Abstract

P2X3 and P2X2/3 receptors are highly localized on peripheral and central processes of sensory afferent nerves, and activation of these channels contributes to the pronociceptive effects of ATP. A-317491 is a novel non-nucleotide antagonist of P2X3 and P2X2/3 receptor activation. A-317491 potently blocked recombinant human and rat P2X3 and P2X2/3 receptor-mediated calcium flux (Ki = 22–92 nM) and was highly selective (IC50 >10 μM) over other P2 receptors and other neurotransmitter receptors, ion channels, and enzymes. A-317491 also blocked native P2X3 and P2X2/3 receptors in rat dorsal root ganglion neurons. Blockade of P2X3 containing channels was stereospecific because the R-enantiomer (A-317344) of A-317491 was significantly less active at P2X3 and P2X2/3 receptors. A-317491 dose-dependently (ED50 = 30 μmol/kg s.c.) reduced complete Freund's adjuvant-induced thermal hyperalgesia in the rat. A-317491 was most potent (ED50 = 10–15 μmol/kg s.c.) in attenuating both thermal hyperalgesia and mechanical allodynia after chronic nerve constriction injury. The R-enantiomer, A-317344, was inactive in these chronic pain models. Although active in chronic pain models, A-317491 was ineffective (ED50 >100 μmol/kg s.c.) in reducing nociception in animal models of acute pain, postoperative pain, and visceral pain. The present data indicate that a potent and selective antagonist of P2X3 and P2X2/3 receptors effectively reduces both nerve injury and chronic inflammatory nociception, but P2X3 and P2X2/3 receptor activation may not be a major mediator of acute, acute inflammatory, or visceral pain.

The cloning and characterization of the P2X3 receptor, a specific ATP-sensitive ligand-gated ion channel that is selectively localized on peripheral and central processes of sensory afferent neurons (1–3), has generated much interest in the role of this receptor in nociceptive signaling (4). The discovery of the P2X3 receptor has provided a putative mechanism for previous reports that ATP, released from sensory nerves (5), produces fast excitatory potentials in dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neurons (6). These actions appear to be physiologically relevant because iontophoretic application of ATP to human skin elicits pain (7) and exogenously applied ATP enhances pain sensations in a human blister base model (8).

The P2X3 receptor is natively expressed as a functional homomer and as a heteromultimeric combination with the P2X2 (P2X2/3) receptor (1, 2, 9). Both P2X3-containing channels are expressed on a high proportion of isolectin IB4-positive neurons in DRG (3, 10). These receptors share similar pharmacological profiles (11), but differ in their acute desensitization kinetics (10, 12). Immunohistochemical studies have shown that P2X3 receptor expression is up-regulated in DRG neurons and ipsilateral spinal cord after chronic constriction injury (CCI) of the sciatic nerve (13). Additionally, CCI results in a specific ectopic sensitivity to ATP that is not observed on contralateral (uninjured) nerves (14).

Recently, the phenotypic profile of P2X3 receptor gene-disrupted mice has been reported (15, 16). P2X3(−/−) mice are viable and show no overt behavioral perturbations. However, P2X3(−/−) mice show reduced pain-related behaviors in response to intraplantar ATP or formalin administration, and ATP-mediated rapidly desensitizing inward currents in DRG neurons are absent in these mice. Although these observations support a role for P2X3 receptor activation in pain, one group has reported a transient hyperalgesic response in P2X3(−/−) mice after the intraplantar administration of complete Freund's adjuvant (CFA) (16). The effects of P2X3 receptor gene disruption on visceral pain and other models of acute and chronic nociception have not been reported.

There are numerous studies demonstrating that P2 receptor agonists and antagonists modulate nociceptive behaviors in rodents (17). However, determination of the specific role of P2X3 receptor activation in different pain states has been hampered by the lack of useful receptor ligands for in vivo studies. Existing P2 receptor agonists nonselectively activate a variety of P2 receptor subtypes and are metabolically labile (18). P2 receptor antagonists such as suramin and pyridoxalphosphate-6-azophenyl-2′,4′-disulfonic acid lack high affinity and specificity for individual P2 receptor subtypes (18).

The present studies were undertaken to characterize the antinociceptive effects of A-317491 (Fig. 1A), the first non-nucleotide antagonist that has high affinity and selectivity for blocking P2X3 homomeric and P2X2/3 heteromeric channels. The chiral pure S-enantiomer, A-317491, was found to potently block P2X3 and P2X2/3 receptor-activated calcium flux in vitro. After s.c. administration, A-317491 dose-dependently reduced nociception in neuropathic and inflammatory animal pain models, but generally lacked acute analgesic efficacy. The R-enantiomer, A-317344, showed markedly less activity at P2X3 and P2X2/3 receptors in vitro and lacked antinociceptive effects in animal models.

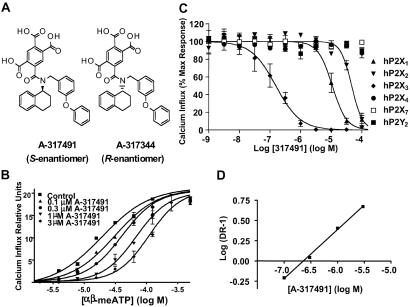

Fig 1.

(A) Structures of A-317491 and A-317344. (B) The selectivity of A-317491 to block activation of the human P2X3 receptor, as compared with other P2X receptor subtypes. Representative concentration-effect curves were normalized to the agonist response (percentage maximal response) in the absence of A-317491. See Tables 1 and 2 for agonist concentrations and derived Ki values. (C) Representative concentration-effect curves for α,β-meATP in the absence (control) and presence of increasing concentrations of A-317491. Data represent mean ± SEM from three separate experiments. (D) Schild plot.

Materials and Methods

Ca2+ Influx Assay.

Stably transfected 1321N1 human astrocytoma cells expressing rat and human P2X receptors have been described (9–11). Activation of human and rat recombinant P2X receptors was determined on the basis of agonist-induced increases in cytosolic Ca2+ concentration as described with minor modifications (11). The fluorescent Ca2+ chelating dye fluo-4 was used as an indicator of the relative levels of intracellular Ca2+ in a 96-well format by using a fluorescence imaging plate reader (Molecular Devices). P2X receptor-expressing cells were grown to confluence and plated in 96-well black-walled tissue culture plates ≈18 h before the experiment. One to two hours before the assay, cells were loaded with fluo-4 AM (2.28 μM; Molecular Probes) in Dulbecco's PBS (D-PBS) and maintained in a dark environment at room temperature. Immediately before the assay, each plate was washed twice with 250 μl D-PBS per well to remove extracellular fluo-4 AM. Two 50-μl additions of compounds (prepared in D-PBS) were made to the cells during each experiment. The first test compound (antagonist) addition was made, and incubation continued for 3 min before the addition of α,β-me-ATP (3 μM final concentration). Measurements continued for 3 min after this final addition. Fluorescence data were collected at 1- or 5-s intervals throughout the course of each experiment. Concentration–response data were analyzed by using graphpad prism (San Diego). Ki values were estimated by the equation: Ki = IC50/(1 + [agonist]/agonist EC50) (19).

Electrophysiology.

Whole-cell patch-clamp recordings were obtained as described (10) from stable cell lines or DRG neurons by using a modified extracellular saline consisting of 155 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 2 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 10 mM Hepes, 12 mM glucose, pH 7.4. The patch pipette solution consisted of 140 mM potassium aspartate, 20 mM NaCl, 10 mM EGTA, 5 mM Hepes. All cells were voltage-clamped at −60 mV, and series resistance was compensated 75–90% by using an Axopatch 200B amplifier (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA).

Rat DRG neurons were prepared as described (10). Lumbar (L4–6) DRG were dissected and placed in DMEM (HyClone) containing 0.3% collagenase B (Roche Molecular Biochemicals) for 60 min at 37°C. The collagenase was replaced with 0.25% trypsin (GIBCO/BRL) in Ca2+/Mg2+-free Dulbecco's PBS and further digested for 30 min at 37°C. Ganglia were washed in fresh DMEM, dissociated by trituration, and plated on polyethylenimine-treated coverslips. Cells were plated in 1 ml DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS (HyClone), nerve growth factor (50 ng/ml, Roche Molecular Biochemicals), and 100 units/ml penicillin/streptomycin.

Drugs were applied to the cells by using a piezoelectric-driven glass theta tube positioned near the cell. During experiments, agonists were usually applied every 3 min. A-317491 was both preapplied and coapplied to cells during agonist application. Responses were acquired and digitized at 3 kHz, and analyzed by using pclamp software (Axon Instruments). Current amplitudes were measured at the peak of the response.

Pharmacological Selectivity Studies.

The activity of A-317491 (10 μM) was evaluated in a number of assays to assess pharmacological selectivity relative to 86 other cell-surface receptors, ion channels, transport sites, and enzymes including the opioid receptor subtypes and cycloxygenases 1 and 2, by use of standardized assay protocols (Cerep, Celle l'Evescault, France) as described (20).

In Vivo Studies: Subjects.

In most experiments, male Sprague–Dawley rats (Charles River Breeding Laboratories) weighing 200–300 g were used. The abdominal constriction assay was conducted by using male 129J mice weighing 20–25 g (The Jackson Laboratories). The hotplate assay was conducted by using male CF-1 mice (Harlan Farms, Portage, MI) weighing 25–30 g. These animals were group-housed in American Association for the Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care-approved facilities at Abbott Laboratories in a temperature-regulated environment with lights on between 0700 and 2000 hours. Food and water was available ad libitum except during testing. All animal handling and experimental protocols were approved by an institutional animal care and use committee.

Analgesia and Side-Effect Assays.

A-317491 and A-317334 were evaluated in a number of well-characterized in vivo models to assess acute (noxious thermal, mechanical, and chemical stimulation), inflammatory (intraplantar formalin, carrageenan, and CFA), and neuropathic (CCI and L5/L6 nerve ligation) pain, as well as models of visceral (acetic acid-induced abdominal constriction, and normal and inflamed colonic distention) and postoperative pain (20–22). The specific methodologies for these nociceptive assays and the assessment of rat motor performance, hemodynamics, and general CNS function are described in detail in the Supporting Text, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site, www.pnas.org. Unless otherwise noted, all experimental and control groups contained at least six animals each, and data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Data analysis was conducted by using ANOVA and appropriate post hoc comparisons (P < 0.05) as described (20, 21). ED50 values were estimated by using least-squares linear regression.

Compounds.

A-317491 and A-317344 were synthesized at Abbott Laboratories. Compounds were dissolved in sterile water for s.c administration and administered in a final volume of 1–5 ml/kg, s.c. Except where noted, compounds were administered 30 min before nociceptive and side-effect testing.

Results

In Vitro Activities of A-317491.

ATP and α,β-meATP are potent agonists at both P2X3 and P2X2/3 receptors (11). Because α,β-meATP is a poor agonist for P2X2 receptors (1, 12), it was used to activate calcium flux in 1321N1 cells expressing human and rat homomeric P2X3 and heteromeric P2X2/3 receptors. A-317491 (S-enantiomer) was identified as a potent antagonist of α,β-meATP-activated recombinant rat and human P2X3 and P2X2/3 receptors and was significantly more potent than the R-enantiomer, A-317344 (Table 1). A-317491 showed significantly higher affinity in blocking P2X3 receptors (Table 1) compared with its ability to inhibit functional activation of other P2X receptors or the P2Y2 receptor (Table 2 and Fig. 1C).

Table 1.

In vitro activity of A-317491 and A-317344 at human and rat P2X3 and P2X2/3 receptors

| Calcium influx (Ki, nM) | A-317491 (S-enantiomer) | A-317344 (R-enantiomer) |

|---|---|---|

| Rat P2X3 | 22 ± 8 | >7,300 |

| Human P2X3 | 22 ± 3 | >10,000 |

| Rat P2X2/3 | 92 ± 11 | 1,300 ± 30 |

| Human P2X2/3 | 9 ± 2 | 1,100 ± 200 |

Ki calculated by the method of Cheng–Prusoff (19) using the IC50 values determined in the presence of 3 μM agonist (α,β-meATP); mean ± SEM (n = 3–10). pEC50 values for α,β-meATP at rat and human P2X3 receptors averaged 6.21 ± 0.05; pEC50 values at rat and human P2X2/3 receptors averaged 5.65 ± 0.08 (ref. 11 and unpublished observations).

Table 2.

Activity of A-317491 at other P2X and the P2Y2 receptors

| Agonist | Agonist conc., μM | Human P2X receptor | Agonist pEC50 | A-317491 pIC50 | A-317491 Ki, μM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATP | 0.2 | P2X1 | 7.73 ± 0.27 | 4.97 ± 0.17 | 2.53 |

| ATP | 5.0 | P2X2 | 6.11 ± 0.20 | 4.33 ± 0.13 | 4.13 |

| ATP | 4.0 | P2X4 | 6.30 ± 0.17 | <4 | >2.7 |

| BzATP | 10.0 | P2X7 | 5.86 ± 0.15 | <4 | >8.6 |

| UTP | 1.0 | P2Y2 | 7.99 ± 0.31 | <4 | >2.0 |

Data represent means ± SEM from at least three separate experiments.

Because the fast-desensitizing properties of the homomeric P2X3 receptors limit analysis of antagonist competitiveness (23), the nature of the antagonist actions of A-317491 was investigated by using P2X2/3 receptors. A-317491 was found to be a competitive antagonist of rat P2X2/3 receptors, with increasing concentrations of A-317491 producing rightward parallel shifts in the α,β-meATP dose–response curve (Fig. 1B). A Schild analysis (Fig. 1D) of these data yielded a pA2 value of 232 nM, which is in agreement with the estimated Ki value of 92 nM at rat P2X2/3 receptors (Table 1).

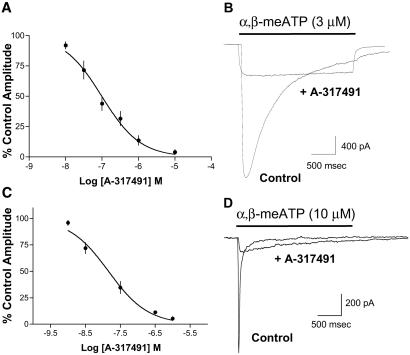

Fig. 2 summarizes electrophysiological studies of the effects of A-317491 on α,β-meATP-induced currents in both stably transfected cells and DRG neurons. Application of α,β-meATP evoked rapidly desensitizing currents in cells expressing human P2X3 receptors. A-317491 produced a concentration-dependent block of human P2X3 currents with an IC50 value of 97 nM (n = 3, Ki = 17 nM, Fig. 2 A and B). Similar results were obtained with recombinant human P2X3 receptors when ATP (3 μM) was used as the agonist (IC50 = 99 nM, n = 3, Ki = 4 nM) and with human P2X2/3 receptors when α,β−meATP (10 μM) was used as the agonist (IC50 = 169 nM, n = 2–6, Ki = 20 nM). A-317491 was equally effective at blocking rapidly desensitizing P2X3-mediated currents in rat DRG neurons (Fig. 2 C and D). A-317491 produced a concentration-dependent block of DRG currents with an IC50 value of 15 nM (n = 3). At all receptor subtypes, the effects of A-317491 were reversible, and essentially complete block of current was observed at a concentration of 10 μM. At this concentration, no nonspecific effects of the compound were observed on cellular input resistance or voltage-clamp holding current.

Fig 2.

(A) A-317491 concentration–response curve measured in stable cells expressing the recombinant human P2X3 receptor. Currents were activated by 3 μM α,β-meATP (control), and the percentage control response was measured in the presence of increasing concentrations of A-317491 (n = 3). (B) Representative α,β-meATP-induced current traces recorded from a P2X3-expressing cell before (control) and during application of 300 nM A-317491. (C) A-317491 concentration–response curve measured in rat DRG neurons. Currents were activated by 10 μM α,β-meATP, and the percentage control response was measured in the presence of increasing concentrations of A-317491 (n = 3). (D) Representative α,β-meATP-induced current traces recorded from a rat DRG neuron before (control) and during application of 300 nM A-317491.

A-317491 was also evaluated by Cerep for activity at 86 other receptors, enzymes, and ion channels (17). A-317491 was inactive (IC50 > 10 μM) at most of these other proteins. The only interaction with an IC50 < 10 μM was at the δ opioid receptor (IC50 ≈ 5 μM); in contrast, 10 μM A-317491 caused <10% inhibition of binding to the κ opioid receptor and only 15% inhibition of binding to the μ opioid receptor. Preliminary pharmacokinetic studies in rats indicated that 10 μmol/kg A-317491 had high (≈80%) systemic bioavailability after s.c. dosing (estimated plasma concentration = 15 μg/ml, >99% protein bound) and a half-life in plasma of 11 h. A-317491 did not undergo any detectable metabolism (oxidation or glucuronidation) in in vitro assays using human and rat liver microsomes (unpublished observations).

Antinociceptive Activity of A-317491.

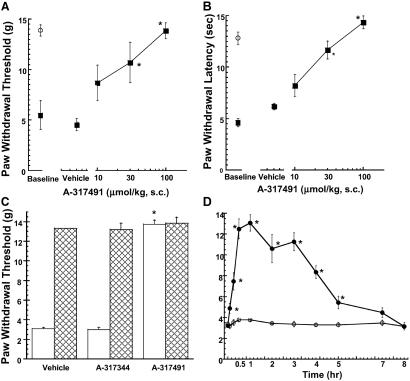

To further characterize the nociceptive role of P2X3 receptor activation, A-317491 was evaluated in a variety of animal pain models after s.c. administration. A-317491 was most potent in reducing mechanical allodynia and thermal hyperalgesia in the CCI model (ED50 = 10 and 15 μmol/kg s.c., Fig. 3 A and B) as compared with the other animal models of nociception tested (Table 3). A-317491 was fully effective in blocking nociception in this model, whereas the R-enantiomer, A-317344, was inactive (Fig. 3C). The antinociceptive effects of A-317491 in the CCI model were rapid in onset and persisted for 5 h after s.c. administration (Fig. 3D). In contrast to its full efficacy in the CCI model, A-317491 was only partially effective (50% reduction at 100 μmol/kg s.c.) in reducing tactile allodynia thresholds in the L5/L6 nerve ligation model (Table 3).

Fig 3.

A-317491 dose-dependently increases mechanical allodynia (von Frey hair) thresholds (A) and thermal paw withdrawal latencies (B) in the CCI model. ▪, Paw responses ipsilateral to the nerve injury; and ○, paw responses of the contralateral paw (mean ± SEM). (C) A-317491 (100 μmol/kg s.c.), but not A-317344 (100 μmol/kg s.c.) attenuates mechanical allodynia (open bars) in the CCI model of neuropathic pain. Hatched bars represent responses of the contralateral paw. (D) Time course for the onset and duration of A-317491 (100 μmol/kg s.c.)-mediated antinociception (•) in the CCI model. ○, Mechanical allodynia thresholds of CCI animals treated with vehicle. *, P < 0.05 as compared with vehicle-treated animals (n = 6 per group).

Table 3.

Analgesic profile of A-317491

| Model | ED50, μmol/kg s.c. | % Effect, 100 μmol/kg s.c. |

|---|---|---|

| Neuropathic pain | ||

| CCI | ||

| Mechanical | 15 | 100 ± 8 |

| Thermal | 10 | 110 ± 7 |

| L5/L6 nerve ligation | 100 | 50 ± 8 |

| Inflammatory pain | ||

| Formalin test (persistent phase) | 50 | 60 ± 3 |

| Chronic thermal hyperalgesia (CFA) | 30 | 74 ± 11 |

| Acute thermal hyperalgesia (Carrageenan) | >100 | 15 ± 5 |

| Visceral nociception | ||

| Mouse abdominal constriction | 27 | 78 ± 2 |

| Rat colonic distention | >100 | 0 |

| Rat visceral hyperalgesia | >100 | 0 |

| Postoperative somatic pain | >100 | 0 |

| Acute nociception | ||

| Rat acute thermal | >100 | 0 ± 10 |

| Rat acute mechanical | >100 | 0 ± 4 |

| Mouse hotplate | >100 | −10 ± 10 |

| Rat intraplantar capsaicin | >100 | 7 ± 5 |

| Formalin (acute phase) | >100 | 25 ± 7 |

Significantly different (P < 0.05) from vehicle-treated control animal responses (n = 6 per group).

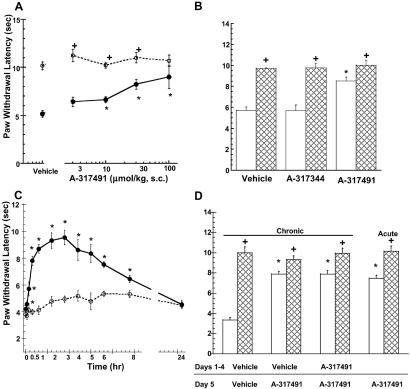

After 48 h of inflammation induced by the intraplantar administration of CFA, A-317491 fully blocked thermal hyperalgesia (Fig. 4A). The antinociceptive effects of A-317491 were specific to the injured paw, as the paw withdrawal latencies for the uninjured paw were not significantly altered by A-37491 at the doses tested. The antinociceptive effects of A-317491 in this model were also stereospecific because the R-enantiomer, A-317344, was inactive in this model (Fig. 4B). As was observed in the CCI model, the analgesic effects of A-317491 were rapid in onset and lasted for 8 h after s.c. administration (Fig. 4C). A-317491 produced an equivalent amount of antinociception after twice-daily administration for 4 days as was observed after acute administration (Fig. 4D).

Fig 4.

(A) A-317491 dose-dependently increases paw withdrawal latencies 48 h after intraplantar administration of CFA. •, Responses of CFA-injected paw. ○, Paw withdrawal latencies of uninjected contralateral paw (mean ± SEM). (B) A-317491 (100 μmol/kg s.c.), but not A-317344 (100 μmol/kg s.c.), attenuates CFA-induced thermal hyperalgesia (open bars) in the rat. Hatched bars represent responses of the contralateral paw. (C) Time course for the onset and duration of A-317491 (100 μmol/kg s.c.)-mediated antihyperalgesia (•) in the rat. ○, Paw withdrawal latencies of CFA-injected paws from animals treated with vehicle. (D) A-317491 was administered twice daily for 4 days. The antinociceptive effects of A-317491 (100 μmol/kg s.c., open bars) after repeated dosing in the CFA model were not significantly different as compared with vehicle-pretreated animals (chronic) or animals that received a single (acute) administration of A-317491. Hatched bars represent responses of the contralateral uninjected paw. *, P < 0.05 as compared with vehicle-treated animals (n = 6 per group). +, P < 0.05 as compared with CFA-treated paw.

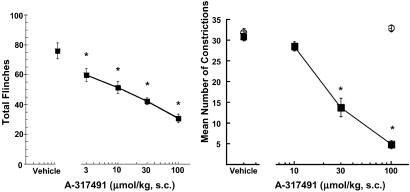

A-317491 also dose-dependently reduced nociceptive responses in chemically induced pain models including the persistent phase of the formalin test and a murine model of abdominal pain, the acetic acid-induced abdominal constriction assay (ACA) (Table 3; Fig. 5). The R-enantiomer, A-317344, was completely inactive in the ACA assay. As shown in Table 3, A-317491 was significantly more effective in reducing nociception in the persistent phase of the formalin assay compared with its activity in the acute phase immediately after formalin administration. A-317491 was also generally ineffective at doses up to 100 μmol/kg s.c. in reducing nociception elicited by a variety of other acute noxious stimuli including thermal, mechanical, capsaicin, and acute inflammatory hyperalgesia (Table 3).

Fig 5.

(Left) Antinociceptive effects of A-317491 in the persistent phase of the formalin test. (Right) A-317491 (▪), but not A-317344 (100 μmol/kg s.c., ○), dose-dependently reduces nociception in the mouse acetic acid-induced abdominal constriction assay. Data represent mean ± SEM. *, P < 0.05 as compared with vehicle-treated animals (n = 6 per group).

The effects of A-317491 were also evaluated in a model of postoperative pain induced by the incision of the skin, fascia, and plantaris muscle in the rat (22). In this model, A-317491 (100 μmol/kg s.c.) administered 30 min before or after the surgery, or locally (300 nmol) around the incision site 5 min before or after the surgery, did not decrease the mechanical allodynia observed 2 h after surgery (data not shown). In addition, these treatments did not modify the development of mechanical allodynia (von Frey hair sensitivity) 1 and 2 days after surgery (Table 3). A-317491 (100 μmol/kg s.c.) also had no effect on visceral pain in the rat as shown by its inability to attenuate either the visceromotor response observed after acute noxious colonic distension or inflammation-induced visceral hyperalgesia (Table 3).

Effects on Motor Activity, CNS, and Cardiovascular Function.

A-317491 had no significant effect (P > 0.05) on motor coordination at doses up to 300 μmol/kg s.c., as measured by the ability of rats to run on an accelerating rotating rod (rotorod assay, control latency = 59 ± 1 s, A-317491 300 μmol/kg latency = 53 ± 2 s). A-317491 also had no effect on spontaneous exploratory activity of rats in a novel open field at 100 μmol/kg s.c., but a statistically significant (32 ± 7%, P < 0.05) reduction of spontaneous exploratory activity was observed at 300 μmol/kg s.c. Rats were fully awake, were responsive to stimuli, and retained the righting reflex, consistent with their ability to perform the rotorod test at all doses tested.

A-317491 (10–300 μmol/kg s.c.) was also evaluated in a number of assays to assess general CNS function. No significant differences (P > 0.05) from vehicle-treated animals were noted for A-317491-treated mice in the Irwin test, the ethanol and barbital interaction assays, and the pentylenetetrazol-induced seizure assay (data not shown). Statistically significant, but dose-independent, anticonvulsant effects were found for A-317491 (100 μmol/kg s.c., 10% protection, P < 0.05) in the mouse electroconvulsive shock model, and a 0.4–0.6°C increase in rectal temperature was observed at 10 and 30 μmol/kg s.c. General CNS depression (respiration, sensory-motor deficits) and lethality were observed at a dose of 1,000 μmol/kg s.c. in mice. The cardiovascular effects of A-317491 were examined by using conscious, freely behaving rats instrumented with telemetry transmitters. After s.c. administration, A-317491 produced no statistically significant changes in mean arterial pressure or heart rate when administered to conscious rats at 300 μmol/kg.

Discussion

These data demonstrate that A-317491 is a potent and selective antagonist of P2X3 and P2X2/3 receptors. Like the nucleotide-based antagonist 2′,3′-O-2,4,6-trinitrophenyl (TNP)-ATP (22), A-317491 is a competitive antagonist of P2X2/3 receptors. However, unlike TNP-ATP, which also has high affinity for P2X1 receptors (24), A-317491 exhibits >100-fold selectivity for P2X3 and P2X2/3 receptors compared with its activity at other P2X receptor subtypes. A-317491 shows only very weak or no affinity for a large selection of other cell surface receptors, ion channels, and enzymes. A-317491, at concentrations up to 100 μM, also did not inhibit ectonucleotidase activity as measured by [32P]ATP degradation (unpublished observations). The specificity of the antagonist actions of A-317491 for P2X3 and P2X2/3 receptor blockade is further supported by the significantly weaker activity of the R-enantiomer, A-317344, as a P2X3 receptor antagonist. Electrophysiological data from both recombinant and native P2X3 receptor-mediated responses demonstrate that receptor block is rapid in onset, reversible, and devoid of nonspecific effects. A-317491 is also not susceptible to metabolic dephosphorylation like TNP-ATP (25). Thus, A-317491 represents the first non-nucleotide, potent and selective, antagonist of P2X3-containing channels.

A-317491 effectively reduced nociception in the CFA-induced model of chronic inflammatory pain and was particularly potent in reducing both thermal hyperalgesia and tactile allodynia in the CCI neuropathic pain model. The enhanced antinociceptive efficacy of A-317491 in the CCI model is consistent with the previously documented up-regulation of P2X3-containing channels in rat DRG and spinal dorsal horn in this model (13). Although less active, A-317491 also significantly reduced tactile allodynia thresholds in the L5/L6 nerve injury model. After L5/L6 nerve ligation, there is a significant decrease in the density of IB4-positive small diameter neurons in the L5/L6 DRG and a corresponding reduction in P2X3 immunoreactivity (26). However, a subpopulation of IB4 negative larger diameter neurons in the L5/L6 DRG remain intact, show P2X3 immunoreactivity, and demonstrate both fast (P2X3-like) and slowly (P2X2/3-like) desensitizing responses to ATP (26). Taken together, these data provide neurochemical and functional evidence that activation of P2X3 and P2X2/3 receptors is modulated during chronic pain and blockade of these receptors can reduce nociception mediated by both small and larger diameter sensory neurons in chronic pain states.

The antinociceptive effects of A-317491 in both the CFA and CCI models were rapid in onset and pharmacologically specific because similar antinociceptive effects were not observed after systemic administration of A-317344, the less active R-enantiomer. The antinociceptive effects of A-317491 in the CFA model were also maintained after repeated administration twice daily for 4 days. Thus, A-317491 shows reduced potential to produce tolerance compared with morphine, which has significantly reduced antinociceptive activity after repeated dosing (21). The antinociceptive effects of A-317491 were not accompanied by side effects commonly associated with other analgesic agents. A-317491 produced no significant effects on cardiovascular function and did not significantly alter motor performance at doses up to 100 μmol/kg s.c. in the rat. Additional studies in the mouse indicated that A-317491 was generally devoid of dose-dependent effects on CNS function up to doses of 300 μmol/kg s.c.

The antinociceptive effects of A-317491 in the CFA and CCI models are in agreement with other recent data demonstrating that intrathecal P2X3 antisense (27) and P2X3 receptor gene disruption (15, 16) reduce nociceptive sensitivity. Specifically, systemic administration of A-317491 was found to produce a similar reduction (≈50%) of spontaneous formalin-induced persistent nociception as was produced by P2X3 antisense or observed in P2X3 gene-disrupted animals. However, in contrast to the reported hyperalgesic effects of P2X3 receptor gene disruption (16), A-317491 produced significant antihyperalgesia in models of both chronic inflammatory hyperalgesia and neuropathic pain.

Unlike its analgesic effects in the chronic inflammatory and the neuropathic pain assays, A-317491 was ineffective in models of acute nociception involving a variety of noxious stimuli including heat, mechanical, and chemical (capsaicin, carrageenan, and formalin) stimulation. Although A-317491 was effective in reducing nociception in the acetic acid-induced mouse abdominal constriction assay, it was ineffective in reducing visceromotor responses after acute noxious colonic distension or inflammation-induced visceral hyperalgesia in the rat. A-317491 was also ineffective in reducing pain-related behaviors in a plantar incision model of postoperative somatic pain (22). In comparison to its analgesic efficacy in the CFA and neuropathic chronic pain models, these data suggest that activation of P2X3 and P2X2/3 receptors may be more involved in specific aspects of chronic inflammatory hyperalgesia and nerve injury-induced allodynia than in acute or visceral pain states.

Although the reasons for the differential analgesic efficacy of A-317491 in various pain states remain unclear, this pattern of activity may reflect different relative contributions of glutamatergic neurotransmission in various pain states. For example, recent studies have shown that the pharmacology of the plantar incision model of postoperative pain is different from the pharmacology of more classical models of inflammatory and neuropathic pain states (28). In particular, compounds that block spinal N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor and metabotropic glutamatergic receptor transmission have little antinociceptive effect in normal animals, but have antinociceptive properties in several models of chronic pain such as thermal hyperalgesia and mechanical allodynia observed in inflammatory (carrageenan, CFA) or neuropathic (sciatic nerve constriction, spinal nerve ligation) pain states (29, 30). Interestingly, it has recently been shown that spinal NMDA receptor and metabotropic glutamatergic receptor antagonists are ineffective at reducing incision-induced mechanical allodynia, suggesting a limited role of these receptors in this model of postoperative pain (28). Because previous data has shown that activation of P2X receptors facilitates the release of glutamate in spinal dorsal horn neurons (31), the analgesic effects of A-317491 may depend on glutamaterigically mediated nociceptive processes.

Previous pharmacological studies of the nociceptive role of P2X3-containing channels have been limited to the evaluation of low-affinity nonselective antagonists like suramin and pyridoxalphosphate-6-azophenyl-2′,4′-disulfonic acid (17) or more recently to the potent, but unstable antagonist, 2′,3′-O-2,4,6-trinitrophenyl-ATP, after local (32) or intrathecal administration (33, 34). In the absence of selective ligands, molecular approaches like gene disruption (15, 16) and gene knockdown (antisense) (27) studies have provided some evidence that P2X3-containing channels contribute to nociception. A-317491 represents an important advance in P2X3 receptor pharmacology because of its high degree of P2X receptor selectivity and its metabolic stability in vivo. Both the analgesic profile of A-317491 and the P2X3 gene disruption data (15, 16, 27) indicate that activation of P2X3-containing ion channels may contribute to the processes of peripheral and central sensitization states associated with some forms of chronic inflammatory pain and to nociceptive states arising from nerve injury.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Gerald F. Gebhart and Elizabeth Kamp (University of Iowa) for contributing visceral nociception data.

Abbreviations

CCI, chronic constriction injury

CFA, complete Freund's adjuvant

DRG, dorsal root ganglion

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

References

- 1.Chen C. C., Akopian, A. N., Sivilotti, L., Colquhoun, D., Burnstock, G. & Wood, J. N. (1995) Nature 377, 428-431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lewis C., Neidhart, S., Holy, C., North, R. A., Buell, G. & Surprenant, A. (1995) Nature 377, 432-435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vulchanova L., Riedl, M. S., Shuster, S. J., Buell, G., Suprenant, A., North, R. A. & Elde, R. (1997) Neuropharmacology 36, 1229-1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burnstock G. & Williams, M. (2000) J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 295, 862-869. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holton P. (1959) J. Physiol. (London) 145, 494-504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jahr C. E. & Jessell, T. M. (1983) Nature 304, 730-733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hamilton S. G., Warburton, J., Bhattacharjee, A., Ward, J. & McMahon, S. B. (2000) Brain 123, 1238-1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bleehen T. & Keele, C. A. (1977) Pain 3, 367-377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lynch K. J., Touma, E., Niforatos, W., Kage, K. L., Burgard, E. C., van Biesen, T., Kowaluk, E. A. & Jarvis, M. F. (1999) Mol. Pharmacol. 56, 1171-1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burgard E. C., Niforatos, W., van Biesen, T., Lynch, K. J., Touma, E., Metzger, R. E., Kowaluk, E. A. & Jarvis, M. F. (1999) J. Neurophysiol. 82, 1590-1598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bianchi B. R., Lynch, K. J., Touma, E., Niforatos, W., Burgard, E. C., Alexander, K. M., Park, H. S., Yu, H., Metzger, R., Kowaluk, E. A., et al. (1999) Eur. J. Pharmacol. 376, 127-138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Collo G., North, R. A., Kawashima, R., Merlo-Pich, E., Neidhart, S. & Surprenant, A. (1996) J. Neurosci. 16, 2495-2507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Novakovic S. D., Kassotakis, L. C., Oglesby, I. B., Smith, J. A., Eglen, R. M., Ford, A. P. & Hunter, J. C. (1999) Pain 80, 273-282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen Y., Shu, Y. & Zhao, Z. (1999) NeuroReport 10, 2779-2782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cockayne D. A., Hamilton, S. G., Zhu, Q.-M., Dunn, P. M., Zhong, Y., Novakovic, S., Malmberg, A. B., Cain, G., Berson, A., Kassotakis, L., et al. (2000) Nature 407, 1011-1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Souslova V., Cesare, P., Ding, Y., Akopian, A. N., Stanfa, L., Suzuki, R., Carpenter, K., Dickenson, A., Boyce, S., Hill, R., et al. (2000) Nature 407, 1015-1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jarvis M. F. & Kowaluk, E. A. (2001) Drug Dev. Res. 52, 220-231. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jacobson K. A., Jarvis, M. F. & Williams, M. (2002) J. Med. Chem. 45, 4057-4093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cheng Y. & Prusoff, W. H. (1973) Biochem. Pharmacol. 22, 3099-3108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jarvis M. F., Yu, H., Wismer, C., Mikusa, J., Zhu, C., Schweitzer, E., Alexander, K., Kohlhaas, K., Lynch, J. J., Lee, C.-H., et al. (2000) J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 295, 1156-1164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kowaluk E. A., Wismer, C., Mikusa, J., Zhu, C., Schweitzer, E., Lynch, J. J., Lee, C.-H., Jiang, M., Bhagwat, S. S., McKie, J., et al. (2000) J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 295, 1165-1174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brennan T. J., Vandermeulen, E. P. & Gebhart, G, F. (1996) Pain 64, 493-501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Burgard E. C., Niforatos, W., van Biesen, T., Lynch, K. J., Kage, K. L., Touma, E., Kowaluk, E. A. & Jarvis, M. F. (2000) Mol. Pharmacol. 58, 1502-1510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lewis C. J., Surprenant, A. & Evans, R. J. (1998) Br. J. Pharmacol. 124, 1463-1466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Virginio C., Robertson, G., Surprenant, A. & North, R. A. (1998) Mol. Pharmacol. 53, 969-973. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kage K., Niforatos, W., Zhu, C. Z., Lynch, K. J., Burgard, E. C., Honore, P. & Jarvis, M. F. (2002) Exp. Brain Res. 147, 511-519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Honore P., Kage, K., Mikusa, J., Watt, A., Johnston, J. F., Wyatt, J., Faltynek, C., Jarvis, M. F. & Lynch, K. (2002) Pain 99, 19-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zahn P. K. & Brennan, T. J. (1998) Anesthesia Analgesia 87, 1354-1359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Millan M. J. (1999) Prog. Neurobiol. 57, 1-164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dickenson A. H., Chapman, V. & Green, G. M. (1997) Gen. Pharmacol. 28, 633-638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gu J. G. & MacDermott, A. B. (1997) Nature 389, 749-753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jarvis M. F., Wismer, C. T., Schweitzer, E., Yu, H., van Biesen, T., Lynch, K. J., Burgard, E. C. & Kowaluk, E. A. (2001) Br. J. Pharmacol. 132, 259-269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tsuda M., Ueno, S. & Inoue, K. (19991) Br. J. Pharmacol. 127, 449-456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tsuda M., Koizumi, S., Kita, A., Shigemoto, Y., Ueno, S. & Inoue, K. (2000) J. Neurosci. 20, RC90., 1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.