Abstract

It is well established that Ca2+ plays a key role in promoting the physiological depolarization-induced release (DIR) of neurotransmitters from nerve terminals (Ca2+ hypothesis). Yet, evidence has accumulated for the Ca2+-voltage hypothesis, which states that not only is Ca2+ required, but membrane potential as such also plays a pivotal role in promoting DIR. An essential aspect of the Ca2+-voltage hypothesis is that it is depolarization that is responsible for the initiation of release. This assertion seems to be contradicted by recent experiments wherein release was triggered by high concentrations of intracellular Ca2+ in the absence of depolarization [calcium-induced release (CIR)]. Here we show that there is no contradiction between CIR and the Ca2+-voltage hypothesis. Rather, CIR can be looked at as a manifestation of spontaneous release under conditions of high intracellular Ca2+ concentration. Spontaneous release in turn is governed by a subset of the molecular scheme for DIR, under conditions of no depolarization. Prevailing estimates for the intracellular calcium concentration, [Ca2+]i, in physiological DIR rely on experiments under conditions of CIR. Our theory suggests that these estimates are too high, because depolarization is absent in these experiments and [Ca2+]i is held at high levels for an extended period.

The essential role of Ca2+ in promoting physiological depolarization-induced release (DIR) of neurotransmitters from nerve terminals is well established and needs no further confirmation. Indeed, the calcium hypothesis holds that intracellular elevation of Ca2+ is both necessary and sufficient to induce release. Yet, there is considerable evidence for the role of depolarization per se in promoting release (1–4), based on which the calcium-voltage hypothesis was suggested. Accordingly, under physiological conditions of DIR, Ca2+ is indeed necessary but membrane potential plays the pivotal role in release (5). In particular, we proposed that presynaptic inhibitory autoreceptors, in addition to their known role in feedback inhibition (6), are also the vehicle by which membrane potential controls initiation and termination of release. As a molecular mechanism for the calcium-voltage hypothesis we suggested that under rest conditions the release machinery is subject to a tonic block, which is attained by the association of the ligand-occupied inhibitory autoreceptor (which mediates feedback inhibition of transmitter release) with proteins of the exocytotic machinery. Initiation of release is achieved upon depolarization by relief from the tonic block; when this block is reinstated upon membrane repolarization, termination of release occurs (5).

The hypothesized molecular mechanism for release control was tested for one major neurotransmitter, acetylcholine (ACh), for which the relevant inhibitory autoreceptor is the M2 muscarinic ACh receptor (M2R). In particular, the idea that, at rest, the release machinery is tonically blocked is supported by the finding that release of ACh was enhanced by antagonists of M2R (7–9). The hypothesis that this block is achieved by the association of M2R with proteins of the exocytotic machinery is supported by findings in rat brain synaptosomes that M2R coprecipitates with synaptotagmin and with SNARE proteins [syntaxin, 25-kDa synaptosomal-associated protein (SNAP25), and a vesicle-associated membrane protein (VAMP/synaptobrevin)]. Moreover, it was found that this association takes place only if M2R is bound to ACh or a muscarinic receptor agonist, and that this association is strong at resting potential, but it becomes weaker under depolarization. It was further shown that M2R has two states, of high and low affinity, and membrane protential controls the distribution between the two states (10, 11). Based on the above experiments, a molecular scheme and corresponding mathematical model for DIR were developed (12).

A direct confirmation of the key role that the M2R autoreceptor plays in the control of the time course of ACh release was obtained from the following experiment. If binding of ACh to M2R is retarded (by addition of a specific M2/M4 receptor antagonist, or of exogenous acetylcholinesterase, then the time course of ACh release is prolonged (13). Further confirmation came from knockout mice lacking functional M2R (26). For these mice, elevation of intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) increased the duration of ACh release, whereas release was shortened by more rapid removal of [Ca2+]i through the addition of a fast calcium chelator. These results contrast with the behavior of wild-type mice and other preparations, where release kinetics are insensitive to [Ca2+]i or its kinetics (14–16).

In addition to the findings concerning M2R, partial evidence for the proposed mechanism for release control also exists (L. Ohanna, I. Parnas, and H.P., unpublished data) for the metabotropic glutamate receptor MGluR3 that mediates feedback inhibition of glutamate release (17).

Despite all of this supportive evidence, the idea that membrane potential has a major role in controlling release seems to be contradicted by recent experiments where release was induced by Ca2+ alone, without concomitant depolarization [calcium-induced release (CIR)]. In these experiments release (of glutamate) was induced by an abrupt elevation of [Ca2+]i by flash photolysis of a caged Ca2+ compound, while the membrane potential was maintained at rest (18–20). Here we suggest a way to reconcile the conflicting evidence. We show that CIR can be directly derived from the molecular scheme describing DIR. In particular, we note that a mechanism for spontaneous release is a subset of the scheme for DIR. We suggest that CIR may be looked at as a manifestation of spontaneous release under conditions of high [Ca2+]i.

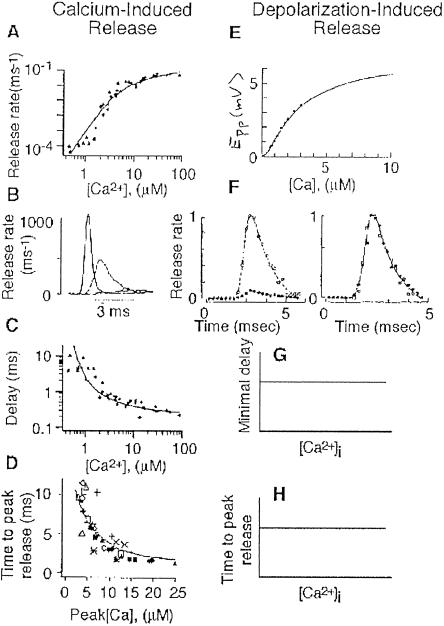

Dependence on [Ca2+]i of CIR and DIR: Experimental Results

Fig. 1A shows that the release rate (analogous to the quantal content) of CIR increases in a sigmoid manner as [Ca2+]i increases. The slope on a log–log plot of release rate vs. [Ca2+]i was estimated to be ≈4 (19). It is further shown that for CIR, the overall time course of release (Fig. 1B), as well as specific facets of the time course [the delay between the stimulus and the onset of release, i.e., the minimal delay (Fig. 1C), and the time-to-peak release (Fig. 1D)] are sensitive to [Ca2+]i.

Fig 1.

Experimental results obtained for CIR and DIR from refs. 15 and 19–21 with permission. (A–D) CIR in the calyx of Held from rats. (A) Dependence of the rate of release on [Ca2+]i (19). [Reproduced with permission from ref. 19 (Copyright 2000, AAAS, www.sciencemag.org).] (B) Time course of release at three levels of [Ca2+]i (20). [Reproduced with permission from ref. 20 (Copyright 2000, MacMillan Magazines, Ltd., www.nature.com).] (C) Dependence of the minimal delay on [Ca2+]i (19). [Reproduced with permission from ref. 19 (Copyright 2000, AAAS, www.sciencemag.org).] (D) Dependence of the time to peak release on [Ca2+]i (20). [Reproduced with permission from ref. 20 (Copyright 2000, MacMillan Magazines, Ltd., www.nature.com).] (E–H) DIR. (E) Dependence of the quantal content, expressed as E.p.p. (end plate potential), on extracellular Ca2+ concentration, [Ca2+]0 (21). [Reproduced with permission from ref. 21 (Copyright 1967, The Physiological Society).] (F) Time course of release at two levels of [Ca2+]0 (normalized time course is seen on the right) (15). [Reproduced with permission from ref. 15 (Copyright 1980, The Physiological Society).] (G and H) Schematic drawings of the dependence on [Ca2+]i of the minimal delay and time-to-peak release in DIR; see text.

When release is induced by the physiological stimulus, i.e., in DIR, the relation between the quantal content and [Ca2+]i is similar to the relation between release rate and [Ca2+]i in CIR. (Compare Fig. 1 E and A.) Again, the slope of a log–log plot is ≈4 (21). In sharp contrast with the behavior of CIR, here the time course of release is invariant to experimental manipulations that change [Ca2+]i (Fig. 1F; also see refs. 14 and 22) or its kinetics (16). A schematic summary of these experimental results for DIR is shown in Fig. 1 G and H, where it is seen that neither the minimal delay (Fig. 1G), nor the time to peak release (Fig. 1H) is affected by such experimental manipulations.

With respect to their dependence on [Ca2+]i, the two modes of release thus exhibit similar behavior as far as the quantal content is concerned, but differ fundamentally in the behavior of their time courses.

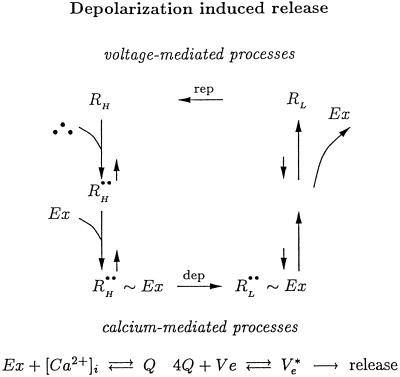

Molecular Level Model for DIR

As we wish to show that the behavior of CIR can be derived from our molecular scheme (12) for control of DIR, we present the essence of this scheme (including only key states and steps) in Fig. 2. (Full details of the scheme are published as supporting information on the PNAS web site, www.pnas.org). At resting potential (Fig. 2, left) the receptor is in a high-affinity state (RH). Hence, even though the tonic concentration of transmitter in the synaptic cleft is low, a large fraction of the autoreceptors will be occupied by transmitter (•), yielding R . These bound autoreceptors, but not unbound autoreceptors, interact physically with proteins of the exocytotic machinery (Ex) to form the complex R

. These bound autoreceptors, but not unbound autoreceptors, interact physically with proteins of the exocytotic machinery (Ex) to form the complex R ∼ Ex. As a result, under rest conditions the release machinery is maintained in a tonically blocked state mediated by the inhibitory autoreceptor.

∼ Ex. As a result, under rest conditions the release machinery is maintained in a tonically blocked state mediated by the inhibitory autoreceptor.

Fig 2.

Simplified kinetic scheme for DIR (12). RH denotes the high-affinity- and RL the low-affinity receptor. The state of association between the receptor bound with two molecules of agonist, R••, and the exocytotic machinery, Ex, is denoted by R ∼ Ex. Depolarization and repolarization are denoted by dep and rep.

∼ Ex. Depolarization and repolarization are denoted by dep and rep.

Release initiation occurs when depolarization rapidly shifts the autoreceptor to a low-affinity state (RL). Consequently, transmitter detaches from the autoreceptor, which then no longer associates with Ex (Fig. 2, right). The free, unblocked, Ex acts together with Ca2+, which entered through voltage-gated Ca2+ channels, to induce release (Fig. 2, Lower).

Release termination occurs when repolarization reverses the initiation process. Receptor switches back from low affinity to high affinity (Fig. 2, Upper), transmitter rebinds to receptor, bound receptor reassociates with the release machinery, and the block is reinstated.

The lowest part of Fig. 2 summarizes Ca2+-mediated processes, the action of Ex with the entered Ca2+ to promote release. The mechanism for the joint action of Ca2+ and Ex is formulated phenomenologically as in refs. 12 and 23. A mass-action term for binding of Ca2+ and Ex produces a complex Q. The cooperative action of four Q complexes with a vesicle Ve activates Ve (giving Ve*) and leads to release.

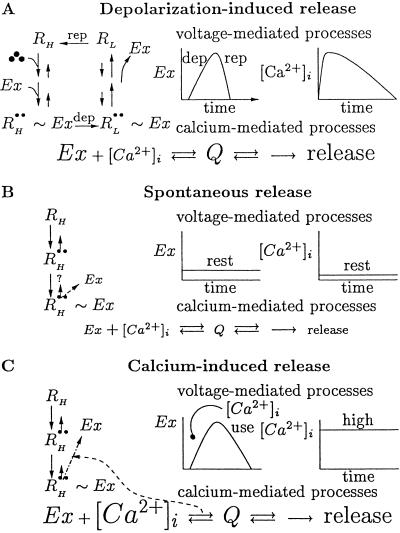

Spontaneous Release and CIR as Subsets of DIR

Summarized pictorially in Fig. 3 is our argument that CIR can be derived from DIR, as a manifestation of spontaneous release. Fig. 3A depicts the processes that govern DIR together with a schematic presentation of the kinetics of key variables in the release process, Ex and [Ca2+]i. On the left, the molecular scheme shown in Fig. 2 is recapitulated. From this scheme it follows that the kinetics of Ex (Center) is governed by membrane potential: depolarization frees Ex and repolarization causes the reassociation of Ex to the receptor. On the right, the kinetics of [Ca2+]i is seen. [Ca2+]i accumulates as a result of the depolarization-mediated opening of Ca2+ channels and declines as a result of the diffusion of Ca2+ away from the release sites, buffering, and extrusion of Ca2+. Potentially, the kinetics of the release process could be determined by the kinetics of Ex, by that of [Ca2+]i, or by a combination of the two. The observation that the kinetics of DIR is independent of the Ca2+ level (Fig. 1F; refs. 14, 15, and 22) suggests that the influx and accumulation of [Ca2+]i is faster than the freeing of Ex from the high-affinity autoreceptor RH (when depolarization induces the transition RH → RL), and that the removal of Ca2+ is slower than the recapturing of Ex by the high-affinity autoreceptor RH (compare Fig. 3A, Center and Right). Under such circumstances both initiation and termination of release will depend only on the kinetics of Ex, which in DIR depends only on membrane potential. As mentioned before, the free Ex acts with [Ca2+]i to promote release through calcium-mediated processes.

Fig 3.

Outline of the processes that mediate the three types of release. (A) DIR. (Left) Molecular scheme of Fig. 2. (Center) Membrane-potential-dependent Ex kinetics. (Right) Kinetics of [Ca2+]i-depolarization-mediated influx and membrane-potential-independent removal. (B) Spontaneous release. (Left) Part of the scheme of Fig. 2 that remains under resting potential. A question mark symbolizes spontaneous dissociation of Ex from R Ex. (Center and Right) Low steady-state values of Ex and [Ca2+]i. The low values are symbolized by small letters in calcium-mediated processes for forming Ex. (C) CIR. (Left) As in B but with a higher rate of forming Ex (symbolized by a larger dotted-dashed arrow), owing to a large [Ca2+]i (symbolized by large letters). (Center) Ca2+-dependent kinetics of free Ex. (Right) Fixed high level of [Ca2+]i. Note that the calcium-mediated processes are common to all three modes of release. For details, see text.

Ex. (Center and Right) Low steady-state values of Ex and [Ca2+]i. The low values are symbolized by small letters in calcium-mediated processes for forming Ex. (C) CIR. (Left) As in B but with a higher rate of forming Ex (symbolized by a larger dotted-dashed arrow), owing to a large [Ca2+]i (symbolized by large letters). (Center) Ca2+-dependent kinetics of free Ex. (Right) Fixed high level of [Ca2+]i. Note that the calcium-mediated processes are common to all three modes of release. For details, see text.

Spontaneous release occurs at resting potential. In the absence of depolarization, only the left arm remains from the entire scheme of Fig. 2 (Fig. 3B Left). At rest, [Ca2+]i remains low, because without depolarization no calcium influx takes place. In addition, at rest the system resides mainly in R ∼ Ex. From this state only rare spontaneous excursions (symbolized by a question mark in Fig. 3B Left) occasionally permit a release event by freeing Ex from its association with R

∼ Ex. From this state only rare spontaneous excursions (symbolized by a question mark in Fig. 3B Left) occasionally permit a release event by freeing Ex from its association with R . Thus, the rate of spontaneous release is expected to be low. Note that the calcium-mediated processes are common to both DIR and spontaneous release.

. Thus, the rate of spontaneous release is expected to be low. Note that the calcium-mediated processes are common to both DIR and spontaneous release.

Fig. 3B implies a possible mechanism for CIR. Because [Ca2+]i during spontaneous release, the reaction Ex + [Ca2+]i ⇄ Q maintains an equilibrium between R ∼ Ex and Ex such that only rarely is Ex spontaneously freed from its association with R

∼ Ex and Ex such that only rarely is Ex spontaneously freed from its association with R . Suppose, however, that [Ca2+]i is abruptly increased to high concentrations. The high [Ca2+]i then shifts the quasi-equilibrium of the reaction R

. Suppose, however, that [Ca2+]i is abruptly increased to high concentrations. The high [Ca2+]i then shifts the quasi-equilibrium of the reaction R ∼ Ex ⇄ R

∼ Ex ⇄ R + Ex toward large free Ex. See Fig. 3C. There is an irreversible depletion of Ex by the release process, but the quasi-equilibrium is maintained by the continuous replenishment of Ex from R

+ Ex toward large free Ex. See Fig. 3C. There is an irreversible depletion of Ex by the release process, but the quasi-equilibrium is maintained by the continuous replenishment of Ex from R ∼ Ex until R

∼ Ex until R ∼ Ex is exhausted.

∼ Ex is exhausted.

In CIR, Ex disappears by “use” when vesicles bound to the Ex-[Ca2+]i complex Q are released. The use, in turn, is governed only by the calcium-mediated processes, i.e., by [Ca2+]i. (Recall that in DIR, Ex disappeared because of repolarization-mediated recapturing of Ex by R .) As is the case for DIR, here too, release requires the joint action of Ex and [Ca2+]i (Fig. 3, calcium-mediated processes). Here, however, the concentration of [Ca2+]i is fixed (Fig. 3C Right), so that it is again the kinetics of Ex (Fig. 3C Center) that determines the time course of release.

.) As is the case for DIR, here too, release requires the joint action of Ex and [Ca2+]i (Fig. 3, calcium-mediated processes). Here, however, the concentration of [Ca2+]i is fixed (Fig. 3C Right), so that it is again the kinetics of Ex (Fig. 3C Center) that determines the time course of release.

Let us recapitulate some salient points. Both in CIR and in DIR, it is the kinetics of Ex that determines the time course of transmitter release. But, in DIR, the kinetics of Ex is determined by membrane potential, and in CIR it is determined by [Ca2+]i. More precisely, freeing of Ex from its association with the high-affinity receptor is achieved in CIR by [Ca2+]i and in DIR by depolarization. Furthermore, disappearance of Ex is achieved in CIR by [Ca2+]i-dependent use, and in DIR by membrane repolarization. Because only in CIR is the time course of the controlling factor Ex determined by [Ca2+]i, it follows that only in CIR is the time course of release expected to depend on [Ca2+]i.

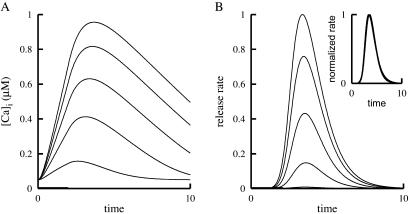

Simulation Results

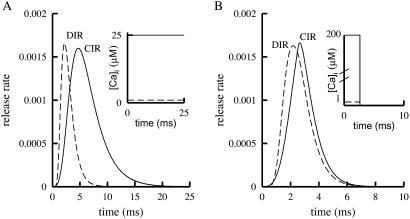

We now present simulation results that demonstrate, in a more quantitative fashion, our qualitative assertions concerning CIR and DIR. To obtain CIR, the complete model (see supporting information) was simulated with [Ca2+]i kept fixed at a constant level, and with transmitter concentration fixed at its rest level. No depolarization was applied. With rate constants that were mainly fixed to account for DIR, the simulations in Fig. 4A show that synchronous releases of increasing magnitudes are obtained at increasing levels of [Ca2+]i (Fig. 4A Inset). The time to peak release declines as [Ca2+]i increases, and release terminates faster at higher [Ca2+]i. Also a double logarithmic plot of peak rate of release vs. [Ca2+]i provides a slope (Hill coefficient) of ≈3 (not shown).

Fig 4.

Simulation of CIR (see supporting information) at various levels of [Ca2+]i. The maximum release rate increases with [Ca2+]i whereas Ex and R ∼ Ex decrease with [Ca2+]i. (A) Time course of release at various levels of [Ca2+]i (Inset). (B–D) Time courses of intermediate states that govern A: Ve(B), Ex(C), and Q(D).

∼ Ex decrease with [Ca2+]i. (A) Time course of release at various levels of [Ca2+]i (Inset). (B–D) Time courses of intermediate states that govern A: Ve(B), Ex(C), and Q(D).

To quantify the mechanism that underlies the simulation results of Fig. 4A, we show the kinetic behavior of the most relevant states, the vesicles (Fig. 4B), Ex (Fig. 4C), and the complex of bound receptor and Ex (R ∼ Ex) (Fig. 4D). It is seen in Fig. 4D that the higher [Ca2+]i, the lower the occupancy of the state R

∼ Ex) (Fig. 4D). It is seen in Fig. 4D that the higher [Ca2+]i, the lower the occupancy of the state R ∼ Ex. Correspondingly, higher Q is obtained (not shown) because more Ex is freed from R

∼ Ex. Correspondingly, higher Q is obtained (not shown) because more Ex is freed from R ∼ Ex. The behavior of free Ex is more complex (Fig. 4C). At resting potential the (initial) level of free Ex is very low. (Initially, Ex has the low value of 0.06 because most Ex is bound to R

∼ Ex. The behavior of free Ex is more complex (Fig. 4C). At resting potential the (initial) level of free Ex is very low. (Initially, Ex has the low value of 0.06 because most Ex is bound to R ; the total Ex concentration is normalized to unity.) This level drops further when [Ca2+]i is elevated, and the initial drop is greater the higher the [Ca2+]i. The drop occurs because Ex binds to Ca2+ to form the complex Q. Later, there is an increase of Ex (which depends on [Ca2+]i) in accord with the balance between the “source,” R

; the total Ex concentration is normalized to unity.) This level drops further when [Ca2+]i is elevated, and the initial drop is greater the higher the [Ca2+]i. The drop occurs because Ex binds to Ca2+ to form the complex Q. Later, there is an increase of Ex (which depends on [Ca2+]i) in accord with the balance between the “source,” R ∼ Ex, and the “sink,” the formation of Q. If the vesicle supply were unlimited, the source R

∼ Ex, and the “sink,” the formation of Q. If the vesicle supply were unlimited, the source R ∼ Ex would then become exhausted and the resulting disappearance of Ex would terminate release. In the simulations of Fig. 4, vesicle depletion is rather rapid (Fig. 4B), and this depletion terminates release.

∼ Ex would then become exhausted and the resulting disappearance of Ex would terminate release. In the simulations of Fig. 4, vesicle depletion is rather rapid (Fig. 4B), and this depletion terminates release.

Comparison of the simulation results to experiments of CIR shows that all of the qualitative experimental behaviors (illustrated in Fig. 1; see also refs. 18–20) are captured by the simulations of CIR. In particular, the simulation results of Fig. 4A depict sensitivity to [Ca2+]i of the time course of release; at higher values of [Ca2+]i the time to peak is shorter and the decay is faster. The value of the Hill coefficient is ≈3 (not shown), in the same range as that found experimentally (19). It seems that vesicle depletion, of even stronger magnitude than that of our simulations, is responsible for the rapid termination of release in the experiments shown in Fig. 1B.

For comparison, Fig. 5 shows simulation results of DIR. The same molecular scheme with the same set of parameters as for CIR was used, but a depolarizing pulse was then given. For DIR, the physiological mode of release, we naturally took into account Ca2+ influx and removal, as in earlier studies (12, 23). The transmitter was kept fixed at its initial concentration, because it has been shown experimentally and theoretically (13, 24) that the time course of DIR is not affected by variations in transmitter concentration. The resulting profiles of [Ca2+]i are shown in Fig. 5A. Fig. 5B depicts the corresponding release time courses. The normalized curves (Fig. 5B Inset) show that, as for the experiments (14, 15, 22) and in contrast to CIR, the time course of DIR is insensitive to [Ca2+]i in spite of its variation. The two modes of release do, however, have behavior in common with respect to the dependence of the quantal content on [Ca2+]i. Similarly to CIR, the quantal content shows a sigmoid dependence on [Ca2+]i with a Hill coefficient of ≈3 (not shown).

Fig 5.

Simulations of DIR with the same model as for CIR. The thick bars in the time axis represent the 2-ms duration of a high depolarizing pulse, in the range of an action potential. (A) Time course of [Ca2+]i obtained by solving the equations presented in ref. 23). See supporting information. (B) Time course of release that corresponds to the [Ca2+]i profiles seen in A. Higher [Ca2+]i corresponds to higher release rate. (Inset) Each graph is normalized to its own peak.

Discussion

This paper attempts to reconcile theories concerning the controlling role of membrane potential in physiological DIR with recent experiments that show CIR in the absence of depolarization. The core of our argument rests on the assumption that all three modes of release: spontaneous release, DIR, and CIR, are controlled by the same inhibitory autoreceptor, which is obviously different for different transmitters. The three modes of release are of course realized under different conditions: spontaneous release under conditions of rest (low[Ca2+]i and no depolarization), DIR under physiological conditions of depolarization, and CIR under experimental conditions where there is no depolarization and [Ca2+]i is artificially raised. In particular, we have argued that spontaneous release is a subset of DIR. Evidence for this assertion is the finding that spontaneous release is modulated by the same inhibitory autoreceptor that controls DIR: in cholinergic synapses, the addition of antagonists of M2R (the inhibitory autoreceptor in such synapses) increased both evoked and spontaneous ACh release. Similarly, an agonist of this receptor inhibited both evoked and spontaneous release (6).

Release kinetics are observed to depend on [Ca2+]i in CIR but not in DIR (Fig. 1). We suggested above that the insensitivity to [Ca2+]i in DIR occurs because [Ca2+]i enters rapidly and declines slowly, thereby leaving kinetic control to the relatively slow action of depolarization in its freeing of Ex and the relatively fast action of repolarization in recapturing free Ex. Indeed, these suggestions concerning the relative speeds of [Ca2+]i kinetics and free Ex kinetics have recently been validated in knockout mice lacking functional M2R (26). For these mice, ACh release began sooner and lasted longer, compared with wild-type mice.

To explain the sensitivity to [Ca2+]i of CIR, we note that in CIR [Ca2+]i plays two roles. There is a common role involving the calcium-mediated processes that is the same in both CIR and DIR, and also in spontaneous release (Fig. 3). There is also an additional role in CIR, the same role that depolarization plays in DIR, that of freeing the exocytotic machinery from its association with the high-affinity receptor. Hence, because Ca2+ is the only controlling factor in CIR, then release kinetics must be sensitive to [Ca2+]i. Such sensitivity has indeed been found in the experiments shown in Fig. 1 B–D, and also in mice lacking functional M2R (26).

It could be argued that the CIR can be explained by some variation of the calcium hypothesis. Indeed it was shown by Schneggenburger and Neher (20) that their experiments were consistent with a straightforward version of the calcium hypothesis. Nonetheless, this conclusion does not negate our central point that the CIR experiments are fully consistent with the calcium-voltage hypothesis.

Because of the additional role that [Ca2+]i plays in CIR, it is expected that higher [Ca2+]i will be needed to produce an equal amount of release in the case of CIR compared with DIR. The reason is that had the [Ca2+]i needed for the common role also been sufficient to free Ex, then this role would also have been carried out by Ca2+ under the physiological DIR. If this indeed were the case, then the time course of DIR would be sensitive to [Ca2+]i exactly as is CIR, which it is not (Fig. 1; refs. 14–16 and 22).

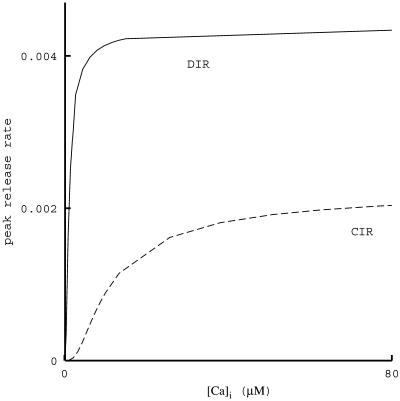

Fig. 6 shows simulation results confirming indeed that higher [Ca2+]i is needed in CIR than in DIR. As seen in Fig. 6A, to obtain the same peak release, [Ca2+]i of 25 μM was needed in CIR and only 1 μM was needed in DIR. In Fig. 6A, similarly to the experiments described in refs. 18–20, [Ca2+]i remained elevated at a fixed level for tens of milliseconds. However, under physiological conditions, the elevation of [Ca2+]i, at least in the vicinity of the release sites, is believed to be brief, in the range of a few milliseconds (25). If [Ca2+]i remains elevated for only a brief time, it is expected (owing to the relatively small rate constant that characterizes the dissociation of R ∼ Ex to Ex through the left arm in Fig. 2) that in CIR, even higher [Ca2+]i will be needed to produce an amount of release equal to that of DIR. The simulations depicted in Fig. 6B show that in this case, 200 μM [Ca2+]i is needed to obtain through CIR the same peak release as that obtained in DIR with 1 μM [Ca2+]i.

∼ Ex to Ex through the left arm in Fig. 2) that in CIR, even higher [Ca2+]i will be needed to produce an amount of release equal to that of DIR. The simulations depicted in Fig. 6B show that in this case, 200 μM [Ca2+]i is needed to obtain through CIR the same peak release as that obtained in DIR with 1 μM [Ca2+]i.

Fig 6.

Levels of [Ca2+]i required to obtain the same peak release in simulations of CIR and DIR. (A) Solid line shows CIR, at high [Ca2+]i; the level of [Ca2+]i is fixed throughout the simulation (Inset). Dashed line shows DIR, of comparable magnitude, at low [Ca2+]i. (B) Descriptions are the same as in A, except that [Ca2+]i is elevated only briefly.

The levels of [Ca2+]i needed for physiological DIR were estimated to range from tens (19, 20) to hundreds (18) of μM. The simulation results of Fig. 6 indicate that these are overestimates. We suggest that the estimates are too high because these authors assessed the needed level of [Ca2+]i in DIR from experiments done in CIR, where depolarization is absent and the elevation of [Ca2+]i is prolonged. Equivalently, the affinity of the putative Ca2+ sensor may well be much higher than was concluded from experiments with CIR. In these experiments, the Kd of the Ca2+ sensor was estimated to be 194 μM (18), or ≈25 μM (20). In contrast, in DIR the Kd was estimated to be 2–4 μM (22). Simulation results for estimating Kd from CIR and DIR are shown in Fig. 7. Peak release rates, such as those seen in Figs. 4 and 5, are plotted for CIR and DIR when [Ca2+]i is fixed at different levels for long durations, tens of milliseconds. It is clearly seen that DIR approaches saturation at much lower [Ca2+]i than does CIR. Furthermore, these simulations yield Kd = 69 μM for CIR and Kd = 1.6 μM for DIR. As anticipated, the former is indeed much larger than the latter. Moreover, even though no parameter adjustments were made, the actual simulation values of Kd are in the range of the values obtained in the experiments cited above.

Fig 7.

Dependence of peak release rate on long pulses of [Ca2+]i for CIR and DIR. To obtain Kd, simulation results were fit to the Hill equation [Ca2+] /K

/K + [Ca2+]

+ [Ca2+] . For DIR, similar results are obtained when [Ca2+]i is maintained at a constant level for 2 ms or for tens of milliseconds.

. For DIR, similar results are obtained when [Ca2+]i is maintained at a constant level for 2 ms or for tens of milliseconds.

In addition to the experiments already described, how could our theory be challenged further? The most direct new experiment to test our hypothesis for CIR would be to add agonists of the relevant inhibitory autoreceptor and examine their effect on the time course of CIR. Such agonists are not expected to affect the time course of DIR, and indeed, they do not (13). Fig. 2 suggests that in the presence of high levels of such agonists, the rate of freeing Ex from R ∼ Ex, through the left arm, will be hindered; the equilibrium will be shifted toward formation of RH ∼ Ex, and hence the rate of CIR is predicted to decrease. Thus, the time course of CIR, unlike that of DIR, should depend on transmitter kinetics. For quantitative prediction of release kinetics in experiments that would show such dependence, our model would have to be expanded to take into account variation in transmitter concentration.

∼ Ex, through the left arm, will be hindered; the equilibrium will be shifted toward formation of RH ∼ Ex, and hence the rate of CIR is predicted to decrease. Thus, the time course of CIR, unlike that of DIR, should depend on transmitter kinetics. For quantitative prediction of release kinetics in experiments that would show such dependence, our model would have to be expanded to take into account variation in transmitter concentration.

We showed here that there is no contradiction between the calcium-voltage hypothesis (for DIR) and the calcium hypothesis (for CIR). Each of the two modes of release may prevail under different circumstances. DIR occurs under physiological conditions in fast releasing systems. DIR is controlled by two factors: membrane potential and [Ca2+]i, and membrane potential determines the time course. This result ensures that the time course will be the same under different conditions such as repetitive stimulation or other modulations of [Ca2+]i. Because release is so brief its time course should be reliable. In slow systems, where release can last from hundreds of milliseconds to minutes, it may well be that CIR occurs. In slow release, precision is presumably not critical so that a simpler release control mechanism based on one factor, [Ca2+]i, may be appropriate.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

J.-C.V.-L. was supported by the Women's International Zionist Organization (WIZO) (Uruguay) and the Program for the Development of Basic Sciences (PEDECIBA) (Uruguay).

Abbreviations

DIR, depolarization-induced release

CIR, calcium-induced release

ACh, acetylcholine

[Ca2+]i, intracellular Ca2+ concentration

References

- 1.Silinsky E. M., Watanabe, M., Redman, R. S., Qiu, R., Hirsh, J. K., Solsona, C. S., Alford, S. & Macdonald, R. C. (1995) J. Physiol. (London) 482, 511-520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mochida S., Yokoyama, C. T., Kim, D. K., Itoh, K. & Catterall, W. A. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 14523-14528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ravin P., Parnas, H., Spira, M. E. & Parnas, H. (1999) J. Neurophysiol. 81, 3044-3053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang C. & Zhou, Z. (2002) Nat. Neurosci. 5, 425-430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parnas H., Segel, L., Dudel, J. & Parnas, I. (2000) Trends Neurosci. 23, 47-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Slutsky I., Parnas, H. & Parnas, I. (1999) J. Physiol. (London) 514, 769-782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morita K., North, R. A. & Tokomasa, T. (1982) J. Physiol. (London) 333, 141-149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peteris A. & Ogren, V. R. (1988) J. Physiol. (London) 395, 441-453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wessler I. (1988) Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 10, 110-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Linial M., Ilouz, N. & Parnas, H. (1997) J. Physiol. (London) 504, 251-258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ilouz N., Branski, L., Parnis, J., Parnas, H. & Linial, M. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 29519-29528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yusim K., Parnas, H. & Segel, L. (1999) Bull. Math. Biol. 61, 701-725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Slutsky I., Silman, I., Parnas, H. & Parnas, I. (2001) J. Physiol. (London) 536, 717-725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Andreu R. & Barret, E. F. (1980) J. Physiol. (London) 308, 79-97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Datyner N. B. & Gage, P. W. (1980) J. Physiol. (London) 303, 299-314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hochner B., Parnas, H. & Parnas, I. (1991) Neurosci. Lett. 125, 215-218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bardley S. R., Marino, M., Rouse, S. T., Awad, H., Levey, A. L. & Conn, P. J. (2000) J. Neurosci. 20, 3085-3094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heidelberger R., Heinemann, C., Neher, E. & Matthews, G. (1994) Nature 371, 513-515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bollmann J. H., Sakmann, B. & Borst, J. G. G. (2000) Science 289, 953-957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schneggenburger R. & Neher, E. (2000) Nature 406, 889-893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dodge F. A. & Rahamimoff, R. (1967) J. Physiol. (London) 193, 419-432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ravin R., Parnas, H., Spira, M. E., Volfovsky, N. & Parnas, I. (1999) J. Neurophysiol. 81, 634-642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lustig C., Parnas, H. & Segel, L. A. (1990) J. Theor. Biol. 144, 225-248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yusim K., Parnas, H. & Segel, L. (2000) Bull. Math. Biol. 61, 717-757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yamada W. M. & Zucker, R. S. (1992) Biophys. J. 61, 671-682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Slutsky, I., Wess, J., Gomeza, A. J., Dudel, J., Parnas, I. & Parnas, H., J. Neurophysiol, in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.