Scientific communication is in the process of metamorphosis. Will it change into a dung beetle or into a beautiful butterfly? Here is one possibility that some might argue is as frightening as Kafka's story

“As Gregor Samsa awoke from unsettling dreams one morning, he found himself transformed in his bed into a monstrous bug.”

Kafka, Metamorphosis

In 1995 we questioned the hallowed tenets of paper journals. We wrote a series of articles, beginning with “The death of biomedical journals,” suggesting the death knell for paper journals.1–3 Delamothe echoed our conclusions that “The burgeoning world wide web . . . makes it inevitable that new systems of disseminating research will replace or at least supplement journals.”4

Summary points

Traditional peer reviewed journals are becoming obsolete

We are experiencing a dramatic metamorphosis of the tools of scientific communication

The prima lingua of scientific communication is PowerPoint

Our search for the optimal information exchange method in science leads to P2P

The response was Kafkaesque, reminding us of the quote from Penal Colony “It is an exceptional apparatus” so do not question it. The “journal” apparatus shows that little of the fibre of journals has been scientifically evaluated. Are journals an efficient, scientific, “just in time” process? It is impossible to answer. For 300 years there has been no evidence based evaluation of the journal process. For example, there is virtually no research on the quality of learning from journals, whether IMRD (introduction, methods, results, discussion) optimises learning, or if traditional peer review is the best system. To quote Goldbeck-Wood, “But if peer review is so central to the process by which scientific knowledge become canonised, it is ironic that science has little to say as to whether it works.”5 This applies to all phases of the journal process.

Is a metamorphosis in sight? Delamothe said that systems such as E-biomed might be the new form.4,6 However, this has not caught on. We propose that the metamorphosis has furtively begun from a surprising and unrecognised direction.

“We all ask ourselves, What will happen?”

Kafka, An Old Leaf

Journals do not have an exclusive “right” to science. A publication and a scientific presentation do virtually the same thing—they share scientific knowledge. Publication and presentation have been separate but could “morph” into a single entity. This metamorphosis is taking place and is driven by a juggernaut called PowerPoint, Microsoft's graphics and slide presentation software.

Power of PowerPoint

Over 95% of presentations use PowerPoint.7 It is the lingua franca of science. Each day 30 million PowerPoint presentations are produced. PowerPoint is on 250 million computers worldwide.7 There are four million PowerPoint lectures on the web, and the number is increasing logarithmically (Google search). Reasons for the rapid spread are obvious. PowerPoint is easy, relatively inexpensive, and fast, and scientists control production.

As with metamorphoses in nature, this metamorphosis is occurring in discrete stages.

Stage 1: “journal speak” to PowerPoint

Scientists share findings and ideas. For 300 years the language of communication has been the paper journal.8 We could not find any randomised trials that compared learning and comprehension from journal articles with that from PowerPoint. Research in cognitive psychology has shown that we remember iconic images better than text.2 We learn the language of scientific articles late, as graduate students in our mid-20s. Writing “journal speak” is difficult, with abbreviations and strange sentence structures. Each discipline has its own almost incomprehensible journal dialect. To become literate in “journal speak” takes years. In addition, for people whose primary language is not English, article writing is onerous. Articles may be rejected because of “bad” grammar, not bad science. Contrast this with PowerPoint: children can learn it in kindergarten, it is so easy.7

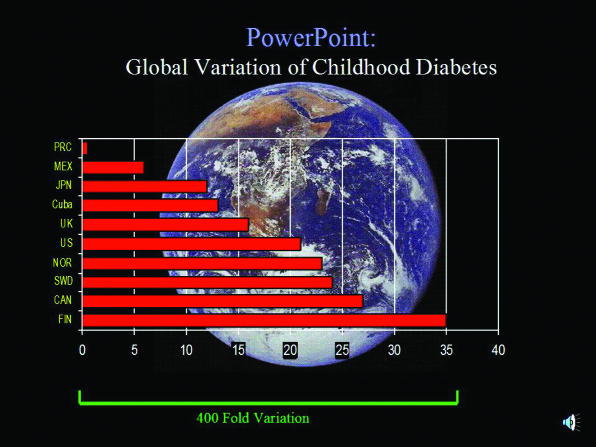

Journal Jargon Language (JJL)

The proposed research was designed to test the hypothesis that there is significant global variation in type 1 diabetes. The research used the protocol of the WHO DiaMond Project. The incidence density analyses revealed evidence of country differences. Individuals <15 years of age in Finland had a RR of 930 of diabetes than children in China. The 95% CI were 382-402. The AR for country was 91.2%. Age-period-cohort analysis using Poison regression revealed significant differences across countries.

PowerPoint's rules of grammar are more logical and abbreviated than the stilted language of the “article” summarised in the box. Moreover, with lectures in astrophysics or meteorology even a person trained in paediatrics could gain some knowledge; not so from scientific papers. Fewer people will “flunk” out of science because they cannot “journal speak.”

Stage 2: P 2 P ⇒ P 2 J 2 P ⇒ P 2 P

Our primary goal is to exchange findings with other scientists. Before journals were created, scientific exchange was by letter. In modern information technology (IT) this is P 2 P (peer to peer). As journals moved into the “modern” era P 2 J 2 P evolved, person to journal to person. Journals shape communication, with a standard format (IMRAD), traditional peer review, and distribution channels. We have unquestionably accepted this for 300 years. However, we can find few scientific data that support this. Most certainly the journal systems works, but is it optimal? There is no cost of P 2 J, as we freely give away our copyright. The J 2 P costs, however, are enormous. With PowerPoint and the internet the “journal” middleman can be eliminated and we can return to P 2 P. This may be a much leaner, and efficient, system. Once again, it would be simple to scientifically compare P 2 P with P 2 J 2 P.

In recent years programs such as Napster have become widely used (www.napster.com), but not in science to any degree. Napster was a P 2 P system for sharing MP3 music files. Sharing PowerPoint .ppt files is as easy as sharing MP3 files. Soon we scientists can be interwoven and directly share .ppt files for free.

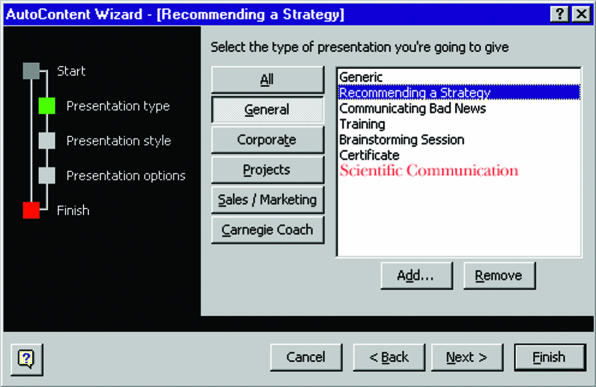

Stage 3: IMRAD to Autocontent Wizard

The Autocontent system provides a template for communications such as “training” or “communicating bad news.”6 What if there was a template for “scientific communication”? This would give a backbone organisation for research communication and might be considerably better than the ancient IMRAD system.

Stage 4: Traditional peer review to QC

Traditional peer review has been the Holy Grail, but with little science backing its adequacy. What is the evidence that traditional peer review is the best form of quality control? In 300 years there has been almost no evaluation of other forms of quality control (QC) or comparisons of traditional peer review with other systems. One called Statistical Quality Control, used by Toyota and manufacturing, was established by Deming.9 It is used in our Supercourse (www.pitt.edu/∼super1/). It is a post-review process in which an evaluation form appears at the end of PowerPoint lectures. Most certainly any research communication system needs effective quality control, but need it be the traditional approach? It is essential to establish evidence based Kaizen (continuous improvement over time). There is a wonderful science of quality control, and new approaches, including 6 Sigma10 and www.Slashdot.com, are made possible with the web. These have not been contrasted with the traditional approaches, but need to be. Instead of arguing, let's put the different approaches to quality control to direct head to head competition.

Stage 5: From $$$$$$$$$$$$ to $

If you invested $1000 in Elsevier Press in 1970, you would now be wealthy. Many believe that journals are destitute and exist only to help science, but in fact upper tier journals have profit ratios that are in the ranges achieved by pharmaceutical companies. We pay to create our papers and then give them away for free to million dollar industries.3 In contrast, engineers obtaining patents, artists painting pictures, authors writing books, and musicians writing music do not give away their intellectual property. By eliminating the middleman, we can substantially reduce costs and make health information more equitable.

Stage 6: Reach the unreached

Populations with special needs have not been served well by the journal system. Few studies are accessible to people with visual impairment. Inexpensive “voiced” PowerPoint presentations with large type currently bring access. PowerPoint is a disability- friendly technology; the journal article is quite the opposite.

Stage 7: Research toooooooooooooooooo classroom: research-classroom

In college textbooks the newest scientific journal references are 3-4 years old. Research findings take years to diffuse into classrooms. However, if the research communications were in the presentation mode of PowerPoint, diffusion could take minutes rather than years.11

Overall comparison

There's no contest (see table).

We are not Microsoft sales people, we are scientists. We receive no money from Microsoft. We do not even like the approaches of Microsoft.

PowerPoint dominates presentations. Could PowerPoint dominate all research communication? Yes. Would it be good for science? We don't know, but we must be prepared, should it happen. We need to establish an evidenced based system to continuously evaluate the new approaches to research communication.

The current metamorphosis has two facets: one is the medium “PowerPoint” that is creating new structure to capture information; the second is the “IT infrastructure” that captures, processes, stores, filters, and distributes the information. This combination of PowerPoint and IT is creating the conditions for people to manage knowledge in a completely new way. The value added is not to “repeat” information but to create “meaning.” From a “high tech/high touch” perspective, PowerPoint/IT is offering us the opportunity to develop further and evolve our thinking capabilities.

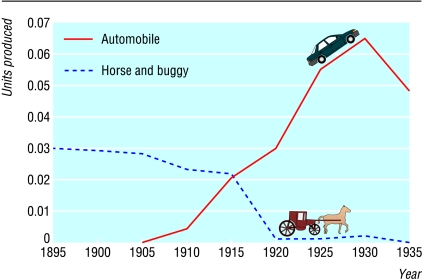

There are parallels in the adaptation of technology. The birth of the automobile brought the billion dollar horse and carriage industry to its knees in five years.12 Similarly, CDs ousted records from circulation.13

Few 300 year old technologies are still operating in science. A major problem has been the surprising lack of scientific evaluation by scientists. This needs to change. It is time for evidenced based scientific communications.

“From a certain point onward there is no longer any turning back. That is the point that must be reached.”

Kafka

Figure.

Diffusion of technology

Table.

Journals versus PowerPoint

| PowerPoint

|

Traditional journal

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Cost | None* | Expensive |

| Production | P 2 P | P 2 J 2 P |

| Format | Multiple | IMRAD |

| Ease of production | Easy | Difficult |

| Timeliness | Just in time | 12 months |

| Global access | High | Low |

| Scientist control | Production, review, distribution | Production |

| Special population access | Easily done | Rare |

| Peer review | Scientific based, high throughput, accurate, cheap | Little backing evidence, long tradition, accuracy unknown |

| Research to classroom | Minutes | Years |

After initial cost.

Acknowledgments

We are comparing this article with a PowerPoint presentation. Please go to www.pitt.edu/∼super1/lecture/lec8301/index.htm and indicate your preference.

Footnotes

Funding: The Global Health Network is supported by funds from the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.LaPorte RE, Marler E, Akazawa S, Sauer F, Gamboa C, Shenton C, et al. The death of biomedical journals. BMJ. 1995;310:1387–1390. doi: 10.1136/bmj.310.6991.1387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Global Health Network Group. The reincarnation of biomedical journals as hypertext comic books. Nature Medicine 1998:4. www.nature.com/nm/web_specials/comics/ (accessed 11 Dec 2002).

- 3.LaPorte RE, Hibbits B. Rights, wrongs, and journals in the age of cyberspace. BMJ. 1996;313:1609. doi: 10.1136/bmj.313.7072.1609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Delamothe T, Smith R. Moving beyond journals: the future arrives with a crash. BMJ. 1999;318:1637–1639. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7199.1637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldbeck-Wood S. Evidence on peer review—scientific quality control or smokescreen? BMJ. 1999;318:44–45. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7175.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Varmus H. E-Biomed: a proposal for electronic publication in the biomedical sciences. www.nih.gov/about/director/ebiomed/ebi.htm#A proposal for E-biomed (accessed 4 Dec 2002).

- 7. Parker R. Absolute Powerpoint. New Yorker 20 May 2001;76-87.

- 8. Harmon JE, Gross AG. 2002. The scientific article, from the republic of letters to the world wide web. www.lib.uchicago.edu/e/spcl/webex/sciart/home.html (accessed 4 Dec 2002).

- 9.Grant EL, Leavenworth RS. Statistical quality control. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 10. What is 6 Sigma. www.whatis.com/definition/0,,sid9_gci763122,00.html (accessed 4 Dec 2002).

- 11.LaPorte RE, Sekikawa A, Sa ER, Linkov F, Lovalekar M. Whisking research into the classroom. BMJ. 2002;324:99. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7329.99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hess KL. The growth of automobile technology. 1996. www.klhess.com/car_essy.html www.klhess.com/car_essy.html (accessed 4 Dec 2002). (accessed 4 Dec 2002). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rogers EM. Diffusion of innovations. 4th ed. New York: Free Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]