Abstract

Previously we have reported in vitro evidence suggesting that that H2O2 may support wound healing by inducing VEGF expression in human keratinocytes (JBC 277: 33284–90). Here, we test the significance of H2O2 in regulating wound healing in vivo. Using the Hunt-Schilling cylinder approach we present first evidence that the wound site contains micromolar concentration of H2O2. At the wound site, low concentrations of H2O2 supported the healing process especially in p47phox and MCP-1 deficient mice where endogenous H2O2 generation is impaired. Higher doses of H2O2 adversely influenced healing. At low concentrations, H2O2 facilitated wound angiogenesis in vivo. H2O2 induced FAK phosphorylation both in wound-edge tissue in vivo as well as in human dermal microvascular endothelial cells (HMEC). H2O2 induced site-specific (Tyr-925 & Tyr-861) phosphorylation of FAK. Other sites, including the Tyr-397 autophosphorylation site, were insensitive to H2O2. Adenoviral gene delivery of catalase impaired wound angiogenesis and closure. Catalase over-expression slowed tissue remodeling as evident by a more incomplete narrowing of the hyperproliferative epithelium region and incomplete eschar formation. Taken together, this work presents the first in vivo evidence indicating that strategies to influence the redox environment of the wound site may have a bearing on healing outcomes.

Keywords: trauma, hydrogen peroxide, redox signaling, oxygen

Introduction

Disrupted vasculature limits the supply of oxygen to the wound-site. Compromised tissue oxygenation or wound hypoxia is viewed as a major factor that limits the healing process as well as wound disinfection [1]. The general consensus is that, at the wound site, oxygen fuels tissue regeneration [2] and that oxygen-dependent respiratory burst is a primary mechanism to resist infection [3]. We postulated that oxygen-derived reactive species at the wound site not only disinfects the wound but directly contributes to facilitate the healing process [4].

Wound healing commences with blood coagulation followed by infiltration of neutrophils and macrophages at the wound site to release reactive oxygen species (ROS) by oxygen-consuming respiratory burst. In 1999, the cloning of mox1 (later named as Nox1) marked a major progress in categorically establishing the presence of distinct NADPH oxidases in non-phagocytic cells [5]. Taken together, the wound-site has two clear sources of ROS: (i) transient delivery of larger amounts by respiratory burst of phagocytic cells; and (ii) sustained delivery of lower amounts by enzymes of the Nox/Duox family present in cells such as the fibroblasts, keratinocytes and endothelial cells. Recent studies show that, at low concentrations, ROS may serve as signaling messengers in the cell and regulate numerous signal transduction and gene expression processes [6]. Inducible ROS generated in some non-phagocytic cells are implicated in mitogenic signaling [7]. A direct role of NADPH oxidases and ROS in facilitating angiogenesis has been proven [8]. In line with these observations we have previously reported that at the wound site, ROS may promote wound angiogenesis by inducing VEGF expression in wound-related cells such as keratinocytes and macrophages [9]. In this study, we tested the significance of ROS in the healing of experimental dermal wounds.

Materials and Methods

Materials

AdLacZ and AdCatalase viral vectors were provided by Dr. John F. Engelhardt of Iowa University. CDC-HMEC-1 cells (SV40 T antigen transformed human microvascular endothelial cells) were provided by the Center for Disease Control (CDC Atlanta, GA) [10]. The p47phox KO mice were provided by Dr. S. Holland, NIAID, NIH and MCP-1−/− mice were obtained from Dr. B.J. Rollins, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York, NY. Unless otherwise stated all other chemicals and reagents were obtained from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO) and were of the highest grade available.

Secondary-intention excisional dermal wound model

Young male (8 weeks of age) C57Bl/6 mice were used. Two 8 x 16 mm full-thickness excisional wounds [9] were placed on the dorsal skin, equidistant from the midline and adjacent to the four limbs (Fig 2). The animals were killed at the indicated time and wound edges were collected for analyses. For wound-edge harvest, 1–1.5 mm of the tissue from the leading edge of the wounded skin was excised around the entire wound. “Hunt/Schilling” cylinder for wound fluid collection. The implantation of wire mesh cylinder (stainless steel; 2.5 cm length & 0.8 cm diameter) and wound fluid harvest was performed as described previously [11]. While this approach is a powerful tool to investigate wound fluid composition, most studies have used to it for wound fluid studies with time-points 1 week to 3 weeks following implantation. This is because of limitations in the volume of wound fluid available for harvest at earlier time-points. We have standardized techniques to harvest wound fluid as soon as day 2 after implantation. Catalase gene transfer. Because of potential hazards involved in viral gene delivery to open wounds, intact skin in each of the two wound sites were subcutaneously injected (1011 CFU) using a Hamilton gas-tight syringe with a 28G needle [12] with either AdCat (catalase) or AdLacZ (control) 5d prior to wounding. All animal protocols were approved by Institutional Lab Animal Care and Use Committee (ILACUC) of the Ohio State University. Determination of wound area. Imaging of wounds was performed using a digital camera (Mavica FD91, Sony). The wound area was determined using WoundMatrix™ software as described previously [9].

Figure 2. Topical H2O2 and wound closure.

Two 8 x 16 mm full-thickness excisional wounds (inset, day 0, A) were placed on the dorsal skin of mice. Each of the two wounds was topically treated either with H2O2 or saline A. Low-dose of H2O2 (1.25 micromoles/wound; or 0.025 ml of 0.15% or 50 mM solution/wound; once daily, days 0–4, open circles, ○) treatment facilitated closure moderately compared to placebo saline treated (closed circles, •) side. n=6; *, p< 0.05. B. Low dose H2O2 treatment does not influence wound microflora. For determination of surface microflora, wounds (treated with either 1.25 micromole H2O2/wound, open bar, or saline, closed bar) were swabbed (24–48 h post wounding. For deep tissue wound microflora, 48h after wounding eschar tissue was removed, wound bed tissue underneath eschar was sampled and quantitative assessment of bacterial load was performed. Values shown represent mean±SD of CFU of three observations. C. High dose (high, 25 micromoles/wound; closed circles, •, 0.025 ml of 3% solution versus low, 1.25 micromoles/wound or 0.025 ml of 0.15%; open circles, ○, once daily days 0–4, of H2O2 adversely affected closure. *, p< 0.05; compared to low dose H2O2 treatment. D. Comparison of the outcomes of high dose H2O2 treatment (C) with placebo treated wounds (A) in different mice. Compared to placebo saline (open circles, ○, once daily days 0–4) treatment, high dose H2O2 (closed circles, •, 0.025 ml of 3% H2O2) adversely affected closure. n=6; *, p< 0.05.

ROS detection in wounds

O2−. detection

Freshly frozen, enzymatically intact, 30-μm-thick sections of wound edge were incubated with DHE (10 μM) in PBS for 30 minutes at 37°C protected from light. DHE, oxidized to ethidium, was detected using a confocal microscope equipped with a 543-nm He-Ne laser and 560-nm long-pass filter was used [13]. This approach has been effectively utilized to test superoxide production in intact tissue section which in turn may also be interpreted as a measure of NADPH oxidase in the tissue [13].

Direct H2O2 measurements

H2O2 levels in wound fluid were measured using a real-time electrochemical H2O2 measurement as described [14]. The Apollo 4000 system (WPI, Sarasota, FL) was used for analysis. H2O2 was measured using the ISO-HPO-2 2.0 mm stainless steel sensor, with replaceable membrane sleeves and an internal refillable electrolyte. This electrode technology includes a H2O2 sensing element and separate reference electrode encased within a single Faraday-shielded probe design (WPI, Sarasota, FL). Catalase-sensitive signal provided a measure of H2O2.

Assessment of microbial (bacterial) growth in wounds

Superficial bacterial load

After 24 or 48 h after wounding, the surface was swabbed for 20 sec using an alginate-tipped applicator. Serial dilution of quantitative swabs was performed and plated on sterile agar medium. After 24h at 37°C in air ambience, the plates were examined and colonies were counted [15]. Deep tissue bacterial load: The superficial eschar tissue was removed. The wound bed tissue underneath eschar was excised aseptically, weighed, homogenized, serially diluted and cultured on agar plates as described above [16].

Cells and cell culture

HMEC-1 cells were cultured in MCDB-131 growth medium (GIBCO-BRL) supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 IU/mL penicillin, 0.1 mg/mL streptomycin, 2 mol/L L-glutamine [17].

RNAse protection assay

Total RNA was isolated from wound-edge tissue, snap frozen in liquid nitrogen, using Trizol reagent according to standard instructions provided by the manufacturer (Gibco BRL). RNAase protection assay was performed utilizing DNA templates from BD Pharmingen (BD RiboQuant™, San Diego, CA) using standard procedures [9].

Wound-site functional angiogenesis

Wound vascularity

Before sacrifice of mice, space-filling carboxylate-modified fluorescent microspheres (FluoSpheres, 0.2 μm, 1012 particles/ml) were injected into the left ventricle of the beating heart [18]. Wound-edge tissues were embedded in OCT. Cryosections (10 μm) fixed in acetone were analyzed by fluorescence microscopy. Blood flow imaging. The MoorLDI™-Mark 2 laser Doppler blood perfusion imager (Moor Instruments Ltd., UK) was used to map tissue blood flow.

Protein analyses

Wound-edge tissue was ground in liquid nitrogen and homogenized using a Teflon homogenizer in ice-cold RIPA lysis buffer containing protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma, MO) and 1 mM Na3VO4. The homogenate was centrifuged at 16,000 g at 4°C for 15 minutes. The supernatant was collected for further analyses. For preparation of cytosolic protein extract from monolayer cells, the culture media was aspirated and replaced by ice cold phosphate-buffered saline. Monolayers were scraped using cell lifter. The lifted cells were centrifuged at 4500 g for 5 mins at 4°C. After aspirating the supernatant, RIPA lysis buffer containing protease inhibitor cocktail and 1 mM Na3VO4 was added to the pellet. The suspension was vortexed and centrifuged for 10 mins at 16,000 g. The supernatant cytosolic extract was frozen at −80°C for further analyses. For catalase, FAK and phospho-FAK immunoblots, wound-edge tissue protein extract or cellular cytosolic extracts were separated on a 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel under reducing conditions, transferred to nitrocellulose and probed with anti-catalase (1: 30,000, Rockland, Gilbertsville, PA), anti-FAK (1:1000 dilution; Upstate Biotech, Lake Placid, NY), or anti-site specific phospho-FAK antibody (1:1000 dilution; Upstate Biotech, Lake Placid, NY). VEGF protein expression was determined using ELISA [9]. Catalase activity was assayed by monitoring the loss of absorbance of H2O2 at 240 nm. An extinction coefficient of 39.4 M−1.cm−1 was used for calculation of enzyme activity [19].

Histology

Formalin-fixed wound-edges embedded in paraffin were sectioned. The sections (4 μm) were stained with hematoxilin & eosin (H&E) using standard procedures or immunostained with the following primary antibodies: keratin14 (1:500; Covance, Berkeley, CA) or CD31 (1:200; BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA). To enable fluorescence detection, sections were incubated with appropriate Alexa Fluor® 488 (Molecular probes, Eugene, OR) conjugated secondary antibody (1:250 dilution).

Fluorescence image analyses: Tissue sections were analyzed by fluorescence microscopy (Axiovert 200M, Zeiss, Germany). Image analysis software (Axiovision 4.3, Zeiss, Germany) was used to quantitate fluorescence intensity (fluorescent pixels) of CD31 or fluorosphere positive areas (expressed as per mm2 area).

Statistics

In vitro data are reported as mean ± SD of at least three experiments. In vivo data from one wound of a mouse was compared to the other wound on the same mice using paired t-test. Comparisons among multiple groups were made by analysis of variance ANOVA. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Wound-site H2O2: generation and significance

We present first evidence demonstrating that wound fluid contains micromolar concentrations of steady-state H2O2 (Fig. 1). Of note, H2O2 levels were detected in both inflammatory as well as post-inflammatory phases i.e. days 2 and 5 post-wounding. In the murine model of full-thickness excisional wounds, macrophage infiltration is known to peak at day 3 post-wounding [20]. The H2O2 levels in the wound fluid was significantly higher during the inflammatory phase (day 2) compared to the post-inflammatory phase (day 5). Utilizing enzymatically intact frozen wound-edge tissue sections we compared the superoxide production between intact skin and the edge tissue of excisional dermal wound. Superoxide production in the wound-edge tissue was markedly more than that generated by the intact skin (Fig. 1b). Next, we sought to determine the functional significance of H2O2 at the wound site. We observed that topical application of low-dose H2O2 accelerated wound closure (Fig. 2A). H2O2, at relatively high concentrations, is known to be a wound disinfectant. Thus, we were led to question whether the beneficial effect of H2O2 was indeed wholly or partly mediated by the ability of H2O2 to cleanse the wound. Even under the stringent surgical conditions used in our study, a low bacterial load colonized the superficial dermal wound tissue. Importantly, H2O2 treatment did not affect such infection status. No bacterial infection was noted in the deep wound tissue (Fig. 2B). In surgical practice, the use of a strong solution (3%, v/v) of H2O2 to cleanse the wound has been common. H2O2, at high levels, is capable of inciting oxidative tissue damage and complicating regeneration of nascent tissue [21]. We observed that indeed, application of a low volume of 3% H2O2 to the wound significantly delayed wound closure (Fig. 2C & 2D). The use of an even stronger solution resulted in overt tissue damage leading to severe injury and death of mice (not shown). Taken together, these findings underscore the significance of the strength of H2O2 topically applied to wounds.

Figure 1. Presence of reactive oxygen species at the wound-site.

A. H2O2 concentration in wound fluid. Hunt-Schilling cylinders each were implanted in each of ten 8–10 weeks old C57BL/6 mice. On days 02 and 05, fluid was collected. Plasma, even in the presence of 200 mM NaN3 (added to inhibit peroxidase activity) H2O2 was below detection limits (ND, not detectable); Day 02 and Day 05, to discern the H2O2 –sensitive component of the signal detected in wound fluid 0.03 ml of the azide-free fluid was treated with 350 units of catalase. The catalase sensitive component was interpreted as H2O2. Standard curve was generated using authentic H2O2 tested for UV absorbance. n=4; *, p <0.01 compared to plasma value; †, p<0.01 compared to day 02. B. Superoxide production in normal skin and wound edge tissue. The skin or wound edge samples (n=3) were harvested at 12 h after wounding and immediately frozen in OCT. Fresh 30 micron sections were incubated with DHE (0.01mM, 20min) to detect O2.−. To demonstrate the specificity of DHE signal, superoxide dismutase (SOD, 10 U/ml) was added while incubating the wound edge samples with DHE. i) DHE (red) signal in excised skin tissue, ii) DHE signal in dermal wound edge 12h after wounding, iii) phase contrast image of ii, iv) DHE signal in wound edge in presence of 10U/ml superoxide dismutase, v) phase contrast image of iv. Scale bar = 100 μm.

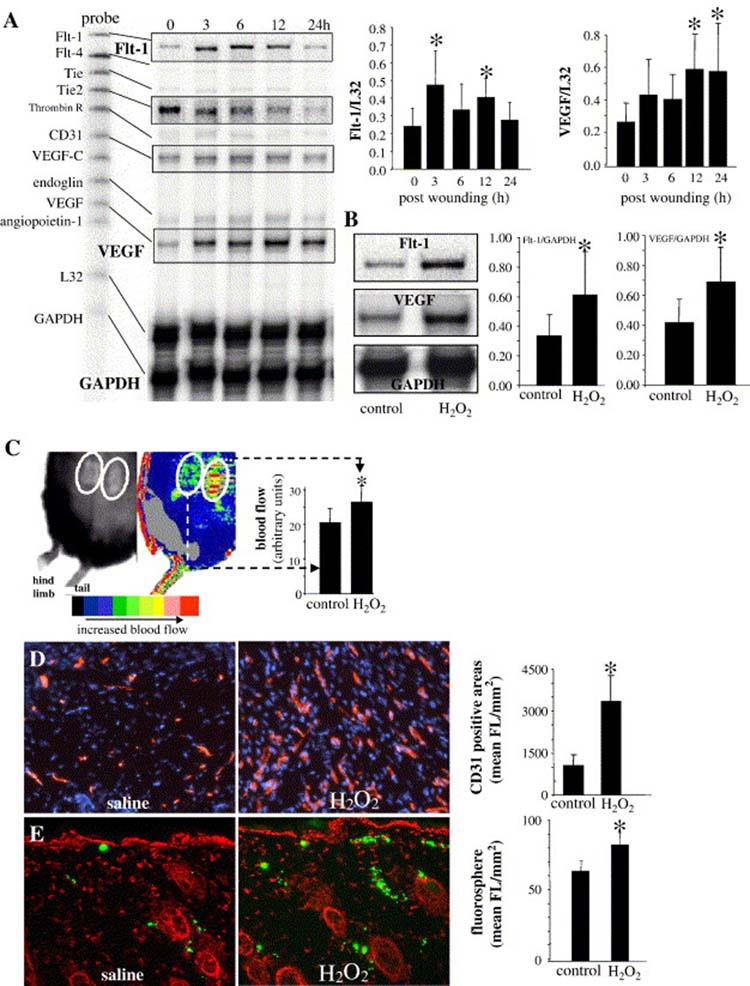

H2O2-induced angiogenic responses

Simultaneous study of a set of angiogenic genes using the quantitative ribonuclease protection assay approach demonstrated that VEGF and its receptor VEGFR1 or flt-1 is rapidly induced in response to healing. The inducible expression of these two genes was clearly specific, rapid and sustained (Fig. 3A). Topically applied low-dose H2O2 potentiated wound-induced VEGF and flt-1 expression in the wound-edge (Fig. 3B). Repeated topical treatment of one of the paired excisional dermal wounds improved blood flow (Fig. 3C). Immunohistological studies of the wound-edge tissue for the presence of endothelial cells provided consistent evidence supporting that low-dose H2O2 treatment was associated with increased abundance of endothelial cells (Fig. 3D) and vascularity (Fig. 3E) at the wound edge.

Figure 3. Wound and H2O2-induced changes in angiogenesis related genes, vascularization and wound-edge blood flow.

Paired excisional wounds (Figure 2) were either treated with placebo saline or H2O2 (1.25 micromole/wound, days 0–4, once daily). A. Ribonuclease protection assay showing kinetics of angiogenesis-related mRNA expression in a placebo saline-treated wound. Densitometry data (mean ± SD, n=4) are shown for Flt-1 and VEGF. *, p<0.05 compared to 0h. B. Low dose H2O2 treatment (1.25 micromole/wound, once at day 0) to wounds further augmented wound-induced Flt-1 and VEGF mRNA expressions as determined from wound-edge tissue harvested 6h after wounding and H2O2 treatment. Densitometry data (mean ± SD, n=4) are shown. *, p<0.05 compared to control. C. Blood flow imaging of wounds was performed non-invasively using laser Doppler. Images reflecting the blood flow (right panel) and a digital photo (region of interest; left panel) from post-heal (one day after complete wound closure) tissue are shown. Mean ± SD (n=3) is presented (bar graph; *, p<0.05). D. Day 8 post-wounding, wound-edge was cryosectioned and vascularization was estimated by staining for CD31 (red, rhodamine) and DAPI (blue, nuclei); higher abundance of CD31 red stain in section obtained from H2O2 treated side (right) demonstrate better vascularization versus control (left). Bar graph presents image analysis outcomes (mean ± SD, n=3). *, p<0.05 compared to control. E. Before sacrifice of mice on day 8 post-wounding, space-filling carboxylate-modified fluorescent microspheres were injected into the left ventricle of the beating heart to visualize neovascularization in the healing wound. Cryosections (10 μm) fixed in acetone and stained with DAPI (nuclei, shown here in contrast red) were analyzed by fluorescence microscopy. The appearance of the green microspheres at the wound edge represents wound vascularity. Bar graph presents image analysis outcomes (mean ± SD, n=3). *, p<0.05 compared to control.

H2O2-induced site-specific phosphorylation of FAK

FAK plays a central role in driving angiogenesis [22]. We observed that FAK phosphorylation is H2O2 inducible (Fig. 4A). Upon stimulation, FAK is phosphorylated on six tyrosine residues Tyr-397, Tyr-407, Tyr-576, Tyr-577, Tyr-861 and Tyr-925 [23]. Each of these sites have a specific functional significance and are subject to site-specific phosphorylation [24]. Tyr-925 phosphorylation of FAK within focal adhesions are known to support angiogenic responses [25]. In HMEC, the Tyr-925 and Tyr-861 sites was specifically phosphorylated in the presence of low concentration of H2O2 (Fig. 4B). H2O2 also induced FAK phosphorylation in the wound-edge in vivo (Fig. 4C).

Figure 4. H2O2-induced phosphorylation of focal adhesion kinase (FAK) in microvascular endothelial cells and wound edge tissue.

HMEC-1 were treated with H2O2 for the indicated dose and duration (n=3). Phosphorylation of FAK was detected using Western blot and phosphorylation site-specific antibodies against FAK. Native FAK was blotted to show equal loading. A. Effect of doses of H2O2 treatment on phosphorylation (Tyr 925) state of FAK. B. Kinetics of site-specific phosphorylation of FAK in HMEC cells following H2O2 (0.1 mM) treatment. C. Paired excisional wounds (Fig 2) were either treated with placebo saline or H2O2 (1.25 micromole/wound). Wound-edge tissue (n=3) was collected 30 min after wounding.

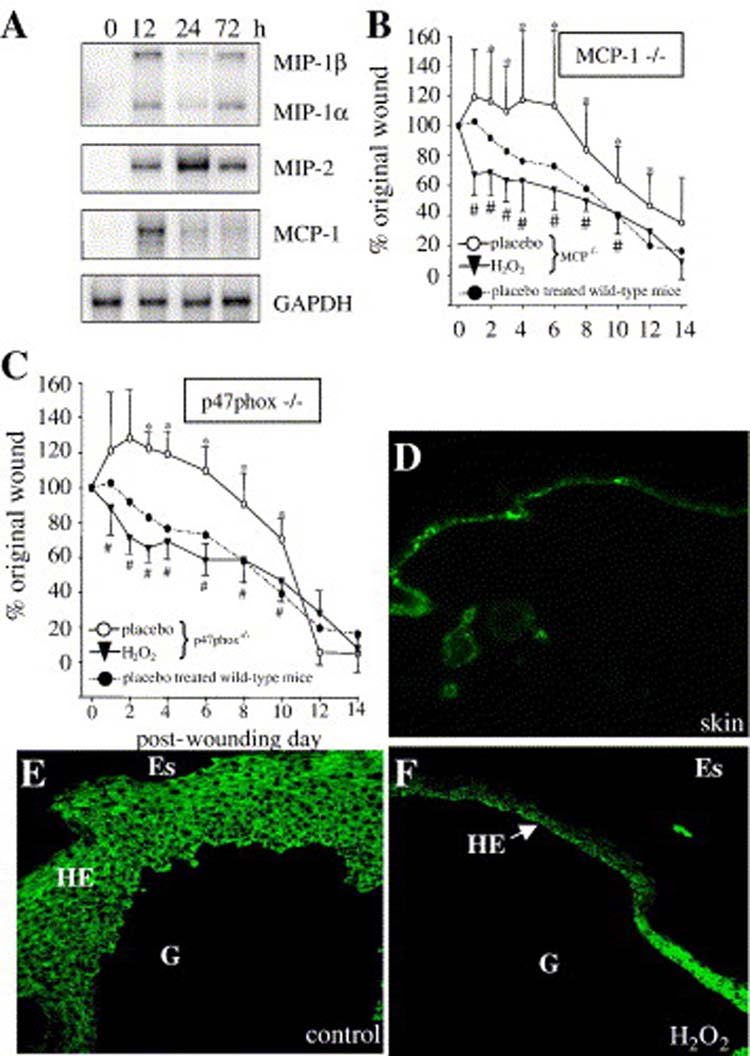

Physiological H2O2-delivery systems

Mice are very aggressive healers closing dermal defects as large as over 10% of their total body surface within 2 weeks time [9]. Thus, it is apparent that the basal healing machinery is highly efficient leaving little room for further acceleration of healing in wild-type mice. Dermal wounding results in rapid induction of genes encoding chemokines that recruit inflammatory cells to the wound site (Fig. 5A). Specific genetically altered mice that suffer from impaired healing serve as useful models to study the effects of agents that may promote wound closure and healing. Monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1) deficient mice suffer from impaired wound angiogenesis and healing [26]. In tissues, macrophages are known to be significant producers of H2O2 by the NADPH oxidase dependent respiratory burst mechanism [27]. We hypothesized that insufficient H2O2 production at the wound site of MCP-1 deficient mice was one factor that compromised wound angiogenesis and healing. Indeed, treatment of excisional dermal wounds in MCP-1 deficient mice with low-dose H2O2 completely corrected the rate of wound closure (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5. Role of H2O2 in MCP-1 and p47phox deficient mice.

Two excisional wounds (Fig 2) were placed on the dorsal skin of wild-type, MCP-1−/− or p47phox −/− mice. Each of the two wounds was treated with either saline or H2O2 (1.25 micromoles/wound; days 0–4). A. RPA showing kinetics of monocyte/macrophage chemotactic protein related mRNA expression in placebo saline-treated wounds of wild-type mice (n=3). B. Wound closures in saline (closed circles, •) treated wounds of C57BL/6 and H2O2 (closed triangles, ▾) or saline (open circles, ○) treated MCP-1−/− mice are shown. n=7; * p< 0.05; compared to C57BL/6 saline treatment. #, p< 0.05; compared to KO saline treatment. C. Wound closures in saline (closed circles, •) treated wounds of C57BL/6 and H2O2 (closed triangles, ▾) or saline (open circles, ○) or p47phox KO mice are shown. *p< 0.05; compared to C57BL/6 saline treatment. #, p< 0.05; compared to KO saline treatment. D. Keratin 14 (green fluorescence) expression in murine skin. E–F. Keratin 14 expression in skin of of p47phox KO mice harvested from wound sites after closure on day 18 post-wounding. Note higher expression of keratin 14 in control side (E) compared to H2O2-treated side (F) indicating healing is ongoing on the control side, while H2O2 treated side shows keratin 14 expression comparable to normal skin (D). For orientation (see histological identifying characteristics in Fig. 6C): Es, eschar; G, granulation tissue; HE, hyperproliferative epithelium.

NADPH oxidase is a key source of H2O2 in inflammatory cells [27]. Defect in the expression of any of the essential subunits of NADPH oxidase e.g., p47phox is expected to compromise respiratory burst dependent oxidant production. Mutations in p47phox are a cause of chronic granulomatous disease (CGD) in humans, an immune-deficient condition characterized with impaired healing response [28]. Consistently, p47phox deficient mice suffer from impaired healing. The abnormal wound closure in p47phox deficient mice was completely corrected in response to low-dose topical H2O2 treatment (Fig. 5C). Keratin 14 supports epidermal differentiation and regeneration [29] and its expression is triggered by dermal wounding [30]. In intact skin, keratin 14 is present as a narrow margin in the basal layer epidermis whereas in healing tissue keratin 14 is expressed as a broader band at the hyperproliferative epithelium [30]. Post-closure sampling of regenerated skin from the wound-site of p47phox deficient mice revealed that the low-dose H2O2 treated side not only closed faster but the regenerated skin resembled the keratin 14 distribution in intact skin. In contrast, the regenerated skin of the placebo saline-treated side showed signs of incomplete healing at a matched time point (Fig 5D).

Decomposition of endogenous wound-site H2O2 impairs wound healing

In vivo catalase gene transfer represents one productive approach to down-regulate tissue H2O2 levels [31]. Over-expression of catalase (Fig. 6A) down-regulated inducible early-phase VEGF expression at the wound-edge (Fig. 6B) consistent with our observations that H2O2 is a potent and prompt inducer of VEGF both in vitro [9] as well as in vivo (Fig 3B). Such early-phase effect of catalase expression did impair wound angiogenesis on a long-term basis. AdCat treated wound tissues had compromised blood flow (Fig. 6C) compared to the AdLacZ treated control wounds. Impairment of wound angiogenesis caused by catalase over-expression clearly limited wound closure (Fig. 6D) comparable to the kinetics of wound closure in p47phox deficient mice (Fig. 5C). Histological analysis of wound-edge tissue by trichrome staining substantiated that catalase over-expression did not only limit angiogenesis and slow wound closure but that the quality of regenerating tissue was distinctly affected. Catalase over-expression slowed tissue restructuring as evident by a more incomplete narrowing [9] of the hyperproliferative epithelium zone and incomplete eschar formation in the time-matched post-heal tissue (Fig. 6E).

Figure 6. Catalase over-expression impairs healing.

A. Western blot of infected (1011 CFU) skin showing catalase over-expression in the side treated with AdCatalase (AdCat) virus compared to the side treated with control AdLacZ virus. Blots were re-probed with β–actin to confirm equal loading of samples. Activity assay demonstrated that the AdCat approach was effective in significantly (*, p<0.05) increasing catalase activity in the tissue compared to the AdLacZ control. B, VEGF protein expression in wound-edge on day 1 post-wounding. C, Blood flow at the wound-site on day 6 post-wounding. Blood flow imaging of wounds was performed non-invasively using a laser Doppler blood flow imaging device as described in the legend of Fig. 3C. D. Dotted line represents standard healing curve of saline treated C57BL/6 mice (open circles, ○) without viral infection. AdCat treatment (closed triangles, ▾); AdlacZ treatment (closed circles, •); *p < 0.05, compared to LacZ treated side. E. Masson trichrome staining was performed on formalin fixed paraffin sections of regenerated skin at the wound-site sampled on the day both wounds closed. AdCat side (right) shows broader HE region indicative of incomplete (vs. control on left) regeneration of skin, consistent with slower closure. The wound-edge is marked with an arrow. Es, eschar; G, granulation tissue; HE, hyperproliferative epithelium.

DISCUSSION

Interest in the role of oxygen in wound healing spiked when Jacques Cousteau’s divers had anecdotally reported that they healed their work wounds significantly better when they lived in an undersea habitat about 35 feet under the surface of the Red Sea [32]. Research during the last four decades led to the consensus that limited supply of oxygen to the wound site represents a key limiting factor for healing. More recent research during the last decade substantiate that, in biological tissues, oxygen generates reactive derivatives commonly referred to as reactive oxygen species (ROS). While earlier works primarily focused on the damaging aspects of excess ROS, current research builds a compelling case supporting the role of ROS as diffusible signaling messengers [6]. The phagocytic (phox) and non-phagocytic (Nox) NADPH oxidases represent one of the most significant sources of deliberate ROS production in biological tissues. Respiratory burst in phagocytic cells results in transient generation of excess ROS designed to kill pathogens [4]. In contrast, Nox generates low levels of ROS in fibroblasts on a sustained basis to drive a wide variety of biological processes including angiogenesis [33]. This work provides the first estimation of ROS concentration at the wound site in vivo. Our observation that the wound site is enriched in H2O2 is consistent with previous observation in plants recording that endogenous H2O2 levels increase in wounded leaves [34].

The wound site starts to be occupied by the granulation tissue approximately four days after injury. New capillaries primarily contribute to the granular appearance. Macrophages, fibroblasts and blood vessels are major components of the granulation tissue. Guided by products contributed by macrophages wound angiogenesis picks pace. Basic fibroblast growth factor (FGF2) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) are two key facilitators of wound angiogenesis. Other growth factors such as platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), TGFβ and insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF1) prepare the fibroblasts to participate in the formation of granulation tissue [4]. H2O2 enhances the affinity of FGF2 for its receptor [35]. In addition, ROS induces FGF2 expression [36]. H2O2 induces VEGF expression in wound related cells [9]. VEGF is believed to be the most prevalent, efficacious and long-term signal that is known to stimulate angiogenesis in wounds [37]. Recently it has been demonstrated that Nox1-derived ROS is a potent trigger of the angiogenic switch, increasing vascularity and inducing molecular markers of angiogenesis. Nox1 also induces matrix metalloproteinase activity, another marker of the angiogenic switch. Nox1-dependent induction of VEGF is eliminated by co-expression of catalase, indicating that H2O2 signals for the switch to the angiogenic phenotype [33]. Vascular endothelial growth factor receptors (VEGFR) are considered essential for angiogenesis. The VEGFR-family proteins consist of VEGFR-1/Flt-1, VEGFR-2/KDR/Flk-1, and VEGFR-3/Flt-4. In contrast to VEGF and its receptor VEGFR-2, placental growth factor (PlGF) and its receptor VEGFR-1 have been largely neglected. VEGFR-1 plays an important role in the angiogenic switch. VEGFR1 or Flt-1 is effective in the growth of new and stable vessels in cardiac and limb ischemia, through its action on endothelial, smooth muscle and inflammatory cells and their precursors [38]. Our results indicate that the expression of VEGFR1 in the wound-edge tissue is sensitive to low-dose H2O2 treatment. This observation is consistent with the report demonstrating that the expression of VEGFR1/Flt-1 is highly induced in H2O2-rich vascular cells in Nox1-expressing tumors [33].

FAK is a positive regulator of both cell motility, cell survival and may contribute to the development of a stable neo-vasculature. FAK signaling results from its ability to become highly phosphorylated in response to external stimuli. The major site of autophosphorylation, tyrosine 397, is a docking site for the SH2 domains of Src family proteins. The other sites of phosphorylation are phosphorylated by Src kinases. We observed that both in HMEC as well as in the wound-edge tissue, tyrosine 925 in FAK is specifically phosphorylated in response to low-dose H2O2. This observation is consistent with the established finding that c-Src kinase activity is H2O2-inducible [39]. FAK is subject to site-specific phosphorylation [24]. Our observation that H2O2 induced phosphorylation of FAK is site-specific is in agreement. Previously it has been reported that stimulation of FAK by low-density lipoprotein results in specific phosphorylation of Tyr-925 phosphorylation surpassing the phosphorylation of the other residues, including Tyr-397 [24]. Our studies with HMEC point towards Tyr-925 and Tyr-861 as being sensitive to H2O2. Indeed, site-specific phosphorylation of FAK at the 861 and 925 Tyr sites have been observed to share common mechanisms [40]. Activation of FAK may support angiogenesis by a number of mechanisms including the formation of actin stress fibers/focal adhesions [41], strengthening of endothelial barrier [42], facilitating VEGF signaling [43,44] and mediating integrin-sensitive signaling pathways [23]. Recently, direct proof support that vascular defects in FAK−/− mice result from the inability of FAK-deficient endothelial cells to organize themselves into vascular networks [22],

Just hours after injury, the wound site recruits inflammatory cells. MCP-1 deficient mice recruit fewer phagocytic macrophages to the injury site [45]. In addition, the macrophages that are recruited suffer from compromised functionality [26]. MCP-1 is angiogenic in vivo [46]. At the wound site, macrophages deliver numerous angiogenic products [47] including H2O2 [27]. Our observation that impairment of dermal wound healing in MCP-1 deficient mice [26] may be completely abrogated by topical low-dose H2O2 treatment point towards a central role of inflammatory cell derived H2O2 in promoting wound closure. Supporting data from experiments with mice containing defective NADPH oxidase, the primary enzyme responsible for H2O2 generation by inflammatory cells, lend additional strength to the notion that endogenously generated H2O2 at the wound site is a key factor in wound healing. Mutations in p47phox are a cause of CGD in humans, an immune-deficient condition characterized with impaired healing response [28]. The p47phox−/− mouse exhibits a phenotype similar to that of human CGD [48]. p47phox deficiency impairs NADPH oxidase dependent H2O2 formation [49]. We have observed that wild-type mice are capable of generating significant amounts of H2O2 at the wound-site. Thus, the beneficial effects of additional topical H2O2 in such mice were only modest. However, in p47phox deficient mice suffering from compromised ability to generate wound-site H2O2 the effects of topical 0.15% H2O2 were more striking in. In vivo catalase gene transfer is one approach by which the effects of endogenous H2O2 are assessed. Catalase-dependent removal of endogenous H2O2 at the wound site resulted in a clear adverse effect on healing outcome. This observation, taken together with the result that topical H2O2 facilitates dermal wound healing, point towards a clear role of H2O2 as a messenger for dermal wound healing.

Over the counter, H2O2 is commonly available at strength of 3%. Historically, at such strength H2O2 have been clinically used for disinfection of tissues [50]. The use of H2O2 to disinfect wounds continues today with a valid concern that at such high doses H2O2 may hurt nascent regenerating tissues [21]. Indeed, we observed no beneficial effect of 3% H2O2.This work presents first evidence suggesting that at the wound-site, low levels of H2O2 are generated. At such μM levels, H2O2 drives redox-sensitive signaling mechanisms. Although the current work focuses on H2O2-sensitive mechanisms underlying wound angiogenesis, it is important to note that redox-sensitive mechanisms may influence numerous aspects of dermal wound healing [4]. Topical application of 0.15% H2O2 favorably influenced wound angiogenesis. Chronic wounds are typically hypoxic and thus limited in their ability to generate endogenous H2O2. In addition, CGD patients are clearly impaired in their ability to generate endogenous H2O2. For such cases, therapeutic strategies based on targeting the wound-site redox state may deliver.

Acknowledgments

Work supported by NIH RO1 GM69589 to CKS. Thanks to Drs. Srikanth Pendyala and Subhasis Banerjee for technical assistance.

References

- 1.Gordillo GM, Sen CK. Revisiting the essential role of oxygen in wound healing. Am J Surg. 2003;186:259–263. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(03)00211-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kivisaari J, Vihersaari T, Renvall S, Niinikoski J. Energy metabolism of experimental wounds at various oxygen environments. Annals of Surgery. 1975;181:823–828. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197506000-00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grief R, Akca O, Horn EP, Kurz A, Sessler DI. Supplemental perioperative oxygen to reduce the incidence of surgical-wound infection. Outcomes Research Group.[see comment] New England Journal of Medicine. 2000;342:161–167. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200001203420303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sen CK. The general case for redox control of wound repair. Wound Repair Regen. 2003;11:431–438. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-475x.2003.11607.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Suh YA, Arnold RS, Lassegue B, Shi J, Xu X, Sorescu D, Chung AB, Griendling KK, Lambeth JD. Cell transformation by the superoxide-generating oxidase Mox1. Nature. 1999;401:79–82. doi: 10.1038/43459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rhee SG. Redox signaling: hydrogen peroxide as intracellular messenger. Experimental & Molecular Medicine. 1999;31:53–59. doi: 10.1038/emm.1999.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Irani K, Xia Y, Zweier JL, Sollott SJ, Der CJ, Fearon ER, Sundaresan M, Finkel T, Goldschmidt-Clermont PJ. Mitogenic signaling mediated by oxidants in Ras-transformed fibroblasts. Science. 1997;275:1649–1652. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5306.1649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stone JR, Collins T. The role of hydrogen peroxide in endothelial proliferative responses. Endothelium. 2002;9:231–238. doi: 10.1080/10623320214733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sen CK, Khanna S, Babior BM, Hunt TK, Ellison EC, Roy S. Oxidant-induced vascular endothelial growth factor expression in human keratinocytes and cutaneous wound healing. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2002;277:33284–33290. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203391200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ades EW, Candal FJ, Swerlick RA, George VG, Summers S, Bosse DC, Lawley TJ. HMEC-1: establishment of an immortalized human microvascular endothelial cell line. J Invest Dermatol. 1992;99:683–690. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12613748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bentley JP, Hunt TK, Weiss JB, Taylor CM, Hanson AN, Davies GH, Halliday BJ. Peptides from live yeast cell derivative stimulate wound healing. Arch Surg. 1990;125:641–646. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1990.01410170089019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ozawa K, Kondo T, Hori O, Kitao Y, Stern DM, Eisenmenger W, Ogawa S, Ohshima T. Expression of the oxygen-regulated protein ORP150 accelerates wound healing by modulating intracellular VEGF transport. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:41–50. doi: 10.1172/JCI11772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sorescu D, Weiss D, Lassegue B, Clempus RE, Szocs K, Sorescu GP, Valppu L, Quinn MT, Lambeth JD, Vega JD, Taylor WR, Griendling KK. Superoxide production and expression of nox family proteins in human atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2002;105:1429–1435. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000012917.74432.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu X, Zweier JL. A real-time electrochemical technique for measurement of cellular hydrogen peroxide generation and consumption: evaluation in human polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Free Radic Biol Med. 2001;31:894–901. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(01)00665-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bill TJ, Ratliff CR, Donovan AM, Knox LK, Morgan RF, Rodeheaver GT. Quantitative swab culture versus tissue biopsy: a comparison in chronic wounds. Ostomy Wound Managent. 2001;47:34–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bowler PG, Duerden BI, Armstrong DG. Wound microbiology and associated approaches to wound management. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2001;14:244–269. doi: 10.1128/CMR.14.2.244-269.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mason JC, Yarwood H, Sugars KB, Morgan P, Davies KA, Haskard DO. Induction of decay-accelerating factor by cytokines or the membrane-attack complex protects vascular endothelial cells against complement deposition. Blood. 1999;94:1673–1682. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jacobi J, Jang JJ, Sundram U, Dayoub H, Fajardo LF, Cooke JP. Nicotine accelerates angiogenesis and wound healing in genetically diabetic mice. American Journal of Pathology. 2002;161:97–104. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64161-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aebi H. Catalase in vitro. Methods Enzymol. 1984;105:121–126. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(84)05016-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.DiPietro LA, Burdick M, Low QE, Kunkel SL, Strieter RM. MIP-1alpha as a critical macrophage chemoattractant in murine wound repair. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:1693–1698. doi: 10.1172/JCI1020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Branemark PI, Ekholm R. Tissue injury caused by wound disinfectants. Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery - American Volume. 1967;49:48–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ilic D, Kovacic B, McDonagh S, Jin F, Baumbusch C, Gardner DG, Damsky CH. Focal adhesion kinase is required for blood vessel morphogenesis.[see comment] Circulation Research. 2003;92:300–307. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000055016.36679.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cary LA, Guan JL. Focal adhesion kinase in integrin-mediated signaling. Frontiers in Bioscience. 1999;4:D102–113. doi: 10.2741/cary. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Relou IA, Bax LA, van Rijn HJ, Akkerman JW. Site-specific phosphorylation of platelet focal adhesion kinase by low-density lipoprotein. Biochemical Journal. 2003;369:407–416. doi: 10.1042/BJ20020410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shono T, Kanetake H, Kanda S. The role of mitogen-activated protein kinase activation within focal adhesions in chemotaxis toward FGF-2 by murine brain capillary endothelial cells. Experimental Cell Research. 2001;264:275–283. doi: 10.1006/excr.2001.5154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Low QE, Drugea IA, Duffner LA, Quinn DG, Cook DN, Rollins BJ, Kovacs EJ, DiPietro LA. Wound healing in MIP-1alpha(−/−) and MCP-1(−/−) mice. American Journal of Pathology. 2001;159:457–463. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)61717-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kinnula VL, Everitt JI, Whorton AR, Crapo JD. Hydrogen peroxide production by alveolar type II cells, alveolar macrophages, and endothelial cells. American Journal of Physiology. 1991;261:L84–91. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1991.261.2.L84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kume A, Dinauer MC. Gene therapy for chronic granulomatous disease. J Lab Clin Med. 2000;135:122–128. doi: 10.1067/mlc.2000.104458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reichelt J, Bussow H, Grund C, Magin TM. Formation of a normal epidermis supported by increased stability of keratins 5 and 14 in keratin 10 null mice. Mol Biol Cell. 2001;12:1557–1568. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.6.1557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Werner S, Werner S, Munz B. Suppression of keratin 15 expression by transforming growth factor beta in vitro and by cutaneous injury in vivo. Experimental Cell Research. 2000;254:80–90. doi: 10.1006/excr.1999.4726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hudde T, Comer RM, Kinsella MT, Buttery L, Luthert PJ, Polak JM, George AJ, Larkin DF. Modulation of hydrogen peroxide induced injury to corneal endothelium by virus mediated catalase gene transfer. British Journal of Ophthalmology. 2002;86:1058–1062. doi: 10.1136/bjo.86.9.1058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hunt TK, Ellison EC, Sen CK. Oxygen: at the foundation of wound healing--introduction. World Journal of Surgery. 2004;28:291–293. doi: 10.1007/s00268-003-7405-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Arbiser JL, Petros J, Klafter R, Govindajaran B, McLaughlin ER, Brown LF, Cohen C, Moses M, Kilroy S, Arnold RS, Lambeth JD. Reactive oxygen generated by Nox1 triggers the angiogenic switch. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2002;99:715–720. doi: 10.1073/pnas.022630199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Guan LM, Scandalios JG. Hydrogen-peroxide-mediated catalase gene expression in response to wounding. Free Radical Biology & Medicine. 2000;28:1182–1190. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(00)00212-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Herbert JM, Bono F, Savi P. The mitogenic effect of H2O2 for vascular smooth muscle cells is mediated by an increase of the affinity of basic fibroblast growth factor for its receptor. FEBS Letters. 1996;395:43–47. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00998-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pechan PA, Chowdhury K, Seifert W. Free radicals induce gene expression of NGF and bFGF in rat astrocyte culture. NeuroReport. 1992;3:469–472. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199206000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nissen NN, Polverini PJ, Koch AE, Volin MV, Gamelli RL, DiPietro LA. Vascular endothelial growth factor mediates angiogenic activity during the proliferative phase of wound healing. Am J Pathol. 1998;152:1445–1452. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Autiero M, Luttun A, Tjwa M, Carmeliet P. Placental growth factor and its receptor, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-1: novel targets for stimulation of ischemic tissue revascularization and inhibition of angiogenic and inflammatory disorders. Journal of Thrombosis & Haemostasis. 2003;1:1356–1370. doi: 10.1046/j.1538-7836.2003.00263.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Suzaki Y, Yoshizumi M, Kagami S, Koyama AH, Taketani Y, Houchi H, Tsuchiya K, Takeda E, Tamaki T. Hydrogen peroxide stimulates c-Src-mediated big mitogen-activated protein kinase 1 (BMK1) and the MEF2C signaling pathway in PC12 cells: potential role in cell survival following oxidative insults. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2002;277:9614–9621. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111790200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hauck CR, Hsia DA, Ilic D, Schlaepfer DD. v-Src SH3-enhanced interaction with focal adhesion kinase at beta 1 integrin-containing invadopodia promotes cell invasion. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2002;277:12487–12490. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100760200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim JS, Yu HK, Ahn JH, Lee HJ, Hong SW, Jung KH, Chang SI, Hong YK, Joe YA, Byun SM, Lee SK, Chung SI, Yoon Y. Human apolipoprotein(a) kringle V inhibits angiogenesis in vitro and in vivo by interfering with the activation of focal adhesion kinases. Biochemical & Biophysical Research Communications. 2004;313:534–540. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.11.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Quadri SK, Bhattacharjee M, Parthasarathi K, Tanita T, Bhattacharya J. Endothelial barrier strengthening by activation of focal adhesion kinase. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003;278:13342–13349. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209922200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Avraham HK, Lee TH, Koh Y, Kim TA, Jiang S, Sussman M, Samarel AM, Avraham S. Vascular endothelial growth factor regulates focal adhesion assembly in human brain microvascular endothelial cells through activation of the focal adhesion kinase and related adhesion focal tyrosine kinase. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003;278:36661–36668. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301253200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Abedi H, Zachary I. Vascular endothelial growth factor stimulates tyrosine phosphorylation and recruitment to new focal adhesions of focal adhesion kinase and paxillin in endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:15442–15451. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.24.15442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hughes PM, Allegrini PR, Rudin M, Perry VH, Mir AK, Wiessner C. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 deficiency is protective in a murine stroke model. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism. 2002;22:308–317. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200203000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Salcedo R, Ponce ML, Young HA, Wasserman K, Ward JM, Kleinman HK, Oppenheim JJ, Murphy WJ. Human endothelial cells express CCR2 and respond to MCP-1: direct role of MCP-1 in angiogenesis and tumor progression. Blood. 2000;96:34–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Crowther M, Brown NJ, Bishop ET, Lewis CE. Microenvironmental influence on macrophage regulation of angiogenesis in wounds and malignant tumors. Journal of Leukocyte Biology. 2001;70:478–490. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jackson SH, Gallin JI, Holland SM. The p47phox mouse knockout model of chronic granulomatous disease. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 1995;182:751–758. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.3.751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Whitlock BB, Helgason C, Ambruso D, Fadok V, Bratton D, Henson PM, Li JM. Essential role of the NADPH oxidase subunit p47(phox) in endothelial cell superoxide production in response to phorbol ester and tumor necrosis factor-alpha.[comment] Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2002;277:5236–5246. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Washington EA. Instillation of 3% hydrogen peroxide or distilled vinegar in urethral catheter drainage bag to decrease catheter-associated bacteriuria. Biol Res Nurs. 2001;3:78–87. doi: 10.1177/109980040200300203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]