Short abstract

Using semiquantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction assays, we investigated the expression of variant messenger RNAs relative to wild-type estrogen receptor (ER)-α messenger RNA in normal breast tissues and their adjacent matched breast tumor tissues. Higher ER variant truncated after sequences encoding exon 2 of the wild-type ER-α (ERC4) messenger RNA and a lower exon 3 deleted ER-α variant (ERD3) messenger RNA relative expression in the tumor compartment were observed in the ER-positive/PR-positive and the ER-positive subsets, respectively. A significantly higher relative expression of exon 5 deleted ER-α varient (ERD5) messenger RNA was observed in tumor components overall. These data demonstrate that changes in the relative expression of ER-α variant messenger RNAs occur between adjacent normal and neoplastic breast tissues. We suggest that these changes might be involved in the mechanisms that underlie breast tumorigenesis.

Keywords: breast cancer, estrogen receptor, tumorigenesis, variant messenger RNA

Abstract

Introduction:

Estrogen receptor (ER)-α and ER-β are believed to mediate the action of estradiol in target tissues. Several ER-α and ER-β variant messenger RNAs have been identified in both normal and neoplastic human tissues. Most of these variants contain a deletion of one or more exons of the wild-type (WT) ER messenger RNAs. The putative proteins that are encoded by these variant messenger RNAs would therefore be missing some functional domains of the WT receptors, and might interfere with WT-ER signaling pathways. The detection of ER-α variants in both normal and neoplastic human breast tissues raised the question of their possible role in breast tumorigenesis.

We have previously reported an increased relative expression of exon 5 deleted ER-α variant (ERD5) messenger RNA and of another ER-α variant truncated of all sequences following the exon 2 of the WT ER-α (ERC4) messenger RNA in breast tumor samples versus independent normal breast tissues. In contrast, a decreased relative expression of exon 3 deleted ER-α variant (ERD3) messenger RNA in tumor tissues and cancer cell lines versus independent normal reduction mammoplasty samples has recently been reported. These data were obtained in tissues from different individuals and possible interindividual differences cannot be excluded.

Aims:

The goal of this study was to investigate the expressions of ERC4, ERD5 and ERD3 variant messenger RNAs in normal breast tissues and their matched adjacent primary breast tumor tissues.

Materials and methods:

Eighteen cases were selected from the Manitoba Breast Tumor Bank, which had well separated and histopathologically characterized normal and adjacent neoplastic components. All tumors were classified as primary invasive ductal carcinomas. Six tumors were ER-negative/progesterone receptor (PR)-negative, nine were ER-positive/PR-positive, two were ER-positive/PR-negative, and one was ER-negative/PR-positive, as measured by ligand-binding assay. For each specimen, total RNA was extracted from frozen normal and tumor tissue sections and was reverse transcribed. The expressions of ERC4, ERD3 and ERD5 messenger RNAs relative to WT ER-α messenger RNA were investigated by previously validated semiquantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays performed using three different sets of primers.

Results:

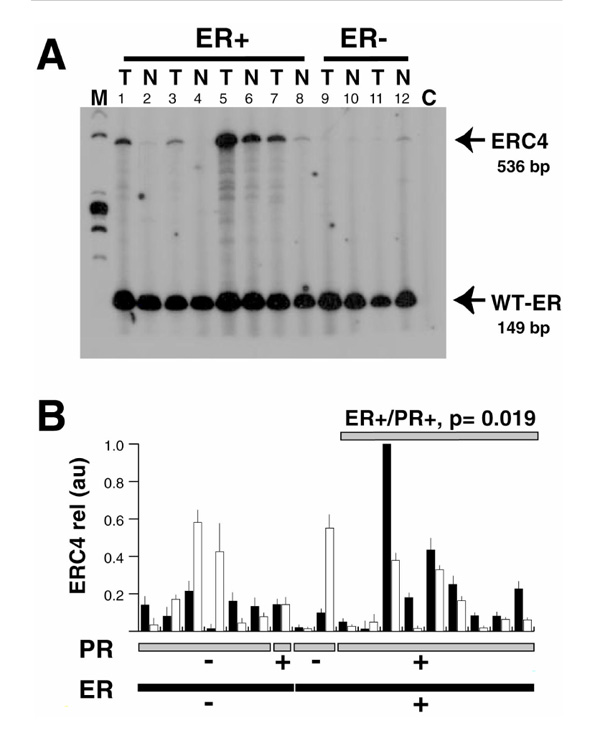

As shown Figure 1a, two PCR products were obtained that corresponded to WT ER and ERC4 messenger RNAs. For each case, the mean of the ratios obtained in at least three independent PCR experiments is shown for both normal and tumor compartments (Fig 1b). A statistically higher ERC4 messenger RNA relative expression was found in the neoplastic components of ER-positive/PR-positive tumors, as compared with matched adjacent normal tissues (n = 9; P = 0.019, Wilcoxon signed-rank test).

Two PCR products were obtained that corresponded to WT ER and ERD3 messenger RNAs (Fig 2a). A significantly higher expression of ERD3 messenger RNA was observed in the normal compared with the adjacent neoplastic components of ER-positive subset (n =8; P =0.023, Wilcoxon signed-rank test; Fig 2b).

Two PCR products were obtained that corresponded to WT ER and ERD5 complementary DNAs (Fig 3a). As shown in Figure 3b, a statistically significant higher relative expression of ERD5 messenger RNA was observed in tumor components when this expression was measurable in both normal and adjacent tumor tissues (n =15; P =0.035, Wilcoxon signed-rank test).

Discussion:

A statistically significant higher ERC4 messenger RNA expression was found in ER-positive/PR-positive tumors as compared with matched normal breast tissues. ERC4 variant messenger RNA has previously been demonstrated to be more highly expressed in ER-positive tumors that showed poor as opposed to tumors that showed good prognostic characteristics. Interestingly, we also have reported similar levels of expression of ERC4 messenger RNA in primary breast tumors and their concurrent axillary lymph node metastases. Taken together, these data suggest that the putative role of the ERC4 variant might be important at different phases of breast tumorigenesis and tumor progression; alteration of ERC4 messenger RNA expression and resulting modifications in ER signaling pathway probably occur before breast cancer cells acquire the ability to metastasize. Transient expression assays revealed that the protein encoded by ERC4 messenger RNA was unable to activate the transcription of an estrogen-responsive element-reporter gene or to modulate the wild-type ER protein activity. The biologic significance of the changes observed in ERC4 messenger RNA expression during breast tumorigenesis remains to be determined.

A higher relative expression of ERD3 messenger RNA in the normal breast tissue components compared with adjacent neoplastic tissue was found in the ER-positive subgroup. These data are in agreement with the recently published report of Erenburg et al, who showed a decreased relative expression of ERD3 messenger RNA in neoplastic breast tissues compared with independent reduction mammoplasty and breast tumor. Transfection experiments showed that the activation of the transcription of the pS2 gene by estrogen was drastically reduced in the presence of increased ERD3 expression. The authors hypothesized that the reduction in ERD3 expression could be a prerequisite for breast carcinogenesis to proceed.

We observed a significantly higher relative expression of ERD5 messenger RNA in breast tumor components compared with matched adjacent normal breast tissue. These data confirm our previous observations performed on unmatched normal and neoplastic human breast tissues. Upregulated expression of this variant has already been reported in ER-negative/PR-positive tumors, as compared with ER-positive/PR-positive tumors, suggesting a possible correlation between ERD5 messenger RNA expression and breast tumor progression. Even though it has been suggested that ERD5 could be related to the acquisition of insensitivity to antiestrogen treatment (ie tamoxifen), accumulating data refute a general role for ERD5 in hormone-resistant tumors. Only ER-positive pS2-positive tamoxifen-resistant tumors have been shown to express significantly higher levels of ERD5 messenger RNA, as compared with control tumors. Taken together, these data suggest that the exact biologic significance of ERD5 variant expression during breast tumorigenesis and breast cancer progression, if any, remains unclear.

In conclusion, we have shown that the relative expressions of ERC4 and ERD5 variant messenger RNAs were increased in human breast tumor tissue, as compared with normal adjacent tissue, whereas the expression of ERD3 variant messenger RNA was decreased in breast tumor tissues. These results suggest that the expressions of several ER-α variant messenger RNAs are deregulated during human breast tumorigenesis. Further studies are needed to determine whether these changes are transposed at the protein level. Furthermore, the putative role of ER-α variants in the mechanisms that underlie breast tumorigenesis remains to be determined.

Introduction

Estrogen receptor (ER)-α and ER-β are believed to mediate the action of estradiol in target tissues [1,2]. These two receptors, which belong to the steroid/retinoic acid/thyroid receptor superfamily [3], contain several structural and functional domains [4] that are encoded by two messenger RNAs that contain eight exons [5,6]. Upon ligand binding, ER-α and ER-β proteins recognize specific estrogen-responsive elements located in DNA in the proximity of target genes, and through interactions with several coactivators modulate the transcription of these genes [7].

Several ER-α and ER-β variant messenger RNAs have been identified in both normal and neoplastic human tissues [8,9,10,11,12]. Most of these variants contain a deletion of one or more exons of the wild-type (WT)-ER messenger RNA. The putative proteins encoded by these variant messenger RNAs would therefore be missing some functional domains of the WT receptors and might interfere with WT ER signaling pathways. Indeed, in vitro functional studies have shown that some recombinant ER-α variant proteins can affect estrogen-regulated gene transcription. For example, the variant protein encoded by exon 3 deleted ER-α variant (ERD3) messenger RNA, which is missing the second zinc finger of the DNA binding domain, has been shown [13] to have a dominant negative activity on WT ER-α receptor action. A similar dominant negative activity has been observed for ERD5 variant protein (encoded by an ER-α variant messenger RNA deleted in exon 5 sequences), which is missing a part of the hormone-binding domain of the WT molecule [14]. Interestingly, a constitutive hormone-independent activity [15] and a WT enhancing activity [16] have also been attributed to ERD5 variant protein in different systems. The relevance of the levels achieved in these transfection experiments to in vivo expression remains unclear. It should also be noted that these functional activities are likely to be cell-type and promoter specific [8].

The discovery that these ER-α variants are expressed in both normal and neoplastic human breast tissues, however, raised the question of their possible role in breast tumorigenesis [8]. We have previously reported an increased relative expression of ERD5 messenger RNA and of ERC4 messenger RNA, another ER-α variant messenger RNA that is truncated of all sequences following the exon 2 of the WT ER-α [17], in breast tumor samples versus independent normal breast tissues [18,19]. In contrast, Erenburg et al [20] recently reported a decreased relative expression of ERD3 messenger RNA in tumor tissues and cancer cell lines versus independent normal reduction mammoplasty samples. Those data, which suggested that alteration in ERD5, ERD3 and clone 4 messenger RNA expression might occur during breast tumorigenesis, were obtained in tissues from different individuals, and possible interindividual differences cannot be excluded.

In order to clarify this issue, we investigated the expression of these three variant messenger RNAs in normal breast tissues and their matched adjacent primary breast tumor tissues.

Materials and methods

Human breast tissues and reverse transcription

In order to investigate the expressions of ERC4, ERD3 and ERD5 messenger RNA relative to WT-ER messenger RNA within matched normal and breast tumor tissues, eighteen cases were selected in the National Cancer Institute of Canada Manitoba Breast Tumor Bank (Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada), which had well separated and histopathologically characterized normal and adjacent neoplastic components. The Tumor Bank, which serves as a national Tumor Bank and is funded by the National Cancer Institute of Canada, has been reviewed and received approval from the Ethics Review Committee, Faculty of Medicine, University of Manitoba.

The processing of specimens collected in the Manitoba Breast Tumor Bank has already been described [21]. Briefly, each specimen had been rapidly frozen as soon as possible after surgical removal. A portion of the frozen tissue block was processed to create a paraffin-embedded tissue block that was matched and oriented relative to the remaining frozen block. These paraffin blocks provide high quality histologic sections, which are used for pathologic interpretation and assessment, and are mirror images of the frozen sections used for RNA extractions.

For each case, tumor and adjacent normal tissues from the same individual were histologically characterized by observation of paraffin sections. The presence of normal ducts and lobules, as well as the absence of any atypical lesion, were confirmed in all normal tissue specimens. All tumor components were classified as primary invasive carcinomas. Seven tumors were ER-negative (ER < 3 fmol/mg protein), with progesterone receptor (PR) values ranging from 2.2 to 11.2f mol/mg protein, as measured using ligand-binding assay [22]. Axillary nodal metastases were observed in five of these cases. Eleven tumors were ER-positive (ER values ranged from 3.5 to 159 fmol/mg protein), with PR values ranging from 5.8 to 134 fmol/mg protein. These tumors spanned a wide range of grades (grades 5-9, median 7.5), which were determined using the Nottingham grading system [23]. Axillary nodal metastases were observed in one of these cases. Patients were from 39 to 86 years old (median 54 years). Total RNA was extracted from frozen tissue sections and reverse-transcribed in a final volume of 25 μ l as previously described [18]. The quality of complementary DNAs obtained was assessed by amplification of the ubiquitously expressed glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase complementary DNA, as described previously [18].

Triple primer polymerase chain reaction

A previously described triple primer polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay has been used to coamplify ERC4 and WT-ER-α complementary DNAs [19,24]. Primers used consisted of ERU primer (5' -TGTGCAATGACTATGCTTCA-3', sense, located in WT-ER exon 2, position 792-811), ERL primer (5' -GCTCTTCCTCCTGTTTTTAT-3', antisense, located in WT-ER exon 3, position 940-921), and C4L primer (5' -TTTCAGTCTTCAGATACCCCAG-3', antisense, located in ERC4 sequence, position 1336-1315). The given positions correspond to the published sequences for WT-ER [1] and ERC4 [17].

PCR amplifications were performed as previously described [18,24]. Briefly, 0.2 μ l reverse transcription mixture was amplified in a final volume of 15 μ l, in the presence of 1.5 μ Ci of [α-32P] deoxycytidine triphosphate (dCTP; 3000 Ci/mmol), 4 ng/μl of each primer and 0.3 unit of Taq DNA polymerase. Each cycle consisted of 1min at 94°C, 30s at 60°C and 1min at 72°C. PCR products were then separated on 6% polyacrylamide gels containing 7mol/l urea (polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis). After electrophoresis, the gels were dried and autoradiographed. Two PCR products were obtained, which were identified by subcloning and sequencing, performed as previously described [18]. PCR products migrating with the apparent size of 149 and 536 base pairs were shown to correspond to WT-ER and ERC4 complementary DNAs, respectively.

Polymerase chain reaction

Two different primer sets, ERD3 and ERD5, were used to coamplify WT-ER and ERD3 complementary DNAs, and WT-ER and ERD5 complementary DNAs, respectively. ERD3 primer set consisted of D3U primer (5' -TGTGCAATGACTATGCTTCA-3', sense, located in WT-ER exon 2, position 792-811) and D3L primer (5' -TGTTCTTCTTAGAGCGTTTGA-3', antisense, located in WT-ER exon 4, position 1145-1125). ERD5 primer set consisted of D5U primer (5' -CAGGGGTGAAGTGGGGTCTGCTG-3', sense, located in WT-ER exon 4, position 1060-1082) and D5L primer (5'-α TGCGGAACCGAGATGATGTAGC-3', anti-sense, located in WT-ER exon 6, position 1542-1520). The given positions correspond to published sequences for WT-ER [1].

PCR amplifications were performed and PCR products analyzed as previously described [18]. Briefly, 0.2 μ l reverse transcription mixture was amplified in a final volume of 15 μ l, in the presence of 1.5 μ Ci of [α-32P] dCTP (3000 Ci/mmol), 4ng/μ l of each primer of the primer set considered (ERD3 or ERD5 primer set) and 0.3 unit of Taq DNA polymerase. Each cycle consisted of 30s at 94°C, 30s at 60°C and 30s at 72°C. PCR products were then separated on 6% polyacrylamide gels containing 7mol/l urea (polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis). Following electrophoresis, the gels were dried and autoradiographed. For each PCR, two PCR products were obtained, which were identified by subcloning and sequencing. PCR products migrating with the apparent size of 354 and 483 base pairs, using ERD3 and ERD5 primer set, respectively, were shown to correspond to WT-ER complementary DNA. PCR products migrating with the apparent size of 237 and 344 base pairs, using ERD3 and ERD5 primer set, were shown to correspond to ERD3 and ERD5 complementary DNAs, respectively.

Quantitation and statistical analysis

For each experiment, bands corresponding to the variant messenger RNA (ie ERC4, ERD3 or ERD5) and to WT-ER were excised from the gel and counted in a scintillation counter. For each set of primers (ie ERC4, ERD3 and ERD5 primer set) and for each sample, four independent PCR assays were performed. The ratios between ERC4, ERD3 or ERD5 signals and corresponding WT-ER signal were calculated. For each experiment, in order to correct for overall interassay variations (due to different batches of radiolabelled [α -32P] dCTP or of Taq DNA polymerase), the ratio observed in the same particular tumor (case number 12) was arbitrarily given the value of one and all other ratios expressed relatively. Under our experimental conditions, some samples did not have measurable levels (ie signal lower than twice the background value) of ERD3 or ERD5 variant messenger RNAs (see Figs 2a and 3a) in any of the four repetitions performed. Only cases that had detectable levels in at least three of the replicates in both their normal and tumor compartments were included in the statistical analysis. The significance of the differences in the relative levels of expression of ERC4, ERD3 and ERD5 messenger RNAs between matched normal and tumor components was determined using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test.

Figure 2.

Comparison of the relative expression of exon 3 deleted estrogen receptor (ER) variant (ERD3) messenger RNA between breast tumor and adjacent matched normal breast samples. (A) Total RNA extracted from frozen tissue sections from tumor (T) and adjacent normal (N) breast tissue samples was reverse transcribed and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was amplified using D3U and D3L primers. Radioactive PCR products were separated on a 6% acrylamide gel and visualized by autoradiography. Bands migrating at 354 and 237 base pairs were identified as corresponding to wild-type (WT)-ER and ERD3 variant messenger RNA, respectively. C, negative control (no complementary DNA added during the PCR reaction). (B) For each case, signals corresponding to ERD3 variant messenger RNA were quantified and expressed in arbitrary units for tumor (black column) and normal (white column) components. For each sample, the mean and the standard deviation of at least three different polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays are indicated. Cases are sorted by ER status (black bottom lane) and progesterone receptor (PR) status (gray bottom lane). Samples that failed to have three measurable signals in the four experiments performed in both normal and neoplastic components were not included in the statistical analysis. The significance of the differences between tumor and normal matched components within each subgroup, as tested using the Wilcoxon matched-pair test, is indicated where P <0.05. M, molecular weight marker.

Figure 3.

Comparison of the relative expression of exon 3 deleted estrogen receptor (ER) variant (ERD3) messenger RNA between breast tumor and adjacent matched normal breast samples. (A) Total RNA extracted from frozen tissue sections from tumor (T) and adjacent normal (N) breast tissue samples was reverse transcribed and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplified using D5U and D5L primers. Radioactive PCR products were separated on a 6% acrylamide gel and visualized by autoradiography. Bands that migrated at 483 and 344 base pairs were identified as corresponding to wild-type (WT)-ER and exon 5 deleted ER variant (ERD5) messenger RNA, respectively. C, negative control (no complementary DNA added during the PCR reaction). (B) For each case, signals corresponding to ERD5 variant messenger RNA were quantified and expressed in arbitrary units for tumor (black column) and normal (white column) components. For each sample, the mean and the standard deviation of at least three different PCR assays are indicated. Cases are sorted by ER status (black bottom lane) and progesterone receptor (PR) status (gray bottom lane). Samples that failed to have three measurable signals in the four experiments performed in both normal and neoplastic components were not included in the statistical analysis. The significance of the differences between tumor and normal matched components within each subgroup, as tested using the Wilcoxon matched-pair test, is indicated where P <0.05. m, molecular weight marker.

Results

Relative expression of ERC4 messenger RNA in matched normal and breast tumor tissues

A recently described triple-primer PCR assay was used to compare the relative expressions of ERC4 messenger RNA between adjacent normal and tumor components [19,24]. In this assay, three primers are used simultaneously during the PCR: the upper primer is able to recognize both WT-ER and ERC4 complementary DNA sequences, whereas the two lower primers are specific for each complementary DNA. Competitive amplification of two PCR products occurs, giving a final PCR product ratio related to the initial input of target complementary DNAs. This approach has been validated previously both by competitive amplification of spiked complementary DNA preparations [19] and by comparison to RNAse protection assays [24].

As shown Figure 1a, two PCR products were obtained, which migrated at the apparent size of 149 and 536 base pairs. These products have been shown to correspond to WT-ER and ERC4 messenger RNAs, respectively [24]. One should note the presence, in samples where WT-ER and ERC4 signals are high (Fig 1a, lane 5), of minor additional bands, one of which has been previously identified as corresponding to exon 2-duplicated ER-α variant complementary DNA [24]. The presence of these minor PCR products did not interfere with the quantitative aspect of the triple-primer PCR assay [24]. For each case, the mean of the ratios obtained in at least three independent PCR experiments, expressed in arbitrary units, is shown for both normal and tumor compartments (Fig 1b). A higher clone 4 messenger RNA relative expression in the tumor compartment was observed in 12 out of 18 cases. This difference did not, however, reach statistical significance (P = 0.47, Wilcoxon signed-rank test). When considering only the ER-positive/PR-positive subset (n = 9), as measured by the ligand-binding assay, a statistically higher ERC4 messenger RNA relative expression was found in the neoplastic components, as compared with matched adjacent normal tissues (P = 0.019, Wilcoxon signed-rank test).

Figure 1.

Comparison of the relative expression of estrogen receptor (ER) variant truncated after sequences encoding exon 2 of the wild-type (WT) ER-α (ERC4) messenger RNAs between breast tumor and adjacent matched normal breast samples. (A) Total RNA extracted from frozen tissue sections from tumor (T) and adjacent normal (N) breast tissue samples was reverse transcribed and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was amplified using ERU, ERL and C4L primers (see text). Radioactive PCR products were separated on a 6% acrylamide gel and visualized by autoradiography. Bands migrating at 149 and 536 base pairs were identified as corresponding to WT-ER and ERC4 variant messenger RNA, respectively. C, negative control (no complementary DNA added during the PCR reaction). (B) For each case, signals corresponding to ERC4 variant messenger RNA were quantified (see text) and expressed in arbitrary units for tumor (black column) and normal (white column) components. For each sample, the mean and the standard deviation of at least three different PCR assays are indicated. Cases are sorted by ER status (black bottom lane) and progesterone receptor (PR) status (gray bottom lane). The significance of the differences between tumor and normal matched components within each subgroup, as tested using the Wilcoxon matched-pair test, is indicated where P <0.05. M, molecular weight marker (fx174 Haelll digest, Gibco BRL, Grand Island, New York, NY).

Relative expression of ERD3 messenger RNA in matched normal and breast tumor tissues

A PCR assay, performed using primers annealing to sequences in exons 2 and 4, was used to investigate ERD3 messenger RNA expression relative to WT-ER in these 18 matched cases. We [18] and others [25] have previously shown that the coamplification of WT-ER and an exon-deleted ER-α variant complemetary DNA resulted in the amplification of two PCR products, the relative signal intensity of which provided a previously validated measurement of exon-deleted ER-α variant expression.

Two PCR products were obtained, that migrated with an apparent size of 354 and 237 base pairs (Fig 2a). These fragments were shown by subcloning and sequencing to correspond to WT-ER and ERD3 messenger RNAs (data not shown). The relative ERD3 signal was measurable in the normal and in the tumor compartments of 13 cases (Fig 2b). Out of these 13 cases, ERD3 messenger RNA expression was higher in the normal compartment in 10 cases. This difference, however, did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.057, Wilcoxon signed-rank test). A significantly higher expression of ERD3 messenger RNA in the normal compared with the adjacent neoplastic components was found when only the ER-positive subset was considered, however (n = 8; P = 0.023, Wilcoxon signed-rank test).

Relative expression of ERD5 messenger RNA in matched normal and breast tumor tissues

Using primers annealing to sequences in exons 4 and 6 of WT-ER, we also investigated the relative expression of ERD5 messenger RNA in these 18 matched cases. Two PCR products were detected, that migrated at an apparent size of 483 and 344 base pairs, and that have previously been shown to correspond to WT-ER and ERD5 complementary DNAs, respectively (Fig 3a). As shown in Fig 3b, a statistically significant higher relative expression of ERD5 messenger RNA was observed in tumor components when this expression was measurable in both normal and adjacent tumor tissues (n = 15; P = 0.035, Wilcoxon signed-rank test).

Discussion

The expression of ERC4, ERD3 and ERD5 variant messenger RNAs relative to WT-ER messenger RNA expression within adjacent normal and neoplastic human breast tissues was investigated using previously described semi-quantitative reverse transcription PCR assays [18,19,24]. These assays allow the determination of the expression of ER-α variant messenger RNA relative to WT-ER messenger RNA using a very small amount of starting material, and offer the advantage of allowing investigators to work with histopathologically well characterized human breast tissue regions. It should be noted, however, that the sensitivities of the assays used in this study differed from each other. The triple-primer PCR assay has previously been set up to allow the determination of ERC4 relative expression in tumor samples with very low ER levels, as measured by ligand-binding assay [24].

We showed that, in samples with a detectable level of ERC4 messenger RNA using a standardized RNAse protection assay, the relative expression of this variant to WT-ER messenger RNA expression was similar to the relative expression of ERC4 PCR product obtained after triple-primer PCR [24]. Triple-primer PCR assay applied to the detection of ERC4 messenger RNA in 18 matched normal and tumor breast tissues gave a measurable value of expression in 36 out of the 36 samples studied. This contrasts with the detection of 30 out of 36 and 33 out of 36 obtained using ERD3-specific and ERD5-specific primers, respectively. These differences in sensitivity probably result from different primer set efficiencies under our experimental conditions.

A higher ERC4 messenger RNA relative expression in tumor components compared with the normal adjacent tissue component has been observed in the ER-positive/PR-positive subgroup. This result is in agreement with our previous data [19] obtained by comparing ERC4 messenger RNA expression between independent normal reduction mammoplasty samples and a group of ER-positive/PR-positive breast tumors. Even though a higher ERC4 messenger RNA relative expression was observed in the tumor component of 12 out of 18 cases, this difference did not reach statistical significance. This absence of statistically significant differences might result from the low number of matched cases studied or from the different biology of ER-negative cases. Further studies are needed to clarify this issue and to draw any conclusion regarding the expression of ERC4 messenger RNA in ER-negative samples.

ERC4 variant messenger RNA has previously been shown [26] to be more highly expressed in ER-positive tumors that show poor prognostic characteristics (presence of more than four axillary lymph nodes, tumor size >2 cm, aneuploid, high percentage S-phase cells) than in ER-positive tumor with good prognostic characteristics (absence of axillary lymph node, tumor size <2 cm, diploid, low percentage S-phase cells). Moreover, in that previous study, a higher ERC4 messenger RNA expression was also observed in ER-positive/PR-negative tumors, as compared with ER-positive/PR-positive tumors. interestingly, we have also recently reported similar levels of expression of ERC4 messenger RNA in primary breast tumors and their concurrent axillary lymph node metastases [24]. Taken together, these data suggest that the putative role of the ERC4 variant might be important at different phases of breast tumorigenesis and tumor progression; alteration in ERC4 messenger RNA expression and resulting modifications in ER signaling pathway probably occur before breast cancer cells acquire the ability to metastasize. Transient expression assays revealed that the protein encoded by ERC4 messenger RNA was unable to activate the transcription of an estrogen responsive element-reporter gene or to modulate WT-ER protein activity [17]. The biologic significance of the changes observed in ERC4 messenger RNA expression during breast tumorigenesis and tumor progression therefore remains unclear.

A trend toward a higher relative expression of ERD3 messenger RNA in the normal breast tissue components compared with adjacent neoplastic tissue was found (10 out of 13 cases), which reached statistical significance when the ER-positive subgroup only was considered. These data are in agreement with the recently published report of Erenburg et al [20] who showed a decreased relative expression of ERD3 messenger RNA in neoplastic breast tissues and breast cancer compared with independent reduction mammoplasty and breast tumor. Transfection experiments performed by those investigators showed that the activation of the transcription of the pS2 gene by estrogen was drastically reduced in the presence of increased ERD3 expression. Moreover, ERD3 transfected MCF-7 human breast cancer cells had a reduced saturation density, exponential growth rate and in vivo invasiveness, as compared with control cells. These data led the authors to hypothesize that the reduction of ERD3 expression could be a prerequisite for breast carcinogenesis to proceed. They suggested that if high levels of ERD3 could attenuate estrogenic effects in normal breast tissue, low levels might lead to an excessive and unregulated mitogenic action of estrogen.

We observed a significantly higher relative expression of ERD5 messenger RNA in breast tumor components compared with matched adjacent normal breast tissue. These data confirm our previous observations [18] performed on unmatched normal and neoplastic human breast tissues. Upregulated expression of this variant has already been reported in ER-negative/PR-positive tumors, as compared with ER-positive/PR-positive tumors [15,27], suggesting a possible correlation between ERD5 messenger RNA expression and breast tumor progression. Interestingly, ERD5 messenger RNA can be detected in human pituitary adenomas, but not in normal pituitary samples [28]. This underscores the putative involvement of this ER variant in other tumor systems. Even though it has been suggested that ERD5 could be related to the acquisition of insensitivity to antiestrogen treatment (ie tamoxifen) [29,30], accumulating data refute a general role for ERD5 in hormone-resistant tumors [14,25,31,32]. Only ER-positive pS2-positive tamoxifen resistant tumors have been shown to express significantly higher levels of ERD5 messenger RNA, as compared with control tumors [33]. Taken together, these data suggest that the exact biologic significance of ERD5 variant expression during breast tumorigenesis and breast cancer progression, if any, remains unclear.

Among all the articles published so far on ER variants, only one has investigated ER variant expression between normal and neoplastic matched samples. Okada et al [33] recently reported a study performed on 15 cases. They observed an apparent difference in ER variant messenger RNA expression between adjacent normal and tumor samples. That study was performed using a less sensitive PCR approach, however, because PCR products were stained using ethidium bromide, and no attempt was made to quantify ER variant messenger RNA expression relative to WT-ER messenger RNA expression.

In conclusion, we have shown that the relative expression of ERC4 and ERD5 variant mRNAs was increased in human breast tumor tissue, as compared with normal adjacent tissue, whereas the expression of ERD3 variant messenger RNA was decreased in breast tumor tissues. These results, which confirm previous data obtained on independent human breast tissue samples [18,19], suggest that the expressions of several ER-α variant messenger RNAs are deregulated during human breast tumorigenesis. Further studies are needed to determine whether these changes are transposed at the protein level. Only the use of specific antibodies that are able to recognize specifically the different ER variant proteins putatively encoded by these variant messenger RNAs will allow this issue the be addressed. Furthermore, the putative role of ER-α variants in the mechanisms that underlie breast tumorigenesis remain to be determined.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by a grant from the US Army Medical Research and Materiel Command (DAMD17-95-1-5015). The Manitoba Breast Tumor Bank is supported by funds from the National Cancer Institute of Canada (NCIC). EL is a recipient of an US Army Medical Research and Materiel Command Postdoctoral Fellowship (DAMD17-96-1-6174), PHW is a Medical Research Council of Canada (MRC) Clinician-Scientist, and LCM is an MRC Scientist.

References

- Green S, Walter P, Kumar V, et al. Human oestrogen receptor cDNA: sequence, expression and homology to v-erb alpha. . Nature. 1986;320:134–139. doi: 10.1038/320134a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosselman S, Polman J, Dijkema R. ER-beta: identification and characterization of a novel human estrogen receptor. FEBS Lett . 1996;392:49–53. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00782-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans RM. The steroid and thyroid hormone receptor superfamily. Science. 1988;240:889–895. doi: 10.1126/science.3283939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar V, Green S, Stack G, et al. Functional domains of the human estrogen receptor. Cell. 1987;51:941–951. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90581-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponglikitmongkol M, Green S, Chambon P. Genomic organization of the human oestrogen receptor gene. EMBO J. 1988;7:3385–3388. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb03211.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enmark E, Pelto-Huikko M, Grandien K, et al. Human estrogen receptor-β gene structure, chromosomal localization and expression pattern. J Clin Endocrinol Metabol . 1997;82:4258–4265. doi: 10.1210/jcem.82.12.4470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibata H, Spencer TE, Onate SA, et al. Role of co alphactivators and co-repressors in the mechanism of steroid/thyroid receptor action. Rec Prog Horm Res. 1997;52:141–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy LC, Leygue E, Dotzlaw H, et al. Oestrogen receptor variants and mutations in human breast cancer. Ann Med . 1997;29:221–234. doi: 10.3109/07853899708999340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leygue E, Dotzlaw H, Hare H, Watson PH, Murphy LC. Expression of estrogen receptor beta variant mRNAs in human breast tumors [abstract]. . Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1997;46:48. [Google Scholar]

- Vladusic E, Hornby A, Guerra-Vladusic F, Lupu R. Expression of estrogen receptor-β messenger RNA variant in breast cancer. Cancer Res. 1998;58:210–214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu B, Leygue E, Dotzlaw H, et al. Estrogen receptor-beta mRNA variants in human and murine tissues. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1998;138:199–203. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(98)00050-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore J, McKee D, Slentz-Kesler K, et al. Cloning and characterization of human estrogen receptor-β isoforms. . Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;247:75–78. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.8738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Miksicek RJ. Identification of a dominant negative form of the human estrogen receptor. Mol Endocrinol. 1991;5:1707–1715. doi: 10.1210/mend-5-11-1707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai A, Luqmani Y, Walters JE, et al. Presence of exon 5 deleted oestrogen receptor in human breast cancer: functional analysis and clinical significance. Br J Cancer . 1997;75:1173–1184. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1997.202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuqua SAW, Fitzgerald SD, Chamness GC, et al. Variant human breast tumor estrogen receptor with constitutive transcriptional activity. Cancer Res. 1991;51:105–109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaidarun S, Alexander J. A tumor specific truncated estrogen receptor splice variant enhances estrogen stimulated gene expression. . Mol Endocrinol. 1998;12:1355–1366. doi: 10.1210/mend.12.9.0170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dotzlaw H, Alkhalaf M, Murphy LC. Characterization of estrogen receptor variant mRNAs from human breast cancers. Mol Endocrinol . 1992;6:773–785. doi: 10.1210/mend.6.5.1603086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leygue ER, Watson PH, Murphy LC. Estrogen receptor variants in normal human mammary tissue. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1996;88:284–290. doi: 10.1093/jnci/88.5.284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leygue E, Murphy LC, Kuttenn F, Watson PH. Triple primer polymerase chain reaction: a new way to quantify truncated mRNA expression. . Am J Pathol. 1996;148:1097–1103. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erenburg I, Schachter B, Lopez RM, Ossowski L. Loss of an estrogen receptor isoform (ER alpha deleted 3) in breast cancer and the consequences of its reexpression: interference with estrogen-stimulated properties of malignant transformation. Mol Endocrinol. 1997;11:2004–2015. doi: 10.1210/mend.11.13.0031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiller T, Snell L, Watson PH. Microdissection/RT-PCR analysis of gene expression. Biotechniques. 1996;21:38–44. doi: 10.2144/96211bm07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy LC, Dotzlaw H. Variant estrogen receptor mRNA species detected in human breast cancer biopsy samples. Mol Endocrinol. 1989;3:687–693. doi: 10.1210/mend-3-4-687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elston CW, Ellis IO. Pathological prognostic factors in breast cancer. Histopathology. 1991;19:403–410. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1991.tb00229.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leygue E, Hall RE, Dotzlaw H, Watson PH, Murphy LC. Estrogen receptor variant mRNA expression in primary human breast tumors and matched lymph node metastases. . Br J Cancer. 1999;79:978–983. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daffada AA, Johnston SR, Smith IE, et al. Exon 5 deletion variant estrogen receptor messenger RNA expression in relation to tamoxifen resistance and progesterone receptor/pS2 status in human breast cancer. Cancer Res. 1995;55:288–293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy LC, Hilsenbeck SG, Dotzlaw H, Fuqua SAW. Relationship of clone 4 estrogen receptor variant messenger RNA expression to some known prognostic variables in human breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 1995;1:155–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire WL, Chamness GC, Fuqua SAW. Abnormal estrogen receptor in clinical breast cancer. J Ster Bioch Mol Biol. 1992;43:243–247. doi: 10.1016/0960-0760(92)90214-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaidarun SS, Klibanski A, Alexander JM. Tumor specific expression of alternatively spliced estrogen receptor messenger ribonucleic acid variants in human pituitary adenomas. J Clin Endocrinol Metab . 1997;82:1058–1065. doi: 10.1210/jcem.82.4.3864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villa E, Dugani A, Fantoni E, et al. Type of estrogen receptor determines response to antiestrogen therapy. Cancer Res . 1996;56:3883–3885. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klotz DM, Castles CG, Fuqua SAW, Spriggs LL, Hill SM. Differential expression of wild-type and variant ER mRNAs by stocks of MCF-7 breast cancer cells may account for differences in estrogen responsiveness. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1995;2:609–615. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.1702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rea D, Parker MG. Effects of an exon 5 variant of the estrogen receptor in MCF-7 breast cancer cells. . Cancer Res. 1996;56:1556–1563. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madsen MW, Reiter BE, Larsen SS, Briand P, Lykkesfeldt AE. Estrogen receptor messenger RNA splice variants are not involved in antiestrogen resistance in sublines of MCF-7 human breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 1997;57:585–589. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada K, Ichii S, Hatada T, Ishii H, Utsunomiya J. Comparison of variant expression of estrogen receptor mRNA in normal breast tissue and breast cancer. Int J Oncol. 1998;12:1025–1028. doi: 10.3892/ijo.12.5.1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]