A sugar planter's son from Barbados who graduated at Edinburgh was one of the first people to experiment with transfusing blood, in the early 19th century, nearly 100 years before the discovery of blood groups made transfusion routinely practicable

James Blundell of London is credited with introducing blood transfusion into the practice of medicine. It was his extensive research in animals and his well disseminated writings that established transfusion as a treatment in the first quarter of the 19th century.1 Blundell acknowledged two colleagues as the inspiration for his work, both from the island of Barbados: Leacock and Goodridge, of whom the more important was John Henry Leacock.

The concept of transfusion therapy had been set aside for 150 years after the failures of transfusion of animal blood into humans by Denys in Paris and Lower in London in the 17th century. Sporadic, haphazard trials with animal blood, including one by Blundell's uncle, a Dr Haighton,1 were known, but it remained for Leacock to do the first set of planned experiments in 1816 that established the need for species compatibility. Blundell reopened the subject a year later, and after that trials of human blood transfusion were made throughout the world.2 Many were successful, despite the fact that it was not until almost 100 years later that discovery of the blood groups made it possible to predict compatibility of donor and recipient.

Summary points

Early attempts to transfuse humans with animal blood were made in the 17th century and sporadically thereafter up to the 19th century

In 1816 John Henry Leacock, from Barbados, reported systematic experiments in Edinburgh on dogs and cats that established that donor and recipient must be of the same species, and recommended inter-human transfusion; he then returned to Barbados and published nothing more

James Blundell, who extended Leacock's experiments and publicised the results widely, is credited by many with introducing transfusion into clinical use but himself always gave credit to Leacock for his initial work

First reports

Leacock graduated in medicine at Edinburgh in 1817, four years after Blundell. He defended his dissertation, On the Transfusion of Blood in Extreme Cases of Haemorrhage, in 1816. He advocated the transfusion of human blood as treatment for haemorrhage, but also for “deficiency of blood.”3 He asked if the then universal practice of bloodletting was therapeutic: “What is there repugnant to the idea of trying to cure diseases arising from an opposite cause by an opposite remedy, to wit, by transfusion?” He performed animal experiments that proved that donor and recipient must be of the same species. Unlike Blundell, who published and republished his experiments, Leacock made only the one report, and he left no record of any human transfusion experiments.

Blundell's Edinburgh dissertation had been on a study of hearing and music. On 3 February 1818 his first proposal on transfusion, from Guy's Hospital, was communicated to the Medical and Chirurgical Society of London by Mr Henry Cline.4 Blundell had been requested to see a woman dying of uterine haemorrhage. He speculated that she very probably could have been saved by transfusion. For that idea, he credited Leacock's work of “a few months earlier,” which he said gave him his “first notions on the subject.” Blundell first reported his animal experiments and then in October of the same year he reported to the society that he had given a transfusion of human blood to a patient “with temporary success.”1

John Henry Leacock

John Henry Leacock is an ancestor of one of the authors, who himself worked with the British Blood Transfusion Service in Luton in 1942. The family, from Hampshire, was among the early settlers in Barbados, arriving there in 1635. In the 18th century, many fortunes were made from sugar and almost as many lost, but John Henry could be sent to Edinburgh to qualify in medicine. He returned to the family estates, and there is no information as to whether subsequently he ever practised. There is a record by a visiting Sir Henry Fitzherbert that Leacock played the pleasant host to him at the family estate, Renewal, in 1825. They went together to see a school for slaves operating in the parish church at St Lucy. Leacock made his will on 17 July 1826 on a voyage back to England, where he died in 1828. He left his Barbados estate to his mother and to his son, another John Henry. That son placed a memorial in the churchyard of St Lucy parish to his mother, Jane A Leacock, who died in 1842. The inscription on the stone, barely visible today, recognises her as the widow of Dr John H Leacock.

The critical animal experiments

In his experimental transfusions in Edinburgh Leacock used dogs and cats as recipients and dogs and sheep as donors. He reported on eight trials in which he bled the recipient animals and then attempted to revive them by transfusion through an ox ureter with crow's quills attached to the ends.3 Three dogs were successfully given canine blood. A cat survived the use of canine blood, but when lamb's blood was given to three different dogs, only one survived. Leacock wrote that blood from an “animal of the same species is sufficient to support life” but blood from an animal of a different species “appears not to answer the purpose.”

In several other experiments, Leacock created a cross circulation between two dogs, modifying the rate of flow and observing the effects of impeding and re-establishing the dual circulation. In another experiment, he intentionally overtransfused a cat with canine blood, with resultant “plethora,” which was at the time thought to be due to “an overabundant supply of chyle.” He proved his point that the problem was blood and not lymph by dissecting out the vessels, which were “gorged with black blood.” In a footnote to Leacock's published dissertation, the journal editor wrote of that observation: “This experiment is worth ten thousand pounds! . . . [it] ought to be printed in letters of gold, and impressed on the minds of every individual in the profession.”3

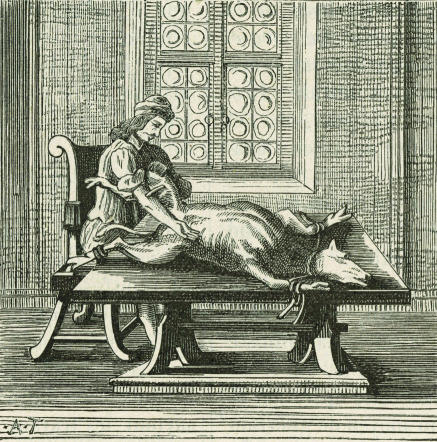

Blundell became aware of Leacock's work and then made an orderly study of transfusion in London. In four experiments, he was able to revive dogs that he had bled to “apparent death,” by the transfusion of canine blood. He succeeded also with autologous transfusions. After that, noting Leacock's lack of success with lamb's blood, he used human blood in an attempt to revive exsanguinated dogs. Four dogs died, one lived a few days, and one recovered. Blundell also performed experiments on the length of time that it took for blood to coagulate in his transfusion method, which used a receiving cup and a syringe. He contrasted his experiments with those of Leacock as differing in three ways: he transfused venous blood, not arterial; he used human blood in dogs because of Leacock's failure with lamb's blood; and he used an indirect transfer of blood by syringe as opposed to Leacock's direct method of connecting donor and recipient.4 Blundell did note that human blood had been used successfully in a dog in London at about that time by another worker from Barbados, a Mr Goodridge, who was not identified further, but pointed out that his own experiments gained “additional strength, when associated with others instituted by Dr. Leacock (also of Barbadoes).”

Blundell had a career as a famous practitioner and teacher of obstetrics. His lecture notes were published in the Lancet and were distributed widely in the western world in several text forms, all giving information on the value of transfusion. In the preface to one of these publications, the editor, Thomas Castle, wrote that the section headed “Transfusion” had been specifically rewritten for that edition by Blundell.5 In that section, Blundell again credited Leacock, whom he identified as “one of my own respected and esteemed pupils.” Blundell clearly considered that his work was an extension of that of the now forgotten Leacock.

The Edinburgh connection

Edinburgh at that time was ideal for students from the New World. An education there was cheap; there were no religious restrictions; and the lectures were in English.6 An earlier graduate, Philip Syng Physick of Philadelphia, who later studied with John Hunter, has been credited with using human blood for transfusion as early as 1795.2 Another student of medicine at Edinburgh was William Thornton, who was from Tortola and is better remembered as the architect of the Capitol building in Washington, DC. Recent publication of his papers has revealed that in 1799 Thornton proposed to revive George Washington with lamb's blood.7 That was after the President had been declared dead by two doctors who had bled America's first great citizen of almost two and a half litres of blood while treating him for his obstructive epiglottitis. Thornton's proposal for a resurrection by transfusion was, however, declined by the family.

The ideas and actions of at least these four doctors—Physick, Thornton, Leacock, and Blundell—followed from their education at Edinburgh. It may be that there was a continuing interest at that school in the transfusions that had been done in the middle of the 17th century, an interest that led students who were at Edinburgh over a 30 year span to introduce blood transfusion into acceptable clinical practice. Intriguingly, Leacock said in his report that it was likely that the use of transfusion to “excite” the heart of a human subject “is confirmed by my own experiments, and those of others.”3 He did not identify the others.

The forgotten Dr Leacock

There is no question that Blundell introduced blood transfusion into the medical armamentarium of the 19th century. He publicised the procedure throughout the world in his influential writings on obstetrics. Leacock was but a minor figure and has been all but forgotten, but he sparked the 19th century's fascination with transfusion. Unlike the chroniclers of Blundell's successes, that author did not neglect to acknowledge that the “first notions” for use of transfusion came from the work of John Henry Leacock of Barbados.

Figure.

MEPL

Human blood was used in an attempt to revive exsanguinated dogs

Footnotes

Competing interests: PJS is the historian of the International Society of Blood Transfusion; AGL, besides working for the Blood Transfusion Service in Britain in 1942, later set up the Barbados blood bank.

Funding: None.

References

- 1.Blundell J. Researches, physiological and pathological. London: E Cox and Son; 1825. Some remarks on the operation of transfusion; pp. 63–146. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schmidt PJ. Transfusion in America in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. N Engl J Med. 1968;279:1319–1320. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196812122792406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leacock JH. On transfusion of blood in extreme cases of haemorrhage. Med Chir J Rev. 1817;3:276–284. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blundell J. Experiments on the transfusion of blood by the syringe. Med Chir Transact. 1818;9:56–92. doi: 10.1177/09595287180090p107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Castle T, editor. The principles and practice of obstetricy as at present taught by James Blundell, M.D. Washington, DC: Duff Green; 1834. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Porter R. The greatest benefit to mankind: a medical history of humanity. New York: Norton; 1998. p. 291. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schmidt PJ. Transfuse George Washington! Transfusion. 2002;42:275–277. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.2002.00033.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]