (P>0.05). Surface expression of CD80, CD86, CD40, I-Ab were inhibited by addition of TGF-β1, especially in CD80, CD86 (P<0.05), whereas mDC expressed high levels of surface CMs. Furthermore, the imDC were sensitive to further maturation in response to LPS by showing increased levels of MHC class II, CD80, CD86 and CD40. In marked contrast, TGF-β1 prevented this LPS-mediated maturation and maintained the cells in the immature state, with low levels of surface CMs expression.

Table 1.

TGF-β1 inhibits the expression of surface molecules on DC (χ̄±s, n=3)

| Surface Ag | Positive cells (%) |

||||

| imDC | TGFβ-DC | imDC+LPS | TGFβ-DC+LPS | mDC | |

| CD11c | 50.67±5.63 | 41.73±4.0 | 66.43±5.28 | 45.30±5.30 | 79.53±10.18 |

| I-Ab | 16.50±6.29 | 7.88±0.90 | 41.33±4.67 | 12.17±1.64## | 86.17±3.55 |

| CD80 | 13.90±7.22 | 4.14±0.95* | 33.47±6.77 | 6.53±5.43# | 61.63±19.58 |

| CD86 | 20.63±5.03 | 8.60±0.75* | 37.70±8.07 | 12.83±3.52 | 77.23±10.51 |

| CD40 | 6.32±4.71 | 1.42±1.32 | 8.04±6.90 | 2.90±1.45 | 29.27±13.79 |

Compared with imDC, P<0.05

Compared with imDC+LPS, P<0.05

Compared with imDC+LPS, P<0.01

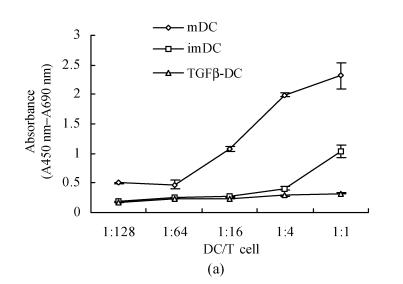

TGF-β1 inhibits allostimulatory activity of DC

After 96 h MLR, TGFβ-DC had weaker stimulating capacity than imDC, especially when the ratio of DC and T cells were 1:4 and 1:1 (P<0.05). On the contrary, significantly allostimulatory activity was seen in mDC (Fig.1a). Importantly, maturation induced by LPS stimulation strongly promoted the allostimulatory capacity of imDC, whereas exposure to LPS only slightly affected the allostimulatory capacity of TGFβ-DC (Fig.1b). This observation indicated that TGF-β1-treated DC were partially maturation resistant.

Fig. 1.

TGFβ-DC had weaker stimulating capacity than imDC (a) and exposure to LPS only slightly affected the allostimulatory capacity of TGFβ-DC (b) (χ̄±s, n=3)

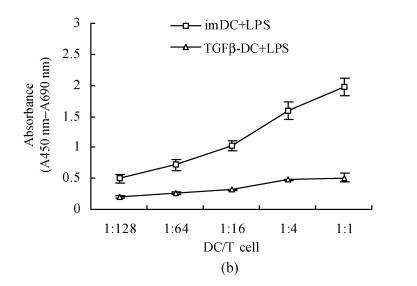

TGFβ-DC show impaired IL-12p70 production

After stimulation of imDC and TGFβ-DC with LPS, production of IL-12p70 in the culture supernatant was detected at different time points. The release of IL-12p70 of TGFβ-DC was significantly less than that of imDC (Fig.2), indicating that exposure to TGF-β1 impaired the capability of DC to produce high amounts of bioactive IL-12p70.

Fig. 2.

Impaired IL-12 production by TGFβ-DC (χ̄±s, n=6)

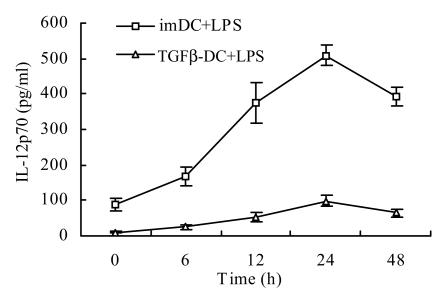

Estimation of the expression of TLR4 on DC

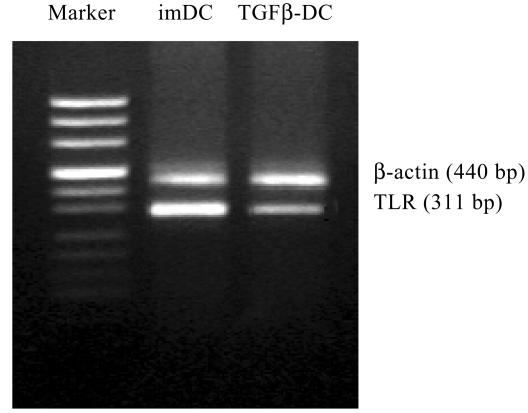

It had been previously demonstrated that LPS is recognized by TLR4. Therefore, we analyzed the expression of TLR4 mRNA on imDC and TGFβ-DC by RT-PCR. To our surprise, although DC clearly expressed TLR4, TGFβ-DC expressed more weakly than imDC (Fig.3).

Fig. 3.

TLR4 mRNA expression in TGFβ-DC was weaker than that in imDC

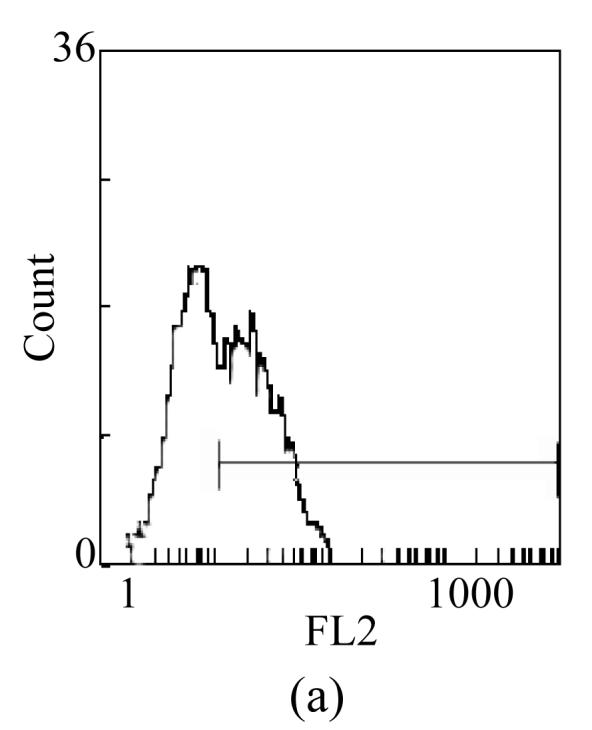

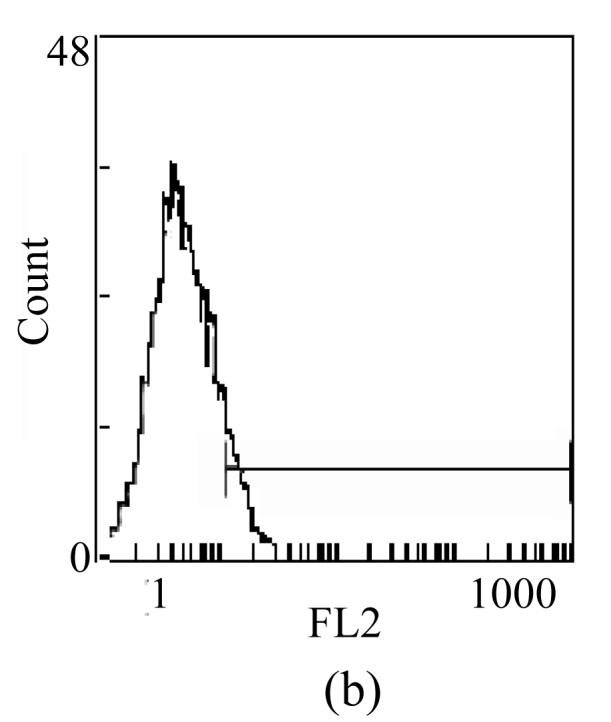

The expressions of TLR4 on DC were also estimated by FCM. Consistent with the result of RT-PCR, the positive expression percentages of TLR4 on imDC and TGFβ-DC were ((51.8±3.89)% vs (15.7±4.13)%, P<0.01). Moreover, the mean fluorescence intensities (MFIs) of TLR4 on imDC and TGFβ-DC were (2.37±0.26 vs 1.36±0.17, P<0.05) (Fig.4). The results agreed with previous find ings that TGFβ-DC responded weakly to LPS.

Fig. 4.

Surface expression of TLR4 on TGFβ-DC (b) was lower than that on imDC (a)

DISCUSSION

Evidences accumulated that immature donor DC deficient in surface CMs could inhibit alloantigen-specific T cell responses and prolong the survival of heart, kidney or pancreatic-islet allografts (Hackstein et al., 2001). However, the tolerogenic properties of these imDC were often unstable or inconsistent, with most study efforts achieving only modest improvement in graft outcome. Failure to consistently induce long-term graft acceptance in nonimmunosuppressed recipients appears to reflect the eventual in vivo maturation of the donor-derived DC following their in vivo administration.

It is generally accepted that DC mature when they are cultured in LPS, TNF-α or with anti-CD40 antibodies in vitro. Maturation resistance has been reported for DC cultured in IL-10 (Steinbrink et al., 1997), 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (Berer et al., 2000). Here, the TGFβ-DC were resistant to maturation by LPS, as the expression of CMs was slightly increased. After 96 h MLR, LPS stimulating TGFβ-DC had weaker allogeneic proliferation capacity than imDC and the secretion of IL-12p70 of TGFβ-DC was significantly less than that of imDC.

Zhang et al.(2002) discovered that TLR4 could activate nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) of DC, and then trigger the transcription of several cytokines, such as IL-1, IL-6, and IL-8; up-regulation of CMs, and enhance ability to activate T cells. We found that the expression of TLR4 mRNA in TGFβ-DC was weaker than that in imDC by means of semi-quantitative RT-PCR. This may explain why TGFβ-DC did not easily respond to LPS. It was reported recently that in a similar study, human monocyte-derived Langerhans cells did not respond to LPS because of non-expression of TLR4 (Takeuchi et al., 2003). The precise mechanism of feeble expression for TLR4 in the TGFβ-DC remains to be elucidated, although TGF-β1 may be involved in such impairment.

CONCLUSION

Our results showed strong inhibitory effect of TGF-β1 on DC differentiation and maturation, resulting in cells having reduced T cell stimulatory capacity, increased resistance to maturation stimulus (LPS) in culture and impaired IL-12p70 production. Further experiment of the in vivo function of TGFβ-DC in relation to their potential regulator influence on graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) is underway.

Footnotes

Project supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 30270571) and Doctor Degree Point Foundation of Ministry of Education, China (No. 20020335080)

References

- 1.Banchereau J, Steinman RM. Dendritic cells and the control of immunity. Nature. 1998;392:245–252. doi: 10.1038/32588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berer A, Stockl J, Majdic O, Wagner T, Kollars M, Lechner K, Geissler K, Oehler L. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 inhibits dendritic cell differentiation and maturation in vitro. Exp. Hematol. 2000;28:575–583. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(00)00143-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hackstein H, Morelli AE, Thomson AW. Designer dendritic cells for tolerance induction: guided not misguided missiles. Trends. Immunol. 2001;22:437–442. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(01)01959-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hirano A, Luke PP, Specht SM, Fraser MO, Takayama T, Lu L, Hoffman R, Thomson AW, Jordan ML. Graft hyporeactivity induced by immature donor-derived dendritic cells. Transpl. Immunol. 2000;8:161–168. doi: 10.1016/s0966-3274(00)00022-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jonuleit H, Schmitt E, Steinbrink K, Enk AH. Dendritic cells as a tool to induce anergic and regulatory T cells. Trends. Immunol. 2001;22:394–400. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(01)01952-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu T, Matsuguchi T, Tsuboi N, Yajima T, Yoshikai Y. Differences in expression of toll-like receptors and their reactivities in dendritic cells in BALB/c and C57BL/6 mice. Infect. Immun. 2002;70:6638–6645. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.12.6638-6645.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kadowaki N, Ho S, Antonenko S, Malefyt RW, Kastelein RA, Bazan F, Liu YJ. Subsets of human dendritic cell precursors express different toll-like receptors and respond to different microbial antigens. J. Exp. Med. 2001;194:863–869. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.6.863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Min WP, Gorczynski R, Huang XY, Kushida M, Kim P, Obataki M, Lei J, Suri RM, Cattral MS. Dendritic cells genetically engineered to express Fas ligand induce donor-specific hyporesponsiveness and prolong allograft survival. J. Immunol. 2000;164:161–167. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.1.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moustakas A, Pardali K, Gaal A, Heldin CH. Mechanisms of TGF-beta signaling in regulation of cell growth and differentiation. Immunol. Lett. 2002;82:85–91. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2478(02)00023-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Steinbrink K, Wolfl M, Jonuleit H, Knop J, Enk AH. Induction of tolerance by IL-10-treated dendritic cells. J. Immunol. 1997;159:4772–4780. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Steinman RM, Hawiger D, Nussenzweig MC. Tolerogenic dendritic cells. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2003;21:685–711. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Takeuchi J, Watari E, Shinya E, Norose Y, Matsumoto M, Seya T, Sugita M, Kawana S, Takahashi H. Down-regulation of Toll-like receptor expression in monocyte-derived Langerhans cell-like cells: implications of low-responsiveness to bacterial components in the epidermal Langerhans cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2003;306:674–679. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)01022-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang H, Tay PN, Cao W, Li W, Lu J. Integrin-nucleated Toll-like receptor (TLR) dimerization reveals subcellular targeting of TLRs and distinct mechanisms of TLR4 activation and signaling. FEBS. Lett. 2002;532:171–176. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03669-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]