Abstract

In situ analyses of single Listeria monocytogenes cells at subinhibitory concentrations of leucocin 4010 and nisin revealed two subpopulations when measured by fluorescence ratio imaging microscopy (FRIM) after staining with 5(6)-carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester. One subpopulation consisted of cells with a dissipated pH gradient (ΔpH), and the other consisted of cells that maintained ΔpH. The proportion of cells belonging to each subpopulation was estimated, and the concentrations of bacteriocins required to dissipate ΔpH for 90% of the cell population (ED90) was predicted. ED90 increased after the addition of sodium chloride (1 to 3% [wt/vol]) to the bacteriocin solutions, while ED90 decreased by the addition of sodium nitrite (60 and 100 ppm). Other meat additives, including sodium phosphate, sodium lactate, sodium citrate, and sodium acetate slightly increased ED90. The inhibitory effect of sodium chloride on the antilisterial activity of leucocin 4010 and nisin was confirmed on the surfaces of meat sausages. This study highlights the important practical implications of applying subinhibitory concentrations of bacteriocins, which results in unaffected target cells. In situ analyses by FRIM in combination with modeling of single-cell data can be applied to ensure that sufficient concentrations of bacteriocins are used in food preservation.

The tolerance of Listeria monocytogenes to refrigeration temperatures, high concentrations of NaCl, and anaerobic conditions (5, 14, 19) may necessitate the use of additional preservation for various food products such as vacuum-packed ready-to-eat meat products. The use of protective cultures, which produce bacteriocins or exert other kinds of competitive exclusion, may satisfy the demand for safe, fresh, and more natural meat products as proposed by many researchers (6, 11, 17).

Successful applications of bacteriocins and bacteriocin-producing strains have been demonstrated in various meat products (1, 11, 18, 31). However, in some cases survival of L. monocytogenes has been observed in foods after exposure to bacteriocins (1, 18, 31). Several studies have evaluated the activity of different bacteriocins, and they concluded that the bacteriocin concentration is critical to achieve sufficient inhibitory effect (1, 2, 24). An immediate reduction of L. monocytogenes that was inoculated onto vacuum-packaged meat sausages was only obtained when high concentrations of Leuconostoc carnosum 4010 (6.3 × 106 CFU/g) was applied (11). In addition to high bacteriocin concentrations, an even distribution of the bacteriocin-producing strain on a meat surface (27), and close contact between the protective culture and target organism have recently been identified as critical parameters for obtaining adequate competitive exclusion of L. monocytogenes (24). Survival of L. monocytogenes in meat products may also be prevented by additional use of various meat additives. Thus, to eliminate survivors and growth of L. monocytogenes in meat products, the combined effect of bacteriocins and additives still needs to be examined (24, 28, 33, 34).

Even though it has been emphasized that adequate concentrations of bacteriocins are important to obtain sufficient inhibition of L. monocytogenes, no detailed reports on the effect of bacteriocins at subinhibitory concentrations seem to be available. It is currently unknown whether treatment with subinhibitory concentrations of bacteriocin slightly affects the entire cell population or only attacks a fraction of the cell population, leaving another fraction of cells unaffected. Previously, we have performed in situ analyses of the interaction between bacteriocins and single cells of L. monocytogenes on a solid surface with the use of fluorescence ratio imaging microscopy (FRIM) (9). FRIM was used to determine the dissipation of the pH gradient (ΔpH) after exposure to nisin, and this setup revealed single cells of L. monocytogenes that maintained ΔpH depending on the history of the cells (9). Furthermore, the potential of this method to measure the interaction between bacteriocins and L. monocytogenes on the surfaces of food was highlighted (9).

The aim of the present study was to investigate the efficacy of leucocin 4010 or nisin at subinhibitory concentrations on single cells of L. monocytogenes. We applied the in situ technique FRIM on a solid surface to determine the heterogeneity with regard to pHi of cells within a population of L. monocytogenes. Furthermore, we examined the antilisterial activity of the bacteriocins in combination with various meat additives and verified these results directly on surfaces of meat sausages. Modeling of bimodal data was used to predict the concentration of bacteriocin needed to dissipate ΔpH for 90% of the cells when applied in combination with various meat additives.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals.

The chemicals used were of analytical grade and supplied by Merck (Darmstadt, Germany) unless otherwise stated.

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

Leuconostoc carnosum 4010 was isolated from vacuum-packed sliced ham as previously described (11) and is now commercially available as B-SF-43 from Chr. Hansen A/S, Hørsholm, Denmark. It was routinely grown for 48 h at 20°C in brain heart infusion (BHI; Difco, Detroit, Michigan) adjusted to pH 6.0 by using 1 M HCl. Listeria monocytogenes 4140 (isolated from bacon) was kindly provided by the Danish Meat Research Institute (Roskilde, Denmark). L. monocytogenes 4140 was routinely grown for 18 h at 37°C in BHI (pH 6.0). The strains were maintained in 20% (vol/vol) glycerol as frozen stock cultures at −80°C.

Bacteriocins.

Production of leucocin 4010 was carried out by using the method described by Budde et al. (11). Briefly described, Leuconostoc carnosum 4010 was grown in acetate-free MRS (26) containing 5% (wt/vol) glucose adjusted to pH 6.5 at 20°C for 48 h using agitation (50 rpm). Catalase (0.2 g/liter; Sigma, Montana) was added to the fermentate, and cells were removed by centrifugation at 16,300 × g for 10 min. Leucocin 4010 was partially purified by ammonium sulfate precipitation (40% [wt/vol]) and dialysis (Spectra/Por Dialysis Membrane; Spectrum Laboratories, Inc., California) with a 1-kDa cutoff. The partially purified leucocin 4010 was filter sterilized (0.20 μm; Minisart, Sartorius AG, Göttingen, Germany) and kept at −80°C until use. Bacteriocin activity, expressed in arbitrary units (AU) per milliliter, was determined by the microtiter assay system as described by Budde and Rasch (10) with L. monocytogenes 4140 as an indicator strain. Nisin (Applin & Barrett, Ltd., Danisco-Cultor, Beaminster, Dorset, England) was prepared as a stock solution in 0.05 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6.0) containing 10 mM glucose.

Fluorescence labeling of cells and immobilization.

Staining of L. monocytogenes 4140 with 5(6)-carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFDA-SE; Molecular Probes, Inc., Eugene, Oreg.) was carried out by using the method of Budde and Jakobsen (9). Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 10,400 × g for 5 min and resuspended in sterile-filtered (pore size, 0.22 μm; GP Express Membrane Filter; Millipore, Bedford, Mass.) phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.4) containing 0.15% (wt/vol) Na2HPO4, 0.022% (wt/vol) NaH2PO4, and 0.85% (wt/vol) NaCl. The fluorochrome, CFDA-SE, was added to obtain a final concentration of 10 μM, and the cell suspension was incubated at 37°C for 30 min. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 10,400 × g for 5 min and resuspended in 50 mM sterile-filtered potassium phosphate buffer (pH 6.0) supplemented with glucose (10 mM). The cell suspension was energized at 30°C for 30 min, harvested by centrifugation at 10,400 × g for 5 min, and resuspended in 50 mM sterile-filtered potassium phosphate buffer (pH 6.0) supplemented with glucose (10 mM). Stained cells were kept on ice until analysis and no longer than 2 h. Stained cells of L. monocytogenes 4140 were immobilized on a membrane filter (ME 25/31; Schleicher & Schuell, Dassel, Germany) by using the method described by Budde and Jakobsen (9) or on a slice of sausage before microscopic examinations.

FRIM.

FRIM measurements of L. monocytogenes 4140 were carried out using the setup described by Guldfeldt and Arneborg (21). This setup consisted of an inverted epifluorescence microscope (Axiovert 135 TV; Zeiss, Birkerød, Denmark) equipped with a Zeiss Fluar ×100 objective (numerical aperture, 1.3), a dichroic mirror (510 nm), and an emission band-pass filter (515 to 565 nm). Cells were excited at 490 and 435 nm with exposure times of 3 s by a monochromator equipped with a 75-W xenon lamp (Monochromator B; TILL Photonics GmbH, Planegg, Germany). To minimize photo bleaching of the stained cells, a 2.5% neutral-density filter was inserted between the optical fiber and the microscope. Fluorescence emission was collected with a cooled charge-coupled device camera (EEV 512 × 1024, 12-bit frame camera; Princeton Instruments) and images were analyzed by using the Metafluor 4.5 software (Universal Imaging Corp., West Chester, Pa.). Regions were defined around approximately 100 individual cells for each image by using Metafluor, and for each region ratio values (R490/435) were obtained by dividing the fluorescence intensity at 490 nm (pH sensitive wavelength) with the fluorescence intensity at 435 nm (a pH-insensitive wavelength).

Exposure of L. monocytogenes 4140 to leucocin 4010 and nisin in combination with meat additives.

Membrane filters or slices of sausages with the immobilized cells (ca. 106 and 107, respectively) were placed in a chamber containing a 300-μl solution of leucocin 4010 or nisin in combination with meat additives, including sodium chloride (1, 2, and 3% [wt/vol]), sodium nitrite (60 and 100 ppm), sodium citrate (0.2 and 0.4% [wt/vol]), sodium phosphate (0.155 and 0.31% [wt/vol]), sodium lactate (0.5 and 1.0% [wt/vol]), or sodium acetate (0.125 and 0.35% [wt/vol]). Experiments on membrane filters were carried out at pH 6.0. Sausages were prepared according to the method of Budde et al. (11) with the addition of selected meat additives including sodium chloride (2% [wt/vol]), sodium nitrite (60 ppm), sodium citrate (0.4% [wt/vol]), sodium lactate (1% [wt/vol]), or sodium acetate (0.25% [wt/vol]), and the pH of the sausages was ca. 6.3. For each combination of bacteriocin and meat additive, microscopic images were acquired in triplicates on each sample with duplicate experiments. Images were acquired within 5 min after exposure of the cells to the bacteriocin solutions.

Determination of the number of viable cells of L. monocytogenes after exposure to bacteriocins.

To determine the number of viable L. monocytogenes cells after exposure to bacteriocins for 5 min, the membrane filters were aseptically removed from the microscope chamber and transferred to 10 ml of peptone saline solution. The membrane filters were thoroughly vortexed, and tenfold dilutions made in peptone saline solution were plated on BHI agar (Oxoid, Ltd., Basingstoke, United Kingdom). CFU were enumerated after incubation for 48 h at 37°C.

Statistical methods.

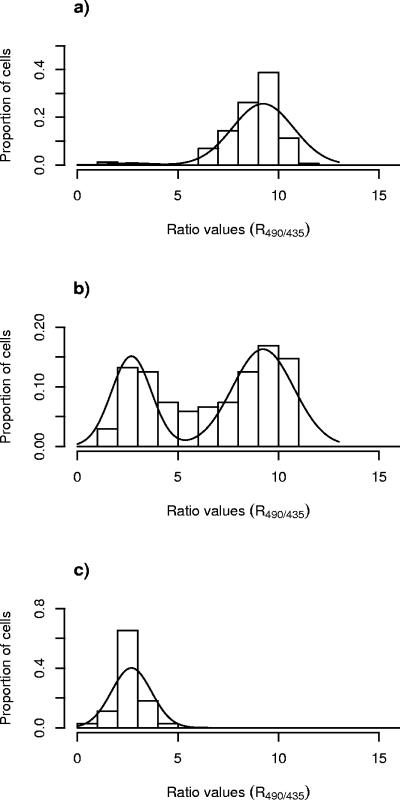

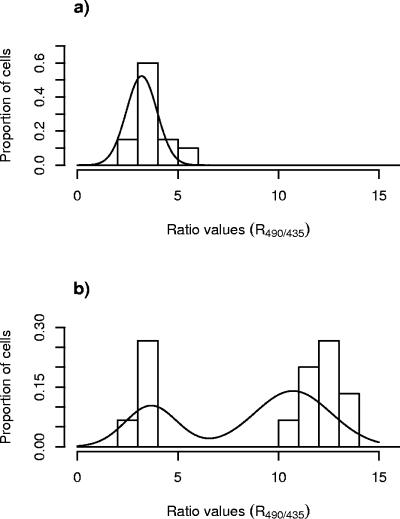

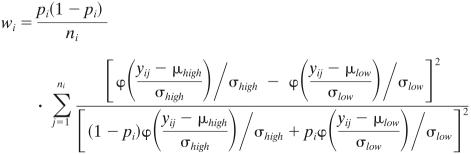

A novel statistical method was developed to describe the dissipation of ΔpH for single cells of L. monocytogenes exposed to the bacteriocins. Statistical analyses were carried out by using R490/435 values. In all experiments, single-cell analysis of R490/435 values revealed a bimodal distribution (i.e., two subpopulations) as outlined in Fig. 2: one subpopulation showed an average R490/435 of ca. 2.5 (subpopulation 1), and the other subpopulation showed an average R490/435 of ca. 9 (subpopulation 2). For each of the different combinations of bacteriocin and meat additive, the following order of procedures was used (each step of the statistical procedure is explained in details in the Appendix). For step 1, the proportion of cells belonging to each subpopulation was estimated by fitting a normal mixture model to the ratio values of individual cells for each image. For step 2, the relation between bacteriocin concentration and the proportion of cells in each subpopulation was estimated by weighted logistic regression. For step 3, predictions of the concentration of bacteriocin corresponding to 90% of the cells belonging to subpopulation 1 (ED90 value), as well as the approximate standard errors, were made.

FIG. 2.

Distributions of R490/435 values of single cells of L. monocytogenes 4140 cells immobilized on a filter membrane and measured by FRIM upon exposure to leucocin 4010 at concentrations of 0 (a), 9,600 (b), and 24,000 (c) AU/ml.

RESULTS

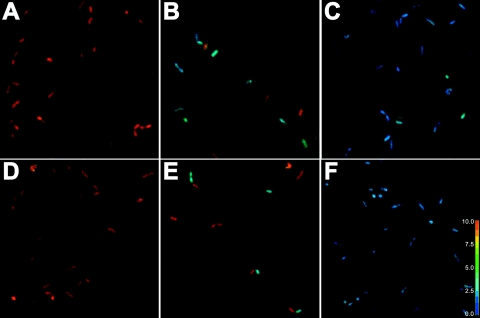

Ratio images of L. monocytogenes upon exposure to various concentrations of leucocins 4010 or nisin are seen in Fig. 1. In Fig. 1A and D, ratio images for cells not being exposed to bacteriocins are shown, and the R490/435 of L. monocytogenes was approximately 9. This value corresponded to pHi 7.9 according to Budde and Jakobsen (9), and at the extracellular pH (pHex) of 6.0, cells maintained a ΔpH of approximately 2 pH units. Ratio images of cells exposed to high concentrations of leucocins (24,000 AU/ml) and nisin (1800 IU/ml) are shown in Fig. 1C and F, and the R490/435 of cells was approximately 2.5, corresponding to pHi 6.0 according to Budde and Jakobsen (9). At subinhibitory concentrations of leucocin 4010 (9,600 AU/ml) and nisin (400 IU/ml), ΔpH dissipated in a fraction of the cells, while the remaining part of the cells maintained their ΔpH within the time of exposure (5 min) which is also reflected in Fig. 1B and E. The viable count of L. monocytogenes 4140 decreased from 5.5 × 105 to 2.3 × 105 CFU/ml after treatment with 9,600 AU of leucocin 4010/ml and from 2.5 × 105 to 6 × 104 CFU/ml after treatment with 400 IU of nisin/ml. Exposure to higher concentrations of leucocin (24,000 AU/ml) and nisin (1,800 IU/ml) caused ΔpH dissipation in all L. monocytogenes cells examined as seen in Fig. 1C and F. However, the viable count only decreased from 5.5 × 105 to 2.3 × 105 CFU/ml after exposure to 24,000 AU of leucocin 4010/ml, whereas the viable count decreased from 2.5 × 105 to 1.4 × 102 CFU/ml after exposure to 1,800 IU of nisin/ml.

FIG. 1.

Ratio images of L. monocytogenes 4140 cells immobilized on a filter membrane at an extracellular pH of 6.0 and exposed to leucocin at concentrations of 0 (A), 9,600 (B), and 24,000 (C) AU/ml or nisin at concentrations of 0 (D), 400 (E), and 1,800 (F) IU/ml. A color-coded R490/435 scale is shown on the right.

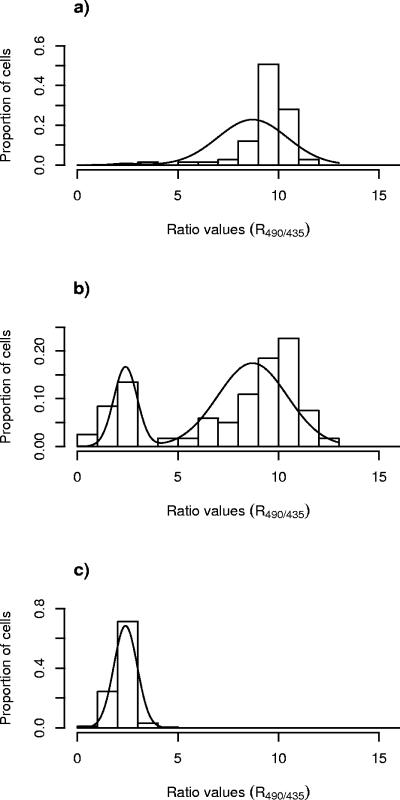

More detailed information on the distributions of the measured R490/435 values shown as bars, as well as the fitted curves of the binomial distributions of the R490/435 values (estimated according to steps i and ii of the statistical procedure), are shown in Fig. 2 and 3 for L. monocytogenes exposed to leucocin 4010 and nisin, respectively. In the absence of bacteriocins, all L. monocytogenes cells were designated as subpopulation 2, showing R490/435 values with an average of ca. 9.0 (Fig. 2a and 3a). Exposure of L. monocytogenes to subinhibitory concentrations of leucocin 4010 (9,600 AU/ml) or nisin (400 IU/ml) revealed two subpopulations (Fig. 2b and 3b). One subpopulation showed low values of R490/435, with an average of ca. 2.5, and these cells were designated as subpopulation 1, and the other cells with high values of R490/435 (average of ca. 9.0) were designated as subpopulation 2 (Fig. 2b and 3b). However, the histograms in Fig. 2b and 3b also show that a minor fraction of cells exhibited R490/435 values in between the typical low value (μlow) and the typical high value (μhigh) calculated as explained in step i of the statistical procedure. These cells were assigned to subpopulation 1 or 2 according to the weighting scheme described in step ii of the statistical analysis. After exposure to sufficiently high concentrations of leucocin 4010 (24,000 AU/ml) and nisin (1,800 IU/ml), all L. monocytogenes cells examined were designated as subpopulation 1 (Fig. 2c and 3c).

FIG. 3.

Distributions of R490/435 values of single cells of L. monocytogenes 4140 cells immobilized on a filter membrane and measured by FRIM upon exposure to nisin at concentrations of 0 (a), 400 (b), and 1,800 (c) IU/ml.

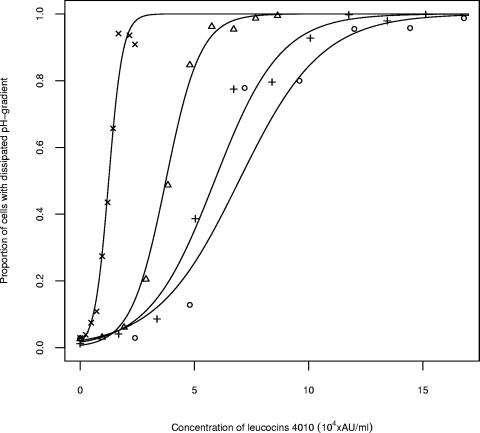

Within the time of exposure, meat additives alone did not affect the number of cells designated to subpopulation 2 but slightly changed the value of μhigh for this subpopulation (results not shown). Upon exposure to leucocin 4010 in combination with sodium chloride, the percentages of cells designated to the two subpopulations were estimated by using weighted logistic regression. Addition of sodium chloride decreased the antilisterial effect of leucocin 4010, and it was necessary to increase the concentrations of leucocin 4010 to obtain the same effect as without sodium chloride (Fig. 4). The concentration of bacteriocins required to dissipate ΔpH for 90% of the cells (ED90) in the absence or in the presence of the various meat additives was predicted for each of the conditions (Table 1). ED90 increased from 1.9 × 104 to 1.1 × 106 AU/ml for leucocin 4010 when 3% (wt/vol) sodium chloride was added (Table 1). Sodium chloride also inhibited the activity of nisin, and ED90 increased from 4.1 × 102 to 1.1 × 104 IU/ml upon addition of 3% (wt/vol) sodium chloride (Table 1). Addition of either sodium phosphate (0.155 and 0.31% [wt/vol]), sodium lactate (0.125 and 0.25% [wt/vol]), sodium citrate (0.4% [wt/vol]), or sodium acetate (0.25% [wt/vol]) slightly decreased the antilisterial effect (Table 1). The addition of sodium nitrite (60 and 100 ppm) slightly enhanced the antilisterial effect in combination with either leucocin 4010 or nisin (Table 1). The addition of sodium nitrite (100 ppm) decreased the ED90 from 1.9 × 104 AU/ml to 1.7 × 104 AU/ml for leucocin 4010, whereas ED90 decreased from 420 to 310 IU/ml for nisin (Table 1).

FIG. 4.

Proportion of L. monocytogenes 4140 cells assigned to subpopulation 1, with low R490/435 values corresponding to cells with dissipated ΔpH after exposure to various concentrations of leucocin 4010 in combination with sodium chloride at percent (wt/vol) concentrations of 0 (×), 1 (▵), 2 (+), and 3 (○).

TABLE 1.

ED90 values for L. monocytogenes 4140 upon exposure to leucocin 4010 or nisin and different meat additives

| Meat additive (% [wt/vol])a | ED90b (SD)

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Leucocin 4010 (AU/ml, 104) | Nisin (IU/ml, 102) | |

| No additive | 1.9 (0.6) | 4.2 (0.2) |

| Sodium chloride | ||

| 1.0 | 54.1* (1.1) | 38* (1.1) |

| 2.0 | 90.5* (2.6) | 71.2* (2.1) |

| 3.0 | 109.4* (4.1) | 108.3* (4.6) |

| Sodium phosphate | ||

| 0.155 | 2.7* (0.8) | 5.6* (0.2) |

| 0.31 | 3.7* (0.7) | 8.5* (0.3) |

| Sodium acetate | ||

| 0.125 | 2.0 (0.7) | 5.2* (0.2) |

| 0.25 | 2.3* (0.9) | 6.8* (0.2) |

| Sodium lactate | ||

| 0.5 | 2.2* (0.5) | 6.1* (0.2) |

| 1.0 | 2.8* (1.0) | 8.2* (0.4) |

| Sodium citrate | ||

| 0.2 | 2.6* (0.5) | 4.2 (0.2) |

| 0.4 | 3.1* (0.6) | 5.1* (0.2) |

| Sodium nitrite | ||

| 60 ppm | 1.6† (0.8) | 3.4† (0.1) |

| 100 ppm | 1.7† (0.7) | 3.1† (0.1) |

Values are percentages except as noted.

The value is an estimated average. *, the ED90 value is significantly (P < 0.05) higher than the ED90 value observed in the absence of meat additives; †, the ED90 values is significantly (P < 0.05) lower than the ED90 value observed in the absence of meat additives.

The combined antilisterial effect of the bacteriocins and meat additives was verified by in situ measurements on the surface of meat sausages. A significant antilisterial effect of leucocin 4010 (48,000 AU/ml) was observed on surfaces of meat sausages without sodium chloride added, and ΔpH was dissipated for all cells (Fig. 5a). In contrast, when sodium chloride was added (2.5% [wt/vol]) to the meat sausage, the antilisterial effect of leucocin 4010 (48,000 AU/ml) decreased and at the end of the exposure time (5 min) less than half of the cells were designated to subpopulation 1, leaving more than half of the cells unaffected (Fig. 5b). Similar reductions in the antilisterial effect of nisin on meat surfaces were observed when sodium chloride was added to the meat matrix (results not shown). The smaller impact of the other meat additives on the antilisterial effect that was observed in the liquid system (Table 1) could not be verified when the additives were mixed into the meat matrix (results not shown).

FIG. 5.

Distributions of R490/435 values of single cells of L. monocytogenes 4140 cells immobilized on slices of sausages containing no sodium chloride (a) or 2.5% (wt/vol) sodium chloride (b) after exposure to leucocin 4010 at a concentration of 48,000 AU/ml.

DISCUSSION

Based on the two subpopulations behavior of L. monocytogenes observed in this study, it is likely that treatment of L. monocytogenes in meat products at subinhibitory concentrations of bacteriocins will result in the inactivation of a fraction of the population rather than weakening each individual cell of the population. This emphasizes the importance of using sufficient concentrations of bacteriocin in food products in order to eliminate survival and growth of surviving L. monocytogenes.

Bacteriocin molecules tend to aggregate and form large complexes due to their hydrophobic nature (7, 40). These properties potentially lead to localized gradients of bacteriocin molecules, which may be particularly critical at limited concentrations of bacteriocin. The presence of localized gradients is the most reasonable explanation for the two subpopulations observed in the current study. Bimodal distributions may be even more pronounced in solid foods such as meat products containing bacteriocin-producing strains, since the transmission of bacteriocins happens through diffusion and not convection (30)

The occurrence of phenotypic heterogeneity of L. monocytogenes cannot be excluded as an explanation for the two subpopulations observed upon exposure to subinhibitory concentrations of bacteriocins. Phenotypic heterogeneity constitutes the nongenetic variation existing among individual cells within an isogenic population and is related to different levels of basal gene expression rather than different gene possession (39). Phenotypic heterogeneity arises via progression through the cell cycle (15) and is typically seen when cells are exposed to stressful conditions such as heat (3). Phenotypic heterogeneity has also been observed for Escherichia coli cells surviving and being persistent to antibiotic treatment (4). Furthermore, the heterogeneity of cells grown on solid substrates has been observed with respect to bacteriocin sensitivity, RNA content, and levels of carotenoid pigmentation (9, 13).

The bimodal distribution does probably not reflect genotypic heterogeneity within the L. monocytogenes population resulting in different susceptibilities of single cells to the bacteriocins. The frequency of genotypic heterogeneity of L. monocytogenes 412 (identical to strain 4140) concerning resistance to nisin and pediocin PA-1 has been thoroughly investigated and shown to be 10−4 and 10−6, respectively (20). This low rate of bacteriocin resistance combined with the fact that ΔpH was dissipated for all single cells at high concentration of bacteriocin makes bacteriocin resistance an unlikely explanation to the bimodal distribution. Likewise, bacteriocin resistance did not seem to be the primary reason for L. monocytogenes surviving on sausages after exposure to leucocin 4010, since no resistant strains could be retrieved among the survivors (27). To confirm the suggested origin of the two subpopulations at subinhibitory concentrations of bacteriocin, detailed investigations of cells from each subpopulation should be performed in the future with the use of either fluorescence-activated cell sorting or micromanipulation.

Traditionally, the growth-inhibitory effect caused by bacteriocins added to foods has been determined by plate counting. Using this method, L. monocytogenes is transferred to optimal growth conditions, e.g., with regard to media not containing bacteriocin and to optimal temperature for growth. In the present study, exposure of L. monocytogenes to nisin resulted in a pronounced increase in the number of cells with dissipated ΔpH (subpopulation 1), which corresponded to a decrease in the viable count on BHI agar. However, exposure to leucocin 4010 at concentrations that dissipated ΔpH for all cells only resulted in ca. 50% reduction in the viable count, which may be explained by recovery of L. monocytogenes upon transfer to BHI agar. The existence of such a recovery mechanism was supported by the observation of very different colony sizes, including pinpoint colonies of L. monocytogenes after exposure to leucocin 4010 (results not shown). A repair mechanism was also demonstrated in Lactobacillus spp. after bacteriocin treatment, when viable counts were compared to direct observation of pore formation by flow cytometry (10). Similar recovery was not observed on a meat sausage (11, 27), which may be related to the concurrent presence of leucocin 4010 and Listeria monocytogenes and potentially the combined effect of a hostile sausage environment. These observations highlight the importance of in situ investigations of bacteriocins and their target organisms, as demonstrated in the present study. Previously, FRIM has been used to measure pHi in L. monocytogenes (9, 37), Bacillus licheniformis (23), Candida krusei, and Saccharomyces cerevisiae (22), as well as lactic acid bacteria (38), on solid surfaces such as membrane filters or poly-l-lysine-coated glass slides. In the present study, FRIM was successfully applied for measuring pHi directly on the surface of meat sausages, and in the future these in situ measurements may advantageously be performed on other food surfaces.

Within the short time of exposure (5 min), meat additives alone showed no effect on the proportion of L. monocytogenes cells designated to the two subpopulations (results not shown). Sodium chloride inhibited the activity of leucocin 4010 and nisin demonstrating that a higher amount of bacteriocin was required to inactivate all L. monocytogenes cells on meat sausages containing 3% (wt/vol) NaCl compared to products containing lower concentrations of NaCl. The inhibitory effect of NaCl on leucocin 4010 and nisin is in accordance with the inhibitory effect of NaCl on the antilisterial effect of pediocin, and this inhibition was negated by increasing the concentration of bacteriocin (8). Similar effects of sodium chloride was observed on the growth-inhibitory effect of Leuconostoc carnosum 4010 (24), sakacin K (25), lactocin (41), and nisin and pediocin (16, 28). Decreased activities of various bacteriocins in the presence of sodium chloride have been explained by chloride anions inhibiting the binding of bacteriocin to the cell surface of a target organism (8), sodium chloride inducing conformational changes of bacteriocins (29), or changing the envelope of the target organism (28).

A decrease in the activities of leucocin 4010 and nisin was observed in the presence of sodium phosphate, sodium acetate, sodium lactate, and sodium citrate (Table 1). Previously, the addition of phosphate at concentrations of 40 mmol/liter or higher was shown to inhibit the effect of nisin, and this effect was ascribed to the ability of the phosphate ions to block the electrostatic interaction between bacteriocin and cell membrane (8). It is not known whether the decrease in bacteriocin activities when applied in mixtures with the above-mentioned meat additives could be explained by a similar ion-blocking effect. In contrast, previous work has demonstrated a synergistic growth-inhibitory effect of sodium lactate (1.8 to 3.6% [wt/vol]) and nisin (4,000 to 6,000 IU/ml) against L. monocytogenes (33) and a synergistic growth-inhibitory effect of sodium lactate (2% [wt/vol]) or sodium citrate (1.5% [wt/vol]) in combination with nisin (500 IU/ml) against Arcobacter butzleri (35). The different results may be explained by the different times of exposure to bacteriocins and meat additives for the target organism since only the initial activity of bacteriocins was determined by FRIM and not a possible long-term effect of the meat additives on the bacteriocin activity. Increased antilisterial activity was also demonstrated for Leuconostoc carnosum 4010 immobilized in a structured gelatin system after addition of sodium nitrite (60 or 100 ppm) (24). In contrast, sodium nitrite decreased the growth-inhibitory effect of lactocin 705 against L. monocytogenes (41).

In conclusion, we show here that the use of subinhibitory concentrations of leucocin 4010 and nisin resulted in two subpopulations of L. monocytogenes where only one subpopulation was affected by the treatment rather than weakening each individual cell of the population. The apparent recovery of L. monocytogenes cells when removed from leucocin 4010 to optimal growth conditions on BHI agar plates for estimation of viable counts emphasizes the importance of using in situ measurements to examine the effect of bacteriocins. In situ measurements of the activity of leucocin 4010 or nisin in combination with various meat additives were successfully performed on surfaces of meat sausages. Sodium chloride decreased the activity of leucocin 4010 and nisin when applied in a solution, as well as in a meat matrix. The effectiveness of bacteriocins should carefully be evaluated in food products containing the desired levels of additives since these may affect the concentrations of bacteriocins needed to produce safe food products.

Acknowledgments

This study was financially supported by the Danish FØTEK 2 program (grant 93 s-2469-å95-00064) and the Danish Bacon and Meat Council.

We thank Joss-Delves-Broughton (Applin & Barrett, Ltd., Danisco-Cultor, Beaminster, Dorset, England) for providing the purified nisin and Ann-Britt Frøstrup (The Danish Meat Research Institute, Roskilde, Denmark) for preparation of the sausages.

Appendix

Step 1.

The distribution of R490/435 values in an image Yij was described by a bimodal distribution with a mode (“top”) around the typical values μ and the dispersion σ of R490/435 values for cells belonging to subpopulation 1 and 2, respectively: Yij ≈ N(μlow, σlow2), if cell j in image i had a low R490/435 value (subpopulation 1); and Yij ≈ N(μhigh, σhigh2), if cell j in image i had a high R490/435 value (subpopulation 2)

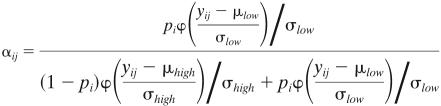

The (unobserved) status of each individual cell was modeled by binomial distributions bin(1, pi) with the underlying proportion pi depending on the image. The unknown true pi was the key figure that expressed the proportion of cells in subpopulation 1. The model is a well-defined statistical model, known as a normal mixture model, in which estimates of the unknown model parameters could be found by a maximum-likelihood estimation, often carried out by the EM algorithm (32). For a single image this could be accomplished by commercial statistical software with standard clustering routines, but for several images simultaneously it was not possible and the applied algorithm is given explicitly in the following:

(i) Starting values for pi, μlow, σlow, μhigh, and σhigh were chosen.

(ii) E-step. The probability of belonging to subpopulation 1 αij was calculated for each cell.  where ϕ was the standard normal density function.

where ϕ was the standard normal density function.

(iii) M-step. The proportion of cells belonging to subpopulation 1 was estimated by calculating the average of the individual cell probabilities.

|

(2) |

Estimates of the two intensity value distributions were calculated by using the individual cell probabilities as weights as follows:

|

(3) |

|

(iv) Iteration was carried out between steps ii and iii until convergence was obtained.

Step 2.

Using a standard logistic regression procedure, the SAS Genmod Procedure (36), the relation between the pi values deduced from step 1 and the corresponding bacteriocin concentration Ci was modeled by a logistic curve:

|

(4) |

This analysis required binomial data for each observation i, i.e., a number of “observed successes” and the number of total possible successes, in this case, the expected number of cells belonging to subpopulation 1 corresponding to nipi out of ni possible. Weights, wi, which were used to determine the probability of a cell to belong to each of the subpopulations, were calculated according to the weighting scheme given by:  This choice of weights ensured that the uncertainty of the proportions pi in the analysis equaled that given by using standard asymptotic statistics theory on the normal mixture model.

This choice of weights ensured that the uncertainty of the proportions pi in the analysis equaled that given by using standard asymptotic statistics theory on the normal mixture model.

Approximate variances of the R490/435 values in subpopulations 1 and 2 could be deduced by differentiating the log-likelihood function twice. In this case, the log-likelihood function differentiated twice with respect to pi resulted in:

|

(6) |

To account for variations in the pi values that were likely to occur due to sampling, replication, and lack of logistic curve fit, the weighted logistic regression was carried out with a so-called overdispersion factor. The deviance scale option of the procedure was chosen (36).

Step 3.

The concentration level corresponding to 90% cells belonging to subpopulation 1 with low R490/435 ED90 values was derived from the logistic relation:

|

(7) |

Since this was a function of the two logistic curve parameters, the approximate uncertainty of the ED90, SEED90, was deduced by standard error analysis (12), giving:

|

(8) |

where  and

and  were the estimation variances of α and β and sαβ was the estimation covariance, and all three values could be seen from standard logistic regression software output. Comparison of ED90 values for two different compounds was based on the uncertainty of a difference in ED90 values:

were the estimation variances of α and β and sαβ was the estimation covariance, and all three values could be seen from standard logistic regression software output. Comparison of ED90 values for two different compounds was based on the uncertainty of a difference in ED90 values:

|

(9) |

REFERENCES

- 1.Aasen, I. M., S. Markussen, T. Møretrø, T. Katla, L. Axelsson, and K. Naterstad. 2003. Interactions of the bacteriocins sakacin P and nisin with food constituents. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 87:35-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abriouel, H., M. Maqueda, A. Gálvez, M. Martínez-Bueno, and E. Valdivia. Inhibition of bacterial growth, enterotoxin production, and spore outgrowth in strains of Bacillus cereus by bacteriocin AS-48. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:1473-1477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Attfield, P. V., H. Y. Choi, D. A. Veal, and P. J. L. Bell. 2001. Heterogeneity of stress gene expression and stress resistance among individual cells of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Microbiol. 40:1000-1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balaban, N. Q., J. Merrin, R. Chait, L. Kowalik, and S. Leibler. 2004. Bacterial persistence as a phenotypic switch. Science 305:1622-1625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barakat, R. K., and L. J. Harris. 1999. Growth of Listeria monocytogenes and Yersinia enterocolitica on cooked modified-atmosphere-packaged poultry in the presence and absence of a naturally occurring microbiota. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:342-345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benkerroum, N., A. Daoudi, and M. Kamal. 2003. Behaviour of Listeria monocytogenes in raw sausages (merguez) in presence of a bacteriocin-producing lactococcal strain as a protective culture. Meat Sci. 63:479-484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bhunia, A. K., M. C. Johnson, and B. Ray. 1988. Purification, characterization, and antimicrobial spectrum of a bacteriocin produced by Pediococcus acidilactici. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 65:261-268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bhunia, A. K., M. C. Johnson, B. Ray, and N. Kalchayanand. 1991. Mode of action of pediocin AcH from Pediococcus acidilactici H on sensitive bacterial strains. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 70:25-33. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Budde, B. B., and M. Jakobsen. 2000. Real-time measurements of the interaction between single cells of Listeria monocytogenes and nisin on a solid surface. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:3586-3591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Budde, B., and M. Rasch. 2001. A comparative study on the use of flow cytometry and colony forming units for assessment of the antibacterial affect of bacteriocins. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 63:65-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Budde, B., T. Hornbæk, T. Jacobsen, V. Barkholt, and A. G. Koch. 2003. Leuconostoc carnosum 4010 has the potential for the use as a protective culture for vacuum-packed meats: culture isolation, bacteriocin identification, and meat application experiments. Int. J. Food. Microbiol. 83:171-184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cameron, J. M. 1982. Error analysis, p. 515-545. In S. Kotz and N. L. Johnson (ed.), Encyclopedia of statistical science, vol. 2. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York, N.Y. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Choo-Smith, L.-P., K. Maquelin, T. van Vreeswijk, H. A. Bruning, G. J. Puppels, N. A. Ngo Thi, C. Kirschner, D. Naumann, D. Ami, A. M. Villa, F. Orsini, S. M. Doglia, H. Lamfarraj, G. D. Sockalingum, M. Manfait, P. Allouch, and H. P. Endtz. 2001. Investigating microbial (micro)colony heterogeneity by vibrational spectroscopy. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:1461-1469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cole, M. B., M. V. Jones, and C. Holyoak. 1990. The effect of pH, salt concentration and temperature on the survival and growth of Listeria monocytogenes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:63-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davey, H. M., and D. B. Kell. 1996. Flow cytometry and cell sorting of heterogeneous microbial populations: the importance of single-cell analysis. Microbiol. Rev. 60:641-696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.De Martinis, E. C. P., and B. D. G. M. Franco. 1998. Inhibition of Listeria monocytogenes in a pork product by a Lactobacillus sake strain. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 42:119-126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Martinis, E. C. P., and F. Z. Freitag. 2003. Screening of lactic acid bacteria from Brazilian meats for bacteriocin formation. Food Control 14:197-200. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dicks, L. M. T., F. D. Mellett, and L. C. Hoffman. 2004. Use of bacteriocin-producing starter cultures of Lactobacillus plantarum and Lactobacillus curvatus in production of ostrich meat salami. Meat Sci. 66:703-708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grau, F. H., and P. B. Vanderlinde. 1992. Occurrence, numbers, and growth of Listeria monocytogenes on some vacuum-packaged processed meats. J. Food Prot. 55:4-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gravesen, A., A.-M. Jydegaard Axelsen, J. Mendes de Silva, T. B. Hansen, and S. Knøchel. 2002. Frequency of bacteriocin resistance development and associated fitness costs in Listeria monocytogenes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:756-764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guldfeldt, L. U., and N. Arneborg. 1998. Measurement of the effects of acetic acid and extracellular pH on intracellular pH of nonfermenting, individual Saccharomyces cerevisiae cells by fluorescence microscopy. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:530-534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Halm, M., T. Hornbæk, N. Arneborg, S. Sefa-Dedeh, and L. Jespersen. 2004. Lactic acid tolerance determined by measurement of intracellular pH of single cells of Candida krusei and Saccharomyces cerevisiae isolated from fermented maize dough. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 94:97-103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hornbæk, T., J. Dynesen, and M. Jakobsen. 2002. Use of fluorescence ratio imaging microscopy and flow cytometry for estimation of cell vitality for Bacillus licheniformis. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 215:261-265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hornbæk, T., T. F. Brocklehurst, and B. B. Budde. 2004. The antilisterial effect of Leuconostoc carnosum 4010 in the presence of sodium chloride and sodium nitrite examined in a structured gelatin system. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 92:129-140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hugas, M., M. Garriga, M. Pascual, M. T. Aymerich, and J. M. Monfort. 2002. Enhancement of sakacin K activity against Listeria monocytogenes in fermented sausages with pepper or manganese as ingredients. Food Microbiol. 19:519-528. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jack, R. W., J. Wan, J. Gordon, K. Harmark, B. E. Davidson, A. J. Hillier, R. E. Wettenhall, M. W. Hickey, and M. J. Coventry. 1996. Characterization of the chemical and antimicrobial properties of piscicolin 126, a bacteriocin produced by Carnobacterium piscicola JG126. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62:2897-2903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jacobsen, T., B. B. Budde, and A. G. Koch. 2003. Application of Leuconostoc carnosum for biopreservation of cooked meat products. J. Appl. Microbiol. 94:1-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jydegaard, A.-M., A. Gravesen, and S. Knøchel. 2000. Growth condition-related response of Listeria monocytogenes 412 to bacteriocin inactivation. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 31:68-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee, S., T. Iwata, and H. Oyagi. 1993. Effects of salts on conformational change of basic amphipathic peptides from β-structure to α-helix in the presence of phospholipid liposomes and their channel-forming ability. Biochem. Biophys. Acta 1151:75-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Malakar, P. K., T. F. Brocklehurst, A. R. Mackie, P. D. G. Wilson, M. H. Zwietering, and K. van't Riet. 2000. Microgradients in bacterial colonies: use of fluorescence ratio imaging, a non-invasive technique. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 56:71-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mattila, K., P. Saris, and S. Työppönen. 2003. Survival of Listeria monocytogenes on sliced cooked sausage after treatment with pediocin AcH. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 89:281-286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McLachlan, G. J., and T. Krishnan. 1997. The EM-algorithm and extensions, p. 68-71. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York, N.Y.

- 33.Nykänen, A., K. Weckman, and A. Lapveteläinen. 2000. Synergistic inhibition of Listeria monocytogenes on cold-smoked rainbow trout by nisin and sodium lactate. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 61:63-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Parente, E., M. A. Giglio, A. Ricciardi, and C. Francesca. 1998. The combined effect of nisin, leucocin F10, pH, NaCl and EDTA on the survival of Listeria monocytogenes in broth. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 40:65-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Philips, C. A. 1999. The effect of citric acid, lactic acid, sodium citrate, and sodium lactate, alone and in combination with nisin, on the growth of Arcobacter butzleri. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 29:424-428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.SAS Institute, Inc. 1999. SAS/STAT® user's guide, version 8, p. 1363-1464. SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, N.C.

- 37.Shabala, L., B. Budde, T. Ross, H. Siegumfeldt, and T. McMeekin. 2002. Responses of Listeria monocytogenes to acid stress and glucose availability monitored by measurements of intracellular pH and viable counts. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 75:89-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Siegumfeldt, H., K. B. Rechinger, and M. Jakobsen. 2000. Dynamic changes of intracellular pH in individual lactic acid bacterium cells in response to a rapid drop in extracellular pH. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:2330-2335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sumner, E. R., and S. V. Avery. 2002. Phenotypic heterogeneity: differential stress resistance among individual cells of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiology 148:345-351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.van Laack, R. L. J. M., U. Schillinger, and W. H. Holzapfel. 1992. Characterization and partial purification of a bacteriocin produced by Leuconostoc carnosum LA44A. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 16:183-195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vignolo, G., S. Fadda, M. N. de Kairuz, A. P. de, R. Holgado, and G. Oliver. 1998. Effects of curing additives on the control of Listeria monocytogenes by lactocin 705 in meat slurry. Food Microbiol. 15:259-264. [Google Scholar]