Abstract

Since the identification of all the major drug-metabolising cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes and their major gene variants, pharmacogenetics has had a major impact on psychotherapeutic drug therapy. CYP enzymes are responsible for the metabolism of most clinically used drugs. Individual variability in CYP activity is an important reason for drug therapy failure. Variability in CYP activity may be caused by various factors, including endogenous factors such as age, gender and morbidity as well as exogenous factors such as co-medication, food components and smoking habit. However, polymorphisms, present in most CYP genes, are responsible for a substantial part of this variability. Although CYP genotyping has been shown to predict the majority of aberrant phenotypes, it is currently rarely performed in clinical practice.

Introduction

Psychiatric drug treatment is characterised by large interindividual differences in drug response and dosage requirement. The final clinical effect of a psychotropic drug depends on different factors influencing the pharmacogenetics and pharmacodynamics of the drug. The majority of these factors can be explained by individual variability.

Since all antipsychotics and antidepressives are highly lipophilic compounds, they are subject to extensive metabolism in the body before they are excreted. Additionally, many drugs have active metabolites contributing to the pharmacological effects of the drug. The metabolic capacity varies highly between individuals, with variable drug serum concentrations as a result. Especially when a drug has a narrow therapeutic index this strongly influences the effectiveness of drug therapy. The majority of drugs are metabolised by drug metabolising enzymes (DMEs), of which the cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes are especially important in metabolising antipsychotics and antidepressants. CYP activity depends on various factors, including genetic constitution. Polymorphisms in CYP enzymes are an important factor in the individual variability in metabolic capacity. Although receptors responsible for CYP expression are also polymorphic, functional polymorphisms have not been described thus far (recently reviewed by Okey et al.1).

At its place of action, the drug has again to cope with polymorphisms. Receptors, through which the psychotropic drugs exert their psychopharmacological effects, are also subject to genetic variation, consequently influencing drug response.2–4

Many antipsychotics and antidepressants have a narrow therapeutic range, with concentration dependent adverse effects occurring at concentrations only slightly higher than the dose required for psychiatric effect. Such adverse effects include antipsychotic-induced extrapyrimidal syndromes, such as Parkinsonism.5 Therefore patients would benefit from a ‘tailor made’ dosage. To accomplish this, classical therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) can be complemented with either CYP based genotyping or phenotyping. This review focuses on the factors that influence and predict CYP enzyme function, and how this knowledge can be used in clinical practice to optimize drug therapy.

CYP Enzymes

Historically, DME activity has been divided into two categories, phase I and phase II. Depending on the chemical nature of a drug, the former is characterised by oxidative metabolism resulting in either: pharmacological inactivation or activation, facilitated elimination and/or addition of reactive groups for subsequent phase II conjugation. The phase II DMEs are characterised by their ability to conjugate drugs using organic donor molecules such as glutathione, UDP-glucuronic acid, or acetyl coenzyme A. Phase I DMEs consist of CYP enzymes,flavin-containing monooxygenases, reductases, esterases and alcohol dehydrogenases. Phase II DMEs consist of glutathione S-transferases, N-acetyltransferase, UDP-glucuronosyltrans ferases, epoxide hydrolases and sulfotransferases.

CYP enzymes represent 70–80% of phase I metabolism and are responsible for the biotransformation of lipophilic drugs to polar metabolites,6,7 which can be excreted by the kidneys. The human hepatic CYP system consists of over 30 related isoenzymes with different, sometimes overlapping substrate specificities.8 The CYP enzymes have been categorised on the basis of their amino acid sequence in families, and subfamilies with individual genes.9,10 Family members are at least 40% identical and enzyme members with over 55% sequence homology are included in the same subfamily. The enzymes belonging to the families CYP1, CYP2 and CYP3 are responsible for the metabolism of exogenous compounds, including many drugs, (pro)carcinogens, (pro)mutagens and alcohols.

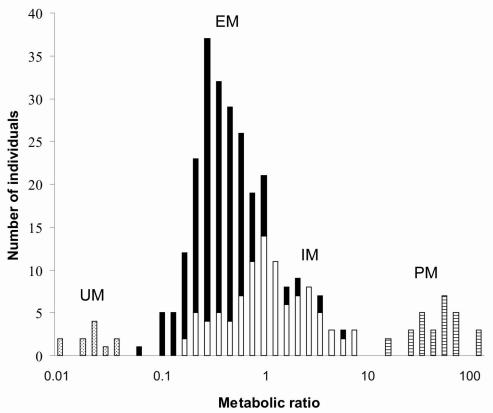

Variability in CYP activity may be caused by various factors. Besides endogenous factors such as age, gender and morbidity, exogenous factors such as co-medication, food components and smoking are important.11 Especially in psychiatry, co-medication is the rule rather than the exception. Several drugs are known to interfere with certain CYP enzymes by inhibition or induction, or by utilising those enzymes in their metabolism. An example of the latter is competition for CYP2D6 between antipsychotics and tricyclic antidepressants. If they are adjusted concomitantly, the metabolism of the latter will be hampered because of the higher affinity of the former for CYP2D6.12 In general, any substrate for a specific CYP enzyme is potentially capable of inhibiting the metabolism of another substrate. An up to date overview of CYP substrates (competitors), inducers and inhibitors is presented at http://medicine.iupui.edu/flockhart/. The intersubject variability in enzyme activity is for a large part determined by genetic factors. Most CYP enzymes are known to be polymorphic and CYP2D6, with over 80 allelic variants described so far, is extremely polymorphic (http://www.imm.ki.se/cypalleles/). Classically four phenotypes can be identified: poor metabolisers (PM), who are homozygous for one deficient allele or heterozygous for two different deficient alleles; intermediate metabolisers (IM), who are heterozygous for one deficient allele or carry two alleles that cause reduced activity; extensive metabolisers (EM), who have two wild-type alleles; and ultra rapid metabolisers (UM), who have multiple gene copies. This classification is based on the bimodal distribution of metabolic ratios (ratio between the urinary recovery of the parent drug and that of its major metabolite) in a population (Figure).

Figure.

Schematic presentation of the relationship between a parent drug and its major metabolite (metabolic ratio) and the CYP2D6 genotypes causing altered CYP2D6 activity. UM: ultra rapid metabolisers; EM: extensive metabolisers; IM: intermediate metabolisers; PM: poor metabolisers. Dotted bars: individuals with two or more gene copies; Filled bars: individuals with two wild-type alleles; Open bars: individuals who are heterozygous for one deficient allele or carry two alleles that cause reduced activity; Striped bars: individuals without any functional allele.

In psychiatry, CYP1A2, CYP2C9, CYP2C19, CYP2D6 and CYP3A4 are the most relevant CYP enzymes (Table 1). The activity of CYP2C9, CYP2C19 and CYP2D6 is polymorphically distributed in the population and related to the presence of a number of allelic variants with varying degrees of functional significance (Table 2). CYP1A2 and CYP3A4 activities are not polymorphically distributed, but are characterised by large interindividual variability, largely dependent on exogenous factors.

Table 1.

CYP enzymes and substrates.

| CYP1A2 | CYP2C9 | CYP2C19 | CYP2D6 | CYP3A4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antidepressants | |||||

| Amitriptyline | X | X | X | X | |

| Nortriptyline | X | ||||

| Citalopram | X | ||||

| Clomipramine | X | X | X | ||

| Desipramine | X | ||||

| Duloxetine | X | X | |||

| Fluoxetine | X | X | |||

| Fluvoxamine | X | X | |||

| Imipramine | X | X | X | ||

| Maprotiline | X | ||||

| Mianserin | X | ||||

| Paroxetine | X | ||||

| Sertraline | X | ||||

| Venlafaxine | X | ||||

| Antipsychotics | |||||

| Bromperidol | X | ||||

| Clozapine | X | ||||

| Chlorpromazine | X | ||||

| Haloperidol | X | X | X | ||

| Olanzapine | X | ||||

| Perphenazine | X | ||||

| Pimozide | X | ||||

| Risperidone | X | X | |||

| Quetiapine | X | ||||

| Thioridazine | X | ||||

| Ziprasidone | X | ||||

| Zuclopenthixol | X | ||||

Table 2.

CYP allele subgroups, characteristic mutation(s), enzyme activity and frequency among Caucasians, Africans and Orientals.

| Designation | Characteristic mutation(s) | Enzyme activity | Allelic frequency (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caucasian | African | Oriental | |||

| CYP2D6*1 | Wild-type | Normal | |||

| CYP2D6*2 | Several substitutions | Normal | 18 | 20 | 10 |

| CYP2D6*3 | A2549 deletion | Deficient | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| CYP2D6*4 | G1846A substitution | Deficient | 12–22 | 1–2 | 0–1 |

| CYP2D6*5 | Gene deletion | Deficient | 2–7 | 4–6 | 6 |

| CYP2D6*9 | G2613-A2615 deletion | Decreased | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| CYP2D6*10 | C100T substitution | Decreased | 1–2 | 4–6 | 51 |

| CYP2D6*17 | C1023T, C2850T substitutions | Decreased | 0 | 17–35 | 0 |

| CYP2D6*41 | C-1584G, G2988A substitutions | Decreased | 8 | 10 | 3 |

| CYP2D6 x2 | Gene(multi)duplication | Increased | 1–10 | 2–29 | 0–2 |

| CYP2C9*1 | Wild-type | Normal | |||

| CYP2C9*2 | C430T substitution | Decreased | 8–13 | 4 | 0 |

| CYP2C9*3 | A1075C substitution | Decreased | 6–9 | 2 | 2–3 |

| CYP2C19*1 | Wild-type | Normal | |||

| CYP2C19*2 | G681A substitution | Deficient | 13 | 13–25 | 23–32 |

| CYP2C19*3 | G636A substitution | Deficient | 0 | 0–2 | 6–10 |

CYP2D6

With more than 80 polymorphisms described, CYP2D6 is the most studied CYP enzyme in relation to drug metabolism. CYP2D6, or debrisoquine-4-hydroxylase, was the first drug metabolising enzyme reported to be polymorphic.13–15 Administration of either debrisoquine or sparteine revealed a tremendous inter-individual variation in plasma levels of the drugs following administration of the same dosage. Subsequently two metaboliser phenotypes were identified. Individuals who lack a functional gene were described as poor metabolisers (PM), while those with two wild-type alleles were described as extensive metabolisers (EM). Metabolic ratios are stable in an individual over time, indicating a limited influence of exogenic factors on CYP2D6 activity.16 However, inhibition or induction in case of co-medication may increase or decrease the metabolic ratio, respectively. Three major mutant alleles, now termed CYP2D6*3, *4 and *5,17 associated with the PM phenotype were found early on in Caucasians.18,19 With an allele frequency of maximal 22% in Caucasian populations (Table 2), CYP2D6*4 is the most common allele associated with the PM phenotype. Compared to CYP2D6*1, the wild-type allele, it has a mutation which results in a splicing defect.20 The allele is almost absent in Orientals which explains the low incidence (1%) of PM in this population compared to Caucasians.21 The frequency differences of CYP2D6*5, with deletion of the entire gene, are less pronounced, 2–7%, between different ethnic populations.22 While the CYP2D6 activity of UM, EM and PM (approximate incidence among Caucasians: 4%, 55% and 9%, respectively) is reasonably pronounced, CYP2D6 activity between IM (approximate incidence among Caucasians: 32%) varies widely (Figure). Heterozygote expression of different dysfunctional polymorphisms associated with partial enzyme dysfunction contributes to this variability. For instance, CYP2D6*9 and *10 mutations result in expression of enzymes with decreased catalytic activity.23,24 With a frequency of about 50%, the CYP2D6*10 allele is very common among Orientals, while it is almost absent in Caucasians.22,25 Recently, Raimundo et al. have identified a mutation (CYP2D6*41), affecting a putative nuclear factor κB-binding site downstream of the open reading frame, associated with a functional bimodality of the frequent CYP2D6*2 allele.26,27 Ultrarapid metabolisers (UM) are usually characterised by an allele defect of a completely different kind. Their CYP2D6 gene is duplicated or even multiduplicated.28,29 The frequency of this duplication/multiduplication varies widely between different ethnic populations.22

CYP2C9 and CYP2C19

In the CYP2C family both CYP2C9 and CYP2C19 have clinically relevant polymorphisms. Of CYP2C9, more than 50 polymorphisms have been described, but only 2 coding variants, termed CYP2C9*2 and *3, with functional consequence are common.30,31 CYP2C9*2 and *3 have allele frequencies in Caucasians of around 11% and 7%, respectively (Table 2). The allele frequencies in African and Oriental populations are significantly lower.32 CYP2C19 catalyses the metabolism of some tricyclic antidepressants and barbiturates. In addition to the wild-type gene, three allelic variants are known, which are associated with the complete absence of enzyme activity.33–35 The major defect CYP2C19 allele responsible for the PM phenotype is CYP2C19*2 with an allelic frequency of 13% in Caucasians, about 20% in Africans and maximal 32% in Orientals (Table 2). CYP2C19*3 is predominantly limited to Orientals with an allele frequency of around 8%.36

CYP1A2 and CYP3A4

CYP3A4 accounts for up to 30% of the total CYP present in liver and for the majority of CYP in human small intestine,37 and covers the metabolic clearance of the majority of drugs.6 Much effort has gone into finding clinically relevant polymorphisms in both the CYP3A4 and CYP1A2 genes, without success thus far. Some polymorphic sites in regulatory receptor genes have been found, but their functional importance remains unclear.1 However, both CYP1A2 and CYP3A4 activity show large interindividual variability. Their activity is especially influenced by a broad range of exogenic factors. Several drugs are known to either induce or inhibit CYP1A2 and CYP3A4 activity. CYP1A2 is inducible by the polyaromatic hydrocarbons in cigarette smoke.11,38 The dosages of clozapine were almost two times as high in smoking individuals compared to non-smoking individuals.39 Caffeine, a widely used phenotyping agent for CYP1A2, can give competition with CYP1A2 metabolised drugs.40,41 Inflammation negatively influences CYP1A2 activity,42 possibly by cytokine induced down-regulation of its expression.43,44 The high level of expression of CYP3A4 in the intestine may be the reason for its susceptibility to modulation by food constituents.45 Especially flavonoids in grapefruit juice are known to inhibit CYP3A4 activity.46

Interethnic Differences

Large differences in CYP allelic frequencies are not only seen between individuals but also between ethnic groups (Table 2). These differences in allele frequencies cannot be explained by spontaneous gene mutations and some compensating advantage must be suspected. It is generally believed that the drug-metabolising enzymes have evolved due to the interaction between plants and animals.47 As animals began consuming plants, the plants responded by evolving new toxic components. Animals adapted by evolving new drug metabolising enzymes to protect themselves. Not surprisingly, many currently used drugs derived from natural plant components are CYP substrates. Since food represents a broad range of CYP substrates, ethnic differences might reflect differences in diet that have evolved over thousands of years.48 A nice example is the increased CYP2D6 activity by the (multi)duplication of CYP2D6*2 alleles found in 1 to 2% of Swedes and as many as 29% of Ethiopians.28,49 Among Ethiopians, alleles containing multiple CYP2D6 gene copies have been frequently generated through recombination events in contrast to the CYP2D locus which has evolved in Caucasians. It is most likely that alkaloids, which display a nanomolar affinity for CYP2D6, have exerted this selection pressure.47 Allelic frequencies seen in CYP genes, between any individual, might also represent the evolution of balanced polymorphisms, in which heterozygotes have the advantage over homozygotes in survival.48

CYP Pharmacogenetics in Practice

In clinical practice CYP genotyping is primarily used in combination with TDM to explain aberrant medication levels, subsequently to adjust the drug dosage, or to switch medication, accordingly. In case of a mutated CYP, drug dosage is often fine tuned by trial and error. The development of genotype based dose recommendations could improve this process considerably.50–52 Steimer et al. developed a functional gene dose system for amitriptyline and nortriptyline which is based on so called ASCOC (allele specific change of concentration on identical background) values.52 The ASCOC describes the change in nortriptyline concentration attributable to a mutant allele compared with the wild-type. Assigning of semi-quantitative gene doses of 0, 0.5 or 1 to each allele instead of applying the current classification system (predicted phenotypes: 3 IM, 46 EM and 1 UM) produced significant nortriptyline concentration differences: gene doses of 0.5 (n=3), 1 (n=14), 1.5 (n=11), 2 (n=21) and 3 (n=1). An important advantage of this classification is that it accounted much better for the large group of IM, by taking into account the partial dysfunctional alleles of CYP2D6 (CYP2D6*9, *10 and *41). In this specific case the genotype information of CYP2D6 and CYP2C19 could be combined to predict the right dosage for amitriptyline and nortriptyline, thereby identifying patients with low or high risk for side effects in amitriptyline therapy. 53 Many hospitals do not have the facility to genotype all patients routinely. In contrast, in most hospitals the serum levels of many substrates as well as their (active) metabolites are determined as part of TDM. We found that metabolic ratios of amitriptyline, venlafaxine and risperidone corresponded notably with the genotype of CYP enzymes involved in their metabolism.54 When (routine) genotyping is not an option, TDM based dose recommendations could thus help to determine the right drug dosage.

Most of the relevant CYP mutations can be detected by fast and easy assays based on polymerase chain reaction (PCR), possibly completed with restriction-digestion.8 With increasing numbers of CYP mutations discovered each day, the accuracy of predicting the right phenotype also increases. Consequently, clinical genotyping becomes more complex and time consuming. This has led to the recent development of CYP tapered DNA micro arrays, which can test for all clinical relevant mutations at once.55,56

CYP polymorphisms are responsible for the development of a significant number of adverse drug reactions. It has been estimated that this accounts for at least 100,000 deaths and a cost estimate of 100 billion dollars a year in the USA.57 CYP genotyping allows the prediction of the metabolising phenotypes with high accuracy. With respect to antipsychotics and antidepressants, dosing of 50-60% of the drugs used is dependent, to a large extent, on the CYP2D6 and CYP2C19 enzymes.58 Therefore, in our psychiatric clinic TDM and genotyping for CYPD6 and CYP2C19 polymorphisms are routinely performed for all our hospitalised patients. In a recent prospective study among general practitioner patients treated with antidepressants or antipsychotics, CYP genotyping (CYP2C19 and CYP2D6) proved useful to explain aberrant medication levels for approximately 27% of the cases (J.E. Kootstra-Ros, M.J.M. van Weelden, J.W.J. Hinrichs, P.A.G.M. de Smet and J. van der Weide, unpublished data). However, an investigation among 510 laboratories, hospitals and universities throughout Australia and New Zealand showed that pharmacogenetic tests for the main polymorphically expressed CYP enzymes (CYP2C9, CYP2C19 and CYP2D6) are almost never performed in routine clinical practice.59 In contrast, especially in the USA, several laboratories offer individual CYP testing on a commercial base (e.g. http://www.healthanddna.com/professional/depression.html).

Conclusion

Psychiatric drug therapy is characterised by large interindividual differences in drug response and dosage requirement. With CYP polymorphisms contributing largely to the variability in drug response, genotyping is a useful tool in predicting a patient’s compliance with specific antipsychotics and antidepressants. Relevant CYP mutations can be detected relatively easily with PCR based assays or newly developed microarrays. Ethnicity must be considered when choosing which alleles are to be analysed. Many drugs are known to influence CYP enzyme activity and this should be taken into account, especially, in case of co-medication. Besides genetic variance, several exogenous factors, such as nutrients and smoking habit are known to effect CYP activity.

Despite the advantages of CYP genotyping in drug therapy, it is currently rarely performed in clinical practice. The lack of predictive CYP genotyping today cannot be explained by one specific cause. Among others, shortage of knowledge about genetics and pharmacogenetics among prescribers, and the lack of prospective data might play a role. Further prospective studies, showing a direct correlation between predictive genotyping and improvement of drug efficacy, could lead to the establishment of CYP genotyping.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared

References

- 1.Okey AB, Boutros PC, Harper PA. Polymorphisms of human nuclear receptors that control expression of drug-metabolizing enzymes. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2005;15:371–9. doi: 10.1097/01213011-200506000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arranz MJ, Munro J, Birkett J, et al. Pharmacogenetic prediction of clozapine response. Lancet. 2000;355:1615–6. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)02221-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arranz MJ, Kerwin RW. Advances in the pharmacogenetic prediction of antipsychotic response. Toxicology. 2003;192:33–5. doi: 10.1016/s0300-483x(03)00248-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lane HY, Chang YC, Chiu CC, et al. Association of risperidone treatment response with a polymorphism in the 5-HT(2A) receptor gene. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:1593–5. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.9.1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schillevoort I, de Boer A, van der Weide J, et al. Antipsychotic-induced extrapyramidal syndromes and cytochrome P450 2D6 genotype: a case-control study. Pharmacogenetics. 2002;12:235–40. doi: 10.1097/00008571-200204000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bertz RJ, Granneman GR. Use of in vitro and in vivo data to estimate the likelihood of metabolic pharmacokinetic interactions. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1997;32:210–58. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199732030-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Evans WE, Relling MV. Pharmacogenomics: translating functional genomics into rational therapeutics. Science. 1999;286:487–91. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5439.487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van der Weide J, Steijns LSW. Cytochrome P450 enzyme system: genetic polymorphisms and impact on clinical pharmacology. Ann Clin Biochem. 1999;36:722–9. doi: 10.1177/000456329903600604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nebert DW, Nelson DR, Coon MJ, et al. The P450 superfamily: update on new sequences, gene mapping, and recommended nomenclature. DNA Cell Biol. 1991;10:1–14. doi: 10.1089/dna.1991.10.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nelson DR, Koymans L, Kamataki T, et al. P450 superfamily: update on new sequences, gene mapping, accession numbers and nomenclature. Pharmacogenetics. 1996;6:1–42. doi: 10.1097/00008571-199602000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rostami-Hodjegan A, Amin AM, Spencer EP, Lennard MS, Tucker GT, Flanagan RJ. Influence of dose, cigarette smoking, age, sex, and metabolic activity on plasma clozapine concentrations: a predictive model and nomograms to aid clozapine dose adjustment and to assess compliance in individual patients. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2004;24:70–8. doi: 10.1097/01.jcp.0000106221.36344.4d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Glue P, Banfield C. Psychiatry, Psychopharmacology and P450s. Hum Psychopharmacol. 1996;11:97–114. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eichelbaum M, Spannbrucker N, Steinke B, Dengler HJ. Defective N-oxidation of sparteine in man: a new pharmacogenetic defect. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1979;16:183–7. doi: 10.1007/BF00562059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mahgoub A, Idle JR, Dring DG, et al. Polymorphic hydroxylation of debrisoquine in man. Lancet. 1977;2:584–6. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(77)91430-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tucker GT, Silas JH, Iyun AO, Lennard MS, Smith AJ. Polymorphic hydroxylation of debrisoquine. Lancet. 1977;2:718. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(77)90527-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dahl ML. Cytochrome P450 phenotyping/genotyping in patients receiving antipsychotics: useful aid to prescribing? Clin Pharmacokinet. 2002;41:453–70. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200241070-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dahl ML, Johansson I, Palmertz MP, Ingelman-Sundberg M, Sjoqvist F. Analysis of the CYP2D6 gene in relation to debrisoquin and desipramine hydroxylation in a Swedish population. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1992;51:12–7. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1992.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gaedigk A, Blum M, Gaedigk R, Eichelbaum M, Meyer UA. Deletion of the entire cytochrome P450 CYP2D6 gene as a cause of impaired drug metabolism in poor metabolizers of the debrisoquine/sparteine polymorphism. Am J Hum Genet. 1991;48:943–50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Skoda RC, Gonzalez FJ, Demierre A, Meyer UAl. Two mutant alleles of the human cytochrome P450 db1 gene (P450C2D1) associated with genetically deficient metabolism of debrisoquine and other drugs. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:5240–3. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.14.5240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gough AC, Miles JS, Spurr NK, et al. Identification of the primary gene defect at the cytochrome P450 CYP2D locus. Nature. 1990;347:773–6. doi: 10.1038/347773a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bertilsson L, Dahl ML, Tybring G. Pharmacogenetics of antidepressants: clinical aspects. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 1997;391:14–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1997.tb05954.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ingelman-Sundberg M. Genetic polymorphisms of cytochrome P450 2D6 (CYP2D6): clinical consequences, evolutionary aspects and functional diversity. Pharmacogenomics J. 2005;5:6–13. doi: 10.1038/sj.tpj.6500285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Broly F, Meyer UA. Debrisoquine oxidation polymorphism: phenotypic consequences of a 3-base-pair deletion in exon 5 of the CYP2D6 gene. Pharmacogenetics. 1993;3:123–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johansson I, Oscarson M, Yue QY, Bertilsson L, Sjoqvist F, Ingelman-Sundberg M. Genetic analysis of the Chinese cytochrome P4502D locus: characterization of variant CYP2D6 genes present in subjects with diminished capacity for debrisoquine hydroxylation. Mol Pharmacol. 1994;46:452–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang SL, Huang JD, Lai MD, Liu BH, Lai ML. Molecular basis of genetic variation in debrisoquine hydroxylation in Chinese subjects: Polymorphism in RFLP and DNA sequence of CYP2D6. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1993;53:410–8. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1993.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Raimundo S, Fischer J, Eichelbaum M, Griese EU, Schwab M, Zanger UM. Elucidation of the genetic basis of the common ‘intermediate metabolizer‘ phenotype for drug oxidation by CYP2D6. Pharmacogenetics. 2000;10:577–81. doi: 10.1097/00008571-200010000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Raimundo S, Toscano C, Klein K, et al. A novel intronic mutation, 2988G>A, with high predictivity for impaired function of cytochrome P450 2D6 in white subjects. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2004;76:128–38. doi: 10.1016/j.clpt.2004.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dahl ML, Johansson I, Bertilsson L, Ingelman-Sundberg M, Sjoqvist F. Ultrarapid hydroxylation of debrisoquine in a Swedish population. Analysis of the molecular genetic basis. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1995;274:516–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johansson I, Lundqvist E, Bertilsson L, Dahl ML, Sjoqvist F, Ingelman-Sundberg M. Inherited amplification of an active gene in the cytochrome P450 CYP2D locus as a cause of ultrarapid metabolism of debrisoquine. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:11825–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.24.11825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rettie AE, Wienkers LC, Gonzalez FJ, Trager WF, Korzekwa KR. Impaired (S)-warfarin metabolism catalysed by the R144C allelic variant of CYP2C9. Pharmacogenetics. 1994;4:39–42. doi: 10.1097/00008571-199402000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sullivan-Klose TH, Ghanayem BI, Bell DA, et al. The role of the CYP2C9-Leu359 allelic variant in the tolbutamide polymorphism. Pharmacogenetics. 1996;6:341–9. doi: 10.1097/00008571-199608000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Scordo MG, Aklillu E, Yasar U, Dahl ML, Spina E, Ingelman-Sundberg M. Genetic polymorphism of cytochrome P450 2C9 in a Caucasian and a black African population. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2001;52:447–50. doi: 10.1046/j.0306-5251.2001.01460.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.De Morais SM, Wilkinson GR, Blaisdell J, Meyer UA, Nakamura K, Goldstein JA. Identification of a new genetic defect responsible for the polymorphism of (S) mephenytoin metabolism in Japanese. Mol Pharmacol. 1994;46:594–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.De Morais SM, Wilkinson GR, Blaisdell J, Meyer UA, Nakamura K, Goldstein JA. The major genetic defect responsible for the polymorphism of S-mephenytoin metabolism in humans. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:15419–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ferguson RJ, De Morais SM, Benhamou S, et al. A new genetic defect in human CYP2C19: mutation of the initiation codon is responsible for poor metabolism of S-mephenytoin. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1998;284:356–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goldstein JA, Ishizaki T, Chiba K, et al. Frequencies of the defective CYP2C19 alleles responsible for the mephenytoin poor metabolizer phenotype in various Oriental, Caucasian, Saudi Arabian and American black populations. Pharmacogenetics. 1997;7:59–64. doi: 10.1097/00008571-199702000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shimada T, Yamazaki H, Mimura M, Inui Y, Guengerich FP. Interindividual variations in human liver cytochrome P-450 enzymes involved in the oxidation of drugs, carcinogens and toxic chemicals: studies with liver microsomes of 30 Japanese and 30 Caucasians. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1994;270:414–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Carrillo JA, Herraiz AG, Ramos SI, Gervasini G, Vizcaino S, Benitez J. Role of the smoking-induced cytochrome P450 (CYP)1A2 and polymorphic CYP2D6 in steady-state concentration of olanzapine. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2003;23:119–27. doi: 10.1097/00004714-200304000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van der Weide J, Steijns LS, van Weelden MJ. The effect of smoking and cytochrome P450 CYP1A2 genetic polymorphism on clozapine clearance and dose requirement. Pharmacogenetics. 2003;13:169–72. doi: 10.1097/00008571-200303000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Carrillo JA, Benitez J. Clinically significant pharmacokinetic interactions between dietary caffeine and medications. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2000;39:127–53. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200039020-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Raaska K, Raitasuo V, Laitila J, Neuvonen PJ. Effect of caffeine-containing versus decaffeinated coffee on serum clozapine concentrations in hospitalised patients. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2004;94:13–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Van der Molen-Eijgenraam M, Blanken-Meijs JT, Heeringa M, van Grootheest AC. Delirium due to increase in clozapine level during an inflammatory reaction. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2001;145:427–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bleau AM, Maurel P, Pichette V, Leblond F, du Souich P. Interleukin-1beta, interleukin-6, tumor necrosis factor-alpha and interferon-gamma released by a viral infection and an aseptic inflammation reduce CYP1A1, 1A2 and 3A6 expression in rabbit hepatocytes. Eur J Pharmacol. 2003;473:197–206. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(03)01968-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Levitchi M, Fradette C, Bleau AM, et al. Signal transduction pathways implicated in the decrease in CYP1A1, 1A2, and 3A6 activity produced by serum from rabbits and humans with an inflammatory reaction. Biochem Pharmacol. 2004;68:573–82. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2004.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Harris RZ, Jang GR, Tsunoda S. Dietary effects on drug metabolism and transport. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2003;42:1071–88. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200342130-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dahan A, Altman H. Food-drug interaction: grapefruit juice augments drug bioavailability--mechanism, extent and relevance. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2004;58:1–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ingelman-Sundberg M, Oscarson M, McLellan RA. Polymorphic human cytochrome P450 enzymes: an opportunity for individualized drug treatment. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1999;20:342–9. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(99)01363-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nebert DW. Polymorphisms in drug-metabolizing enzymes: what is their clinical relevance and why do they exist? Am J Hum Genet. 1997;60:265–71. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Aklillu E, Persson I, Bertilsson L, Johansson I, Rodrigues F, Ingelman-Sundberg M. Frequent distribution of ultrarapid metabolizers of debrisoquine in an ethiopian population carrying duplicated and multiduplicated functional CYP2D6 alleles. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1996;278:441–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kvist EE, Al-Shurbaji A, Dahl ML, Nordin C, Alvan G, Stahle L. Quantitative pharmacogenetics of nortriptyline: a novel approach. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2001;40:869–77. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200140110-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kirchheiner J, Brosen K, Dahl ML, et al. CYP2D6 and CYP2C19 genotype-based dose recommendations for antidepressants: a first step towards subpopulation-specific dosages. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2001;104:173–92. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2001.00299.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Steimer W, Zopf K, Von Amelunxen S, et al. Allele-specific change of concentration and functional gene dose for the prediction of steady-state serum concentrations of amitriptyline and nortriptyline in CYP2C19 and CYP2D6 extensive and intermediate metabolizers. Clin Chem. 2004;50:1623–33. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2003.030825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Steimer W, Zopf K, von Amelunxen S, et al. Amitriptyline or not, that is the question: pharmacogenetic testing of CYP2D6 and CYP2C19 identifies patients with low or high risk for side effects in amitriptyline therapy. Clin Chem. 2005;51:376–85. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2004.041327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.van der Weide J, van Baalen-Benedek EH, Kootstra-Ros JE. Metabolic ratios of psychotropics as indication of cytochrome P450 2D6/2C19 genotype. Ther Drug Monit. 2005;27:478–83. doi: 10.1097/01.ftd.0000162868.84596.c3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.de Leon J, Susce MT, Pan RM, Fairchild M, Koch WH, Wedlund PJ. The CYP2D6 poor metabolizer phenotype may be associated with risperdone adverse drug reactions and discontinuation. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66:15–27. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n0103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gerhold D, Lu M, Xu J, Austin C, Caskey CT, Rushmore T. Monitoring expression of genes involved in drug metabolism and toxicology using DNA microarrays. Physiol Genomics. 2001;5:161–70. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.2001.5.4.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ingelman-Sundberg M. Pharmacogenetics of cytochrome P450 and its application in drug therapy: the past, present and future. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2004;25:193–200. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2004.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kirchheiner J, Nickchen K, Bauer M, et al. Pharmacogenetics of antidepressants and antipsychotics: the contribution of allelic variations to the phenotype of drug response. Mol Psychiatry. 2004;9:442–73. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gardiner SJ, Begg EJ. Pharmacogenetic testing for drug metabolizing enzymes: is it happening in practice? Pharmacogenetics. 2005;15:365–9. doi: 10.1097/01213011-200505000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Caccia S. Metabolism of the newest antidepressants: comparisons with the related predecessors. IDrugs. 2004;7:143–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Prior TI, Baker GB. Interactions between the cytochrome P450 system and the second-generation antipsychotics. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2003;28:99–112. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bertilsson L, Dahl ML, Dalen P, Al-Shurbaji A. Molecular genetics of CYP2D6: Clinical relevance with focus on psychotropic drugs. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2002;53:111–22. doi: 10.1046/j.0306-5251.2001.01548.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gaedigk A, Ndjountche L, Leeder JS. Limited association of the 2988g>a single nucleotide polymorphisms with CYP2D641 in black subjects. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2005;77:228–30. doi: 10.1016/j.clpt.2004.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Human Cytochrome P450 (CYP) Allele Committee is located at http://www.imm.ki.se/cypalleles/ and was consulted at July 25, 2005.

- 65.Ikenaga Y, Fukuda T, Fukuda K, et al. The frequency of candidate alleles for CYP2D6 genotyping in the Japanese population with an additional respect to the -1584C to G substitution. Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 2005;20:113–6. doi: 10.2133/dmpk.20.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kirchheiner J, Brockmoller J. Clinical consequences of cytochrome P450 2C9 polymorphisms. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2005;77:1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.clpt.2004.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Leathart JB, London SJ, Steward A, Adams JD, Idle JR, Daly AK. CYP2D6 phenotype-genotype relationships in African-Americans and Caucasians in Los Angeles. Pharmacogenetics. 1998;8:529–41. doi: 10.1097/00008571-199812000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Teh LK, Ismail R, Yusoff R, Hussein A, Isa MN, Rahman AR. Heterogeneity of the CYP2D6 gene among Malays in Malaysia. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2001;26:205–11. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2710.2001.00347.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wennerholm A, Johansson I, Hidestrand M, Bertilsson L, Gustafsson LL, Ingelman-Sundberg M. Characterization of the CYP2D6*29 allele commonly present in a black Tanzanian population causing reduced catalytic activity. Pharmacogenetics. 2001;11:417–27. doi: 10.1097/00008571-200107000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]