Abstract

Antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity, a key effector function for the clinical efficacy of monoclonal antibodies, is mediated primarily through a set of closely related Fcγ receptors with both activating and inhibitory activities. By using computational design algorithms and high-throughput screening, we have engineered a series of Fc variants with optimized Fcγ receptor affinity and specificity. The designed variants display >2 orders of magnitude enhancement of in vitro effector function, enable efficacy against cells expressing low levels of target antigen, and result in increased cytotoxicity in an in vivo preclinical model. Our engineered Fc regions offer a means for improving the next generation of therapeutic antibodies and have the potential to broaden the diversity of antigens that can be targeted for antibody-based tumor therapy.

Keywords: antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity, FcγR, protein engineering, cancer

Monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) have enormous potential as anticancer therapeutics, with inherent advantages such as specificity for target, low toxicity relative to small-molecule drugs, long half-life in serum, and the capacity for multiple cytotoxic mechanisms of action. There are eight approved anticancer antibody (Ab) products and numerous more in development. Despite such widespread use, however, the potency of Abs as anticancer agents remains suboptimal. Patient tumor response data show that even the most successful approved drugs provide incremental improvements in therapeutic success over single-agent chemotherapeutics. Many other promising Ab drugs, despite targeting antigens with favorable differential expression profiles, have failed in clinical trials because of insufficient demonstrable efficacy.

A promising means for enhancing the antitumor potency of Abs is through enhancement of their ability to mediate cellular cytotoxic effector functions such as Ab-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC) and Ab-dependent cell-mediated phagocytosis (ADCP) (1). For the IgG class of Abs, ADCC and ADCP are governed by engagement of the Fc region with a family of receptors referred to as the Fcγ receptors (FcγRs) (2). In humans, this protein family comprises FcγRI (CD64); FcγRII (CD32), including isoforms FcγRIIa, FcγRIIb, and FcγRIIc; and FcγRIII (CD16), including isoforms FcγRIIIa and FcγRIIIb (3, 4). FcγRs are expressed on a variety of immune cells, and formation of the Fc/FcγR complex recruits these cells to sites of bound antigen, typically resulting in signaling and subsequent immune responses such as release of inflammation mediators, B cell activation, endocytosis, phagocytosis, and cytotoxic attack. All FcγRs bind the same region on IgG Fc, yet with differing high (FcγRI) and low (FcγRII and FcγRIII) affinities (5, 6). Furthermore, whereas FcγRI, FcγRIIa/c, and FcγRIIIa are activating receptors characterized by an intracellular immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif (ITAM), FcγRIIb has an inhibition motif (ITIM) and is therefore inhibitory.

Three critical sets of data support the role of FcγR-mediated effector functions in Ab cancer therapy and the relationship between Fc/FcγR affinity and cytotoxic potency. First, xenograft studies in FcγR knockout mice indicate that activation receptors are necessary and inhibitory receptors detrimental to the efficacy of rituximab and trastuzumab (7). Second, a number of studies have documented a correlation between the clinical efficacy of Abs in humans and their allotype of high-affinity (V158) or low-affinity (F158) polymorphic forms of FcγRIIIa (8–10). Finally, it has been shown via mutagenesis (11–14) and glycoform engineering (15) that the affinity of interaction between Fc and certain FcγRs correlates with cytotoxicity in cell-based assays. Together these data suggest that an Ab with optimized FcγR affinity may be more cytotoxic against targeted cancer cells in patients (16). For this strategy, the balance between activating and inhibitory receptors is an important consideration, and optimal effector function may result from an Fc with enhanced affinity for activation receptors and reduced affinity for the inhibitory receptor FcγRIIb.

Attempts at improving Ab effector function through mutagenesis have met with incomplete success (14). We used a combination of computational structure-based protein design methods coupled with high-throughput protein screening to optimize the FcγR binding capacity of Abs. Here we present a series of engineered Fc variants with improved FcγR affinity and specificity that provide remarkable enhancements in cytotoxicity.

Results

Designed Fc Variants Have Optimized Binding Affinity for FcγRs.

A combination of “directed diversity” and “quality diversity” strategies were used to computationally optimize the IgG Fc region for FcγR affinity and specificity. Where structural information was available (e.g., the Fc/FcγRIII complex), we directly optimized affinity by designing substitutions that provide more favorable interactions at the Fc/FcγR interface. Where structural information was incomplete or lacking (e.g., the Fc/FcγRIIb complex), calculations provided a quality set of variants enriched for stability and solubility. The advantage of this capability is because of the innumerable amino acid modifications that are detrimental to proteins (17).

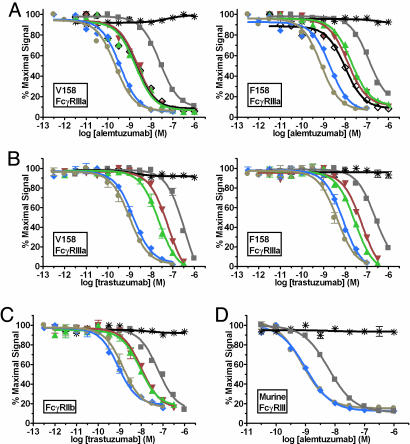

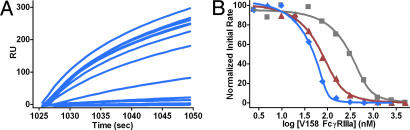

Variants were constructed in the context of the anti-CD52 Ab alemtuzumab, expressed and purified, and screened for FcγR affinity by using a semiautomated AlphaScreen assay. A number of engineered Fc variants show significant enhancements in binding affinity to human V158 FcγRIIIa and F158 FcγRIIIa (Fig. 1A). These variants include the single mutants S239D and I332E and the double and triple mutants S239D/I332E and S239D/I332E/A330L [Eu numbering (18)]. The variants show similar levels of enhancement in the context of the anti-Her2 Ab trastuzumab (Fig. 1B). Similar binding enhancements have been observed in the anti-CD20 Ab rituximab, the anti-EGFR Ab cetuximab, and all other Abs tested (data not shown). The fits to the binding data provide the inhibitory concentration 50% (IC50) for each Ab, enabling determination of the fold-improvements relative to WT (Table 1). Because of the high avidity nature of the assay, the AlphaScreen provides only relative affinities. True binding constants were obtained by using a competition surface plasmon resonance (SPR) experiment (19) in which unbound trastuzumab Ab in an Ab/FcγR equilibrium was captured to an FcγRIIIa surface. Initial binding rates were determined from sensorgram raw data (Fig. 2A), and KD values were calculated by plotting the log of receptor concentration against the initial rate obtained at each concentration (Fig. 2B and Table 1) (20). The WT KD (252 nM) agrees well with published data (208 nM from SPR; 535 nM from calorimetry) (21). KD values of the I332E (30 nM) and S239D/I332E (2 nM) variants indicate approximately one and two logs greater affinity to V158 FcγRIIIa, respectively.

Fig. 1.

Binding of Fc variant Abs to FcγRs measured by competition AlphaScreen. (A) Binding of alemtuzumab Fc variants to human V158 (Left) and F158 (Right) FcγRIIIa. (B) Binding of trastuzumab Fc variants to human V158 (Left) and F158 (Right) FcγRIIIa (n = 2). (C) Binding of trastuzumab Fc variants to human FcγRIIb (n = 2). (D) Binding of alemtuzumab variants to murine FcγRIII (n = 2). Black asterisk, buffer; gray squares, WT; black diamonds, S298A/E333A/K334A; green triangles, S239D; red inverted triangles, I332E; blue diamonds, S239D/I332E; and tan circles, S239D/I332E/A330L. The S298A/E333A/K334A variant was generated in a previous study (14) and is used here as comparison.

Table 1.

FcγR affinity enhancements of Fc variants

| Variant | Alem AS [LOG(IC50) (M)] fold |

Tras AS [LOG(IC50) (M)] fold |

Tras SPR [KD] fold |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| V158 IIIa | F158 IIIa | V158 IIIa | F158 IIIa | IIb | IIIa:IIb* | V158 IIIa | |

| WT | [−7.60 ± 0.02] 1 | [−6.90 ± 0.06] 1 | [−6.42 ± 0.06] 1 | [−6.61 ± 0.05] 1 | [−7.23 ± 0.07] 1 | 1 | [252 ± 89 nM] 1 |

| S298A/E333A/K334A† | [−8.71 ± 0.13] 13 | [−8.01 ± 0.10] 13 | |||||

| S239D | [−8.72 ± 0.12] 13 | [−7.72 ± 0.06] 7 | [−7.65 ± 0.06] 17 | [−7.55 ± 0.06] 9 | [−8.06 ± 0.07] 7 | 2 | |

| I332E | [−8.61 ± 0.08] 10 | [−7.89 ± 0.09] 10 | [−7.22 ± 0.05] 6 | [−7.23 ± 0.07] 4 | [−8.00 ± 0.06] 6 | 1 | [30 ± 7 nM] 8 |

| S239D/I332E | [−9.44 ± 0.08] 70 | [−8.70 ± 0.10] 63 | [−8.83 ± 0.05] 254 | [−8.10 ± 0.06] 31 | [−9.07 ± 0.05] 69 | 4 | [2 ± 2 nM] 126 |

| S239D/I332E/A330L | [−9.66 ± 0.07] 115 | [−9.12 ± 0.05] 169 | [−8.99 ± 0.05] 370 | [−8.38 ± 0.08] 58 | [−8.84 ± 0.07] 41 | 9 | |

Alemtuzumab (Alem) and trastuzumab (Tras) AlphaScreen (AS) or SPR data provide LOG(IC50) or KD [bracketed] values followed by folds relative to WT. Fold = IC50variant/IC50WT.

*IIIa:IIb = fold V158 FcγRIIIa/fold FcγRIIb for trastuzumab.

†Generated in a previous study (14) and used here for comparison.

Fig. 2.

Affinity of Fc variant trastuzumab Abs for V158 FcγRIIIa measured by competition SPR. (A) Sensorgrams showing binding to an FcγRIIIa surface by unbound S239D/I332E Ab in an Ab/FcγRIIIa equilibrium at increasing receptor concentrations. (B) Plot of normalized initial binding rate vs. log of receptor concentration. Derived KD values are presented in Table 1. Line colors are as follows: gray, WT; red, I332E; and blue, S239D/I332E.

Binding of the trastuzumab Fc variants to the inhibitory receptor FcγRIIb also was measured by the AlphaScreen (Fig. 1C). As discussed, optimal effector function may result from Fc variants that provide greater affinity to activating FcγRs relative to the inhibitory receptor FcγRIIb. We refer to this property as a variant’s IIIa:IIb profile, and define it quantitatively as the fold-FcγRIIIa affinity divided by the fold-FcγRIIb affinity (Table 1). Combination of the A330L mutation with S239D/I332E provides increased FcγRIIIa affinity and reduced FcγRIIb affinity relative to the double variant (Fig. 1 A–C and Table 1), resulting in a significant improvement in IIIa:IIb profile. Enhancements in affinity for the variants also were observed for binding to the human activating receptor FcγRI (data not shown).

Differences between human and mouse FcγRs complicate the use of mouse cancer models for evaluating the Fc variants in vivo. We investigated the capacity of the double and triple alemtuzumab variants to enhance affinity to the mouse activating receptor FcγRIII by using the AlphaScreen (Fig. 1D). The data show that the S239D/I332E and S239D/I332E/A330L variants also provide significant improvements in binding to this receptor.

Designed Fc Variants Mediate Enhanced ADCC.

Cell-based assays were performed to evaluate the capacity of the Fc variants to mediate ADCC. Purified human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) allotyped for the V/F158 FcγRIIIa polymorphism were used as effector cells, and lysis was measured by using europium (Eu)-based detection. Trastuzumab Fc variants were tested by using the Her2+ breast carcinoma cell line SkBr3 (Fig. 3A). The designed Fc variants provide substantial ADCC enhancements over WT, and the relative ADCC enhancements are proportional to their FcγRIIIa affinities. Between two and three logs improvement in potency are observed for all three allelic forms, reflected in shifts in EC50 (effective concentration 50%) toward lower concentrations. Additionally, shifts are observed toward higher maximal levels of ADCC at saturating concentrations, reflecting improvements in the relative efficacy of the variants. Substantial enhancements also are observed for the Fc variants in the context of alemtuzumab (Fig. 3B) and rituximab (Fig. 3C), using release of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) as the detection method. The variants provide comparable enhancements in all other Abs tested (data not shown), again consistent with the context-independence of the improvements.

Fig. 3.

Cell-based ADCC assays of Fc variant Abs. (A) Eu-based detection assays of trastuzumab Abs against SkBr3 breast carcinoma target cells in the presence of human PBMCs allotyped for V/V (Top), V/F (Middle), or F/F (Bottom) 158 FcγRIIIa. (B) LDH-based detection assay of alemtuzumab Abs against DoHH-2 lymphoma target cells in the presence of human PBMCs allotyped for F/F158 FcγRIIIa. (C) LDH-based detection assay of rituximab Abs against WIL2-S lymphoma target cells in the presence of human PBMCs allotyped for F/F158 FcγRIIIa. n = 2 for all assays. Gray squares, WT; black diamonds, S298A/E333A/K334A (14); green triangles, S239D; red inverted triangles, I332E; blue diamonds, S239D/I332E; and tan circles, S239D/I332E/A330L.

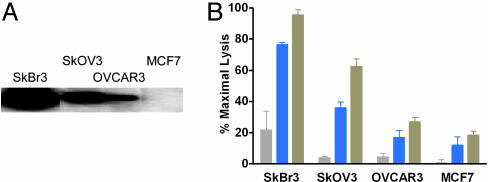

Designed Fc Variants Mediate Enhanced ADCC Across a Range of Antigen Expression Levels.

A critical parameter governing the clinical efficacy of anticancer Abs is the expression level of target antigen. Indeed, clinical trials of trastuzumab have been limited to patients showing a moderate (2+) to strong (3+) level of Her2 overexpression by immunohistochemistry (22), reflecting ≈500,000 and 2,300,000 receptors per cell respectively (23). To explore the cytotoxic capacity of our Fc variants at different antigen expression levels, ADCC was measured for WT and variant trastuzumab Abs against four different cell lines expressing amplified to low levels of Her2 (Fig. 4A). The S239D/I332E and S239D/I332E/A330L variants provide substantial ADCC enhancements over WT trastuzumab across a broad range of antigen expression level (Fig. 4B). In addition, at barely observable antigen expression and WT ADCC levels (the MCF7 cell line), ADCC using the variant Abs is improved above the detectable threshold.

Fig. 4.

Cell-based ADCC assay of trastuzumab Fc variants against cell lines expressing varying levels of Her2 receptor. (A) Western blot showing expression levels of Her2 for cell lines SkBr3 (≈106 copies per cell), SkOV3 (≈105 copies per cell), OVCAR3 (≈104 copies per cell), and MCF7 (≈102 to 103 copies per cell). Specified cancer cells were washed in PBS and resuspended at 1 × 105 cells per ml in lysis buffer. Equivalent amounts of each lysate were loaded per well of a SDS/PAGE gel, followed by Western analysis using 2 μg/ml commercial trastuzumab and 1 μg/ml horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary Ab. (B) ADCC of trastuzumab Fc variants against the Her2+ cell lines in the presence of human PBMCs (F/F158 FcγRIIIa). Ab concentration was 1 ng/ml, and lysis was measured by using Eu-based detection. Data were normalized to the minimum and maximum fluorescence signal provided PBMCs alone and Triton X-100, respectively (n = 3). Bar colors are as follows: gray, WT trastuzumab; blue, S239D/I332E; and tan, S239D/I332E/A330L.

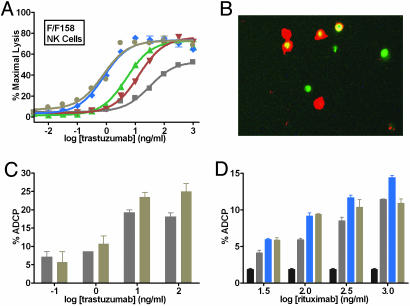

Enhanced Effector Function Is Mediated by Multiple Effector Cells.

To explore the specific cell types involved in target cell lysis, the roles of two PBMC components, natural killer (NK) cells and macrophages, were investigated. NK cells express only the activating receptors FcγRIIIa and in some cases FcγRIIc (24). Substantial cytotoxicity enhancements are observed by using NK cells as effector cells, including enhancements in both EC50 and in maximal lysis (Fig. 5A). Phagocytes such as macrophages, neutrophils, and dendritic cells express both activating and inhibitory FcγRs, and FcγR-mediated phagocytosis of target cells may result in acute cytotoxicity and promotion of adaptive immunity (25). Fluorescence imaging of differentially labeled macrophages and Her2+ target cells after coculture in the presence of S239D/I332E trastuzumab results in visible engulfment (Fig. 5B). Quantitative measurement of phagocytosis using flow cytometry indicates that the S239D/I332E/A330L variant provides a subtle yet significant enhancement in ADCP relative to WT trastuzumab at higher concentrations (Fig. 5C). A similar experiment in the context of rituximab shows ADCP enhancement for the S239D/I332E and S239D/I332E/A330L variants against CD20+ cells (Fig. 5D). The reason for the reduced ADCP of the triple variant at higher concentrations is unknown.

Fig. 5.

Role of NK cells and macrophages in mediating enhanced effector function. (A) Cell-based ADCC assay of variant trastuzumab Abs against SkBr3 breast carcinoma target cells in the presence of human F/F158 FcγRIIIa NK cells. Lysis was measured by using LDH-based detection. Gray squares, WT trastuzumab; green triangles, S239D; red inverted triangles, I332E; blue diamonds, S239D/I332E; and tan circles, S239D/I332E/A330L. (B) Dual fluorescence merge image of PKH67-labeled SkBr3 cells (green) and RPE-anti-CD11/anti-CD14-labeled macrophages (red) after a 24-h coculture (3:1 macrophage:SkBr3 ratio) in the presence of 100 ng/ml S239D/I332E. Phagocytosis of green target cells within red-labeled macrophages is detected as yellow in the merge image. (C) ADCP enhancement of Fc variant trastuzumab Ab against SkBr3 target cells, measured using flow cytometry. (D) ADCP enhancement of Fc variant rituximab Abs against WIL2-S target cells. % ADCP represents the number of colabeled cells (macrophage plus target) over the total number of target cells in the population (phagocytosed plus nonphagocytosed) after 10,000 counts. Bar colors are as follows: black, buffer; gray, WT trastuzumab; blue, S239D/I332E; and tan, S239D/I332E/A330L. (n = 2 for all assays.)

Designed Fc Variants Show Differential Capacity to Mediate Complement-Dependent Cytotoxicity (CDC).

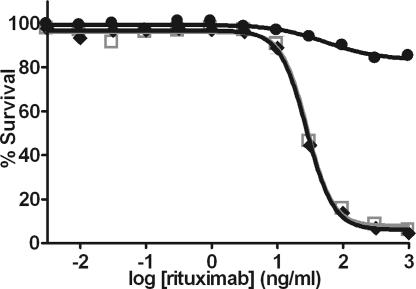

CDC is another effector function by which some Abs may destroy tumor cells. Interaction of Ab with complement is mediated by the protein C1q, the binding site for which is separate from but overlapping with the FcγR site (26, 27). Alamar Blue release was used to monitor lysis of Fc variant and WT rituximab-opsonized CD20+ target cells by human serum complement. Whereas S239D/I332E rituximab elicits CDC comparable with WT, the addition of A330L ablates CDC (Fig. 6). This result is not surprising given the proximity of A330 to the C1q binding site (26, 27). The set of S239D/I332E and S239D/I332E/A330L variants thus provide the option for enhancing ADCC in cases where CDC is desired or undesired. Notably, other substitutions at position 330 provide similar enhancements in FcγRIIIa affinity and IIIa:IIb profile yet do not affect CDC (data not shown).

Fig. 6.

Cell-based CDC assay of rituximab Fc variants. Lysis of WIL2-S lymphoma target cells in the presence of human complement was measured by using Alamar Blue release (n = 2). Gray squares, WT rituximab; black diamonds, S239D/I332E; and black circles, S239D/I332E/A330L.

Designed Fc Variants Mediate Enhanced B Cell Depletion in Macaques.

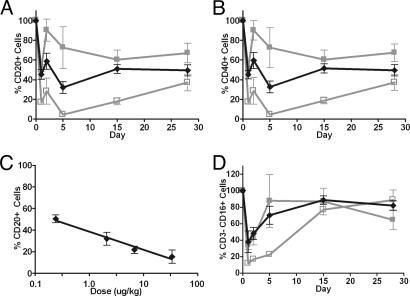

Peripheral B cell depletion by rituximab in cynomolgus monkeys has been reported as a suitable measure of anti-CD20 cytotoxicity (28). The advantage of this system is that monkey FcγRs, in contrast to those in mice, are highly homologous to human receptors. Four variant and two WT doses were evaluated to approximate the dose required to deplete 50% of circulating B cells. An enhanced level of B cell depletion is observed for the S239D/I332E variant relative to WT as measured by the population of CD20+ (Fig. 7A) and CD40+ (Fig. 7B) cells. Both variant and WT show a characteristic rebound in B cells (28) followed by further reduction and gradual recovery, with the greatest level of depletion occurring at day 5. B cell level was not yet fully recovered at 28 days but returned to predose levels by day 84 (data not shown). Interpolation of the day 5 data at the approximate dose required for 50% B cell depletion suggests a dose of nearly 10 μg/kg per day for WT, in good agreement with historical data (28). For the S239D/I332E variant, a dose of 0.2 μg/kg per day is sufficient for 50% depletion (Fig. 7C), an apparent ≈50-fold increase in potency. Concerns about the potential for Ab/FcγRIIIa interactions to promote apoptosis of activated NK cells (29) also led us to investigate the effect of the variant rituximab on NK cell levels. A dose-dependent decrease in NK cells is observed in all groups as measured by the population of CD3−/CD16+ (Fig. 7D) cells, correlated with the degree of B cell depletion effected. No difference is observed in the relative reduction of NK cells compared with B cells between WT and variant anti-CD20 Abs. NK cell populations recovered to predose range within 2 weeks of the initial dose. Identical NK cell results were obtained monitoring CD3−/CD8+ cells (data not shown). No significant changes were observed in monocytes, T helper lymphocytes, T cytotoxic/suppressor lymphocytes, or total T lymphocytes as measured by the populations of CD3−/CD14+, CD3+/CD4+, CD3+/CD8+, and CD3+ cells, respectively (data not shown).

Fig. 7.

B cell depletion in macaques. (A) Percent CD20+ B cells remaining during treatment with WT and S239D/I332E rituximab Abs. (B) Percent CD40+ B cells remaining during treatment. (C) Dose-response of CD20+ B cell levels to treatment with S239D/I332E rituximab, acquired at day 5. (D) Percent CD3−/CD16+ NK cells remaining during treatment. Data reported are group averages of three monkeys per treatment group (n = 3). Symbols and experimentally determined doses are as follows: filled gray squares, WT rituximab (2 μg/kg), open gray squares, WT rituximab (34 μg/kg); and black diamonds, S239D/I332E (2 μg/kg).

Discussion

We have capitalized on recent advances in protein engineering to generate a series of Fc variants with optimized FcγR affinity, enhanced effector function in cell-based assays, and increased efficacy in a preclinical animal system. Our method relies heavily on state-of-the-art computer algorithms to search sequence-structure space, semiautomated protein expression and purification, and a high-throughput primary screen that is extremely reliable at identifying variants with desirable properties.

There were several engineering challenges in this study, including the essentially identical binding sites on Fc for the activating and inhibitory receptors, the proximal but overlapping putative binding site for C1q, and the fact that homodimeric Fc binds asymmetrically to monomeric FcγR. A consequence of this latter issue is that a designed substitution is effectively two mutations, one on each side of the interface yet in distinct structural environments. Thus, substitutions that result in overall enhanced receptor affinity are those in which the sum of interactions at both interfaces is energetically beneficial. Detailed structural analysis of the mutations is provided in Supporting Text and Fig. 8, which are published as supporting information on the PNAS web site.

The variants with the greatest enhancements in FcγRIIIa affinity also significantly increase binding to FcγRIIb. The addition of A330L to S239D/I332E provides a moderate but significant improvement in IIIa:IIb profile. The simultaneous FcγRIIIa affinity improvement of the triple variant over the double and its subtle but questionable ADCC enhancement make it difficult to draw conclusions about the sufficiency of the improved specificity and related impact on in vitro effector function. The relevance of receptor selectivity is speculative, based primarily on improved antitumor efficacy in FcγRII-deficient mice (7). Theoretically the optimal variant with respect to human receptors is selective for FcγRIIa and FcγRIIc over FcγRIIb.

Affinity was improved for both the V158 and F158 forms of FcγRIIIa, and ADCC enhancements were observed using PBMCs from donors homozygous for both allelic forms of the receptor. The clinical relevance of the V/F158 polymorphism is well supported (8, 9), and given the predominance of F158 in the population (≈20% V/V, 40% V/F, and 40% F/F), affinity for this low-affinity/low-responder receptor is an important clinical parameter. Notably, affinities of the best variants for F158 FcγRIIIa are significantly better than that of WT for the V158 isoform, inferred from the AlphaScreen data. This result suggests that the variants may enable the clinical efficacy of Abs for the less-responsive patient population to achieve that currently possible for high responders (8–10). Together the results indicate that the Fc variants will be broadly applicable to the entire patient population and that clinical improvement will potentially be greatest for the less-responsive patients who need it most.

Results from the cell-based assays show that both NK cells and macrophages are active PBMC components in the enhanced effector function of the Fc variants. Although not well characterized, the relative importance of different cell types in Ab therapy is likely cancer-dependent, due to a minimum to differences in tumor location/accessibility and the particular immune state of a given patient. It follows that with regard to effector function it may be sensible to separate cancers into hematologic and solid tumors. The presence of NK cells in peripheral blood and their capacity for FcγRIIIa-mediated target cell lysis are logical bases of support for the importance of NK cells in rituximab-mediated lymphoma cytotoxicity. The role of other effector cells is supported by the enhanced rituximab protection in FcγRII−/− mice (7), in agreement with the FcγR-dependent role of macrophages observed in the ADCP assay of the present study. The contribution of ADCP to Ab therapy may be twofold. Engulfment can result in immediate destruction of target cells, akin to ADCC. Additionally, FcγR-mediated phagocytosis and endocytosis are mechanisms of antigen uptake, potentially leading to antigen presentation and adaptive immunity (25). FcγR- and Ab-mediated dendritic cell maturation, antigen presentation, and antitumor T cell immunity have been demonstrated in mice (30–32) and by human cells in vitro (33–35). Nonetheless, the role of adaptive immunity in mAb therapy remains unclear. In addition to their potential for improving clinical outcome, our Fc variants will be a unique set of reagents with which to investigate the relevance of different receptors, cell types, effector functions, and immune responses to Ab mechanism of action.

Our B cell depletion experiments deliberately focused on the macaque system to maintain a high degree of homology with human immune biology. The S239D/I332E variant clearly shows increased potency relative to WT rituximab, consistent with its enhanced receptor affinity and ADCC in vitro, and with the observation that B cell depletion by rituximab in vivo is dominated by FcγR-mediated mechanisms (36, 37). A number of factors may affect in vivo performance, including the high concentration of nonspecific IgG in serum (37, 38). The macaque experiment was undertaken because, short of a clinical trial, it is the best predictor of clinical effect. Accordingly, the capacity of the engineered Fc region to substantially enhance efficacy in the current model is significant motivation for its use in clinical trials.

Together the improvements in effector function, the enhancement for the more common yet less responsive F158 FcγRIIIa allele, and the greater killing capacity at lower antigen expression levels have promising implications for mAb therapy. Most evident is the possibility of expanding the population of patients responsive to treatment. An equally profound implication is the potential impact on the clinical utility of targets. The ability to target a given tumor antigen depends on an array of parameters including expression level, expression profile, structural and spatial organization in the membrane, requirement for growth or metastasis, and capacity to signal. These latter two factors have thus far been the most indicative of clinical response; all currently approved anticancer Abs perturb growth or signaling in some manner, either by blocking activation or accelerating turnover of a needed growth factor receptor or by eliciting apoptotic signaling events. Yet some antigens that show promising differential expression, for example mucins and adhesion proteins, may serve merely as “tumor handles” for the immune system. Overexpression of such proteins on tumors is perhaps related more to their role in metastasis or immune evasion rather than conferral of some proliferative advantage. Despite the number of approved Abs with the capacity to inhibit growth or signaling, it may not be a requisite for success. Rather, inability to directly affect growth may mean that an Ab must rely more heavily on mechanisms of action that involve engagement of the immune system, namely FcγR- and complement-mediated cytotoxicity. The improvements observed for the Fc variants described here are a significant step toward enabling the targeting of a broader and more diverse set of tumor antigens.

Materials and Methods

Protein Design.

Design calculations were carried out by using Protein Design Automation technology (39) and Sequence Prediction Algorithm technology (40). Detailed description is provided in Supporting Text.

Construction, Expression, and Purification of Ab Variants and FcγRs.

Variant Abs were constructed by using quick-change mutagenesis, expressed in 293T cells, and purified by using protein A chromatography. FcγRs were constructed as C-terminal −6xHis-GST fusions, expressed in 293T (human FcγRs) or NIH 3T3 (mouse FcγRIII) cells, and purified by using nickel affinity chromatography. Detailed description is provided in Supporting Text.

Binding Assays.

AlphaScreen assays used untagged Ab to compete the interaction between biotinylated IgG bound to streptavidin donor beads and FcγR-His-GST bound to anti-GST acceptor beads. Competition SPR (19) experiments measured capture of free Ab from a preequilibrated Ab/receptor analyte mixture to V158 FcγRIIIa-His-GST bound to an immobilized anti-GST surface. Equilibrium dissociation constants (KD values) were calculated by using the proportionality of initial binding rate on free Ab concentration in the Ab/receptor equilibrium (20). Detailed description of AlphaScreen and SPR assays is provided in Supporting Text.

Cell-Based Assays.

ADCC was measured by using either the DELFIA EuTDA-based cytotoxicity assay (PerkinElmer) or the LDH Cytotoxicity Detection Kit (Roche Diagnostics). Human PBMCs were purified from leukopacks by using a Ficoll gradient and allotyped for V/F158 FcγRIIIa by using PCR (41). NK cells were isolated from human PBMCs by using negative selection and magnetic beads (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA). Target cell lines were obtained from American Type Culture Collection. For Eu-based detection, target cells were first loaded with BATDA [Bis(acetoxymethyl)-2,2′:6′,2″-terpyridine-6,6″-dicarboxylate] at 1 × 106 cells per ml and washed 4×. For both Eu- and LDH-based detection, target cells were seeded into 96-well plates at 10,000 cells per well, and opsonized by using Fc variant or WT Abs at the indicated final concentration. Triton X-100 and PBMCs alone were run as controls. Effector cells were added at 25:1 PBMCs:target cells or 4:1 NK cells:target cells, and the plate was incubated at 37°C for 4 h. Cells were incubated with either Eu3+ solution or LDH reaction mixture, and fluorescence was measured by using a Fusion Alpha-FP (PerkinElmer). Data were normalized to maximal (Triton) and minimal (PBMCs alone) lysis and fit to a sigmoidal dose-response model.

For phagocytosis experiments, monocytes were isolated from human V/F158 FcγRIIIa PBMCs by using a Percoll gradient and differentiated into macrophages by culture with 0.1 ng/ml granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor for 1 week. For imaging, SkBr3 target cells were labeled with PKH67 (Sigma) and cocultured for 24 h with macrophages at a 3:1 effector:target cell ratio in the presence of 100 ng/ml S239D/I332E trastuzumab. Cells then were treated with secondary Abs anti-CD11-RPE and anti-CD14-RPE (DAKO) for 15 min before live cell imaging using a Nikon Eclipse TS100 fluorescence microscope. For quantitative ADCP, target cells (SkBr3 for trastuzumab and WIL2-S for rituximab) were labeled with PKH67, seeded in a 96-well plate at 20,000 cells per well, and treated with WT or variant Ab at the designated final concentrations. Macrophages were labeled with PKH26 (Sigma) and added to the opsonized labeled target cells at 20,000 cells per well, and the cells were cocultured for 18 h. Fluorescence was measured by using dual-label flow cytometry at the City of Hope Flow Cytometry Unit (Duarte, CA).

For CDC assays, target WIL2-S lymphoma cells were washed 3× in 10% FBS medium by centrifugation and resuspension and seeded at 50,000 cells per well. WT or variant rituximab Ab was added at the indicated final concentrations. Human serum complement (Quidel, San Diego) was diluted 50% with medium and added to Ab-opsonized target cells. Final complement concentration was one-sixth original stock. Plates were incubated for 2 h at 37°C, Alamar Blue was added, cells were cultured for 2 days, and fluorescence was measured. Data were normalized to the maximum and minimum signal and fit to a sigmoidal dose-response curve.

In Vivo B Cell Depletion.

Monkey studies were conducted at Charles River Laboratories, Sierra Biomedical Division. Cynomolgus monkeys (Macaca fascicularis) were injected i.v. once daily for 4 consecutive days with WT or S239D/I332E rituximab Ab. The experiment comprised six treatment groups of ≈0.2, 2, 7, or 34 μg/kg (S239D/I332E) or ≈2 or 34 μg/kg (WT control), with three monkeys per treatment group. Blood samples were acquired on two separate days before dosing (baseline) and at days 1, 2, 5, 15, and 28 after initiation of dosing. For each sample, cell populations were quantified with flow cytometry by using specific Abs against the following marker antigens: CD2+/CD20+ (all lymphocytes, sample purity/total B cells), CD20+ and CD40+ (B lymphocytes), CD3+ (T lymphocytes), CD3+/CD4+ (T helper lymphocytes), CD3+/CD8+ (T cytotoxic/suppressor lymphocytes), CD3−/CD16+ and CD3−/CD8+ (NK cells), and CD3−/CD14+ (monocytes). Absolute numbers of each cell type were determined by multiplying the proportion of cells expressing the indicated markers by the absolute lymphocyte count and/or absolute monocyte count (determined by standard hematological analysis). Percent B cell depletion was calculated by comparing B cell counts on the given day with the average of the two baseline measures for each animal.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank John Desjarlais, Steve Doberstein, and Art Chirino for intellectual contributions; Meridith Alden for assistance with DNA sequencing; and Marie Ary for help with the manuscript. We thank Lucy Brown (City of Hope Flow Cytometry Unit) for her assistance and Patrick Lappin (Charles River Laboratories) for guidance with the macaque study.

Abbreviations

- ADCC

Ab-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity

- ADCP

Ab-dependent cell-mediated phagocytosis

- CDC

complement-dependent cytotoxicity

- FcγR

Fcγ receptor

- LDH

lactate dehydrogenase

- NK

natural killer

- PBMC

peripheral blood mononuclear cell

- SPR

surface plasmon resonance.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: G.A.L., W.D., S.K., O.V., J.S.P., L.H., C.C., H.S.C., A.E., S.C.Y., J.V., D.F.C., R.J.H., and B.I.D. are employees of Xencor. All commercial affiliations, financial interests, and patent-licensing arrangements that could be considered to pose a financial conflict of interest regarding the submitted article have been disclosed.

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

References

- 1.Weiner L. M., Carter P. Nat. Biotechnol. 2005;23:556–557. doi: 10.1038/nbt0505-556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cohen-Solal J. F., Cassard L., Fridman W. H., Sautes-Fridman C. Immunol. Lett. 2004;92:199–205. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2004.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jefferis R., Lund J. Immunol. Lett. 2002;82:57–65. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2478(02)00019-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Raghavan M., Bjorkman P. J. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 1996;12:181–220. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.12.1.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sondermann P., Kaiser J., Jacob U. J. Mol. Biol. 2001;309:737–749. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Radaev S., Sun P. Mol. Immunol. 2002;38:1073–1083. doi: 10.1016/s0161-5890(02)00036-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clynes R. A., Towers T. L., Presta L. G., Ravetch J. V. Nat. Med. 2000;6:443–446. doi: 10.1038/74704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cartron G., Dacheux L., Salles G., Solal-Celigny P., Bardos P., Colombat P., Watier H. Blood. 2002;99:754–758. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.3.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weng W. K., Levy R. J. Clin. Oncol. 2003;21:3940–3947. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dall’Ozzo S., Tartas S., Paintaud G., Cartron G., Colombat P., Bardos P., Watier H., Thibault G. Cancer Res. 2004;64:4664–4669. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-2862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Duncan A. R., Woof J. M., Partridge L. J., Burton D. R., Winter G. Nature. 1988;332:563–564. doi: 10.1038/332563a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sarmay G., Lund J., Rozsnyay Z., Gergely J., Jefferis R. Mol. Immunol. 1992;29:633–639. doi: 10.1016/0161-5890(92)90200-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Redpath S., Michaelsen T. E., Sandlie I., Clark M. R. Hum. Immunol. 1998;59:720–727. doi: 10.1016/s0198-8859(98)00075-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shields R. L., Namenuk A. K., Hong K., Meng Y. G., Rae J., Briggs J., Xie D., Lai J., Stadlen A., Li B., et al. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:6591–6604. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009483200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shields R. L., Lai J., Keck R., O’Connell L. Y., Hong K., Meng Y. G., Weikert S. H., Presta L. G. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:26733–26740. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202069200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cartron G., Watier H., Golay J., Solal-Celigny P. Blood. 2004;104:2635–2642. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-03-1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marshall S. A., Lazar G. A., Chirino A. J., Desjarlais J. R. Drug Discov. Today. 2003;8:212–221. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6446(03)02610-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kabat E. A., Wu T. T., Perry H. M., Gottesman K. S., Foeller C. Sequences of Proteins of Immunological Interest. Bethesda: U.S. Dept. of Health and Hum. Serv; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nieba L., Krebber A., Pluckthun A. Anal. Biochem. 1996;234:155–165. doi: 10.1006/abio.1996.0067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Edwards P. R., Leatherbarrow R. J. Anal. Biochem. 1997;246:1–6. doi: 10.1006/abio.1996.9922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Okazaki A., Shoji-Hosaka E., Nakamura K., Wakitani M., Uchida K., Kakita S., Tsumoto K., Kumagai I., Shitara K. J. Mol. Biol. 2004;336:1239–1249. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vogel C. L., Cobleigh M. A., Tripathy D., Gutheil J. C., Harris L. N., Fehrenbacher L., Slamon D. J., Murphy M., Novotny W. F., Burchmore M., et al. J. Clin. Oncol. 2002;20:719–726. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.3.719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ross J. S., Fletcher J. A., Linette G. P., Stec J., Clark E., Ayers M., Symmans W. F., Pusztai L., Bloom K. J. Oncologist. 2003;8:307–325. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.8-4-307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ernst L. K., Metes D., Herberman R. B., Morel P. A. J. Mol. Med. 2002;80:248–257. doi: 10.1007/s00109-001-0294-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Amigorena S., Bonnerot C. Semin. Immunol. 1999;11:385–390. doi: 10.1006/smim.1999.0196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thommesen J. E., Michaelsen T. E., Loset G. A., Sandlie I., Brekke O. H. Mol. Immunol. 2000;37:995–1004. doi: 10.1016/s0161-5890(01)00010-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Idusogie E. E., Presta L. G., Gazzano-Santoro H., Totpal K., Wong P. Y., Ultsch M., Meng Y. G., Mulkerrin M. G. J. Immunol. 2000;164:4178–4184. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.8.4178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reff M. E., Carner K., Chambers K. S., Chinn P. C., Leonard J. E., Raab R., Newman R. A., Hanna N., Anderson D. R. Blood. 1994;83:435–445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Warren H. S., Kinnear B. F. J. Immunol. 1999;162:735–742. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Regnault A., Lankar D., Lacabanne V., Rodriguez A., Thery C., Rescigno M., Saito T., Verbeek S., Bonnerot C., Ricciardi-Castagnoli P., Amigorena S. J. Exp. Med. 1999;189:371–380. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.2.371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rafiq K., Bergtold A., Clynes R. J. Clin. Invest. 2002;110:71–79. doi: 10.1172/JCI15640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kalergis A. M., Ravetch J. V. J. Exp. Med. 2002;195:1653–1659. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dhodapkar K. M., Krasovsky J., Williamson B., Dhodapkar M. V. J. Exp. Med. 2002;195:125–133. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dhodapkar M. V., Krasovsky J., Olson K. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:13009–13013. doi: 10.1073/pnas.202491499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Groh V., Li Y. Q., Cioca D., Hunder N. N., Wang W., Riddell S. R., Yee C., Spies T. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:6461–6466. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501953102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Uchida J., Hamaguchi Y., Oliver J. A., Ravetch J. V., Poe J. C., Haas K. M., Tedder T. F. J. Exp. Med. 2004;199:1659–1669. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vugmeyster Y., Howell K. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2004;4:1117–1124. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2004.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Preithner S., Elm S., Lippold S., Locher M., Wolf A., Silva A. J., Baeuerle P. A., Prang N. S. Mol. Immunol. 2006;43:1183–1193. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2005.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dahiyat B. I., Mayo S. L. Protein Sci. 1996;5:895–903. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560050511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Raha K., Wollacott A. M., Italia M. J., Desjarlais J. R. Protein Sci. 2000;9:1106–1119. doi: 10.1110/ps.9.6.1106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Leppers-van de Straat F. G., van der Pol W. L., Jansen M. D., Sugita N., Yoshie H., Kobayashi T., van de Winkel J. G. J. Immunol. Methods. 2000;242:127–132. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(00)00240-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.