Abstract

Although child abduction is a low-rate event, it presents a serious threat to the safety of children. The victims of child abduction face the threat of physical and emotional injury, sexual abuse, and death. Previous research has shown that behavioral skills training (BST) is effective in teaching children abduction-prevention skills, although not all children learn the skills. This study compared BST only to BST with an added in situ training component to teach abduction-prevention skills in a small-group format to schoolchildren. Results showed that both programs were effective in teaching abduction-prevention skills. In addition, the scores for the group that received in situ training were significantly higher than scores for the group that received BST alone at the 3-month follow-up assessment.

Keywords: behavioral skills training, children, abduction prevention, in situ training

The abduction of a child is a low-probability event with potentially disastrous consequences. When a child is abducted by a nonfamily member, the consequences may involve sexual abuse and even death. In some cases the child is kept permanently (Finkelhor, Hammer, & Sedlak, 2002). According to the U.S. Department of Justice, there are two types of abduction committed by someone other than a family member: nonfamily abduction and stereotypical kidnappings. Finkelhor et al. define nonfamily abduction as

an abduction perpetrated by a stranger or slight acquaintance involving the movement of a child using physical force or threat, the detention for a substantial period of time (at least 1 hour) in a place of isolation using threat or physical force, or the luring of a child younger than 15 years old for purposes of ransom, concealment, or intent to keep permanently. (p. 2)

Stereotypical kidnapping, a more serious form of abduction, is an “abduction perpetrated by a stranger or slight acquaintance in which a child is taken or detained overnight, transported a distance of 50 or more miles, held for ransom or with intent to keep the child permanently, or killed” (p. 2).

It is estimated that more than 50,000 nonfamily abductions and 100 stereotypical kidnappings occur each year. Forty percent of the victims of stereotypical kidnappings are killed, and another 4% are not recovered. Nearly half of all child victims in stereotypical kidnappings and nonfamily abductions are sexually abused (Finkehor et al., 2002). In addition, an estimated 19% of victims of stereotypical kidnappings are 5 years old and younger.

In response to this serious child-safety threat, a few safety skills training programs have been developed to teach children what to do if a stranger asks the child to leave with him or her. A handful of studies on abduction-prevention skills training has demonstrated that children are able to learn the safety skills and use these skills in simulated abduction situations when presented with an abduction lure. Poche, Brouwer, and Swearingen (1981) were the first to find that behavioral skills training (BST) was effective in teaching abduction-prevention skills to children. The authors developed and evaluated a BST program to teach 3 preschool children self-protective behaviors to prevent abduction. Training and in situ assessments took place on the school premises. Children were taught to respond to simple, authority, and incentive lures by saying “No, I have to go ask my teacher,” moving away within 3 s of the lure, and running towards the school building. In situ assessments were implemented to see if children could perform the correct safety responses when presented with a realistic abduction situation without the knowledge that they were being assessed. The results showed that after 1 week of training, all children were able to display the correct target behaviors to the three lures and that the skills were maintained for 1 of the 2 children available for assessment at the 3-month follow-up. Marchand-Martella, Huber, Martella, and Wood (1996) found similar results showing that BST was effective in teaching abduction-prevention skills but that the skills were not maintained over time.

Subsequent studies that have investigated the effectiveness of BST have evaluated group training procedures and have shown that, although most children learn the safety skills, some percentage of children do not (Carroll-Rowan & Miltenberger, 1994; Olsen-Woods, Miltenberger, & Foreman, 1998; Poche, Yoder, & Miltenberger, 1988). Poche et al. compared the effectiveness of BST with video modeling to video modeling alone and found that the BST children performed better than the children in the video modeling group. Carroll-Rowan and Miltenberger compared the effectiveness of classroom-based BST procedures with and without video modeling. Both training groups performed better than control children. Olsen-Woods et al. evaluated the effectiveness of added correspondence training to a BST program and found that BST procedures with and without correspondence training were effective in teaching abduction-prevention skills. In all three of these studies, however, even though the BST groups performed significantly better than the control groups, not all children learned the skills.

Using group training to teach abduction-prevention skills is a more efficient way for teachers to train a larger number of children. However, these studies demonstrate that there is a need to make BST more effective in group training (Miltenberger & Olsen, 1996). Research in firearm injury prevention has demonstrated that in situ training, in conjunction with BST, can increase the efficacy of training.

Himle, Miltenberger, Flessner, and Gatheridge (2004) evaluated BST and in situ training to teach 8 preschool children what to do if they should ever encounter a firearm. A multiple baseline design was used to evaluate BST for teaching children to not touch the firearm, leave the area, and tell an adult. Three of the 8 children performed the skills to criterion during in situ assessments. An in situ training phase was then implemented for the 5 children who failed to perform the skills. During in situ training, the child's trainer entered the situation and turned the assessment into a training session. The child then practiced the correct behavior a number of times with praise and feedback. Results indicated that these 5 children engaged in the correct behavior in follow-up in situ assessments. Similar findings were reported by Gatheridge et al. (2004) and Miltenberger et al. (2004). The results of these studies demonstrate that in situ training is an effective method for teaching children who do not learn the skills in the initial training phase, thereby increasing the overall effectiveness of group training.

Recently, Johnson et al. (2005) found that BST combined with in situ training was effective for teaching abduction-prevention skills to young children. In this study, Johnson et al. incorporated in situ training into BST from the beginning of training and showed that all children learned the skills. These results suggest that the effectiveness of BST may be enhanced with the inclusion of in situ training.

The purpose of this study was to compare the effectiveness of BST with in situ training, which involved repeated rehearsal of the skills in the natural environment, to BST without in situ training in teaching abduction-prevention skills in a small-group format to schoolchildren. Prior research has shown that adding in situ training to BST can increase its effectiveness, but research has not directly compared BST with and without in situ training. The following predictions were made: (a) Both the BST group and the in situ training group will score significantly higher than the control group on the in situ assessment at posttest; (b) the in situ training group will perform significantly better than the BST group on in situ assessments at posttest, 1-week, 1-month, and 3-month follow-ups; and (c) there will be a significant increase in performance for the in situ training group over time due to repeated rehearsals of the safety skills during in situ training.

Method

Participants

Fifty 6- and 7-year-old children were recruited from area afterschool programs. One child moved before training was completed, and 3 children in the in situ training group terminated participation in the study following training. Characteristics of the participants are provided in Table 1. A detailed description of the study was mailed home with the children. Parents who expressed an interest in the study were contacted. Only children whose parent or guardian signed the consent form participated in the study. The study was approved by the university institutional review board and the participating agencies.

Table 1. Demographic Characteristics of the Participants in Each Group Who Completed the Study.

| Control | BST | In situ | |

| Boys | 9 | 7 | 6 |

| Girls | 8 | 8 | 8 |

| Mean age | 7.12 | 7.18 | 6.74 |

| Age rangea | (6-4 to 7-8) | (6-3 to 7-7) | (6-0 to 7-4) |

| Grade | 1st and 2nd | 1st and 2nd | K through 2nd |

Years-months.

Setting

Training and assessments were conducted in a variety of novel locations (e.g., classroom, hallway) in three afterschool programs. The afterschool programs, housed in two local YMCA buildings and an elementary school building, provided recreational activities for children in kindergarten through sixth grade from 3:00 p.m. to 6:00 p.m. on school days. Children from a number of elementary schools participated at each site.

Experimental Design

The design was a mixed design. The between-subjects variable was the training group: BST, BST with in situ training, and control. Time was the within-subject variable; assessments were conducted at posttest, 1-week, 1-month, and 3-month follow-ups. A separate analysis was conducted at posttest with the control group because the control group was not assessed at follow-up.

Target Behaviors

The abduction-prevention skills consisted of three safety responses: saying “no” when presented with an abduction lure, immediately walking or running away from the confederate (the child must distance him- or herself at least 6 m from the abductor), and immediately telling an adult about the abduction lure.

The safety responses were coded with the following numerical values: 0 = agrees to leave with the abductor; 1 = does not agree to leave with the abductor but fails to say “no,” get away, or tell; 2 = says “no” but does not leave the area or tell an adult; 3 = says “no” and leaves the area but does not tell an adult; 4 = says “no,” leaves the area, and tells an adult.

Assessment

Abduction-prevention skills were assessed using in situ assessments, which took place at the child's afterschool program. A confederate, unknown to the child, conducted the in situ assessment. The gender of the confederates conducting these assessments was equated across all groups. Confederates were men and women in their early 20 s. In situ assessments took place within 1 week of training, and follow-up assessments were conducted 1 week later and again after 1 month and 3 months.

A confederate approached the child when the child had been left alone at a predetermined time and place and presented the child with one of the four abduction lures (randomly chosen for each child). The lures were similar to, but not identical to, those used in training. The child was not told that an assessment was taking place. In addition to the confederate, an assessor (unseen by the child) was present at each assessment to record the child's responses to the lure. If the child agreed to leave with the confederate, the confederate made up an excuse to terminate the interaction and leave without the child. If the child did not run away within 10 s, the confederate walked away. If the child engaged in the correct safety skills and told a teacher, the teacher thanked the child for reporting the incident.

Interobserver Agreement

The primary observer was the confederate involved in the assessments. The child's verbal response (e.g., says “no”) was tape-recorded by the confederate during each assessment. A second observer observed from a distance and recorded whether the child ran away. The parent or teacher recorded whether the child reported the incident. Agreement was calculated by dividing the number of agreements by the number of agreements plus disagreements for each of the four targeted responses (did not go with the abductor, said “no,” got away, told the adult). The figure was then multiplied by 100%. An agreement was defined as the two observers recording the same response. Overall, agreement was 100%.

Procedure

Each child was randomly assigned to one of three conditions: BST, in situ training, or control group. Training for the BST and in situ training groups was conducted in groups of 2 to 5 children over a 3-day period. Two graduate student researchers (women or men in their early 20 s) implemented the training program at each session. If a child missed a training session, an individual training session was implemented so that the child did not fall behind the group.

BST

The BST program involved instructions, modeling, rehearsal, praise, and corrective feedback to teach children skills to use if they were presented with an abduction lure. The target safety responses included saying “no,” running away, and telling an adult when presented with an abduction lure. Children were trained to respond safely to four commonly used abduction lures: simple, authority, incentive, and assistance. An example of the simple lure was, “Would you like to go for a walk?” An example the authority lure was, “Your mother told me to pick you up from school.” An example of the incentive lure was, “I have some candy in my car. Would you like to come with me to get some?” Finally, an example of an assistance lure was, “I lost my puppy. Would you like to help me look for it?”

In the first training session, the trainer discussed the types of lures used by an abductor. Next, the researchers explained the importance of being safe around strangers and described the three safety responses (say “no,” run away, and tell an adult). Children then verbally rehearsed these responses. Once each child could state the safety skills, the two trainers modeled the appropriate responses in the context of one of the four different abduction lures. After the child observed the safety skills modeled in response to the lure, the child rehearsed the safety skills in a variety of role-playing scenarios. During these scenarios, praise was provided for correct responses, and further instruction was given to correct errors. The child rehearsed the skills until they were demonstrated correctly without prompts in response to the lure.

The group was trained with two of the four lures in the first session and the remaining two lures in the second session. In the third session, training occurred with all four lures. The order of presentation of each lure across BST sessions was randomly determined.

BST with in Situ Training

BST was implemented in the same format as described above except that immediately following the third BST session an in situ training session occurred. The trainer left the child alone and observed surreptitiously from another location in the building. A confederate, unknown to the child, approached the child and presented the child with an abduction lure. After presentation of the lure, if the child demonstrated the correct safety responses, the trainer appeared and praised the child for the correct behavior. If the child failed to demonstrate the appropriate responses (say “no,” get away, and tell an adult), the trainer entered the situation and provided corrective feedback, modeling, and instructions until the child performed the appropriate safety responses. The child was required to perform the correct safety responses to the same lure over five consecutive rehearsals. In situ training was conducted after each subsequent assessment if the correct behaviors were not observed.

Control

Children in this group were assessed before receiving abduction-prevention skills training. Following participation in the assessment, children received one BST session to teach abduction-prevention skills.

Debriefing and Side-Effects Measurement

Following the completion of the study, the children were not told about the in situ assessments. This was done so that the children would not mistakenly assume that any future abduction lure was a test. The parents were encouraged to contact the researchers if they had any questions about their child's participation in the study. A parent evaluation questionnaire was sent to each child's home following completion of the study to determine any negative emotional or behavioral side effects and parental attitudes toward the program.

Results

Three children dropped out following the initial in situ assessment (1 boy from the BST group and 1 boy and 1 girl from the in situ training group) and 1 child terminated participation following the 1-week in situ assessment (1 boy from the in situ training group). Their data were not included in the analyses. We were unable to obtain 1-week in situ assessments for 2 children.

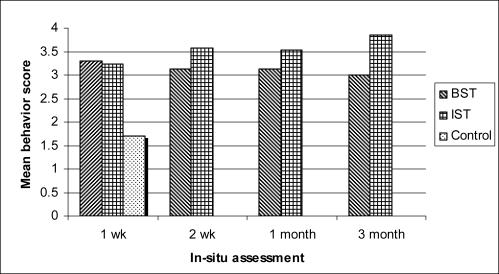

Although this study used an ordinal measure, the data were treated as interval data and were submitted to a mixed analysis of variance (ANOVA) to examine the interaction between treatment group and time of assessment. Nonparametric analyses, typically used with ordinal data, cannot be used to examine interactions directly. The ANOVA is robust to violations of the assumption that the data are interval or ratio (Gravetter & Wallnau, 2000). Nonetheless, the data were analyzed using nonparametric statistics as well (a Kruskal-Wallis test was conducted at posttest, 1-week, 1-month, and 3-month follow-ups for each of the two training groups). Overall, the parametric and nonparametric analyses yielded the same pattern of results. The mean scores for each condition (BST, in situ training, and control) on each of the in situ assessments are plotted in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Mean behavior scores for BST, in situ training, and control groups at posttest and mean scores for BST and in situ training at 1-week, 1-month, and 3-month in situ assessments.

A 2 × 4 mixed ANOVA was conducted, with treatment group (BST and in situ training) as the between-subjects variable and time (posttest, 1 week, 1 month, 3 months) as the within-subject variable. The Greenhouse-Geisser test was used to correct for violations of sphericity. A significant main effect was found for group, F(1, 20) = 4.458, p = .048. However, there was no significant main effect found for time and no significant interaction between group and time, suggesting that the effects of BST and in situ training did not change differentially over time.

Because a significant main effect was found for group, additional group comparisons were conducted for the posttest, 1-week, 1-month, and 3-month follow-ups. Scores for BST and in situ training groups were not significantly different from one another at posttest, 1 week, or 1 month. However, at the 3-month follow-up, the in situ training group (M = 3.85, SD = 0.376) scored significantly higher than the BST group (M = 3.0, SD = 1.0), t(24) = 2.65, p = .021. Although the in situ training group's performance improved from posttest to follow-up and the BST group's performance decreased slightly over time from posttest to follow-up, neither of these changes in performance over time was significant.

Participants from the control condition were tested only at posttest because we did not expect their scores to change over time without receiving training. We conducted an independent samples t test to test whether the BST and in situ training groups performed significantly better than the control group at posttest. Because no differences were found between in situ training and BST training at posttest in the analyses describe above, the data from the two training groups were combined when compared to the control group. Results showed that children in the training groups performed significantly better at posttest than did children in the control group, t(42) = 4.396, p = .000, two tailed.

Neither the BST nor the in situ training group obtained a mean score of 4 at the 1-week, 1-month, or 3-month follow-ups. In the BST group, 53% of the participants scored a 4 on the 1-week and 1-month follow-up and 45% of the participants scored a 4 at the 3-month follow-up. For the in situ training group, 71% of the participants scored a 4 at the 1-week follow-up, 69% did so at the 1-month follow-up, and 85% did so at the 3-month follow-up. None of the participants in either training group scored a 0 or 1 at the 1-week, 1-month, or 3-month follow-ups. However, 40% of the participants in the BST group scored a 2 (said “no” but did not run away or tell an adult) at the 1-week and 1-month follow-ups, and 45% scored a 2 at the 3-month follow-up. In contrast, only 14% and 15% of the participants in the in situ training group scored a 2 at the 1-week and 1-month follow-ups, respectively, and 0% scored a 2 at the 3-month follow-up (see Table 2 for percentages).

Table 2. Percentage of Participants Who Obtained Each Behavior Score at Each Follow-Up Assessment.

| Time | Group | Behavior scores |

||||

| 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 | ||

| Posttest | IST | 62 | 15 | 15 | 0 | 8 |

| BST | 57 | 14 | 29 | 0 | 0 | |

| C | 12 | 6 | 47 | 12 | 23 | |

| 1 week | IST | 71 | 14 | 14 | 0 | 0 |

| BST | 53 | 7 | 40 | 0 | 0 | |

| 1 month | IST | 69 | 15 | 15 | 0 | 0 |

| BST | 53 | 7 | 40 | 0 | 0 | |

| 3 months | IST | 85 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| BST | 45 | 9 | 45 | 0 | 0 | |

Note. IST = in situ training group, BST = behavioral skills training group, C = control group.

We conducted an ANOVA to determine whether there were any differences between boys and girls or between 6- and 7-year-olds in safety skills for each group at each assessment. The results showed no significant differences.

Side-Effects Questionnaire

Forty-five questionnaires were mailed to the parents or guardians of children who completed training. Eleven questionnaires were completed and returned to the researchers (see Table 3 for the questions and the results). All but one of the parents were pleased or very pleased that their children participated in the study. Half of the parents reported an increase in confidence in their children after participating in the study. Most parents reported that their children were more aware of their surroundings following training. Only 1 child was reported to be more scared, cautious, or upset following training. When asked to describe the changes in their children's behavior, one parent indicated that his or her child “seemed more knowledgeable,” one parent reported that his or her child “talks about what not to do,” one parent reported that his or her child was “confident” and “proud” that she knew what to do, and one parent reported that his or her child “looks at people more closely.” One of the 11 parents who completed the questionnaire had terminated his or her child's participation in the study.

Table 3. Questions and Responses on the Side-Effects Questionnaire.

| 1. How pleased are you that your child participated in the study? |

| very pleased – 7; pleased – 3; neutral – 1 |

| 2. Compared to before the study my child appears: |

| a) Confident: more self-reliant, more trustful |

| much more confident – 2; a little more confident – 3; no change – 5 |

| b) Aware of their surroundings |

| much more aware – 3; a little more aware – 5; no change – 3 |

| c) Scared: for example, afraid to leave parents, showing fear of strangers, etc. |

| less scared – 1; no change – 9; much more scared – 1 |

| d) Cautious: more hesitant to go outside or be alone |

| no change – 10; much more cautious – 1 |

| e) Upset: preoccupied with the issue of strangers, personal safety, etc. |

| no change – 10; much more upset - 1 |

Discussion

The study's first hypothesis, that both BST and in situ training groups would perform better than the control group at posttest, was supported. However, our second hypothesis, that the in situ training group would perform better than the BST group at posttest and at all follow-up assessments, was not supported. Instead the only significant difference between in situ training and BST was at the 3-month follow-up assessment. Finally, our third hypothesis was not supported. Although we saw an increase in in situ training group performance and a decrease in BST group performance over time, the changes were not significant.

This study was the first to directly compare BST and in situ training in teaching safety skills to schoolchildren. These findings demonstrate that BST with in situ training initially was not more effective than BST alone in teaching abduction-prevention skills in a small-group format to schoolchildren, but that by the 3-month follow-up, it was more effective. These results show that in situ training and BST produced immediate effects that were similar but that in situ training produced significantly greater performance of safety skills than did BST at 3 months. Although both BST and in situ training groups performed better than the control group, only 3 children in the control group scored a 0 in the in situ assessment. This finding suggests that by the age of 6 or 7, children may already have learned not to leave with strangers.

One limitation of this study is that the in situ training group received more training than did the BST group. Although initial training time and number of rehearsals were equal for both groups prior to the posttest assessment, the participants in the in situ training group received an in situ training session following posttest, 1-week, and 1-month assessments, whereas the BST participants did not receive any further training. Therefore the difference in in situ training and BST scores at the 3-month assessment cannot be unequivocally attributed to the in situ training. It is possible that additional BST sessions may have produced the same effect. However, previous studies indicate that in situ training produces skill acquisition, whereas additional BST sessions do not lead to skill acquisition following the failure of initial BST sessions (Himle, Miltenberger, Flessner, & Gatheridge, 2004; Miltenberger et al., 2004).

It is not clear what behavioral mechanism accounted for the superiority of in situ training over BST at the 3-month follow-up. One possibility is the repeated practice of the skills with feedback by the in situ training group. Another is the development of stimulus control as a result of training in the assessment situation. Finally, it is possible that “getting caught” not performing the skills as instructed may have functioned as an aversive stimulus (an establishing operation), and the execution of the skills in the next assessment was negatively reinforced by avoidance of getting caught again. Future research needs to examine the factors that contribute to the effectiveness of in situ training.

Another limitation of this study is that 4 children terminated participation in the study. Researchers terminated the participation of 2 children who cried during the initial in situ assessment after the confederate presented the lure. The parents of a 3rd child who terminated after the initial assessment and a 4th child who terminated following the 1-week assessment contacted researchers and asked that their children be dropped from the study. Both parents reported that their children did not want to be left alone because they were afraid that strangers might approach them. This presents a dilemma because the data suggest that additional in situ training enhanced performance, but 3 children demonstrated discomfort or fear as a result of the training procedures. Future research should investigate ways to promote generalization of the skills without repeated exposures to in situ assessment and training sessions. Perhaps more salient consequences for correct performance (e.g., enthusiastic praise or other reinforcers) during training or in situ assessments would enhance generalization. Alternatively, attempts to create an establishing operation for correct performance may enhance generalization. Creating an establishing operation for correct performance might be accomplished during training through the use of video scenarios in which children respond incorrectly to abduction lures and get caught (i.e., receive in situ training). In this fashion, children could witness in situ training without experiencing repeated in situ assessments themselves.

We also did not conduct repeated assessments of the control group to evaluate whether changes in safety skills occurred over time without any intervention. In addition, we were unable to assess children outside the afterschool program or assess generalization of skills at home or other locations. Therefore, it is unknown whether abduction-prevention skills would generalize beyond the school setting. Future studies should assess generalization of abduction-prevention skills in a variety of settings.

A final limitation is the small number of side-effects questionnaires returned. Only 11 of the 45 questionnaires (24%) were returned. All but one parent who returned the questionnaire indicated that they were pleased with their child's participation. Furthermore, one parent reported an increase in fear in their child following the study, and eight parents indicated that their children were more aware of their surroundings following the study. Evidence of adverse side effects following abduction-prevention training has not been found in past studies that have administered a parental questionnaire (Miltenberger & Olsen, 1996). These results suggest that repeated exposure to abduction lures may have an adverse effect on some children.

The results of this study have several implications for abduction-prevention skills training in this population. One implication is that children may need a number of in situ training sessions to obtain the safety skills needed to resist an abduction lure. However, the practicality of using in situ training in the classroom is an obstacle, because it is an intensive procedure that requires time and effort on the part of the teachers. Future research will need to address this issue and attempt to make abduction-prevention training more efficient so that it is more likely to be widely adopted.

Past research in safety skills training programs has suggested that age may have an impact on the ability to learn these skills. Himle, Miltenberger, Gatheridge, and Flessner (2004) evaluated BST in teaching preschool children firearm safety skills and showed that preschoolers receiving BST were unable to perform the correct safety skills in the in situ assessment. In contrast, Gatheridge et al. (2004) demonstrated that BST was effective in teaching firearm safety skills to 6- and 7-year-olds and that in situ training enhanced its effectiveness. Although in situ training enhanced the effectiveness of BST in the Gatheridge et al. study, it did not immediately enhance the effectiveness of BST in the current study. Instead, the effect was seen only at the 3-month follow-up assessment after the children had received three in situ training sessions. One reason that in situ training worked more quickly with firearm-injury-prevention skills may be that the lures used in abduction-prevention skills training and firearm skills training present different consequences. In abduction-prevention skills training, the threat of a stranger is presented to the child only briefly. Once the lure is presented, the confederate walks away after 10 s even if the child doesn't exhibit the safety skills. The child may no longer feel an immediate threat and, for some children, the need to run away and tell is no longer pertinent. In contrast, in firearm skills training, once the child finds the firearm, the threat remains until the child gets away from the firearm and tells an adult. This difference in the presentation of threat might explain why our findings did not replicate those found in previous research on firearm injury prevention.

Although we instructed the confederate to walk away if the child said “no” or did not respond within 10 s because we defined a correct response as running away within 10 s of the lure, it is possible that the child learned that the confederate would leave eventually if he or she said “no” or did nothing. In future research, the confederate should be instructed to remain longer after presenting a lure so that the child's inappropriate behavior is not inadvertently reinforced.

Only a handful of studies has investigated group training of abduction-prevention skills (Carroll-Rowan & Miltenberger, 1994; Olsen-Woods et al., 1998; Poche et al., 1988). These studies have demonstrated that there is a need to make group BST more effective. The results of this study suggest that BST with in situ training was more effective than BST without in situ training in teaching abduction-prevention skills to schoolchildren, but that the increased effectiveness was not seen until in situ training was administered a number of times. These results suggest that children may need repeated exposure to training sessions in naturalistic settings to achieve the best results.

This study was the first to compare the effectiveness of BST only and BST with in situ training in teaching abduction-prevention skills to children. The findings suggest that both training procedures were effective in teaching abduction-prevention skills in a small-group format and that repeated exposure to in situ training sessions increased the effectiveness of BST. Nonetheless, not all of the children performed the safety skills during the in situ assessments. Future research should focus on how to make group training more effective and efficient so that all children learn the necessary skills to keep them safe from abduction.

Acknowledgments

This study was conducted as a Masters thesis by the first author.

References

- Carroll-Rowan L, Miltenberger R.G. A comparison of procedures for teaching abduction prevention to preschoolers. Education & Treatment of Children. 1994;17:113–129. [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Hammer H, Sedlak A.J. Nonfamily abducted children: National estimates and characteristics. 2002. Retrieved May 28, 2002, from http: ojjdp.ncjrs.org. [Google Scholar]

- Gatheridge B.J, Miltenberger R.G, Huneke D.G, Satterlund M.J, Mattern A.R, Johnson B.M, et al. A comparison of two programs to teach firearm injury prevention skills to 6 and 7 year old children. Pediatrics. 2004;114:e294–e299. doi: 10.1542/peds.2003-0635-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gravetter F, Wallnau L. Statistics for behavioral sciences (5th ed.) Belmont, CA: Wadsworth; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Himle M.B, Miltenberger R.G, Flessner C, Gatheridge B.J. Training and generalization of skills to prevent gun play in children. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2004;37:1–9. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2004.37-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Himle M.B, Miltenberger R.G, Gatheridge B.J, Flessner C. An evaluation of two procedures for training skills to prevent gun play in children. Pediatrics. 2004;113:70–77. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.1.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson B.M, Miltenberger R.G, Egemo-Helm K, Jostad C.M, Flessner C, Gatheridge B. Evaluation of behavioral skills training for teaching abduction prevention skills to young children. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2005;38:67–78. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2005.26-04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchand-Martella N, Huber G, Martella R, Wood S. Teaching preschoolers to avoid abduction by strangers: Evaluation of maintenance strategies. Education & Treatment of Children. 1996;19:55–59. [Google Scholar]

- Miltenberger R.G, Flessner C, Gatheridge B, Johnson B.M, Satterlund M.J, Egemo K.R. Evaluation of behavioral skills training procedures to prevent gun play in children. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2004;37:513–516. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2004.37-513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miltenberger R.G, Olsen L.A. Abduction prevention training: A review of findings and issues for future research. Education & Treatment of Children. 1996;19:69–82. [Google Scholar]

- Olsen-Woods L.A, Miltenberger R.G, Foreman G. Effects of correspondence training in an abduction prevention training program. Child & Family Behavior Therapy. 1998;20:15–34. [Google Scholar]

- Poche C, Brouwer R, Swearingen M. Teaching self-protection to young children. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1981;14:169–176. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1981.14-169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poche C, Yoder P, Mitenberger R. Teaching self-protection to children using television techniques. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1988;21:253–261. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1988.21-253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]