Abstract

Objective: To purify Mannan-binding lectin (MBL) from human serum and detect its binding ability to several kinds of bacteria common in infectious diseases of children. Methods: MBL was purified from human serum by affinity chromatography on mannan-Sepharose 4B column. Its binding ability to eight species, 97 strains of bacteria was detected by enzyme-linked lectin assay (ELLA). Results: MBL has different binding ability to bacteria and shows strong binding ability to Klebsiella ornithinolytica and Escherichia coli, but shows relatively lower binding ability to Staphylococcus haemolyticus, Enterobacter cloacae and Staphylococcus epidermidis. To different isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae and Staphylococcus aureus, MBL shows quite different binding ability. Conclusions: MBL has different binding ability to different bacteria, and has relatively stronger binding ability to Gram-negative bacteria. Its binding ability to different isolates of certain kinds of bacteria is quite different.

Keywords: Mannan-binding lectin (MBL), Children, Innate immunity, Bacteria

INTRODUCTION

MBL is a hepatic serum protein that belongs to the family of Ca2+ dependent collagenous lectins most of which are innate immune system components (Holmskov et al., 1994). MBL binds through multiple sites to various carbohydrate structures. Upon binding to its ligands, it can activate complement independently of antibody-C1Q using MBL-associated serine protease 1 (MASP-1) and MASP-2 (Jack et al., 2001; Turner and Hamvas, 2000).

Although MBL has the potential to express multiple biological effector functions, a prerequisite for all such activity is primary binding to multiple arrays of sugar ligands such as those on bacterial surfaces. To the author’s knowledge, there have been few studies of interactions between MBL and a variety of clinically important microorganisms. Herein we report such a study that uses ELLA to detect MBL binding abilities to various bacteria.

METHODS

Materials

CNBr activated Sepharose 4B was purchased from Pharmacia Company (USA). Mannan, Mannose and G1cNAc were purchased from Sigma Company (USA). Eight different species which included 97 strains of bacteria were isolated from both blood and sputum cultures. The bacteria included Klebsiella ornithinolytica (K. ornithinolytica) (n=11), K. pneumoniae (n=15), E. coli (n=13), Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) (n=13), S. haemolyticus (n=13). S. epidermidis (n=13), Enterobacter cloacae (n=10) and Haemophilus influenza (n=9) were all isolated from children with infection. The microbiology lab at Children’s Hospital, School of Medicine, Zhejiang University, prepared them. Human serum was purchased from the blood center of Zhejiang Province. Other reagents were donated by the Biochemistry and Molecular Biology Department, School of Medicine, Zhejiang University.

Extraction and purification serum MBL

(1) Preparation of affinity column

Three hundred mg of Mannan was coupled to 15 g CNBr-activated Sepharose 4B according to the Pharmacia manual instructions. This mixture was then poured into a column and equilibrated with TBS/Ca2+ binding buffer (0.01 mol/L Tris-HCl, 0.145 mol/L NaCl, 0.02 mol/L CaCl2, 0.002 mol/L NaN3, pH 7.4). The affinity matrix volume was about 50 ml.

(2) Purification of serum MBL

One thousand ml of human serum was precipitated on ice with 7% PEG6000 for 3 h. After centrifugation at 2000 g (4 °C) for 20 min, the precipitate was rinsed with 600 ml of 7.5% PEG6000 in cold (4 °C) TBS/Ca2+ binding buffer. After repeating the centrifugation, the precipitate was dissolved in 100 ml TBS/Ca2+. Following centrifugation at 12000 g (4 °C) for 10 min, the supernatant was collected and passed through the affinity column (50 ml manna-Sepharose 4B). The column was rinsed with TBS/Ca2+ binding buffer until A280 nm was below 0.005. The column was then eluted with TBS/EDTA eluting buffer (0.01 mol/L Tris-HCl, 0.145 mol/L NaCl, 0.01 mol/L EDTA, 0.002 mol/L NaN3, pH 7.4). The protein eluted from the affinity column was collected and dialyzed.

Enzyme-linked lectin assay

Microtitre plates (Shanghai Sangon Company, China) were coated with MBL in coating buffer (15 mmol/L Na2CO3-NaHCO3, pH 9.6) by overnight incubation at 4 °C. In this incubation and all the following steps reagent volumes of 100 μl were added to each well. TBS/TW (TBS/Ca2+ buffer containing 0.05% Tween 20) was employed in all washing steps. After being washed, the coated plates were incubated with BSA buffer (coating buffer containing 5 g/L BSA) at 37 °C for 2 h. After another wash, each type of bacteria (3×108 to 8×108 organisms/ml, measured as an absorbance of 1.0 at 540 nm) and Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP, 50 μg/ml TBS/Ca2+) were added to each well and incubated overnight at 4 °C. No bacteria were added to the 100% binding rate wells. After a final wash, the bound enzyme was estimated by adding 100 μl TMB buffer (Shanghai Sangon Co., China). The absorbance of the wells was determined at 450 nm by a multichannel spectrophotometry. Each well had a duplicate and final absorbance was taken as their mean value of absorbances.

RESULTS

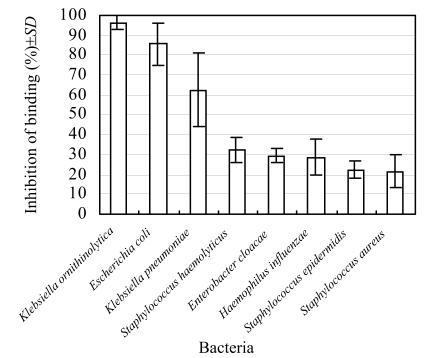

The ability of bacteria to bind to MBL was determined using ELLA. Bacteria inhibited HRP binding to MBL. The greater the inhibition, the stronger was the bacterial MBL binding. Different species exhibited varying degrees of MBL binding; this variation was noted between different genera and intra-species (Fig.1). All K. ornithinolytica (n=11) and E. coli (n=13) isolates were highly bond to MBL at high inhibition rates (96.4% and 85.5%). In contrast, S. haemolyticus (n=13), Enterobacter cloacae (n=10), S. epidermidis (n=13) exhibited relatively low MBL binding rates of 32.2%, 29.5% and 22.2%, respectively. There was variation in MBL binding abilities to different isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae and S. aureus (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

MBL binding to bacteria

Table 1.

MBL binding to bacteria as determined by ELLA

| Bacteria (number) | Inhibition of binding (%)±SD | Gram’s stain |

| Klebsiella ornithinolytica (n=11) | 96.4±3.3 | G− |

| Escherichia coli (n=13) | 85.5±10.7 | G− |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae (n=15) | 62.5±18.6 | G− |

| Staphylococcus haemolyticus (n=13) | 32.2±6.3 | G+ |

| Enterobacter cloacae (n=10) | 29.5±3.3 | G− |

| Haemophilus influenzae (n=9) | 28.6±9.1 | G− |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis (n=13) | 22.2±4.2 | G+ |

| Staphylococcus aureus (n=13) | 21.5±8.1 | G+ |

DISCUSSION

MBL is commonly present in mammalian sera. It is the first C-type lectin found to have an impact on the immune function. Its C-terminal lectin domain (CRD) binds to the sugar groups on microbial surfaces. Current knowledge of the molecular structure of MBL has resulted in several publications reporting its significant binding to microorganisms. These reports noted MBL binding to human immunodeficiency virus type 1, influenza A virus and various bacteria (Kilpatrick, 2002). Although MBL binding to a simple sugar has been previously studied, its binding to complex microbial surfaces has not been previously reported. We are aware of only one other study that examined comprehensive MBL binding (Neth et al., 2000). It used flow cytometry to investigate a variety of clinically relevant microorganisms.

In our study we detected the binding abilities of different bacteria with ELLA, which used HRP as a MBL ligand with numerous mannose units on its surface. Bacteria inhibit HRP binding to MBL when both bacteria and HRP are added to the same well. By comparing the inhibition rates of different bacteria, we can determine their MBL binding abilities. The bacterial membrane surfaces and components of sugar units on these surfaces determine the interaction with MBL. Gram-positive bacteria such as S. haemolyticus, S. epidermidis and S. aureus have thick layers of peptidoglycans and teichoic acids (some >50 layers). Peptidoglycans are composed of N-acetylglucosamines and N-acetyl-muramic acids. Both components are MBL ligands and thus can be recognized by MBL. Through this mechanism, MBL binds to these gram-positive bacteria. Although their layers of peptidoglycans and teichoic acids are much thinner (only one or two layers), gram-negative bacteria such as E. coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae have much more complex outer membranes. Their membranes are composed of lipopolysaccharide (LPS), phospholipids and some proteins. Among these, LPS is the most important in pathogenesis and is the MBL binding site. LPS is composed of several polysaccharides chains with repeating units of species-specific monosaccharides, such as galactose-rhamnose-mannose. Mannose is an MBL ligand and can bind MBL well. Our study showed that the MBL binding to gram-negative bacteria is stronger than its binding to gram-positive bacteria. Although this may be related to the difference in their membrane structures, further studies are needed to clarify this.

Although some bacterial isolates show identical intra-species MBL binding rates, different isolates of identical bacterial species may show different intra-species binding rates, such bacteria include E. coli, S. epidermidis, S. haemolyticus. One of the most interesting findings is the heterogeneity of MBL binding for K. pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae and S. aureus. These differences could be due to variation of sugar arrays on bacterial membranes. This finding emphasizes the need to examine several isolates of a specific bacterial species to determine MBL binding capacity for that bacterial species. Our results are similar to those of Kilpatrick’s (Kilpatrick, 2002).

MBL is a pattern recognition protein that contributes to immune defense by complement activation and communication with phagocytes. More and more evidence supports the theory that MBL deficiency alone or in combination with other deficiencies may contribute to a wide spectrum of clinical infections, especially among children (Turner and Hamvas, 2000; Garred et al., 1995; Aittoniemi et al., 1998; Summerfield et al., 1997). Currently there is no data concerning the minimal MBL levels needed to protect against specific bacterial infections. Required MBL levels may depend on the specific infectious agent and/or variations in host defense mechanisms. To determine such levels will remain very challenging until the various clearance mechanisms are elucidated. Most importantly, will MBL adjunctive therapy (Valdimarsson et al., 1998) be useful for infection control? All these areas await further study and offer significant opportunities for research.

Footnotes

Project (No. R02061) supported by Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province, China

References

- 1.Aittoniemi J, Baer M, Vesikari T, Miettinen A. Mannan binding lectin deficiency and concomitant immunodefects. Arch Dis Child. 1998;78:245–248. doi: 10.1136/adc.78.3.245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garred P, Madsen HO, Hofmann B, Svejgaard A. Increased frequency of homozygosity of abnormal mannan-binding-protein alleles in patients with suspected immunodeficiency. Lancet. 1995;346:941–943. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)91559-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Holmskov U, Malhotra R, Sim RB, Jensenius JC. Collectins: collagenous C-type lectins of the innate immune defense system. Immunol Today. 1994;15:67–74. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(94)90136-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jack DL, Klein NJ, Turner MW. Mannose-binding lectin: targeting the microbial world for complement attack and opsonophagocytosis. Immunol Rev. 2001;180:86–89. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2001.1800108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kilpatrick DC. Mannan-binding lectin: clinical significance and applications. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1572:401–413. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(02)00321-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Neth O, Jack DL, Dodds AW, Holzel H, Klein NJ, Turner MW. Mannose-binding lectin binds to a range of clinically relevant microorganisms and promotes complement deposition. Infect Immun. 2000;68:688–693. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.2.688-693.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Summerfield JA, Sumiya M, Levin M, Turner MW. Association of mutations in mannose binding protein gene with childhood infection in consecutive hospital series. B. M. J. 1997;314:1229–1232. doi: 10.1136/bmj.314.7089.1229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Turner MW, Hamvas RMJ. Mannose-binding lectin; structure, function, genetics and disease associations. Rev Immunogenet. 2000;2:305–322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Valdimarsson H, Stefansson M, Vikingsdottir T, Arason GJ, Koch C, Thiel S, Jensenius JC. Reconstitution of opsonizing activity by infusion of mannan-binding lectin (MBL) to MBL-deficient humans. Scand J Immunol. 1998;48:116–123. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.1998.00396.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]