A half century has passed since Stalin accused a group of doctors—most of them Jewish—of plotting against the state. The ramifications of this case continue to the present day

Just under 50 years ago, on 4 April 1953, Pravda carried a prominent statement by Lavrenty Beria, Stalin's infamous head of secret police, exonerating nine Soviet doctors (seven of them Jews) who had previously been accused of “wrecking, espionage and terrorist activities against the active leaders of the Soviet Government.” The Soviet people, especially its Jews, were astounded to learn that just a month after Stalin's death the new leadership now admitted that the charges had been entirely invented by Stalin and his followers. Seven of the doctors were immediately released—two had already died at the hands of their jailers.

The infamous “Doctors' Plot” speaks volumes about Soviet politics, Stalin's role, the persistence of a medieval view of doctors as potential poisoners, and the survival of overt anti-Semitism in the Soviet Union, despite the known horrors of the recent Holocaust.1,2 For Stalin, whose deeds easily matched those of Hitler and whose deceits had been evident throughout his life, the Doctors' Plot and intended show trial were meant to cleanse the Soviet Union of “foreign,” “cosmopolitan,” and “Zionist” (read Jewish) elements. In fact, it was the only one of Stalin's show trials that did not come off—only because he died just before the spectacle was to begin.3

Summary points

Stalin used show trials—as well as mass murder and forced migration—to terrify and silence citizens of the Soviet Union

In early 1953 Stalin planned to stage a show trial of several doctors, most of whom were Jewish and who were falsely accused of acting against the state—a trial that underlined Stalin's anti-Semitism

Despite the state's exoneration of the doctors immediately after Stalin's death, persistent anti-Semitism in the Soviet Union contributed to the emigration of hundreds of thousands of Jews, including many doctors, in subsequent decades

Stalin's plans

On 13 January 1953 the Soviet government declared in Pravda that nine of the Kremlin's most prestigious doctors had, several years earlier, murdered two of Stalin's closest aides.4 (An English translation of the article has recently been posted on the internet.5) Moreover, as Rapoport relates, these practitioners were accused of taking part in a “vast plot conducted by Western imperialists and Zionists to kill the top Soviet political and military leadership . . . [Until Stalin's death] the Soviet media pounded away at the supposed single ‘fifth column’ in the USSR, with constant references to Jews who were being arrested, dismissed from their jobs, or executed.”6

The show trial was meant to initiate a carefully constructed plan in which almost all of the Soviet Union's two million Jews, nearly all of whom were survivors of the Holocaust, were to be transported to the Gulag—in cattle cars. Between the January announcement and Stalin's death a month and a half later it became clear that careful plans had been laid for the transfer and “concentration” of Soviet Jews. Rapoport quotes a Soviet Jewish engineer who reported seeing, in the early 1960s, a “never used camp with row after row of barracks: ‘Its vastness took my breath away.’ ”6 Other witnesses corroborated the existence of the deportation plans.

Anti-Semitism and mistrust of doctors

Stalin's hatred of Jews and of Jewish doctors in particular did not appear in a vacuum. European anti-Semitism had long manifested, as one of its more bizarre subtypes, a fear (and respect) for Jewish doctors. This recurrent delusion is typified by a statement from the Catholic Council of Valladolid in 1322: Jewish physicians “under guise of medicine, surgery, or apothecary commit treachery with much ardor and kill Christian folk when administering medicine to them.”2

Stalin had long manifested his hatred not only of Jews but, by extension, of Jewish nationalism (Zionism). Though using somewhat derivative terminology, his slander of both was expressed in the same spirit as the omnipresent anti-Semitism of the Tsarist period in which Stalin grew up. At that time the notorious Tsarist police forgery The Protocols of the Elders of Zion was widely circulated in Russia and beyond.7 This tract claimed that world Jewry aspired to international domination through control of the world's banking system and through socialist subversion. Despite the fact that in 1921 the forgery was exposed in the Times of London, it survives today, mainly but not exclusively in the Arab world, where an ongoing television series is based on the Protocols.8

Sometimes Stalin's concerns conflicted. For example, when Lena Shtern, a well known Jewish scientist, was tried secretly on trumped up charges in 1952, Stalin spared her life, imprisoning her for “only” five years—probably because she was the Soviet Union's foremost expert on longevity, a field that intrigued the ageing leader.6

In general Stalin severely mistrusted doctors—whatever their nationality. In his memoirs Dmitri Shostakovich tells the tale of Vladimir Bekhterev, a world renowned psychiatrist who at 70 was summoned to assess Stalin's mental condition.9 The good doctor described him as ill, perhaps even paranoid. And how right he was. Bekhterev died immediately afterwards—poisoned by Stalin.

But Stalin's special hatred was reserved for Jewish doctors. Although in the last decades of Tsarist rule Jews were restricted from owning land and excluded from most other professions, they had indeed entered medicine in numbers far out of proportion to their small percentage in the overall population.6 So when Stalin decided to resolve the Soviet Union's “Jewish problem,” it made perfect sense to open the campaign with a show trial against a group of (mainly Jewish) doctors who were often branded “Zionists” or agents of the “Joint” (an international Jewish charitable organisation).

A propaganda offensive accompanied the plans to deport—“for their own good”—the Jewish population. One million copies of a pamphlet were prepared for distribution—its title: “Why Jews Must Be Resettled from the Industrial Regions of the Country.” The deportation was purportedly “in response” to a carefully orchestrated letter prepared for Pravda and signed by many terrified Soviet Jewish leaders, imploring “The Father of all the Peoples” to deport the Jews for their own protection. It appealed to “the government of the USSR, and to Comrade Stalin personally, to save the Jewish population from possible violence in the wake of the revelations about the doctor-poisoners . . . of Jewish origin . . . We, as leading figures among loyal Soviet Jewry, totally reject American and Zionist propaganda claiming that there is anti-Semitism in the Soviet Union.”6

According to Stalin's plan, the doctors would be convicted and scheduled to be hanged—symbolically—around Easter. As Rapoport explained:

Then “incidents” would follow: attacks on Jews orchestrated by the secret police, the publication of the statement by the prominent Jews, and a flood of other letters demanding that action be taken. A three-stage program of genocide would be followed. First, almost all Soviet Jews . . . would be shipped to camps east of the Urals . . . Second, the authorities would set Jewish leaders at all levels against one another . . . Also the MGB [Secret Police] would start killing the elites in the camps, just as they had killed the Yiddish writers . . . the previous year. The . . . final stage would be to “get rid of the rest.”6

Contemporary responses

Of interest is the approach taken at the time by the two main organs of British medicine, the British Medical Journal and the Lancet. The Lancet made no mention of the plot. The British Medical Journal did publish an interesting leader article exactly one week after the dramatic announcement in Pravda in April exonerating the doctors.10 Entitled “The accused Russian doctors,” it referred to a wishy-washy pronouncement from the World Medical Association.11 The journal, perhaps a bit wiser (and braver) after the Soviet recantation, admitted that “As doctors we felt disturbed by the assault upon the professional integrity of our Russian colleagues and especially by the probable effect of the accusation on the trust patients universally have in the doctor-patient relationship.”

The only other English language reference that I could locate was a letter to the editor of the Journal of the American Medical Association in March, submitted by the Israel Medical Association, stating forthrightly that “a false charge has been leveled against the accused physicians and that the trial against them is staged for certain political ends.”12

No statement appeared in the British medical press between the Pravda announcement of the Doctors' Plot in January and the retraction in April. Furthermore, I could find no other mention of this case in any section of these three journals after 11 April 1953.

Emigration of the Jews

Although the immediate de-Stalinisation that followed the dictator's death made life less fearful for all of the Soviet Union's peoples, the country's Jews were not yet out of the woods. The next four decades saw periods of resurgence and quiescence in Soviet anti-Semitism. During the Brezhnev years an unusual combination of state inspired anti-Semitism and a relaxation of the emigration regulations facilitated the exit of approximately 200 000 Jews, many of whom went to Israel. Later, with glasnost and perestroika, almost one million more Jews left, most once again to Israel. A large number of these migrants were doctors, their move strongly enriching Israel's medical profession.13

In the end, Stalin's plot failed for one reason only: he died before completing the mission. The final irony is that over the past two decades the cream of Soviet Jewish medicine has gone from being vilified in their land of birth to free practitioners of their craft in the Jewish state. Stalin, one hopes, is indeed rolling over in his grave.

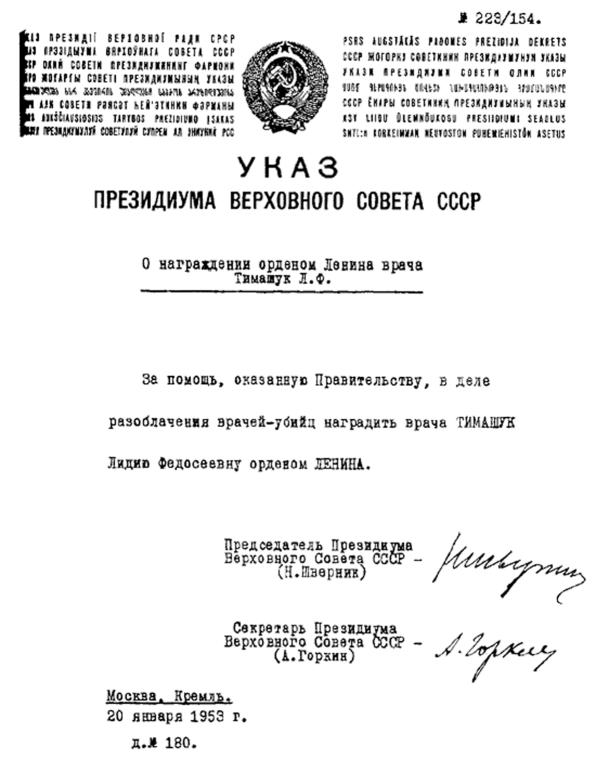

Figure.

Decree of the Supreme Soviet of 20 January 1953 awarding the Lenin Order to Dr Olga Timashuk for help in “exposing the physician-murderers. On 3 April 1953 the award was cancelled “in view of the true circumstances coming to light”

Figure.

“Evidence of a crime,” cartoon from the January 1953 edition of Krokodil. This edition attacked Western bankers, Nazi generals, the Vatican, and the “Zionist conspiracy”

Footnotes

Funding: None.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Amis M. Koba the Dread: laughter and the twenty million. New York: Miramax; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heynick F. Jews and medicine: an epic saga. Hoboken, NJ: KTAV; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ulam A. Stalin, the man and his era. New York: Viking; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 4. [“Vicious spies and killers under the mask of academic physicians.”] Pravda 1953 Jan 13:1. (In Russian.)

- 5. Cunningham HS. Article in “Pravda” about the “Doctors' Plot.” www.cyberussr.com/rus/vrach-ubijca-e.html (accessed 2 Dec 2002). [Translated by P Wolfe.]

- 6.Rapoport L. Stalin's war against the Jews: the Doctors' Plot and the Soviet solution. Toronto: Free Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cohn N. Warrant for genocide. London: Penguin Books; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Shapiro H. Egyptian TV to air ‘Protocols’ show despite promise to shelve it. Jerusalem Post 2002 Oct 25:5A.

- 9.Volkov S, editor. Testimony: the memoirs of Shostakovich. New York: Harper Colophon; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 10.The accused Russian doctors [editorial] BMJ. 1953;i:824. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Medical Association. “Charges against Russian doctors.”. BMJ. 1953;i(suppl):136S. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abeles W, Avigdori Z, Avramovitz A, Adler A, Adler S, Alutin A, et al. “Statement from Central Committee of Medical Association of Israel” [letter] JAMA. 1953;151:939. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nirel N, Rosen B, Gross R, Berg A, Yuval D, Ivankovsky M. “Immigrants from the former Soviet Union in the health system: selected findings from a national survey.”. Bitachon Soziali. 1998;51:96–116. [Google Scholar]