Was Gustav Klimt the Damien Hirst of his time? The response that greeted some of his paintings certainly made for instant notoriety

In 1893 Austria's ministry of culture commissioned the artists Gustav Klimt and Franz Matsch to decorate the Great Hall of the University of Vienna.1 The Habsburg empire had entered its final phase, and Vienna, one of Europe's flourishing cultural and scientific centres, was under liberal rule and experiencing a period of industrial expansion and new ideas that was to become known as the Ringstrasse era.1 Ringstrasse, an imposing avenue, encircled the old centre of Vienna, and grand buildings were erected along it.1

Summary points

In 1893 Gustav Klimt was commissioned to decorate the University of Vienna with The Triumph of Light over Darkness, a series of paintings representing the university's faculties

Medicine was presented in 1901, scandalously focusing on the powerlessness of the art of healing and ignoring achievements in prevention and cure, at a time when Vienna was leading the world in medicine

The paintings were never fixed to the ceiling of the university's great hall, and in 1943 they were moved for protection to a castle, which was destroyed. All that remains from Medicine are drafts and photographs

Klimt died in 1918 during the influenza pandemic

The artist

Gustav Klimt was the second of seven children born to a family of gold engravers who had immigrated to Vienna from Bohemia. In 1876, at the age of 14, he was admitted with distinction to the Kunstgewerbeschule, the public school of arts and crafts. Gustav, his younger brother Ernst, and their friend Franz Matsch were held in high regard by their teachers, who often recommended them for paid work outside the school.2 The three young artists were soon involved in the ambitious Ringstrasse project, decorating the grand stairway of the new Burgtheater from 1888 to 1890. In 1891, after decorating the great lobby of the Kunsthistorisches Hofmuseum (the museum of art history), they were awarded a major state prize.3 These first works, although created in a conventional style and lacking originality and inspiration, heralded Klimt's versatile talent. The commission for the paintings of the university faculty seems something of a logical consequence.

Painting the ceiling of the Great Hall of Vienna University

The theme of the ceiling of the university's Great Hall was the triumph of light over darkness. It consisted of a central panel encircled by four paintings representing the university faculties. The concept was quite conventional, similar to others executed for public buildings throughout Europe. Klimt undertook Philosophy, Medicine, and Jurisprudence, and Franz Matsch undertook Theology and the central panel.3

Meanwhile, Klimt's artistic views had started to change in a climate of reform that had spread after the country's financial crisis of 1873.1 In 1897 he founded the Secession movement, leading a group of young artists out of the established artists' association.1–3 The quotation from the German writer Friedrich Schiller that was included in Klimt's 1899 painting Nuda Veritas—“If you cannot please everyone with your deeds and your art, please a few”—announced that pleasing his clients was not his priority any more.3 He started to seem distant and produced little work. His beloved brother Ernst had developed pericarditis secondary to a heavy cold and died in 1892; their father had died a few months before. The ministry of education refused to ratify Klimt's election to the chair of the history of painting at the Academy of Fine Arts.3 Although Klimt had received advance payments and the liberal minister of education, Baron Wilhelm von Hartel, was enthusiastically supportive, detailed studies of the commissioned paintings were not ready until 1898.

In 1900, the year in which Sigmund Freud published The Interpretations of Dreams,4 Klimt exhibited a preliminary version of Philosophy. The members of the university and the public had expected a masterpiece in the manner of Raphael's School of Athens. One of the professors had suggested a scene with the philosophers of the ages shown together, talking and teaching.5 Instead, viewers were confronted with a towering column of naked embracing figures set against a background of limitless space from which the sleepy head of a sphinx emerged.2,3 The single sign of the conscious mind was a bright female head, Wissen [knowledge], at the bottom of the picture.6 Ignoring Klimt's virtuoso use of colour and composition, the academics accused him of presenting unclear ideas through unclear forms,6 a controversy that lasted for months.1,3

The conception of medicine: doctors versus the artist

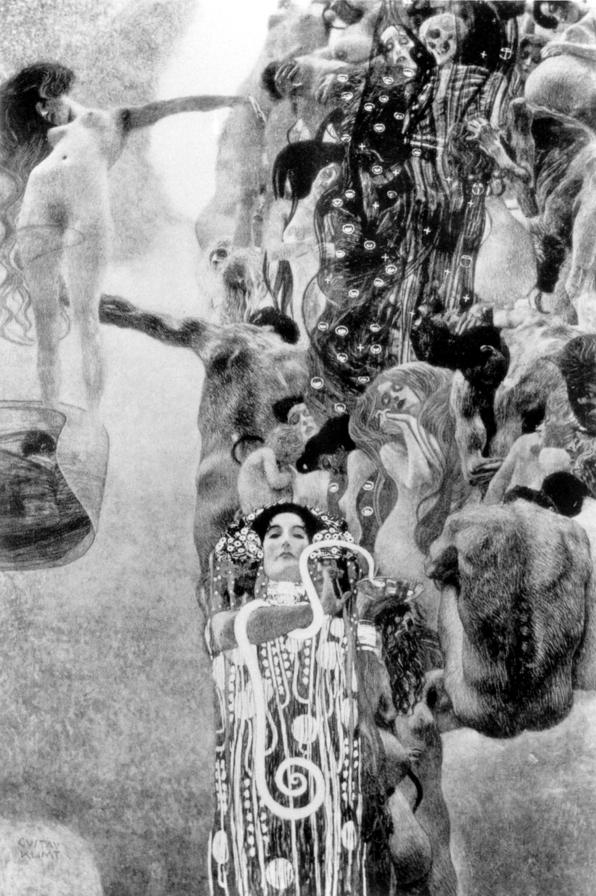

Despite the attacks, Klimt presented Medicine (figure) at the 10th exhibition of the Secession group in 1901. Medicine resembled Philosophy, with a column of naked figures beside which a nude young female, representing Life, floated in space, with a newborn infant in front of her feet.7 Death was represented as a skeleton placed centrally, in the river of life, which was formed by the human bodies.1 At the bottom of the picture the dominating figure of Hygieia (see cover) confronted the spectator with the Aesculapian snake around her arm, holding the cup of Lethe [oblivion].1 The only links between the drifting bodies and Life were provided by Life's extended arm and the arm of a male nude shown from the back. It was obvious that the painter wanted to emphasise the powerlessness of the healing arts and made no attempt to represent the triumph of medicine in the way that doctors would expect.3 An editorial in the Medizinische Wochenschrift complained that the painter had ignored doctors' two main achievements, prevention and cure.1,8 At a time when Vienna was leading the world in medical research thanks to the pioneering work of doctors such as Theodor Billroth (1829-94), Frantisek Chvostek (1835-84), and Ludwig Türck (1810-68),9,10 Klimt presented medicine's field as “a fantasmagoria of half dreaming humanity, sunk in instinctual semisurrender, passive in the flow of fate.”1

Art critics attacked Klimt's work, saying that the project was beyond his intellectual level.3 Vienna's most trenchant journalist, Karl Krauss, scornfully described Medicine as a painting in which the chaotic confusion of decrepit bodies symbolises the situation in a state hospital.11 Accusations of pornography were also raised; the public prosecutor was called in, and, although he did not proceed to action, the issue reached parliament1—the first time that a cultural debate had ever been raised there. The education minister again defended Klimt's work, but when Klimt was once again elected to a professorship at the Academy in 1901, the government refused to ratify the election. He was never offered a teaching post anywhere again.3

The artist's defence

Klimt's contemporary defenders presented him as a misunderstood, lonely artist who was persecuted for his rebellious art, a popular stereotype in the 19th century.8,11 But Klimt was not a rebel.11 He rose to fame in the service of Viennese society and enjoyed recognition and support from the state. Art historians additionally claimed that Klimt was persecuted for his erotic convictions, although he had led a rather discreet life, unlike most of his famous contemporaries in fin-de-siècle Vienna.2

Klimt was not ignorant in aesthetic and philosophical matters. His Philosophy indicates an inspiration provided by the ideas of composer Richard Wagner and philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche,1,12 and Hygieia reveals awareness of the symbolic world of mythology. He had witnessed the deaths of his father and brother, and he had seen his younger sister dying at the age of 5 and his eldest sister and mother gradually losing their sanity. Gustav Klimt and Sigmund Freud shared the same city and cultural milieu. A “crisis of liberal ego” has been proposed, comparing the artist's intentions to the psychoanalyst's approach.1 Both went through a personal crisis, reforming their work and having to face rejection when they exhibited the results of their explorations in the chaotic world of instinct.

A fatal outcome

Jurisprudence was exhibited in 1903 and, sharing the same symbolism as Medicine and Philosophy, was attacked in the same forceful manner.11 Meanwhile Matsch had completed his own paintings, different from Klimt's in both style and concept. The ministry of education's advisory committee advised that the whole composition should not be fixed to the ceiling but be permanently exhibited in the new state gallery of modern art. The paintings were requested for an international exhibition in St Louis, United States, in 1904, but the ministry declined, anxious of the reaction of a foreign public.3 Klimt resigned the commission, declaring that he wished to keep his work. The ministry insisted that the paintings were already the property of the state but had to succumb when Klimt threatened the removal staff with a shotgun.2 Klimt repaid his advance with the support of August Lederer, one of his major patrons, who in return received Philosophy. In 1911 Medicine and Jurisprudence were bought by Klimt's friend and fellow artist, Koloman Moser.13

Both Klimt and Moser died in 1918 during the influenza pandemic.14 Medicine was bought by the Österreichische Galerie, and Jurisprudence passed into the hands of the Lederer family.3 As the Lederers were of Jewish origin their entire collection was “Aryanised” in 1938, and soon after, the three faculty paintings all found their place in the Österreichische Galerie.3 In 1943, after their last exhibition, they were moved for protection to Schloss Immendorf, a castle in Lower Austria, to the north of Vienna and just a few kilometres from today's Austrian-Czech border.2,3 In May 1945 the paintings were destroyed as retreating German SS forces set fire to the castle to prevent it falling into enemy hands.2,14 All that remains of the paintings are the preparatory sketches and photographs of poor quality. An oil composition draft from Medicine and a colour photo of Hygieia also exist. Matsch's Theology survives in the theology department of Vienna University.3

Klimt is now universally recognised as a pioneer of modern Viennese art, and the faculty paintings are regarded as a turning point in his brilliant career. Was the difficulty with the faculty paintings just a matter of place and time, and would any other academic institutions in other times behave differently to those in enlightened fin-de-siècle Vienna? In other words, would medical faculties now decorate their great halls with Gustav Klimt's Medicine?

Figure.

Gustav Klimt's painting Medicine (1901), which was destroyed in 1945. The photo was taken at the time and is the only surviving picture of the painting

Footnotes

Funding: None.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Schorske CE. Fin-de-siècle Vienna: culture and politics. New York: Vintage; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fliedl G. Gustav Klimt. Cologne: Benedikt Taschen Verlag; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Whitford F. Klimt. London: Thames and Hudson; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gay P. Freud: a life for our times. New York: W W Norton; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pirchan E. Gustav Klimt. Ein Künstler aus Wien. Vienna. 1956. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koschatzky W, Strobl A. Die Albertina in Wien. Salzburg: Residenz Verlag; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nebehay C. Gustav Klimt: Zeichnungen und Dokumentation (Katalog XV). Vienna. 1969. p. 240. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bahr H. Gegen Klimt. Vienna. 1903. . (In: Schorske CE. Fin-de-siècle Vienna: culture and politics. New York: Vintage, 1981:59.) [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wyklicky H. Prima inter pares. Internal medicine in Vienna at the beginning of the 20th century. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 1983;95:601–606. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rutledge RH. Theodor Billroth: a century later. Surgery. 1995;118:36–43. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6060(05)80007-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hofmann W. Gustav Klimt. New York: New York Graphic Society; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Vergo P. Gustav Klimts Philosophie und das Programm der Universitätgemälde. Mitteilungen der Österreichischen Galerie 1978/79;22/23:69-100.

- 13.Constantino M. Klimt. New York: Knickerbocker Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grist NR. Pandemic influenza 1918. BMJ. 1979;20:199. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.6205.1632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]