Abstract

In human parturition, uterotonic prostaglandins (PGs) arise predominantly via increased expression of cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2 [also known as prostaglandin synthase 2]) within intra-uterine tissues. Interleukin-1 (IL-1) and epidermal growth factor (EGF), both inducers of COX-2 transcription, are among numerous factors that accumulate within amniotic fluid with advancing gestation. It was previously demonstrated that EGF could potentiate IL-1β-driven PGE2 production in amnion and amnion-derived (WISH) cells. To define the mechanism for this observation, we hypothesized that EGF and IL-1β might exhibit synergism in regulating COX-2 gene expression. In WISH cells, combined treatment with EGF and IL-1β resulted in a greater-than-additive increase in COX-2 mRNA relative to challenge with either agent independently. Augmentation of IL-1β-induced transactivation by EGF was not observed in cells harboring reporter plasmids bearing nuclear factor-kappa B (NFκB) regulatory elements alone, but was evident when a fragment (−891/+9) of the COX-2 gene 5′-promoter was present. Both agents transiently activated intermediates of multiple signaling pathways potentially involved in the regulation of COX-2 gene expression. The 26 S proteasome inhibitor, MG-132, selectively abrogated IL-1β-driven NFκB activation and COX-2 mRNA expression. Only pharmacologic blockade of the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase eliminated COX-2 expression following EGF stimulation. We conclude that EGF and IL-1β appear to signal through different signaling cascades leading to COX-2 gene expression. IL-1β employs the NFκB pathway predominantly, while the spectrum of EGF signaling is broader and includes p38 kinase. The synergism observed between IL-1β and EGF does not rely on augmented NFκB function, but rather, occurs through differential use of independent response elements within the COX-2 promoter.

Keywords: cytokines, growth factors, parturition, placenta, signal transduction

INTRODUCTION

There is abundant evidence supporting a critical role for prostaglandins (PGs) in the onset and maintenance of human parturition, both at and before term. In what has been proposed as the final common pathway for labor, increased production of PGE2 and PGF2α by intrauterine tissues facilitates cervical ripening, fetal membrane rupture, and the development of myometrial contractions [1]. Cyclooxygenase (COX) isoforms catalyze the committed and rate-limiting step in PG production [2]. COX-1 is constitutively present in many tissues and contributes to low-amplitude PG release, whereas transient expression of the inducible COX-2 (also known as prostaglandin synthase 2) isoform is required for high-amplitude PG production [2]. In the context of parturition, the majority of PGs elaborated by intrauterine tissues arise through increased de novo expression of COX-2, which is controlled primarily at the transcriptional level [3].

Although it has been theorized that term parturition results from a localized inflammatory process, current evidence suggests this reaction is modest [4]. While it is true that inflammatory cytokines (interleukin-1 [IL-1], IL-6, IL-8, and tumor necrosis factor [TNF]) increase within amniotic fluid toward term in normal pregnancies [5] and that these factors themselves are capable of stimulating COX-2 expression and PG production [6–8], it is unlikely that these agents work in isolation. Numerous factors capable of increasing COX-2 expression accumulate within the amniotic fluid with advancing gestation [1, 5]. It has been hypothesized that factors originating from the mature fetus (such as epidermal growth factor [EGF] or its close structural relative, transforming growth factor-α) may act cooperatively with substances produced by fetal membranes and maternal decidua to control the robust elaboration of PGs, which precedes and accompanies term labor [9–11].

It has previously been demonstrated that EGF potentiates IL-1β-driven PGE2 production in amnion and amnion-derived cells [11, 12]. To define the mechanism for this observation, it was hypothesized that EGF and IL-1β might exhibit synergism in regulating COX-2 gene expression. Here, we report on the transcriptional regulation of COX-2 following single-agent or combined challenge with IL-1β and EGF and examine the signaling mechanisms employed by these factors.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Recombinant human EGF and IL-1β were purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). The antibody detecting glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was purchased from Chemicon International (Temecula, CA). Antibodies against inhibitory factor-κBα (IκBα), nuclear factor-kappa B (NFκB) subunit p65, IκB kinase (IKK)α/β, c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), extracellular-regulated kinase-2 (Erk-2), signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3), and STAT5 were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Antibodies recognizing phospho-IκBα(Ser32), phospho-IKKα(Ser180)/IKKβ(Ser181), STAT1, phospho-STAT1 (Tyr701), phospho-STAT3 (Tyr705), and phopho-STAT5 (Tyr694) were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA). Antibodies against phospho-Erk-1/Erk-2 (Thr183/Tyr185), phospho-JNK (Thr183/Tyr185), p38 mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase, and phospho-p38 MAP kinase (Thr180/Tyr 182) were from Promega (Madison, WI), as were the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System and the Renilla luciferase control expression vector (pRL-SV40). The peptide aldehyde 26 S proteasome inhibitor MG-132, the p38 inhibitor SB-202190, the Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor AG-490, and the MAP/Erk kinase (MEK) inhibitor PD-98059 were obtained from BIOMOL (Plymouth Meeting, PA). The JNK inhibitor SP-600125 was purchased from Tocris (Ballwin, MO). The 1.8-kilobase (kb) cDNA fragment encoding human COX-2 used as a probe for Northern blotting was a kind gift from Dr. Timothy Hla (University of Connecticut, Farmington, CT). The firefly luciferase reporter plasmid containing a segment (−891/+9) of the human COX-2 promoter (pPGS891LUC) was generously donated by Dr. Lee Ho Wang (University of Texas, Houston, TX) [13]. The PathDetect NFκB-firefly luciferase reporter plasmid (pNFκB-Luc) was obtained from Stratagene (La Jolla, CA). TRIzol, Lipofectin, and PLUS reagents were obtained from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Hybond-N+ nylon and Hybond-C Extra nitrocellulose membranes were from Amersham Biosciences (Piscataway, NJ). Digoxigenin (DIG) Nucleic Acid Detection and DIG-High Prime kits were purchased from Roche Diagnostics (Indianapolis, IN). SuperSignal chemiluminescent substrate was obtained from Pierce Biotechnology (Rockford, IL). ProLong Antifade mounting reagent and Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibodies were obtained from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR). Other reagents were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO)

Cell Culture

Human amnion-derived (WISH) cells [14] were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC CCL-25) and maintained in Ham F-12/Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (Invitrogen, Gaithersburg, MD) supplemented with 2 mM l-glutamine, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, and 10% newborn calf serum. Cells were grown at 37°C in an atmosphere of 95% air/5% CO2 and used for experiments between the 3rd and 25th passages. All cultures were serum-starved overnight before experiments.

Northern Blot Analysis

Following experiments, total RNA was extracted using TRIzol (Invitrogen). RNA (20 μg/lane) was fractionated on a 1% (w/v) agarose gel containing 2% (v/v) formaldehyde and transferred to a nylon membrane by downward capillary elution. Membranes were analyzed by hybridization to DIG-containing COX-2 and GAPDH cDNA probes, labeled using the DIG-High Prime kit (Roche). Blots were probed overnight at 42°C in hybridization buffer (7% [w/v] SDS, 50% [v/v] formamide, 325 mM sodium chloride, 32.5 mM sodium citrate, 50 mM sodium phosphate [pH 7.0], 0.1% [w/v] N-lauroylsarcosine, 50 μg/ml sheared salmon sperm DNA, and 2% [w/v] DIG Blocking Reagent [Roche]). Bound probes were identified using the DIG Nucleic Acid Detection kit (Roche). Chemiluminescent signals were detected using the VersaDoc Imaging System and analyzed using Quantity One software (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA).

Immunoblotting

Cellular proteins were extracted and prepared for immunoblotting as previously described [15]. Proteins (30 μg/lane) were resolved by electrophoresis on SDS/10% (w/v) polyacrylamide gels, transferred to nitrocellulose, and probed with antibodies directed against phosphorylated signaling intermediates of the NFκB, JAK/STAT, and MAP kinase signal transduction pathways. Conditions for immunoblotting were established by a manufacturer’s suggested protocol (Cell Signaling Technology). Immunoreactivity was detected using SuperSignal chemiluminescent substrate (Pierce Biotechnology) and detected using the VersaDoc Imaging System (Bio-Rad Laboratories).

Immunofluorescence

WISH cells were seeded onto flame-sterilized 12-mm2 glass coverslips placed in a 24-well tissue culture plate. Following treatments, cells were fixed for 1 h in 4% (w/v) paraformaldehyde/PBS, made permeable by the addition of 0.2% (v/v) Triton X-100/PBS for 15 min, and blocked in 5% (v/v) horse serum/PBS overnight at 4°C before the addition of antibodies. Monoclonal antibodies directed against p65 (Santa Cruz) were then applied. After stringent washing in PBS, the coverslips were exposed to fluorochrome-conjugated secondary antibodies (Molecular Probes). Following a second series of washes, cells were mounted using the ProLong Antifade kit (Molecular Probes) and visualized using an epifluorescence microscope (Nikon Instruments, Melville, NY).

Transient Transfection and Luciferase Assays

Transient transfections were performed in a 24-well tissue culture plate seeded at 5 × 104 cells per well. For each cotransfection, 0.6 μg of reporter plasmid (pNFκB-Luc or pPGS891LUC), 0.1 μg control plasmid (pRL-SV40), 0.6 μl Lipofectin reagent (Invitrogen), and 5 μl PLUS reagent (Invitrogen) were used, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Luciferase assays were performed using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega) and a Dynex MLX Microplate Luminometer (Dynex Technologies, Chantilly, VA). Reporter activity was expressed as the ratio of firefly luciferase activity (pNFκB-Luc or pPGS891LUC) to Renilla luciferase activity (pRL-SV40).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad InStat software version 3.06 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA), employing one-way ANOVA and the Tukey-Kramer multiple comparisons test. A P value of 0.05 or less was considered significant.

RESULTS

EGF and IL-1β Synergistically Upregulate COX-2 mRNA Expression

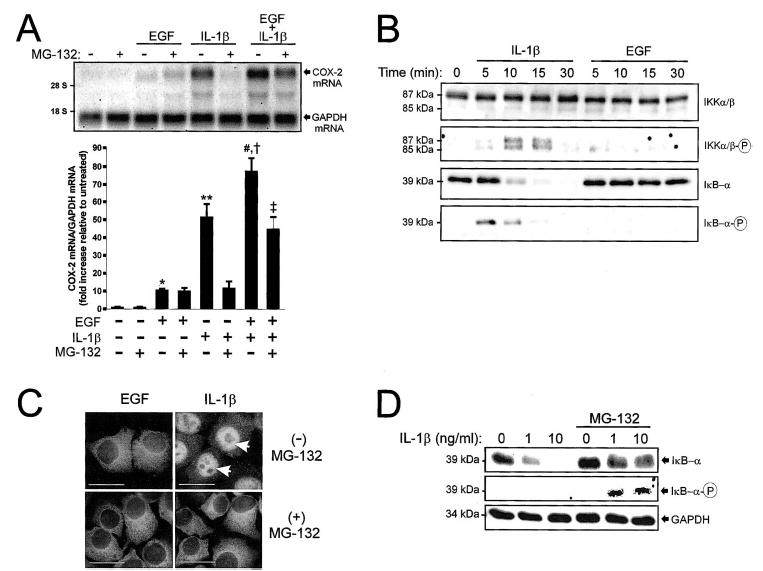

The expression of COX-2 mRNA in WISH cells 1 h following challenge with EGF (10 ng/ml), IL-1β (10 ng/ ml), or both was examined. Relative to untreated cells, incubation with EGF elicited a modest 11-fold increase in COX-2 mRNA expression on average (Fig. 1A). The response to IL-1β was more robust, with an average 52-fold increase in COX-2 mRNA compared with untreated cells (Fig. 1A). Interestingly, we found that coincubation with EGF and IL-1β resulted in an average 78-fold increase in COX-2 mRNA. The response to combined challenge was significantly greater than treatment with either factor independently (P < 0.001 vs. EGF, P < 0.05 vs. IL-1β), suggesting synergy between EGF and IL-1β in regulating COX-2 gene expression.

FIG. 1.

Effects of EGF and IL-1β on NFκB activation and COX-2 mRNA expression. A) Northern blots were prepared from WISH cell lysates 1 h following individual or combined challenge with EGF (10 ng/ml) and IL-1β (10 ng/ml) in the presence or absence of MG-132 (30 μM). COX-2 mRNA was detected using a UTP-DIG-labeled 1.8-kb cDNA encoding human COX-2. Chemiluminescent detection of COX-2 mRNA (4.5-kb band) was quantified by densitometric scanning. The amount of COX-2 mRNA in the absence of EGF, IL-1β, and MG-132 was set to 1. Data were normalized to GAPDH mRNA levels in each treatment group, standardized in relation to the control (untreated) group, and represented graphically (mean ± SEM, n = 3 individual experiments). *, P < 0.05 vs. untreated; **, P < 0.001 vs. untreated; #, P < 0.001 vs. EGF; †, P < 0.05 vs. IL-1β; ‡, P < 0.01 vs. EGF/ IL-1β combined (ANOVA). B) Cells were treated with IL-1β or EGF for 0–30 min and prepared for immunoblot analysis. Activation of NFκB was assessed using antibodies detecting phosphorylated and nonphosphorylated forms of IKKα (85 kDa), IKKβ (87 kDa), and IκB-α (39 kDa). C) Intracellular localization of NFκB subunit p65 was detected by immunofluorescence in cells treated with EGF or IL-1β for 15 min in the presence or absence of MG-132. Arrows denote nuclear localization of p65 in the presence of IL-1β alone. Bars = 20 μm. D) Immunoblots were prepared from cells treated for 15 min with 0–10 ng/ml IL-1β in the presence or absence of MG-132 and probed with antibodies detecting either total IκB-α (top panel) or phosphorylated IκB-α (Ser32, bottom panel).

Blockade of NFκB Selectively Attenuates IL-1β-Induced COX-2 mRNA Expression

Like other proinflammatory cytokines, IL-1β has been demonstrated to use the NFκB cascade for COX-2 gene induction [6, 16, 17]. EGF also has been shown to elicit NFκB activation in certain cell types [18, 19]. NFκB exists as a dimer of Rel family proteins (prototypically p65/p50 or p50/p50) bound to an inhibitor (IκB-α) [20]. In the presence of IκB-α, the net intracellular distribution of the NFκB complex is almost entirely cytoplasmic [20]. When activated, IκB-α is phosphorylated by IκB kinases (IKKs) at two N-terminal serinyl residues (Ser32 and Ser36), triggering ubiquitylation and subsequent degradation of this inhibitor by the 26 S proteasome [21]. Through this mechanism, NFκB nuclear localization signals are exposed and nuclear migration affords access of this transcription factor to κB response elements.

To assess NFκB activation, WISH cells in confluent monolayer culture were treated with IL-1β (10 ng/ml) or EGF (10 ng/ml) and harvested for immunoblot analysis from 0 to 30 min. IL-1β elicited activation of IKKα and IKKβ, as evidenced by transient phosphorylation at serinyl residues 180 of IKKα and 181 of IKKβ (Fig. 1B). This occurred concomitantly with phosphorylation of IκB-α at serinyl residue 32. The time-dependent loss of immunoreactive IκB-α between 10 and 30 min followed its site-specific phosphorylation (present at 5 min) and was consistent with proteasome-mediated degradation. By immunofluorescence, nuclear translocation of the NFκB subunit p65 was seen 15 min following IL-1β challenge (Fig. 1C, arrows). In contrast, EGF did not elicit activation of IKKα or IKKβ, and no phosphorylation or degradation of IκB-α was discerned (Fig. 1B). Furthermore, we detected no net nuclear translocation of p65 in response to EGF (Fig. 1C).

Use of the 26 S proteasome inhibitor MG-132 (N-acetyl leucinyl-leucinyl-leucinal) prohibits degradation of phosphorylated IκB-α and prevents NFκB-mediated transcriptional activation [21, 22]. When WISH cells were preincubated with MG-132 (30 μM) before IL-1β challenge, loss of IκB-α immunoreactivity at 15 min was blocked (Fig. 1D). The presence of nondegraded, phosphorylated IκB-α in these lanes was demonstrated by probing with a phospho-specific antibody (Fig. 1D). By immunofluorescence, it was confirmed that MG-132 prevented IL-1β-induced nuclear translocation of the NFκB subunit p65 (Fig. 1C). COX-2 mRNA expression induced by IL-1β was attenuated by 77% in the presence of MG-132 (Fig. 1A). In contrast, MG-132 had no effect on EGF-driven COX-2 expression. Additionally, it was observed that MG-132 reduced COX-2 mRNA expression by only 42% in response to combined EGF/IL-1β challenge (Fig. 1A). The expression of COX-2 mRNA following combined treatment with IL-1β, EGF, and MG-132 was consistently greater than that observed in response to EGF alone, suggesting that signaling mechanisms other than NFκB may contribute to EGF/IL-1β cooperativity. Collectively, these results suggest that IL-1β-mediated COX-2 gene expression is reliant on signaling through NFκB, while additional transduction mechanisms are required for COX-2 induction following EGF or combined EGF/IL-1β treatment.

Multiple Response Elements Are Required for Cooperative Increases in COX-2 Promoter Activity Following Combined EGF/IL-1β Treatment

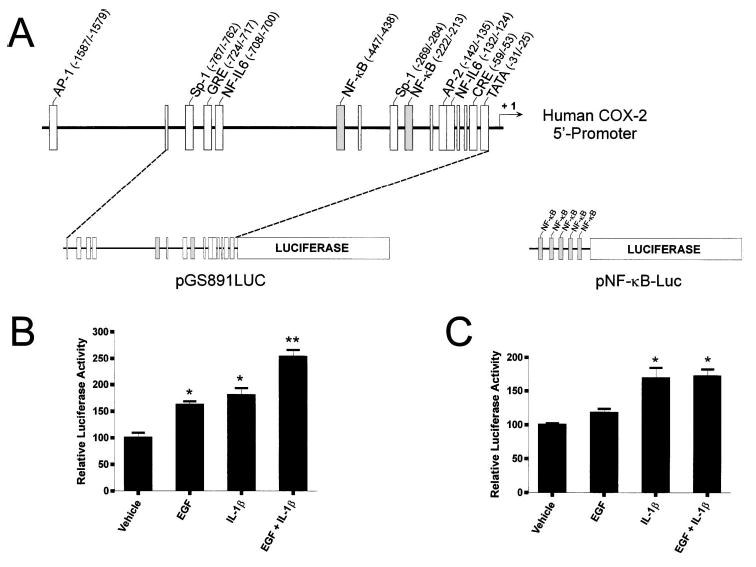

Analysis of the 5′-promoter region of the human COX-2 gene has revealed several potential transcription factor binding sequences, including those for NFκB, nuclear factor-interleukin-6 (NF-IL6; also known as CCAAT/enhancer binding protein, C/EBP), activator protein-1 (AP-1), cyclic adenosine monophosphate response element binding protein (CREB), and the glucocorticoid receptor (Fig. 2A) [13, 23]. To examine the effects of EGF and IL-1β on COX-2-promoter activity, cells were transiently transfected with a luciferase reporter plasmid containing a segment (−891/+9) of the human COX-2 promoter (pPGS891LUC) [13]. This region contains many of the well-characterized transcription factor response elements (including CRE and two κB motifs) but does not contain the AP-1 response element located −1587/−1579 base pairs (bp) upstream of the transcriptional start site (Fig. 2A) [23]. In cells transfected with pPGS891LUC, EGF (10 ng/ml) elicited an average 62% increase in reporter activity relative to untreated cells (P < 0.01; Fig. 2B). The response to IL-1β (10 ng/ml) was only slightly greater, with an 80% increase in reporter activity on average relative to control cells (P < 0.01; Fig. 2B). Combined challenge with IL-1β and EGF produced a cooperative (153%) increase in luciferase activity relative to untreated cells (P < 0.001; Fig. 2B).

FIG. 2.

Individual and combined effects of EGF and IL-1β on COX-2 promoter-dependent luciferase expression. A) Diagram showing enhancer elements located within the human COX-2 5′-promoter, pPGS891LUC, and pNFκB-Luc. The two κB regulatory elements within the human COX-2 5′-promoter (located at −447/−438 bp and −222/−213 bp upstream of the transcriptional start site) are depicted in gray boxes. NFκB, Nuclear factorκB response element; NF-IL6, nuclear factor-interleukin-6 response element; AP-1, activator protein-1 response element; CRE, cAMP response element; GRE, glucocorticoid receptor response element; Sp-1, selective promoter factor-1 response element; AP-2, activating protein-2 response element; TATA, TATA box. Based on data by Tazawa et al. [13] and Allport et al. [23]. B, C) Cells were transiently transfected with pPGS891LUC [13] or pNFκB-Luc [28]. Twenty-four h after transfection, cells were treated with EGF (10 ng/ml), IL-1β (10 ng/ml), or both for 4 h and then processed. Firefly luciferase activity was normalized to Renilla luciferase activity in each lysate. Each bar represents the mean ± SEM of four replicates from two experiments. *, P < 0.01 vs. control; **, P < 0.001 vs. control (ANOVA).

To ascertain whether the combined effects of IL-1β and EGF could be explained by augmented κB-dependent transactivation, cells were transiently transfected with a luciferase reporter construct linked with five tandem repeats of the κB response element (pNFκB-Luc, Stratagene; Fig. 2A). In cells harboring pNFκB-Luc, increased reporter activity was observed only in response to IL-1β (P < 0.01 vs. control; Fig. 2C). This response was not augmented by coincubation with EGF (Fig. 2C). These results suggest that synergism between IL-1β and EGF does not rely on increased NFκB function, but rather, may occur through differential use of independent cis-acting response elements within the COX-2 promoter.

EGF and IL-1β Transiently Activate Multiple Signal Transduction Pathways

Given that multiple response elements appear necessary for EGF/IL-1β cooperativity, we next sought supplementary transduction mechanisms whereby these factors may increase COX-2 gene expression. In addition to NFκB, IL-1β has been shown to activate the three major MAP kinase pathways: p38 MAP kinase, extracellular-regulated kinases-1 and -2 (Erk-1/Erk-2), and c-Jun N-terminal kinases (JNK) [24]. Activation of the MAP kinase signaling pathways, particularly JNK and p38, can induce COX-2-promoter activity through recruitment of transcription factors to AP-1 and CRE consensus sequences [25, 26]. The signaling pathways governing COX-2 gene expression in response to EGF in WISH cells have not been clearly established. Based on other model systems, these may include the JAK/ STAT and/or MAP kinase cascades [27–29]. Although response elements to STATs within the human COX-2 5′-promoter have not been described, activated STATs have been shown to modulate the effects of other transcription factors relevant to the control of COX-2 gene activation [30, 31].

WISH cells were treated with IL-1β (10 ng/ml) or EGF (10 ng/ml) and harvested for immunoblot analysis at time points from 0 to 30 min. Additionally, to examine whether activation of these cascades was altered in response to combination treatment, cells challenged with EGF and IL-1β individually or together were harvested at a single point (12.5 min postchallenge). Activation of signaling intermediates was assessed through immunodetection of transiently phosphorylated intermediates.

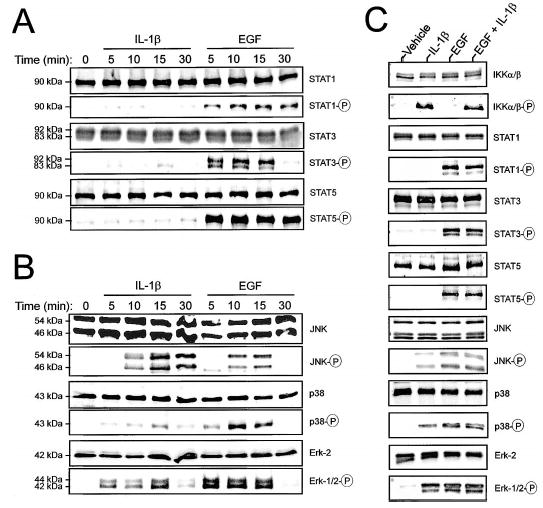

Treatment with EGF, but not IL-1β, resulted in phosphorylation of STAT1, STAT3, and STAT5 (Fig. 3A). Both EGF and IL-1β caused transient phosphorylation of p38, JNK isoforms (JNK1 and -2), and Erk-1/Erk-2 (Fig. 3B). Across experiments, phosphorylation of p38 and Erk-1/Erk-2 was consistently greater following EGF treatment relative to stimulation with IL-1β. Phosphorylation of JNK was more robust in response to IL-1β at later time points (15 and 30 min), whereas at earlier time points (5 and 10 min), it was greater in response to EGF. Following combined EGF/IL-1β treatment, there was no discernible potentiation of the amount of phosphorylated signaling intermediates among those examined at 12.5 min (Fig. 3C).

FIG. 3.

Activation of JAK/STAT and MAP kinase signaling intermediates following challenge with IL-1β or EGF. A, B) Cells were treated with IL-1β (10 ng/ml) or EGF (10 ng/ml) for 0–30 min and prepared for immunoblot analysis. Activation of the JAK/STAT signaling cascade was assessed by probing with antibodies recognizing total and phosphorylated forms of STAT1 (90 kDa), STAT3 (83 and 92 kDa), and STAT5 (90 kDa). Activation of the major MAP kinase signaling cascades (B) was assessed using antibodies recognizing total Erk-2 (42 kDa), dually phosphorylated Erk-1 (44 kDa)/Erk-2 (42 kDa), total and phosphorylated p38 (43 kDa), and total and phosphorylated JNK-1 (46 kDa)/JNK-2 (54 kDa). C) Cells were treated with EGF and IL-1β individually or in combination for 12.5 min and prepared for immunodetection of activated signaling intermediates. These blots are representative of four independent experiments.

Inhibition of p38 MAP Kinase Eliminates EGF-Induced COX-2 mRNA Expression

Activation of Erk-1/Erk-2, JNK, and p38 precedes EGF-and IL-1β-mediated COX-2 induction. Additionally, activation of STAT isoforms occurs acutely following EGF stimulation. To investigate the relationship of these cascades to COX-2 mRNA expression, the effects of specific pharmacological inhibitors on this process were investigated. Cells were pretreated for 1 h in the presence of 50 μM AG-490 (JAK/STAT pathway inhibitor [32]), 30 μM SB-202190 (p38 MAP kinase inhibitor [33]), 30 μM SP600125 (JNK inhibitor [34]), or 45 μM PD-98059 (MEK/Erk-1/ Erk-2 pathway inhibitor [35]) before challenge with EGF or IL-1β (both at 10 ng/ml). Control cells received 0.8% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, vehicle for AG-490, SB-202190, and PD-98059) or 0.6% ethanol (ETO, vehicle for SP600125) in the presence or absence of EGF or IL-1β. Cells were harvested 1 h following challenge and COX-2 mRNA expression was detected by Northern blot analysis.

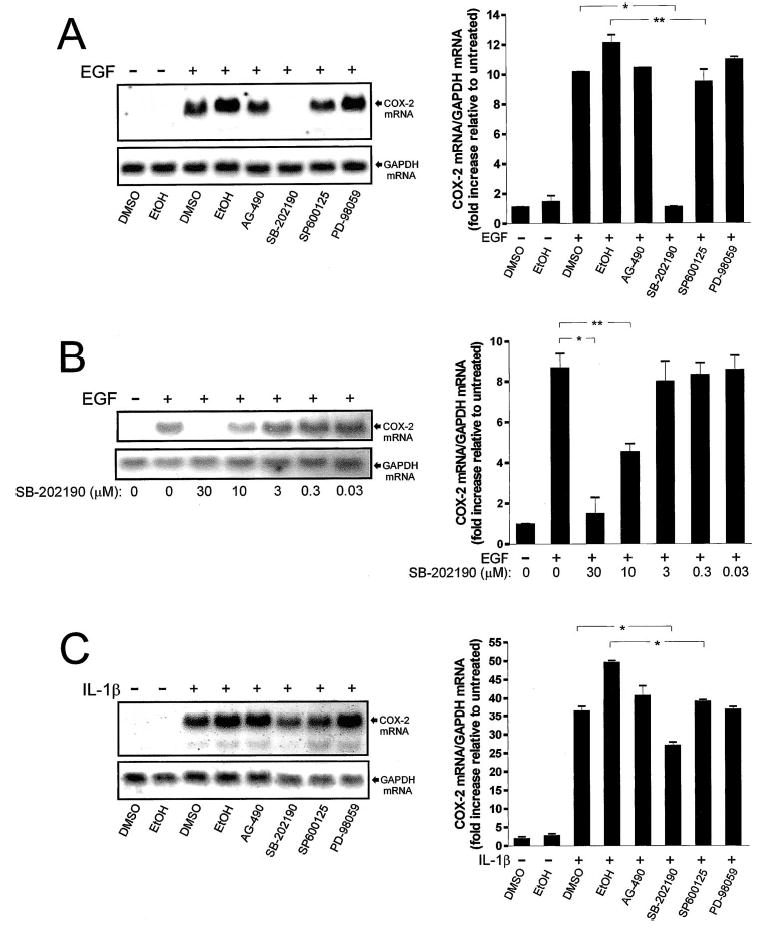

The expression of COX-2 mRNA in cells stimulated with EGF was blocked by SB-202190 (P < 0.01; Fig. 4A). SP600125 also had a small but discernible effect on EGF-induced COX-2 mRNA accumulation relative to its vehicle control group (P < 0.05; Fig. 4A). The other agents (AG-490 and PD-98059) were without significant effect, even at the relatively high doses used. The effect of SB-202190 on EGF-induced COX-2 mRNA expression was dose dependent (Fig. 4B). Complete blockade of COX-2 expression occurred only at concentrations of 30 μM or greater. At 10 μM, EGF-induced COX-2 expression was reduced by 48% on average, whereas doses 3 μM or below were without effect. IL-1β-stimulated COX-2 mRNA expression was modestly attenuated by both SB-202190 (average decrease of 26%, P < 0.01) and SP600125 (average decrease of 21%, P < 0.01) relative to their respective vehicle controls (Fig. 4C), whereas the other agents showed no effect. Across experiments, it was noted that the DMSO-treatment group showed discernibly decreased COX-2 induction relative to cells exposed to EtOH, implying a slight vehicle effect (Fig. 4, A and C). By visual inspection through phase-contrast microscopy, there was no evidence of cytotoxicity in any of the treatment groups. These results indicate that p38 MAP kinase activity may contribute most substantially to EGF-driven COX-2 mRNA expression in WISH cells, although a minor role for JNK MAP kinase in this process is suggested. Furthermore, although NFκB appears to be the major transduction mechanism through which IL-1β induces COX-2 expression, these results suggest that downstream effectors of the JNK and p38 MAP kinases might also contribute. These results have been summarized in Figure 5.

FIG. 4.

Effect of pharmacological inhibition of MAP kinase and JAK/STAT signaling cascades on EGF- and IL-1β-driven COX-2 mRNA expression. A) Representative Northern blot demonstrating COX-2 mRNA levels 1 h following treatment with vehicles alone (0.6% EtOH, 0.8% DMSO), vehicles with EGF (10 ng/ml), or EGF in the presence of AG-490 (50 μM), SB-202190 (30 μM), SP600125 (30 μM), or PD-98059 (45 μM). Chemiluminescent detection of COX-2 mRNA (4.5-kb band) was quantified by densitometric scanning. Data were normalized to GAPDH mRNA levels in each treatment group, standardized in relation to the control (untreated) group, and represented graphically. At the settings chosen for presentation, the low levels of basal COX-2 mRNA expression in these Northern blots are not readily discerned. B) Representative Northern blot demonstrating COX-2 mRNA levels 1 h following treatment with vehicle alone (0.8% DMSO), vehicle with EGF, or EGF in the presence 0.03–30 μM SB-202190. C) Representative Northern blot and densitometric analysis demonstrating COX-2 mRNA levels 1 h following treatment with vehicles alone (0.6% EtOH, 0.8% DMSO), vehicles with IL-1β (10 ng/ml), or IL-1β in the presence of AG-490 (50 μM), SB-202190 (30 μM), SP600125 (30 μM), or PD-98059 (45 μM). Each bar represents the mean ± SEM for two or three individual experiments, which were run in duplicate. *, P < 0.01 vs. indicated treatment group; **, P < 0.05 vs. indicated treatment group.

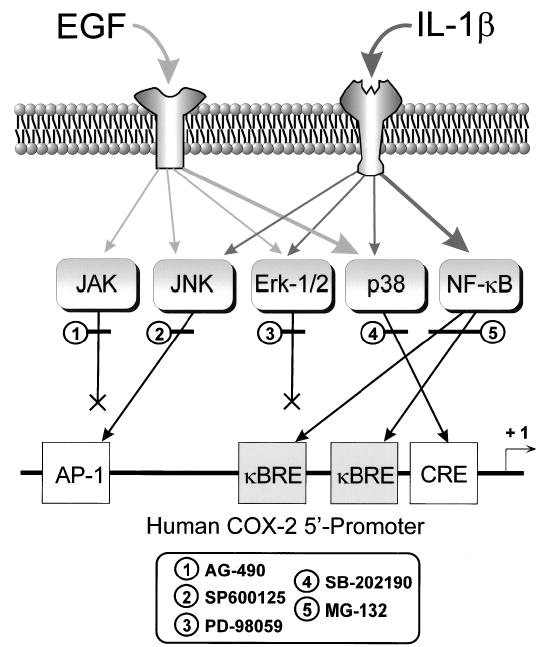

FIG. 5.

Schematic diagram of signaling pathways activated by EGF and IL-1β to upregulate COX-2 mRNA expression in amnion-derived WISH cells. Pathways used by EGF are depicted by light gray arrows, while those activated by IL-1β are depicted by dark gray arrows. Major signaling pathways activated by each agent are represented by the larger arrows. Target response element within the COX-2 5′-promoter region that are potentially employed by these signaling cascades are shown, as are the sites of action of the pharmacological inhibitors used in this study. κBRE, Nuclear factorκB response element; AP-1, activator protein-1 response element; CRE, cAMP response element.

DISCUSSION

The simultaneous accumulation of cytokines and growth factors in amniotic fluid at term has led to the concept that these agents may act cooperatively to enact events requisite to parturition [11, 12]. COX-2, which is present at very low levels in amnion during the majority of gestation but is highly expressed toward term, drives the rate-limiting step in PG production [2]. In this study, it was determined that EGF and IL-1β can synergistically increase COX-2 mRNA expression in amnion-like WISH cells. This is a plausible mechanism through which EGF (derived primarily from the maturating fetus) could supplement the effects of cytokines (generated by a limited inflammatory response at the maternal-fetal interface) to increase intrauterine PG output necessary for successful labor [4, 11, 12].

Combined EGF/IL-1β stimulation resulted in summative effects on COX-2 promoter activity, suggesting that cooperative increases in COX-2 mRNA expression are governed, at least in part, by enhanced COX-2 transcription. It is quite likely that IL-1β-induced COX-2 mRNA accumulation results both from increased transcription as well as posttranscriptional mRNA stabilization [16, 36, 37]. The contribution of increased mRNA stability to COX-2 mRNA expression following combined EGF/IL-1β treatment was not assessed in the present study. We speculate that increased mRNA stability may be an additional mechanism through which EGF potentiates IL-1β-induced COX-2 mRNA expression.

In previous studies, it was shown that human COX-2 promoter constructs bearing mutations in one or both of the NFκB sites had reduced reporter activity following IL-1β stimulation in WISH cells [23, 37]. In this report, it was demonstrated that treatment with the 26 S proteasome inhibitor MG-132 blocked NFκB activation and significantly attenuated IL-1β-induced COX-2 mRNA expression in WISH. These results support NFκB as a prominent signaling mechanism for IL-1β-induced COX-2 mRNA expression. However, it was noted that MG-132 failed to completely attenuate IL-1β-driven COX-2 mRNA expression. Although the residual COX-2 mRNA seen in this case could have been due to incomplete inhibition of the 26 S proteasome, our results suggest that additional transcription factors are likely to contribute to cytokine-induced COX-2 gene expression. Pharmacological inhibition of the both the p38 and JNK signaling pathways modestly abrogated IL-1β-driven COX-2 expression. This is consistent with previous reports, in which a role for AP-1-binding transcription factors (including those activated by p38 and JNK) in IL-1β-mediated COX-2 gene expression was suggested [23, 37].

The signaling pathways mediating EGF-induced COX-2 gene expression in WISH cells have not been clearly delineated, although the MAP kinase cascades have been implicated [29]. Our results suggest that EGF-mediated COX-2 mRNA expression in WISH cells does not require activation of NFκB. Pharmacological blockade of p38 MAP kinase activity abrogated EGF-stimulated COX-2 gene expression in a dose-dependent fashion. These data are intriguing, particularly in light of the possible role for activated p38 in the process of term parturition in mice has been demonstrated [38]. For these experiments, the potent and selective p38 MAP kinase inhibitor SB-202190 was used. This agent has been employed widely to parse the physiological functions of p38 [33, 39]. In terms of specificity, previous studies have reported that SB-202190 does not inhibit other MAP kinases, such as JNK or Erk-1/Erk-2, even at concentrations as high as 100 μM [33, 39]. However, it is possible that nonspecific effects of this agent could have contributed to our findings. Further studies are needed to corroborate these results. Additionally, it was noted that blockade of JNK isoforms had a limited effect on EGF-mediated COX-2 mRNA expression, suggesting that JNK activation might also contribute to this process. Contrary to a previous report [29], we found no evidence that the MEK/Erk pathway was involved in EGF-dependent COX-2 mRNA expression. It remains unclear what downstream effectors of the p38 and JNK kinases might be important for EGF-mediated COX-2 transcriptional upregulation. We speculate that transcription factors activated by a p38-dependent mechanism (such as ATF-2 or C/EBP) might drive COX-2 transcription through CRE and/or NF-IL6 response elements within the proximal promoter [40, 41]. Additionally, activation of p38 could also contribute to COX-2 mRNA stability [42].

The signaling cascades responsible for EGF/IL-1β synergism in COX-2 transcription are likely to be more complex than those required for either agent separately. Our current data suggest that COX-2 gene expression in response to combined challenge is only partially dependent on NFκB. Furthermore, augmentation of IL-1β-induced NFκB activity by EGF does not appear to be a mechanism through which this synergism occurs. Activation of the COX-2 promoter appears to require differential use of independent response elements located in the region spanning −891/+9 bp relative to the transcriptional start site. This is likely to involve the effectors of multiple signaling pathways (particularly NFκB, p38, and JNK), but may also stem from cooperativity among the activated signaling intermediates (e.g., STAT3 and AP-1 transcription factors can interact synergistically, even in the absence of a STAT3 enhancer element [43]), or cross-talk between EGF and IL-1 receptors [44]. Ongoing efforts in our laboratory will be aimed at further investigating the molecular mechanisms through which growth factor/cytokine cooperativity occurs.

We conclude that EGF and IL-1β appear to signal through different transduction cascades leading to COX-2 gene expression in WISH cells. While IL-1β employs the NFκB pathway predominantly, the spectrum of EGF signaling is broader and includes p38 kinase.

EGF and IL-1β act cooperatively to increase COX-2 mRNA expression, which is the likely basis for the greater-than-additive effects these agents have on PGE2 production [11, 12]. The synergism observed between IL-1β and EGF in COX-2 transcriptional activation does not rely on augmented NF-κB function, but rather, may occur through differential use of independent response elements within the COX-2 promoter.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Thanh M. Nguyen for conducting important studies in the early portions of this project. We gratefully acknowledge Dr. Xiaolan L. Zhang for her excellent technical support in conducting the luciferase assays. We thank Dr. Martha Belury for critical review of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Supported in part by NIH grant RO1 HD35881 (D.A.K.) and The Ohio State University Perinatal Research and Development Fund. Portions of this work were presented at the 49th Annual Meeting of the Society for Gynecologic Investigation in Los Angeles, California, March 20–23, 2002, and the 51st Annual Meeting of the Society for Gynecologic Investigation in Houston, Texas, March 24–27, 2004.

References

- 1.Kniss DA, Iams JD. Regulation of parturition update. Endocrine and paracrine effectors of term and preterm labor. Clin Perinatol. 1998;25:819–836. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kniss DA. Cyclooxygenases in reproductive medicine and biology. J Soc Gynecol Invest. 1999;6:285–292. doi: 10.1016/s1071-5576(99)00034-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnson RF, Mitchell CM, Giles WB, Walters WA, Zakar T. The in vivo control of prostaglandin H synthase-2 messenger ribonucleic acid expression in the human amnion at parturition. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:2816–2823. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.6.8524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Keelan JA, Blumenstein M, Helliwell RJ, Sato TA, Marvin KW, Mitchell MD. Cytokines, prostaglandins and parturition—a review. Placenta. 2003;24(suppl A):S33–S46. doi: 10.1053/plac.2002.0948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bowen JM, Chamley L, Keelan JA, Mitchell MD. Cytokines of the placenta and extra-placental membranes: roles and regulation during human pregnancy and parturition. Placenta. 2002;23:257–273. doi: 10.1053/plac.2001.0782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yan X, Wu XC, Sun M, Tsang BK, Gibb W. Nuclear factor kappa B activation and regulation of cyclooxygenase type-2 expression in human amnion mesenchymal cells by interleukin-1beta. Biol Reprod. 2002;66:1667–1671. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod66.6.1667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Albert TJ, Su HC, Zimmerman PD, Iams JD, Kniss DA. Interleukin-1 beta regulates the inducible cyclooxygenase in amnion-derived WISH cells. Prostaglandins. 1994;48:401–416. doi: 10.1016/0090-6980(94)90006-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Perkins DJ, Kniss DA. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha promotes sustained cyclooxygenase-2 expression: attenuation by dexamethasone and NSAIDs. Prostaglandins. 1997;54:727–743. doi: 10.1016/s0090-6980(97)00144-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Casey ML, MacDonald PC, Mitchell MD. Stimulation of prostaglandin E2 production in amnion cells in culture by a substance(s) in human fetal and adult urine. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1983;114:1056–1063. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(83)90669-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Casey ML, Korte K, MacDonald PC. Epidermal growth factor stimulation of prostaglandin E2 biosynthesis in amnion cells. Induction of prostaglandin H2 synthase. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:7846–7854. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kniss DA, Zimmerman PD, Fertel RH, Iams JD. Proinflammatory cytokines interact synergistically with epidermal growth factor to stimulate PGE2 production in amnion-derived cells. Prostaglandins. 1992;44:237–244. doi: 10.1016/0090-6980(92)90016-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bry K. Epidermal growth factor and transforming growth factor-alpha enhance the interleukin-1- and tumor necrosis factor-stimulated prostaglandin E2 production and the interleukin-1 specific binding on amnion cells. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 1993;49:923–928. doi: 10.1016/0952-3278(93)90177-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tazawa R, Xu XM, Wu KK, Wang LH. Characterization of the genomic structure, chromosomal location and promoter of human prostaglandin H synthase-2 gene. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994;203:190–199. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.2167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hayflick L. The establishment of a line (WISH) of human amnion cells in continuous cultivation. Exp Cell Res. 1961;23:14–20. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(61)90059-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Perkins DJ, Kniss DA. Rapid and transient induction of cyclo-oxygenase 2 by epidermal growth factor in human amnion-derived WISH cells. Biochem J. 1997;321:677–681. doi: 10.1042/bj3210677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Newton R, Kuitert LM, Bergmann M, Adcock IM, Barnes PJ. Evidence for involvement of NF-kappaB in the transcriptional control of COX-2 gene expression by IL-1beta. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;237:28–32. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Belt AR, Baldassare JJ, Molnar M, Romero R, Hertelendy F. The nuclear transcription factor NF-kappaB mediates interleukin-1beta-induced expression of cyclooxygenase-2 in human myometrial cells. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;181:359–366. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(99)70562-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matsumoto A, Deyama Y, Deyama A, Okitsu M, Yoshimura Y, Suzuki K. Epidermal growth factor receptor-mediated expression of NF-kappaB transcription factor in osteoblastic MC3T3-E1 cells cultured under a low-calcium environment. Life Sci. 1998;62:1623–1627. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(98)00118-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Biswas DK, Cruz AP, Gansberger E, Pardee AB. Epidermal growth factor-induced nuclear factor kappa B activation: a major pathway of cell-cycle progression in estrogen-receptor negative breast cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:8542–8547. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.15.8542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baeuerle PA. IkappaB-NF-kappaB structures: at the interface of inflammation control. Cell. 1998;95:729–731. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81694-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roff M, Thompson J, Rodriguez MS, Jacque JM, Baleux F, Arenzana-Seisdedos F, Hay RT. Role of IkappaBalpha ubiquitination in signal-induced activation of NFkappaB in vivo. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:7844–7850. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.13.7844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kniss DA, Rovin B, Fertel RH, Zimmerman PD. Blockade NF-kappaB activation prohibits TNF-alpha-induced cyclooxygenase-2 gene expression in ED27 trophoblast-like cells. Placenta. 2001;22:80–89. doi: 10.1053/plac.2000.0591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Allport VC, Slater DM, Newton R, Bennett PR. NF-kappaB and AP-1 are required for cyclo-oxygenase 2 gene expression in amnion epithelial cell line (WISH) Mol Hum Reprod. 2000;6:561–565. doi: 10.1093/molehr/6.6.561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Garat C, Arend WP. Intracellular IL-1Ra type 1 inhibits IL-1-induced IL-6 and IL-8 production in Caco-2 intestinal epithelial cells through inhibition of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase and NF-kappaB pathways. Cytokine. 2003;23:31–40. doi: 10.1016/s1043-4666(03)00182-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Janelle ME, Gravel A, Gosselin J, Tremblay MJ, Flamand L. Activation of monocyte cyclooxygenase-2 gene expression by human herpesvirus 6. Role for cyclic AMP-responsive element-binding protein and activator protein-1 . J Biol Chem. 2002;277:30665–30674. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203041200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miller C, Zhang M, He Y, Zhao J, Pelletier JP, Martel-Pelletier J, Di Battista JA. Transcriptional induction of cyclooxygenase-2 gene by okadaic acid inhibition of phosphatase activity in human chondrocytes: co-stimulation of AP-1 and CRE nuclear binding proteins. J Cell Biochem. 1998;69:392–413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leaman DW, Pisharody S, Flickinger TW, Commane MA, Schlessinger J, Kerr IM, Levy DE, Stark GR. Roles of JAKs in activation of STATs and stimulation of c-fos gene expression by epidermal growth factor. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:369–375. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.1.369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cano E, Mahadevan LC. Parallel signal processing among mammalian MAPKs. Trends Biochem Sci. 1995;20:117–122. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)88978-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zakar T, Mijovic JE, Eyster KM, Bhardwaj D, Olson DM. Regulation of prostaglandin H2 synthase-2 expression in primary human amnion cells by tyrosine kinase dependent mechanisms. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1391:37–51. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2760(97)00195-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ganster RW, Taylor BS, Shao L, Geller DA. Complex regulation of human inducible nitric oxide synthase gene transcription by Stat 1 and NF-kappa B. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:8638–8643. doi: 10.1073/pnas.151239498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yu Z, Zhang W, Kone BC. Signal transducers and activators of transcription 3 (STAT3) inhibits transcription of the inducible nitric oxide synthase gene by interacting with nuclear factor kappaB. Biochem J. 2002;367:97–105. doi: 10.1042/BJ20020588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Meydan N, Grunberger T, Dadi H, Shahar M, Arpaia E, Lapidot Z, Leeder JS, Freedman M, Cohen A, Gazit A, Levitzki A, Roifman CM. Inhibition of acute lymphoblastic leukaemia by a Jak-2 inhibitor. Nature. 1996;379:645–648. doi: 10.1038/379645a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Singh RP, Dhawan P, Golden C, Kapoor GS, Mehta KD. One-way cross-talk between p38(MAPK) and p42/44(MAPK). Inhibition of p38(MAPK) induces low density lipoprotein receptor expression through activation of the p42/44(MAPK) cascade. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:19593–19600. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.28.19593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bennett BL, Sasaki DT, Murray BW, O’Leary EC, Sakata ST, Xu W, Leisten JC, Motiwala A, Pierce S, Satoh Y, Bhagwat SS, Manning AM, Anderson DW. SP600125, an anthrapyrazolone inhibitor of Jun N-terminal kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:13681–13686. doi: 10.1073/pnas.251194298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alessi DR, Cuenda A, Cohen P, Dudley DT, Saltiel AR. PD 098059 is a specific inhibitor of the activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase in vitro and in vivo. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:27489–27494. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.46.27489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huang ZF, Massey JB, Via DP. Differential regulation of cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) mRNA stability by interleukin-1 beta (IL-1 beta) and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-alpha) in human in vitro differentiated macrophages. Biochem Pharmacol. 2000;59:187–194. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(99)00312-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang Z, Tai HH. Interleukin-1 beta and dexamethasone regulate gene expression of prostaglandin H synthase-2 via the NF-kB pathway in human amnion derived WISH cells. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 1998;59:63–69. doi: 10.1016/s0952-3278(98)90053-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Takanami-Ohnishi Y, Asada S, Tsunoda H, Fukamizu A, Goto K, Yoshikawa H, Kubo T, Sudo T, Kimura S, Kasuya Y. Possible involvement of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase in decidual function in parturition. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;288:1155–1161. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kumar A, Middleton A, Chambers TC, Mehta KD. Differential roles of extracellular signal-regulated kinase-1/2 and p38(MAPK) in interleukin-1beta- and tumor necrosis factor-alpha-induced low density lipoprotein receptor expression in HepG2 cells. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:15742–15748. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.25.15742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ono K, Han J. The p38 signal transduction pathway: activation and function. Cell Signal. 2000;12:1–13. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(99)00071-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hansen WR, Marvin KW, Potter S, Mitchell MD. Tumour necrosis factor-alpha regulation of prostaglandin H synthase-2 transcription is not through nuclear factor-kappaB in amnion-derived AV-3 cells. Placenta. 2000;21:789–798. doi: 10.1053/plac.2000.0576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ridley SH, Dean JL, Sarsfield SJ, Brook M, Clark AR, Saklatvala J. A p38 MAP kinase inhibitor regulates stability of interleukin-1-induced cyclooxygenase-2 mRNA. FEBS Lett. 1998;439:75–80. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)01342-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yoo JY, Wang W, Desiderio S, Nathans D. Synergistic activity of STAT3 and c-Jun at a specific array of DNA elements in the alpha 2-macroglobulin promoter. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:26421–26429. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009935200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wan YS, Wang ZQ, Voorhees J, Fisher G. EGF receptor crosstalks with cytokine receptors leading to the activation of c-Jun kinase in response to UV irradiation in human keratinocytes. Cell Signal. 2001;13:139–144. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(00)00146-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]