Abstract

Water hyacinth (Eichhornia crassipes (Mart.) Solms) is a prolific free floating aquatic macrohpyte found in tropical and subtropical parts of the earth. The effects of pollutants from textile wastewater on the anatomy of the plant were studied. Water hyacinth exhibits hydrophytic adaptations which include reduced epidermis cells lacking cuticle in most cases, presence of large air spaces (7~50 μm), reduced vascular tissue and absorbing structures. Textile waste significantly affected the size of root cells. The presence of raphide crystals was noted in parenchyma cells of various organs in treated plants.

Keywords: Eichhornia crassipes, Water hyacinth, Textile wastewater, Anatomical studies

INTRODUCTION

The water hyacinth (Eichhornia crassipes (Mart.) Solms) is a prolific free floating aquatic weed found in tropical and subtropical areas of the world and recognized to be very useful in domestic wastewater treatment (Dinges, 1976; Wolverton and McDonald, 1979). Phytoremediation used for removing heavy metals and other pollutants is a newly developed environmental protection technique. Extensive studies on freshwater resources decontamination revealed that some freshwater plants, among which is the water hyacinth growing prolific in wastewater, can efficiently accumulate heavy metals (Yahya, 1990; Vesk et al., 1999; Ali and Soltan, 1999; Soltan and Rashed, 2003). Water hyacinth has long been used commercially for cleaning wastewater. The luxuriant plant’s tremendous capacity for absorbing nutrients and other pollutants from wastewater has long been overlooked by many wastewater engineers. In recent years, the plant has been used to treat a variety of wastewaters and to produce high protein cattle food, pulp, paper, fiber, and more importantly, biogas as energy source (Agency for International Development, 1976; Bates and Hentges, 1976; Kojima, 1986).

Water hyacinth is a native of Brazil, and is introduced to and is naturalized in many tropical countries. Eichhornia crassipes (Mart.) Solms belongs to the taxonomic family Pontederiaceae. Wild perennial herb is 30~40 cm in length, with short stem and many long fibrous adventitious roots (Fig.1). Plants are floating, sometimes rooting (Fig.2).

Fig. 1.

Water hyacinth plants with roots

Fig. 2.

Water hyacinths growing in pond

In this paper, we describe the anatomical changes of this plant in relation to its growth in textile wastewater.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Collection of plants and textile effluents

The plant material used in this research i.e., water hyacinth, was collected from a natural pond near Jallo Park (10 km east of Lahore City, Pakistan). The plant is very common in Punjab Province especially in Gujranwala District, inhabiting vast marshy areas, propagating by stolons and multiplying very rapidly. The plants were stocked in a little pond in the Botanical Garden at Forman Christian College Campus, Lahore (Fig.2). Young plants were collected for this purpose. The effluent sample was collected from Cebee textile industries in Lahore, Pakistan.

Treatment of effluent with water hyacinth

The effluent was taken in triplicates for experimental setup. Nearly equal weight of water hyacinths i.e. 300 g fresh weight was added into 12-L tub containing textile effluents designated as experimental. In another set of 12-L tub equal weight of water hyacinths as in the experimental setup was added into tap water and was labelled as control. The experimental and control tubs were kept in green house for 96 h (Fig.3). The specific period plants were removed from the tubs and preserved for anatomical studies. The characteristics of typical textile wastewater as determined during the experiment are listed in Table 1.

Fig. 3.

Experimental setup

Table 1.

Characteristics of typical textile wastewater

| No. | Parameter | Range in textile wastewater |

| 1 | pH | 5.5~10.5 |

| 2 | COD (mg/L) | 350~700 |

| 3 | BOD (mg/L) | 150~350 |

| 4 | TDS (mg/L) | 1500~2200 |

| 5 | TSS (mg/L) | 200~1100 |

| 6 | Sulfides (mg/L) | 5~20 |

| 7 | Chlorides (mg/L) | 200~500 |

| 8 | Chromium (mg/L) | 2~5 |

| 9 | Zinc (mg/L) | 3~6 |

| 10 | Copper (mg/L) | 2~6 |

| 11 | Oil and grease (mg/L) | 10~50 |

| 12 | Sulfates (mg/L) | 500~700 |

| 13 | Sodium (mg/L) | 400~600 |

| 14 | Potassium (mg/L) | 30~50 |

COD: Chemical Oxygen Demand; BOD: Biological Oxygen Demand; TDS: Total Dissolved solids; TSS: Total suspended solids

Anatomical studies of water hyacinth

The plant parts i.e. rhizomes, roots, leaves and petioles harvested after 96 h were cut into 10~15 cm pieces and preserved in formalin-acetic acid-alcohol (FAA), a lethal chemical preservative. Manual sectioning was done to study the plant material in cross sections.

Epidermal peels scraped from adaxial and abaxial surfaces of leaves were obtained and studied. After sectioning, the material was stained in Safranine and Fast Green stains, and then mounted in a drop of glycerin jelly on glass slides. A cover slip was placed over them and observations were made. Each control plants were cut into at least 100 sections. The best five transverse sections were selected for study of anatomical characteristics.

Microscope with 10× ocular and 10×, 40× objectives was used for all observations. An ocular micrometer was used for all measurements. The data obtained from ocular micrometer were converted into microns (μ) with the use of stage micrometer after coinciding both micrometers. Data presented here is mean of five measurements taken for study. Camera Lucida was used to take field area images. The stomatal index was calculated by using the formula

| Stomatal index=S/S+E×100 | (1) |

, where, S=number of stomata and E=number of epidermal cells.

Stomatal frequency was calculated by multiplying the number of stomata by the field area of 0.0346 mm2.

Statistical analysis

Paired t-test was used to compare the parameters of control and experimental plants by using SPSS 11.5 (statistical package for social sciences) at 5% level of significance.

RESULTS

The anatomical features of root, rhizome, petiole and leaf were compared in plants growing under experimental and controlled conditions.

Epidermis of root

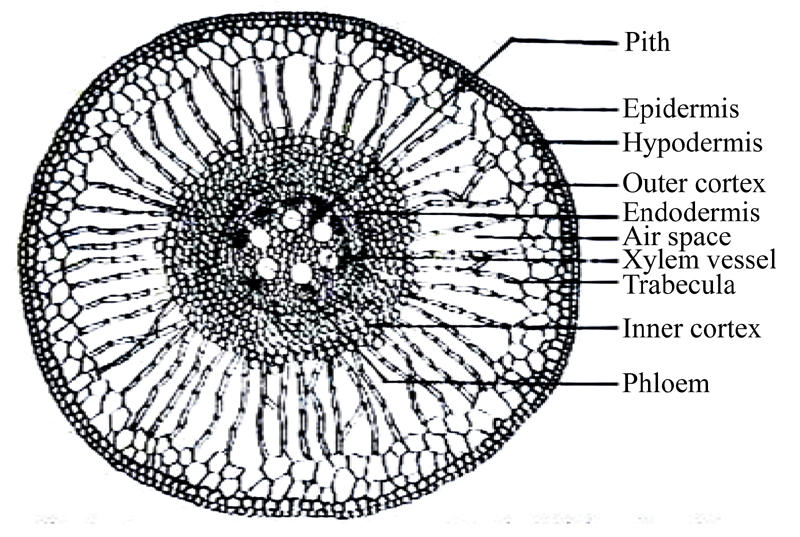

Root epidermis consists of single layered compactly arranged rectangular cells (Fig.4). There is no cuticle on the outside of root epidermis. Hypodermis is composed of 1~2 layers of thick-walled cells. Beneath the hypodermis cortex is differentiated into outer and inner cortex. The outer cortex is composed of 3~4 layered parenchymateous cells beneath the hypodermis. Each air space has trabeculae or partitions of parenchyma cells. The inner cortex consists of 6~10 layers of parenchymateous cells. There is no sclerenechyma cell in the cortex. The stele is surrounded on the outside by single layered endodermis where Casparian strips are not prominent. Beneath the endodermis is a single-layered pericycle. The stele consists of 7~10 xylem bundles alternating with phloem bundles. Each vascular bundle consists of a single metaxylem vessel (Fig.4) surrounded smaller vessels. The root center is occupied by sclerified parenchyma cells.

Fig. 4.

Cross section of the root of water hyacinth control plant (100×)

The following patterns were noted in the structure of roots grown in textile wastewater. Hypodermis consists of single layered thick-walled cells. The inner cortex consists of 4~6 layers of parenchymateous cells (Fig.5). The number of vascular bundles is 4~7. Raphide crystals of various sizes are observable in cortical cells. The average measured root cell sizes of experimental and control plants are listed in Table 2. Statistical analysis showed significant (P<0.05) differences between the average measurements of control and experimental plants for all the parameters of root cell sizes except endodermis.

Fig. 5.

Cross section of the root of water hyacinth experimental plant (100×)

Table 2.

Average measurements of cell sizes (μm) in roots of experimental and control plants

| Cell type | Control plant | Experimental plant | t-ratio | P-value |

| Epidermal cells | 4.0 | 3.5 | 3.536 | 0.024 |

| Hypodermis | 3.5 | 3.0 | 4.767 | 0.009 |

| Outer cortex | 7.0 | 6.0 | 8.771 | 0.001 |

| Parenchyma | 4.0 | 3.0 | 9.129 | 0.001 |

| Air spaces | 7.0 | 5.0 | 63.246 | 0.000 |

| Endodermis | 3.5 | 3.0 | 2.752 | 0.051 |

| Xylem vessels | 7.0 | 5.0 | 22.361 | 0.000 |

| Phloem cells | 3.5 | 2.0 | 6.283 | 0.003 |

| Pith | 4.0 | 3.0 | 14.142 | 0.000 |

Rhizome

The single layered epidermis is made of compactly arranged rectangular cells. The cortex beneath the epidermis consists of 4~6 layered “outer cortex” with cortical cells having dispersed different size vascular bundles surrounded on the outside by a patch of sclerenechyma. Air spaces are also prominent in this cortex. Xylem is V shaped. Phloem is present in between the arms of the xylem. Empty spaces or xylem cavities made up of lysed protoxylem elements are also visible (Fig.6). There is an inner portion of large air spaces separated from each other by a single cell layer of parenchyma. Air spaces are spherical. Vascular bundles are also present in the center of rhizome (Fig.6).

Fig. 6.

Cross section of rhizome of water hyacinth control plant (100×)

In plants grown in wastewater a large number of raphide crystals are visible in cortical cells. The outer cortex has 4~6 layers of parenchyma cells (Fig.7). Comparison of cell sizes in rhizomes of both control and experimental plants are given in Table 3. The cellular details of rhizome in experimental plants are illustrated in Fig.7. The measurements of cell sizes in rhizomes of control and experimental plants are shown in Table 3. The textile wastewater posed statistically significant (P<0.05) effect on the size of cells in rhizomes of experimental plants.

Fig. 7.

Cross section of rhizome of water hyacinth experimental plant (100×)

Table 3.

Average measurements of cell size (μm) in rhizomes of control and experimental plants

| Cell type | Control plant | Experimental plant | t-ratio | P-value |

| Epidermal cells | 4 | 3.0 | 7.255 | 0.002 |

| Cortex | 10 | 7.0 | 8.257 | 0.001 |

| Air spaces | 24 | 20.0 | 10.968 | 0.000 |

| Aerenchyma | 14 | 12.0 | 21.082 | 0.000 |

| Xylem (Tracheids) | 5 | 3.5 | 8.135 | 0.001 |

| Phloem (Sieve tubes) | 4 | 3.0 | 11.952 | 0.000 |

| Pith | 15 | 13.0 | 21.082 | 0.000 |

Petiole

Epidermis of petiole is also single layered and composed of parenchyma cells. Cuticle is absent. Vascular bundles are embedded in outer parenchyma cells. Each vascular bundle has a bundle cap of sclerenechyma cells (Fig.8) making up the petiole. The hexagonal air spaces are surrounded by bands of single layered parenchyma cells as shown in Fig.8.

Fig. 8.

Cross section of petiole of water hyacinth control plant (100×)

Vascular bundles are immersed in aerenchyma. Each vascular bundle has xylem tissue consisting of tracheids, vessels, parenchyma cells and fibers. Phloem is composed of sieve tubes and companion cells. Sclereids were observed arising from aerenchyma cells projecting into air spaces (Fig.8). A few raphides were also observed in parenchyma cells.

Plants grown in wastewater exhibited similar anatomical features except for a very large number of densely staining raphide crystals in parenchyma cells of the petiole (Fig.9). Differences in cell sizes are shown in Table 4. Statistical analysis showed that the textile wastewater had a non-significant (P>0.05) effect on the phloem elements only, while all other cells were significantly (P<0.05) reduced in size.

Fig. 9.

Cross section of petiole of water hyacinth experimental plant (100×)

Table 4.

Average measurements of cell size (μm) in petioles

| Cell type | Control plant | Experimental plant | t-ratio | P-value |

| Epidermal cells | 3.5 | 3.0 | 9.129 | 0.001 |

| Hypodermis | 5.0 | 4.0 | 10.541 | 0.000 |

| Smaller air spaces | 35.0 | 30.0 | 5.976 | 0.004 |

| Larger air spaces | 47.0 | 40.0 | 6.139 | 0.004 |

| Tracheids | 4.0 | 3.5 | 5.270 | 0.006 |

| Xylem cavity | 8.0 | 6.0 | 2.828 | 0.047 |

| Phloem cells | 3.0 | 2.5 | 1.890 | 0.132 |

| Parenchyma | 16.0 | 14.0 | 6.235 | 0.003 |

Leaf epidermis

Epidermal peels of leaves were studied. Trichomes are not observed in epidermis. Stomata are of paracytic type. The average size of guard cells was calculated to be 7 µm×4 µm, while the average size of the pore was 4 µm×4 µm. The stomata frequency on the upper epidermis was 2.83 mm2 and 3.32 mm2 on the lower epidermis. Thus the leaves are amphistomatic (Figs.10~11). Stomatal characteristics of epidermis in control and experimental plants are given in Tables 5~6. The experimental plants showed significant (P<0.05) reduction in the size of upper and lower epidermal cells, while the stomatal frequency and stomatal index in upper epidermis were not significantly affected.

Fig. 10.

Upper epidermis of leaf of water hyacinth experimental plant (400×)

Fig. 11.

Lower epidermis of leaf of water hyacinth experimental plant (400×)

Table 5.

Average stomatal characteristics of upper epidermis of control and experimental plants

| Plant | Stomatal pore (μm) | Guard cell |

Stomatal frequency (mm2) | Stomatal Index | |

| Length (μm) | Width (μm) | ||||

| Control | 4 | 7 | 4.0 | 2.83 | 20.68 |

| Experimental |

3 |

5 |

3.5 |

2.80 |

20.00 |

| t-ratio | 14.142 | 19.069 | 3.627 | 0.468 | 0.962 |

| P-value | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.022 | 0.664 | 0.391 |

Table 6.

Average stomatal characteristics of lower epidermis of control and experimental plants

| Plant | Stomatal pore (µm) | Guard cell |

Stomatal frequency (mm2) | Stomatal index | |

| Length (μm) | Width (μm) | ||||

| Control | 4 | 7 | 4.0 | 3.32 | 33.33 |

| Experimental |

3 |

5 |

3.5 |

2.83 |

22.22 |

| t-ratio | 12.910 | 31.623 | 4.564 | 26.192 | 1434.295 |

| P-value | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.010 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

Leaf anatomy

Transverse section of lamina has a very thin cuticle on the epidermal cells, which are rectangular in outline and form a single layer. The mesophyll is differentiated into a palisade and spongy mesophyll (Fig.12). Palisade layer is present on both upper and lower side beneath the epidermis. The upper epidermis has 5~7 layers of cells and the lower epidermis has 2~3 layers. Inside the palisade layer are densely staining material which may be supportive in nature (Fig.12). The spongy mesophyll consists of a large number of air spaces surrounded by thin walls full of chloroplast. Sclereids are observed in cells facing air spaces. Vascular bundles are of two types, i.e. smaller and larger vascular bundles. Smaller vascular bundles are present in both upper and lower epidermis side; some of them are in contact with the epidermis. Each vascular bundle is collateral with xylem towards the lower epidermis side and phloem towards the upper epidermis side. Tracheary elements consist of tracheids, vessels, and parenchyma cells. Tracheary elements in smaller bundles are thin-walled and without usual secondary thickenings. The phloem consists of sieve tubes and companion cells. Bundle sheath extensions are also observable in smaller bundles (Fig.12). Large vascular bundles are present in the leaf center and extend from one end to the other of the leaf (Fig.12). Each vascular bundle is surrounded by a bundle sheath of parenchyma cells. Sclereids are observable in the palisade cells, and also in air spaces. Some bundles have cross connections. Measurements of cell sizes in leaves of control and experimental plants are shown in Table 7. Statistical analysis showed that the textile wastewater had non-significant (P>0.05) effect on the palisade cells of leaves of the control and experimental plants, while all other cells were significantly (P<0.05) reduced in size.

Fig. 12.

Cross section of leaf of water hyacinth control plant (100×)

Table 7.

Average comparison of cell sizes (μm) in the cells of leaves of control and experimental plants

| Cell type | Control plant | Experimental plant | t-ratio | P-value |

| Epidermal cells | 6.0 | 5.0 | 5.345 | 0.006 |

| Palisade cells | 4.0 | 3.5 | 1.932 | 0.126 |

| Air spaces | 40.0 | 35.0 | 4.082 | 0.015 |

| Bundle sheath cells | 9.0 | 6.0 | 4.243 | 0.013 |

| Xylem cavity | 8.0 | 6.0 | 3.138 | 0.035 |

| Phloem cells | 3.5 | 3.0 | 3.835 | 0.019 |

| Parenchyma cells | 10.0 | 7.0 | 3.586 | 0.023 |

The palisade layer of the plants growing in the wastewater consists of 3~5 layers of cells towards the upper epidermis, and 1~2 layers of cells towards the lower side (Fig.13). Comparative cell sizes in control and experimental plant leaves are listed in Table 7. Numerous raphide crystals are observable in the experimental plants (Fig.13).

Fig. 13.

Cross section of leaf of water hyacinth experimental plant (100×)

DISCUSSION

The present work aimed at studying the anatomy of Eichhornia crassipes (Mart.) Solms after its interaction with textile wastewater for 96 h. So far no detailed work on the anatomy of Eichhornia crassipes is available. The anatomical features of plant studied show many hydrophytic adaptations.

The difference in structure and function of epidermis in hydrophytes as compared with that of plants growing in aerial habitat is outstanding. The epidermis is not protective in hydrophytes but absorbs gases and nutrients directly from water. Epidermis on all parts of water hyacinth consists of a single layer of rectangular cells which is characteristically a constant feature of this species. A very thin cuticle and thin cellulose walls of epidermal cells in a typical hydrophyte facilitate steady absorption from surrounding water.

The most pronounced anatomical feature of this plant is the presence of gas filled chambers and passages in roots, leaves and rhizome. Air chambers are large, usually regular (circular to hexagonal) intercellular spaces extending through leaf and long distances through stem. These chambers provide a sort of internal atmosphere for the plant. In these spaces oxygen emitted during photosynthesis is apparently stored and used again in respiration. Carbondioxide from respiration is accumulated and used in photosynthesis. The cross partition of air chambers are called diaphragms, perhaps for preventing flooding. Air chambers also give buoyancy to the organs in which they occur. The average size of air chambers ranges from 7~50 µm in various water hyacinth organs. Another type of tissue often found in aquatic plants gives buoyancy to plant parts on which it occurs is aerenchyma, formed by a typical phellogen of epidermal or cortical origin. In the physiological sense, aerenchyma is applied to tissue with many large intercellular spaces which seem to be a constant feature of this species.

An aquatic plant is actually submerged or floating on a nutrient solution. In the water hyacinth, structures that inland plants use to absorb minerals, nutrients and water from soil and conduct these substances through the plant are greatly reduced, and functioning chiefly as holdfasts. Considerable absorption takes place through stem (rhizome). The roots in water hyacinth are adventitious and lack root hairs (Nasir and Ali, 1977).

Xylem in the vascular system is reduced. There is usually a well developed lacuna in the xylem (Fig.9). Phloem though reduced in amount compared to mesophytes is fairly well developed as compared with xylem. It resembles the phloem of reduced herbaceous plants in that sieve tubes are smaller (3~5 μm) than those of woody plants. Endodermis is present usually though it is weakly developed. No Casparian strips found on endodermis, this finding is confirmed by earlier works of Barnabas (1996).

The treatment of textile wastewater with water hyacinth has some effects on the growth of the plant, the small size of which may be due to nutrient imbalance mainly of nitrogen in water (Thomas, 1983). High levels of salinity in wastewater can limit the growth of water hyacinth and other aquatic macrophytes (Sooknah and Wilkie, 2004).

CONCLUSION

The following conclusions can be drawn from the present study on the basis of the effect of textile wastewater on the anatomy of control and experimental plants.

1. The significant reduction in cell sizes in various plant organs may be due to arrested growth under stressed conditions as textile wastewater contains heavy metals and other toxic materials.

2. There are many raphide crystals in parenchyma cells of roots, petioles, rhizomes and leaves of treated plants.

3. The chemical content of water in which water hyacinth grows, significantly affects the plant size.

4. The raphide crystals in experimental plants may be of calcium oxalate as there is an accumulation of calcium content in plants. There is a need for further investigation of the anatomy of the plant as affected by wastewater.

Footnotes

Project (No. 30070017) supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China

References

- 1.Agency for International Development. Making Aquatic Weeds Useful, Some Perspectives for Developing Countries. Washington D.C.: National Tech. Inf. Ser.; 1976. No. PB161-225. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ali MM, Soltan ME. Heavy metals in aquatic macrophytes, water and hydrosoils from the river Nile. Egypt J Union Arab Biol. 1999;9:99–115. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barnabas AD. Casparian band like structures in the root hypodermis of some aquatic angiosperms. Aquatic Bot. 1996;55:217–225. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bates RP, Hentges JF. Aquatic weeds-eradicate or cultivate. Econ Bot. 1976;30:39–50. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dinges R. Water Hyacinth Culture for Wastewater Treatment. Austin, Texas, USA: Texas Department of Health Resources; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kojima T. Generation of methane gas from water hyacinth (Eichhornia crassipes), production of methane gas from combination of water hyacinth and fowl droppings. Bulletin of the Faculty of Agriculture, Saga University, Japan. 1986;61:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nasir E, Ali SI. Flora of West Pakistan. Vol. 114. Islamabad, Pakistan: National Agriculture Research Council; 1977. pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Soltan ME, Rashed MN. Laboratory study on the survival of water hyacinth under several conditions of heavy metal concentrations. Adv in Environ Res. 2003;7(2):82–91. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sooknah RD, Wilkie AC. Nutrient removal by floating aquatic macrophytes cultured in anaerobically digested flushed dairy manure wastewater. Ecological Engineering. 2004;22:27–42. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thomas KT. Studies on the Ecology of Aquatic Weeds in Karalla, India; Int. Conference on Water Hyacinth; Karala, India. 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vesk PA, Nockold CE, Aaway WG. Metal localization in water hyacinth roots from an urban wetland. Plant Cell Environ. 1999;22:149–158. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wolverton BC, McDonald RC. The water hyacinth: from prolific pest to potential provider. Ambio. 1979;8:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yahya MN. The absorption of metal ions by Eichhornia crassipes . Chem Speciation Bioavailability. 1990;2:82–91. [Google Scholar]